Abstract

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a kind of inflammatory hyperplasia seen in the oral cavity. This term is a misnomer because the lesion is unrelated to infection. In reality it arises in response to various stimuli such as low-grade local irritation, traumatic injury or hormonal factors. It predominantly occurs in the second decade of life in young females possibly because of the vascular effects of female hormones. It is also called as pregnancy tumor because of its high frequency of occurrence during the early part of pregnancy. Even though, this lesion is non-neoplastic and treatment procedure is simple, it should be diagnosed correctly before proceeding with the treatment. The most common site for PGs is gingiva (75%) and rarely in the palate. In this case report, we are going to present very rare occurrence of pregnancy tumor in the hard palate.

KEY WORDS: Inflammatory hyperplasia, oral cavity, pregnancy tumor, pyogenic granuloma

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a common tumor-like growth of the oral cavity or skin that is considered to be non-neoplastic[1] inflammatory hyperplasia. The term “inflammatory hyperplasia” is used to describe a large range of nodular growth of the oral mucosa that histologically represents inflamed fibrous and granulomatous tissues[2] such as epulis fissuratum, palatal papillary hyperplasia, pregnancy tumor and PG.

The term “PG” is a misnomer because the lesion neither contains pus nor strictly granulation.[1,3,4] This term was introduced by Hartzell in 1904. It commonly occurs in the oral cavity and usually considered to be a reactive tumor like lesion, which arises in response to various stimuli such as a chronic low grade local irritation, local injury, hormonal factors or certain kind of drugs. Although PG may occur in all ages, it is predominant in the second decade of life in young adult females, possibly because of the vascular effects of female hormones.[5,6]

During pregnancy, the changes in the hormonal level exaggerate the response to local irritants, which leads to the formation of pregnancy tumor. Nearly, 75% of oral PG occurs in the gingiva. The lips, tongue and buccal mucosa are the next most common sites[1] and rarely in the palatal region.

Case Report

A 22-year-old female patient reported to the Department of Oral medicine and Radiology, with a complaint of growth in the palate for the past 8 months. History reveals that the growth started as a small nodular, which gradually increased to the present size. Patient gives a history of occasional bleeding from the lesion and her medical history reveals that she developed growth during her 2nd month of pregnancy and it has retained after pregnancy.

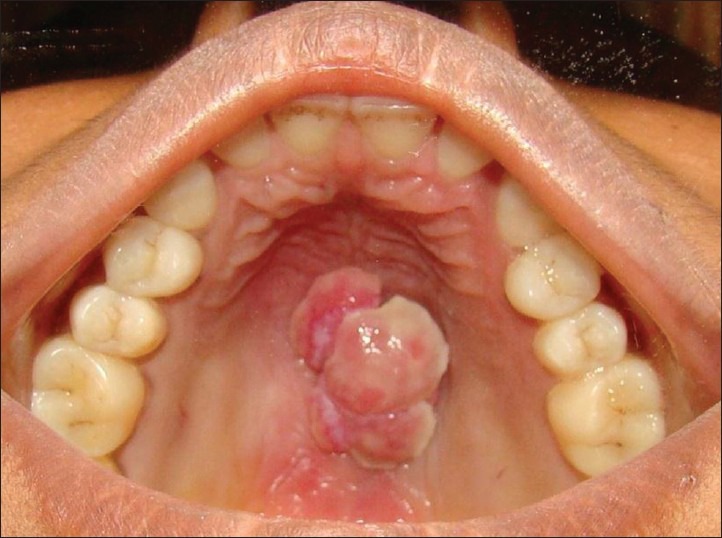

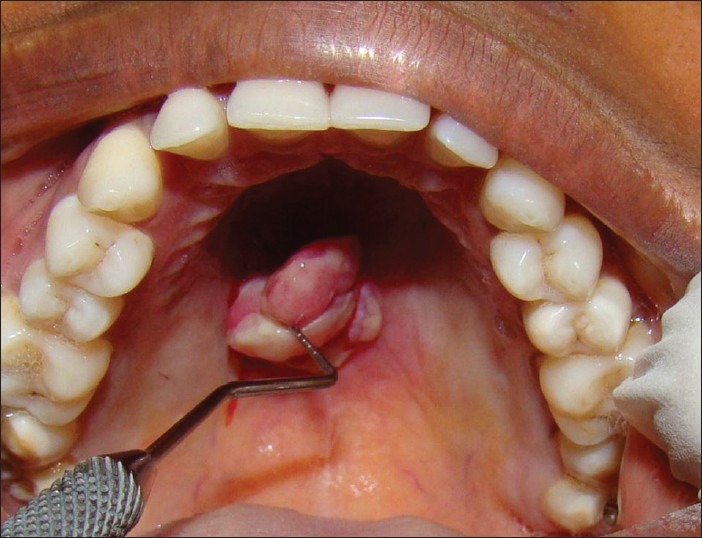

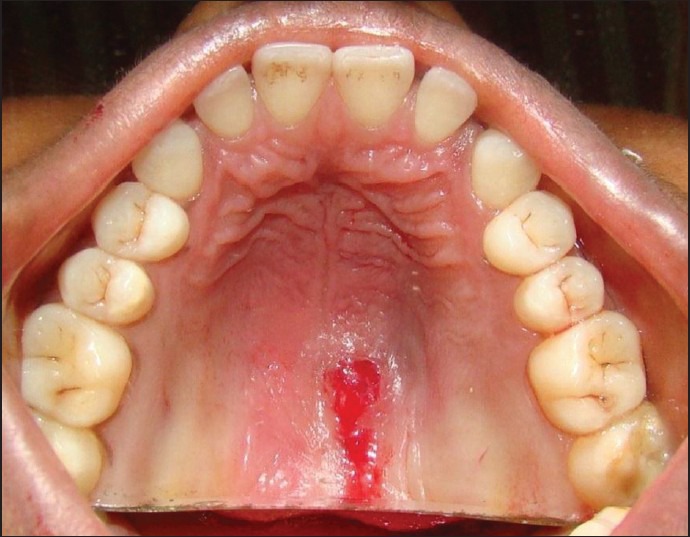

On intra oral examination multiple, well-defined, pedunculated growth is evident in the midpalatal region [Figure 1], measuring around 2 cm × 2 cm in size, irregular margins, surface lobulated and color appears purplish red and certain parts of the lesion are blanched. The growth is firm in consistency, non-tender, smooth surface and has a narrow pedunculated base with evidence of bleeding from the base of the lesion [Figure 2]. Excision biopsy was carried out under local anesthesia and specimen [Figures 3 and 4] sent for histopathological study. Histopathological study confirmed it as PG. On 3 months follow-up, healing was satisfactory and there was no recurrence.

Figure 1.

Lobulated fibrous growth seen on midpalatal region

Figure 2.

Pedenculated growth and bleeding on palpation

Figure 3.

Excised specimen

Figure 4.

Post excision view

Histopathological report

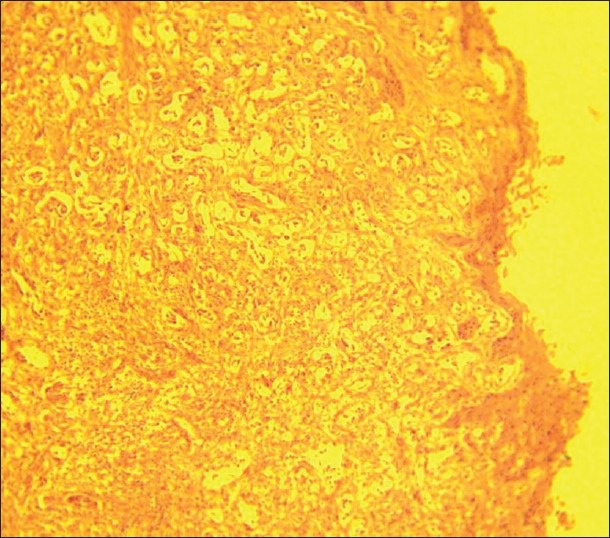

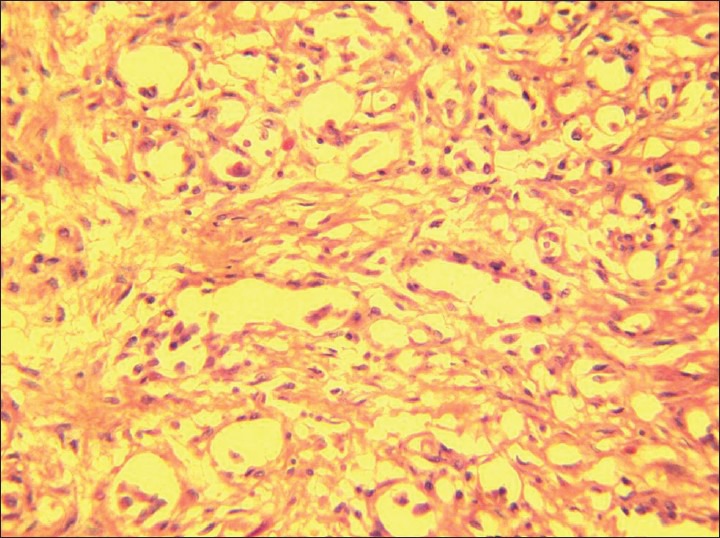

On microscopic examination, sections show stratified squamous epithelium with ulceration overlying lobules of proliferating vascular channels amidst inflammatory cells. The impression about the lesion was consistent with lobular capillary hemangioma PG [Figures 5 and 6].

Figure 5.

Histopathological view of lobular capillary haema-ngioma (pyogenic granuloma)

Figure 6.

Large vessel lobule surrounded by small capillaries

Discussion

Poncet and Dor in 1897 first described about PG in their review. PGs originally thought to represent a fungal infection (Botryomycosis), but later it was suggested that they might occur as a reactive inflammatory process associated with exuberant fibro vascular proliferation of the connective tissue secondary to trauma and infection. The PGs are typically pedunculated or sessile and smooth or lobulated. It will occur in any age, with the peak in the third decade of life.[2] The female predominance is 1.5:1 in the female-male occurrence ratio. The hormones progesterone and estrogen influence the growth to grow faster and explains the high incidence in women, particularly pregnant and oral contraceptive consumers.[7,8]

During pregnancy, nearly 5% of the pregnant women develop PG[6] most commonly in the gingiva and rarely in the palate. Hence, the terms “pregnancy tumor and granuloma gravidarum” are often used.[1] The hormonal imbalance coincides with pregnancy, heightens the organism's response to irritation.[9] However, bacterial plaque, trauma and gingival inflammation are necessary for sub-clinical hormone alterations leading to gingivitis.[10,11] Sometimes pregnancy gingivitis can show a tendency toward localized hyperplasia, which is called pregnancy granuloma. In general, it appears in second to third month of pregnancy, with the tendency to bleed and a possible interference with mastication.[8]

The molecular mechanism behind the development and regression of PG during pregnancy is the profound upheaval of hormones (Estrogen and Progesterone), which is frequently associated with changes in the function and structure of the blood and lymph microvasculature of the skin and mucosa. Estrogen accelerates wound healing by stimulating nerve growth factor, production of macrophages and granulocyte-macrophage-colony stimulating factor. Production of keratinocytes, basic fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor-β1 and fibroblasts leads to granulation tissue formation. On the other hand, progesterone functions as an immunosuppressant in the gingival tissues of pregnant women, preventing rapid acute inflammatory reaction against plaque, but allowing an increased chronic tissue reaction resulting clinically in an exaggerated appearance of inflammation. The molecular mechanism for regression of pregnancy PG after delivery remains unclear. It has been proposed that in the absence of endothelial growth factor and angiopoitin-2 the blood vessels regress, which might be the reason for regression of PG after delivery.

When a growth is found in the oral cavity, it is important to formulate a differential diagnosis since this would help further evaluation of the condition and management of the patient. Biopsy findings have an important role and are definitive in establishing the diagnosis. Differential diagnosis of palatal PG includes peripheral giant cell granuloma,[12] peripheral ossifying fibroma,[1,12] metastatic cancer,[12] hemangioma,[12] pregnancy tumor[1,8] and angiosarcoma.[1] In some cases, the lesion usually shrinks after delivery and makes surgery unnecessary.[6] However, in some cases, if there is excessive growth or disturbing mastication may require surgical intervention, which can be carried out during the 2nd trimester. After excision, recurrence occurs in up to 16% of the lesions. Hence, in some cases, re-excision is necessary.[10] During pregnancy, hormonal imbalance plays an important role in formation of PG. Hence maintenance of good oral hygiene, removal of dental plaque and use of soft toothbrushes are important to avoid the occurrence of PG.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Greenberg MS, Glick M, Jonathan A. 11th ed. Hamilton: BC Decker; 2008. Burket's Oral Medicine; pp. 133–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akyol MU, Yalçiner EG, Doğan AI. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma) of the tongue. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;58:239–41. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(01)00425-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epivatianos A, Antoniades D, Zaraboukas T, Zairi E, Poulopoulos A, Kiziridou A, et al. Pyogenic granuloma of the oral cavity: Comparative study of its clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features. Pathol Int. 2005;55:391–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2005.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ragezi JA, Sciubba JJ. 5th ed. Gurgaon: Elsevier; 2009. Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathological Correlations; pp. 111–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mussalli NG, Hopps RM, Johnson NW. Oral pyogenic granuloma as a complication of pregnancy and the use of hormonal contraceptives. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1976;14:187–91. doi: 10.1002/j.1879-3479.1976.tb00592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neville BW, Allen CM, Douglas DD, Bouquot JE. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology; pp. 447–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sills ES, Zegarelli DJ, Hoschander MM, Strider WE. Clinical diagnosis and management of hormonally responsive oral pregnancy tumor (pyogenic granuloma) J Reprod Med. 1996;41:467–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sooriyamoorthy M, Gower DB. Hormonal influences on gingival tissue: Relationship to periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:201–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1989.tb01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ojanotko-Harri AO, Harri MP, Hurttia HM, Sewón LA. Altered tissue metabolism of progesterone in pregnancy gingivitis and granuloma. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:262–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vilmann A, Vilmann P, Vilmann H. Pyogenic granuloma: Evaluation of oral conditions. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;24:376–82. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(86)90023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esmeili T, Lozada-Nur F, Epstein J. Common benign oral soft tissue masses. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49:223–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood NK, Goaz PW. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997. Differential Diagnosis of Oral and Maxillofacial Lesions; pp. 549–50. [Google Scholar]