Abstract

Background

We developed RA risk models based on validated environmental factors (E), genetic risk scores (GRS), and gene-environment interactions (GEI) to identify factors that can improve accuracy and reclassification.

Methods

Models including E, GRS, GEI were developed among 317 Caucasian seropositive RA cases and 551 controls from Nurses’ Health Studies (NHS) and validated in 987 Caucasian ACPA positive cases and 958 controls from the Swedish Epidemiologic Investigation of RA (EIRA), stratified by gender. Primary analyses included age, smoking, alcohol, parity, weighted GRS using 31 non-HLA alleles, 8 HLA-DRB1 alleles and HLA X smoking interaction. Expanded models included reproductive, geographic, and occupational factors, and additional GEI terms. Hierarchical models were compared for discriminative accuracy using AUC and reclassification using Integrated Discrimination Improvement (IDI) and continuous Net Reclassification Index.

Results

Mean (SD) age of RA diagnosis was 57 in NHS and 50 in EIRA. Primary models produced an AUC of 0.716 in NHS, 0.728 in EIRA women and 0.756 in EIRA men. Expanded models produced improvements in discrimination with AUCs of 0.738 in NHS, 0.728 in EIRA women and 0.769 in EIRA men. Models including G or G + GEI improved reclassification over E models; the full E+G+GEI model provided the optimal predictive ability by IDI analyses.

Conclusions

We have developed comprehensive RA risk models incorporating epidemiologic and genetic factors and gene-environment interactions that have improved discriminative accuracy for RA. Further work developing and assessing highly specific prediction models in prospective cohorts is still needed to inform primary RA prevention trials.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), an autoimmune disease that causes inflammatory and disabling arthritis, is thought to develop in individuals with inherited genetic risk factors after exposure to environmental factors, including cigarette smoking, residential history, air pollution, occupational exposures, alcohol, female reproductive factors, and low socioeconomic status1-31. The identification of risk alleles for RA through genome-wide association studies and meta-analyses, along with the discovery of gene-environment interactions, could potentially allow the prediction of RA risk among individuals without symptoms2, 32-42. The Framingham Risk Score43 was developed with the specific goal of clinical risk prediction aiding clinicians in making both recommendations about risk factor modification and decisions about preventive treatment. This successful paradigm of individualized risk factor assessment and stratification has led to a reduction of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality worldwide44, 45. Efforts are now underway to develop similar predictive models for the early identification of individuals at high risk of developing RA among asymptomatic populations who could be enrolled in primary prevention trials 46. The first step in this process is to determine the optimal variables to include in such models.

The goal of this study was to develop a risk model based on epidemiologic factors that can be collected easily at a clinical visit, and to study the benefit of adding genetic and gene-environment interaction terms to the model. We used novel statistical methods to choose the optimal combination of predictors among epidemiological factors, genetic susceptibility alleles, and gene-environment interactions for training and validation in an independent dataset. Our hypothesis is that models including G and GEI terms will have the optimal predictive accuracy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population

NHS

We conducted a nested case-control study of RA susceptibility among the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) prospective cohorts. Among 121,700 female nurses aged 30 to 55 years in NHS, 32,826 (27%) participants provided blood samples and another 33,040 (27%) provided buccal cell samples. Of 116,609 female nurses aged 25 to 42 years in NHSII, 29,611 (25%) provided blood samples. The two cohorts were combined in this manuscript and are referred to as ‘NHS’. Incident RA cases in NHS were confirmed using a two-stage screening method with a connective tissue disease screening questionnaire (CSQ) for RA symptoms47 and confirmed by chart review by two board-certified rheumatologists. Rheumatoid factor (RF) was determined by chart review and anti-citrullinated antibodies (ACPA) status was determined by chart review and/or direct assay for RA cases with banked plasma samples from prior to diagnosis48. For each confirmed RA case, a healthy control was chosen, matched on cohort (NHS/NHSII), year of birth, menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone use. There were 585 women with validated RA who provided blood samples, 21 (4%) cases were excluded for non-self-reported Caucasian and an additional 22 (4%) were excluded due to missing HLA information. For anyone missing other SNPs, we assigned them a value equal to the expected value (2*risk allele frequency defined in cases or controls separately). Finally, since prior genetic association studies focused on seropositive RA39, analyses were limited to seropositive RA cases (n=317) compared to healthy controls (n=551).

EIRA

The Epidemiologic Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis (EIRA) is a population based case-control study which enrolled newly diagnosed cases of RA in Sweden aged 18-70 years between May 1996 and December 2009. Controls were randomly selected, matched to cases on age, sex and geographic location7, 40. A total of 987 anti-citrullinated protein antibodies positive (ACPA+) cases, (702 women and 285 men) and 958 controls (715 women and 243 men) with information on the 31 non-HLA loci and the HLA alleles were used for analyses. In EIRA, a total of 1218 ACPA positive RA cases and 1129 controls recruited from May 1996 to the end of 2009 were selected for genome-wide genotyping. After sample quality control (sample genotype call rate>0.95, ethnicity outliers removed), 988 citrullinated protein antibodies positive (ACPA+) cases (81%) and 958 (85%) controls remained. One male case with 3 HLA alleles was further removed from the analyses. A final dataset with 987 cases (702 women and 285 men) and 958 controls (715 women and 243 men) with information on the 31 non-HLA loci and the HLA alleles was used for analyses.

All aspects of these studies were approved by Partners’ HealthCare or the Karolinska Institutet Institutional Review Boards.

Epidemiologic Factors

We selected epidemiologic factors that had been demonstrated in the literature by other groups and replicated in our datasets to be significantly associated with RA susceptibility including age, smoking, alcohol, education and parity (in women only), and could be easily ascertained in clinical practice3, 4, 8, 9, 16, 18, 19, 24, 30, 31, 49. In the primary analysis, we only included factors that were available in both cohorts and not discovered in either NHS or EIRA. For a secondary analysis we also explored expanded models that also considered risk factors first published by our groups including additional reproductive factors, geographic region, and occupational exposures (in men only)10, 11, 14, 15, 24, as well as gene-environment interactions (GEI) for GST and HMOX1 genes42.

NHS

Epidemiologic factors for the primary models in NHS included year of birth, smoking (pack-years), alcohol consumption (cumulative average of daily intake), husband’s educational attainment (as a marker of socioeconomic status) and parity (for females). For expanded NHS models we included region of residence at age 30, age at menarche, menstrual regularity, breastfeeding, oral contraceptive use, menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone use10, 24. All epidemiologic variables were updated through the biennial questionnaire before RA diagnosis (or index date for controls).

EIRA

Epidemiologic factors for the primary models in EIRA included year of birth, smoking exposure before disease onset (pack-years), alcohol consumption, education level (as a marker of socioeconomic status) and parity (for females). For expanded models in EIRA males, we also included occupational exposure to silica, mineral oil and solvents, and HLA-SE X exposure interaction terms14, 15. All data were collected from subjects at the time of incident RA and pertained to exposures prior to RA onset.

Genetic Factors

Genetic Risk Score (GRS)

Thirty-nine validated risk alleles for RA were combined to form a continuous GRS, a weighted combination of 8 HLA-DRB1 ‘shared epitope’ (HLA-SE) alleles and 31 non-HLA risk alleles (GRS39), weighted by the natural log of the published OR50 (Supplemental Table 1). To assess the independent contribution of the HLA-SE alleles, we created a GRS limited to only the non-HLA-SE alleles (GRS31). Genotyping and quality control procedures for both NHS and EIRA are described in detail elsewhere2, 37, 41, 42.

Other genetic factors

GSTT-1 homozygous deletion (GSTT1 null) and HMOX-1 variants, GSTT1 X smoking, HMOX1 X smoking interaction terms were included in the expanded models as both were found to significantly interact with smoking and RA risk in the NHS, with replication of the GSTT1-smoking interaction in EIRA42.

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression models were used to estimate the predicted odds of seropositive or ACPA+ RA. GEI was modeled on a multiplicative scale using a product term (GxE). Analyses were performed in accordance with the 25 recommendations for evaluations of risk prediction models (GRIPS Statement)51.

Model building

The lists of all variables and interactions considered for inclusion are summarized in Table 1 in two categories described as 1)’primary’ variables available in both NHS and EIRA and 2) ‘expanded’ variables available in either NHS or EIRA cohorts. NHS was used as the primary dataset to determine the optimal combination of variables. EIRA was not used as the primary dataset since many of the genetic risk alleles and the HLA*smoking interaction were discovered in this study and could have led to overfitting of the models. Variables were selected based on contribution to the overall model prediction based on the IDI (described below). The final list of variables included in the NHS model was then assessed in the EIRA validation datasets.

Table 1.

Factors included in Primary model in NHS and Expanded models in NHS and EIRA

| Factors | Primary Model | Expanded NHS Model | Expanded EIRA Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiological and Environmental |

year of birth | year of birth | year of birth |

| smoking | smoking | smoking | |

| alcohol | alcohol | alcohol | |

| education | education | education | |

| parity (F1) | parity/breastfeeding(F1) | parity (F1) | |

| menses <12 yrs old(F1) | silica (M2) | ||

| menstrual | |||

| irregularity(F1) | mineral oil (M3) | ||

| menopause(F1) | solvents (M) | ||

| PMH use(F1) | |||

| region (US) (F1) | region (Sweden) | ||

| HLA-SE (0, 1, 2) | HLA-SE (0, 1, 2) (F1) | HLA-SE (0, 1, 2) | |

|

|

|||

| Genetic | GRS31 | GRS31 | GRS31 |

| GSTT1 | GSTT1 | ||

| HMOX1 | HMOX1 | ||

|

|

|||

| Gene-Environment Interactions |

HLA-SE*smoking | HLA-SE*smoking | HLA-SE*smoking |

| GSTT1*smoking | GSTT1*smoking | ||

| HMOX1*smoking | HMOX1*smoking | ||

| silica*smoking (M2) | |||

| mineral oil*smoking (M3) | |||

| solvent*smoking (M) | |||

F = in Females only, M = in Males only

Subjects with occupational exposure to rock drilling or stone crushing, or stone dust were classified as silica exposed

Subjects with occupational exposure to cutting oil, motor oil, form oil, hydraulic oil or asphalt were classified as exposed to mineral oil

As a secondary analysis, we studied expanded risk models that considered all variables including those available only in one cohort or discovered in either NHS or EIRA. For EIRA males, we excluded parity but added silica, mineral oil and solvents to the expanded models. These models were further categorized according to variable groups: epidemiological and environmental factors (E), genetic factors (G) and gene-environment interactions (GEI). In order to assess the benefit of adding G variables and GEI terms to risk models we compared models with just E variables, to those with E+G and finally models with E+G+GEI. These models were developed in a stepwise fashion in each dataset (NHS, EIRA women, EIRA men). The optimal combination of variables was chosen based on significant contribution to the model using the IDI explained below.

Model assessment and comparisons

Models were assessed on variance explained, goodness-of-fit and discrimination ability. The Nagelkerke R2 was used as a measure of variance explained by the model52. Goodness-of-fit was measured using the Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2, (χ2HL), where a non-significant χ2HL indicates a good model fit53. Finally, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) were used to assess how well each model discriminates between RA cases and controls. Confidence intervals (95%) were obtained via bootstrapping. The models were compared within each dataset using the Integrated Discrimination Improvement (IDI), both to decide on inclusion in the primary NHS model (then tested in EIRA) and also between models in the expanded analysis. Finally, the continuous Net Reclassification Improvement (cNRI) was used to compare the primary and validation models to the optimal model from the expanded analyses, within each dataset.

Developed by Pencina and D’Agostino54, 55, the IDI is a measure of overall improvement in sensitivity and specificity between 2 models (eg. E model compared with E+G model). It is calculated using the predicted probability of the outcome (seropositive RA or ACPA positive RA) in 2 models as follows:

One limitation is that IDI is calculated using predicted probabilities, which are biased in a case-control design since the probability of RA in the sample is not an estimate of probability of RA in the population. However, for our analyses we used the IDI to compare models within the same cohort, not to generalize across cohorts or to the general population.

To further address this issue, we also use the continuous Net Reclassification Improvement (cNRI) developed by Pencina and D’Agostino55. Whereas the original NRI required categories of risk and quantified the overall upward and downward movement between categories54, the new cNRI does not require categories. The cNRI55 quantifies any movement in predicated probability from the models. This can also be thought of as the amount of correct reclassification among event and non-events without respect to the magnitude of the change in predicted risk.

The cNRI is calculated as

Depending upon the future application of a prediction model, an improvement in reclassification of cases may be more important than that of controls, or vice versa. The cNRI can thus be interpreted for cases (cNRI(events)) and for controls (cNRI(non-events)) separately.

RESULTS

Primary models

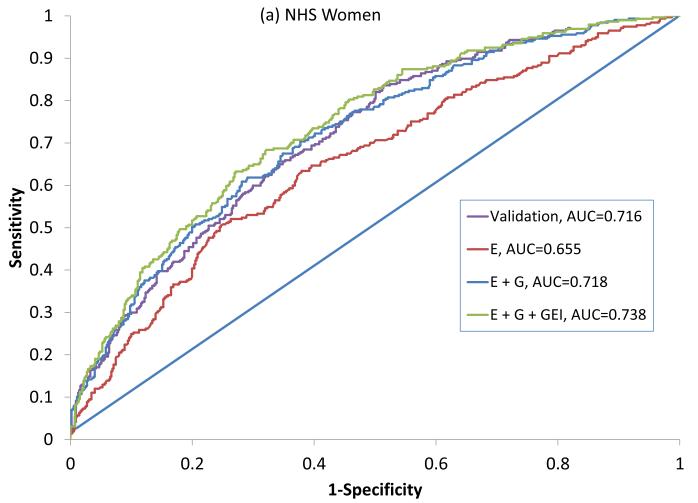

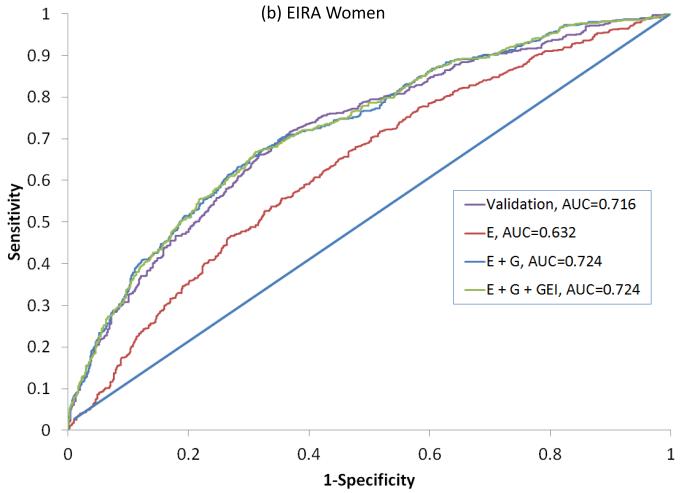

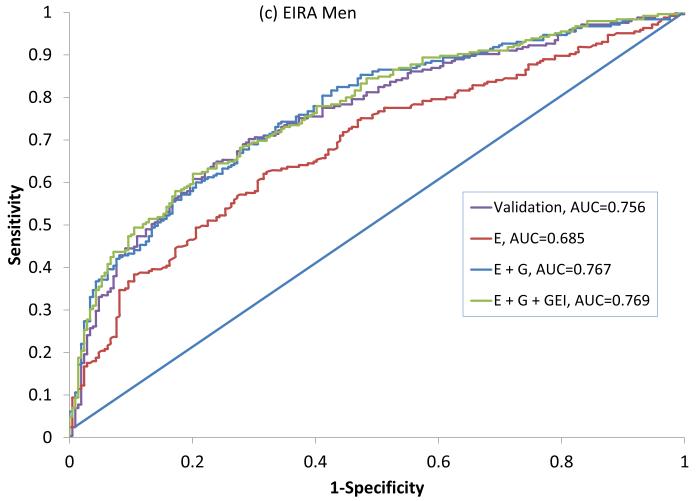

In NHS, 317 seropositive RA cases had a mean age at diagnosis of 56 (±10) years and 195 (63%) were current or former smokers (Table 2). In EIRA, 987 ACPA-positive RA cases had a mean age at diagnosis of 51 (±12), 644 (73%) were current or former smokers and 702 (71%) were female. All variables available were included in the final primary model since the addition of each variable improved the predicative ability of the model in NHS as measured by the IDI. This combination of variables showed an AUC of 0.716 (0.681-0.755) in NHS, 0.722 (0.692-0.746) in EIRA women and 0.756 (0.725 – 0.808) in EIRA men (Figure 1, Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants in the NHS and EIRA

| NHS | EIRA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seropositive RA cases (n=317) |

Controls (n=551) |

ACPA+ RA cases (n=987) |

Controls (n=958) |

|

| Age, mean (SD)1 | 55.1 (±8.1) | 55.5 (±7.9) | 51.2 (±12.0) | 52.5 (±11.7) |

| Female, n (%) | 317 (100%) | 551 (100%) | 702 (71%) | 715 (75%) |

| Current or past smoker, n (%) | 195 (63%) | 309 (56%) | 644 (73%) | 518 (59%) |

| Pack-years among smokers, mean (SD) | 25.0 (±18.0) | 22.7 (±20.9) | 19.2 (±14.8) | 16.5 (±14.6) |

| GRS39 (with HLA-SE), mean (SD) | 5.14 (±0.86) | 4.70 (±0.79) | 5.39 (±0.95) | 4.72 (±0.81) |

| GRS31 (without HLA-SE), mean (SD) | 4.27 (±0.60) | 4.10 (±0.86) | 4.51 (±0.59) | 4.26 (±0.58) |

| RA features | ||||

| Mean age at symptom onset, mean (SD) | 55.5 (±10.4) | - | 50.3 (±12.1) | |

| Mean age at diagnosis, mean (SD) | 56.1 (±9.8) | - | 51.1 (±12.1) | |

| RF positive, n (%) | 297 (94%) | - | 835 (88%) | |

| ACPA2-positive, n (%) | 112 (55%) | - | 987 (100%) | |

| Seropositive3, n (%) | 317 (100%) | - | 987 (100%) | |

Age at blood draw for blood samples (n=328 cases, n=334 controls)

Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) assayed in subset of NHS cases (n=202) with available blood samples collected at different points with respect to RA onset, up to 14 years prior to onset or up to 12 years after diagnosis

RF and/or ACPA

Figure 1.

ROC curves for predicting seropositive RA in NHS (a) and ACPA positive RA in EIRA women (b) and EIRA men (c). Variables included in the primary model (NHS) and Validation models (EIRA) are described in Table 1. ROC: Receiver Operating Characteristic, AUC: Area Under the Curve, NHS: Nurses’ Health Study, EIRA: Epidemiologic Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis, ACPA: anti-citrullinated antibody, E: Epidemiologic model, E + G: Epidemiologic + Genetic model, E + G + GEI: Epidemiologic + Genetic + Gene Environment Interaction model.

Table 3.

Results of primary model development in NHS and validation in EIRA females and EIRA males

| Statistical Parameters | Primary Dataset NHS Women |

Validation Dataset EIRA Women |

Validation Dataset EIRA Men |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.185 (0.129 – 0.246) | 0.185 (0.147 – 0.241) | 0.275 (0.189 – 0.360) |

| AUC | 0.716 (0.681-0.755) | 0.716 (0.693 – 0.749) | 0.756 (0.725 – 0.808) |

| χ 2 hl | 5.48 (0.71) | 8.71 (p=0.367) | 4.40 (p=0.810) |

Primary model includes year of birth, smoking (pkyrs), alcohol, education, parity (Females only), GRS31, HLA-DR and HLA*smoking

Secondary models

Secondary analyses were done specific to the expanded list of variables available in each dataset. All models that included G performed significantly better than the E models, based on the Nagelkerke R2, AUC, IDI and cNRI (Table 4). The expanded model in NHS women that included additional reproductive variables, and additional genetic and GEI terms produced the highest AUC (in NHS) of 0.738 (95%CI: 0.721 – 0.790) (Figure 1a). An optimal expanded model in EIRA women produced an AUC of 0.728 (95%CI: 0.705 – 0.758) and included the GRS and HLA-SE, but not GEI with smoking as these did not increase prediction (eg. addition of the HLA-SE*smoking interaction term did not show improvement with the IDI) (Figure 1b). The optimal expanded model in EIRA men that included occupational exposures produced the highest AUC of 0.769 (95%CI: 0.747 – 0.830), and included the GRS, HLA*smoking interaction, but not other GEI (Figure 1c).

Table 4.

Comparisons of the expanded models including epidemiologic and environmental factors (E), plus genetic factors (E+G), plus gene environment interaction terms (E+G+GEI) models for NHS and EIRA women, and EIRA men.

| NHS Expanded Models 1 | |||

| Statistical Parameters | E | E+G 2 | E+G+GEI3 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.094 (0.076 – 0.172) | 0.186 (0.162 – 0.279) | 0.209 (0.188 – 0.323) |

| AUC/c-statistic | 0.655 (0.635 – 0.709) | 0.718 (0.702 – 0.774) | 0.738 (0.723 – 0.795) |

| IDI (p-value) compared to | |||

| E model | ref | 0.069 (p=6.0 × 10−14) | 0.088 (p=7.4 × 10−17) |

| E+G model | −0.069 (p=6.0 × 10−14) | ref | 0.019 (p=0.0001) |

| E+G+GEI model | −0.088 (p=7.4 × 10−17) | −0.019 (p=0.0001) | ref |

| EIRA Women Expanded Models 1 | |||

| Statistical Parameters | E | E+G 2 | E+G+ GEI |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.069 (0.055 – 0.117) | 0.199 (0.169-0.265) | 0.200 (0.171 – 0.267) |

| AUC/c-statistic | 0.632 (0.614 – 0.671) | 0.724 (0.705 – 0.758) | 0.724 (0.706 – 0.762) |

| IDI (p-value) compared to | |||

| E model | ref | −0.101 (1.0 × 10−35) | 0.102 (8.4 × 10−36) |

| E+G model | −0.101 (1.0 × 10−35) | ref | 0.0002 (0.499) |

| E+G+GEI model | −0.102 (8.4 × 10−36) | --0.0002 (0.499) | ref |

| EIRA Men Expanded Models 1 | |||

| Statistical Parameters | E | E+G 2 | E+G+GEI 3 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.125 (0.098 – 0.237) | 0.273 (0.231 – 0.401) | 0.282 (0.240 – 0.414) |

| AUC/c-statistic | 0.685 (0.657 – 0.752) | 0.767 (0.744 – 0.828) | 0.769 (0.747 – 0.830) |

| IDI (p-value) compared to | |||

| E model | ref | 0.116 (p=1.1 × 10−14) | 0.123 (p=2.2 × 10−15) |

| E+G model | −0.116 (p=1.1 × 10−14) | ref | 0.006 (p=0.12) |

| E+G+GEI model | −0.123 (p=2.2 × 10−15) | −0.006 (p=0.12) | ref |

Expanded E model includes year of birth, smoking (pkyrs), alcohol, education, region of US (NHS) or Sweden (EIRA), parity (Females only), breastfeeding years (NHS only), age of menses (<12 vs ≥12, NHS only), menstual irregularity (NHS only), silica and mineral oil exposure (EIRA men only);

E+G includes E model + GRS31 and HLA-DR (0,1,2);

E+G+GEI includes E+G model + HLA-DR*smoking, [HMOX1, HMOX1*smoking, GSTT1, GSTT1*smoking (NHS Only)]

Model comparisons across groups of risk factors

In NHS, the primary model with age, smoking, alcohol, education, parity, GRS 31, HLA-SE and HLA*smoking explained 19% of the variance, whereas in the NHS expanded models the variance explained from just the epidemiologic factors (E model) was 9%. As expected, however, as more variables were added to the expanded model the variance explained increased, first to 19% with inclusion of genetic factors, and finally to 21% with the addition of GxE interaction (E+G+GEI mode). In EIRA women, the primary model explained 19% of the variance in women and 28% of the variance in men. In the expanded analysis among EIRA women, the variance explained from just the epidemiologic factors (E model) was 7%, and as more variables were added, the variance explained increased to 21% with inclusion of genetic factors and was 20% with inclusion of GEI factors. In EIRA men, the primary model explained 27.5% of the variance. In the expanded model for EIRA men, the variance explained by the epidemiologic factors (E model) was 12.5%, and as more variables were added, the variance explained increased to 27.3% with inclusion of genetic factors and to 28.2% with the inclusion of GEI variables.

In NHS expanded models, the addition of G, showed a significant improvement in prediction over the E model as measured with the IDIp=6×10−14); addition of GEI further improved the IDI and (p=0.0001), respectively. For EIRA women, addition of G in the expanded models showed significant improvement in prediction over the E model as measured by the IDI (p < 6.7 × 10−37), however, no improvement in IDI was seen with the addition of GEI terms (p>0.05). In EIRA men. expanded models, the addition of G and G+GEI each showed a significant improvement in prediction over the E model (p=1.1 × 10−14 and p=2.2 × 10−15, respectively). However, there was no significant improvement in IDI adding GEI to the E+G model.

The stratified cNRI results presented in Table 5 illustrate the change in sensitivity (reclassification of cases) and change in specificity (reclassification of controls) of the primary model compared to the expanded models. In NHS overall, the primary model performed more poorly than the E+G+GEI, with a total cNRI of −0.26 (p=0.0004), indicating lower specificity. However, from the stratified results we can see that the primary model performed similarly in reclassifying cases (same sensitivity), (cNRI = −0.03, p=0.64), but worse in reclassifying controls (lower specificity) (cNRI = −0.23, p=1.3 × 10−7). This is interpreted as an excess of 23% of controls reclassified with a higher predicted probability of RA in the primary model vs. the E+G+GEI model. In EIRA women, the primary model performed similarly to the E+G model (p=0.08). However, in the stratified analysis the primary model correctly reclassified controls with lower predicted probabilities (higher specificity) (cNRI = 0.33, p=5.9 × 10−18), and also reclassified cases with lower probabilities of developing RA (lower sensitivity) (cNRI = −0.42, p=5.0 × 10− 28). In EIRA men, the primary model performed worse than the E+G+GEI model according to the cNRI of −0.27 (p=0.004) (lower specificity). However, again in the stratified analysis, the primary model performed similarly to the E+G+GEI model in reclassifying controls (same specificity), (cNRI = 0.08, p=0.24), but did more poorly in reclassifying cases (lower sensitivity) (cNRI = −0.36, p=2.8 × 10−8).

Table 5.

Stratified analysis of reclassification of cases and controls comparing the primary or validation model to the optimal expanded model1

| Cohort | cNRI for Cases | cNRI for Controls | Total cNRI |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHS | −0.027 (p=0.64) | −0.233 (p=1.3 × 10−7) | −0.260 (p=0.0004) |

| EIRA (Women) | −0.424 (p<1.0 × 10−16) | 0.328 (p<1.0 × 10−16) | −0.096 (p=0.08) |

| EIRA (Men) | −0.355 (p=2.8 × 10−8) | 0.081 (p=0.24) | −0.274 (p=0.004) |

Expanded model for NHS is the E+G+GEI and for EIRA men and women are the E+G.

DISCUSSION

Leveraging an extensive body of epidemiologic and genetic research on the risk of developing RA among asymptomatic cohorts along with modern statistical techniques, we developed and validated comprehensive risk models for RA. We demonstrate that inclusion of information on genetic variants and gene environment interactions models, significantly improves the predictive power of epidemiologic models. Using the AUC to assess discriminative ability, the optimal primary model among a US female cohort included gene-environment interaction terms for HLA-DRB1, the strongest genetic risk factor for RA and smoking, the strongest environment risk factor for RA, with an AUC of 0.716. The optimal primary model among a Swedish cohort was seen for women with an AUC of 0.716 and for men with an AUC of 0.756. Expanded models demonstrated improved AUCs to 0.738 among US women, 0.724 among Swedish women and 0.769 among Swedish men. The variance explained by the expanded epidemiologic, genetic, and gene-environment interaction models ranged from 21% for women to 28% for men suggested that there are more risk factors yet to be discovered.

We demonstrate that optimal models for prediction of RA should include epidemiologic, genetic and, in some cases, their interaction terms. In other diseases and complex traits, for example type II diabetes56-61 and cardiovascular disease62, 63 variants have at most provided at only a modest increase in predictive ability of clinical models. Willems and colleagues reviewed 20 studies assessing risk prediction for type II diabetes and found that adding genetic factors (up to 40 polymorphisms) did not add significantly to the discriminative ability of any of the clinical models64. They showed that where the epidemiologic models are strong (AUCs ranging from 0.68 – 0.92), adding genetic variants with weak effects (even as a cumulative genetic risk score) does not add much to prediction. In a simulation study to explore the potential improvement in discrimination with models that include G−G and G−E interactions, Aschard, et. al demonstrated that inclusion of interaction effects in models for three diseases (breast cancer, type 2 diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis) was unlikely to dramatically improve the discrimination ability of these models65. This study of RA risk is one of the few examples where the inclusion of G and GEI factors in a model resulted in a significant increase in discrimination and reclassification.

Using a primary model consisting of 5 clinical variables that could be collected at a routine clinic visit could be advantageous when screening large numbers of individuals for RA risk. These results are timely as selection of high risk individuals in enrollment in primary prevention trials is an exciting in RA research 66, 67. Thus, we strived to construct a model that performed well statistically, but also included clinical variables that could be collected on a larger scale. The variables for our model were chosen such that all the epidemiological factors could be easily attained by survey (eg. year of birth, smoking, alcohol, education and parity). We studied whether the predictive ability of the model improved with an expanded set of predictors that could be assessed with longer surveys along with genetic risk alleles. We showed that although there were slightly lower AUC statistics in the primary models, the predictive accuracies were significantly lower than the expanded models, as demonstrated by the cNRI results stratified into case and control subgroups. This demonstrates the importance of considering statistical evaluation beyond analysis of AUC statistics 54, 55, 68-70.

If these results were applied to selecting high risk individuals for a prevention trial, the expanded set of variables should be collected by survey, and genetic risk factors should be assessed. Alternatively family history may be a good proxy for genetic risk alleles (although family history information on all subjects was not available in our study). Among men in EIRA, the primary model classified cases as having a lower predicted probability than the expanded model, or lower sensitivity, but had similar specificity to the full model. Among EIRA women, the primary model resulted in a significant decrease in sensitivity, with 42% of cases being classified with lower predicted probabilities; however, there was also an increase in specificity, with 33% of controls being classified with lower predicted probabilities. This would result in fewer potential cases qualifying to be randomized in a trial among men and women, but also reduced false positive fraction (FPF) among women, lowering the chance of unnecessary treatment. However, the performance of the primary model compared to the expanded model in the NHS dataset suggests lower specificity, with 22% of the controls being incorrectly reclassified with a higher predicted probability and no change in sensitivity. This would lead in an increase in FPF, which would result in more women being enrolled and treated unnecessarily. When considering a prognostic model for enrollment in a prevention trial targeted to high-risk groups, maintaining high specificity (and thus low false positive rate) has a higher priority than increasing sensitivity in the setting of treatment with a potentially toxic medication.

One limitation of this study is that models were developed in primarily Caucasian populations. There may be epidemiologic, genetic, or gene-environment interaction factors that might lead to differences in risk models in non-Caucasian populations. Hence, the predictive models developed in this dataset need to be validated in other populations. Another limitation of this study is some factors in the models were originally discovered in NHS or EIRA. These include region of residence and GSTT1 by smoking interaction (NHS), and HLA by smoking, silica and solvents (EIRA)10, 14, 15, 42, 71. Thus, the results of the expanded models could be inflated due to over-fitting. We also recognize that assessing the models on the dataset in which they were developed leads to optimistic measures of variance explained and discrimination. The primary limitation of the study design is that in a matched case control study, we cannot estimate weights for each factor that could be used in other studies, or used in clinical prediction. However, the wealth of data allowed us to gain insights into the optimal collection of variables that should be included in prospective studies for development of prediction rules. Further, although the NHS cohorts involved > 230,000 women, blood was collected on < 25% of women, thus limiting the sample size for analyses that include genetic factors. Finally, blood samples were collected after RA diagnosis in most subjects in NHS and all subjects in EIRA, thus we do not have biomarker data among pre-clinical RA collected prior to the onset of RA symptoms, such as such as autoantibodies or cytokines that have been shown to be strongly associated with risk of development of RA 48, 72-76.

The strength of this study is the use of statistical metrics to parse the effect of the addition of each factor to a model. Over the last decade, limitations of using change in AUC as a primary outcome when comparing both diagnostic and prognostic models has been widely discussed54, 55, 69, 77. Cook 77 and Pepe, et al 69 separately showed that any new factor would require an exceptionally large OR to show an impact on the AUC. Both Pencina54, 55 and Cook77 pointed out that for assessing the utility of a prognostic model we are interested in reclassification to a more appropriate risk category (higher for cases and lower for controls), rather than discrimination. By using the IDI, which measures reclassification, we can perform model comparison because the same scale is used in all situations. Even with our relatively modest sample size in NHS, we had >90% power to find an IDI as small as 0.02 and >80% to find a cNRI as small as 0.15. We were able to show the benefit of adding G and GEI terms to an E model in the expanded models.

These results illustrate the challenges of creating a simple risk prediction model for primary prevention trials of RA. Thus, further work on development of highly specific prediction models using prospective cohorts to assess weights is still needed for primary prevention trials. Our data suggests that addition of cumulative RA genetic variants as a genetic risk score and, in some cases, gene-environment interactions to an RA prediction model with epidemiologic factors significantly improves the predictive ability of the model for this complex human autoimmune disease. However, the inclusion of highly specific biomarkers such as ACPA in risk models is likely to improve risk stratification of asymptomatic individuals. Further, we show that identifying risk factors separately in men and women is important, particularly if occupational exposures differ. Ultimately, this collection of variables should be used to estimate weights in other cohorts, then the models validated and their performance assessed before using them for risk stratification.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1. Loci, risk alleles, weights, genotype frequencies and associations with seropositive RA in NHS and ACPA+ RA EIRA for 39 alleles, 8 alleles in HLA-SE and 31 alleles in GRS31

Significant findings.

Environmental factors, genetic factors and gene-environmental interactions are associated with the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis in asymptomatic populations.

RA risk models that include genetic factors and gene-environmental interaction terms are more accurate in modeling risk than those with environmental factors alone.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Studies in the USA and the Epidemiologic Investigation of RA in Sweden for their contributions.

Financial disclosures: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants CA87969, CA49449, CA50385, CA67262, AR049880, AR052403, AR047782). The EIRA study was supported by grants from the Swedish Medical Research Council, from the Swedish Council for Working life and Social Research, from King Gustaf V’s 80-year foundation, from the Swedish Rheumatism Foundation, from Stockholm County Council, from the insurance company AFA, the European Union supported AutoCure project, FAMRI (Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute, and from the COMBINE (Controlling chronic inflammatory diseases with combined efforts) project. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lahiri M, Morgan C, Symmons DP, Bruce IN. Modifiable risk factors for RA: prevention, better than cure? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51(3):499–512. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karlson EW, Chang SC, Cui J, et al. Gene-environment interaction between HLA-DRB1 shared epitope and heavy cigarette smoking in predicting incident rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):54–60. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.102962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugiyama D, Nishimura K, Tamaki K, et al. Impact of smoking as a risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):70–81. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.096487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voigt LF, Koepsell TD, Nelson JL, Dugowson CE, Daling JR. Smoking, obesity, alcohol consumption, and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Epidemiology. 1994;5(5):525–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Symmons DP, Bankhead CR, Harrison BJ, et al. Blood transfusion, smoking, and obesity as risk factors for the development of rheumatoid arthritis: Results from a primary care-based incident case-control study in Norfolk, England. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1955–61. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Criswell LA, Merlino LA, Cerhan JR, et al. Cigarette smoking and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis among postmenopausal women: results from the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Am J Med. 2002;112(6):465–71. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stolt P, Bengtsson C, Nordmark B, et al. Quantification of the influence of cigarette smoking on rheumatoid arthritis: results from a population based case-control study, using incident cases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(9):835–41. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.9.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen M, Jacobsen S, Klarlund M, et al. Environmental risk factors differ between rheumatoid arthritis with and without auto-antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptides. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(4):R133. doi: 10.1186/ar2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costenbader KH, Feskanich D, Mandl LA, Karlson EW. Smoking intensity, duration, and cessation, and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis in women. Am J Med. 2006;119(6):503–11. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costenbader KH, Chang SC, Laden F, Puett R, Karlson EW. Geographic variation in rheumatoid arthritis incidence among women in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(15):1664–70. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vieira VM, Hart JE, Webster TF, et al. Association between residences in U.S. northern latitudes and rheumatoid arthritis: A spatial analysis of the Nurses’ Health Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(7):957–61. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hart JE, Laden F, Puett RC, Costenbader KH, Karlson EW. Exposure to traffic pollution and increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(7):1065–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sluis-Cremer GK, Hessel PA, Hnizdo E, Churchill AR. Relationship between silicosis and rheumatoid arthritis. Thorax. 1986;41(8):596–601. doi: 10.1136/thx.41.8.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stolt P, Kallberg H, Lundberg I, Sjogren B, Klareskog L, Alfredsson L. Silica exposure is associated with increased risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Swedish EIRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(4):582–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.022053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sverdrup B, Kallberg H, Bengtsson C, et al. Association between occupational exposure to mineral oil and rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Swedish EIRA case-control study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(6):R1296–303. doi: 10.1186/ar1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hazes JM, Dijkmans BA, Vandenbroucke JP, de Vries RR, Cats A. Lifestyle and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption. AnnRheumDis. 1990;49(12):980–2. doi: 10.1136/ard.49.12.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerhan JR, Saag KG, Criswell LA, Merlino LA, Mikuls TR. Blood transfusion, alcohol use, and anthropometric risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis in older women. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(2):246–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kallberg H, Jacobsen S, Bengtsson C, et al. Alcohol consumption is associated with decreased risk of rheumatoid arthritis: results from two Scandinavian case-control studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(2):222–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.086314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spector TD, Roman E, Silman AJ. The pill, parity, and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(6):782–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romieu I, Hernandez-Avila M, Liang MH. Oral contraceptives and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of a conflicting literature. Br J Rheumatol. 1989;28(Suppl 1):13–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/xxviii.suppl_1.13. discussion 8-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spector TD, Hochberg MC. The protective effect of the oral contraceptive pill on rheumatoid arthritis: an overview of the analytic epidemiological studies using meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(11):1221–30. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90023-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pladevall-Vila M, Delclos GL, Varas C, Guyer H, Brugues-Tarradellas J, Anglada-Arisa A. Controversy of oral contraceptives and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: meta-analysis of conflicting studies and review of conflicting meta-analyses with special emphasis on analysis of heterogeneity. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144(1):1–14. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jorgensen C, Picot MC, Bologna C, Sany J. Oral contraception, parity, breast feeding, and severity of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(2):94–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.2.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karlson EW, Mandl LA, Hankinson SE, Grodstein F. Do breast-feeding and other reproductive factors influence future risk of rheumatoid arthritis? Results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(11):3458–67. doi: 10.1002/art.20621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doran MF, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. The effect of oral contraceptives and estrogen replacement therapy on the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a population based study. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):207–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walitt B, Pettinger M, Weinstein A, et al. Effects of postmenopausal hormone therapy on rheumatoid arthritis: the women’s health initiative randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(3):302–10. doi: 10.1002/art.23325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pikwer M, Bergstrom U, Nilsson JA, Jacobsson L, Berglund G, Turesson C. Breast feeding, but not use of oral contraceptives, is associated with a reduced risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(4):526–30. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.084707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pikwer M, Bergstrom U, Nilsson JA, Jacobsson L, Turesson C. Early menopause is an independent predictor of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(3):378–81. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.200059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olsson AR, Skogh T, Wingren G. Aetiological factors of importance for the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33(5):300–6. doi: 10.1080/03009740310004748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bengtsson C, Nordmark B, Klareskog L, Lundberg I, Alfredsson L. Socioeconomic status and the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Swedish EIRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(11):1588–94. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.031666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedersen M, Jacobsen S, Klarlund M, Frisch M. Socioeconomic status and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a Danish case-control study. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(6):1069–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernando MM, Stevens CR, Walsh EC, et al. Defining the role of the MHC in autoimmunity: a review and pooled analysis. PLoS genetics. 2008;4(4):e1000024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Begovich AB, Carlton VE, Honigberg LA, et al. A missense single-nucleotide polymorphism in a gene encoding a protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPN22) is associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(2):330–7. doi: 10.1086/422827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plenge RM, Cotsapas C, Davies L, et al. Two independent alleles at 6q23 associated with risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2007;39(12):1477–82. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Remmers EF, Plenge RM, Lee AT, et al. STAT4 and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(10):977–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plenge RM, Seielstad M, Padyukov L, et al. TRAF1-C5 as a risk locus for rheumatoid arthritis--a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(12):1199–209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raychaudhuri S, Remmers EF, Lee AT, et al. Common variants at CD40 and other loci confer risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2008;40(10):1216–23. doi: 10.1038/ng.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raychaudhuri S, Thomson BP, Remmers EF, et al. Genetic variants at CD28, PRDM1 and CD2/CD58 are associated with rheumatoid arthritis risk. Nat Genet. 2009;41(12):1313–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stahl EA, Raychaudhuri S, Remmers EF, et al. Genome-wide association study meta-analysis identifies seven new rheumatoid arthritis risk loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42(6):508–14. doi: 10.1038/ng.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Padyukov L, Silva C, Stolt P, Alfredsson L, Klareskog L. A gene-environment interaction between smoking and shared epitope genes in HLA-DR provides a high risk of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(10):3085–92. doi: 10.1002/art.20553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klareskog L, Stolt P, Lundberg K, et al. A new model for an etiology of rheumatoid arthritis: Smoking may trigger HLA-DR (shared epitope)-restricted immune reactions to autoantigens modified by citrullination. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):38–46. doi: 10.1002/art.21575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keenan BT, Chibnik LB, Cui J, et al. Effect of interactions of glutathione S-transferase T1, M1, and P1 and HMOX1 gene promoter polymorphisms with heavy smoking on the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(11):3196–210. doi: 10.1002/art.27639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kannel WB. The Framingham Study: historical insight on the impact of cardiovascular risk factors in men versus women. J Gend Specif Med. 2002;5(2):27–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Avins AL, Browner WS. Improving the prediction of coronary heart disease to aid in the management of high cholesterol levels: what a difference a decade makes. Jama. 1998;279(6):445–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.6.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sytkowski PA, Kannel WB, D’Agostino RB. Changes in risk factors and the decline in mortality from cardiovascular disease. The Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(23):1635–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006073222304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deane KD, Norris JM, Holers VM. Preclinical rheumatoid arthritis: identification, evaluation, and future directions for investigation. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2010;36(2):213–41. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karlson EW, Sanchez-Guerrero J, Wright EA, et al. A connective tissue disease screening questionnaire for population studies. AnnEpidemiol. 1995;5(4):297–302. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00096-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karlson EW, Chibnik LB, Tworoger SS, et al. Biomarkers of inflammation and development of rheumatoid arthritis in women from two prospective cohort studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(3):641–52. doi: 10.1002/art.24350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM. The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota, 1955-1985. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(3):415–20. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:3<415::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karlson EW, Chibnik LB, Kraft P, et al. Cumulative association of 22 genetic variants with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis risk. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):1077–85. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.120170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Janssens AC, Ioannidis JP, van Duijn CM, Little J, Khoury MJ, Group G. Strengthening the reporting of Genetic Risk Prediction Studies: the GRIPS statement. Genet Med. 2011;13(5):453–6. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318212fa82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nagelkerke N. A note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biometrika. 1991;78(3):691–2. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW., Jr. A review of goodness of fit statistics for use in the development of logistic regression models. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115(1):92–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr., D’Agostino RB, Jr., Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27(2):157–72. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. discussion 207-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr., Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med. 2011;30(1):11–21. doi: 10.1002/sim.4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Balkau B, Lange C, Fezeu L, et al. Predicting diabetes: clinical, biological, and genetic approaches: data from the Epidemiological Study on the Insulin Resistance Syndrome (DESIR) Diabetes Care. 2008;31(10):2056–61. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Miguel-Yanes JM, Shrader P, Pencina MJ, et al. Genetic risk reclassification for type 2 diabetes by age below or above 50 years using 40 type 2 diabetes risk single nucleotide polymorphisms. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):121–5. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Janssens AC, Gwinn M, Khoury MJ, Subramonia-Iyer S. Does genetic testing really improve the prediction of future type 2 diabetes? PLoS medicine. 2006;3(2):e114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030114. author reply e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lyssenko V, Jonsson A, Almgren P, et al. Clinical risk factors, DNA variants, and the development of type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2220–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meigs JB, Shrader P, Sullivan LM, et al. Genotype score in addition to common risk factors for prediction of type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2208–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Talmud PJ, Hingorani AD, Cooper JA, et al. Utility of genetic and non-genetic risk factors in prediction of type 2 diabetes: Whitehall II prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2010;340:b4838. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4838. (Clinical research ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aulchenko YS, Ripatti S, Lindqvist I, et al. Loci influencing lipid levels and coronary heart disease risk in 16 European population cohorts. Nat Genet. 2009;41(1):47–55. doi: 10.1038/ng.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paynter NP, Chasman DI, Buring JE, Shiffman D, Cook NR, Ridker PM. Cardiovascular disease risk prediction with and without knowledge of genetic variation at chromosome 9p21. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;150(2):65–72. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-2-200901200-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Willems SM, Mihaescu R, Sijbrands EJ, van Duijn CM, Janssens AC. A methodological perspective on genetic risk prediction studies in type 2 diabetes: recommendations for future research. Current diabetes reports. 2011;11(6):511–8. doi: 10.1007/s11892-011-0235-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aschard H, Chen J, Cornelis MC, Chibnik LB, Karlson EW, Kraft P. Inclusion of gene-gene and gene-environment interactions unlikely to dramatically improve risk prediction for complex diseases. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(6):962–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Dongen H, van Aken J, Lard LR, et al. Efficacy of methotrexate treatment in patients with probable rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1424–32. doi: 10.1002/art.22525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verstappen SM, McCoy MJ, Roberts C, Dale NE, Hassell AB, Symmons DP. Beneficial effects of a 3-week course of intramuscular glucocorticoid injections in patients with very early inflammatory polyarthritis: results of the STIVEA trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(3):503–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.119149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cook NR. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation. 2007;115(7):928–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.672402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pepe MS, Janes H, Longton G, Leisenring W, Newcomb P. Limitations of the odds ratio in gauging the performance of a diagnostic, prognostic, or screening marker. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(9):882–90. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ridker PM, Buring JE, Rifai N, Cook NR. Development and validation of improved algorithms for the assessment of global cardiovascular risk in women: the Reynolds Risk Score. JAMA. 2007;297(6):611–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.6.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Klareskog L, Padyukov L, Alfredsson L. Smoking as a trigger for inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19(1):49–54. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32801127c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, de Jong BA, Berglin E, et al. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(10):2741–9. doi: 10.1002/art.11223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nielen MM, van Schaardenburg D, Reesink HW, et al. Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(2):380–6. doi: 10.1002/art.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chibnik LB, Mandl LA, Costenbader KH, Schur PH, Karlson EW. Comparison of threshold cutpoints and continuous measures of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies in predicting future rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(4):706–11. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kokkonen H, Soderstrom I, Rocklov J, Hallmans G, Lejon K, Rantapaa Dahlqvist S. Up-regulation of cytokines and chemokines predates the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(2):383–91. doi: 10.1002/art.27186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sokolove J, Bromberg R, Deane KD, et al. Autoantibody epitope spreading in the pre-clinical phase predicts progression to rheumatoid arthritis. PloS one. 7(5):e35296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cook NR. Statistical evaluation of prognostic versus diagnostic models: beyond the ROC curve. Clin Chem. 2008;54(1):17–23. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.096529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1. Loci, risk alleles, weights, genotype frequencies and associations with seropositive RA in NHS and ACPA+ RA EIRA for 39 alleles, 8 alleles in HLA-SE and 31 alleles in GRS31