Abstract

A deficiency in bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 (BMPR2) signaling is a central contributor in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). We have recently shown that endothelial-specific Bmpr2-deletion by a novel L1Cre line resulted in pulmonary hypertension. SMAD1 is one of the canonical signal transducers of the BMPR2 pathway, and its reduced activity has been shown to be associated with PAH. In order to determine whether SMAD1 is an important downstream mediator of BMPR2 signaling in the pathogenesis of PAH, we analyzed pulmonary hypertension phenotypes in Smad1-conditional knockout mice by deleting the Smad1 gene either in endothelial cells or in smooth muscle cells using L1Cre or Tagln-Cre mouse lines, respectively. A significant number of the L1Cre(+); Smad1 (14/35) and Tagln-Cre(+);Smad1 (4/33) mutant mice showed elevated pulmonary pressure, right ventricular hypertrophy and a thickening of pulmonary arterioles. A pulmonary EC line in which the Bmpr2 gene deletion can be induced by 4-hydroxy tamoxifen was established. SMAD1 phosphorylation in Bmpr2-deficient cells was markedly reduced by BMP4 but unaffected by BMP7. The sensitivity of SMAD2 phosphorylation by TGF-β1 was enhanced in the Bmpr2-deficient cells, and the inhibitory effect of TGF-β1-mediated SMAD2 phosphorylation by BMP4 was impaired in the Bmpr2-deficient cells. Furthermore, transcript levels of several known TGF-β downstream genes implicated in pulmonary hypertension were elevated in the Bmpr2-deficient cells. Taken together, these data suggest that SMAD1 is a critical mediator of BMPR2 signaling pertinent to PAH, and that an impaired balance between BMP4 and TGF-β1 may account for the pathogenesis of PAH.

Keywords: pulmonary arterial hypertension, BMPR2, SMAD1, pulmonary endothelial cells, conditional knock-out mice

Introduction

Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) is a rare but fatal vascular lung disease that is characterized by increased pulmonary vascular resistance and sustained elevation of mean pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP), leading to right ventricular hypertrophy and right heart failure. PAH is subclassified into idiopathic PAH (IPAH), heritable PAH (HPAH), drug- and toxin-induced PAH, persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, and PAH associated with other diseases, such as congenital heart defect, portal hypertension, HIV infection, connective tissue disease, schistosomiasis, and chronic hemolytic anemia.1 Pathological features of PAH include a narrowing and thickening of small pulmonary vessels and plexiform lesions. PAH patients exhibit pulmonary vascular remodeling of all layers of pulmonary arterial vessels: intimal thickening, smooth muscle cell hypertrophy or hyperplasia, adventitial fibrosis, and occluded vessels by in situ thrombosis.2

Genetic studies have shown that bone morphogenetic protein type 2 receptor (BMPR2), one of the receptors in transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily signaling, is responsible for heritable PAH in an autosomal dominant manner. A heterozygous BMPR2 mutation was found in nearly 70% of HPAH families and also in 25% of sporadic IPAH patients.3 Haploinsufficiency of BMPR2 is considered to be a primary mechanism underlying PAH with heterozygous BMPR2 mutations.4 The penetrance of PAH is incomplete: only about 20% of individuals with BMPR2 mutation develop the disease during their lifetime.3 This low penetrance suggests that a genetic predisposition due to BMPR2 mutations must be triggered by certain genetic or environmental factors in order to produce the clinical manifestations of PAH. Interestingly, BMPR2 is downregulated in the lung tissues of PAH patients not bearing a BMPR2 mutation,5 implying the wide-ranging influence of BMPR2-deficiency on PAH. Furthermore, BMPR2 signaling plays an important role in the survival of endothelial cells and in the migration and proliferation of smooth muscle cells.2;6 Taken together, impaired BMP signaling due to BMPR2 deficiency would be a considerable risk factor for the development of PAH.

TGF-β is a large cytokine family that contributes to diverse cellular processes, including cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis, pattern formation, and immunosuppression.7 TGF-β family members include TGF-βs, BMPs, growth and differentiation factors (GDFs), activins/inhibins, and müllerian inhibiting substance (MIS).8 TGF-β signal transduction is initiated by the binding of ligands to a heteromeric complex of transmembrane serine/threonine type 2 and type 1 receptors, which in turn activates receptor-regulated SMADs (R-SMADs): SMAD2/3 for TGF-βs/activins and SMAD1/5/8 for BMPs. R-SMADs then form a complex with a common partner, SMAD4 (Co-SMAD), which translocates to the nucleus and regulates the transcription of target genes. On the other hand, there is mounting evidence demonstrating that TGF-β/BMP signaling can be transduced through mediators other than SMADs, such as the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), including p38MAPK, p42/44MAPK (ERK1/2), and c-Jun-N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK).9 For instance, exogenous BMP ligands stimulate the phosphorylation of p38MAPK and p42/44MAPK and affect the proliferation of SMCs.10

Genetic studies with human subjects as well as mouse models clearly indicate that a deficiency in BMPR2 is a crucial genetic factor in PAH development.11–13 However, downstream mediators for BMPR2 signaling in PAH pathogenesis, remain unknown. About 20% of BMPR2 mutations occurred in the cytoplasmic tail domain, such as R899X, that does not impact SMAD phosphorylation, thereby indicating that SMAD proteins may not be the essential mediator of BMPR2 signaling in PAH pathogenesis. West et al. demonstrated that transgenic mice overexpressing the BMPR2(R899X) transgene in the smooth muscle cells of adult mice exhibited pulmonary hypertensive (PH) phenotypes,13 suggesting that SMAD may not be associated with PAH caused by BMPR2-deficiency. On the other hand, Yang et al. showed that SMAD1 phosphorylation was reduced in the pulmonary arterial SMCs of PAH patients with BMPR2 mutation.10

We investigated a cell-type specific role of SMAD1 in PAH pathogenesis by conditionally deleting the Smad1 gene either in ECs or in SMCs using a L1Cre or Tagln-Cre line, respectively. Smad1 deletion in either cell type resulted in the elevation of pulmonary pressure and the muscularization of pulmonary arteries, suggesting that SMAD1 is indeed a critical downstream molecule in PAH. Using pulmonary ECs (pECs), we further demonstrated that Bmpr2 deletion not only reduces the level of BMP4-mediated SMAD1/5 phosphorylation but also elevates the level of TGF-β-mediated SMAD2/3 phosphorylation, suggesting that the prevalence of TGF-β signaling in BMPR2-SMAD1 deficiency may contribute to the pathogenesis of PAH.

Materials and Methods

Detailed methods about mouse strains, mating scheme, hemodynamic analysis, right ventricular hypertrophy, pulmonary vessel morphometry, methods for establishment of immortalized pulmonary endothelial cells, culture conditions, semi-quantitative RT-PCR, Western blotting analysis, and statistical analysis are described in the online supplement.

Results

Smad1 deletion in pulmonary ECs or SMCs by L1Cre or Tagln-Cre

To investigate the role of SMAD1 in the pathogenesis of PAH, we exploited conditional knockout (cKO) approaches for deleting the Smad1 gene in ECs or SMCs by L1Cre or Tagln-Cre lines, respectively, because Smad1-null mice are embryonic lethal.14 Both L1Cre(+);Smad1f/f and Tagln-Cre(+);Smad1f/f mice were viable and did not exhibit any visible morphological defects as compared with their Cre-negative littermates. The Cre activity was monitored in several organs of 2 month-old mice -- including the lung, heart, liver, kidney, and spleen -- by detecting the Smad1-null allele. As expected based on our previous reports,12;15 the Cre-mediated Smad1 deletion was detected primarily in the lungs of L1Cre(+);Smad1f/f mice, whereas it was found in most organs of Tagln-Cre(+); Smad1f/f mice (Figure S1).

Elevated pulmonary pressure and right ventricular hypertrophy exhibited in some mice with Smad1 deletion in ECs or SMCs

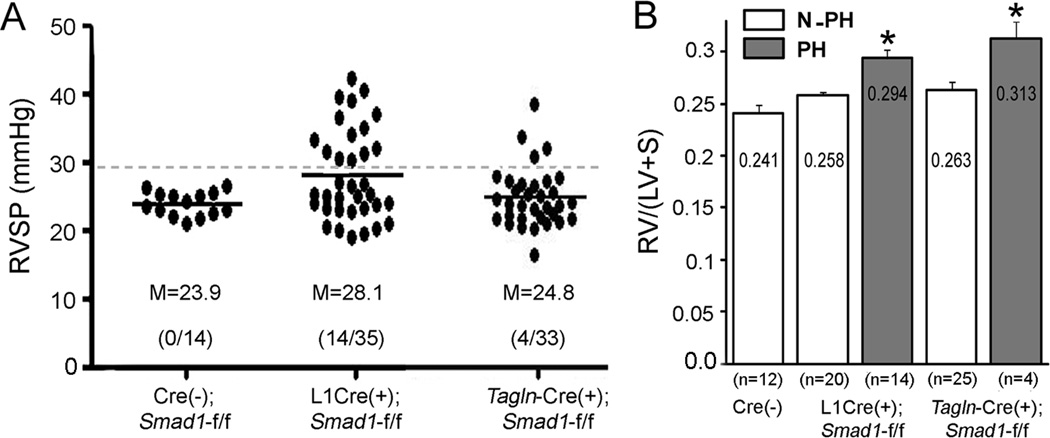

To assess pulmonary pressure, we measured the right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) of L1Cre(+);Smad1f/f and Tagln-Cre(+);Smad1f/f mice as well as of their age-matched Cre(−) control male and female mice at various ages (2–24 months). While the RVSPs of the controls were clustered in the 20–26 mmHg range, those of the L1Cre(+);Smad1f/f and Tagln-Cre(+);Smad1f/f mice were scattered across a wide range from 19 to 42 mmHg (Figure 1A). F-test for equal variance between L1Cre or Tagln-Cre and control groups showed significant differences (p < 0.0001) with these Smad1 mutant groups having wider spread of RVSPs than the control group. Brown-Forsythe test also showed that variances in the three groups (p<0.005), as well as in the combinations of two groups are not homogeneous: Cont vs. L1Cre (p=0.004), L1Cre vs. Tagln-Cre (p=0.035), and Cont vs. Tagln-Cre (p=0.053). When we combined RVSPs of control mice used in this study and others from our laboratory (n=81 mice, Table S1), the 99% confidence upper limit is calculated as 29.4. About 40% (14/35) of the L1Cre(+);Smad1f/f mice and 12% (4/33) of the Tagln-Cre(+);Smad1f/f mice had RVSPs greater than this boundary point, and we designated them as the PH group (Figure 1A). The Fulton index, the ratio of RV free wall weight over septum plus left ventricular free wall weight, was used to estimate RV hypertrophy. When we grouped the mutant mice into PH and non-PH groups, the Fulton index was greater in the PH mice than in the non-PH mice (Figure 1B), indicating that sustained elevation of pulmonary pressure might have resulted in RV hypertrophy in the PH groups. There was no significant correlation of RVSPs with gender and age (Figure S2), and also no difference in systemic blood pressure among Cre-negative controls and both Smad1-cKO mice (Figure S3).

Figure 1.

Elevated RVSP and RV weights in mice having Smad1-deletion in ECs or SMCs. A, Closed circles indicate RVSP of each mouse. About 40% and 12% of L1Cre(+);Smad1f/f and Tagln-Cre(+);Smad1f/f mice, respectively, had RVSPs greater than 29.4 mmHg indicated by a dotted line and were designated as the PH group. Means (M) of RVSP were indicated by horizontal bars. B, PH mice showed significantly higher RV hypertrophy than did Cre-negative controls and non-PH mice in both Smad1-conditional knockout (cKO) mouse lines. Statistical differences (p<0.05) were indicated by asterisks (*) above each bar.

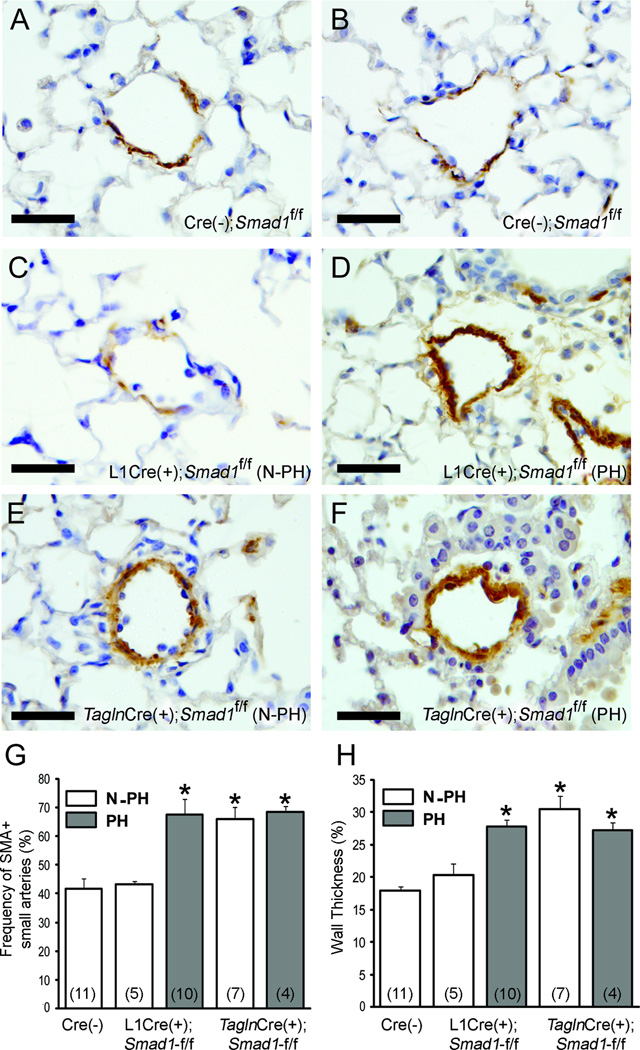

Increased number of αSMA-positive distal arteries and medial wall thickness in Smad1 mutant mice

To examine whether the elevated RVSP and RV hypertrophy in the Smad1-cKO mutants are associated with pulmonary vascular remodeling, anti-smooth muscle α-actin (αSMA)-positive pulmonary arteries ranging from 30–70 μm in diameter were counted, and the wall thickness was measured. In comparison with the Cre(−);Smad1f/f mice (Figures 2A and 2B) and the non-PH group L1Cre(+);Smad1f/f mice (Figure 2C), the PH group L1Cre(+);Smad1f/f mice (Figure 2D) had a higher number of αSMA-positive pulmonary arterioles and thicker arterial walls (Figures 2G and 2H). However, both non-PH and PH Tagln-Cre(+);Smad1f/f mice (Figures 2E and 2F) showed a higher number of muscularized vessels and thicker walls as compared with the Cre(−);Smad1f/f controls (Figures 2G and 2H). This unexpected data suggest that the thickening of pulmonary arterioles may not be the direct cause of pulmonary hypertension seen in these mutants. We observed higher percentages of perivascular leukocyte infiltration in both L1Cre(+);Smad1f/f (13/20) and Tagln-Cre(+);Smad1f/f (5/16) mice in comparison with Cre(−) controls (1/7), but plexiform-like complex vascular lesions were not observed.

Figure 2.

Morphometric analysis of pulmonary vessels of control and Smad1 mutants. A–F. representative pulmonary arterioles from Cre(−) controls (A, B), N-PH L1Cre(+);Smad1f/f (C), PH L1Cre(+);Smad1f/f (D), N-PH Tagln-Cre(+);Smad1f/f (E), and PH Tagln-Cre(+);Smad1f/f (F) were visualized by staining with anti-αSMA antibody. Scale bars represent 50 µm. PH mice of both Smad1-cKO mice showed muscularized vessels (G) and thickened vessel walls (H), as compared with Cre-negative controls. Interestingly, the N-PH group of Tagln-Cre(+);Smad1f/f also exhibited muscularized vessels with thickened vessels walls. Number of individual mice used for the morphometric analysis in each group is indicated by numbers with parentheses in G and H. Asterisks (*) indicate statistical difference (p<0.05) as compared with Cre-negative controls.

Isolation of pulmonary endothelial cells carrying R26CreER/+;Bmpr22f/2f alleles

It has been hypothesized that an opposing balance between TGF-β and BMP signalings is critical for the homeostasis of pulmonary vasculature and that an imbalance in TGF-β/BMP signalings may contribute to the pathogenesis of PAH.16 In order to investigate this hypothesis and to examine the extent to which Bmpr2 deficiency impacts this balance, an in vitro model system was established. We isolated pECs from the lung of a R26CreER/+;Bmpr22f/2f mouse, in which the conditional “2f” allele can be converted to a null “1f” allele by tamoxifen treatment that activates the Cre recombinase function. Three days of culturing the pECs with medium containing 1 μM 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4TM) efficiently deleted exons 4 and 5 of the Bmpr2 gene, resulting in conversion of the genotype from 2f/2f to 1f/1f (Figure S4A). When the Bmpr2-deleted cells were subsequently cultured with 4TM-free media for 10 days, no overgrowth of undeleted cell populations was observed (Figure S4B). Henceforth, Bmpr2-intact and -deleted cells will be designated as Bmpr22f/2f and Bmpr21f/1f cells, respectively.

To examine whether 4TM treatment and Bmpr2 deletion affected the expression of EC specific marker genes or other genes involved in TGF-β pathways, semi-quantitative RT-PCR analyses were performed. Expression of EC-specific markers including Nos3, Tie2, Eng, and Flk1 were maintained in Bmpr21f/1f pECs (Figure S4C). The Bmpr2 transcript level was undetectable, while transcripts for other TGF-β/BMP receptors were unchanged in Bmpr21f/1f pECs (Figure S4D).

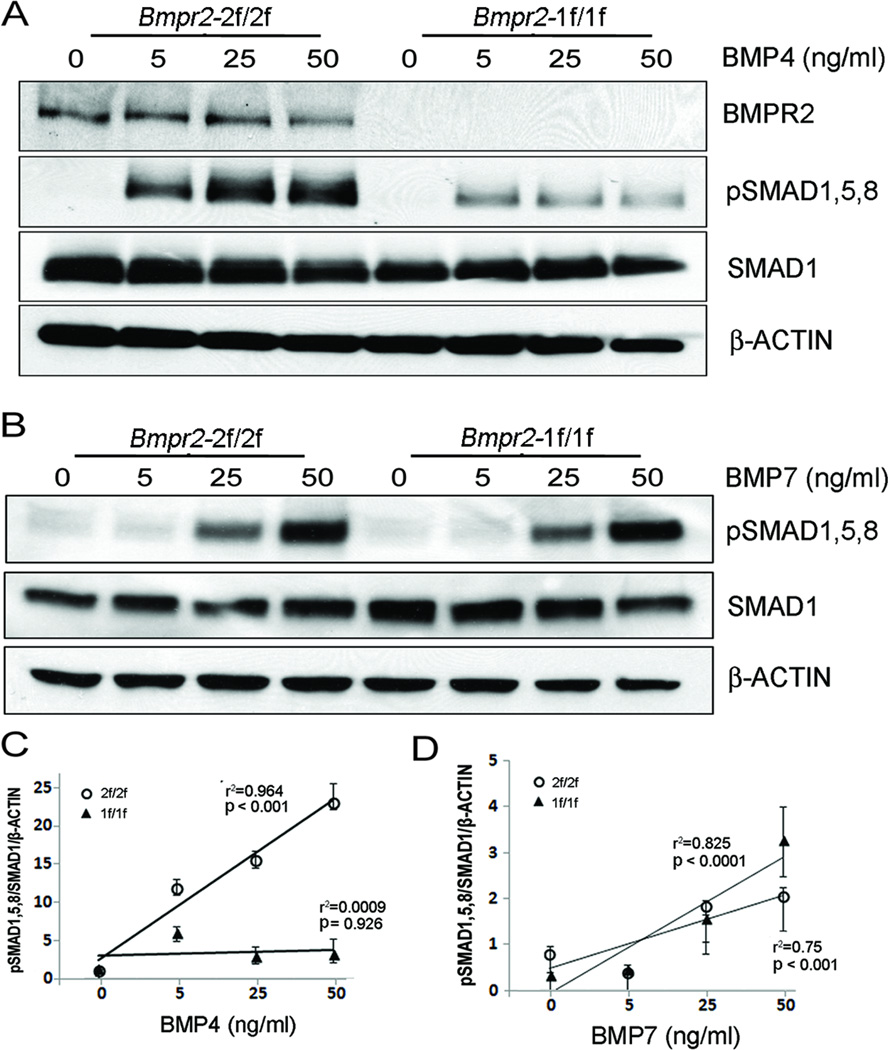

Deletion of the Bmpr2 gene and impaired BMP signaling

In order to assess the extent to which Bmpr2-deletion affects BMP signaling, BMP4 or BMP7 was added to Bmpr22f/2f and Bmpr21f/1f cells at various doses (0, 5, 25, and 50 ng/ml) after 16 hours of serum starvation. First, we examined the protein level of BMPR2 in these cells. While BMPR2 was readily detected in Bmpr22f/2f cells, BMPR2 protein was undetectable in Bmpr21f/1f cells (Figures 3A and 3B). The level of SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation was augmented in a dose-dependent manner in Bmpr22f/2f cells, whereas it was suppressed at all BMP4 doses in Bmpr21f/1f cells (Figures 3A and 3C), indicating that the BMP4 signaling is impaired in Bmpr21f/1f pECs. BMP7 signaling could be compensated by ACVR2A in BMPR2-deficient pulmonary artery SMCs (PASMCs).17 As shown in Figure 3D, phosphorylation of SMAD1/5/8 by BMP7 was elevated in a dose-dependent manner in both Bmpr22f/2f and Bmpr21f/1f cells, demonstrating that BMPR2 is not required for SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation by BMP7 in pECs.

Figure 3.

Impaired response to BMP4 but not to BMP7 in Bmpr2-deleted pECs. A, Western blot shows undetectable level of BMPR2 protein in pECs (1f/1f). Smad1,5,8 phosphorylation was increased in a dose-dependent manner at various concentrations (0–50 ng/ml) of BMP4 treatment for 30 minutes after serum starvation on Bmpr2-intact (Bmpr22f/2f) cells. The level of pSMAD1,5,8 by BMP4 was markedly reduced in Bmpr2-deleted pECs (Bmpr21f/1f) at all dosages. B. Phosphorylation of SMAD1/5/8 by BMP7 (0–50 ng/ml) was unaffected in Bmpr21f/1f cells. C and D, Statistical analysis of the Western blot data shown in A and B, respectively. pSMAD1,5,8/SMAD1/β-ACTIN ratio was increased in a dose-dependent manner by BMP4 in Bmpr22f/2f cells but not in Bmpr21f/1f cells (C). The levels of pSMAD1/5/8 were increased by BMP7 in both Bmpr22f/2f and Bmpr21f/1f cells. R square (r2) and p-values in regression analysis are indicated. Mean and standard error of data obtained from triplicate samples are shown at each data point.

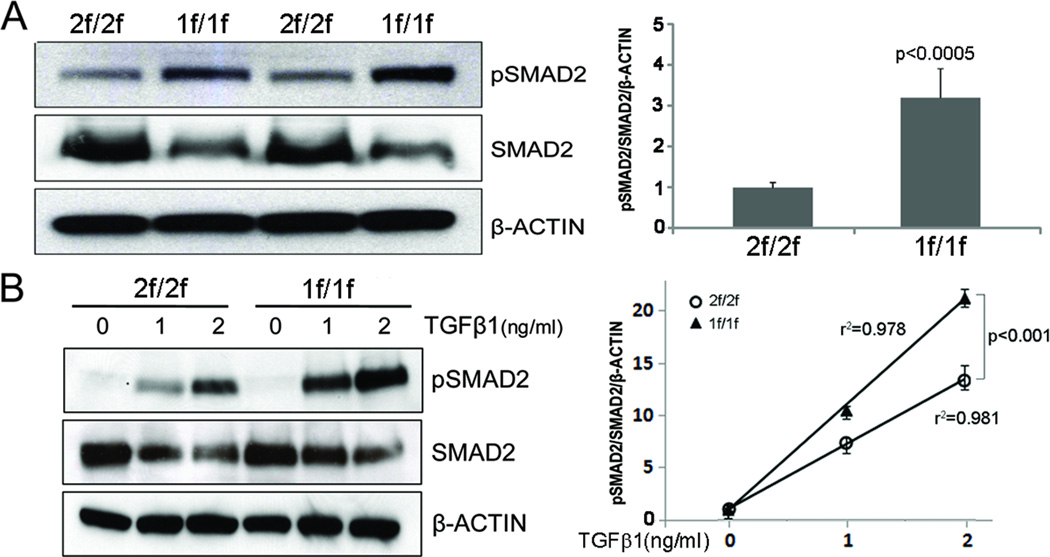

Enhanced TGF-β signaling in Bmpr2-deficient pECs

To investigate whether impaired BMP4 signaling affects TGF-β1 signaling, we first examined the basal level of SMAD2 phosphorylation in Bmpr22f/2f and Bmpr21f/1f cells cultured in medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Figure 4A). The level of pSMAD2 in Bmpr21f/1f cells was higher than that in Bmpr22f/2f cells. Reduced total SMAD2 levels in Bmpr21f/1f cells is likely due to ubiquitin ligase mediated degradation of activated SMAD2 (pSMAD2).18;19 To test if Bmpr2-deficient cells are more sensitive to TGF-β, we examined SMAD2 phosphorylation as a response to various doses of TGF-β1 treatments (0, 1, and 2 ng/ml) (Figure 4B). While both Bmpr22f/2f and Bmpr21f/1f cells showed a dose-dependent augmentation of pSMAD2, the level of SMAD2 phosphorylation was significantly higher in Bmpr21f/1f cells at 1 and 2 ng/ml TGF-β1 as compared with Bmpr22f/2f cells, suggesting that impaired BMPR2 signaling may potentiate the TGF-β signaling. In order to rule out the possibility that the observations seen in Bmpr21f/1f cells were due to off-target effects of 4TM treatment, we established immortalized Bmpr2WT pECs (Figure S5). In the Bmpr2WT pECs, 4TM treatment did not affect Bmpr2 expression (Figure S5), SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation by BMP4 (Figure S6A), and SMAD2 phosphorylation by TGF-β1 (Figure S6B). RT-PCR analysis shows that transcript levels of several downstream genes of TGF-β1 signaling implicated in pulmonary hypertension (Col3a1, Mmp9, Sema7a)20–23 were elevated in 4TM-treated Bmpr22f/2f (i.e. Bmpr21f/1f) cells (Fig. S7A), but such alterations were not observed in 4TM treated Bmpr2WT cells (Fig. S7B).

Figure 4.

Enhanced SMAD2 phosphorylation in Bmpr2-deleted pECs. A, Western blot shows elevated levels of pSMAD2 in Bmpr21f/1f cells cultured in media containing 10% fetal bovine serum without additional cytokine treatment. B, While SMAD2 phosphorylation was increased in both Bmpr22f/2f and Bmpr21f/1f cells dose-dependently by TGF-β1 treatment for 30 minutes after 16 hours of serum starvation, the response to TGF-β1 treatment was significantly enhanced in Bmpr21f/1f cells. R square (r2) and p-values in regression analysis are indicated. Mean and standard error of data obtained from triplicate samples are shown at each data point.

Opposing balance between TGF-β and BMP signalings in pECs

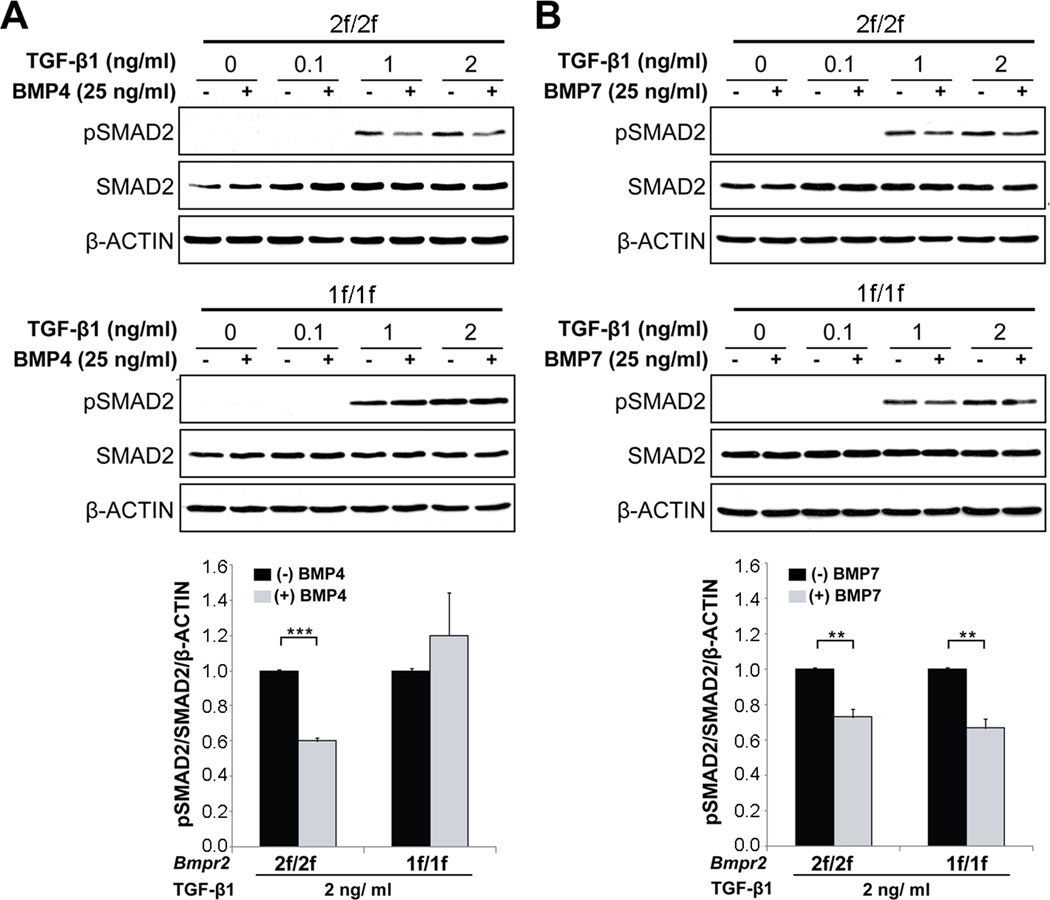

To further investigate whether BMP and TGF-β signaling form an opposing balance in pECs, we examined whether TGF-β-induced SMAD2 phosphorylation is suppressed by BMP treatment in pECs. TGF-β1 (0, 0.1, 1, and 2 ng/ml) and BMP4 (25 ng/ml) or BMP7 (25 ng/ml) were treated for 30 minutes after 16 hours of serum starvation in Bmpr22f/2f and Bmpr21f/1f cells. The level of pSMAD2 in 1 and 2 ng/ml of TGF-β1 treatment in Bmpr22f/2f cells was decreased by either BMP4 or BMP7, suggesting that BMP4/7 and TGF-β form an opposing balance in pECs (Figures 5A and 5B). However, the inhibitory effect of BMP4 treatment on TGF-β-mediated SMAD2 phosphorylation was blunted in Bmpr21f/1f cells (Figure 5A). Interestingly, BMP7 could suppress overactivated TGF-β signaling in Bmpr2-deficient pECs as well as in Bmpr2-intact pECs (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

BMP and TGF-β signalings form an opposing balance in pECs. A, Western blot analysis shows that SMAD2 phosphorylation by TGF-β1 (0–2 ng/ml) is inhibited by BMP4 (25 ng/ml) in BMPR2-intact 2f/2f cells, but this inhibitory effect of BMP4 is blunted in BMPR2-deficient 1f/1f cells. B, Inhibitory effect of BMP7 (25 ng/ml) on SMAD2 phosphorylation by TGF-β1 is unaffected in BMPR2-deficient pECs. Error bars are SEM (* p<0.05 and ** p<0.01).

Discussion

In this study, we showed that genetic ablation of Smad1 in ECs or SMCs can predispose mice to PAH, suggesting that the SMAD-dependent pathway in both vascular cell layers is critical for BMPR2 signaling pertinent to the pathogenesis of PAH. Our biochemical data from the Bmpr2 deficient pECs demonstrate the presence of an opposing balance between TGF-β1 and BMP4 signalings in pECs and suggest that not only diminished SMAD1 signaling but also enhanced TGF-β signaling may contribute to PAH development.

A growing body of evidence indicates that BMPR2 is a critical genetic factor in HPAH and also for other types of pulmonary hypertension.11 However, the downstream mediators of BMPR2 signaling have yet to be clearly defined. There have been incongruent reports about the role of SMAD1 as a downstream mediator of BMPR2 in PAH pathogenesis. Yang et al. reported that SMAD1 phosphorylation was diminished in the pulmonary vasculature of patients with a BMPR2 mutation, suggesting that inactivation of SMAD1 plays a role in PAH pathogenesis.10 In contrast to this, a significant number of BMPR2 mutations causing HPAH are within the cytoplasmic tail domain, which does not affect SMAD phosphorylation.24;25 Transgenic mice overexpressing a tail domain BMPR2 mutant (R899X) exhibited the PH phenotype,13 suggesting that SMAD may not be involved in PAH development. However, mutant BMPR2 mRNAs with most of the cytoplasmic tail mutations are destroyed through nonsense mutation decay (NMD),11 a cellular mechanism that destroys defective RNA transcripts having a nonsense mutation to block the production of truncated proteins.26 BMPR2(R899X) overexpressed in Tg (Bmpr2-R899X) mice was not destroyed by NMD and showed normal SMAD1 activation. Therefore, the mechanism of PAH development in a Tg (Bmpr2-R899X) mouse is likely to be different from that in a PAH patient with R899X mutation. However, it is possible that some PAH mice with BMPR2-tail domain mutations might be SMAD-independent by interrupting interactions between BMPR2 and the dynein light chain Tctex-1 as well as LIMK1, a key regulator of actin dynamics.27;28

Other studies have suggested the SMAD1-independent mechanism of PAH development in SMCs. Hansmann et al. presented a novel anti-proliferative BMP2-BMPR2-PPARγ-APOE axis in PAH.29 Mice with targeted deletion of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (Pparg) in SMCs spontaneously developed PAH with elevated RVSP, RVH, and increased muscularization of the distal pulmonary arteries. This was independent of SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation. Li et al. suggested a novel role of NOTCH3 in controlling the proliferation of SMCs and in maintaining SMCs in an undifferentiated state.30 The severity of the disease in human PAH patients and rodent PH models correlated with the amount of NOTCH3 protein in vascular SMCs of the lung, suggesting that the NOTCH3 signaling pathway in SMCs is crucial for the development of PAH.

About 40% and 12% of L1Cre(+);Smad1f/f and Tagln-Cre(+);Smad1f/f mice, respectively, displayed PH phenotypes, indicating that Smad1 deletion in endothelial cells has a greater impact on PAH pathogenesis than does Smad1 deletion in SMCs. The reason for this is unclear. One possible explanation is that while BMPR2-SMAD1 signaling in SMCs affects only SMC layer, that in pECs affects both EC and SMC layers. Defects in BMPR2-SMAD1 signaling in SMCs increase the proliferation of SMCs,10 leading to a thickening of vessel walls, whereas those in ECs may result in endothelial dysfunction,31 leading to neoinitima formation, a disrupted balance of vasoactive mediators exacerbating vasoconstriction, increased EC permeability allowing serum growth factors to affect SMC proliferation and the release of mitogens such as serotonin from ECs to induce smooth muscle hyperplasia,32 and enhanced vessel occlusion and in situ thrombosis.

Only a subset of mice with either endothelial or smooth muscle-Smad1 deletion displayed PH phenotypes. This incomplete penetrance could be due to functional redundancy among SMAD1, 5, and 8. Clear genetic interactions and mutual compensations between Smad1 and Smad5 in ECs have been reported.33 Because of the overlapping functions of these SMAD proteins and the embryonic lethality of homozygous mutations of individual Smad1, 5, or 4 genes, the association between SMAD mutations and PAH patients may be difficult to detect.34 Alternatively, strain-specific genetic modifiers that modulate susceptibility to environmental insults may contribute to PAH development. Inflammation has been suggested as such an environmental factor associated with PAH. Inflammatory cells, including macrophages and lymphocytes were accumulated, and many proinflammatory cytokines were elevated in the PAH vascular lesions.35 Thus, treatment with inflammatory stimulants such as IL-636 and 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO)37 on Smad1 cKO mice may increase penetrance. If so, blocking inflammatory activation could have therapeutic benefits for PAH patients. Supporting this view, platelet-activating factor (PAF) antagonists -- a class of anti-inflammatory drugs -- inhibited pulmonary vascular remodeling induced by hypobaric hypoxia in rats.38 Inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein (FLAP) suppressed hypoxia-induced pulmonary vasoconstriction in vitro and the development of chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in rats.39

Recent studies have implied that BMP and TGF-β signalings form an opposing balance in pulmonary vascular homeostasis and that the imbalance in TGF-β/BMP signaling may play an important role in PAH development.16 In order to investigate whether BMPR2 deficiency alters TGF-β signaling in pECs, we established immortalized pEC lines from a R26CreER+/−;Bmpr22f/2f mouse, in which tamoxifen treatment induces Bmpr2 deletion. This inducible system is advantageous because we can minimize variations due both to strain and individual differences and to passage numbers because Bmpr2-intact and Bmpr2-deficient cells originate from the same parental cells. Genetic ablation of the Bmpr2 gene by 4TM is also more efficient and reproducible as compared with knockdown approaches. Bmpr2-deleted pECs, as compared with Bmpr2-intact pECs, showed a markedly reduced level of pSMAD1/5/8 with BMP4 treatment as well as enhanced SMAD2 phosphorylation not only at the basal level but also with TGF-β1 treatment, demonstrating that Bmpr2-deficiency potentiates TGF-β signaling in pECs. Previous studies suggest that the TGF-β/BMP counter balance can occur at multiple levels, including activation of inhibitors of the opposing signal, inhibition of transcriptional targets of the opposing signal, and competition for SMAD440–42. Molecular mechanism for the antagonism warrants future investigation.

Our data from pECs indicate that restoration of the TGF-β/BMP balance could be an important therapeutic option for PAH. Supporting this view, recent reports have shown that the inhibition of TGF-β signaling by an ALK5 inhibitor (IN-1233) prevented PH in the monocrotalin-treated rat.43 Calpain44 or the inhibition of TGF-β signaling via an angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1)45 could be alternative therapeutic options for PAH. Our data and a previous report showed that BMP7 could phosphorylate SMAD1/5/8 in BMPR2-deficient pECs or SMCs.17 Therefore, restoration of pSMAD1/5/8 by BMP7 can be considered as a possible means to correct BMPR2 deficiency.

Perspectives

PAH is a rare but fatal disorder. The currently available therapies help to provide symptomatic relief, but a drug treatment based on the mechanisms of the disease has yet to be developed. A deficiency in BMPR2 signaling has been shown to be involved in sporadic as well as heritable forms of PAH. The first step toward developing a therapy is to discern whether a SMAD-dependent or -independent pathway is crucial for the pathogenesis of PAH. Here, using conditional knockout mouse models, we demonstrated that homozygous deletion of Smad1 in either ECs or SMCs resulted in PH, suggesting that the SMAD-dependent pathway is critical for PAH pathogenesis. Using a novel pulmonary EC line in which Bmpr2-deletion can be induced, we showed that BMPR2 is essential for SMAD1 phosphorylation by BMP4 but not by BMP7. We further demonstrated the presence of an opposing balance between BMP4 and TGF-β1 in the pECs and the causal relationship between Bmpr2-deficiency and enhanced TGF-β signaling. Our findings suggest that an impaired balance between TGF-β (SMAD2/3) and BMP4 (SMAD1/5/8) may underlie the pathogenesis of PAH and that correcting the imbalance -- i.e., either by enhancing SMAD1/5/8 or by inhibiting SMAD2/3 -- could be an effective strategy for developing a therapy for PAH.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is New?

With novel genetic mouse models and a novel pulmonary endothelial cell line, we demonstrate that SMAD1 is a crucial mediator of BMPR2 signaling in endothelial and smooth muscle cells pertinent to PAH, and that TGF-β and BMP form an opposing balance in pECs.

What Is Relevant?

We present SMAD-dependent pathway as a central mediator of BMPR2, the most well-known genetic factor for PAH. An impaired balance between TGF-β and BMP may underlie the pathogenesis of PAH, and correcting the imbalance either by enhancing BMP or by inhibiting TGF-β signalings could be an effective therapeutic strategy for PAH.

Summary

SMAD1 is an important downstream mediator of the PAH pathogenesis caused by Bmpr2-deficiency.

Acknowledgements

We thank Naime Filis for technical assistance in immunohistological analysis, Edward K. Chan (University of Florida) for providing reagents for immortalization, and Marya Park for editorial assistance.

Source of Funding

This work was supported by NHLBI (HL64024) to S.P.O., AHA predoctoral fellowship to YH Kim, and in part by World Class University program (WCU by Korean Ministry of Education, Science and Technology) to S.P.O.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Conflict of Interest

None

References

- 1.Simonneau G, Robbins IM, Beghetti M, Channick RN, Delcroix M, Denton CP, Elliott CG, Gaine SP, Gladwin MT, Jing ZC, Krowka MJ, Langleben D, Nakanishi N, Souza R. Updated Clinical Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;54:S43–S54. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Humbert M, Morrell NW, Archer SL, Stenmark KR, MacLean MR, Lang IM, Christman BW, Weir EK, Eickelberg O, Voelkel NF, Rabinovitch M. Cellular and molecular pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:13S–24S. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machado RD, Eickelberg O, Elliott CG, Geraci MW, Hanaoka M, Loyd JE, Newman JH, Phillips JA, Soubrier F, Trembath RC, Chung WK. Genetics and Genomics of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;54:S32–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, Thomson JR, Lane KB, Morgan NV, Wheeler L, Phillips JA, III, Newman J, Williams D, Galie N, Manes A, McNeil K, Yacoub M, Mikhail G, Rogers P, Corris P, Humbert M, Donnai D, Martensson G, Tranebjaerg L, Loyd JE, Trembath RC, Nichols WC. BMPR2 haploinsufficiency as the inherited molecular mechanism for primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:92–102. doi: 10.1086/316947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkinson C, Stewart S, Upton PD, Machado R, Thomson JR, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Primary pulmonary hypertension is associated with reduced pulmonary vascular expression of type II bone morphogenetic protein receptor. Circulation. 2002;105:1672–1678. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012754.72951.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teichert-Kuliszewska K, Kutryk MJ, Kuliszewski MA, Karoubi G, Courtman DW, Zucco L, Granton J, Stewart DJ. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor-2 signaling promotes pulmonary arterial endothelial cell survival: implications for loss-of-function mutations in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2006;98:209–217. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000200180.01710.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massague J, Blain SW, Lo RS. TGFbeta signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell. 2000;103:295–309. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massague J. How cells read TGF-beta signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:169–178. doi: 10.1038/35043051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang X, Long L, Southwood M, Rudarakanchana N, Upton PD, Jeffery TK, Atkinson C, Chen H, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Dysfunctional Smad signaling contributes to abnormal smooth muscle cell proliferation in familial pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res. 2005;96:1053–1063. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000166926.54293.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machado RD, Aldred MA, James V, Harrison RE, Patel B, Schwalbe EC, Gruenig E, Janssen B, Koehler R, Seeger W, Eickelberg O, Olschewski H, Elliott CG, Glissmeyer E, Carlquist J, Kim M, Torbicki A, Fijalkowska A, Szewczyk G, Parma J, Abramowicz MJ, Galie N, Morisaki H, Kyotani S, Nakanishi N, Morisaki T, Humbert M, Simonneau G, Sitbon O, Soubrier F, Coulet F, Morrell NW, Trembath RC. Mutations of the TGF-beta type II receptor BMPR2 in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:121–132. doi: 10.1002/humu.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong KH, Lee YJ, Lee E, Park SO, Han C, Beppu H, Li E, Raizada MK, Bloch KD, Oh SP. Genetic ablation of the BMPR2 gene in pulmonary endothelium is sufficient to predispose to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2008;118:722–730. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.736801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.West J, Harral J, Lane K, Deng Y, Ickes B, Crona D, Albu S, Stewart D, Fagan K. Mice expressing BMPR2(R899X) transgene in smooth muscle develop pulmonary vascular lesions. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2008;295:L744–L755. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90255.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lechleider RJ, Ryan JL, Garrett L, Eng C, Deng C, Wynshaw-Boris A, Roberts AB. Targeted mutagenesis of Smad1 reveals an essential role in chorioallantoic fusion. Dev Biol. 2001;240:157–167. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park SO, Lee YJ, Seki T, Hong KH, Fliess N, Jiang Z, Park A, Wu X, Kaartinen V, Roman BL, Oh SP. ALK5- and TGFBR2-independent role of ALK1 in the pathogenesis of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 2 (HHT2) Blood. 2008;111:633–642. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-107359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman JH, Phillips JA, III, Loyd JE. Narrative review: the enigma of pulmonary arterial hypertension: new insights from genetic studies. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:278–283. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu PB, Beppu H, Kawai N, Li E, Bloch KD. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type II receptor deletion reveals BMP ligand-specific gain of signaling in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24443–24450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonni S, Wang HR, Causing CG, Kavsak P, Stroschein SL, Luo K, Wrana JL. TGF-beta induces assembly of a Smad2-Smurf2 ubiquitin ligase complex that targets SnoN for degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:587–595. doi: 10.1038/35078562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo RS, Massague J. Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of TGF-beta-activated smad2. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:472–478. doi: 10.1038/70258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farkas L, Farkas D, Ask K, Moller A, Gauldie J, Margetts P, Inman M, Kolb M. VEGF ameliorates pulmonary hypertension through inhibition of endothelial apoptosis in experimental lung fibrosis in rats. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;119:1298–1311. doi: 10.1172/JCI36136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang HR, Lee CG, Homer RJ, Elias JA. Semaphorin 7A plays a critical role in TGF-beta(1)-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204:1083–1093. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.George J, D'Armiento J. Transgenic expression of human matrix metalloproteinase-9 augments monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension in mice. Journal of Hypertension. 2011;29:299–308. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328340a0e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chou YT, Wang H, Chen Y, Danielpour D, Yang YC. Cited2 modulates TGF-beta-mediated upregulation of MMP9. Oncogene. 2006;25:5547–5560. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishihara A, Watabe T, Imamura T, Miyazono K. Functional heterogeneity of bone morphogenetic protein receptor-II mutants found in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3055–3063. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rudarakanchana N, Flanagan JA, Chen H, Upton PD, Machado R, Patel D, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Functional analysis of bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor mutations underlying primary pulmonary hypertension. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1517–1525. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.13.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khajavi M, Inoue K, Lupski JR. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay modulates clinical outcome of genetic disease. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2006;14:1074–1081. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Machado RD, Rudarakanchana N, Atkinson C, Flanagan JA, Harrison R, Morrell NW, Trembath RC. Functional interaction between BMPR-II and Tctex-1, a light chain of Dynein, is isoform-specific and disrupted by mutations underlying primary pulmonary hypertension. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3277–3286. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foletta VC, Lim MA, Soosairaiah J, Kelly AP, Stanley EG, Shannon M, He W, Das S, Massague J, Bernard O. Direct signaling by the BMP type II receptor via the cytoskeletal regulator LIMK1. Journal of Cell Biology. 2003;162:1089–1098. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansmann G, Perez VAD, Alastalo TP, Alvira CM, Guignabert C, Bekker JM, Schellong S, Urashima T, Wang L, Morrell NW, Rabinovitch M. An antiproliferative BMP-2/PPAR gamma/apoE axis in human and murine SMCs and its role in pulmonary hypertension. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118:1846–1857. doi: 10.1172/JCI32503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li XD, Zhang XX, Leathers R, Makino A, Huang CQ, Parsa P, Macias J, Yuan JXJ, Jamieson SW, Thistlethwaite PA. Notch3 signaling promotes the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nature Medicine. 2009;15:1289–1U89. doi: 10.1038/nm.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Budhiraja R, Tuder RM, Hassoun PM. Endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2004;109:159–165. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000102381.57477.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eddahibi S, Guignabert C, Barlier-Mur AM, Dewachter L, Fadel E, Dartevelle P, Humbert M, Simonneau G, Hanoun N, Saurini F, Hamon M, Adnot S. Cross talk between endothelial and smooth muscle cells in pulmonary hypertension: critical role for serotonin-induced smooth muscle hyperplasia. Circulation. 2006;113:1857–1864. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moya IM, Umans L, Maas E, Pereira PNG, Beets K, Francis A, Sents W, Robertson EJ, Mummery CL, Huylebroeck D, Zwijsen A. Stalk Cell Phenotype Depends on Integration of Notch and Smad1/5 Signaling Cascades. Developmental Cell. 2012;22:501–514. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nasim MT, Ogo T, Ahmed M, Randall R, Chowdhury HM, Snape KM, Bradshaw TY, Southgate L, Lee GJ, Jackson I, Lord GM, Gibbs JSR, Wilkins MR, Ohta-Ogo K, Nakamura K, Girerd B, Coulet F, Soubrier F, Humbert M, Morrell NW, Trembath RC, Machado RD. Molecular genetic characterization of SMAD signaling molecules in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Human Mutation. 2011;32:1385–1389. doi: 10.1002/humu.21605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Price LC, Wort SJ, Perros F, Dorfmuller P, Huertas A, Montani D, Cohen-Kaminsky S, Humbert M. Inflammation in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Chest. 2012;141:210–221. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steiner MK, Syrkina OL, Kolliputi N, Mark EJ, Hales CA, Waxman AB. Interleukin-6 Overexpression Induces Pulmonary Hypertension. Circulation Research. 2009;104:236–U208. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song Y, Jones JE, Beppu H, Keaney JF, Jr, Loscalzo J, Zhang YY. Increased susceptibility to pulmonary hypertension in heterozygous BMPR2-mutant mice. Circulation. 2005;112:553–562. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ono S, Westcott JY, Voelkel NF. Paf Antagonists Inhibit Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling Induced by Hypobaric Hypoxia in Rats. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1992;73:1084–1092. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.3.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voelkel NF, Tuder RM, Wade K, Hoper M, Lepley RA, Goulet JL, Koller BH, Fitzpatrick F. Inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein (FLAP) reduces pulmonary vascular reactivity and pulmonary hypertension in hypoxic rats. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;97:2491–2498. doi: 10.1172/JCI118696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sander V, Eivers E, Choi RH, De Robertis EM. Drosophila Smad2 Opposes Mad Signaling during Wing Vein Development. Plos One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Candia AF, Watabe T, Hawley SHB, Onichtchouk D, Zhang Y, Derynck R, Niehrs C, Cho KWY. Cellular interpretation of multiple TGF-beta signals: intracellular antagonism between activin/BVg1 and BMP-2/4 signaling mediated by Smads. Development. 1997;124:4467–4480. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamamoto M, Beppu H, Takaoka K, Meno C, Li E, Miyazono K, Hamada H. Antagonism between Smad1 and Smad2 signaling determines the site of distal visceral endoderm formation in the mouse embryo. Journal of Cell Biology. 2009;184:323–334. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Long L, Crosby A, Yang XD, Southwood M, Upton PD, Kim DK, Morrell NW. Altered Bone Morphogenetic Protein and Transforming Growth Factor-beta Signaling in Rat Models of Pulmonary Hypertension Potential for Activin Receptor-Like Kinase-5 Inhibition in Prevention and Progression of Disease. Circulation. 2009;119:566–U150. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.821504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma WL, Han WH, Greer PA, Tuder RM, Toque HA, Wang KKW, Caldwell RW, Su YC. Calpain mediates pulmonary vascular remodeling in rodent models of pulmonary hypertension, and its inhibition attenuates pathologic features of disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121:4548–4566. doi: 10.1172/JCI57734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Habashi JP, Judge DP, Holm TM, Cohn RD, Loeys BL, Cooper TK, Myers L, Klein EC, Liu G, Calvi C, Podowski M, Neptune ER, Halushka MK, Bedja D, Gabrielson K, Rifkin DB, Carta L, Ramirez F, Huso DL, Dietz HC. Losartan, an AT1 antagonist, prevents aortic aneurysm in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome. Science. 2006;312:117–121. doi: 10.1126/science.1124287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.