Abstract

This research examined whether self-verification acts as a general mediational process of self-fulfilling prophecies. The authors tested this hypothesis by examining whether self-verification processes mediated self-fulfilling prophecy effects within a different context and with a different belief and a different outcome than has been used in prior research. Results of longitudinal data obtained from mothers and their adolescents (N = 332) indicated that mothers’ beliefs about their adolescents’ educational outcomes had a significant indirect effect on adolescents’ academic attainment through adolescents’ educational aspirations. This effect, observed over a six year span, provided evidence that mothers’ self-fulfilling effects occurred, in part, because mothers’ false beliefs influenced their adolescents’ own educational aspirations which adolescents then self-verified through their educational attainment. The theoretical and applied implications of these findings are discussed.

Keywords: Self-fulfilling prophecies, Self-verification, Educational attainment

Social psychological theory proposes that self-fulfilling prophecies and self-verification processes can intersect to influence social interactions. Most often, the literature has conceptualized the intersection of these processes in adversarial terms, proposing that self-verifying behaviors compete with behaviors that would otherwise bring about self-fulfilling prophecies (Madon et al., 2001; Major, Cozzarelli, Testa, & McFarlin, 1988; McNulty & Swann, 1994). That is, even though perceivers may channel their interactions with targets in ways that could elicit confirmatory behavior from them via a self-fulfilling prophecy, targets are rarely so malleable that they simply become what perceivers expect them to be. Targets also self-verify during social interactions by convincing perceivers to adopt beliefs that match their own self-views (Swann, 1987). Although several studies have shown that self-verification processes do indeed weaken perceivers’ self-fulfilling effects (Madon et al., 2001; Major et al., 1988; McNulty & Swann, 1994), that need not always be the case.

It is also conceivable that self-verification processes may facilitate the occurrence of self-fulfilling prophecies by mediating the influence that perceivers’ false beliefs have on targets’ behaviors (Brophy, 1983; Darley & Fazio, 1980; Madon et al., 2008; Snyder & Swann, 1978). According to this line of reasoning, the false beliefs that perceivers hold about targets affect how targets view themselves. Because such changes in targets’ self-views are not behavioral, they would not reflect a self-fulfilling prophecy per se. However, if targets internalize these self-views into their self-concepts, then they may engage in self-verification processes that could cause them to behaviorally confirm perceivers’ initially false beliefs over extended periods of time. The present research tested this idea by examining whether mothers’ inaccurate beliefs about their adolescents’ educational outcomes altered their adolescents’ subsequent beliefs about how much schooling they would likely obtain and whether those altered views about the self influenced adolescents’ post-secondary educational attainment. We begin by discussing research relevant to the mediation of self-fulfilling prophecies after which we present the theoretical and empirical basis underlying the hypothesis.

Mediators of the Self-Fulfilling Prophecy Process

A self-fulfilling prophecy occurs when a perceiver holds an inaccurate belief about a target, treats the target in a manner consistent with the inaccurate belief, and by so doing, elicits from the target behavior that is consistent with the originally inaccurate belief (Merton, 1948). Much of the literature examining the self-fulfilling prophecy process has addressed the mediating behaviors that serve to communicate or transmit perceivers’ inaccurate beliefs to targets (Brophy, 1983; Harris & Rosenthal, 1985; Rosenthal, 1973). This literature has been summarized in several comprehensive reviews (Brophy, 1983; Harris & Rosenthal, 1985; Rosenthal, 1973). Rosenthal (1973) and Brophy (1983) reviewed mediators of teachers’ self-fulfilling effects on students’ academic outcomes. Rosenthal focused on broad dimensions of behavior that operate to transmit teachers’ inaccurate beliefs to students including (1) climate – non-verbal behaviors that communicate the degree to which teachers like and accept students, (2) input – the amount and difficulty of material that teachers provide students, (3) output – the opportunities that teachers create for students to develop and practice their skills, and (4) feedback – the kind of feedback that teachers give students. Brophy (1983) focused on specific behavioral mediators of teachers’ self-fulfilling effects. These included, for example, waiting less time for low-expectancy students to respond to questions, reinforcing low expectancy students for incorrect answers and poor behavior, and providing low expectancy students with less praise relative to high expectancy students. Harris and Rosenthal (1985) performed a meta-analysis of 136 studies through which they identified 15 specific behavioral mediators that influenced targets’ subsequent outcomes, including a positive climate, praise, eye contact, smiles, speech rate, and frequency of interactions, among others. As evidenced above, the literature on mediators of the self-fulfilling prophecy has furthered psychology’s understanding of the ways through which inaccurate beliefs shape reality by identifying behaviors that mediate the perceiver-target interaction sequence.

Nonetheless, this literature has also been criticized for focusing on behavioral mediators that are limited in their potential to operate across contexts and social relationships (Harris, 1993; Harris & Rosenthal, 1985). For example, the vast majority of extant research addressing the mediation of self-fulfilling prophecies has focused on teacher – student relations (Harris & Rosenthal, 1985). However, as Harris (1993) has pointed out, the behavioral mediators that transmit teachers’ self-fulfilling effects in the classroom may not necessarily transmit the self-fulfilling effects of other perceivers or operate in other settings such as getting acquainted situations, dating, home life, workplace, medical settings, and courtrooms. This fact has led to a call for research aimed at explaining how self-fulfilling prophecies operate across a broader spectrum of life situations (Harris, 1993; Harris & Rosenthal, 1985).

In an initial attempt to answer this call, Madon and colleagues (2008) examined the extent to which three social psychological processes mediated self-fulfilling prophecies, including self-verification, informational conformity, and modeling. Madon et al. examined these processes with respect to the mother-child relationship using adolescents’ alcohol use as the outcome variable. Their findings provided the strongest support for self-verification processes (Swann, 1987). Across adolescence, mothers’ inaccurate beliefs predicted their adolescents’ subsequent alcohol use through adolescents’ own beliefs about their likelihood of drinking alcohol in the future. This pattern suggested that adolescents had internalized their mothers’ inaccurate beliefs about their likelihood of drinking alcohol and then self-verified those beliefs through their subsequent alcohol use.

Self-Verification as a General Mediator of Self-Fulfilling Prophecies

Although Madon et al. (2008) observed their results with respect to adolescent alcohol use, self-views are often regarded as predictors of important outcomes (for a review, see Swann, Chang-Schneider, & McClarty, 2007). Accordingly, it is possible that the tendency for self-verification processes to mediate self-fulfilling prophecy effects could reflect a general process that operates across contexts (Snyder, 1984; Snyder & Swann, 1978). Indeed, such a hypothesis is consistent with a long history of theorizing about the underlying mechanisms that produce self-fulfilling prophecies. For example, Brophy (1983) proposed that “…differential teacher behavior communicates to each individual student something about how he or she is expected to behave in the classroom and perform on academic tasks. If teacher treatment is consistent over time, and if students do not actively resist or change it, it will likely affect student self-concept…Ultimately, this will make a difference in student achievement and other outcomes…” (p. 639 – 640). Darley and Fazio (1980) hypothesized that “…the target may accept the perceiver’s impression and come to believe it…In such cases, confirmatory behavior from the target may occur” (p. 875). Snyder (1984) proposed that “If internalization occurs, the person then may act on this new self-concept in contexts beyond those that include the individual who originally initiated the behavioral confirmation process” (p. 256–257; also see Snyder & Swann, 1978). Similar ideas are echoed in the works of other prominent theorists as well (e.g., Eccles et al., 1983; McNulty & Swann, 1994), providing a strong theoretical basis on which to predict that self-verification may be a general process that mediates self-fulfilling prophecies across contexts.

However, there is little in the way of empirical research bearing on this hypothesis. In fact, the extant literature includes only one relevant study other than Madon et al. (2008). Snyder and Swann (1978) demonstrated that targets’ tendency to confirm perceivers’ inaccurate beliefs carried over into a subsequent interaction with a new perceiver when targets were experimentally induced with the attribution that their prior confirmatory behavior reflected their own dispositional qualities. This finding is important because it suggests that people who internalize another’s false belief about them may subsequently behaviorally confirm that internalized belief.1 However, the potential generality of this process requires further empirical support from studies that are performed across a variety of contexts and which use a variety of beliefs and outcomes.

Accordingly, the current study tested whether self-verification processes mediated self-fulfilling prophecies within a different context and with a different belief and a different outcome than has been used in any prior research. Specifically, we examined whether mothers’ inaccurate beliefs about their adolescents’ educational outcomes altered their adolescents’ educational aspirations and whether those altered views about the self influenced adolescents’ post-secondary educational attainment. Our focus on adolescents’ educational attainment fits nicely with a long tradition within the self-fulfilling prophecy literature to address the potential influence that inaccurate beliefs have on adolescents’ educational and occupational opportunities (e.g., Cooper, Findley, & Good, 1982; Doyle, Hancock, & Kifer, 1972; Jussim, 1989; Jussim & Eccles, 1992; Madon, Jussim, & Eccles, 1997; Madon et al., 2001; Palardy, 1969; Rist, 1970; Seaver, 1973; Smith, Jussim, & Eccles, 1999; Smith et al., 1998; Sutherland & Goldschmid, 1974; West & Anderson, 1976; Williams, 1976).

It also compliments an impressive body of literature examining relations among parents’ beliefs about their children’s achievement, self-concepts of ability, and educational outcomes (for reviews, see Eccles et al., 1991; Eccles-Parsons, Adler, & Kaczala, 1982; Jacobs, Chin, & Bleeker, 2006). Although this literature is not typically framed in terms of self-fulfilling prophecies, it nonetheless provides an important context in which to understand the unique contributions of the current research as it relates to adolescents’ educational outcomes. Central to our focus are studies showing that (1) parents’ beliefs about their children’s academic performance predict their children’s subsequent self-concepts of ability (e.g., Bleeker & Jacobs, 2004; Eccles-Parsons et al., 1982; Entwisle & Hayduk, 1982), career self-efficacy (Bleeker & Jacobs, 2004), academic performance (Alexander & Entwisle, 1988; Entwisle, Alexander, & Olson, 2005), and eventual academic attainment (Entwisle et al., 2005); (2) Children’s educational aspirations and self-concepts of ability predict the high school courses in which they enroll (e.g., Eccles-Parsons et al., 1983), their level of engagement in class (Entwisle & Webster, 1972), and their educational attainment (Marjoribanks, 1991; 2005) and (3) Children’s self-concepts of ability mediate the relation between parents’ beliefs about their children’s academic performance and children’s career self-efficacy (Bleeker & Jacobs, 2004).

The present research contributes to the above literatures by examining the extent to which self-verification processes (assessed via adolescents’ educational aspirations) mediate the self-fulfilling effect that mothers have on their adolescents’ educational attainment. Moreover, because we examined this mediational process across a six year time frame – substantially longer than any other previous study on this topic – our research also addressed whether this process can produce long-lasting changes in targets’ behavior, as has been hypothesized in the theoretical literature (e.g., Snyder, 1984).

Overview of Research

This research examined whether self-verification processes mediated self-fulfilling prophecy effects with longitudinal data obtained from 332 mother-child dyads. Assessments occurred at four points in time: while adolescents were in the 7th grade, 11th grade, 12th grade, and one year following their graduation from high school. Although previously published articles examining self-fulfilling prophecies have used data obtained from the mothers and adolescents examined in the current study (Madon, Guyll, & Spoth, 2004; Madon et al., 2008; Madon, Guyll, Spoth, Cross, & Hilbert, 2003; Madon, Guyll, Spoth, & Willard, 2004; Madon, Willard, Guyll, Trudeau, & Spoth, 2006; Willard, Madon, Guyll, Spoth, & Jussim, 2008), those studies focused on beliefs and outcomes relevant to alcohol use or hostility. The variables examined in the current study have not previously been examined in any prior research addressing self-fulfilling prophecies; the program of research of which this study is a part has examined parenting effects on school engagement and academic performance (Spoth et al., 2008), but not effects of parents’ beliefs about their adolescents’ educational attainment.

Analytic Framework

Two existing models provided the analytic framework for our research. Because it is beyond the scope of this article to describe these models in detail, we focus here on their core elements as they pertain to our research and refer interested readers to the source articles for additional information (Eccles et al., 1983; Jussim, 1991). According to the model of parent socialization (Eccles et al., 1983), parents’ beliefs have the potential to influence their children’s subsequent educational outcomes. The model proposes that parents’ beliefs arise from the characteristics of parents as well as the characteristics of their children and family, and include both general beliefs about the world (e.g., stereotypes, biases, child rearing beliefs, values, etc.) and specific beliefs about their children (e.g., performance expectations, competencies and skills, interests, etc.). The model further proposes that parents communicate their beliefs to their children through specific parenting behaviors (e.g., training of personal values, guidance, facilitation of participation in certain activities, etc.) and, by so doing, influence their children’s subsequent beliefs (e.g., values, world view), self-views (e.g., self-concepts of ability), and behaviors (e.g., performance, activity choices, persistence, etc.). Of particular relevance to our research is the prediction that children’s self-views mediate the influence of parents’ beliefs on children’s educational outcomes.

The reflection-construction model of social perception (Jussim, 1991) was specifically designed to show relations involved in naturally-occurring self-fulfilling prophecies between perceivers and targets. The model proposes that background predictors of targets’ behaviors influence both targets’ subsequent behaviors as well as perceivers’ beliefs about targets. The model defines perceivers’ beliefs as accurate to the extent that they are predicted by targets’ background variables and as erroneous to the extent that they are not predicted by targets’ background variables. The conceptual distinction between the accurate and inaccurate portion of perceivers’ beliefs is important for two reasons. First, in the naturalistic environment, perceivers typically have at least some valid information about targets on which to base their beliefs (Madon et al., 1998). Second, because only erroneous beliefs can be self-fulfilling (Merton, 1948), the availability of valid information reduces the potential for perceivers to influence targets’ behaviors by means of self-fulfilling prophecies. Thus, according to the reflection-construction model, a self-fulfilling prophecy effect corresponds to the unique relation between perceivers’ beliefs and targets’ subsequent behaviors after accounting for targets’ background variables.

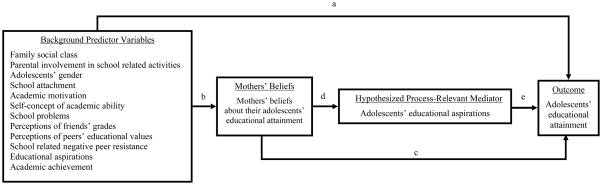

Figure 1 presents an adaptation of the reflection-construction model for the relations examined in our research. Consistent with the model, background predictor variables of adolescents’ educational attainment may influence both adolescents’ actual educational attainment (Path a) and mothers’ beliefs about their adolescents’ educational outcomes (Path b). Mothers’ beliefs are considered accurate to the extent that they are predicted by these background predictor variables. Accordingly, the accurate portion of the relationship between mothers’ beliefs and adolescents’ educational attainment is entirely contained in the effect represented by Path a (Jussim, 1991). Path c represents the ability of the erroneous portion of mothers’ beliefs to influence adolescents’ educational attainment by means of a self-fulfilling prophecy (Jussim, 1991). Therefore, consistent with the tenets of the reflection-construction model, we operationalized self-fulfilling prophecy effects as the unique relation between mothers’ beliefs and adolescents’ educational attainment after accounting for the background predictor variables of adolescents’ educational attainment.

Figure 1.

Adapted reflection-construction model (Jussim, 1991). This model shows predicted causal relations among background predictor variables of adolescents’ educational attainment, mothers’ beliefs about their adolescents’ educational attainment, and adolescents’ actual educational attainment. According to the model, the background predictor variables influence adolescents’ educational attainment (Path a) and mothers’ beliefs (Path b). Mothers’ beliefs can also influence their adolescents’ educational attainment through self-fulfilling prophecies (Path c + de). These self-fulfilling prophecy effects may be mediated by self-verification processes (Path de).

Because the accurate estimation of mothers’ self-fulfilling effects on adolescents’ educational attainment depends on the quality of the background predictor variables included in the model, the background variables used in this study include a comprehensive set of predictors of adolescents’ educational attainment including school reports of adolescents’ standardized test scores and grade point average (GPA), parents’ reports of the family’s social class, parental involvement in their adolescents’ school-related activities, plus adolescents’ gender and adolescents’ reports of their school attachment, academic self-concept, academic motivation, school problems, friends’ grades, peers’ educational values, school related negative peer resistance, and beliefs about their own educational attainment. Finally, Path de shows the potential for self-verification processes to mediate mothers’ self-fulfilling effects on their adolescents’ educational attainment.

Method

Participants

Data were obtained from families who participated in the Capable Families and Youth Study (Spoth, Redmond, Trudeau, & Shin, 2002), a longitudinal randomized-controlled intervention trial focusing on the prevention of adolescent substance use and other problem behaviors. Adolescents in the Capable Families project were enrolled in 36 schools in 22 contiguous counties in Iowa. Schools were selected on the basis of school lunch program eligibility (20% or more of households within 185% of the federal poverty level in the school district), school district size (1,200 or fewer), and having all middle school grades taught at a single location. The current study used data obtained from a sub-sample of 332 mothers and their adolescent children who had valid data on all of the variables used in the analyses. Only one adolescent from each family provided data. There were 158 girls and 174 boys in the sample, including 330 European Americans, 1 African American and 1 adolescent whose ethnicity was categorized as “other”. At wave 1, mothers’ mean age was 40 and adolescents’ mean age was 12.

Procedures

The current research used questionnaire responses that were assessed while adolescents were in the 7th, 11th and 12th grades, and one year after having graduated from high school. For the first three waves, research staff administered written questionnaires to participating family members who completed them in separate rooms of their residence. For the final wave of data collection, research staff interviewed the adolescents on the phone. Research staff also examined archival school records to obtain adolescents’ standardized test scores and GPA.

Measures

The questionnaires assessed a large number of variables related to family, peers, and school. The current study used variables that pertained to: (1) mothers’ beliefs about their adolescents’ educational outcomes; (2) school reports of adolescents’ academic performance (i.e., standardized test scores and GPA); (3) parents’ reports of their family’s social class and their involvement in their adolescents’ school-related activities; (4) adolescents’ gender, and; (5) adolescents’ reports of their school attachment, self-concept of academic ability, academic motivation, school problems, perceptions of their friends’ grades, perceptions of their peers’ educational values, school related negative peer resistance, educational aspirations and actual educational attainment. We next discuss each of these variables in detail and provide reliability information in terms of Cronbach’s alpha. All variables were assessed at wave 1 (7th grade) except where noted. Higher values indicate a higher level of the concept.

Mothers’ beliefs

Mothers’ beliefs about their adolescents’ academic outcomes was assessed with two items. For one item, mothers responded to the question “Which of the following is closest to the grades this child usually gets in school?”. Mothers’ responded using a 9-point scale with anchors 1 (mostly A’s) through 9 (mostly F’s). Responses were reversed scored. For the other item, mothers answered the question “How far do you expect this child to go in school?”. Mothers responded to this question on a 6-point scale with anchors 1 (less than high school) through 6 (advanced degree – e.g., Law, Master’s degree, Ph.D., Medicine, Veterinary Medicine, or Dentistry). To combine responses into a single variable, we rescaled the 6-point scale responses into a 9-point scale (i.e., 1 → 1; 2 → 2.6; 3 → 4.2; 4 → 5.8; 5 → 7.4; 6 → 9) and then averaged responses to both questions to create one score per adolescent (α = .67).

School reports of adolescents’ academic performance

Schools provided adolescents’ 6th grade Iowa Test of Basic Skills (ITBS) composite score and 6th grade year-end grade point average (GPA).

Family social class

Family social class was estimated with family income and parental education. Family income was assessed with parents’ reports of their household’s total, pretax income, including wages, salaries, business income, dividends, interest, loans, gifts of money, and all forms of government assistance obtained by any member of the household. Parental education was assessed through parents’ reports of the highest educational level or degree they had attained on a scale that ranged from 0 through 20 (e.g., 0 = no education; 12 = high school diploma or general equivalency diploma; 16 = bachelor’s degree; 18 = master’s degree; 20 = PhD, MD, JD, etc.). Approximately 98% percent of parents had completed high school or its equivalent. When data from both mothers and fathers were available, their responses were averaged for income as were their responses for parental education. The correlation between family income and parental education was r = .33.

Parental involvement in school-related activities

Parental involvement in adolescents’ school-related activities was assessed with seven parent reported items (α = .69) that are available in the Appendix. These items assessed parental involvement with respect to adolescents’ school work and school events. Because the items comprising this measure used different response scales (i.e., 4-point, 5-point, and 6-point response scales), we combined responses by rescaling the 4-point scale (i.e., 1 → 1; 2 → 2.67; 3 → 4.33; 4 →6) and the 5-point scale (i.e., 1 → 1; 2 → 2.25; 3 → 3.5; 4 → 4.75; 5 →6) into a 6-point scale. Responses were reverse scored as necessary. When data from both mothers and fathers were available, their responses were averaged to create one variable per adolescent.

Adolescents’ school attachment

Adolescents answered five questions that assessed the extent to which they felt attached to school. One item asked adolescents to think about school last year (grade 6) and to then respond to the statement “School was fun”. The remaining four items started with the question stem “How true is each of the following statements for you now?” (a) “I like school a lot”, (b) “I don’t feel like I really belong at school”, (c) “I feel very close to at least one of my teachers”, and (d) “I get along well with my teachers”. Adolescents responded to all five of these items on a 5-point scale with anchors 1 (never true) through 5 (always true). Responses were reverse scored as necessary and averaged to create one score per adolescent (α = .75). Two of the items that were used to assess school attachment have been used by a previously published article to assess school engagement (Spoth, Randall, & Shin, 2008). These items included “I like school a lot” and “I don’t feel like I really belong at school.”

Adolescents’ self-concept of academic ability

Adolescents’ self-concept of academic ability was assessed with seven items. Two items asked adolescents to think about school last year (grade 6) and then to respond to the statements: (a) “Schoolwork was really hard” and (b) “I did not do as well as I should have in school”. These items were measured with a 5-point scale with anchors 1 (never true) through 5 (always true). The other five questions started with the stem “Indicate how often you do the following in each situation:” (a) “When I have to write a paper or do a reading assignment, I get kind of worried about it”, (b) “I find it hard to take tests in school”, (c) “I have gotten pretty good grades during the past year”, (d) “I find it difficult to express my ideas in writing”, and (e) “I have trouble understanding things that are given for reading assignments”. These five items were measured with a 5-point scale with anchors 1 (never) through 5 (always). Responses were reverse scored as necessary and then averaged to create one variable per adolescent (α = .69).

Adolescents’ academic motivation

Adolescents’ academic motivation was assessed with six questions that started with the stem “How true is each of the following statements for you now?” (a) “I try hard at school”, (b) “I finish my homework”, (c) “Grades are very important to me”, (d) “School bores me”, (e) “I do most of my school work without help from others”, and (f) “Even when there are other interesting things to do, I keep up my school work”. All six items were measured with a 5-point scale with anchors 1 (never true) through 5 (always true). Responses were reverse scored as necessary and then averaged to create one score per adolescent (α = .76). Our measure of adolescents’ academic motivation was adapted from a previously published scale assessing school engagement (Spoth, Randall, & Shin, 2008).

Adolescents’ school problems

Adolescents’ school problems were assessed with two measures that we refer to as general behavioral problems and specific school problems. General behavioral problems was assessed with two yes-no questions that started with the stem “Did these things happen to you during the past 12 months?”: (a) “You got into trouble with classmates at school” and (b) “You got into trouble at school”. Responses were coded as 1 (‘Yes’) and 2 (‘No’). Responses to the items assessing general behavioral problems were reversed scored and then summed to create one score per adolescent that could range from 2 to 4. Specific school problems was assessed with seven questions that started with the stem “In the past year, how many times have you been in trouble at school for…”: (a) “Disrupting class?”, (b) “Not turning in your homework on time?”, (c) “Talking back to the teachers?”, (d) “Not paying attention in class?”, (e) “Skipping class?”, (f) “Bringing a weapon to school?”, and (g) “Breaking other school rules?”. Adolescents responded to these questions on 5-point scales with anchors 1 (never) through 5 (more than five times). Responses to the items assessing specific school problems were reverse scored and then averaged to create one score per adolescent (α = .77).

Adolescents’ perceptions of friends’ grades

To assess adolescents’ perceptions of their friends’ grades, they were asked to think about their closest friends and to indicate agreement with the following statement: “These friends get bad grades in school.” Adolescents responded to this statement on a 5-point scale with anchors 1 (strongly agree) through 5 (strongly disagree).

Adolescents’ perceptions of peers’ educational values

Adolescents’ perceptions of their peers’ educational values was assessed with four items that began with the stem “Please read the following list of things that you may or may not have done. Even if you have never done any of these things, please try to imagine what your friends would think if…”: (a) “…you took part in school activities like band, choir, clubs or school dances”, (b) “…you took part in school sports”, (c) “…you worked hard to get good grades in school”, and (d) “…you saved your money to go to college”. Responses to these items were assessed on a 3-point scale with anchors 1 (not cool) through 3 (cool). Responses were averaged to create one score per adolescent (α = .62).

Adolescents’ school related negative peer resistance

Adolescents’ school related negative peer resistance was assessed with six items. Four of these items used the following stem “Sometimes your friends may want you to do things that could get you into trouble. How well can you resist pressure from your friends to do the following things?”: (a) “Skip school without an excuse”, (b) “Cheat on a test”, (c) “Lie to teachers”, and (d) “Do things at school that can get you into trouble”. Responses were measured on a 4-point scale with anchors of 1 (not well at all) through 4 (pretty well). The remaining two questions used the stem “Imagine one of your friends asked you to skip school. How likely would you be to do each of these things?”: (a) “Go with the friend” and (b) “Make up an excuse for not going with your friend”. Responses to these items were measured on a 5-point scale with the anchors 1 (very likely) through 5 (very unlikely), with the last question reversed scored. To combine responses into a single variable, we rescaled the 4-point scale responses (i.e., 1 → 1; 2 → 2.33; 3 → 3.67; 4 →5) into a 5-point scale. Responses were then averaged to create one score per adolescent (α = .76).

Adolescents’ educational aspirations

Adolescents’ educational aspirations were assessed with the following question: “If you could go as far as you wanted in school, how much education would you like to have?”. Responses were measured with a 6-point scale with anchors 1 (less than high school) through 6 (advanced degree – e.g., Law, Master’s degree, Ph.D., Medicine, Veterinary Medicine, or Dentistry). Adolescents responded to this item three times, once during the 7th grade and then again during the 11th and 12th grades. Adolescents’ 7th grade responses were included as a background predictor variable. Adolescents’ 11th and 12th grade responses were averaged to create one variable per adolescent (α = .80) that served as the process-relevant mediator.2

Adolescents’ educational attainment

Adolescents’ educational attainment was assessed one year after they graduated from high school with a question that tapped conceptual differences in their level of schooling (e.g., Entwisle et al., 2005): “Which of the following best describes the kind of school you attended most since last June?”. Responses were measured with a three point scale with anchors of 1 (High school or high school equivalent study - e.g. ED), 2 (Trade school, business school, community college), and 3 (four-year college or university). Approximately 2% of adolescents reported that they had last attended high school or received high school equivalent study, 45% reported that they had last attended trade school, business school, or community college, and 53% reported that they had last attended a 4-year college or university.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations among the individual level variables. As indicated in Table 1, there were 332 families included in the analyses – i.e., all families who provided data for all variables examined in this research. An additional 304 families had data available from wave 1, but failed to complete the required assessments at subsequent waves of data collection. This corresponds to an attrition rate of 47.8% – a rate that is not excessive for a community sample, followed across six years, at multiple assessment waves. Retained adolescents tended to have more favorable scores on the variables assessed at wave 1. However, these differences do not threaten the statistical conclusion validity of the present analyses because they would contribute to restriction of range for these variables, thereby increasing the difficulty of detecting relationships and causing the findings of this research to be conservative.

Table 1.

Zero Order Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations at Wave 1 for the Background Predictor Variables (N = 332)

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Family income | --- | |||||||||||||||

| (2) Parental education | .33** | --- | ||||||||||||||

| (3) Parental involvement | .07 | .25** | --- | |||||||||||||

| (4) Mothers’ beliefs | .08 | .30** | .02 | --- | ||||||||||||

| (5) School attachment | .03 | .13* | .16** | .32** | --- | |||||||||||

| (6) Adolescent gendera | .03 | .00 | −.13* | .17** | .15** | --- | ||||||||||

| (7) Academic motivation | .00 | .07 | .08 | .39** | .68** | .15** | --- | |||||||||

| (8) Self-concept of academic ability | .06 | .08 | −.00 | .40** | .36** | .05 | .42** | --- | ||||||||

| (9) General behavioral problems | −.03 | −.15* | −.08 | −.13* | −.25** | −.18** | −.25** | −.17** | --- | |||||||

| (10) Specific school problems | −.01 | −.11* | −.10 | −.23** | −.34** | −.23** | −.46** | −.24** | .48** | --- | ||||||

| (11) Friends’ grades | .08 | .11* | .16** | .11** | .33** | .09 | .32** | .22** | −.20** | −.14** | --- | |||||

| (12) Peers’ educational values | −.01 | .04 | .09 | .22** | .36** | .22 | .37** | .22** | −.22** | −.22** | .32** | --- | ||||

| (13) School related negative peer | −.02 | .12* | −.03 | .25** | .24** | .05 | .20** | .19** | −.12* | −.21** | .12* | .11* | --- | |||

| (14) Educational aspirations i | .06 | .16** | .06 | .50** | .28** | .18** | .25** | .23** | −.11* | −.20** | .13* | .26** | .18** | --- | ||

| (15) GPA | .09 | .22** | .01 | .68** | .24** | .14* | .37** | .39** | −.15** | −.30** | .07 | .17** | .22** | .28** | --- | |

| (16) ITBS | .08 | .27** | −.03 | .65** | .22** | .00 | .25** | .43** | −.01 | −.10 | −.06 | .07 | .23** | .31** | .63** | --- |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Mean | 48,576b | 13.61 | 4.64 | 7.14 | 3.74 | 48%c | 4.14 | 3.63 | 1.18 | 1.20 | 4.27 | 2.70 | 4.46 | 5.06 | 3.20 | 53.22 |

| SD | 22,767 | 1.62 | .51 | 1.32 | .79 | .53 | .66 | .33 | .58 | .81 | .33 | .68 | 1.16 | .65 | 25.67 | |

Note. The following variables reflect parents’ reports: family income, parental education, parental involvement, and mothers’ beliefs. Parental involvement refers to parental involvement in their adolescents’ school-related activities. Mothers’ beliefs refer to mothers’ beliefs about their adolescents’ academic outcomes. The following variables reflect adolescents’ reported perceptions: school attachment, academic motivation, self-concept of academic ability, general behavioral problems, specific school problems, friends’ grades, peers’ educational values, school related negative peer resistance, educational aspirations. GPA and ITBS scores reflect school reports.

Boys were coded as 1 and girls were coded as 2.

The median income of families at wave 1 was $43,750.

Value reflects percentage of children who were girls. The zero-order correlation between mothers’ beliefs and the process-relevant mediator of adolescents’ educational aspirations was .51, p < .01. The zero-order correlation between mothers’ beliefs and the outcome of adolescents’ educational attainment was .55, p < .01. The zero-order correlation between the process-relevant mediator of adolescents’ educational aspirations and the outcome of adolescents’ educational attainment was .48, p < .01.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

Analytic Plan

We performed a three step hierarchical regression analysis to test for mothers’ self-fulfilling prophecy effects and to provide an initial examination of adolescents’ educational aspirations as a mediator of this effect. Because the 332 adolescents were clustered within 36 school districts, we performed the regression analysis in the context of a multilevel model using SAS PROC MIXED in which we included school district as a higher-level random effect, used restricted maximum likelihood estimation, and specified a variance components covariance structure. Traditional data analytic procedures are inappropriate for clustered data because they assume independence of individual observations and, as a result, tend to underestimate standard errors and bias significance tests toward rejection of the null hypothesis (Cochran, 1977; Kreft de Leeuw, 1998).

The individual level portion of the analysis consisted entirely of fixed effects and was conducted in three steps. The first step included all background variables in order to account for the accuracy-based portion of mothers’ beliefs with respect to adolescents’ educational attainment which was assessed six years after mothers’ beliefs were assessed.3 In the second step, mothers’ beliefs about their adolescents’ academic outcomes was added to the analysis. The ability of mothers’ beliefs to predict unique variance in adolescents’ educational attainment would represent a self-fulfilling prophecy because this predictive relationship would be beyond that associated with accuracy, which was removed by the inclusion of the background predictors included in the first step (Jussim, 1991). At step three, the process-relevant mediator of adolescents’ educational aspirations was added to the analysis. Because the effect of a mediator on an outcome is more proximal than the antecedent cause, inclusion of adolescents’ educational aspirations should both explain additional variance in their educational attainment and lead to a decrease in the coefficient associated with mothers’ beliefs (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Results suggestive of mediation were subsequently examined through a follow-up analysis (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) that explicitly tested the significance of a specific indirect effect of mothers’ beliefs on adolescents’ educational attainment through the process-relevant mediator of adolescents’ educational aspiration.

Main Analyses

Non-independence of observations within schools

Results of the multi-level model are presented in Table 2. The school-level random effects portion of the analysis revealed little non-independence of individual-level observations. Specifically, the intraclass correlation coefficient indicated that clustering within the 36 schools accounted for only 1.1% of the variance, which did not approach significance (z = .37, p = .35).

Table 2.

Relationships of the Background Predictors, Mothers’ Beliefs, and Adolescents’ Educational Aspirations with the Outcome of Adolescents’ Educational Attainment

| Variables | β |

|---|---|

| Step 1: Background Predictors: | |

| Family income | .05 |

| Parental education | .20*** |

| Parental involvement | −.07 |

| School attachment | −.08 |

| Academic motivation | .14* |

| Adolescents’ gender | .06 |

| Self-concept of academic ability | −.01 |

| General behavioral problems | −.15** |

| Specific school problems | −.03 |

| Friends’ grades | .08 |

| Peers’ educational values | −.03 |

| School related negative peer resistance | −.06 |

| Educational aspirations | .04 |

| GPA | .25** |

| ITBS | .23** |

| Step 2: Self-fulfilling Prophecy: | |

| Mothers’ beliefs | .33*** |

| Step 3: Mediation: | |

| Adolescents’ educational aspirations | .26*** |

Note. (N = 332). Values are the effect of each variable on the outcome of adolescents’ educational attainment. All values correspond to those obtained when the variables were first entered in the model. The following variables reflect parents’ reports: family income, parental education, parental involvement, and mothers’ beliefs. Parental involvement refers to parental involvement in their adolescents’ school-related activities. Mothers’ beliefs refer to mothers’ beliefs about their adolescents’ academic outcomes. The following variables reflect adolescents’ reported perceptions: school attachment, academic motivation, self-concept of academic ability, general behavioral problems, specific school problems, friends’ grades, peers’ educational values, school related negative peer resistance, educational aspirations. GPA and ITBS scores reflect school reports. The background predictors and mothers’ beliefs were assessed at wave 1. The process-relevant mediator of adolescents’ educational aspirations was assessed while adolescents were in the 11th and 12th grades. The outcome of adolescents’ educational attainment was assessed one year after the adolescents’ had graduated from high school. The indirect effect of mothers’ beliefs on adolescents’ educational attainment through adolescents’ educational aspirations was .13 in terms of a standardized coefficient.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p ≤ .001.

Regression analysis Step 1: Background predictors

In the first step of the regression analysis, we accounted for background predictors of adolescents’ educational attainment by entering all of the background predictors (i.e., school reports of adolescents’ ITBS scores and GPA, parents’ reports of the family’s social class, and parental involvement in school-related activities, plus adolescents’ gender and reports of their school attachment, self-concept of academic ability, academic motivation, general and specific behavioral problems, friends’ grades, perception of peers’ educational values, and school-related negative peer resistance). The background predictors collectively explained 33.8% of the individual-level variance in adolescents’ educational attainment. Furthermore, five of the background predictors evidenced significant unique relationships with adolescents’ educational attainment, including parental education (β = .20) and adolescents’ academic motivation (β= .14), general behavioral problems (β = −.15), ITBS scores (β = .23), and GPA (β =.25), all ps < .05.

Regression analysis Step 2: Self-fulfilling prophecy

We next tested for a self-fulfilling prophecy effect by adding mothers’ beliefs about their adolescents’ educational outcomes to the variables included in Step 1. As indicated in Table 2, the presence of a self-fulfilling prophecy effect was supported. Mothers’ beliefs significantly predicted the outcome of adolescents’ educational attainment, β = .33, p < .001 above and beyond that predicted by the background predictors.

Regression analysis Step 3: Mediation

To provide a preliminary examination of mediation, we next added adolescents’ educational aspirations to the analysis. Results were consistent with the hypothesis that adolescents’ educational aspirations mediated the self-fulfilling effects of mothers’ beliefs on their educational attainment. Specifically, adolescents’ educational aspirations were significantly related to their educational attainment (β = .26, p < .001). Moreover, the addition of adolescents’ educational aspirations to the analysis resulted in a reduction in the regression coefficient corresponding to mothers’ beliefs, from β = 33, p < .001 to β = 25, p < .001.

Follow-Up Test of Mediation

Results of the hierarchical regression analysis was consistent with the idea that self-verification processes mediated at least a portion of mothers’ self-fulfilling effects on adolescents’ subsequent educational attainment. However, it is unknown whether adolescents’ educational aspirations accounted for a statistically significant portion of the self-fulfilling prophecy effect. Accordingly, we used Preacher and Hayes’ (2008) bootstrapping method for assessing indirect effects in the context of models that include multiple covariates in order to explicitly test the significance of the indirect effect of mothers’ beliefs on adolescents’ educational attainment via adolescents’ educational aspirations, while simultaneously controlling for all of the background predictors. Simulation studies have indicated that the bootstrapping method performs better and has substantially more power than traditional methods which utilize the Normal Theory Method (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007; MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). Following procedures recommended by Preacher & Hayes, the analysis entailed randomly selecting with replacement 5,000 bootstrap samples from the dataset.

According to the self-verification hypothesis, mothers’ false beliefs about their adolescents’ educational outcomes alter adolescents’ educational aspirations, and these altered self-views then influence adolescents’ actual educational attainment. The existence of a significant indirect effect of mothers’ beliefs on the outcome of adolescents’ educational attainment via adolescents’ educational aspirations would support the hypothesized mediational process. Consistent with the self-verification hypothesis, results indicated that the indirect effect of mothers’ beliefs on adolescents’ educational attainment through adolescents’ educational aspirations was significant, β = .13, p < .01. This result suggests that mothers’ self-fulfilling effects occurred, in part, because mothers’ false beliefs about their adolescents’ educational outcomes influenced adolescents’ own educational aspirations which they then self-verified through their educational attainment. The fact that mothers’ beliefs continued to significantly predict adolescents’ educational attainment after adolescents’ educational aspirations were included in the analysis (as reported above in Step 3) indicates that adolescents’ educational aspirations were partial mediators of the entire self-fulfilling prophecy effect.

At this point it is important to further note that the mediational model was tested using longitudinal data, temporally structured so as to be consistent with the hypothesized process. Specifically, whereas the causal agent of mothers’ beliefs was assessed when adolescents were in the 7th grade, the process-relevant mediator of adolescents’ educational aspirations was assessed four and five years later when adolescents were in the 11th and 12th grades, respectively, and the outcome of adolescents’ educational attainment was assessed one year after adolescents’ high school graduation. This structuring of the data precludes the possibility that the obtained results might reflect reversed directions of causal influence, and therefore bolsters confidence in the substantive interpretation of the results.

Discussion

This research examined whether self-verification processes mediated self-fulfilling prophecy effects. We tested this hypothesis by examining how mothers’ false beliefs about their adolescents’ academic outcomes shaped their adolescents’ post-secondary educational attainment. We addressed this issue with data obtained from mothers and their adolescent children across six years of adolescence. Results supported the hypothesis that self-verification processes mediated mothers’ self-fulfilling effects on their adolescents’ educational attainment. There was a significant indirect effect of mothers’ beliefs on their adolescents’ educational attainment through adolescents’ educational aspirations. Before discussing the importance of this finding, we first address issues surrounding the interpretation of findings from correlational designs and the relevance of these issues to the current research.

Interpreting Correlational Data

Using a correlational design to test for self-fulfilling prophecies has several advantages. It enables researchers to test whether self-fulfilling prophecies have negative influences on important target outcomes, such as academic performance and drug use, which would be unethical to examine with an experimental design. It also enables researchers to assess the extent to which perceivers shape targets’ outcomes through self-fulfilling prophecies within the naturalistic environment which is typically characterized by high levels of perceiver accuracy (Madon et al., 2001). Nonetheless, correlational designs do not provide as strong a basis for inferring causal relationships as do experimental designs. With a correlational design one cannot determine whether the predictor caused the dependent variable, the dependent variable caused the predictor, or whether both were caused by an unmeasured third variable. However, a longitudinal design – such as that used herein – does enable one to rule out the possibility that the dependent variable exerted a causal influence upon the predictor because measurement of the predictor is temporally antecedent to changes in the dependent variable.

The potential omission of a relevant background predictor variable is a limitation that characterizes all correlational research. No matter how many controls are included in an analytic model, it is always possible that a relevant one was omitted. The potential omission of a relevant background predictor variable represents an accuracy alternative to our self-fulfilling prophecy explanation because it raises the possibility that mothers based their beliefs about their adolescents’ academic outcomes on a valid predictor of educational attainment that was not included in the analytic models. If this occurred, then mothers’ beliefs about their adolescents were more accurate than estimated, and their self-fulfilling effects were smaller than reported. Although it is not possible to entirely rule out accuracy as an alternative explanation for our findings, there are a number of reasons why we believe that a self-fulfilling prophecy interpretation is more plausible.

First, a self-fulfilling prophecy interpretation is consistent with a long history of experimental findings showing that perceivers’ inaccurate beliefs can shape targets’ behaviors via self-fulfilling prophecies (see Snyder, 1984, 1992; Snyder & Stukas, 1999, for reviews). Of course, just because experiments find self-fulfilling prophecies does not prove that the mothers in our sample had self-fulfilling effects on their adolescents’ educational attainment. Nonetheless, confidence in the validity of a general conclusion increases when naturalistic and experimental investigations offer analogous results. Related to this, the findings we obtained in this study correspond to those that we previously obtained with respect to adolescents’ substance use (Madon et al., 2008).

Second, to reduce the likelihood that our findings reflected accuracy rather than self-fulfilling influence, we included a large number of controls – more controls, in fact, than any other study examining the self-fulfilling effect of perceivers’ beliefs on adolescents’ academic outcomes (see Jussim & Eccles, 1995, for a review). Rarely have studies controlled for both students’ grades and standardized test scores plus students’ motivation (see Jussim, 1989; Jussim & Eccles, 1992; Madon, Jussim, & Eccles, 1997 for exceptions) and no studies have controlled for adolescents’ deviant behaviors, perceptions of friends’ views about school, and adolescents’ ability to resist negative peer influences. The extensive controls that were used reduced the likelihood that an unmeasured variable produced the observed relations between mothers’ beliefs and adolescents’ educational attainment.

Third, we only interpreted the data as indicating the mediation of self-fulfilling prophecies to the extent that mothers’ beliefs had an indirect effect on the outcome of adolescents’ educational attainment through the mediator of adolescents’ educational aspirations. Thus, if a relevant background predictor had been omitted from the analyses, to the degree that it correlated with mothers’ beliefs, the accuracy-based portion of the relation between mothers’ beliefs and adolescents’ educational attainment would have been captured entirely by the direct effect between these variables (i.e., Path c; Jussim, 1991).

Nonetheless, the possibility that our analytic model omitted a variable that both correlated with mothers’ beliefs and had a causal effect on the mediational process we tested still exists. If this were the case, the self-fulfilling effect mothers had on their adolescents’ educational attainment would have been smaller than suggested because the influence that their beliefs had on the mediational process would have been overestimated. Although we cannot rule out this possibility, the convergence of our findings with those from the experimental literature as well as our own past results (Madon et al., 2008), combined with comprehensive set of relevant background predictors included in the analyses, lead us to conclude that the relations we observed reflect the occurrence of self-fulfilling prophecies. Accordingly, we next discuss the implications of our findings.

Mediational Processes of Self-Fulfilling Effects

A large body of research addressing self-fulfilling prophecies has focused on the behaviors through which perceivers transmit their beliefs to targets (see Brophy, 1983; Harris & Rosenthal, 1985; Rosenthal, 1973, for reviews). This literature has advanced the field by virtue of delineating specific behaviors and broad dimensions of behavior that operate as mediators of perceivers’ self-fulfilling effects. However, little attention has been paid to broad social psychological processes that may mediate self-fulfilling prophecy effects (see Madon et al., 2008 for an exception). To address this issue, we examined whether self-verification processes mediated self-fulfilling prophecy effects within a context that has not previously been examined –i.e., among mothers and their adolescent children in which adolescents’ educational attainment was the outcome variable.

Consistent with this process, mothers’ beliefs had a significant indirect effect on adolescents’ educational attainment through adolescents’ educational aspirations. This finding supports prior theorizing about the self-fulfilling prophecy process by providing evidence consistent with the interpretation that adolescents internalized their mothers’ false beliefs about them and then verified those internalized beliefs through their subsequent educational attainment. Therefore, this finding lends additional support to the idea that across a variety of dyadic relations, settings, and outcomes, targets internalize others’ false beliefs about them which they then self-verify through their subsequent behaviors. Moreover, the fact that we observed this pattern across six years suggests that the tendency for self-verification processes to mediate self-fulfilling prophecies may produce long-lasting changes in targets’ behavior.

Magnitude and Importance of Effects

Even though we found evidence that mothers had self-fulfilling effects on their adolescents’ educational attainment via adolescents’ educational aspirations, the magnitude of the effect was small. One way to understand the magnitude of the effect is to examine the standardized coefficient that corresponds to it. In terms of this metric, the magnitude of mothers’ self-fulfilling effects corresponded to an effect size of .33. Similarly, the proportion of mothers’ self-fulfilling effects that was mediated by self-verification processes corresponded to an effect size of .13 (Table 2). This latter value indicates that self-verification processes mediated 40% of mothers’ total self-fulfilling effects on adolescents’ educational attainment (i.e., .13/.33 = .40).

Although the self-fulfilling effects we observed were small, that does not mean they were unimportant. Whereas the vast majority of research examining naturally-occurring self-fulfilling prophecies has emphasized the important influence of teachers’ beliefs on students’ educational outcomes, our findings provide evidence that mothers’ beliefs produce similar self-fulfilling effects on their adolescents’ educational attainment. Our findings also highlight the important socializing influences that parents have on their adolescents’ future outcomes (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996). Indeed, these self-fulfilling effects emerged during a developmental period in which peers become an important source of influence (Berndt, 1979; Newcomb, & Bagwell, 1995; Wentzel, & Caldwell, 1997). Related to this, our findings suggest that one reason parents continue to have this socializing influence is because they shape how their adolescents come to view themselves.

Finally, even small self-fulfilling prophecy effects are important given evidence that they can become powerful via accumulation over time (Madon et al., 2006) and across perceivers (Madon et al., 2004). When self-fulfilling effects accumulate, a larger total self-fulfilling effect is created, thereby providing more opportunity for any process to mediate it. With respect to the current findings, this means that as mothers’ total self-fulfilling effects become larger through accumulation, there is more of a self-fulfilling prophecy effect for self-verification processes to mediate. This is true even if the degree to which self-verification processes remains stable, because mediating 40% of a large effect is objectively greater than mediating 40% of a small effect.

Conclusion

Psychological theory has long proposed that people construct social reality through the process of a self-fulfilling prophecy and a large body of research has been devoted to understanding mediators of this effect. Most of this research has focused on behavioral mediators that operate in a particular context, such as the behaviors that mediate the self-fulfilling effects of teachers’ beliefs on students’ achievement outcomes (Brophy, 1983; Harris & Rosenthal, 1985; Rosenthal, 1973). Although this focus has led to important insights that are relevant to targets’ outcomes in specific contexts, theorists have lamented the limited attention devoted to uncovering general processes of mediation that may operate across contexts (Harris, 1993; Harris & Rosenthal, 1985; Linehan, 1997). In an effort to redress this limitation, the current research addressed the potential generality of self-verification as a mediational process of self-fulfilling prophecies. Consistent with such a process, we found that mothers’ false beliefs (assessed while adolescents were in the 7th grade) had an indirect effect on their adolescents’ subsequent educational attainment (assessed one year after the adolescents had graduated from high school) via adolescents’ educational aspirations (assessed while they were in the 11th and 12th grades). The tendency for adolescents’ educational aspirations to mediate their mothers’ self-fulfilling effects highlights the important and long-lasting effect that self-views can have on important target outcomes across contexts (for a review, see Swann et al., 2007), and supports a long history of theorizing within the social sciences according to which the processes of self-verification and self-fulfilling prophecies may work in concert to produce these enduring effects (e.g., Brophy, 1983; Darley & Fazio, 1980; Eccles, et al., 1983; Madon, et al., 2008; McNulty & Swann, 1994; Snyder, 1984).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grants AA014702-13 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and DA 010815 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse awarded to Richard Spoth.

Appendix

Items Assessing Parental Involvement in Adolescents’ School-Related Activities. Reverse-score items are indicated by (R)

“Please tell me about how often you and this child have talked about his/her schoolwork.” (1 = Everyday; 6 = Never). (R)

“How many school events or functions put on by this child’s school do you attend?” (1 All of them; 5 None of them). (R)

“During the past month, how often did you do any of the following activities with your child in the study? How often did you and this child talk about whats going on at school?” (1 = Often; 4 = Never). (R)

“During the past month, how often did you do any of the following activities with your child in the study? How often did you and this child work on homework or a school project together?” (1 = Often; 4 = Never). (R)

“How true of you are these statements? If my child were in music, sports or other events at school, I would go see him or her.” (1 = Never true; 5 = Always true)

“How often do you contact someone at this child’s school about his/her progress?” (1 = Less than two or three times a year; 5 = Several times a month)

“These questions are about family rules. Since families have different rules, there are no right or wrong answers. Please read each statement below. Rate each statement according to how frequently it is true. In the evening, I ask my child if he/she has finished his/her homework.” (1 = Almost always true; 5 Almost always false). (R)

Footnotes

Omitted from our discussion is a study by Fazio, Effrein, and Falender (1981) that examined how differential treatment influenced targets’ self-perceptions. However, because Fazio et al. did not expose targets to perceivers’ false beliefs, this research precluded a self-fulfilling prophecy from occurring and, therefore, did not provide a clear test of the process under investigation.

Analyses that separately examined adolescents’ 11th grade and 12th grade educational aspirations as mediators did not change the results in terms of significance or pattern.

Data were obtained from the Capable Families and Youth study, a large intervention trial in which school districts were assigned to either a control condition or to one of two intervention conditions, the latter of which were designed to prevent adolescent substance use and other problem behaviors. The conditions were the Life Skills Training Program (LST-only), LST in combination with the Strengthening Families Program for parents and youth aged 10–14 (LST + SFP10-14), and a minimal contact control condition. Accordingly, analyses of the current study included and statistically controlled for the intervention condition, though corresponding results are not reported. Readers interested in the Capable Families intervention conditions and their effects are referred to the work cited by Spoth and colleagues provided online at http://www.ppsi.iastate.edu/.

References

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR. Achievement in the first 2 years of school: Patterns and processes. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1988;53:1–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. Developmental changes in conformity to peers and parents. Developmental Psychology. 1979;15:606–616. [Google Scholar]

- Bleeker MM, Jacobs JE. Achievement in math and science: Do mothers’ beliefs matter 12 years later? Journal of Educational Psychology. 2004;96:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy JE. Research on the self-fulfilling prophecy and teacher expectations. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1983;75:631–661. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran WG. Sampling techniques. 3. New York: John Wiley; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM, Findley M, Good T. Relations between student achievement and various indexes of teacher expectations. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1982;74:577–579. [Google Scholar]

- Darley JM, Fazio RH. Expectancy confirmation processes arising in the social interaction sequence. American Psychologist. 1980;35:867–881. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle WJ, Hancock G, Kifer E. Teachers’ perceptions: Do they make a difference? Journal of the Association for the Study of Perception. 1972;7:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Jacobs J, Harold J, Yoon K, Amerbach A, Freedman Doan C. Expectancy effects are alive and well on the home front: Influences on, and consequences of parents’ beliefs regarding their daughters’ and sons’ abilities and interests. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association; San Francisco, CA. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles-Parsons JS, Adler TF, Futterman R, Fogg SB, Kaczala CM, Meece JL, Midgley C. Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In: Spence JT, editor. Achievement and achievement motivation. San Francisco, CA: Freeman; 1983. pp. 75–146. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles-Parsons J, Adler TF, Kaczala CM. Socialization of achievement attitudes and beliefs: Parental influences. Child Development. 1982;53:310–321. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle DR, Alexander KL, Olson LS. First grade and educational attainment by age 22: A new story. American Journal of Sociology. 2005;110:1458–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle DR, Hayduk LA. Early schooling: Cognitive and affective outcomes. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle DR, Webster M., Jr Raising children’s performance expectation. Social Sciences Research. 1972;1:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio R, Effrein EA, Falender VJ. Self-perceptions following social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1981;41:332–342. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MJ. Issues in studying the mediation of expectancy effects: A taxonomy of expectancy situations. In: Blanck PD, editor. Interpersonal expectations: Theory, research, and applications. London: Cambridge University Press; 1993. pp. 350–378. [Google Scholar]

- Harris MJ, Rosenthal R. Mediation of interpersonal expectancy effects: 31 meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;97:363–386. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JE, Chin CS, Bleeker MM. Enduring Links: Parents’ expectations and their young adult children’s gender-typed occupational choices. Educational Research and Evaluation. 2006;12:395–407. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L. Self-fulfilling prophecies: A theoretical and integrative review. Psychological Review. 1986;93:429–445. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L. Teacher expectations: Self-fulfilling prophecies, perceptual biases, and accuracy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:469–480. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L. Social perception and social reality: A reflection-construction model. Psychological Review. 1991;98:54–73. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L, Eccles JS. Teacher expectations II: Construction and reflection of student achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:947–961. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L, Eccles J. Naturally occurring interpersonal expectancies. Review of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;15:74–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kreft I, de Leeuw J. Introducing statistical methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. Introducing multilevel modeling. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Self-verification and drug-abusers: Implications for treatment. Psychological Science. 1997;8:181–183. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Guyll M, Buller AA, Scherr KC, Willard J, Spoth D. The mediation of mothers’ self-fulfilling effects on their children’s alcohol use: Self-verification, informational conformity, and modeling processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95:369–384. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.2.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Guyll M, Spoth RL. The self-fulfilling prophecy as in intra-family dynamic. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:459–469. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Guyll M, Spoth RL, Cross SE, Hilbert SJ. The self-fulfilling influence of mother expectations on children’s underage drinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1188–1205. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Guyll M, Spoth RL, Willard J. Self-fulfilling prophecies: The synergistic accumulation of parents’ beliefs on children’s drinking behavior. Psychological Science. 2004;15:837–845. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Jussim L, Eccles JS. In search of the powerful self-fulfilling prophecy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:791–809. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.4.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Jussim L, Keiper S, Eccles J, Smith A, Palumbo P. The accuracy and power of sex, social class, and ethnic stereotypes: A naturalistic study in person perception. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24:1304–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Smith A, Jussim L, Russell DW, Eccles JS, Palumbo P, Walkiewicz M. Am I as you see me or do you see me as I am? Self-fulfilling prophecies and self-verification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:1214–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Willard J, Guyll M, Trudeau L, Spoth R. Self-fulfilling prophecy effects on mothers’ beliefs on children’s alcohol use: Accumulation, dissipation, and stability over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:911–926. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.6.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Cozzarelli C, Testa M, McFarlin DB. Self-verification versus expectancy confirmation in social interaction: The impact of self-focus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1988;14:346–359. doi: 10.1177/0146167288142012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marjoribanks KM. Relationship of children’s ethnicity, gender, and social status to their family environments and school-related outcomes. The Journal of Social Psychology. 1991;131:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Marjoribanks KM. Family background, academic achievement, and educational aspirations as predictors of Australian young adults’ educational attainment. Psychological Reports. 2005;96:751–754. doi: 10.2466/pr0.96.3.751-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. The self-fulfilling prophecy. Antioch Review. 1948;8:193–210. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty SE, Swann WB. Identity negotiation in roommate relationships: The self as architect and consequence of social reality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:1012–1023. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb AF, Bagwell CL. Children’s friendship relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:306–347. [Google Scholar]

- Palardy MJ. What teachers believe-what children achieve. The Elementary School Journal. 1969;69:370–374. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavioral Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rist RC. Student social class and teacher expectations: The self-fulfilling prophecy in ghetto education. Harvard Education Review. 1970;40:411–451. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. On the social psychology of the self-fulfilling prophecy: Further evidence for Pygmalion effects and their mediating mechanisms. New York, NY: MSS Modular Publications; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Seaver WB. Effects of naturally induced teacher expectancies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1973;28:333–342. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Jussim L, Eccles JS. Do self-fulfilling prophecies accumulate, dissipate, or remain stable over time? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:548–565. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.3.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Jussim L, Eccles JS, VanNoy M, Madon S, Palumbo P. Self-fulfilling prophecies, perceptual biases, and accuracy at the individual and group levels. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1998;34:530–561. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder M. When belief creates reality. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental psychology. Vol. 18. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1984. pp. 247–305. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder M. Motivational foundations of behavioral confirmation. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 25. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1992. pp. 67–114. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder M, Stukas AA., Jr Interpersonal processes: The interplay of cognitive, motivational, and behavioral activities in social interaction. Annual Review of Psychology. 1999;50:273–303. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder M, Swann WB., Jr Behavioral confirmation in social interaction: From social perception to social reality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1978;14:148–162. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Randall KG, Shin C. Increasing school success through partnership-based family competency training: Experimental study of long-term outcomes. School Psychology Quarterly. 2008;23:70–89. doi: 10.1037/1045-3830.23.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Trudeau L, Shin C. Longitudinal substance initiation outcomes for a universal preventive intervention combining family and school programs. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:129–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland A, Goldschmid ML. Negative teacher expectation and IQ change in children with superior intellectual potential. Child Development. 1974;45:853–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB., Jr Identity negotiation: Where two roads meet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:1038–1051. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB, Jr, Chang-Schneider C, Larsen McClarty K. Do people’s self-views matter? Self-concept and self-esteem in everyday life. American Psychologist. 2007;62:84–94. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR, Caldwell K. Friendships, peer acceptance, and group membership: Relations to academic achievement in middle school. Child development. 1997;68:1198–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West CK, Anderson TH. The question of preponderant causation in teacher expectancy research. Review of Educational Research. 1976;46:613–630. [Google Scholar]

- Willard J, Madon S, Guyll M, Spoth R, Jussim L. Self-efficacy as a moderator of negative and positive self-fulfilling prophecy effects: Mothers’ beliefs and children’s alcohol use. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;38:499–520. [Google Scholar]

- Williams T. Teacher prophecies and the inheritance of inequality. Sociology of Education. 1976;49:223–236. [Google Scholar]