Abstract

Background

Ghrelin stimulates growth hormone (GH) secretion and regulates energy and glucose metabolism. The two circulating isoforms, acyl (AG) and desacyl (DAG) ghrelin, have distinct metabolic effects and are under active investigation for their therapeutic potentials. However, there is only limited data on the pharmacokinetics of AG and DAG.

Objectives

To evaluate key pharmacokinetic parameters of AG, DAG, and total ghrelin in healthy men and women.

Methods

In study 1 AG (1, 3 and 5 μg/kg/h) was infused over 65 min in 12 healthy (8F/4M) subjects in randomized order in. In study 2 AG (1 μg/kg/h), DAG (4 μg/kg/h), or both were infused over 210 min in 10 healthy individuals (5 F/5 M). Plasma AG and DAG were measured using specific two-site ELISAs (study1 and 2), and total ghrelin with a commercial RIA (study 1). Pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated by non-compartmental analysis.

Results

After the 1, 3 and 5 μg/kg/h doses of AG there was a dose-dependent increase in the maximum concentration (Cmax) and area under the curve [AUC(0-last)] of AG and total ghrelin. Among the different AG doses there was no difference in the elimination half-life, systemic clearance (CL), and volume of distribution. DAG had decreased CL relative to AG. The plasma DAG:AG ratio approximates 2:1 during steady state infusion of AG. Infusion of AG caused an increase of DAG, but DAG administration did not change plasma AG. Ghrelin administration did not affect plasma acylase activity.

Conclusions

The pharmacokinetics of AG and total ghrelin appear to be linear and proportional in the dose range tested. AG and DAG have very distinct metabolic fates in the circulation. There is deacylation of AG in the plasma but no evidence of acylation.

Keywords: ghrelin, pharmacokinetics, dose proportionality

Introduction

Ghrelin is a 28-amino acid peptide secreted mainly from the neuroendocrine X/A-like cells in the gastric mucosa with smaller amounts derived from the enteroendocrine cells in the proximal small intestine [1, 2] and from pancreatic islets [3, 4]. During synthesis, a significant proportion of the peptide undergoes post-translational modification in which the serine3 residue is covalently linked to a medium-chain fatty acid. This acylation process is required for the peptide to bind to its cognate receptor, the growth hormone (GH) secretagogue receptor (GHSR) 1a [1], and most biological actions ascribed to ghrelin require the activation of GHSR 1a [5]. The ghrelin isoform that has not been acylated or has had the acyl group enzymatically removed, des-acyl ghrelin (DAG), does not bind to the classical ghrelin receptor [1] but a variety of GHSR-1a independent effects on insulin secretion [6], osteoblast growth [7], and lipid metabolism in adipocytes [8], have been attributed to it. Given that there are “antidiabetic” properties of DAG as opposed to the “prodiabetic” effects of AG observed in preclinical and clinical studies, DAG analogues have been developed recently and their potential as therapeutics for type 2 diabetes is being investigated [9]. Acylation of ghrelin is a specific process primarily mediated by the recently discovered enzyme ghrelin O-acyl transferase (GOAT) [10, 11]. It is unclear what percentage of ghrelin is acylated intracellularly, but both AG and DAG are detectable in the circulation where they exist in reported ratios of 1:4 to 1:9 depending on the sample preservation methods, assay, species, or nutritional state, with the AG being the less common species [1, 12].

Ghrelin is the only known circulating factor that promotes food intake. In healthy subjects, plasma ghrelin levels rise progressively before meals and fall to a nadir within two hours after eating, with changes in plasma levels during meals that vary 2- to 4-fold [12, 13]. Interestingly, total ghrelin levels do not increase significantly after long-term food deprivation, but the two isoforms follow distinct patterns: DAG remains at peak pre-fasting levels while AG concentrations settle near what is the usual nadir following a typical meal [12]. Consistent with these changes in plasma ghrelin isoforms, expression of GOAT mRNA decreases in the stomach of fasting mice [14]. These observations suggest that ghrelin secretion and acylation are processes that may be separately regulated. Detailed information about ghrelin elimination in healthy individuals is limited. Substantial hepatic extraction of AG has been reported [15], but it is not clear whether deacylation takes place primarily in the liver. In contrast there is some evidence that renal clearance may be a major pathway for the clearance of DAG [16, 17] typical for the clearance of small peptides. In additional to hepatic and renal elimination, AG is deacylated to DAG by serum and tissue esterases such as butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) [18]. It is unclear whether exogenous ghrelin administration alters the deacylation process in humans.

Given many of the observed opposing metabolic effects of AG and DAG and suggestion of different routes of elimination, it is important to understand the metabolism of these two isoforms and their pharmacokinetic properties when designing physiology or pharmacology studies for clinical research. The objective of the present study was to determine basic pharmacokinetic parameters of AG and DAG in healthy individuals with normal liver and kidney function. We focused on the relation of ghrelin dose to change plasma levels and systemic exposure as measured by area under the plasma concentration curve (AUC) and peak plasma levels (Cmax). We also examined the dynamic changes in AG and DAG concentration during continuous AG, DAG or combined AG and DAG infusions in a separate study of 10 healthy subjects. Finally we assessed the effects of AG infusion on the serum activity of the ghrelin deacylation enzyme BuChE.

Methods

Study Design: Study 1

This was a randomized, single-blinded study designed to examine the effect of ghrelin on insulin secretion and glucose tolerance in healthy subjects [19]. Briefly, healthy volunteers between the ages of 18 and 55 with a BMI between 18 and 29 kg/m2 were recruited from the greater Cincinnati area. Subjects with a history or clinical evidence of impaired fasting glucose or diabetes mellitus, recent myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, active liver or kidney disease, GH deficiency or excess, neuroendocrine tumor, anemia or who were on medications known to alter insulin sensitivity were excluded. Study procedures were performed at the Cincinnati Children’s Medical Center Clinical and Translational Research Center (CTRC). All study participants signed informed consent documents that had been approved by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Review Board.

After a 10-12 hour fast, either synthetic human AG (Bachem AG, Rubendorf, Switzerland) at doses of 1, 3, and 5 μg/kg/h or 0.9% saline was infused for a total of 65 min on 4 separate days. An IV bolus of glucose (11.4 g/m2 body surface area) was given at 55 min as part of the IV glucose tolerance test (IVGTT) to assess acute insulin response to IV glucose. After ghrelin infusion was stopped at 65 min, 7 additional blood samples were taken at 2-5 min intervals for 20 min to measure ghrelin clearance rate. Blood samples were stored on ice and plasma separated by centrifugation within an hour. The plasma samples were stored at −80° C until further analysis.

Study 2

Subjects: Healthy volunteers, similar to those in study 1, between the ages of 18 and 50 years with a BMI between 18 and 29 kg/m2 were recruited from the greater Cincinnati area. All study participants signed informed consent documents that had been approved by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Review Board.

Subjects received a) synthetic human AG (Bachem Americas, CA; 0.28 μg/kg bolus followed by 1 μg/kg/h rate of infusion), b) human DAG (C S Bio Co., CA; 1.1 μg/kg bolus followed by 4 μg/kg/h continuous infusion), c) a combined infusion of AG and DAG (same rate as single infusions), d) or saline for a total of 210 min on 4 separate study days in randomized order. A frequently sampled IV glucose tolerance test (FSIVGTT) designed to quantify insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity began 30 min after the infusions were started and continued for 180 min. Ghrelin measurements were obtained at 0, 5, 15, 25, 30, 60, 90, 150, and 210 min during the infusion period.

Studies 1 & 2

Sample Analyses

Blood samples were collected into 3 ml EDTA-plasma tubes containing 0.06 ml AEBSF, a protease and esterase inhibitor (4 mM final concentration). Following centrifugation, 200 μL 1 N HCl was added to every milliliter of plasma. Plasma total immunoreactive ghrelin was measured by radioimmunoassay (RIA) using a commercially available kit (Millipore, MA). Lower and upper limits of detection were 40 and 2560 pg/ml with intra- and inter-assay CVs of 4 and 14.7%, respectively. AG and DAG levels were measured using separate sensitive and specific two-site sandwich ELISAs. The sensitivity of the AG assay was 6.7 pg/ml with an intra- and inter-assay CVs of ~ 14 and 18% [12]. The sensitivity of the DAG assay was 4.6 pg/ml with an intra- and inter-assay CVs of ~ 13 and 20 % [12]. BuChE activity was determined by colorimetric assay following established methods [20]. Assay results are reported as enzyme units relative to the activity of a purified bovine BuChE standard (Sigma-Aldrich #C1057) run on each plate. The assay showed an intra-assay CV of 3.6% and an inter-assay CV of 7.2%. All samples were run in duplicates, and all specimens froma given participant were run in the same assay.

Pharmacokinetic Analysis

The pharmacokinetic data were analyzed with the non-compartmental model using WinNonlin 6.2 (Pharsight Inc.). Peak plasma levels (Cmax), time required to achieve Cmax (Tmax), mean residence time (MRT), and volume of distribution (Vd) were estimated [21]. The elimination half-life (t1/2) of ghrelin was calculated as the ratio of Ln2/λz (λz, slope of the terminal portion of the concentration vs. time curve after the termination of ghrelin infusion). AUC0-last was computed using the linear trapezoidal rule. Average of the two plasma ghrelin levels prior to ghrelin or saline administration served as baseline. Systemic clearance (CL) was estimated by Dose/AUC0-last.

Statistical analysis

All pharmacokinetic estimates are expressed as mean ± SD. Dose proportionality in Cmax and AUC were assessed using both linear regression and power law. Pharmacokinetic parameters between low and high ghrelin doses were compared using a paired student t test. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to compare parameters across the three ghrelin doses. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software).

Results

Subject characteristics

Subject characteristics for Study 1 were described in detail elsewhere [19]. In brief, 12 healthy men and women (8M/4F) with an average age of 26.0 ± 11.4 years [mean ± SD] and BMI of 24.1 ± 4.2 kg/m2 completed the study. In Study 2, 17 subjects (9 M/8 F) completed the study. AG and DAG measures were obtained in 10 of the 17 subjects (5 F/5 M, age 25.9 ± 6.1 years, BMI 24.5 ± 3.4 kg/m2).

Plasma concentrations of ghrelin during infusions

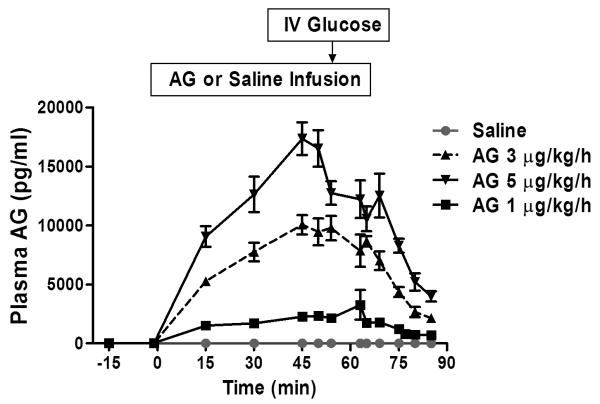

In Study 1, infusions of AG at 1, 3, and 5 μg/kg/h raised plasma concentrations of AG to peak concentrations of 3.9 ± 3.5, 11.7 ± 2.4, and 19.6 ± 2.3 ng/mL, corresponding to a 118-, 355- and 594-fold increases from the mean baseline AG concentrations of 0.033 ± 0.024 ng/mL, respectively. A plasma steady state was reached at 45 minutes after the start of ghrelin infusion. Overall, the mean plasma concentration of AG demonstrated a dose-response increase during the continuous IV infusion (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Plasma AG and DAG ghrelin levels during varying doses of AG infusion in healthy men and women. a). Plasma acyl ghrelin (AG) levels after 1, 3, and 5 μg/kg/h doses of AG or saline continuous IV infusion (0 to 65 minutes) in healthy men and women in study 1. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

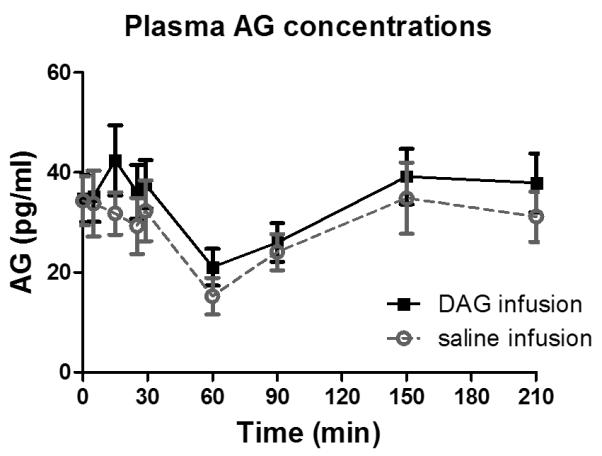

In Study 2 (Figure 2 a-d), the 1 μg/kg/h AG infusion raised plasma AG concentrations from 0.043 ± 0.038 ng/ml to 1.93 ± 1.30 ng/ml and DAG concentrations from 0.078 ± 0.045 ng/ml to 1.29 ± 1.12 ng/ml, respectively, corresponding to a 44- and 17-fold increase from baseline. Conversely, the 4 μg/kg/h DAG infusion exclusively increased plasma DAG levels (from 0.068 ± 0.044 ng/ml to 15.9 ± 4.91 ng/ml) corresponding to a 233-fold rise. AG levels did not change with administration of DAG (baseline 0.036 ± 0.014 ng/ml to 0.050 ± 0.021 ng/ml), and in fact, were similar to those during the saline infusion (Figure 3). The combined AG and DAG infusions raised plasma AG 54 fold, and DAG concentrations 272 fold, changes of similar magnitude to the individual infusions.

Figure 2.

Plasma AG and DAG concentrations during IV AG and DAG infusions in healthy men and women (n of 10) in Study 2. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 3.

Relationships of observed Cmax and AUC(0-∞) values for acyl ghrelin (AG) and total ghrelin versus AG infusion dose with linear regression (bold line), and the 95% confidence interval (dashed line).

The DAG:AG ratio was 1.85 ± 0.07 at baseline and did not change during the saline infusion (DAG AUC0-last : AG AUC0-last = 1.90 ± 0.50), remaining constant during the entire FSIVGTT (Table 2, Figure 2a). The 1 μg/kg/h AG infusion reversed the DAG:AG ratio to 0.4:1 (DAG AUC0-last : AG AUC0-last = 0.6 ± 0.3; Table 2, Figure 2b), and although DAG increased significantly with the AG infusion, levels remained lower than AG during the entire 210-minutes. DAG was the predominant plasma isoform with the combined AG and DAG infusion (Figure 2d).

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameter estimates of plasma AG and DAG after administration of varying doses of AG or DAG or the combination of AG and DAG by continuous IV infusion in healthy men and women obtained by non-compartmental analysis. Results are presented as Mean ± SD

| Saline Infusion |

AG Infusion (1 μg/kg/h) |

DAG Infusion (4 μg/kg/h) |

AG + DAG Infusion (1+4 μg/kg/h) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacokinetic parameters of AG | ||||

| Tmax (min) | 148 ± 89 | 65 ± 66 | 101 ± 63 | |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 0.045 ± 0.02 | 1.93 ± 1.30 | 0.05 ±a 0.021 | 1.65 ± 0.63 |

|

AUC(0-last) (min*ng/mL) |

5.67 ± 3.10 | 267.86 ± 180.83 |

7.7 ± 1.88 | 253.57 ± 90.86 |

| MRT (min) | 107 ± 11 | 108 ± 10 | 106 ± 8 | 107 ± 7 |

| CL (mL/min/kg) | 5.4 ± 2.8 | 4.5 ± 2.0 | ||

| Pharmacokinetic parameters of DAG | ||||

| Tmax (min) | 109 ± 74 | 170 ± 49 | 175 ± 32 | |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 0.078 ± 0.03 | 1.29 ± 1.12 | 15.94 ± 4.91 | 15.48 ± 3.6 |

|

AUC(0-last) (min*ng/mL) |

11.04 ± 5.05 | 172.35 ± 132.2 |

2696.53 ± 953.3 |

2556.56 ± 714.6 |

| MRT (min) | 107 ± 10 | 107 ± 11 | 106 ± 8 | 110 ± 9 |

| CL (mL/min/kg) | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | ||

Pharmacokinetics of AG and DAG

The pharmacokinetic estimates of AG and total ghrelin for Study 1 as determined by the non-compartmental analysis are summarized in Table 1. The mean t1/2 of AG was in the range of 9-11 minutes. The Cmax achieved with the 3 and 5 μg/kg/h dose AG infusions was approximately 3 and 5 times that with the 1μg/kg/h dose, respectively. AUC0-last also increased linearly with dose, and like Cmax, demonstrated a dose-proportional change. The observed differences in Cmax and AUC0-last were abolished when the measures were normalized to dose for AG. The MRT, CL and the steady-state Vd were similar between the three doses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameter estimates of plasma acyl and total ghrelin after administration of 1, 3, and 5 μg/kg/h dose acyl ghrelin (AG) continuous IV infusion (study 1) in healthy men and women obtained by non-compartmental analysis. Results are presented as mean ± SD.

| ACYL GHRELIN | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AG Infusion Dose | |||

| Parameter | 1 μg/kg/h | 3 μg/kg/h | 5 μg/kg/h |

| Half-life (min) | 11 ± 4 | 10 ± 3 | 9 ± 2 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 3.87 ± 3.46 | 11.72 ± 2.39 | 19.64 ± 2.34 |

| Cmax/D | 3.87 ± 3.46 | 3.91 ± 0.79 | 3.92 ± 0.47 |

| AUC(0-90) (min*ng/mL) | 142 ± 47 | 549 ± 100 | 896 ± 174 |

| AUC(0-90)/D | 142 ± 47 | 183 ± 33 | 179 ± 35 |

| MRT (min) | 45 ± 3 | 45 ± 2 | 45 ± 2 |

| CL (mL/min/kg) | 7.66 ± 2.36 | 5.73 ± 0.91 | 5.47 ± 0.69 |

| Vd (mL/kg) | 126 ± 58 | 79 ± 24 | 78 ± 22 |

| TOTAL GHRELIN | |||

| AG Infusion Dose | |||

| Parameter | 1 μg/kg/h | 3 μg/kg/h | 5 μg/kg/h |

| Half-life (min) | 39 ± 17 | 32 ± 10 | 34 ± 13 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 5.49 ± 0.61 | 17.13 ± 4.5 | 28.73 ±11.59 |

|

AUC(0-90)

(min*ng/mL) |

323 ± 61 | 955 ± 202 | 1550 ± 492 |

| AUC(0-90) /D | 323 ± 61 | 318 ± 67 | 310 ± 98 |

| MRT (min) | 85 ± 19 | 91 ± 49 | 47 ± 14 |

| CL (mL/min/kg) | 2.27 ± 1.003 | 2.26 ± 0.77 | 2.48 ± 0.71 |

| Vd (mL/kg) | 114 ± 21 | 127 ± 56 | 119 ± 65 |

Plasma total ghrelin concentrations during AG infusion were reported previously [19]. A summary of the pharmacokinetic properties of total ghrelin is shown in Table 1. In comparison to AG, total ghrelin had a longer t1/2 of approximately 35 minutes. Consistent with the findings for AG, Cmax for total ghrelin increased proportionally with higher doses of AG infusion (5.49 ± 0.61, 17.13 ± 4.50, 28.73 ± 11.59 ng/mL, from low to high, respectively). Similarly, the AUC0–last for total ghrelin during AG infusions were 531.9 ± 155.0, 1583.1 ± 574.8, and 2326.1 ± 587.9 min*ng/mL, from low to high doses respectively. There was no significant difference in MRT, CL or Vd between the three doses (Table 1).

The relationship between dose and plasma total ghrelin and AG concentrations were examined using linear regression analysis. Both plasma AG and total ghrelin Cmax and AUC increased linearly with increase doses of AG administration (R2 = 0.86 and 0.94 for AG, Figure 3a, b; R2 = 0.66 and 0.72 for total ghrelin, Figure 3c, d, respectively) whereas the dose-adjusted Cmax (Cmax/D) and AUC0–last (AUC0–last/D) remained constant (Table 1).

BuChE is the enzyme that accounts for the majority of deacylation of AG in the circulation of humans [18]. Plasma BuChE activity was measured during saline and ghrelin infusion in 6 subjects at 0, 44 and 65 min into the AG infusion. Neither infusion time nor treatment assignment affected plasma BuChE levels (p = 0.95, 2-way repeated measures ANOVA), suggesting that neither the exogenous AG infusion nor the dose of AG altered the ghrelin desacylation process.

Study 2

The pharmacokinetic estimates of AG and DAG obtained by non-compartmental analysis are summarized in Table 2. Both Cmax and AUC0-last for AG and DAG in the plasma increased during the 1 μg/kg/h AG infusion, while the DAG infusion only increased Cmax and AUC0-last for DAG. MRTs were similar across all infusions. The systemic CL was similar between single-peptide and combined-peptide (AG + DAG) infusions but the CL of DAG was ~3 times smaller than AG when they were infused alone (Table 2). Unlike study 1, a direct measure of AG or DAG t1/2 could not be achieved because ghrelin was infused at a constant rate till the end of the study.

DISCUSSION

Recent experimental findings indicate that ghrelin plays an important role in the regulation of energy balance and glucose metabolism [22]. The available information suggests that the two ghrelin isoforms, AG and DAG have distinct metabolic effects [23], and analogues of both compounds are being developed for potential therapeutic application [9, 24]. Despite the accumulation of evidence supporting physiologic roles for ghrelin little is known about its metabolism and clearance. In this study, we analyzed data from studies with AG and DAG infusions to determine pharmacokinetic parameters for the two isoforms in healthy, non-obese individuals with normal liver and kidney function. Our findings suggest that AG and DAG have different metabolic fates in the circulation with distinct rates of clearance. Moreover, the results presented here indicate that AG is actively deacylated in the plasma.

In study 1, the wide range of ghrelin doses and frequent measures of AG and DAG allowed us to examine the dose proportionality of IV ghrelin administration. Relative to the 1μg/kg/h dose, the Cmax for AG resulting from the 3 and 5 μg/kg/h dose infusions increased by 3- and 5-fold while AUC increased by 4- and 6-fold, respectively. Consistent with this, the dose-normalized Cmax and AUC values were not different between doses (Table 1). These observations demonstrate a clear and strong linear relationship between plasma AG concentration and treatment dose (Figure 2 a, b). In keeping with the dose-proportionality of the pharmacokinetics, the elimination characteristics of AG, as reflected in the t1/2, MRT, systemic CL, and Vd were largely unchanged with different administration rates (Table 1). Thus, our findings demonstrate that, for AG, the increase in plasma levels can be reliably predicted based on the observed linear relationship for the dose range of 1 – 5 μg/kg/h. A similar positive linear relationship was also observed between total ghrelin Cmax, AUC and AG dose (Figure 2 c, d) [25]. Of note, the Cmax, MRT, and CL estimates were quite different for comparable AG doses in study 1 and 2 (Table 1 and 2). The ghrelin ELISA platform was changed between study 1 and 2 to improve assay sensitivity (these assays have very different specificity). This could partially explain the difference of PK parameters between the two studies. Differences in subject characteristics (i.e. body weight) between the two studies could also contribute to the pharmacokinetic variances. However, the fold-increase of Cmax and AUC from saline to 1 μg/kg/hr dose ghrelin infusion was quite similar between studies.

Since the majority of the studies using exogenous ghrelin administer AG, the pharmacokinetics reported here provide some guidance for the appropriate dose and route of administration for further research. In addition to the novel observation of a dose-proportionality, our findings on other pharmacokinetic parameters for ghrelin are consistent with those reported previously. For example, the first-order elimination t1/2 we determined using non-compartmental analysis were 9-11 min for AG and 30-34 min for total ghrelin using doses ranging from 1-5 μg/kg/h. This is comparable to the findings of Akamizu et al. who reported a t1/2 of 9-13 min for AG and 27-31 min for total ghrelin following ghrelin bolus injections 1 and 5 μg/kg using a one-compartment model analysis [26]. Vestergaard et al. employed a two-compartmental model to describe the pharmacokinetics of total ghrelin following administration of AG using a dose of 5 pmol/kg/min (equivalent to 1 μg/kg/h) for 180 min [27]. Their observed pharmacokinetic parameters for total ghrelin (Cmax of 4.41 ± 0.29 μg/L, initial t1/2 of 24.2 ± 2.5 min, MRT of 92.7 ± 16.3 min) are in general agreement to the ones we report here. Likewise, the results of Paulo et al. [28] of a mean t1/2 of 36 ± 2.4 min for total ghrelin estimated from the 1 μg/kg AG injection is very similar to our estimates. However, their t1/2 for AG of 21 ± 3.0 min is longer than our estimate of 11 ± 4 min. In contrast to our observations, the metabolic CL and the t1/2 of AG and total ghrelin were reported to be increasing with higher doses of ghrelin in that study. If these results are accurate, it would suggest that the clearance/inactivation of AG is non-linear and concentration-dependent. Differences in study design, study population, and assay methods are likely to explain the apparent discrepancy between our findings and those from Paulo et al.

DAG does not bind to the GHSR-1a and its biological role has been questioned since no cognate receptor has been identified [1]. Some investigators have reported that DAG can exert beneficial effects on insulin secretion and glucose tolerance that, in general, tend to be opposite those of AG [29-31]. DAG analogues are being developed as therapeutic agents for metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes [9]. However, the pharmacokinetics of synthetic human DAG has not been well characterized. We found that when AG (1 μg/kg/h) alone was infused, both plasma AG and DAG levels increased significantly showing a 47- and 16-fold increase in Cmax from baseline, respectively. Conversely, the DAG (4 μg/kg/h) alone infusion preferentially increased DAG concentration in the circulation without altering the levels of AG relative to saline infusion. (Figures 2 a-c). These findings are consistent with observations made by Vestergaard et al. [32] and suggest that AG is metabolized to DAG in peripheral circulation while little acylation of exogenous DAG is occurring. The combined AG and DAG infusion raised plasma levels of AG and DAG to the same extent as that observed with individual administration. The pharmacokinetic parameters such as CL and Vd of both AG and DAG were similar whether giving as single agents or in combination.

It is not known what percentage of the ghrelin is acylated when secreted from ghrelin producing cells. Both duration of fasting and dietary medium chain fatty acid composition can impact ghrelin acylation [12, 14]. Using a highly sensitive and specific two-site sandwich assay to measure AG and DAG, we found that DAG:AG ratio was 1.8 ± 0.7 at baseline (after an overnight fast) and 1.9 ± 0.5 during saline infusion (DAG AUC0-last : AG AUC0-last). This ratio remained quite constant during the FSIVGTT (Figure 2a), and is consistent with a previous report by Liu et al. using the same ghrelin assay [25]. Following AG infusion, plasma concentrations of both AG and DAG increased substantially but the ratio of DAG:AG in plasma remained constant during the infusion period (Figure 2b-c). This would suggest that in addition to the production of “new” DAG from AG breakdown, DAG elimination was also increased in proportion to load resulting in a steady state with a constant DAG:AG ratio. Data on the route of elimination of ghrelin is limited and seems to differ for the two isoforms as AG is extracted substantially by the liver [15, 33] while DAG appears to undergo significant renal clearance [16, 17]. Several enzymes have been identified as responsible for the removal of the octanoyl group from the AG peptide. BuChE is the main deacylating enzyme in humans [18]. In our study, BuChE activity was not altered by AG infusion. We did not measure renal clearance of ghrelin in this study.

Even though the t1/2 could not be directly determined in study 2 due to the study design (bolus injection followed by continuous infusion), the observed difference between the clearance of these compounds (DAG 1.7 ± 0.9 vs. AG 5.4 ± 2.8 mL/min/kg, Table 2) suggest that the half-life of DAG is approximately 3-fold longer than that of AG assuming that other parameters such as Vd between AG and DAG are similar. This may be the primary factor contributing to the observed longer t1/2 of total ghrelin. In all likelihood the t1/2 of DAG reflects clearance of the peptide from the circulation, while the much shorter t1/2 of AG is principally due to deacylation in the circulation and conversion to DAG. In fact the conversion of AG to DAG is relatively slow compared to other regulatory peptides that are metabolized intravascularly such as glucose dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) [34] and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) [35]. Moreover, the clearance of DAG is also slower than peptides like insulin and glucagon [36]. Thus, based on our analyses the ghrelin isoforms are relatively long-lived in the circulation, which may have implications for their biologic effects.

In conclusion, the present study is the first to examine the proportionality of pharmacokinetic parameters of AG and total ghrelin in healthy humans. The pharmacokinetics parameters of AG reported in the present study provided useful information for investigators who conduct clinical research on ghrelin physiology or pharmacology. This understanding is important as both AG and DAG appear to have therapeutic properties and are currently being investigated in the clinical setting for pharmacological activity.

Figure 4.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research is provided by NIH/NIDDK (5K23DK80081 to J.T.) and supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant 8 UL1 TR000077-04. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We want to thank the CTRC nursing staff at Cincinnati Children’s Medical Center and the Cincinnati Veterans Affairs Medical Center for their excellent support for the study.

Research funding: JT - NIH/NIDDK (5K23DK80081, 1R03DK89090)

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: the authors have no potential conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERENCE

- 1.Kojima M, et al. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402(6762):656–60. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Date Y, et al. Ghrelin, a novel growth hormone-releasing acylated peptide, is synthesized in a distinct endocrine cell type in the gastrointestinal tracts of rats and humans. Endocrinology. 2000;141(11):4255–61. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.11.7757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wierup N, et al. The ghrelin cell: a novel developmentally regulated islet cell in the human pancreas. Regul Pept. 2002;107(1-3):63–9. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andralojc KM, et al. Ghrelin-producing epsilon cells in the developing and adult human pancreas. Diabetologia. 2009;52(3):486–93. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1238-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Lely AJ, et al. Biological, physiological, pathophysiological, and pharmacological aspects of ghrelin. Endocr Rev. 2004;25(3):426–57. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gauna C, et al. Unacylated ghrelin is active on the INS-1E rat insulinoma cell line independently of the growth hormone secretagogue receptor type 1a and the corticotropin releasing factor 2 receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;251(1-2):103–11. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delhanty PJ, et al. Ghrelin and unacylated ghrelin stimulate human osteoblast growth via mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathways in the absence of GHS-R1a. J Endocrinol. 2006;188(1):37–47. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muccioli G, et al. Ghrelin and des-acyl ghrelin both inhibit isoproterenol-induced lipolysis in rat adipocytes via a non-type 1a growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;498(1-3):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Julien M, et al. In vitro and in vivo stability and pharmacokinetic profile of unacylated ghrelin (UAG) analogues. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2012;47(4):625–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang J, et al. Identification of the acyltransferase that octanoylates ghrelin, an appetite-stimulating peptide hormone. Cell. 2008;132(3):387–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutierrez JA, et al. Ghrelin octanoylation mediated by an orphan lipid transferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(17):6320–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800708105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, et al. Novel ghrelin assays provide evidence for independent regulation of ghrelin acylation and secretion in healthy young men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1980–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummings DE, et al. A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes. 2001;50(8):1714–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirchner H, et al. GOAT links dietary lipids with the endocrine control of energy balance. Nat Med. 2009;15(7):741–5. doi: 10.1038/nm.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banks WA, Burney BO, Robinson SM. Effects of triglycerides, obesity, and starvation on ghrelin transport across the blood-brain barrier. Peptides. 2008;29(11):2061–5. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshimoto A, et al. Plasma ghrelin and desacyl ghrelin concentrations in renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(11):2748–52. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000032420.12455.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarkovska Z, et al. Plasma levels of active and total ghrelin in renal failure: a relationship with GH/IGF-I axis. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2005;15(6):369–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Vriese C, et al. Ghrelin degradation by serum and tissue homogenates: identification of the cleavage sites. Endocrinology. 2004;145(11):4997–5005. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong J, et al. Ghrelin Suppresses Glucose-stimulated Insulin Secretion and Deteriorates Glucose Tolerance in Healthy Humans. Diabetes. 2010 doi: 10.2337/db10-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellman GL, et al. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller EE, et al. GH-related and extra-endocrine actions of GH secretagogues in aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23(5):907–19. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castaneda TR, et al. Ghrelin in the regulation of body weight and metabolism. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2010;31(1):44–60. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heppner KM, et al. The ghrelin O-acyltransferase-ghrelin system: a novel regulator of glucose metabolism. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2011;18(1):50–5. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e328341e1d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller TD, et al. Ghrelin and its potential in the treatment of eating/wasting disorders and cachexia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2010;1(2):159–167. doi: 10.1007/s13539-010-0012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J, et al. Novel Ghrelin Assays Provide Evidence for Independent Regulation of Ghrelin Acylation and Secretion in Healthy Young Men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akamizu T, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and endocrine and appetite effects of ghrelin administration in young healthy subjects. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150(4):447–55. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1500447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vestergaard ET, et al. Constant intravenous ghrelin infusion in healthy young men: clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolic effects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292(6):E1829–36. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00682.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paulo RC, et al. Estrogen elevates the peak overnight production rate of acylated ghrelin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11):4440–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Broglio F, et al. Non-acylated ghrelin counteracts the metabolic but not the neuroendocrine response to acylated ghrelin in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):3062–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gauna C, et al. Administration of acylated ghrelin reduces insulin sensitivity, whereas the combination of acylated plus unacylated ghrelin strongly improves insulin sensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(10):5035–42. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiewiet R, et al. Effects of acute administration of acylated and unacylated ghrelin on glucose and insulin concentrations in morbidly obese subjects without overt diabetes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009 doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vestergaard ET, et al. Acute peripheral metabolic effects of intraarterial ghrelin infusion in healthy young men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(2):468–77. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gauna C, et al. Intravenous glucose administration in fasting rats has differential effects on acylated and unacylated ghrelin in the portal and systemic circulation: a comparison between portal and peripheral concentrations in anesthetized rats. Endocrinology. 2007;148(11):5278–87. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kieffer TJ, McIntosh CH, Pederson RA. Degradation of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and truncated glucagon-like peptide 1 in vitro and in vivo by dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Endocrinology. 1995;136(8):3585–96. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.8.7628397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drucker DJ. The biology of incretin hormones. Cell Metab. 2006;3(3):153–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams RF, Gleason RE, Soeldner JS. The half-life of endogenous serum immunoreactive insulin in man. Metabolism. 1968;17(11):1025–9. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(68)90009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]