Synopsis

The cytochrome P450 (CYP) drug metabolizing enzymes are essential for the efficient elimination of many clinically used drugs. These enzymes typically display high interindividual variability in expression and function resulting from enzyme induction, inhibition, and genetic polymorphism thereby predisposing patients to adverse drug reactions or therapeutic failure. There are also substantial species differences in CYP substrate specificity and expression that complicate direct extrapolation of information from humans to veterinary species. This article reviews the available published data regarding the presence and impact of genetic polymorphisms on CYP-dependent drug metabolism in dogs in the context of known human-dog CYP differences. Canine CYP1A2, which metabolizes phenacetin, caffeine, and theophylline, is the most widely studied polymorphic canine CYP. A single nucleotide polymorphism resulting in a CYP1A2 premature stop codon (c.1117C>T; R383X) with a complete lack of enzyme is highly prevalent in certain dog breeds including Beagle and Irish wolfhound. This polymorphism was shown to substantially affect the pharmacokinetics of several experimental compounds in Beagles during preclinical drug development. However, the impact on the pharmacokinetics of phenacetin (a substrate specific for human CYP1A2) was quite modest probably because other canine CYPs are capable of metabolizing phenacetin. Other canine CYPs with known genetic polymorphisms include CYP2C41 (gene deletion), as well as CYP2D15, CYP2E1, and CYP3A12 (coding SNPs). However the impact of these variants on drug metabolism in vitro or on drug pharmacokinetics is unknown. Future systematic investigations are needed to comprehensively identify CYP genetic polymorphisms that are predictive of drug effects in canine patients.

Keywords: Dog, Canine, Genetic polymorphism, Cytochrome P450, Pharmacokinetics

INTRODUCTION

The cytochrome P450 (CYP) drug metabolizing enzymes are critical to the efficient elimination of many drugs used in clinical practice. Unfortunately in humans, and probably in all species of veterinary importance, there is considerable inter-individual variability in the activity of these enzymes 1. Consequently, for a given drug dosage the effect can range from undetectable or suboptimal (with high enzyme activity, high drug clearance, and low plasma levels) to excessive or toxic (with low enzyme activity, low drug clearance, and high plasma levels). Causes of this variability can include concurrent exposure to CYP enzyme inhibitors and/or inducers in the diet or from coadministered medications (previously reviewed in 2). Genetic variation is also a well-established cause of CYP activity variability in humans, and current evidence suggests that it may be equally important in veterinary species, including dogs 1. Consequently, clinical assays for CYP gene variants that significantly impact drug disposition could be a useful tool to enable rational drug selection and dosage for the individual patient. This chapter reviews the current state of knowledge regarding the dog CYPs focusing on potentially clinically important genetic variants that could influence drug efficacy and toxicity.

DOG-HUMAN CYP SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES

Much of the available published data on the CYPs so far concern the human CYPs. Indeed, the United States FDA requires detailed label information regarding the involvement of specific human CYPs in the metabolism of all newly approved drugs intended for use in humans. Although much of the information can be applied in a general fashion to the dog CYPs, it is becoming increasingly apparent that there are important differences in the metabolism of drugs by human and dog CYPs, much of which have yet to be determined. Specific examples of some of the known similarities and differences are as follows.

CYP substrate specificity

Table 1 lists common CYP drug substrates in humans compared with dogs. The CYPs are named according to gene sequence similarity and grouped according to family (number), subfamily (letter) and unique gene product (number), as in the canine CYP2B11 gene (family - 2, subfamily - B, 11th gene identified). Because of significant species differences in gene sequence of these enzymes, each species tends to have their unique CYP names, although orthologs (genes derived from the same ancestral gene that diverged following speciation) are found in most species. For example CYP2B11 is considered to be the canine ortholog of human CYP2B6 3, 4. Orthologs also tend to have roughly similar substrate specificities. For example both human CYP2B6 and canine CYP2B11 metabolize propofol 4, 5. However significant species differences exist. For example midazolam is metabolized exclusively by human CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 (but not by human CYP2B6) while dog CYP2B11 (and not CYP3A12) primarily metabolizes midazolam 6. Similarly, both dog CYP1A2 and dog CYP2A13 metabolize phenacetin 7, 8, while only human CYP1A2 (and not human CYP2A6) metabolizes this drug. Although most dog CYPs have unique names, 3 of the drug metabolizing CYPs (CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP2E1) have identical names to those found in other mammalian species, in part because they have relatively conserved gene sequences between species, and in part because their naming preceded the convention to give unique names to the drug metabolizing CYPs in different species.

Table 1.

| Human CYP | Substrates | Dog CYP | Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A2 | Caffeine Phenacetin Tacrine Theophylline |

CYP1A2 | Caffeine Phenacetin Theophylline |

| CYP2A6 | Nicotine | CYP2A13 | Phenacetin |

| CYP2B6 | Bupropion Efavirenz Propofol |

CYP2B11 | Atipamezole Diclofenac Ketamine Medetomidine Midazolam Propofol Temazepam |

| CYP2C8 | Amodiaquine | CYP2C21/CYP2C41 | Diclofenac |

| CYP2C9 | Diclofenac Tolbutamide S-warfarin |

||

| CYP2C19 | Omeprazole S-mephenytoin |

||

| CYP2D6 | Bufuralol Codeine Debrisoquine Dextromethorphan |

CYP2D15 | Celecoxib Debrisoquine (poor) Desipramine Dextromethorphan Imipramine |

| CYP2E1 | Chlorzoxazone | CYP2E1 | Chlorzoxazone |

| CYP3A4 | Midazolam Triazolam Terfenadine Nifedipine |

CYP3A12 | Diazepam Diclofenac Eplerenone Imatinib Midazolam |

Data from P450 Drug Interaction Table. Indiana University Department of Medicine, 2009. Available at: http://medicine.iupui.edu/clinpharm/ddis/table.aspx. Accessed April 20, 2013.

Data from Martinez MN, Antonovic L, Court M, et al. Challenges in exploring the cytochrome P450 system as a source of variation in canine drug pharmacokinetics. L Drug Metab Rev 2013;45(2):218–30.

Both sources also list other dog and human CYP substrates, inhibitors, and inducers.

CYP abundance

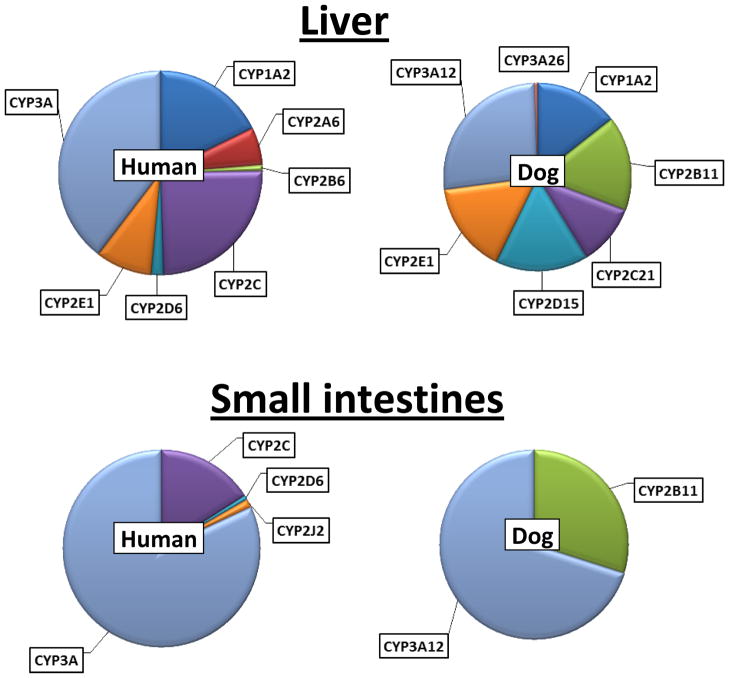

Apart from differences in catalytic properties between dog and human CYPs, these enzymes also differ in the relative amount of each family and subfamily between dogs and humans. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the different CYPs in liver and small intestinal mucosa of human 9, 10 and dog 11. The liver has the highest content of drug metabolizing CYPs and is the most important organ for CYP mediated drug elimination. The small intestine also has a high specific content of certain CYPs located within the mucosa and serves to decrease absorption of intact (unmetabolized) drugs thereby limit systemic availability of orally administered drugs. Similarities between dog and human are apparent in that the CYP3A subfamily enzymes are the predominant isoforms in liver and intestines of both species. On the other hand, the CYP2D subfamily enzyme CYP2D15 is more highly expressed (as a percentage of total CYPs) in the livers of dogs versus CYP2D6 in humans. Furthermore, the CYP2B subfamily enzyme CYP2B11 is more highly expressed in both livers and intestines of dogs, than CYP2B6 in human livers and intestines. This difference could be a consequence of the many genetic mutations that have been associated with both the CYP2D6 and CYP2B6 genes in humans. A clinical consequence is that drugs metabolized by CYP2D15 and/or CYP2B11 may have lower systemic levels in dogs than in humans.

Figure 1.

Comparison of relative CYP isoform protein levels in dog and human liver and small intestines. Protein amounts were determined by quantitative immunoblotting for human liver (Shimada et al, 1994) and intestines (Paine et al, 2006) or by quantitative mass spectrometry for Beagle dog tissues (Heikkinen et al, 2012). Note that CYP2A forms were not assayed in dog tissues and CYPs other than CYP2B11 and CYP3A12 were below the detection level in dog intestines.

CANINE CYPS WITH KNOWN GENETIC POLYMORPHISM

Table 2 summarizes published data regarding known genetic polymorphisms in the canine drug metabolizing CYP enzymes including variant description, allele frequencies, and effects of the variant on enzyme function in vitro and in vivo.

Table 2.

Summary of known canine CYP genetic polymorphisms

| Enzyme | Genetic variant | Variant allele frequency | In vitro effect | In vivo effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A2 | SNP c.1117C>T causing premature stop codon mutation at amino acid position 373 (R373X) | 6% in 99 mixed breed dogs from Brazil; 38% in 214 Beagles from Japan; see Figure 3 for complete numbers. | No functional enzyme | ~50% lower phenacetin clearance after oral administration; no difference in phenacetin clearance after IV administration |

| CYP2C41 | Partial or complete gene deletion | Gene absent in 24 of 28 (86%) dogs (Beagles and mixed breed) | No functional enzyme | Unknown |

| CYP2D15 | S186G, I250F, I307V (WT2) | Unknown | Lower bufuralol hydroxylation than V1,*2 and *3; dextromethorphan demethylation and celecoxib hydroxylation same as for V1,*2 and *3 | Unknown |

| S186G, I250F, I307V, I338V, K407E (V1) | Unknown | No effect | Unknown | |

| S186G (CYP2D15*2) | Unknown | No effect | Unknown | |

| I250F, I307V (CYP2D15*3) | Unknown | No effect | Unknown | |

| CYP2E1 | Y485D | 15% in 100 mixed breed dogs; 19% in 13 Beagles | No effect | Unknown |

| CYP3A12 | T309S, R421K, K422E, N423K, M452T | Unknown | No effect | Unknown |

CYP1A2 premature stop codon (CYP1A2stop) polymorphism

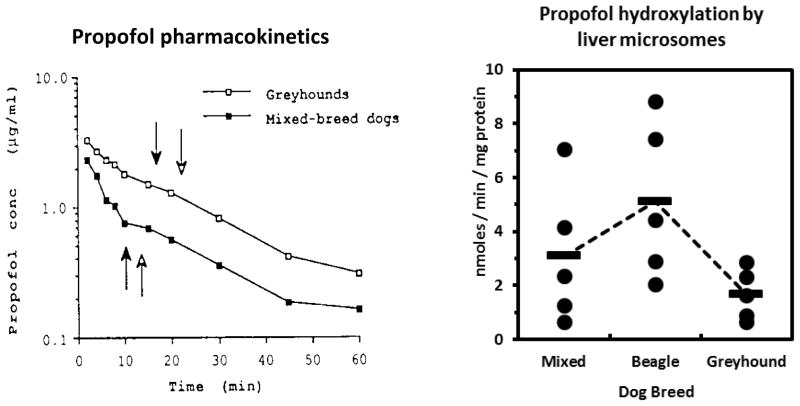

The most comprehensively studied canine CYP genetic polymorphism is the premature stop codon mutation (c.1117C>T; R373X) located in the coding region of the CYP1A2 gene that results in complete loss of hepatic CYP1A2 protein and associated enzyme activity 12, 13. This mutation was discovered independently by two Japanese pharmaceutical companies during preclinical testing of two unrelated investigational compounds (YM-64227 12 and AC3933 13) that showed highly polymorphic pharmacokinetics of these compounds in their Beagle dog colonies. Both groups used genetic testing to screen a relatively large number of their Beagle dog colonies and found that from 11 to 17% of their dogs had the homozygous mutant genotype and consequently did not express functional CYP1A2 12, 13. The effect on the plasma drug levels of the investigational drugs was large with up to 17 times increased levels in deficient dogs (see Figure 2) 20, 21. However animals that had at least one normal CYP1A2 copy (heterozygotes) did not have substantially different drug levels from the wild-type dogs. Several other investigational compounds including GTS-21 22 and BTP-2 23 have also been associated with variable CYP1A2 metabolism in Beagles.

Figure 2.

Effect of the CYP1A2 premature stop codon mutation (R373X) on the pharmacokinetics of the investigational compound YM-64227 (left) and the analgesic drug phenacetin (right) after oral administration to genotyped Beagle dogs. Data for YM-64227 are from Tenmizu et al (2006) and for phenacetin are from Whiterock et al (2012). The effect of the CYP1A2 premature stop codon on YM-64227 (about 25 times greater mean plasma AUC) was much greater than on phenacetin (about 2 times greater AUC).

As yet the effect of this polymorphism on the pharmacokinetics and effects of clinically used drugs is unclear. In vitro studies 8 using liver microsomes from CYP1A2 deficient and expressing dogs indicated that phenacetin and tacrine (both selectively metabolized by human CYP1A2) were more slowly metabolized in deficient livers. However, other (human selective) CYP1A2 substrates including caffeine and melatonin were unaffected by the deficiency, implying that dog CYP1A2 does not selectively metabolize these latter drugs (unlike human CYP1A2). A recent study of phenacetin pharmacokinetics following oral and intravenous administration to CYP1A2 genotype Beagles 15 showed about 2-fold higher phenacetin exposure (based on area under the plasma concentration time curve; AUC) after oral administration in CYP1A2 deficient dogs, but there were much smaller (non-significant) differences in phenacetin levels after intravenous exposure. The authors concluded that phenacetin was not a selective or robust in vivo probe for CYP1A2 probably because of metabolism of phenacetin by other enzymes (such as canine CYP1A1 and/or canine CYP2A13). These findings indicate that the effect of CYP1A2stop on a particular drug will depend on the degree of importance of canine CYP1A2 in clearance and cannot be extrapolated directly from human data.

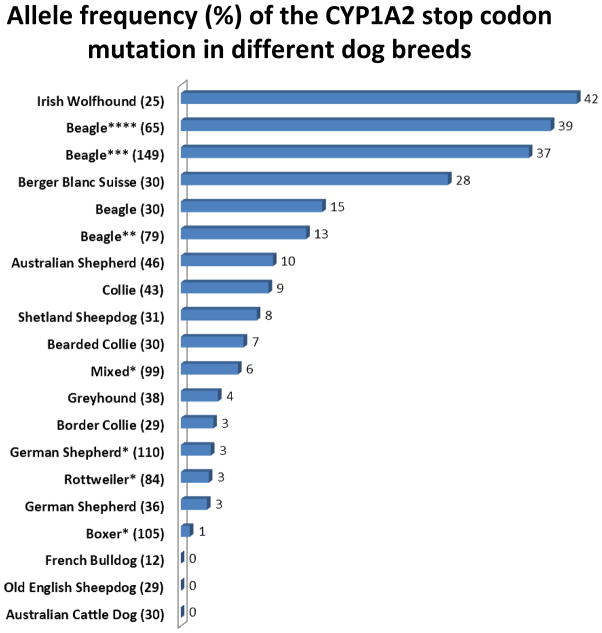

The prevalence of CYP1A2stop appears to vary considerably both between and within dog breeds. Apart from research colony Beagle dogs in Japan 12, 13, several other studies have surveyed this mutation in nearly 40 different dog breeds (and mixed breed dogs) from the USA 24, Germany 25, and Brazil 14 (see Figure 3). The Irish Wolfhound had the highest allele frequency (42%) followed by the Japanese Beagles (37–39%) and Berger Blanc Suisse (28%). Interestingly the beagles studied in Germany 25 and the USA 24 had less than half the allele frequency (15% and 13%, respectively) than the beagles from Japan 12, 13 possibly reflecting colony founder effect differences. The remaining breeds studied had allele frequencies of 10% or less indicating that the likely frequency of the enzyme deficient homozygous variant dogs would be 1% or less in the population (i.e. relatively rare). Interestingly many of the remaining affected breeds were herding dogs including Australian Shepherd, Collie, Shetland Sheepdog, Bearded Collie, Border Collie, and Old English Sheepdog 25. Although this could be sampling bias, it might also indicate a common (although perhaps more recent) ancestry of CYP1A2stop with the MDR1 gene deletion (MDR1del) mutation, which is commonly found in herding breed dogs 26. The latter results in drug sensitivity from deficiency of the P-glycoprotein transporter encoded by MDR1 (see Chapter7). Regardless, the clinical consequence is that herding breed dogs could be affected by multiple genetic defects (MDR1del and CYP1A2stop) influencing drug disposition and response.

Figure 3.

Allele frequency (number of variant alleles as percent of total alleles) of the CYP1A2 stop codon mutation (R373X) in different dog breeds. Shown after each breed are the numbers of individual dogs that were sampled. Data are from dogs located in Brazil (*Scherr et al, 2011), USA (**Whiterock et al, 2007), Japan (***Mise et al, 2004 and ****Tenmisu et al, 2004), and Germany (Aretz and Geyer 2011). Only data from breeds in which DNA from at least 10 different dogs in that breed were sampled are shown. Other breeds in which at least one dog had the deficient allele included Whippet, Deerhound, Dalmation, and Jack Russell Terrier (Aretz and Geyer 2011).

CYP2C41 gene deletion

During initial attempts to clone canine CYP2C21 from dog liver RNA, a second CYP2C subfamily enzyme named CYP2C41 was discovered 16. This latter isoform was found to be present at both the RNA and genomic DNA level in only about 16% (4 of 25) of dogs (2 of 10 mixed breeds and 2 of 18 Beagles). This contrasted with CYP2C21 that was found to be expressed in all dogs examined. This finding suggests the presence of a partial or complete deletion of the CYP2C41 gene in many dogs. This was confirmed (albeit with a lower deletion frequency) by a study in another laboratory that showed detectable CYP2C41 mRNA in 6 of 11 Beagle dogs 27. In vitro studies of recombinant canine CYPs indicate that CYP2C41 metabolizes many of the same substrates as CYP2C21 (including diclofenac and S-mephenytoin) although with much less efficiency 28, 29. Consequently, the impact of the CYP2C41 deletion on canine drug metabolism or pharmacokinetics may be somewhat limited.

CYP2D15 amino acid variants

Several studies have identified different CYP2D15 mRNA forms expressed in liver that vary in predicted amino acid coding sequence at 3 to 5 different residues (Table 2). Although it is presumed that these changes are the result of SNPs, this has not yet been established such as through genotyping of multiple dogs. In vitro studies of expressed amino acid variants suggest that the impact of these coding changes on enzyme function may be somewhat limited. The only exception was the WT2 form, identified by Roussel et al (1998) that showed about 50% lower bufuralol hydroxylation compared with the other forms but unchanged celecoxib hydroxylation 18 or dextromethorphan demethylation 17. As yet the impact of these genetic variants on drug pharmacokinetics or effect has not been reported.

Paulson et al (1999) originally undertook their study of CYP2D15 variants in order to explain polymorphic celecoxib clearance in vivo and celecoxib hydroxylation in vitro in a research colony of Beagle dogs. However they did not directly address this hypothesis such as through CYP2D15 genotyping of phenotyped dogs. Furthermore, although CYP2D15 was shown to be capable of hydroxylating celecoxib, a significant role for other CYPs was not excluded. Consequently, the mechanism underlying the celecoxib pharmacokinetic polymorphism remains unexplained.

CYP2E1 amino acid variant

A SNP (1453T>C) resulting in a tyrosine for histidine substitution at amino acid position 485 (H485Y) was discovered during initial cloning of the CYP2E1 cDNA from canine liver RNA 19. Survey genotyping found an allele frequency of 15% in 100 mixed breed dogs, and 19% in 13 Beagles. An in vitro study comparing expressed wild-type (485H) and variant (485Y) CYP2E1 isoforms showed no difference in chlorzoxazone hydroxylation activity. However, since only one substrate was evaluated, substrate-dependent effects cannot be excluded. In vivo effects of this SNP on drug pharmacokinetics have not been reported.

CYP3A12 amino acid variants

A variant (called CYP3A12*2) that included 5 different nucleotide differences from the initial cloned sequence, and predicted to cause 5 unique amino acid changes was also discovered during cloning of the CYP3A12 cDNA from canine liver RNA 18. In vitro experiments showed no effect of these amino acid changes on testosterone 6-β-hydroxylation by recombinant enzymes. Genotype frequencies or any association of genotype with drug metabolism phenotype measured in vivo have not been reported.

OTHER DOG CYPS ASSOCIATED WITH PHENOTYPIC VARIABILITY

CYP2B11 and breed related anesthetic drug hypersensitivity

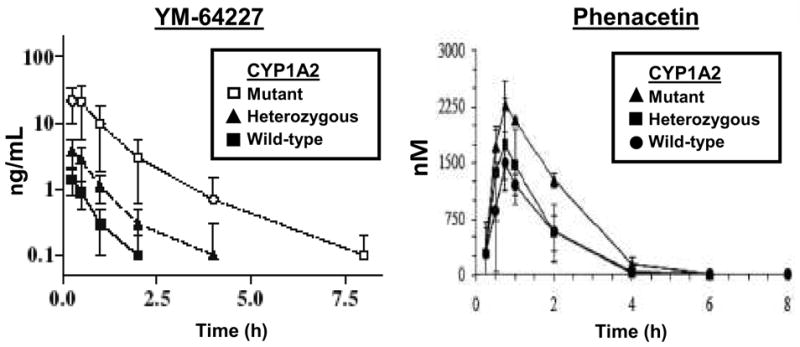

Severely delayed recovery have been reported for certain dog breeds (primarily Greyhounds and possibly other sighthounds) following use of the injectable anesthetic agents, including thiopental and thiamylal 30–33. Although initially attributed to decreased drug redistribution from the central compartment resulting from reduced body fat in Greyhounds, a series of studies demonstrated that the effect could be attributed to decreased drug clearance in Greyhounds compared with mixed breed dogs, and was also prevented by pretreatment with a microsomal enzyme inducer (phenobarbital) 30, 31. A subsequent study showed that propofol (another short acting anesthetic) was also cleared more slowly in Greyhounds 34, and pretreatment with chloramphenicol, a CYP inhibitor, decreased drug clearance even further 35. In vitro mechanistic studies identified CYP2B11 as being the main enzyme responsible for CYP-dependent clearance of propofol 4, 36. As yet, the molecular genetic basis for this breed-dependent difference in drug metabolism has not been reported.

CONCLUSIONS

Published evidence indicates that variability in drug metabolism by CYP in dogs is likely to be considerable and is explained in part by the presence of genetic polymorphisms that vary between dog breeds. However to date, few CYPs (mainly CYP1A2) have been systematically investigated, and the influence of the discovered genetic variants on the pharmacokinetics of clinically used drugs and their effects is unclear. Predictions of genetic effects on particular drugs (such as the effect of CYP1A2 stop codon mutation on phenacetin pharmacokinetics) from human data are complicated by human-dog differences in CYP substrate specificity and abundance. Consequently clinical studies confirming the impact of discovered variants on drug response in canine patients will be essential.

Figure 4.

Greyhounds show slower clearance (left) and lower liver metabolism (right) of propofol compared with mixed breed and Beagle dogs. The left panel (from (Zoran et al. 1993)) shows mean propofol concentrations in 10 Greyhounds and 10 mixed breed dogs given propofol intravenously at a dose of 5 mg / kg body weight. The arrows indicate time of return of the righting reflex (filled arrow) and ability to stand (open arrow). The right panel shows propofol hydroxylation rates measured by HPLC with in vitro incubations of liver microsomes prepared from male Greyhounds, beagles and mixed breed dogs (5 each). The points represent data from individual dog livers, while the horizontal lines indicate the mean values of each group. Adapted from Court MH, Hay-Kraus BL, Hill DW, et al. Propofol hydroxylation by dog liver microsomes: assay development and dog breed differences. Drug MetabDispos 1999;27(11):1293.

Key points.

Polymorphisms in genes encoding CYP enzymes could explain adverse drug effects or therapeutic failure in canine patients.

A premature stop codon mutation in CYP1A2 is commonly found in certain dog breeds, including Beagle and Irish wolfhound.

Although the CYP1A2 premature stop codon has shown large effects on the pharmacokinetics of some experimental compounds, effects on commonly used clinical drugs is currently unknown.

Polymorphisms also exist in genes encoding canine CYP2C41, CYP2E1, CYP2D15, and CYP3A12 that have the potential to impact the metabolism of a large number of different drugs.

Anesthetic drug hypersensitivity in Greyhounds may be the result of a genetic variant affecting canine CYP2B11 expression or function.

Footnotes

Disclosures: This work was supported by funds provided by the William R. Jones Endowed Chair in Veterinary Medicine at Washington State University. There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mosher CM, Court MH. Comparative and veterinary pharmacogenomics. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2010;199(199):49. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-10324-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trepanier LA. Cytochrome P450 and its role in veterinary drug interactions. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2006;36(5):975–985. v. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baratta MT, Zaya MJ, White JA, et al. Canine CYP2B11 metabolizes and is inhibited by anesthetic agents often co-administered in dogs. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2010;33(1):50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2885.2009.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hay Kraus BL, Greenblatt DJ, Venkatakrishnan K, et al. Evidence for propofol hydroxylation by cytochrome P4502B11 in canine liver microsomes: breed and gender differences. Xenobiotica. 2000;30(6):575. doi: 10.1080/004982500406417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Court MH, Duan SX, Hesse LM, et al. Cytochrome P-450 2B6 is responsible for interindividual variability of propofol hydroxylation by human liver microsomes. Anesthesiology. 2001;94(1):110. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200101000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mills BM, Zaya MJ, Walters RR, et al. Current cytochrome P450 phenotyping methods applied to metabolic drug-drug interaction prediction in dogs. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38(3):396. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.030429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou D, Linnenbach AJ, Liu R, et al. Expression and characterization of dog cytochrome P450 2A13 and 2A25 in baculovirus-infected insect cells. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38(7):1015–1018. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.033068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mise M, Hashizume T, Komuro S. Characterization of substrate specificity of dog CYP1A2 using CYP1A2-deficient and wild-type dog liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36(9):1903–1908. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.022301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paine MF, Hart HL, Ludington SS, et al. The human intestinal cytochrome P450 “pie”. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34(5):880. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.008672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimada T, Yamazaki H, Mimura M, et al. Interindividual variations in human liver cytochrome P-450 enzymes involved in the oxidation of drugs, carcinogens and toxic chemicals: studies with liver microsomes of 30 Japanese and 30 Caucasians. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270(1):414–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heikkinen AT, Friedlein A, Lamerz J, et al. Mass spectrometry-based quantification of CYP enzymes to establish in vitro/in vivo scaling factors for intestinal and hepatic metabolism in beagle dog. Pharm Res. 2012;29(7):1832–1842. doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0707-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tenmizu D, Endo Y, Noguchi K, et al. Identification of the novel canine CYP1A2 1117 C > T SNP causing protein deletion. Xenobiotica. 2004;34(9):835–846. doi: 10.1080/00498250412331285436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mise M, Yadera S, Matsuda M, et al. Polymorphic expression of CYP1A2 leading to interindividual variability in metabolism of a novel benzodiazepine receptor partial inverse agonist in dogs. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32(2):240. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scherr MC, Lourenco GJ, Albuquerque DM, et al. Polymorphism of cytochrome P450 A2 (CYP1A2) in pure and mixed breed dogs. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(2):184–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2885.2010.01243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whiterock VJ, Morgan DG, Lentz KA, et al. Phenacetin pharmacokinetics in CYP1A2-deficient beagle dogs. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40(2):228–231. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.041848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blaisdell J, Goldstein JA, Bai SA. Isolation of a new canine cytochrome P450 CDNA from the cytochrome P450 2C subfamily (CYP2C41) and evidence for polymorphic differences in its expression. Drug Metab Dispos. 1998;26(3):278–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roussel F, Duignan DB, Lawton MP, et al. Expression and characterization of canine cytochrome P450 2D15. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;357(1):27–36. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paulson SK, Engel L, Reitz B, et al. Evidence for polymorphism in the canine metabolism of the cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor, celecoxib. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27(10):1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lankford SM, Bai SA, Goldstein JA. Cloning of canine cytochrome P450 2E1 cDNA: identification and characterization of two variant alleles. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28(8):981–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tenmizu D, Noguchi K, Kamimura H. Elucidation of the effects of the CYP1A2 deficiency polymorphism in the metabolism of 4-cyclohexyl-1-ethyl-7-methylpyrido 2,3-d pyrimidine-2-(1h)-one (YM-64227), a phosphodiesterase type 4 inhibitor, and its metabolites in dogs. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34(11):1811. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.011213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tenmizu D, Noguchi K, Kamimura H, et al. The canine CYP1A2 deficiency polymorphism dramatically affects the pharmacokinetics of 4-cyclohexyl-1-ethyl-7-methylpyrido 2,3-D- pyrimidine-2-(1H)-one (YM-64227), a phosphodiesterase type 4 inhibitor. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34(5):800. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.008722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azuma R, Komuro M, Kawaguchi Y, et al. Comparative analysis of in vitro and in vivo pharmacokinetic parameters related to individual variability of GTS-21 in canine. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2002;17(1):75–82. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.17.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamimura H. Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450s in beagles: possible influence of CYP1A2 deficiency on toxicological evaluations. Arch Toxicol. 2006;80(11):732–738. doi: 10.1007/s00204-006-0100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whiterock VJ, Delmonte TA, Hui LE, et al. Frequency of CYP1A2 polymorphism in beagle dogs. Drug metabolism letters. 2007;1(2):163–165. doi: 10.2174/187231207780363688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aretz JS, Geyer J. Detection of the CYP1A2 1117C>T polymorphism in 14 dog breeds. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(1):98–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2885.2010.01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neff MW, Robertson KR, Wong AK, et al. Breed distribution and history of canine mdr1- 1Delta, a pharmacogenetic mutation that marks the emergence of breeds from the collie lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(32):11725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402374101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham MJ, Bell AR, Crewe HK, et al. mRNA and protein expression of dog liver cytochromes P450 in relation to the metabolism of human CYP2C substrates. Xenobiotica. 2003;33(3):225–237. doi: 10.1080/0049825021000048782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Locuson CW, Ethell BT, Voice M, et al. Evaluation of Escherichia coli membrane preparations of canine CYP1A1, 2B11, 2C21, 2C41, 2D15, 3A12, and 3A26 with coexpressed canine cytochrome P450 reductase. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37(3):457–461. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.025312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shou M, Norcross R, Sandig G, et al. Substrate specificity and kinetic properties of seven heterologously expressed dog cytochromes p450. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31(9):1161–1169. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.9.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sams RA, Muir WW. Effects of phenobarbital on thiopental pharmacokinetics in greyhounds. Am J Vet Res. 1988;49(2):245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sams RA, Muir WW, Detra RL, et al. Comparative pharmacokinetics and anesthetic effects of methohexital, pentobarbital, thiamylal, and thiopental in Greyhound dogs and non-Greyhound, mixed-breed dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46(8):1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson EP, Sams RA, Muir WW. Barbiturate anesthesia in greyhound and mixed-breed dogs: comparative cardiopulmonary effects, anesthetic effects, and recovery rates. Am J Vet Res. 1986;47(10):2105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Court MH. Anesthesia of the sighthound. ClinTechSmall AnimPract. 1999;14(1):38. doi: 10.1016/S1096-2867(99)80025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zoran DL, Riedesel DH, Dyer DC. Pharmacokinetics of propofol in mixed-breed dogs and greyhounds. Am J Vet Res. 1993;54(5):755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mandsager RE, Clarke CR, Shawley RV, et al. Effects of chloramphenicol on infusion pharmacokinetics of propofol in greyhounds. Am J Vet Res. 1995;56(1):95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Court MH, Hay-Kraus BL, Hill DW, et al. Propofol hydroxylation by dog liver microsomes: assay development and dog breed differences. Drug MetabDispos. 1999;27(11):1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]