Abstract

Mitochondrial dysfunction represents a critical event during the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease (PD) and expanding evidences demonstrate that an altered balance in mitochondrial fission/fusion is likely an important mechanism leading to mitochondrial and neuronal dysfunction/degeneration. In this study, we investigated whether DJ-1 is involved in the regulation of mitochondrial dynamics and function in neuronal cells. Confocal and electron microscopic analysis demonstrated that M17 human neuroblastoma cells over-expressing wild-type DJ-1 (WT DJ-1 cells) displayed elongated mitochondria while M17 cells over-expressing PD-associated DJ-1 mutants (R98Q, D149A and L166P) (mutant DJ-1 cells) showed significant increase of fragmented mitochondria. Similar mitochondrial fragmentation was also noted in primary hippocampal neurons overexpressing PD-associated mutant forms of DJ-1. Functional analysis revealed that over-expression of PD-associated DJ- 1 mutants resulted in mitochondria dysfunction and increased neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress (H2O2) or neurotoxin. Further immunoblot studies demonstrated that levels of dynamin-like protein (DLP1), also known as Drp1, a regulator of mitochondrial fission, was significantly decreased in WT DJ-1 cells but increased in mutant DJ-1 cells. Importantly, DLP1 knockdown in these mutant DJ-1 cells rescued the abnormal mitochondria morphology and all associated mitochondria/neuronal dysfunction. Taken together, these studies suggest that DJ-1 is involved in the regulation of mitochondrial dynamics through modulation of DLP1 expression and PD-associated DJ-1 mutations may cause PD by impairing mitochondrial dynamics and function.

Keywords: DJ-1, Drp1, mitochondrial elongation, mitochondrial fragmentation, mitochondrial fusion, Parkinson disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s disease, characterized by the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons within the substantia nigra pars compacta (Mounsey and Teismann 2010). Pathogenic mutations in DJ-1 lead to autosomal recessive early-onset Parkinsonism but the underlying mechanisms remain elusive (Bonifati et al. 2003). DJ-1 is a small 20-kDa protein that is highly conserved across diverse species (Bandyopadhyay and Cookson 2004; Lucas and Marin 2007). Despite its multifunctional features, the most striking and consistent findings about DJ-1 is its involvement in the response to oxidative stress (Cookson 2010). Wild-type DJ-1 but not DJ-1 mutant protects cells from cytotoxicity caused by oxidative stress, and DJ-1 deficiency causes increased cellular vulnerability to oxidative insults: mice lacking DJ-1 show nigrostriatal dopaminergic deficits and hypokinesia (Goldberg et al. 2005), and are more sensitive to MPTP toxicity and oxidative stress (Kim et al. 2005), while mice over-expressing DJ-1 are resistant to MPTP toxicity (Paterna et al. 2007). Interestingly, oxidative stress was found to induce rapid re-localization of DJ-1 to mitochondria (Canet-Aviles et al. 2004; Junn et al. 2009), suggesting that mitochondria could be a site of neuroprotective action for DJ-1.

Compelling evidence suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of PD (Zhu and Chu 2010). In idiopathic PD, there are consistent and significant deficits in subunits and activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I (Bindoff et al. 1991; Mann et al. 1992). Complex I inhibitors such as 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) and rotenone induce a Parkinson-like clinical syndrome in human (Langston et al. 1983; Buckman et al. 1988; Schober 2004). More interestingly, several recently identified familial PD genes including PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1) and Parkin were involved in the function of mitochondria. Mitochondria are dynamic organelles that undergo continual fission/fusion events which not only regulate the morphology and distribution of mitochondria, but also serve crucial physiological function (Detmer and Chan 2007). Recent studies on PINK1 and Parkin suggest that dysregulation in mitochondrial dynamics and quality control could contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction during the pathogenesis of PD (Clark et al. 2006; Deng et al. 2008; Poole et al. 2008). Along this line, three most recent studies demonstrated that DJ-1 deficiency caused severe mitochondria fragmentation (Irrcher et al. 2010; Krebiehl et al. 2010; Thomas et al. 2011). However, the effect of PD-associated DJ-1 mutations on mitochondrial dynamics was not determined and how DJ-1 may modulate mitochondrial dynamics was not clear. Therefore, in this study, we examined the effects of over-expression of DJ-1 and PD-associated DJ-1 mutants on mitochondria dynamics and investigated the contribution of mitochondria dynamic abnormalities to DJ-1-induced mitochondria dysfunction and neuronal dysfunction.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection

The human dopaminergic neuroblastoma M17 cells were grown in Opti-MEM I medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), supplemented with 5% or 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin– streptomycin. Cells were transfected using Attractene (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Opti-MEM I culture medium containing 50 lg/mL zeocin (Invitrogen) and/or 20 lg/mL blasticidin was used for stable cell line selection. The selective medium was replaced every 3 or 4 days until the appearance of foci, each apparently derive from a single stably transfected cell. Stable cell lines were picked and maintained with 30 zeocin lg/mL and/or 5 lg/mL blasticidin. The successful over-expression of DJ-1 was verified by immunoblot and three independent clonal lines of each DJ-1 mutant with equal transgene expression were selected. All three clonal lines for each transgene were evaluated for each experimental method except for EM analysis. Primary neurons from E18 rat cortex (BrainBits) were seeded at 40 000–50 000 cells per well on 8-well chamber slides coated with poly-D-lysine/laminin (BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY, USA) in neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2% B27 (Invitrogen)/1 × GlutaMAX (Invitrogen) and maintained as we described (Wang et al. 2011b). At DIV 7, neurons were transfected using Neurofect (Genlantis, San Diego, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. For co-transfection, a 3 : 1 : 1 ratio (DJ-1 : GFP : mito-DsRed2) was applied. All cultures were kept at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 containing atmosphere.

Expression vectors, antibodies, chemicals and measurements

Mito-DsRed2 construct (Clontech) and V5-tagged wild-type DJ-1 or PD-associated DJ-1 R98Q, D149A and L166P mutants (gifts from Dr Mark Cookson, National Institutes of Health) were used. The miR RNAi sequence targeting the open reading frame region of human dynamin-like protein (DLP1) was described as previously (Wang et al. 2008a). Primary antibodies used included rabbit anti-DJ-1, rabbit anti-α -tubulin (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA, USA), mouse anti-DLP1, mouse anti-optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) (BD), mouse anti-mitofusin 1 (mfn1) and mitofusin 2 (mfn2) (Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-Fis1 (Imgenex, San Diego, CA, USA) and rabbit COX IV (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA). 1-Methyl-4-phenylpyridinium/ N-acetyl-L-cysteine (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and H2O2 (Sigma) were also obtained. Cell death and viability was measured by Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (LDH; Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN, USA). ATP levels were measured by the ATP Colorimetric/Fluorometric Assay Kit (Biovision, Milpitas, CA, USA). The reactive oxygen species (ROS) level (by H2DCFDA from Invitrogen) and mitochondrial membrane potential (by Rhodamine 123 (Rh123) from Invitrogen) was measured as described before (Wang et al. 2008b).

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed with 1 × cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling) plus 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma) and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma). Equal amounts of total protein extract (5 µg–10 µg) were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to Immobilon-P (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA, USA). Following blocking with 10% non-fat dry milk, primary and secondary antibodies were applied as previously described (Wang et al. 2008a) and the blots developed with Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore).

Immunofluorescence, electron microscopy and image analysis

For immunofluorescence, cells cultured on 4- or 8-well chamber slides were fixed and stained as described previously (Wang et al. 2008a). All fluorescence images were captured with a Zeiss LSM 510 inverted fluorescence microscope or a Zeiss LSM 510 inverted laser-scanning confocal fluorescence microscope as described before (Wang et al. 2009). For electron microscopic analysis, cells cultured on the Aclar embedding film (2 mm thickness; Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 4% sucrose in a 0.05 mol/L phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 and examined with a JEOL 1200EX electron microscope (Tokyo, Japan) as described before (Wang et al. 2008a). Image analysis was performed with WCIF ImageJ (developed by W. Rasband). Quantification of mitochondria morphology were performed as described before (Koopman et al. 2008). Briefly, raw images were background corrected, linearly contrast optimized, applied with a 7 × 7 ‘top hat’ filter, subjected to a 3 × 3 median filter and then thresholded to generate binary images. Most mitochondria were well separated in the resultant binary images and only large clusters of mitochondria were excluded automatically. These clusters were apparent only in the perinuclear region and occurred with similar frequency in all cell lines. After binary images were created, the whole cell was selected as region as interest, all mitochondria in the cell were then analyzed and, finally a mean value of aspect ratio was generated. The final quantification was from all cells we imaged in all three independent experiments. All binary images were analyzed by WCIF Image J.

Statistical analysis

Multi-group comparison was performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests using GraphPad Prism 5. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effect of PD-associated DJ-1 mutant on mitochondrial morphology

We first investigated the effect of DJ-1 on mitochondria dynamics in a panel of M17 human neuroblastoma clonal cell lines stably over-expressing of V5-tagged wild-type DJ- 1 (WT cells) or PD-associated DJ-1 R98Q, D149A and L166P mutants (R98Q, D149A and L166P cells). Three independent clonal lines of these DJ-1 variants with equal transgene expression were selected for the confocal microscopic analysis for mitochondria morphology. The successful over-expression of DJ-1 was verified by western blot (Fig. 1a). No significant changes in basal level cell death were noted in any of these cell lines compared with non-transfected control cells (control cells) or empty vector-transfected cells (vector cells) (not shown). To visualize mitochondria, these cells were transiently transfected with mito-DsRed2. Two days after transfection, cells were fixed, stained and imaged by laser confocal microscope. As reported previously, in most (> 95%) control and vector cells, mitochondria showed tubular form with a mean aspect ratio (a ratio between the major and the minor axes of the ellipse equivalent to the mitochondria as an index for mitochondrial morphology) of 2.5 ± 0.16 and 2.4 ± 0.12 respectively (Fig. 1a–d). Over-expression of WT DJ-1 resulted in the appearance of much longer mitochondrial tubules with a significantly increased mitochondrial aspect ratio (3.3 ± 0.18), suggestive of mitochondria elongation. In marked contrast, over-expression of pathogenic DJ-1 mutations significantly increased the percentage of cells with fragmented mitochondria as evidenced by the appearance of small round structures from 6.6 ± 1.35% in control cells to 33.2 ± 6.23% (R98Q cells), 29.3 ± 3.10% (D149A cells) and 36.6 ± 4.11% (L166P cells) respectively, and significantly decreased mitochondrial aspect ratio to 1.9 ± 0.12 (R98Q cells), 1.9 ± 0.08 (D149A cells) and 1.7 ± 0.14 (L166P cells) respectively (Fig. 1b–d), suggesting mitochondrial fragmentation.

Fig 1.

Effect of PD-associated DJ-1 mutant on mitochondrial morphology. (a) Representative blot shows the level of DJ-1 in human dopaminergic neuroblastoma M17 clonal lines that stably over-express V5-tagged wild-type DJ-1 (WT cells) or PD-associated mutant DJ-1 R98Q, D149A and L166P (R98Q, D149A and L166P cells). Upper DJ-1 band: exogenous V5 tagged DJ-1; Lower DJ-1 band: endogenous DJ-1. Equal protein amounts (10 µg) were loaded and tubulin was used as an internal loading control. (b) M17 cells were transfected with mito-DsRed2 to label mitochondria, fixed 2 days after transfection, immunostained with tubulin. Representative pictures of positively transfected cells are shown. Green: tubulin; red: mito- DsRed2; blue: DAPi. (c, d) Quantification of mitochondria morphology revealed significant decrease of mitochondria length (the aspect ratio of a mitochondrion is a ratio between the major and the minor axes of the ellipse equivalent to the mitochondria), and increase of cells displaying fragmented mitochondria compared with controls. For each cell line, at least 300 cells were measured in each experiment and experiments were repeated three times (*p < 0.05, when compared with the control cells; one-way anova followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

As there was no significant difference of cellular morphology, growth rate and mitochondrial morphology among the three independent clonal lines of each DJ-1 variant, we further confirmed our observations in ultrastructural studies on mitochondria in only one clonal line of each DJ-1 variant. Electron micrographs revealed long and thin mitochondrial tubules with intact cristae in the control cells and WT DJ-1 cells but round and significantly shorter mitochondria in R98Q, D149A and L166P cells (Fig. 2a–c). Detailed quantification analysis confirmed significant increased mitochondrial length in WT DJ-1 cells and decreased mitochondrial length in R98Q, D149A and L166P cells. Interestingly, there was slight but significant increase of mitochondria width in WT and mutant DJ-1 cells. The mitochondria size was increased significantly in WT, D149A and L166P cells. Importantly, damaged mitochondria as reflected by broken cristae structure was occasionally noticed in R98Q and D149A cells and became abundant in L166P cells but never identified in control cells or WT DJ-1 cells (Fig. 2a).

Fig 2.

EM analysis of mitochondrial morphology. (a) Representative micrographs of control, WT, R98Q, D149A and L166P cells M17 cells were shown (scale bars = 1 µm). (b, c) 3D scatter plot (b) and quantification (c) of mitochondrial width, length and size in control, WT, R98Q, D149A and L166P M17 cells.. For each cell line, at least 500 mitochondria were measured (*p < 0.05, when compared with the control cells; one-way anova followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

Effects of PD-associated DJ-1 mutant on mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins

As mitochondria morphology is regulated by mitochondrial fission (i.e. DLP1 and Fis1) and fusion proteins (i.e. OPA1, Mfn1 and Mfn2), we next investigated effect of DJ-1 over-expression on these proteins in all three independent clonal lines of DJ-1 variants (Fig. 3a and b). Immunoblot analysis revealed that, compared with control cells, both fission proteins, DLP1 and Fis1, were significantly reduced but no changes were found in fusion proteins in WT DJ-1 cells. In contrast, DLP1 was significantly increased in all DJ-1 mutant cells (Fig. 3a and b). OPA1 was only decreased significantly in D149A cells. There was no significant change of Mfn1, Mfn2 and Fis1 in all cell line we analyzed. Correlation analysis revealed that the levels of DLP1 were negatively correlated with mitochondrial aspect ratio in DJ- 1 cells (p < 0.05), suggesting that changes in the levels of DLP1 probably underlied the mitochondria morphological change.

Fig 3.

Effects of PD-associated DJ-1 mutant on mitochondrial fission/ fusion proteins. Representative immunoblot (a) and quantification analysis (b) of the expression levels of mitochondria fission and fusion proteins in M17 cell lines demonstrated significant decrease of DLP1 and Fis1 in WT cells, and significant increase of DLP1 in R98Q, D149A and L166P M17 cells compared with control or vector control cells. There was no change of other mitochondria fission and fusion proteins and mitochondrial marker protein COX IV. Equal protein amounts (10 µg) were loaded and tubulin was used as an internal loading control. All experiments were repeated three times (*p < 0.05, when compared with the control cells; one-way anova followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

PD-associated DJ-1 mutant induced mitochondria fragmentation could be completely restored by RNAi-mediated reduction of DLP1

To test whether DLP1 is causally involved in mutant DJ-1 induced mitochondrial fragmentation, we transfected all 3 clonal lines of DJ-1 R98Q, D149A and L166P cells with GFP-tagged miR RNAi expression vector targeting DLP1 (DLP1 RNAi) as we described before (Wang et al. 2009), and generated double-transgenic stable clonal cell lines. We also generated double-transgenic R98Q cells with GFP-tagged miR negative control RNAi vector (negative control) containing a scrambled sequence that did not target any known vertebrate gene. M17 cell lines stably over-expressing DLP1 RNAi vector or negative control vector described before (Wang et al. 2009) were also examined. Knocking down of DLP1 in double transgenic stable clonal cell lines was verified by immunoblot (Fig. 4a). No significant change in basal level cell death in these double transgenic lines were noted (not shown). To visualize mitochondria morphology, these cell lines were transfected with mito-DsRed2. 2 days after transfection, cells were fixed, stained and imaged by laser confocal microscopy. Consistent with our previous study, knocking down of DLP1 caused obvious mitochondrial elongation as indicated by significant increase of mitochondrial aspect ratio to 4.4 ± 0.21 (Fig. 4b and c). Expression of negative control containing the scrambled sequence has no effect on DLP1 levels and mitochondria morphology. However, DLP1 RNAi in R98Q, D149A and L166P cells significantly increased mitochondria aspect ratio to 3.7 ± 0.19, 4.0 ± 0.18 and 3.4 ± 0.22 respectively (Fig. 4b and c). Indeed, DLP1 RNAi also reduced percentage of cells with fragmented mitochondria to a level comparable to that in control cells, suggesting a complete restoration of mitochondria morphology (Fig. 4d).

Fig 4.

PD-associated DJ-1 mutant induced mitochondria fragmentation could be completely restored by RNAi-mediated reduction of DLP1. (a) Representative immunoblot confirmed the knocking down of DLP1 in double-transgenic stable clonal cell lines. Equal protein amounts (10 µg) were loaded and tubulin was used as an internal loading control. The DLP1/Tubulin ratios are all normalized to the ratio of R98Q cells, the relative level of which was set to 1. (b) Representative pictures show that knocking down of DLP1 restores PD-associated DJ-1 mutant-induced mitochondria fragmentation in double-transgenic cell lines. Blue: tubulin; red: mito-DsRed2; green: GFP. Insets represent boxed areas. Quantification of mitochondria morphology showed significant increase of aspect ratio (c) and decrease of percentage of cells displaying fragmented mitochondria (d) in PD-associated DJ-1 mutant cells also knocking down DLP1. For each cell line, at least 300 cells were analyzed in each experiment and experiments were repeated three times (*p < 0.05, when compared with the control cells; one-way anova followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

We also transiently transfected control, R98Q, D149A and L166P cells with GFP-tagged DLP1 RNAi together with mito-DsRed2, and found that similar to the stable double transgenic lines, mitochondrial fragmentation caused by PD-associated DJ-1 mutants could be completely restored by transient knocking down of DLP1 (not shown).

PD-associated DJ-1 mutant-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and cell vulnerability to stress could be rescued by RNAi-mediated reduction of DLP1

Because changes in mitochondrial morphology could affect mitochondrial function, we measured mitochondrial functional parameters including intracellular levels of ROS, ATP and mitochondria member potential (MMP) in proteins in all clonal lines of DJ-1 variants and all double transgenic lines (Fig. 5). Compared with control or vector cells, ROS levels were significantly decreased in WT DJ-1 cells, but increased in R98Q, D149A and L166P cells (Fig. 5a). Although ATP and MMP levels were unchanged in WT DJ-1 cells, they were significantly decreased in all mutant DJ-1 cells with the L166P cells demonstrating the most severe deficits (Fig. 5b and c). Interestingly, along with the blockage of mitochondrial fragmentation by DLP1 RNAi, ROS, ATP and MMP levels were restored in R98Q/DLP1 RNAi, D149A/DLP1 RNAi and L166p/DLP1 RNAi double transgenic clonal lines to the level comparable to that of control cells or vector-cells, suggesting that mutant DJ-1- induced mitochondria dysfunction was dependent on mitochondria fragmentation.

Fig 5.

PD-associated DJ-1 mutant induced mitochondrial dysfunction and cell vulnerability to stress could be rescued by RNAi-mediated reduction of DLP1. M17 cells were seeded on 96-well plates, and the intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (a), mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) (b), and ATP (c) were measured. The values are all normalized to the value obtained from control cells in the first experiment, the relative level of which was set to 100. M17 cells seeded on 96-well plates were treated with 0.75 mM H2O2 (d) or 0.5 mM MPP+ (e) for 24 h. Cell death was measured by LDH release assay. All experiments were repeated three times (*p < 0.05, when compared with the control cells; one-way anova followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

Previous study showed that over-expression of WT DJ-1 rendered neurons resistant to cell death induced by oxidative stresses and PD-specific toxins, while over-expression of PD-associated mutant DJ-1 caused neuronal death or increased neuronal susceptibility to oxidative stress and PD-specific toxins (Canet-Aviles et al. 2004; Taira et al. 2004; Zhou and Freed 2005; Deeg et al. 2010; Giaime et al. 2010). We next investigated the neuronal susceptibility to oxidative stress and PD-specific toxin in all clonal lines of DJ-1 variants and all double-transgenic lines. We found that 24-h treatment of 0.75 mM H2O2-induced significant cell death in control cells (i.e. 26 ± 2.4%) or vector cells (i.e. 27 ± 3.5%), which is blocked in WT DJ-1 cells (i.e. 6 ± 1.1%) but exacerbated in mutant DJ-1 expressing cells (i.e. 52 ± 6.2% in R98Q cells, 45 ± 5.4% in D149A cells and 79 ± 8.4% in L166P cells). Similarly, 24-h treatment of 0.5 mM MPP+ also caused significant cell death in control cells (18 ± 2.2%) or vector cells (16 ± 2.0%), which is inhibited in WT DJ-1 cells and enhanced in mutant DJ-1 cells (44 ± 7.4% in R98Q cells, 37 ± 7.2% D149A cells, and 69 ± 9.1% in L166P cells). Notably, either H2O2- or MPP+-induced cell death was completely prevented in R98Q/DLP1 RNAi, D149A/DLP1 RNAi and L166P/DLP1 RNAi double transgenic, suggesting that inhibition of PD-associated DJ-1 mutant-induced mitochondrial fragmentation almost completely prevented PD-associated DJ-1 mutant-induced vulnerability to stress.

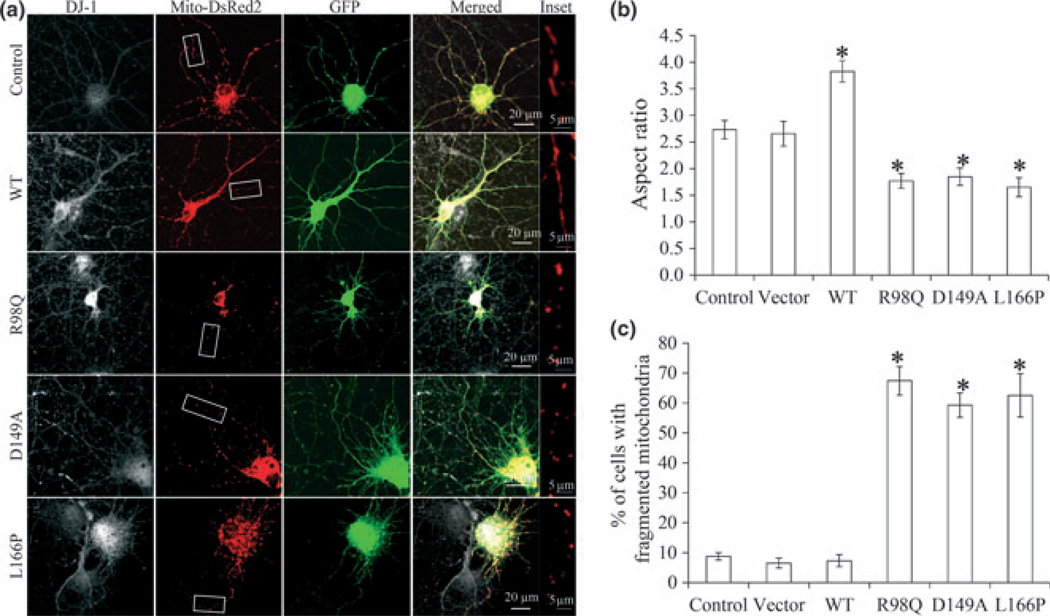

PD-associated DJ-1 mutant-induced mitochondrial fragmentation in primary neurons

To determine whether PD-associated DJ-1 mutants have similar effect on mitochondria in well-differentiated neuronal cells, rat E18 primary cortical neurons (DIV = 7) were transiently co-transfected with V5-tagged wild-type DJ-1 or PD-associated DJ-1 R98Q, D149A and L166P mutants and mito-DsRed2 at a ratio of 3:1. Two days after transfection, neurons were fixed, stained and imaged by laser confocal microscopy. Positively co-transfected cells were selected by the presence of both DJ-1 staining and DsRed2 fluorescence (Fig. 6a). No difference in viability of control cells and transfected cells were noted 2 days after transfection. As expected, most control neurons or empty vector transfected neurons (> 90%) demonstrated heterogeneous but predominantly tubular mitochondrial morphology with mitochondrial aspect ratio of 2.7 ± 0.17. Over-expression of WT DJ-1 significantly increased mitochondria aspect ratio to 3.8 ± 0.2. On the contrary, mitochondria aspect ratio was significantly reduced to 1.8 ± 0.14, 1.8 ± 0.16 and 1.6 ± 0.18 in neurons over-expressing R98Q, D149A and L166P respectively (Fig. 6b). The percentage of neurons with fragmented mitochondria was also significantly increased in neurons over-expressing R98Q, D149A and L166P (Fig. 6c).

Fig 6.

PD-associated DJ-1 mutant induced mitochondrial fragmentation in primary neurons. Rat E18 primary cortical neurons (DIV = 7) were transiently co-transfected with empty vector or V5 tagged DJ-1 (WT, R98Q, D149A and L166P), GFP and mito-DsRed2 at a ratio of 3 : 1 : 1. Two days after transfection, neurons were fixed, stained with DJ-1 and imaged by laser confocal microscopy. Representative images (a) and quantification of mitochondria morphology (b, c) in primary neurons transfected with indicated plasmids. Boxed areas enlarged immediately below. White: DJ-1; green: GFP; red: mito-DsRed2. At least 20 cells were measured analyzed in each experiment and experiments were repeated three times (*p < 0.05, when compared with the control cells; one-way anova followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

Discussion

In this study, we focused on the effects of PD-associated DJ- 1 mutants on mitochondrial dynamics and function in M17 neuronal cells and primary cortical neurons. We used confocal microscopy and electron microscopy to demonstrate that over-expression of various pathogenic DJ-1 mutants causes significant mitochondrial fragmentation. In association with these mitochondrial morphological defects, mitochondria had impaired bioenergetics and increased vulnerability to H2O2- and MPP+. We also demonstrated that neurons over-expressing WT DJ-1 had significantly elongated mitochondria which likely mediate their enhanced resistance to H2O2- and MPP+.

The major finding of this study is that DJ-1 is involved in the regulation of mitochondrial dynamics. On one hand, over-expression of various pathogenic DJ-1 mutants causes mitochondrial fragmentation and structural damage in neurons. Because pathogenic DJ-1 mutations cause autosomal recessive PD due to a loss of protein function, this finding is consistent with other studies reporting that DJ-1 deficiency produces a fragmented mitochondrial phenotype (Irrcher et al. 2010; Krebiehl et al. 2010; Thomas et al. 2011). Fragmented mitochondria were also identified in human fibroblasts from DJ-1 E64D PD patients or lymphoblasts isolated from DJ-1 L166P or deletion mutation-caused PD patients (Irrcher et al. 2010; Krebiehl et al. 2010) although it should be noted that mitochondrial morphology abnormalities caused by pathogenic proteins may not always be consistent between peripheral cells and neurons (Mortiboys et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2008a,b, 2011a; Lutz et al. 2009). On the other hand, we also demonstrated that over-expression of WT DJ-1 causes mitochondrial elongation. This novel finding implicates that DJ-1 may be actively involved in the inhibition of mitochondrial fission or enhancement of mitochondrial fusion. Given the abundant and ubiquitous expression of DJ-1, it is possible that DJ-1 may play a previously unrecognized major role in maintaining appropriate steady-state mitochondrial dynamic and network in neurons. In support of such a notion, it is of interest to note the importance of the synergistic transcriptional activity of DJ-1 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1α) in general mitochondrial maintenance (Zhong and Xu 2008). Prior studies reported that while DJ-1 expression could prevent toxin-induced mitochondrial fragmentation, DJ-1 expression alone had no effect on mitochondrial morphology in M17 cells (Thomas et al. 2011). This is likely due to different methods used because a transient transfection was employed and mitochondrial morphology/connectivity was indirectly measured by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching in prior studies (Thomas et al. 2011). The use of stable cell lines in this study enabled us to directly measure mitochondrial length in addition to confocal characterization of mitochondrial morphology which likely gives a more definite answer. These results were not due to clonal effect because multiple stable clonal lines were used.

Mitochondrial morphology is determined by the balance between mitochondrial fission and fusion. Mitochondrial elongation phenotype could be due to enhanced fusion, reduced fission or both and mitochondrial fragmentation could be due to excessive fission, reduced fusion or both. It is known that reduced expression of DLP1, the fission protein, causes mitochondrial elongation while increased DLP1 causes mitochondrial fragmentation. We found that changes in the expression levels of DLP1 were consistent with changes in mitochondrial morphology in DJ-1 expressing cells: DLP1 expression is reduced in cells over-expressing WT DJ-1 where mitochondria became elongated and DLP1 expression is consistently increased in all the cell lines expressing pathogenic DJ-1 mutants where mitochondria became fragmented. These findings suggest that DJ-1 could modulate DLP1 expression and DLP1-dependent fission likely plays a major role in mediating the effect of DJ-1 on mitochondrial morphology. DJ-1acts as a transcriptional regulator of antioxidant gene batteries and it also regulates protein stability and degradation through sumoylation and ubiquitination (Zhong et al. 2006; Xiong et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2011c). Therefore, it is worth investigating how DJ-1 may affect DLP1 expression at multiple levels. Although no changes in mitochondrial fusion proteins were identified, it does not necessarily exclude the involvement of reduced fusion in DJ-1 mutant-induced mitochondrial fragmentation. Based on the premise that oxidative stress causes mitochondrial fragmentation (Barsoum et al. 2006) and the finding that antioxidants rescue mitochondrial morphology in DJ-1 deficient cells DJ-1 acts in parallel to the PINK1/parkin pathway to control mitochondrial function and autophagy (Thomas et al. 2011), previous studies suggest that oxidative stress is likely an important factor triggering mitochondrial phenotype in DJ-1 deficient cells (Thomas et al. 2011). As hydrogen peroxide decreased DLP1 expression (Wang et al. 2008a), it is likely oxidative stress induces mitochondrial fragmentation by inhibiting fusion. In fact, it was demonstrated that DJ-1 deficiency impaired the mitochondrial fusion process (Thomas et al. 2011). Nevertheless, as excessive mitochondrial fission also leads to increased ROS generation (Yu et al. 2006), the causal involvement of oxidative stress and its downstream mechanism mediating DJ-1 deficiency-induced mitochondrial fragmentation remains to be determined. It is also of interest to investigate whether DJ-1, as a redox sensor and/or antioxidant protein, exerts these functions by modulating the balance between mitochondrial fission and fusion. Several DJ-1 interacting proteins including Bcl-xL and mortalin also modulate mitochondrial dynamics potentially through direct interaction with DLP1, it is therefore possible that DJ-1 may indirectly modulate mitochondrial dynamics through these adaptor proteins (Li et al. 2008; Burbulla et al. 2010; Ren et al. 2011). Nevertheless, given that DJ-1 is also localized to mitochondria (Canet-Aviles et al. 2004), it is also possible that DJ-1 may directly interact with mitochondrial fission/ fusion machinery and affect mitochondria morphology/ function.

In additional to mitochondrial fragmentation, structural damage to mitochondria was also identified in cells over-expressing pathogenic DJ-1 mutants, which is consistent with impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics and function in these cells. In fact, our electron microscopy revealed that L166P mutant caused more severe mitochondrial structural damage which correlates with more severe toxic effects on mitochondrial functional parameters and susceptibility to H2O2- or PD-toxin MPP+, suggesting that L166P probably has more potent effect, which is consistent with previous study showing that L166P mutation leads to the most severe and global destabilization and unfolding of the protein structure comparing to other pathogenic mutations (Malgieri and Eliezer 2008). DLP1 knockdown restored mitochondrial morphology and also almost completely restored ROS levels, mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP levels, suggesting that mitochondrial fragmentation underlies mitochondrial dysfunction induced by DJ-1 mutations. Over-expression of pathogenic DJ-1 mutants caused increased vulnerability to H2O2- or PD-toxin MPP+, which could also be completely prevented by DLP1 knockdown and blockage of mitochondrial fragmentation, suggesting that excessive mitochondrial fragmentation mediates toxic effects of DJ-1 mutations and inhibition of mitochondria fission or enhancement of fusion could have beneficial effects. In this regard, it is likely that enhanced mitochondrial fusion in neurons over-expressing WT DJ-1 underlies the beneficial effect of WT DJ-1 against H2O2- or MPP+.

Overall, we demonstrated that WT DJ-1 causes mitochondrial elongation which likely underlies its neuroprotective effects. In contrast, PD-associated DJ-1 mutants cause mitochondrial fragmentation which mediates their toxic effect on mitochondrial function and increased susceptibility to stressors. DJ-1 modulation on the expression of DLP1 likely plays a major role in mediating the effect of DJ-1 on mitochondrial morphology.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Dr Robert M. Kohrman Memorial Fund, the National Institutes of Health (R21 NS071184 to XZ) and the American Parkinson’s Disease Association.

Abbreviations used

- DLP1

dynamin-like protein

- Mfn1/2

mitofusin 1/2

- MMP

mitochondria member potential

- MPP+

1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium

- OPA1

optic atrophy 1

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PINK1

PTEN-induced kinase 1

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

- Bandyopadhyay S, Cookson MR. Evolutionary and functional relationships within the DJ1 superfamily. BMC Evol. Biol. 2004;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsoum MJ, Yuan H, Gerencser AA, et al. Nitric oxide-induced mitochondrial fission is regulated by dynamin-related GTPases in neurons. EMBO J. 2006;25:3900–3911. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindoff LA, Birchmachin MA, Cartlidge NEF, Parker WD, Turnbull DM. Respiratory-chain abnormalities in skeletal-muscle from patients with Parkinsons-disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 1991;104:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(91)90311-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifati V, Rizzu P, van Baren MJ, et al. Mutations in the DJ-1 gene associated with autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism. Science. 2003;299:256–259. doi: 10.1126/science.1077209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckman TD, Chang R, Sutphin MS, Eiduson S. Interaction of 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion with human-platelets. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Co. 1988;151:897–904. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80366-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbulla LF, Schelling C, Kato H, et al. Dissecting the role of the mitochondrial chaperone mortalin in Parkinson’s disease: functional impact of disease-related variants on mitochondrial homeostasis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:4437–4452. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canet-Aviles RM, Wilson MA, Miller DW, et al. The Parkinson’s disease protein DJ-1 is neuroprotective due to cysteine-sulfinic acid-driven mitochondrial localization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:9103–9108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402959101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark IE, Dodson MW, Jiang CG, Cao JH, Huh JR, Seol JH, Yoo SJ, Hay BA, Guo M. Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature. 2006;441:1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/nature04779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson MR. DJ-1, PINK1, and their effects on mitochondrial pathways. Mov. Disord. 2010;25:S44–S48. doi: 10.1002/mds.22713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeg S, Gralle M, Sroka K, Bahr M, Wouters FS, Kermer P. BAG1 restores formation of functional DJ-1 L166P dimers and DJ-1 chaperone activity. J. Cell Biol. 2010;188:505–513. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng HS, Dodson MW, Huang HX, Guo M. The Parkinson’s disease genes pink1 and parkin promote mitochondrial fission and/or inhibit fusion in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14503–14508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803998105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detmer SA, Chan DC. Functions and dysfunctions of mitochondrial dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:870–879. doi: 10.1038/nrm2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaime E, Sunyach C, Druon C, et al. Loss of function of DJ-1 triggered by Parkinson’s disease-associated mutation is due to proteolytic resistance to caspase-6. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:158–169. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg MS, Pisani A, Haburcak M, et al. Nigrostriatal dopaminergic deficits and hypokinesia caused by inactivation of the familial Parkinsonism-linked gene DJ-1. Neuron. 2005;45:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irrcher I, Aleyasin H, Seifert EL, et al. Loss of the Parkinson’s disease-linked gene DJ-1 perturbs mitochondrial dynamics. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:3734–3746. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junn E, Jang WH, Zhao X, Jeong BS, Mouradian MM. Mitochondrial localization of DJ-1 leads to enhanced neuroprotection. J. Neurosci. Res. 2009;87:123–129. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim RH, Smith PD, Aleyasin H, et al. Hypersensitivity of DJ-1-deficient mice to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyrindine (MPTP) and oxidative stress. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:5215–5220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501282102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman WJ, Distelmaier F, Esseling JJ, Smeitink JA, Willems PH. Computer-assisted live cell analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential, morphology and calcium handling. Methods. 2008;46:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebiehl G, Ruckerbauer S, Burbulla LF, et al. Reduced basal autophagy and impaired mitochondrial dynamics due to loss of Parkinson’s disease-associated protein DJ-1. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston JW, Ballard P, Tetrud JW, Irwin I. Chronic Parkinsonism in humans due to a product of meperidine-analog synthesis. Science. 1983;219:979–980. doi: 10.1126/science.6823561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Chen Y, Jones AF, et al. Bcl-xL induces Drp1-dependent synapse formation in cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:2169–2174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711647105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas JI, Marin I. A new evolutionary paradigm for the Parkinson disease gene DJ-1. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:551–561. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz AK, Exner N, Fett ME, et al. Loss of parkin or PINK1 function increases Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:22938–22951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.035774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malgieri G, Eliezer D. Structural effects of Parkinson’s disease linked DJ-1 mutations. Protein Sci. 2008;17:855–868. doi: 10.1110/ps.073411608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann VM, Cooper JM, Krige D, Daniel SE, Schapira AH, Marsden CD. Brain, skeletal muscle and platelet homogenate mitochondrial function in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 1992;115(Pt 2):333–342. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortiboys H, Thomas KJ, Koopman WJ, et al. Mitochondrial function and morphology are impaired in parkin-mutant fibroblasts. Ann. Neurol. 2008;64:555–565. doi: 10.1002/ana.21492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounsey RB, Teismann P. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: pathogenesis and neuroprotection. Parkinsons Dis. 2010;2011:617472. doi: 10.4061/2011/617472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterna JC, Leng A, Weber E, Feldon J, Bueler H. DJ-1 and Parkin modulate dopamine-dependent behavior and inhibit MPTP-induced nigral dopamine neuron loss in mice. Mol. Ther. 2007;15:698–704. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole AC, Thomas RE, Andrews LA, McBride HM, Whitworth AJ, Pallanck LJ. The PINK1/Parkin pathway regulates mitochondrial morphology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:1638–1643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709336105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren H, Fu K, Wang D, Mu C, Wang G. Oxidized DJ-1 interacts with the mitochondrial protein BCL-XL. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:35308–35317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.207134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober A. Classic toxin-induced animal models of Parkinson’s disease 6-OHDA and MPTP. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:215–224. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0938-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira T, Saito Y, Niki T, Iguchi-Ariga SMM, Takahashi K, Ariga H. DJ-1 has a role in antioxidative stress to prevent cell death. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:213–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KJ, McCoy MK, Blackinton J, et al. DJ-1 acts in parallel to the PINK1/parkin pathway to control mitochondrial function and autophagy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:40–50. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Su B, Fujioka H, Zhu X. Dynamin-like protein 1 reduction underlies mitochondrial morphology and distribution abnormalities in fibroblasts from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease patients. Am. J. Pathol. 2008a;173:470–482. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Su B, Siedlak SL, Moreira PI, Fujioka H, Wang Y, Casadesus G, Zhu X. Amyloid-beta overproduction causes abnormal mitochondrial dynamics via differential modulation of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008b;105:19318–19323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804871105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Su B, Lee HG, Li X, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. Impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:9090–9103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Song P, Du L, et al. Parkin ubiquitinates Drp1 for proteasome-dependent degradation: implication of dysregulated mitochondrial dynamics in Parkinson disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2011a;286:11649–11658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.144238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Su B, Liu W, He X, Gao Y, Castellani RJ, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. DLP1-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation mediates 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium toxicity in neurons: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Aging Cell. 2011b;10:807–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Liu J, Chen S, et al. DJ-1 modulates the expression of Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase-1 through the Erk1/2-Elk1 pathway in neuroprotection. Ann. Neurol. 2011c;70:591–599. doi: 10.1002/ana.22514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong H, Wang D, Chen L, et al. Parkin, PINK1, and DJ-1 form a ubiquitin E3 ligase complex promoting unfolded protein degradation. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:650–660. doi: 10.1172/JCI37617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T, Robotham JL, Yoon Y. Increased production of reactive oxygen species in hyperglycemic conditions requires dynamic change of mitochondrial morphology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:2653–2658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511154103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong N, Xu J. Synergistic activation of the human MnSOD promoter by DJ-1 and PGC-1alpha: regulation by SUMOylation and oxidation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:3357–3367. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong N, Kim CY, Rizzu P, Geula C, Porter DR, Pothos EN, Squitieri F, Heutink P, Xu J. DJ-1 transcriptionally upregulates the human tyrosine hydroxylase by inhibiting the sumoylation of pyrimidine tract-binding protein-associated splicing factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:20940–20948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Freed CR. DJ-1 up-regulates glutathione synthesis during oxidative stress and inhibits A53T alpha-synuclein toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:43150–43158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507124200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Chu CT. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl. 2):S325–S334. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]