Abstract

AIM: To investigate the efficacy of amitriptyline with proton pump inhibitor (PPI) for the treatment of functional chest pain (FCP).

METHODS: This was a randomized, open-label trial investigating the addition of low dose amitriptyline (10 mg at bedtime) to a conventional dose of rabeprazole (20 mg/d) (group A, n = 20) vs a double-dose of rabeprazole (20 mg twice daily) (group B, n = 20) for patients with FCP whose symptoms were refractory to PPI. The primary efficacy endpoints were assessed by global symptom score assessment and the total number of individuals with > 50% improvement in their symptom score.

RESULTS: The between-group difference in global symptom scores was statistically significant during the last week of treatment (overall mean difference; 3.75 ± 0.31 vs 4.35 ± 0.29, the between-group difference; P < 0.001). Furthermore, 70.6% of patients in group A had their symptoms improve by > 50%, whereas only 26.3% of patients in group B had a similar treatment response (70.6% vs 26.3%, P = 0.008). Specifically, patients in group A had a significantly greater improvement in the domains of body pain and general health perception than did patients in group B (52.37 ± 17.00 vs 41.32 ± 12.34, P = 0.031 and 47.95 ± 18.58 vs 31.84 ± 16.84, P = 0.01, respectively).

CONCLUSION: Adding amitriptyline to a PPI was more effective than a double-dose of PPI in patients with FCP refractory to a conventional dose of PPI.

Keywords: Functional chest pain, Proton pump inhibitor, Amitriptyline

Core tip: Hypersensitivity and psychological problems have an important role in the pathogenesis of functional chest pain (FCP). In this regard, the principal treatment of FCP has moved towards hypersensitivity modulation and antidepressant agents on the basis that the underlying mechanisms were increased pain perception or visceral hyperalgesia in addition to psychologic causes. This is the first study to report that adding low-dose amitriptyline to a conventional dose of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is more effective than a double-dose of PPI in patients with FCP resistant to a conventional dose of PPI treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Noncardiac chest pain (NCCP) is a common condition that affects up to one third of the general population. Moreover, the effect of NCCP on an individual’s quality of life and use of health care resources is considerable because evaluation of new patients with NCCP may require a variety of costly tests. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common cause of NCCP and is present in up to 60% of patients with NCCP in Western countries[1]. In addition, some patients with NCCP are regarded as having functional chest pain (FCP) by Rome III criteria[2-4].

Despite extensive evidence indicating that the causes of FCP are visceral hypersensitivity and psychiatric pathology[5], the underlying mechanism for FCP has not been fully understood. This problem makes the treatment of FCP quite difficult. Indeed, therapeutic gains with a conventional dose of empirical PPI treatment may be obtained in only 9%-39% of patients with FCP[6,7]. A Cochrane review suggests that doubling the PPI dose is associated with greater relief of symptoms for those with NCCP. However, there is no clear PPI dose-response relationship for symptom resolution[8].

Reflecting recent interest, several authors have confirmed an important role for hypersensitivity in the pathogenesis of FCP[9,10]. Furthermore, psychological evaluation of patients with FCP has been suggested because a significant proportion may meet the criteria for panic disorder and depressive symptoms[11,12]. In this regard, several studies have assessed the psychological treatment of FCP with tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin-norepinephine reuptake inhibitors[11,13,14]. Hence, the principal treatment of FCP has moved towards hypersensitivity modulation and antidepressant agents on the basis that the underlying mechanisms are increased pain perception or visceral hyperalgesia in addition to psychologic causes[15,16]. Consequently, it would be reasonable to assume a beneficial effect of amitriptyline (a TCA) on the symptoms of FCP. As mentioned earlier, these drugs could reduce the severity of psychological manifestations which are thought to exacerbate the symptoms of FCP. In addition, amitriptyline has central analgesic actions, in addition to local pharmacological actions on the upper gut which specifically alter transit and gastric accommodation[16,17]. Although widely used for FCP, the combined therapy of PPI and antidepressant agents is not evidence-based. The purpose of this study is to investigate whether adding low-dose amitriptyline to a conventional dose of PPI is more effective than a double-dose of PPI in patients with FCP resistant to conventional dose of PPI treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and study protocol

This was a single-center, prospective, randomized, open-label trial. Over 8 wk we investigated the addition of a subtherapeutic dose of amitriptyline to a conventional dose of PPI (group A) vs a double-dose of PPI (group B) for the treatment of refractory FCP. Consecutive patients were recruited for the study who presented to the Yonsei University Medical Center with persistent unexplained midline chest pain for a minimum of 3 mo, and who had a normal upper endoscopy, 24 h impedance esophageal pH monitoring, and esophageal manometry. Patients were only considered eligible for enrollment if they were free from cardiac, musculoskeletal, and pulmonary diseases, and if they had < 50% improvement of their global symptom scores after treatment with a conventional dose of PPI (rabeprazole 20 mg/d) for at least 1 mo. Patients were excluded if they had erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, other GERD-related disorders, or peptic ulcer disease during upper endoscopy. In addition, patients were excluded if they were unable to complete 24 h impedance esophageal pH monitoring or esophageal manometry, and if the results of these tests indicated GERD or a definite motility disorder. Finally, patients were excluded if they had a depressive disorder [Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score > 19] or if they refused all procedures of this study. After signing a written informed consent patients were asked to complete a baseline Short-Form (SF-36) to generate quality of life (QOL) data, a global symptom score, and a BDI score. Enrollees were randomized by an independent investigator using a computer-generated random number table to one of two groups, whereby those in group A were treated with the combination of amitriptyline (10 mg at bedtime) and rabeprazole (20 mg/d), and those in group B were treated with a double-dose of rabeprazole (20 mg twice daily).

Efficacy was assessed by patient evaluation of global symptom relief scores using a daily symptom diary each week. At each visit the symptom diary was checked, side effects were reported, and compliance was assessed. At the end of the 8 wk study patients were asked to complete a final QOL questionnaire, global symptom and BDI scores were generated, and any side effects were reported. Primary efficacy endpoints were assessed by the subjective global symptom relief score and the total number of individuals with > 50% improvement in their symptom score. Secondary endpoints were related to QOL indices and the BDI score. The study described in this report was approved by the ethics committee of Yonsei University School of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea.

Demographics

All subjects completed a demographic questionnaire including age, gender, residence area, smoking and alcohol history, and body mass index (BMI).

Symptom assessment

The overall clinical assessment (global symptom score) was made using an analogue scale ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 10 (intolerable), carried out immediately before treatment[18]. All patients were also questioned regarding symptoms possibly related to complications of the treatment. Subsequently, patients were contacted every week and re-evaluated for the presence of clinical symptoms. In addition, patients were asked to report to the center if any additional symptoms occurred during the study period. In both study groups the treatment of FCP was considered effective if the global symptom score improvement was > 50%[19].

SF-36

Health-related QOL was assessed with the SF-36, which contains 36 items that, when scored, yield eight domains. This approach was chosen because of its reliability and validity among both diseased and general populations, and given its usefulness in comparing the health burden of different conditions and the benefits of treatment. Specifically, the physical functioning domain (10 items) assesses limitations of physical activities, such as walking and climbing stairs. The physical role (4 items) and emotional role (3 items) domains measure problems with work or other daily activities as a result of physical health or emotional problems. The body pain domain (2 items) assesses limitations due to pain, and the vitality domain (4 items) measures energy and tiredness. The social functioning domain (2 items) examines the effect of physical and emotional health on normal social activities, and the mental health domain (5 items) assesses happiness, nervousness, and depression. Finally, the general health perception domain (5 items) evaluates personal health and the expectation of changes in health. All domains were scored on a scale from 0 to 100, with 100 representing the best possible health state.

Depression

We assessed depression using the BDI instrument. The BDI is a self-administered 21-item self-reported scale measuring supposed manifestations of depression. In particular, a BDI score between 9 and 18 implies mild-to-moderate depression, a score between 19 and 30 signifies moderate-to-severe depression, and a score > 30 implies severe depression. This score was measured before and after treatment.

Statistical analysis

On the basis of a previous meta-analysis with antidepressants[20], a two-sided comparison of the primary outcome variable with 17 patients per group, at the end of the treatment period, had the required 90% power and 5% type I error rate to detect a difference of 40% between the groups receiving additional amitriptyline and high dose PPI in the number of patients reporting > 50% improvement in symptoms (MedCalc® Version 12.3; MedCalc Software: Mariarkerke, Belgium). To allow for possible dropouts, defined as patients who failed to present or failed to follow the medication instructions, 20 subjects were required for each group.

To account for missing data, analysis of the primary and secondary endpoints was performed according to intention to treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses. Descriptive statistics were provided for the binary and continuous variables using the incidence frequency (%) and the mean (standard distribution). The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare binary variables, and the two sample t test was used to compare continuous variables. Between-group differences of global symptom scores over time were analyzed using a linear mixed model with an unstructured residual covariance matrix. There were also two fixed effects that were assessed, including a between-subjects treatment effect (group A: amitriptyline + rabeprazole, group B: double dose of rabeprazole) and a within-subject time effect (time: week 0 to week 8). A possible group difference across time was analyzed by the group and time interaction effect. We also evaluated treatment effects of the drug on each SF-36 domain measured at baseline and during follow-up using a two sample t test. Two-sided P values were calculated with significance accepted at the 5% level. When necessary, the P value was adjusted by Bonferroni correction for multiple pair-wise comparisons. We primarily report the outcomes evaluated by ITT analysis since there were no differences for test results between ITT and PP analyses. All of the statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Figure 1 shows the progress of patients throughout the study. A total of 73 patients were enrolled in the study, all of whom had persistent unexplained midline chest pain for a minimum of 3 mo, a normal upper endoscopy, 24 h impedance esophageal pH monitoring, and esophageal manometry, and an improvement of their global symptom score by < 0% after treatment with a conventional dose of PPI (rabeprazole 20 mg/d) for at least 1 mo. The random assignment of patients into two arms resulted in 20 patients in group A designated to receive the addition of amitriptyline 10 mg once daily to rabeprazole 20 mg/d, and 20 patients in group B designated to receive a rabeprazole dose of 20 mg twice daily. Overall, 4 patients dropped out of the study, including three patients because of mild medication side effects (all of whom belonged to group A) and one who was lost to follow-up (this patient belonged to group B). Of the 36 patients who completed the 8-wk trial 17 were assigned to group A and 19 to group B. The ITT population consisted of 40 patients.

Figure 1.

Flow of patients throughout the trial. 1Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease (n = 5), and peptic ulcer disease (n = 1). Pathological acid exposure was found in four patients by ambulatory 24 h esophageal pH monitoring. An esophageal motility disorder was found in one patient by esophageal manometric examination. The Beck Depression Index score of one patient exceeded 19 points; 2Sixteen patients refused to take part in this study, and five patients refused examination by esophageal manometry or ambulatory 24 h esophageal pH monitoring; 3Out of 4 patients, three in group A withdrew because of an amitriptyline-associated adverse event. One patient in group B dropped out of the trial because of loss to follow-up. BDI: Beck Depression Inventory.

Baseline characteristics for each treatment group in the ITT population are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of individuals in group A was 51.1 ± 8.5 years vs 49.7 ± 9.59 years for those in group B. There was a slight female predominance in both groups: 55% in group A and 60% in group B. Of those in groups A and B respectively, 15% vs 20% used alcohol and 20% vs 45% smoked cigarettes. The mean BMI was 21.56 ± 1.74 for subjects in group A and 21.79 ± 2.2 in group B. There were no significant differences between group A and group B regarding symptom index, acid exposure time, and baseline BDI, indicating adequate randomization. Furthermore, subjects in both treatment groups of the ITT population showed generally similar values for most laboratory test results.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the intention to treat population

| Variables |

Group |

P value | |

| A (n = 20) | B (n = 20) | ||

| Age (yr) | 51.1 ± 8.5 | 49.7 ± 9.59 | 0.628 |

| Gender (female) | 11 (55) | 12 (60) | 0.749 |

| Alcohol | 3 (15) | 4 (20) | 0.677 |

| Smoking | 4 (20) | 9 (45) | 0.091 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.56 ± 1.74 | 21.79 ± 2.2 | 0.716 |

| Region (rural) | 9 (52.94) | 7 (36.84) | 0.332 |

| Symptom index1 | 5 (25) | 5 (25) | - |

| Acid exposure time | 0.52% ± 0.68% | 0.44% ± 0.8% | 0.719 |

| Baseline BDI | 6.9 ± 2.22 | 7.35 ± 1.93 | 0.498 |

Data are expressed as absolute numbers (percentage) or mean ± SD.

Symptom index indicated number of patients who has score of symptom index by > 50% on 24-h esophageal pH monitoring. BMI: Body mass index; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory.

Global symptom score assessment

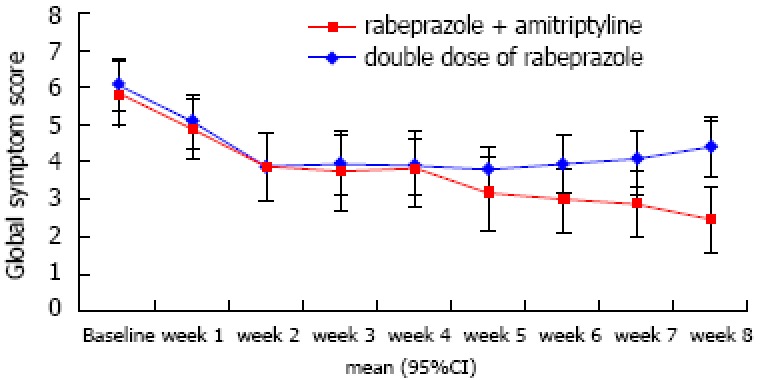

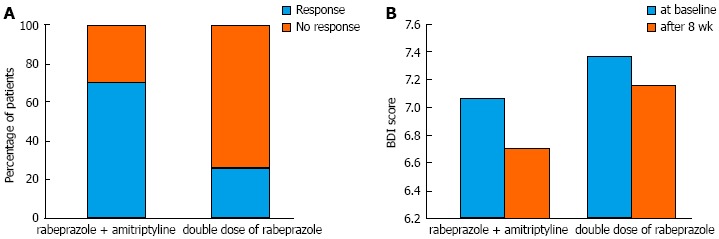

The global symptom scores over time associated with each treatment are shown in Figure 2. The overall mean difference between the two groups was not significantly different (3.75 ± 0.31 vs 4.35 ± 0.29, P = 0.172). However, we found that the time effect and time × group interaction effect were significant (P < 0.001 and P = 0.006, respectively). For instance, the global symptom scores significantly declined in group A. For group B, however, the global symptom scores decreased until week 2 and then somewhat increased after week 5 until the end of study follow-up (Table 2). Consequently, the between-group difference in global symptom scores was statistically significant at the last week (P < 0.001). Figure 3A shows the response rates in patients with FCP treated with amitriptyline and rabeprazole vs the double-dose of rabeprazole on the PP analysis. We found that 70.6% of amitriptyline and rabeprazole-treated patients showed improvement by > 50%, and that 29.4% failed to respond, given a response of < 50%. On the contrary, only 26.3% of patients showed a response to a double-dose of rabeprazole. This difference was significant (χ2 = 7.06, df = 1, P = 0.008).

Figure 2.

Efficacy of both treatment groups on the global symptom score. The global symptom scores over time was associated with each treatment. The overall mean difference between the two groups was not significantly different (P = 0.172). However, we found that the time effect and time × group interaction effect were significant (P < 0.001 and P = 0.006, respectively). Consequently, the between-group difference in global symptom scores was statistically significant at the last week (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Global symptom scores by follow-up time

| Time | Group A | Group B | P value1 |

| Week 0 | 5.85 (5.09-6.61) | 6.10 (5.34-6.86) | 0.642 |

| Week 1 | 4.90 (4.14-5.66) | 5.10 (4.34-5.86) | 0.709 |

| Week 2 | 3.94 (3.08-4.80) | 3.90 (3.06-4.74) | 0.948 |

| Week 3 | 3.76 (2.86-4.66) | 3.95 (3.10-4.80) | 0.755 |

| Week 4 | 3.82 (2.96-4.68) | 3.90 (3.10-4.70) | 0.889 |

| Week 5 | 3.18 (2.38-3.98) | 3.80 (3.05-4.55) | 0.259 |

| Week 6 | 3.00 (2.21-3.79) | 3.95 (3.21-4.69) | 0.084 |

| Week 7 | 2.89 (2.12-3.65) | 4.05 (3.33-4.77) | 0.031 |

| Week 8 | 2.47 (1.68-3.27) | 4.37 (3.63-5.11) | 0.001 |

Data are least square means (95%CI). Group A: rabeprazole + amitriptyline group vs Group B: double dose of proton pump inhibitor group.

P value < 0.006 is considered statistically significant after adjusting the significance level of 0.05 using Bonferroni correction method for multiple comparisons. The significant difference between two groups was found at week 8 only (P < 0.006).

Figure 3.

Symptom response rate (A) and Beck Depression Inventory scores (B) after treatment. A: The response rates in patients after treatment with rabeprazole + amitriptyline vs double-dose of rabeprazole on the per-protocol analysis are demonstrated. In this analysis, the difference of the response rate between both groups was statistically significant; B: The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores after treatment with amitriptyline and rabeprazole vs double-dose of rabeprazole are represented. The overall mean difference of BDI scores after 8 wk of treatment was not significantly different between group A and group B (6.71 ± 1.99 vs 7.16 ± 1.89, respectively; P = 0.49).

Health-related QOL assessment

Table 3 shows the health-related QOL as assessed by the SF-36 before and after treatment. There were no statistically significant differences between the two patient groups at baseline in any of the eight SF-36 domains. Moreover, the treatment effect at the end of the study was not significantly different between most domains of the SF-36, except for the body pain and general health perception factors. Patients who received amitriptyline and rabeprazole treatment had a significantly greater improvement in the domains of body pain and general health perception than those who received a double-dose of rabeprazole treatment (P = 0.031 and 0.01, respectively). The majority of the other domains of the SF-36 did not reach statistical significance.

Table 3.

Treatment effect on the health-related quality of life assessed with Short-Form 36

| SF-36 score |

Group |

P value | |

| Group A (n = 20) | Group B (n = 20) | ||

| Physical functioning | |||

| Baseline | 42.01 ± 13.47 | 32.83 ± 17.06 | 0.211 |

| End of treatment | 37.28 ± 12.76 | 38.42 ± 7.83 | 0.753 |

| Role -physical | |||

| Baseline | 31.51 ± 14.9 | 29.45 ± 15.51 | 0.670 |

| End of treatment | 37.88 ± 10.16 | 39.02 ± 12.49 | 0.768 |

| Role-emotional | |||

| Baseline | 32.01 ± 12.12 | 38.39 ± 12.68 | 0.112 |

| End of treatment | 36.99 ± 12.62 | 30.14 ± 16.95 | 0.182 |

| Social functioning | |||

| Baseline | 37.95 ± 14.06 | 33.82 ± 13.90 | 0.356 |

| End of treatment | 36.41 ± 13.03 | 30.07 ± 12.83 | 0.151 |

| Body pain | |||

| Baseline | 34.94 ± 14.39 | 30.13 ± 12.09 | 0.260 |

| End of treatment | 52.37 ± 17.00 | 41.32 ± 12.34 | 0.031 |

| General health perceptions | |||

| Baseline | 38.63 ± 11.66 | 31.82 ± 12.94 | 0.088 |

| End of treatment | 47.95 ± 18.58 | 31.84 ± 16.84 | 0.010 |

| Mental health | |||

| Baseline | 38.82 ± 14.72 | 39.20 ± 10.67 | 0.927 |

| End of treatment | 44.69 ± 10.79 | 38.88 ± 10.50 | 0.111 |

| Energy/vitality | |||

| Baseline | 38.08 ± 12.50 | 34.39 ± 12.64 | 0.360 |

| End of treatment | 42.95 ± 15.32 | 35.14 ± 10.87 | 0.084 |

All results are expressed as mean ± SD. Group A received amitriptyline and rabeprazole and group B received double dose of rabeprazole. P values are for the comparison of amitriptyline and rabeprazole vs double dose of rabeprazole at baseline and end of the treatment. Patients who received amitriptyline and rabeprazole treatment had a significantly greater improvement in the domains of body pain and general health perception than those who received a double dose of rabeprazole treatment (P = 0.031 and P = 0.01, respectively). The majority of the other domains of the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) did not reach statistical significance.

Depression

The overall mean difference of BDI at baseline and after the 8-wk treatment period was not significantly different between group A and group B (6.9 ± 2.22 vs 7.35 ± 1.93, P = 0.498, and 6.71 ± 1.99 vs 7.16 ± 1.89, P = 0.49, respectively). There was no significant difference in the depression score from baseline to the end of treatment in the double dose of PPI treatment group (P = 0.3). In the group receiving rabeprazole and amitriptyline, this result was marginally significant (P = 0.06). The change in value of the BDI scores associated with treatment is shown in Figure 3B.

Tolerability and safety assessment

Three patients withdrew from the study because of non life-threatening adverse events while receiving the combination of amitriptyline and rabeprazole (excessive sleeping, dizziness and general weakness).

DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this study was to determine the efficacy of low-dose amitriptyline with a conventional dose of PPI for the treatment of FCP with refractory symptoms to a conventional dose of PPI. We found favorable evidence for the efficacy of antidepressants in improving global symptom scores and health related QOL in patients with FCP refractory to conventional doses of PPIs. In other words, we found that adding low-dose amitriptyline to a conventional dose of PPI resulted in significantly decreased symptoms compared with a double-dose of PPI, with minimal side effects. Interestingly, this outcome is very similar to the open-label response to antidepressants seen with irritable bowel syndrome[21].

Anti-reflux therapy with PPIs plays an important role in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with NCCP because the major cause of NCCP is GERD, and since the management of NCCP is largely empirical[22,23]. However, in patients with non GERD-related NCCP (especially those refractory to conventional doses of PPI), treatment should be targeted to alternative drugs, such as pain modulating agents[24]. Indeed, therapeutic gains with PPI treatment have been obtained in only 9%-39% of non GERD-related NCCP patients[6,22,25]. Recent studies have focused on modulating nociception and visceral pain sensation pathways for decreasing chest pain using antidepressants[11,26]. For these reasons, it would be reasonable to assume a beneficial effect of antidepressant drugs, such as TCAs, on the symptoms of FCP. In fact, to investigate the efficacy of antidepressant treatments for FCP, one meta-analysis of seven studies and 319 participants indicated that there was strong evidence for an association of antidepressants with a reduction in pain and psychological symptoms. However, the drugs assessed in this analysis were varied and included a TCA, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and a serotonin-norepinephine reuptake inhibitor[14]. Therefore, the possible effect of amitriptyline for FCP is unclear. Moreover, until now there has been no randomized controlled study to investigate the effects of combining TCAs with PPIs for the treatment of FCP refractory to conventional therapy.

The results of our clinical study suggest that FCP may respond favorably to low-dose amitriptyline in combination with a PPI. Eventually the symptomatic overlap with functional gastrointestinal disorders, the recognized association of functional dyspepsia with visceral hypersensitivity, and the response of several other functional gut disorders to TCAs may all hold clues to the seeming success in our patients. In our study, we used doses of amitriptyline far below those necessary for an antidepressant benefit. This likely explains the positive association of amitriptyline for reducing pain in the absence of a benefit for depressive symptoms. The synergistic effects of amitriptyline in combination with a conventional dose of PPI could have an important role in improving QOL of those with FCP. Because the therapeutic effects of amitriptyline are usually achieved within 4-6 wk, the duration of our trial was considered adequate for evaluating the efficacy of this drug. Our results show that an 8-wk treatment regimen with amitriptyline and rabeprazole significantly improved the global symptom score given the response rate of 70.6%, which was in comparison to the response rate for a double-dose of rabeprazole of only 26.3%. However, analysis of the SF-36 as a QOL measurement showed satisfactory efficacy in only two domains. This might have been caused by the small sample size, which may have been inadequate for detecting differences in secondary outcomes, although it was adequate for detecting the required difference in the primary outcome variable.

Our study has a few limitations. The open-label nature of this study could lead to some biases with generalization of the results. The sample size was also relatively small and further investigation based on a larger number of patients is necessary to corroborate our data. Finally, our study duration was relatively short. Indeed, the short duration of most studies and the lack of follow-up after treatment cessation leave the question unanswered whether antidepressants have long-term beneficial effects on FCP symptoms, as well as the optimal treatment duration. Nevertheless, this study is of value because it is the first study examining the efficacy of amitriptyline on patients with FCP with symptoms refractory to a conventional dose of PPI. We did not encounter major or unexpected side effects related to amitriptyline.

In conclusion, the combination of low-dose amitriptyline with a standard PPI regimen was more effective than a double-dose of PPIs in patients with FCP refractory to conventional PPI therapy, without serious adverse events. The safety profile and efficacy in the subjects using low-dose amitriptyline as well as the significant improvement in global symptom scores may justify the addition of amitriptyline for the treatment of refractory FCP.

COMMENTS

Background

Despite extensive evidence indicating that the causes of functional chest pain (FCP) are visceral hypersensitivity and psychiatric pathology, the underlying mechanism for FCP is largely unknown. This problem makes the treatment of FCP quite difficult.

Research frontiers

The principal treatment of FCP has moved towards hypersensitivity modulation and antidepressant agents on the basis that the underlying mechanisms were increased pain perception or visceral hyperalgesia in addition to psychologic causes. In this study, the authors demonstrate that amitriptyline, as a tricyclic antidepressant, would appear to have a beneficial effect on the symptoms of FCP.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Recent reports have highlighted the psychological treatment of FCP with tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin-norepinephine reuptake inhibitors. This is the first study to report that adding low-dose amitriptyline to a conventional dose of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is more effective than a double-dose of PPI in patients with FCP resistant to a conventional dose of PPI treatment.

Applications

The authors’ result demonstrates that the safety profile and efficacy in the subjects using low-dose amitriptyline as well as the significant improvement in global symptom scores may justify the addition of amitriptyline for the treatment of refractory FCP.

Terminology

FCP was defined as recurrent angina-like retrosternal chest pain with normal coronary anatomy and no detectable gastroenterological and respiratory causes after an adequate evaluation by Rome III criteria. The SF-36 as health-related quality of life contains 36 items that, when scored, yield eight domains. The BDI instrument as assessment for anxiety and depression is a self-administered 21-item self-reported scale measuring supposed manifestations of depression.

Peer review

The authors have focused on modulating nociception and visceral pain sensation pathways for decreasing chest pain using antidepressants. It revealed that the combination of low-dose amitriptyline with a standard PPI regimen was more effective than a double-dose of PPIs in patients with FCP refractory to conventional PPI therapy, without serious adverse events.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer Blonski W S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Ma S

References

- 1.Faybush EM, Fass R. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in noncardiac chest pain. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2004;33:41–54. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8553(03)00131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eslick GD, Jones MP, Talley NJ. Non-cardiac chest pain: prevalence, risk factors, impact and consulting--a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1115–1124. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kachintorn U. How do we define non-cardiac chest pain. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20 Suppl:S2–S5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richter JE. Chest pain and gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:S39–S41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarkar S, Aziz Q, Woolf CJ, Hobson AR, Thompson DG. Contribution of central sensitisation to the development of non-cardiac chest pain. Lancet. 2000;356:1154–1159. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02758-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickman R, Mattek N, Holub J, Peters D, Fass R. Prevalence of upper gastrointestinal tract findings in patients with noncardiac chest pain versus those with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)-related symptoms: results from a national endoscopic database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1173–1179. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Handel D, Fass R. The pathophysiology of non-cardiac chest pain. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20 Suppl:S6–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan M, Santana J, Donnellan C, Preston C, Moayyedi P. Medical treatments in the short term management of reflux oesophagitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD003244. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003244.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao SS, Hayek B, Summers RW. Functional chest pain of esophageal origin: hyperalgesia or motor dysfunction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2584–2589. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schey R, Villarreal A, Fass R. Noncardiac chest pain: current treatment. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2007;3:255–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cannon RO, Quyyumi AA, Mincemoyer R, Stine AM, Gracely RH, Smith WB, Geraci MF, Black BC, Uhde TW, Waclawiw MA. Imipramine in patients with chest pain despite normal coronary angiograms. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1411–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405193302003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung TK, Hou X, Lam KF, Chen J, Wong WM, Cha H, Xia HH, Chan AO, Tong TS, Leung GY, et al. Quality of life and psychological impact in patients with noncardiac chest pain. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:13–18. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181514725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee H, Kim JH, Min BH, Lee JH, Son HJ, Kim JJ, Rhee JC, Suh YJ, Kim S, Rhee PL. Efficacy of venlafaxine for symptomatic relief in young adult patients with functional chest pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1504–1512. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang W, Sun YH, Wang YY, Wang YT, Wang W, Li YQ, Wu SX. Treatment of functional chest pain with antidepressants: a meta-analysis. Pain Physician. 2012;15:E131–E142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao SS, Mudipalli RS, Remes-Troche JM, Utech CL, Zimmerman B. Theophylline improves esophageal chest pain--a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:930–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.North CS, Hong BA, Alpers DH. Relationship of functional gastrointestinal disorders and psychiatric disorders: implications for treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2020–2027. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i14.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talley NJ, Stanghellini V, Heading RC, Koch KL, Malagelada JR, Tytgat GN. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gut. 1999;45 Suppl 2:II37–II42. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasricha PJ, Ravich WJ, Hendrix TR, Sostre S, Jones B, Kalloo AN. Intrasphincteric botulinum toxin for the treatment of achalasia. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:774–778. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503233321203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fass R, Fennerty MB, Johnson C, Camargo L, Sampliner RE. Correlation of ambulatory 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring results with symptom improvement in patients with noncardiac chest pain due to gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:36–39. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199901000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen TM, Eslick GD. Systematic review: the treatment of noncardiac chest pain with antidepressants. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clouse RE, Lustman PJ, Geisman RA, Alpers DH. Antidepressant therapy in 138 patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a five-year clinical experience. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:409–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1994.tb00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong WM. Use of proton pump inhibitor as a diagnostic test in NCCP. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20 Suppl:S14–S17. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JH, Rhee PL. Recent advances in noncardiac chest pain in Korea. Gut Liver. 2012;6:1–9. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2012.6.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhee PL. Treatment of noncardiac chest pain. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20 Suppl:S18–S19. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang WH, Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Wong WM, Lam SK, Karlberg J, Xia HH, Fass R, Wong BC. Is proton pump inhibitor testing an effective approach to diagnose gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with noncardiac chest pain: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1222–1228. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.11.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuzawa-Yanagida K, Narita M, Nakajima M, Kuzumaki N, Niikura K, Nozaki H, Takagi T, Tamai E, Hareyama N, Terada M, et al. Usefulness of antidepressants for improving the neuropathic pain-like state and pain-induced anxiety through actions at different brain sites. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1952–1965. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]