Abstract

Myiasis is a rare disease primarily caused by the invasion of tissue by larvae of certain dipteran flies. Oral myiasis is still more “rare” and “unique” owing to the fact that oral cavity rarely provides the necessary habitat conducive for a larval lifecycle. Common predisposing factors are poor oral hygiene, halitosis, trauma, senility, learning disabilities, physically and mentally challenged conditions. Oral myiasis can lead to rapid tissue destruction and disfigurement and requires immediate treatment. Treatment consists of manual removal of maggots from the oral cavity after application of chemical agents. Good sanitation, personal and environmental hygiene and cleanliness and special care for debilitated persons are the best methods to prevent oral myiasis. This case report describes the presentation of oral myiasis caused by musca nebulo (common house fly) in a 40-year-old male patient, with recent maxillofacial trauma. The patient was treated by manual removal larvae by topical application of turpentine oil, followed by surgical debridement of the wound and open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture.

KEY WORDS: Internal fixation, oral myiasis, open reduction, turpentine oil

Myiasis is derived from a Latin word “Muia,” which means fly and “iasis,” which means disease. The term was coined by Hope in 1840 and defined by Zumpt. It is a pathological condition in which there is an infestation of living mammals with the dipterous larvae, which, at least for a certain period feed on the host's dead or living tissue and develop as parasites.[1]

The term myiasis refers to infestation of living tissues of animals or humans by diptera larvae. The species of flies that cause myiasis are Cochiliomyia hominivorax, known as the screw worm fly, Dermatobia hominis or human botfly, Sacrophagidae species, Alouttamyia baeri and Anastrepha species family. Myiasis can be classified clinically as primary (larvae feed on the living tissue) and secondary (larvae feed on dead tissue). Depending on the condition of the involved tissue it is classified into accidental myiasis (larvae ingested along with food), semi-specific myiasis (larvae laid on necrotic tissue in wounds) and obligatory myiasis (larvae affecting undamaged skin). Further classification can be based on the site as cutaneous, external orifice, internal organs and generalized. The most common anatomic sites for myiasis are the nose, eye, lung, ear, anus, vagina and more rarely, the mouth. Incidence of oral myiasis as compared to that of cutaneous myiasis is less as the oral tissues are not permanently exposed to the external environment.[2]

Case Report

A 40-year-old male patient with maxillofacial trauma reported to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery with a chief complaint of inability to close the mouth and difficulty in chewing the food. History revealed trauma 3 days back due to physical assault.

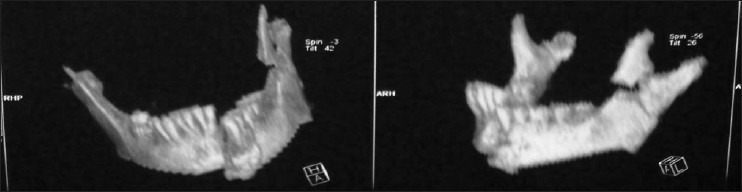

On clinical examination, patient had a laceration of upper lip and palatal mucosa [Figure 1]. He also had a posterior open bite. In addition, patient had a very poor oral hygiene [Figure 2]. Further, there were multiple maggots crawling out from the lacerated palatal mucosal wound. Orthopantamogram and computed tomography scan showed a fracture of left parasymphysis, bilateral condyle and left coronoid fracture [Figure 3]. After obtaining a detailed case history, clinical, radiographic and hematological investigations, a diagnosis of maxillofacial trauma with oral myiasis was made. The patient was planned for open reduction and internal fixation for fracture and manual removal of maggots under general anesthesia.

Figure 1.

Intra oral photograph showing laceration in palate and upper lip

Figure 2.

Intra oral photograph showing disturbed occlusion

Figure 3.

Pre-operative computed tomography scan

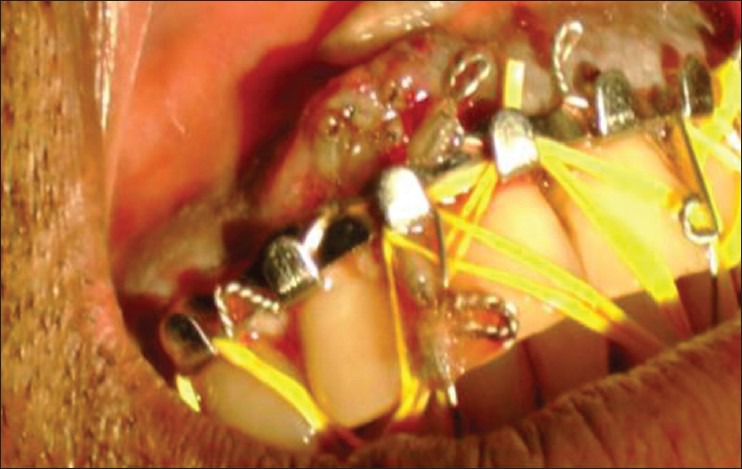

Cotton bud impregnated with turpentine oil was applied to the lacerated mucosa for a minimum of 10-12 min. After these maggots were manually removed with the help of blunt tweezer and curved forceps and then sent for entomological examinations [Figures 4 and 5]. Further management included surgical removal of necrotic tissue slough present and irrigating the area with saline, H2O2 and then with betadine followed by metronidazole. After debridement of the region, intermaxillary fixation with plating was done in parasymphysis and condylar region [Figure 6]. The patient was put on tablet Ivermectin 6 mg OD for 5 days along with antibiotic cover of doxycycline 100 mg BD and Metronidazole 100 ml 8 h given for 5 days. The patient was advised to maintain proper oral hygiene and rinse the wound with 0.2% Chlorhexidine mouthwash, 3 to 4 times daily.

Figure 4.

Intra oral debridement of the lesion

Figure 5.

Intraoral photograph showing maggots

Figure 6.

Maxillomandibular fixation

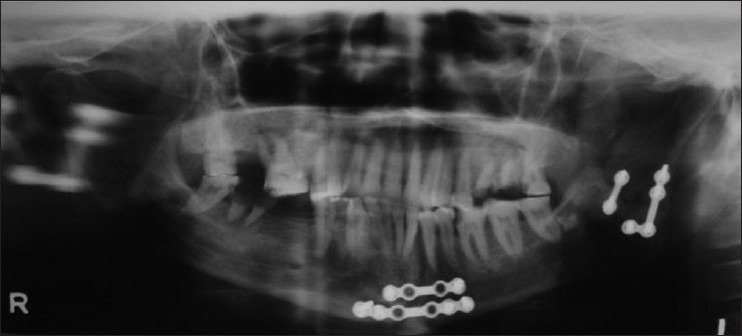

All maggots were removed including dead larvae in approximately 2 days. Patient was discharged on 4th day after informing about wound care. Follow-up appointment was given. Extra oral sutures were removed and patient was recalled periodically. On the 14th day wound had healed completely [Figures 7 and 8]. Lab analysis report of maggots, described it as house fly (musca nebulo) common Indian house fly.

Figure 7.

Post-operative orthopantomograph

Figure 8.

Post-operative intraoral photograph

Discussion

Myiasis is a rare condition in human beings although frequently reported in vertebrate animals, main parasites being flies of order of diptera (maggots), which feed on the host's dead or living tissue. In this condition, the soft-tissue parts of the oral cavity are invaded by parasitic larvae of these flies. Hope et al., described the first incidence of this parasitosis in 1840, common infestations being reported in open wounds and dead tissues; but, cavities such as ears, nose and oral cavity may be involved. This parasitic infestation commonly seen in mouth breathers, alcoholism, senility, in oral and maxillofacial traumas or in old age groups especially mentally handicapped persons. Low socio-economic status, immunocompromised state, debilitated and unhygienic living conditions may also act as predisposing factors.

Diagnosis of oral myaisis is usually made by the clinical picture of pulsating larvae. The traditional management of oral myaisis is mechanical removal using hemostats or ordinary clinical pincers. Larvae rupture must be avoided. When there are multiple larvae, extensive tissue destruction or in an advanced stage of development of larva as in the present case, adjuvant measures like treating the area with ether or comparable solvents are advocated in literatures, which irritate the maggots causing larval asphyxia and forcing them out of their hiding place. Local application of several substances such as oil of turpentine, mineral oil, ether, chloroform, ethyl chloride, mercuric chloride, creosote, saline, phenol, calomel, olive oil, iodoform, can be used to ensure complete removal of larvae. Male predilection of occurrence has been noted in most literatures because of their more outdoor activities and neglecting the oral hygiene when compared to the female counterpart.[3]

Ivermectin, a semi – synthetic macrolide antibiotic, is found safe for human use as proposed by Shinohara et al. and Osorio et al. In some cases, it shows multiple site involvement. In such cases, semi – synthetic chemotherapy is indicated. Secondary bacterial infection along the surrounding skin should be treated with antibiotics.[4,5,6] Patient's diet should be supplemented with multivitamins, mineral and nutrients.[4]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kumar P, Srikumar GP. Oral myiasis in a maxillofacial trauma patient. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3:202–4. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.96830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma A. Oral Myiasis is a Potential Risk in Patients with Special Health Care Needs. J Glob Infect Dis. 2012;4:60–1. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.93763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar SL, Manuel S, John TV, Sivan MP. Extensive gingival myiasis-Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2011;15:340–3. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.86715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pereira T, Tamgadge AP, Chande MS, Bhalerao S, Tamgadge S. Oral myiasis. Contemp Clin Dent. 2010;1:275–6. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.76401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatt AP, Jayakrishnan A. Oral myiasis: A case report. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2000;10:67–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2000.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma A, Hedge A. Primary oral myiasis due to Chrysomya bezziana treated with Ivermectin. A case report. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2010;34:259–61. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.34.3.6ntr2w7416934641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]