Abstract

Background and Purpose

Remote ischemic conditioning is cardioprotective in myocardial infarction and neuroprotective in mechanical occlusion models of stroke. However, there is no report on its therapeutic potential in a physiologically relevant embolic stroke model (eMCAO) in combination with intravenous (IV) tissue plasminogen activator (tPA).

Methods

We tested remote ischemic perconditioning therapy (RIPerC) at 2 hours after eMCAO in the mouse with and without IV tPA at 4 hours. We assessed cerebral blood flow (CBF) up to 6 hours, neurologic deficits, injury size and phosphorylation of Akt (Serine473; p-Akt) as a pro-survival signal in the ischemic hemisphere at 48 hours post stroke.

Results

RIPerC therapy alone improved the CBF and neurologic outcomes. tPA alone at 4 hours did not significantly improve the neurologic outcome even after successful thrombolysis. Individual treatments with RIPerC and IV tPA reduced the infarct size (25.7% and 23.8%, respectively). Combination therapy of RIPerC and tPA resulted in additive effects in further improving the neurologic outcome, and reducing the infarct size (50%). All the therapeutic treatments upregulated p-Akt in the ischemic hemisphere.

Conclusions

RIPerC is effective alone after eMCAO and has additive effects in combination with IV tPA. RIPerC may be a simple, safe and inexpensive combination therapy with IV tPA.

Keywords: Embolic stroke, Remote Ischemic Conditioning, IV tPA

The Stroke Academic Industry Roundtable (STAIR) recommends therapeutic evaluation of neuroprotective agents in combination with intravenous (IV) tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), and to develop therapies to reduce reperfusion injury.1 After so many failed pharmacological trials in stroke, harnessing endogenous pathways of protection provides another promising but untraveled avenue.2 Murry et al. first introduced the ischemic preconditioning (IPC) therapy in a canine myocardial infarction (MI) model and follow-up studies have shown IPC to provide the most consistent and profound reduction in infarct size of all cardioprotective interventions.3,4 Subsequent studies have shown that ischemic conditioning can also be applied “at a distance” so called “remote ischemic conditioning”; brief episodes of ischemia-reperfusion in a distant organ such as the limb can provide protection to the ischemic heart or brain.5 Remote ischemic conditioning can also be applied during the ischemia and before reperfusion (perconditioning; RIPerC) or after reperfusion (post-conditioning; RIPostC). RIPerC therapy can be simply performed using a blood pressure cuff on the arm and has been found protective in a pre-hospital clinical trial of MI.6 A number of studies have now shown that limb RIPerC and RIPostC are protective in animal models of stroke.7,8

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) restoration is critical for neurovascular protection after stroke and requires stringent monitoring.9,10 Neurovascular protection conferred by ischemic conditioning is also mediated through vasodilatory factors and improvements in CBF.11,12 Embolic clot model of stroke (eMCAO) better represents the majority of the human stroke cases, and is more suitable to study thrombolytics such as tPA and related reperfusion injury.13-15

To the best of our knowledge, none of the above conditioning strategies have been ever reported in a physiologically relevant eMCAO model in combination with IV tPA. Since most of the stroke victims within a 4.5 hours treatment window will be candidates for IV tPA, it is necessary to know the effect of RIPerC therapy, and its additional benefits and safety with tPA treatment. We herein report that RIPerC therapy is effective alone and provides further additional benefits in combination with IV tPA in a murine eMCAO model.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Experimental Groups

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Georgia Health Sciences University (GHSU) approved the experimental procedures as per the National Institute of Health guidelines. 90 C57BL/6J wild type male mice (20 ±1 weeks old; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) housed in GHSU's AAALAC accredited facility were used in the following two experiments: Experiment I was performed to determine the effects of treatments on CBF using laser doppler flowmeter (LDF; PeriFlux 5001, Perimed Inc., Sweden), neurologic outcome and infarct size. The groups (N=10) were: eMCAO+Veh group, embolic stroke (eMCAO) with RIPerC sham procedure followed by IV sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) treatment; eMCAO+RIPerC group, eMCAO treated with RIPerC therapy followed by IV PBS treatment; eMCAO+tPA group, eMCAO with RIPerC sham procedure followed by IV tPA (10 mg / kg) treatment; and eMCAO+RIPerC+tPA group, eMCAO treated with RIPerC therapy followed by IV tPA treatment. All the groups were euthanized at 48 hours post eMCAO. Experiment II was performed in a separate set of animals with the same groups as described in Experiment I, but the tissue extracts were used for immunoblot analysis for phosphorylation of Akt (Serine473; p-Akt). Experiment II also included a Sham group for stroke and RIPerC sham procedures followed by PBS infusion. Animals were also scanned for cerebral perfusion with a laser doppler imaging system (LDIS; PeriScan PIM3 System, Perimed Inc.) by an investigator blinded to the groups.

Procedures and Treatment Protocols

The mice were marked for identity and numbered. In Experiment I, the mice were randomized in a block size of 4 (4 animals from the same cage) to the different treatment groups after the stroke surgery. The surgeon performing the stroke and RIPerC surgeries, and the investigators performing RIPerC sham procedure or therapy, and intravenous treatments were blinded to the final identity of the groups and to the intravenous treatments (PBS or tPA). In Experiment I, an investigator blindly scored the animals for neurologic deficits before euthanasia. Mortality was monitored daily using a mortality chart. In Experiment II (5 mice per cage), 1 mouse from each cage was randomly picked for Sham group and performance of related procedures. The remaining 4 mice in each cage were randomized for the different treatments as discussed above for Experiment I.

Stroke induction, CBF measurements and cerebral perfusion imaging, neurologic score based on Bederson scale, infarct size measurements after 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining and immunoblot analysis were performed as described in our previous report with slight modifications.16 To induce stroke, human fibrinogen supplemented clot was prepared as reported earlier.16 Briefly, a modified catheter containing 9.0±0.5-mm long clot was inserted into the right external carotid artery, advanced into the internal one and the clot was gently delivered into the brain. Wherever required, either RIPerC sham procedure or RIPerC therapy was performed at 2 hours after eMCAO in the left hind limb as reported earlier (5 cycles/ 5 minute duration/ 5 minute interval between each cycle).8 Moreover, either tPA (10 mg/kg body weight), or PBS was infused intravenously at 4 hours post eMCAO as 10% bolus, and the balance over a period of 20 minutes in a volume of 0.1 mL/ 10 g body weight of the mouse.

Statistical Analyses

From our previous experience with adult male mice in eMCAO model, we anticipated stroke injury size to be 50±10% in eMCAO+Veh group. Individual treatment with tPA or RIPerC was hypothesized to reduce the infarct size by 20% to 40±10% and the combined treatment by 50% to 25±10%. A sample size of 7 in each group would provide 88% power at alpha=0.05 to detect the main effects due to tPA and RIPerC individual treatments. Also based on our experience, mortality up to 30% was anticipated for some groups over the survival period of 48 hours. Therefore, 10 mice were randomized to each of 4 groups to achieve a power of greater than 80%. All the data are expressed as mean ±SD. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A 2 RIPerC (no vs. yes) by 2 tPA (no vs. yes) ANOVA with interaction was used to analyze “within time CBF”, neurologic score, stroke injury, and p-Akt outcomes. In the absence of a significant interaction, the main effects are considered to be additive when combined. One-way ANOVA was only used to compare p-Akt level for Sham vs. other four groups using Dunnett's test in experiment II. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05.

Results

RIPerC therapy alone or in combination with IV tPA treatment improved the CBF and neurologic outcome

Figures 1A and 1B show significant effect of RIPerC therapy in improving the CBF after eMCAO as compared to RIPerC sham operated group (RIPerC effect, p=0.024 at 4 hours post eMCAO; p=0.0035 at 6 hours). Late tPA therapy also improved the CBF significantly (tPA effect p<0.0001 at 6 hours post eMCAO). Late tPA infusion was not as efficient as early tPA treatment in improving the CBF (please see Supplementary Figure S1A). RIPerC therapy showed an additive effect with tPA treatment in further improving the CBF. However, there was no interaction between the two treatments (interaction effect, p=0.664 at 6 hours post eMCAO).

Figure 1.

A. CBF measured with LDF and presented as percent of pre-ischemic value (N=10). Comparisons between the groups were done “within the time point”. B. Representative images of cerebral perfusion detected with LDIS at 5 hours post eMCAO. The CBF values in the panels are as compared to the contralateral sides. C. Neurologic score as evaluated on Bederson scale at 48 hours post eMCAO in Experiment I. eMCAO+Veh (N=7 survived out of 10; 7/10), eMCAO+RIPerC (N=8/10), eMCAO+tPA (N=8/10) and eMCAO+RIPerC+tPA (N=10/10). Data presented as Mean ±SD. Pairs of Means with different letters are significantly different, p < 0.05.

At 48 hours after eMCAO the main effects of RIPerC and tPA on the neurologic outcome were significant (p=0.0005 and p=0.05, respectively; Figure 1C). No significant (p=0.78) interaction effect on the neurologic outcome was found between the two treatments such that RIPerC therapy provided a significant additive effect to the tPA treatment. RIPerC significantly improved the neurologic outcome in eMCAO+RIPerC group as compared to eMCAO+Veh (1.88±0.23 vs 3.0±0.22; p=0.0084). tPA treatment alone in eMCAO+tPA group did not improve the neurologic outcome significantly as compared to eMCAO+Veh (2.38±0.42 vs 3.0±0.22; p=0.13). There were no significant differences found in the neurologic outcomes between eMCAO+RIPerC and eMCAO+tPA groups (p=0.20). On the other hand, combination therapy in eMCAO+RIPerC+tPA group significantly improved the neurologic outcome as compared to eMCAO+Veh (1.4±0.16 vs 3.0±0.22; p=0.0002) and eMCAO+tPA (p=0.012).

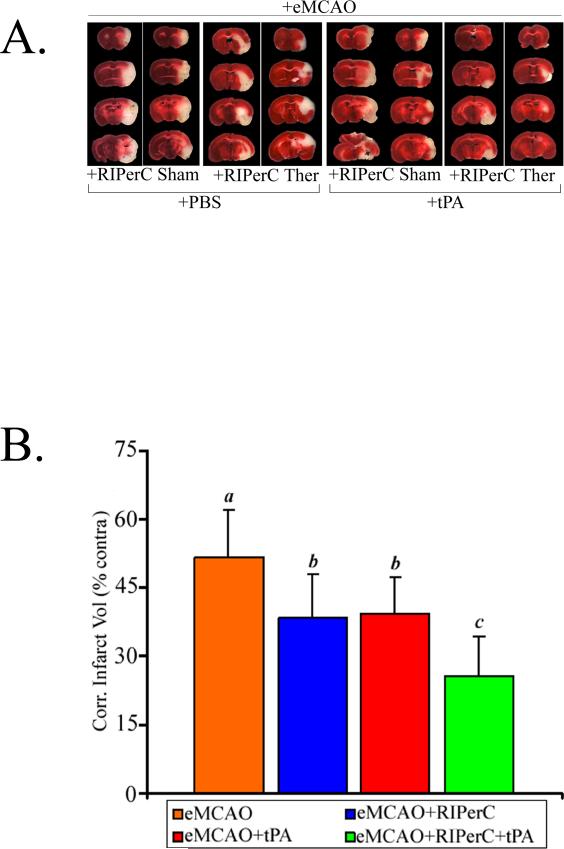

RIPerC therapy alone or in combination with IV tPA treatment reduced the injury size

Figures 2A and 2B show the representative images of TTC stained coronal sections of the brain and infarct volumes, respectively. The analysis of effects on the infarct volume reduction indicates that the main effects of RIPerC and tPA were significant (p=0.0002 and p=0.0005, respectively) but their interaction was not significant (p=0.97). RIPerC therapy alone in eMCAO+RIPerC group significantly reduced the injury size as compared to eMCAO+Veh (25.7% relative reduction; 38.4±9.5 vs 51.7±10.4; p=0.0082). tPA treatment alone in eMCAO+tPA group also reduced the injury size as compared to the eMCAO+Veh (23.8% relative reduction; 39.4±7.8 vs 51.7±10.4; p=0.014). There was no significant difference in the infarct volumes between eMCAO+RIPerC and eMCAO+tPA groups (p=0.82). Combination therapy in eMCAO+RIPerC+tPA group significantly reduced the infarct size (50.0% relative reduction; 25.8±8.6 vs 51.7±10.4) as compared to the eMCAO+Veh (p < 0.001), and also when compared to the individual treatments groups (p=0.0037 vs eMCAO+RIPerC, and p=0.0067 vs eMCAO+tPA).

Figure 2.

A. Representative TTC stained coronal sections, and B. Means of the corrected infarct volumes calculated as percent of their corresponding contralateral sides. Data are presented as Mean ±SD (N = as above in Figure 1C). Pairs of Means with different letters are significantly different, p < 0.05.

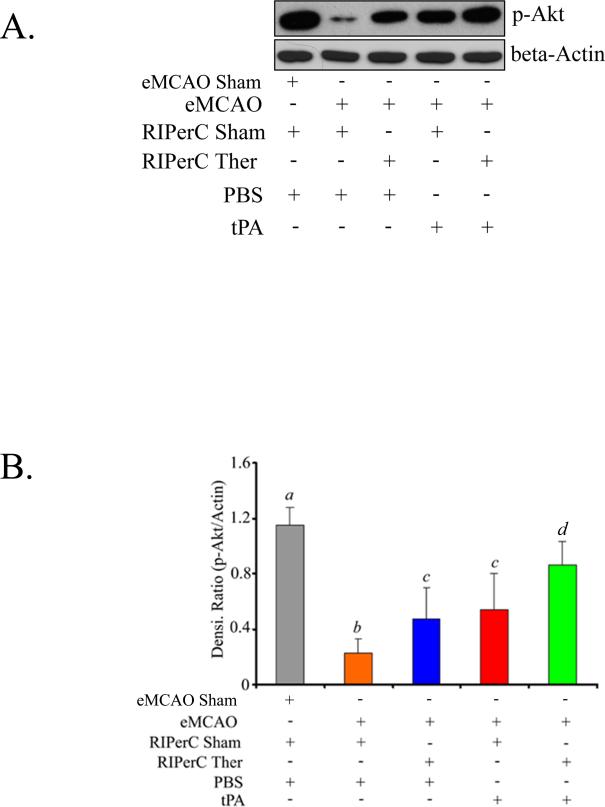

RIPerC therapy prolonged the Akt activation in the ischemic hemisphere

Figures 3A and 3B show that p-Akt, a pro-survival signal after experimental stroke and ischemic conditioning therapy,17,18 was upregulated by both the individual treatments and their combination. All the eMCAO groups had significantly lower level of p-Akt when compared to Sham at 48 hours. p-Akt level was significantly downregulated in eMCAO+Veh group as compared to Sham (p<0.0001). The analysis of effects on the p-Akt level indicated that the main effects of RIPerC and tPA were significant (p=0.0026 and p=0.0004, respectively) but their interaction was not significant (p=0.67). Both eMCAO+RIPerC and eMCAO+tPA groups had significantly increased p-Akt level as compared to eMCAO+Veh (p=0.046 and p=0.014, respectively). There was no significant difference in p-Akt level between eMCAO+RIPerC and eMCAO+tPA groups (p=0.57). Combination therapy in eMCAO+RIPerC+tPA group significantly increased p-Akt as compared to eMCAO+Veh (p < 0.001), and also when compared to the individual treatments (p=0.0034 vs eMCAO+RIPerC, and p=0.013 vs eMCAO+tPA).

Figure 3.

p-Akt (Ser473) level as detected by immunoblot analysis in the ischemic hemispheres at 48 hours post eMCAO in Experiment II. A. Representative immunoblot image, and B. Densitometric analysis of immunoreactive bands normalized to β-actin as loading control. Data are presented as Mean ±SD (N=6). Pairs of Means with different letters are significantly different, p < 0.05.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating the efficacy of RIPerC therapy alone and in combination with IV tPA in a physiological and clinically relevant embolic model. The key findings are that RIPerC alone increased the CBF and pro-survival signaling after stroke, resulting in improved neurologic outcome and reduction in the size of injury. We also found additive beneficial effects of RIPerC to “late” IV tPA treatment leading to further improvements in the neurologic outcome and reduction of injury size. Late IV tPA reduced the infarct size but did not improve the neurologic outcome.

More than 60% of pre-clinical studies for neuroprotection in stroke research are done using well-accepted mechanical vascular occlusion-reperfusion models.14 This closely resembles the clinical cases of reperfusion after thrombectomy. In a mechanical stroke model, postconditioning by interrupting sudden reperfusion attenuated the injury.19 On the other hand, opening of the blood vessels after eMCAO either by spontaneous recanalization or by thrombolysis is often gradual and/ or partial, which leads to prolonged microcirculatory and reperfusion deficits. Therefore, eMCAO better models the majority of human stroke cases and may be more appropriate for further translational and mechanistic studies of the conditioning therapies.

CBF restoration is a promising target for the treatment of stroke.9,10,13 As evident from Figures 1 and 2, RIPerC therapy significantly increased the CBF, resulting in significant improvements in the neurologic outcomes and infarct size reductions. Moreover, tPA being a thrombolytic, also improved the CBF when infused alone at 4 hours post eMCAO. tPA alone reduced the injury size but did not significantly improve the neurologic outcome, possibly because of its unwanted effects in a few animals.20,21

It should be noted that IV tPA was given at the “tail” of the protective window where it still had some effect on infarct size reduction. This effect of tPA was mainly due to opening of the major occluded arteries as detected with LDF (Figures 1A-B), and visualized by clot resolution (Supplementary Figures S1C).21 In the absence of RIPerC therapy, 4 hours of untreated ischemia may have caused microvascular dysfunction, which prevented the complete CBF restoration even after successful thrombolysis by late tPA infusion (Figures 1A-B and Supplementary Figures S1A-C).21,22 This may be due to increased oxidative-nitrative stress after eMCAO (Supplementary Figures S2C-E), which impairs capillary reflow despite successful opening of an occluded artery.22 Increased nitrative stress also impairs clot lysis, and correlated with the poor neurologic outcomes after stroke in human.23-26 In fact, we observed more prominent and sudden increase in the nitrative stress level 3 hours post eMCAO both in the plasma and brain (Supplementary Figures S2C-E), a critical time point after which the benefits and safety of tPA therapy start to decline. Mild to moderate hemorrhage after “tPA alone” treatment was found in a few animals at this tail of the protective window but it was attenuated when RIPerC therapy was performed 2 hours before tPA infusion (Supplementary Figures S1C-D). Due to improvement in the CBF, RIPerC may have attenuated the neurovascular stress before tPA treatment, resulting into a “preconditioned” window for a safer late tPA therapy and additional benefits.

The molecular mechanisms of remote ischemic conditioning are still elusive and may be multi-factorial.27 The downstream effects of multiple mechanisms appear to converge on the upregulation of reperfusion injury salvage kinase (RISK) pathway and blocking of opening of the mitochondrial transition permeability pore.28 PI3K/Akt is a key pro-survival signal of RISK pathway, and may have important physiological effects. Pharmacological inhibition of PI3K/Akt activity abolished the protective effects of PostC on the infarct size reduction.17,18 We found that Akt activity after eMCAO in the untreated mice was “transient”. p-Akt level started declining after 3 hours, and appeared to be correlated with the increasing nitrative stress of the plasma and brain (Supplementary Figures S2A-E). RIPostC attenuated nitrotyrosine in the brain, a marker of increased nitrative stress.29 Peroxynitrite also inhibits PI3K, a major upstream kinase and regulator of Akt activity.30 Therefore, we tested RIPerC therapy at 2 hours post eMCAO. As evident from our supplementary data and Figure 3, RIPerC preserved and prolonged the post eMCAO Akt activation, which was sustained even up to 48 hours. In agreement with previous findings,17,18 prolonged Akt activation may have improved the post eMCAO outcomes. Because of its recanalization effect, tPA alone also upregulated the p-Akt level at the end point which was further increased due to additive effects of RIPerC.

In this study, increased p-Akt level after the treatments may be related to both the vasculature and brain. Therefore, future studies in animals genetically mutated for different Akt isoforms are planned. In the endothelium, Akt activity increases nitric oxide (NO) production via improved endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity and helps to maintain vascular homeostasis.31,32 Since RIPerC prolonged the Akt activity and improved the CBF, the beneficial “neuroprotective” effects of RIPerC is likely to be partially related to improvements in the microvascular blood flow. Future studies on collateral and microvascular CBF modulation by RIPerC are in progress, which will help us to better understand the mechanism of neurovascular protection by this therapy in eMCAO.

In summary, the above findings could be helpful in translating the remote ischemic conditioning into stroke clinical trials. Further studies to test the therapeutic potential of RIPerC in a window later than 4 hours and in aged animals of both sexes with and without comorbidities such as diabetes will better inform and facilitate a clinical trial. However, remote ischemic conditioning is promising and may open a new paradigm in stroke treatment, which may be safe, inexpensive, and generalizable to a wide variety of stroke systems of care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

NIH 1R01NS055728 award to DCH; VA Merit (BX000347) and NIH NS070239 awards to AE; VA Merit (BX000891) and NIH NS063965 awards to SCF; VA 104462 merit award to WDH. Financial supports from Augusta Biomedical Research Corporation and Immunotherapy Discovery Institute at GHSU to MNH are also acknowledged.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Albers GW, Goldstein LB, Hess DC, Wechsler LR, Furie KL, Gorelick PB, et al. Stroke treatment academic industry roundtable (stair) recommendations for maximizing the use of intravenous thrombolytics and expanding treatment options with intra-arterial and neuroprotective therapies. Stroke. 2011;42:2645–2650. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.618850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iadecola C, Anrather J. Stroke research at a crossroad: Asking the brain for directions. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1363–1368. doi: 10.1038/nn.2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: A delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74:1124–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vander Heide R. Clinically useful cardioprotection: Ischemic preconditioning then and now. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2011;16:251–254. doi: 10.1177/1074248411407070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Przyklenk K, Whittaker P. Remote ischemic preconditioning: Current knowledge, unresolved questions, and future priorities. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2011;16:255–259. doi: 10.1177/1074248411409040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Botker HE, Kharbanda R, Schmidt MR, Bottcher M, Kaltoft AK, Terkelsen CJ, et al. Remote ischaemic conditioning before hospital admission, as a complement to angioplasty, and effect on myocardial salvage in patients with acute myocardial infarction: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;375:727–734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hahn CD, Manlhiot C, Schmidt MR, Nielsen TT, Redington AN. Remote ischemic perconditioning: A novel therapy for acute stroke? Stroke. 2011;42:2960–2962. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.622340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ren C, Yan Z, Wei D, Gao X, Chen X, Zhao H. Limb remote ischemic postconditioning protects against focal ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2009;1288:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutherland BA, Papadakis M, Chen RL, Buchan AM. Cerebral blood flow alteration in neuroprotection following cerebral ischaemia. J Physiol. 2011;589:4105–4114. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.209601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shuaib A, Butcher K, Mohammad AA, Saqqur M, Liebeskind DS. Collateral blood vessels in acute ischaemic stroke: A potential therapeutic target. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:909–921. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atochin DN, Clark J, Demchenko IT, Moskowitz MA, Huang PL. Rapid cerebral ischemic preconditioning in mice deficient in endothelial and neuronal nitric oxide synthases. Stroke. 2003;34:1299–1303. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000066870.70976.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoyte LC, Papadakis M, Barber PA, Buchan AM. Improved regional cerebral blood flow is important for the protection seen in a mouse model of late phase ischemic preconditioning. Brain Res. 2006;1121:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hossmann KA. Pathophysiological basis of translational stroke research. Folia Neuropathol. 2009;47:213–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hossmann KA. The two pathophysiologies of focal brain ischemia: Implications for translational stroke research. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012 doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.186. Epud ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meng W, Wang X, Asahi M, Kano T, Asahi K, Ackerman RH, et al. Effects of tissue type plasminogen activator in embolic versus mechanical models of focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:1316–1321. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199912000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoda MN, Li W, Ahmad A, Ogbi S, Zemskova MA, Johnson MH, et al. Sex-independent neuroprotection with minocycline after experimental thromboembolic stroke. Exp Transl Stroke Med. 2011;3:16. doi: 10.1186/2040-7378-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Y, Fathali N, Lekic T, Ostrowski RP, Chen C, Martin RD, et al. Remote limb ischemic postconditioning protects against neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in rat pups by the opioid receptor/akt pathway. Stroke. 2011;42:439–444. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.592162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao X, Zhang H, Takahashi T, Hsieh J, Liao J, Steinberg GK, et al. The akt signaling pathway contributes to postconditioning's protection against stroke; the protection is associated with the mapk and pkc pathways. J Neurochem. 2008;105:943–955. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao H, Sapolsky RM, Steinberg GK. Interrupting reperfusion as a stroke therapy: Ischemic postconditioning reduces infarct size after focal ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1114–1121. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asahi M, Asahi K, Wang X, Lo EH. Reduction of tissue plasminogen activator-induced hemorrhage and brain injury by free radical spin trapping after embolic focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:452–457. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200003000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan X, Qiu J, Yu Z, Dai H, Singhal AB, Lo EH, et al. A rat model of studying tissue-type plasminogen activator thrombolysis in ischemic stroke with diabetes. Stroke. 2012;43:567–570. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.635250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yemisci M, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Vural A, Can A, Topalkara K, Dalkara T. Pericyte contraction induced by oxidative-nitrative stress impairs capillary reflow despite successful opening of an occluded cerebral artery. Nat Med. 2009;15:1031–1037. doi: 10.1038/nm.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gugliucci A. Human plasminogen is highly susceptible to peroxynitrite inactivation. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2003;41:1064–1068. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2003.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nielsen VG, Crow JP, Zhou F, Parks DA. Peroxynitrite inactivates tissue plasminogen activator. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1312–1317. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000111105.38836.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nanetti L, Taffi R, Vignini A, Moroni C, Raffaelli F, Bacchetti T, et al. Reactive oxygen species plasmatic levels in ischemic stroke. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;303:19–25. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taffi R, Nanetti L, Mazzanti L, Bartolini M, Vignini A, Raffaelli F, et al. Plasma levels of nitric oxide and stroke outcome. J Neurol. 2008;255:94–98. doi: 10.1007/s00415-007-0700-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinten-Johansen J, Shi W. Perconditioning and postconditioning: Current knowledge, knowledge gaps, barriers to adoption, and future directions. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2011;16:260–266. doi: 10.1177/1074248411415270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber C. Far from the heart: Receptor cross-talk in remote conditioning. Nat Med. 2010;16:760–762. doi: 10.1038/nm0710-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei D, Ren C, Chen X, Zhao H. The chronic protective effects of limb remote preconditioning and the underlying mechanisms involved in inflammatory factors in rat stroke. PloS one. 2012;7:e30892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hellberg CB, Boggs SE, Lapetina EG. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is a target for protein tyrosine nitration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;252:313–317. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fulton D, Gratton JP, McCabe TJ, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, et al. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase akt. Nature. 1999;399:597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher AM. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–605. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.