Abstract

The increasing incidence of type 1 diabetes (T1D) and autoimmune diseases in industrialized countries cannot be exclusively explained by genetic factors. Human epidemiological studies and animal experimental data provide accumulating evidence for the role of environmental factors, such as infections, in the regulation of allergy and autoimmune diseases. The hygiene hypothesis has formally provided a rationale for these observations, suggesting that our co-evolution with pathogens has contributed to the shaping of the present-day human immune system. Therefore, improved sanitation, together with infection control, has removed immunoregulatory mechanisms on which our immune system may depend. Helminths are multicellular organisms that have developed a wide range of strategies to manipulate the host immune system to survive and complete their reproductive cycles successfully. Immunity to helminths involves profound changes in both the innate and adaptive immune compartments, which can have a protective effect in inflammation and autoimmunity. Recently, helminth-derived antigens and molecules have been tested in vitro and in vivo to explore possible applications in the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, including T1D. This exciting approach presents numerous challenges that will need to be addressed before it can reach safe clinical application. This review outlines basic insight into the ability of helminths to modulate the onset and progression of T1D, and frames some of the challenges that helminth-derived therapies may face in the context of clinical translation.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes, hygiene hypothesis, NOD, Treg cell, dendritic cell, macrophage, eosinophil, TGF

Abbreviations: BB-DP – BioBreeding diabetes-prone; BCG – baccilus calmette-guerin; CD – Crohn’s disease; CDAI – Crohn’s disease activity index; CLR – C-type lectin receptors; CTLA-4 – cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4; DALY – disability adjusted life year; DC – dendritic cells; ES – excreted/secreted; FoxP3 – forkhead box P3; GF – germ-free; HIV – human immunodeficiency virus; IBD - inflammatory bowel disease; IFNγ – interferon gamma; Ig – immunoglobulin ; IL – interleukin; ILC2 – type 2 innate lymphoid cell; LNFPIII – lacto-N-fucopentaose III; LPS – lipopolysaccharide; MS – multiple sclerosis; NK – natual killer; NOD – non-obese diabetic; OdDHL – N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone; PRR – pathogen recognition receptor; SCA – S. mansoni cercariae antigen; SEA – S. mansoni egg antigen; STAT6 – signal transducer and activator of transcription 6; SWA – S. mansoni worm antigen; T1D – type 1 diabetes; T2D – type 2 diabetes; TGF-β – transforming growth factor beta; Th – T helper; TLR – toll-like receptor; TNF-α – tumor necrosis factor alpha; Treg – T regulatory; UC - ulcerative colitis; UCDAI – ulcerative colitis disease activity index

1. Introduction

The hygiene hypothesis, initially postulated to explain the rise of allergic conditions [1], has been extended to also provide an explanation for the rise of autoimmune diseases in industrialized countries. Increasing evidence suggests that reduced exposure to infectious diseases, as a result of improved hygiene and medical practice, is an important contributing factor in the rising incidence of autoimmune diseases. In Europe, the incidence of T1D increased at a rate of 3.9% per annum between 1989 and 2003 [2]. Other regions show similar increases. Although genetic loci have been identified that predispose individuals to T1D [3], the growth in the incidence of T1D in northern Europe and North America exceeds levels that can be explained by changes in the gene pool of the population. Furthermore, as T1D incidence continues to rise, the disease is increasingly occurring in patients with lower risk genotypes [4], suggesting that environmental factors may be fostering disease penetration even in relatively genetically protected populations.

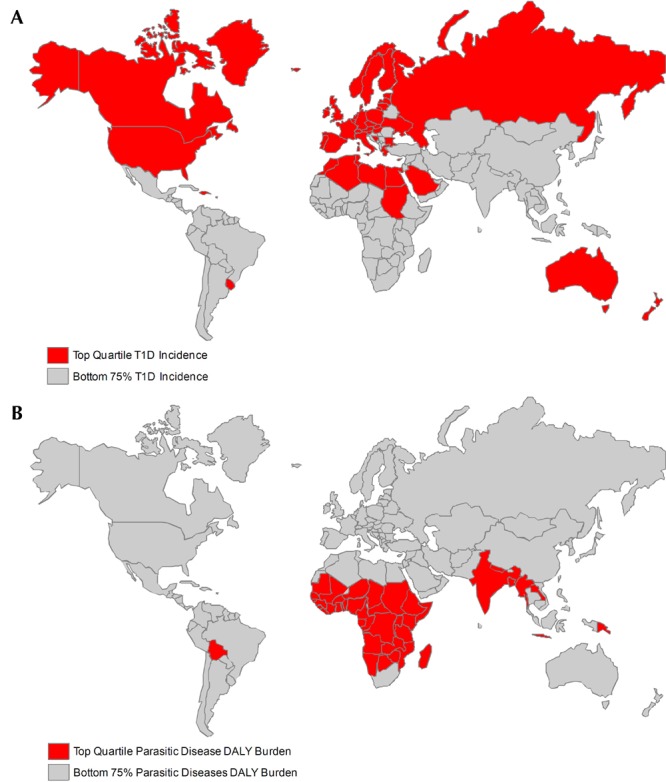

The inverse correlation between autoimmunity and infections can be observed when incidence and morbidity data are represented on global maps for infection and autoimmunity (Figure 1). These epidemiological data for the mirror image distribution of autoimmune versus infectious disease, together with studies in multiple animal models of autoimmune and inflammatory disease, lend support to the hygiene hypothesis. In truth, not all infections can prevent T1D; some have been associated with diabetes [5], including viral infections that have been suggested to be potential environmental triggers for diabetes in both human studies and in animal models of T1D [6]. However, with regard to helminth infections, studies in animal models strongly demonstrate that the immunomodulation induced by worm infection has beneficial effects on diabetes onset and progression [5]. Furthermore, increased T1D incidence in transmigratory populations, moving from a region of relatively low incidence to a region with higher incidence, suggests that environmental factors may play a role in the growing incidence of this autoimmune disease in the industrialized world [7]. Rigorous epidemiological human studies, looking at the prevalence of T1D in countries endemically infected with helminths, may contribute further confirmatory data.

Figure 1. Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes incidence and parasitic disease burden.

(A) Incidence of type 1 diabetes is increasing rapidly in the developed world. Nations with top quartile diabetes incidence among children age 0-14 are colored red, and nations with bottom 75% incidence are colored grey. Data are from the International Diabetes Federation [12]. (B) Global disease burden from parasitic diseases, including schistosomiasis, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, leishmaniasis, ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm, is clustered in the developing world. Nations in the top quartile of disability adjusted life year (DALY) burden from parasitic diseases are shown in red and nations in the bottom 75% of DALY burden are shown in grey. Data are from the World Health Organization [13].

One complication in charting and explaining the rise of T1D is that type 2 diabetes (T2D) and the metabolic syndrome are also increasing rapidly in developed and developing countries alike, constituting a much larger proportion of overall diabetes cases. While traditionally associated with T2D, the recognition of the role of insulin resistance in the onset and progression of T1D has blurred the borderlines between these two diseases, traditionally considered to be distinct [4, 8, 9]. Changes in lifestyle, including diet and physical activity, are clearly implicated in the global T2D epidemic, but it is unclear what role these factors play in the growing burden of T1D.

Among numerous other pathogens, helminths can establish themselves in a mammalian host on a chronic basis without succumbing to immune-mediated expulsion. They have developed strategies to instruct the host immune system to "tolerate" them. The initial host immune response to eradicate the parasite is gradually subverted, triggering the secretion of anti-inflammatory molecules and the development of regulatory cell populations. In some cases, the immune responses induced by helminths have been found to ameliorate or alleviate chronic inflammatory disorders. For example, a prospective study of multiple sclerosis (MS) patients harboring natural helminth infection (multiple species) demonstrated improved clinical outcomes in infected versus uninfected control patients [10].

Interest in the development of "drugs from bugs" for the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases is under active investigation at different levels, including the identification of pathogen-derived molecules that could prove useful as therapeutic agents [11]. Scientific panels and conferences devoted to research in this area have become increasingly common (for example, https://www.keystonesymposia.org/index.cfm?e=Web.Meeting.Program&Meetingid=1095).

In this review, we will discuss the implications of co-evolution between helminths and the human immune system in the context of increasing incidence of T1D and metabolic disease and how our immune equilibrium has been disrupted. We will also review the regulatory mechanisms induced by helminths that might have the potential to control T1D and inflammation more broadly.

2. Ancient "frenemies"

Infection with helminth parasites has been a persistent reality throughout our entire evolutionary history. We were exposed to these parasitic organisms long before we were human. Evidence of infections with mycobacteria and metazoan parasites extends deep into our prehistory, and analyses of prehistoric mummies and coprolites from diffuse geographies provide confirmation that humans have borne such infections extending back tens of thousands of years [14, 15]. We are not alone, as virtually without exception, all of our mammalian kinship is subject to similar parasitism by helminths, which exhibit extraordinary host specificity and restriction. Consistent with the age of this relationship, there is strong evidence that our parasitic passengers have evolved extensive adaptations to life inside the mammalian and, specifically, the human host, and that we, too, have evolved against the backdrop of exposure to helminths and other parasites.

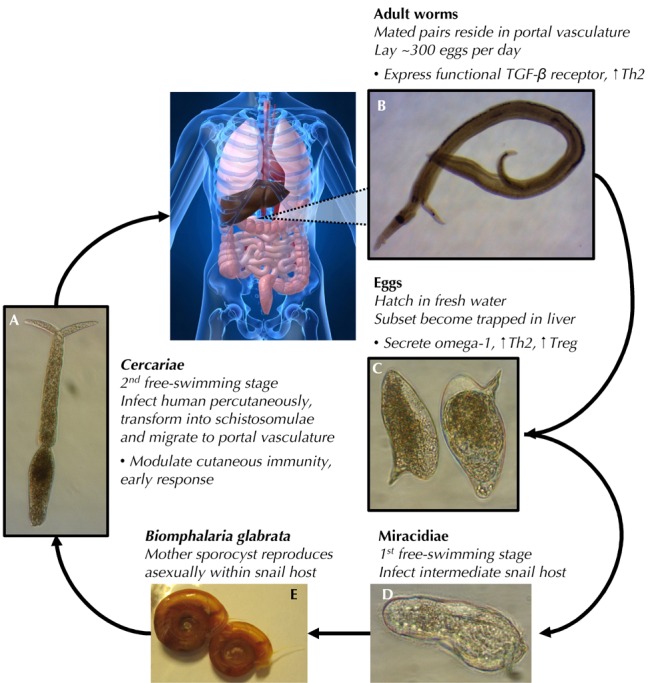

One illustration of this intricate co-evolution can be found in the life cycle of the human blood fluke, Schistosoma mansoni, which is the focus of much of our own work directed at investigation of the hygiene hypothesis in the context of T1D. S. mansoni is a trematode worm of the genus Schistosoma that pursues a complex life cycle, involving an intermediate snail host of the genus Biomphalaria, and infects humans as the definitive mammalian host. S. mansoni causes a tremendous disease burden globally, with an estimated 200 million people suffering from chronic infection, primarily in the developing world [16].

The life cycle of S. mansoni begins (see Figure 2) with the hatching of eggs upon exposure to fresh water, releasing miracidia, which then infect the intermediate molluscan host and undergo asexual reproduction to produce cercariae, the free swimming larval stage that infects man. Upon contact with human skin, cercariae adhere and invade the host, ultimately migrating to the portal vasculature, where mature worms form monogamously mated pairs and begin to lay ~300 eggs per day. Many of these eggs transit through the blood vessel and intestinal walls to reach the lumen of the intestine, from where they pass to the exterior and hatch into a new generation of miracidia. A proportion of eggs, however, are swept with the blood stream to the liver, where they cause granulomatous inflammation that, in the chronic setting, leads to the fibrosis and portal hypertension that underlie the pathological features of schistosomiasis.

Figure 2. Schistosoma mansoni life cycle.

(A) Sexually differentiated cercariae, swimming in fresh water, infect the human host, penetrating the skin. During host entry, cercariae lose their tails and mature into schistosomulae, then migrate to the portal vasculature where mature adult worms form mated pairs (B) and begin depositing eggs (C). Eggs are shed via the feces and, upon contact with fresh water, hatch into miracidia (D). Miracidia infect snails of the genus Biomphalaria (E), where they undergo asexual reproduction (mother sporocysts), producing the next generation of cercariae, which are shed again into fresh water. Life cycle stages, contacting the human host (A-C), are outlined in black. Bullet points outline selected immunomodulatory actions of cercariae/schistosomulae, adult worms, and eggs.

Driven by the selective pressure to successfully survive and reproduce within the blood vessels of its definitive host, S. mansoni has evolved into a master manipulator of the human immune system, and can survive in the vasculature without immune-mediated expulsion for up to 40 years [16-20]. This adaptation to the mammalian immune environment is so complete that S. mansoni actually depends upon components of the host immune system to complete its life cycle. Whereas, S. mansoni can form mated pairs and lay large numbers of eggs that successfully transit the intestine and reach the exterior in immunocompetent mice, maturation, egg laying, extravasation, and hepatic granuloma formation all were markedly impaired in the absence of functional B and T cells [21, 22].

The ability of schistosome worms to mature and reproduce in immunodeficient mice was restored by administration of exogenous TNF-α or reconstitution with CD4+ T cells, providing evidence that S. mansoni senses and depends upon host-derived immune factors for its maturation and reproduction. These findings are mirrored in the human clinical setting, where studies of HIV-positive patients in regions endemic for S. mansoni revealed that fecal egg counts, but not infection intensity, were negatively correlated with CD4+ T cell counts [23]. Further supporting the co-evolution of S. mansoni with the mammalian immune system, evidence exists that adult worms can sense the human regulatory cytokine, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), and that stimulation with TGF-β induces expression of genes linked to sexual maturation and male-female interaction and may modulate embryonic development [24-27]. S. mansoni has thus evolved not only to detect mediators of host immunity, but also to use these signals in its own program of maturation and reproduction.

These adaptations of S. mansoni are by no means an isolated occurrence in the world of helminths. Evidence supports similar adaptations and immunomodulatory capabilities across many other parasitic species, and certain features of helminth immunomodulation, especially the induction of a T helper 2 (Th2) and regulatory immune response (discussed in detail below), are largely conserved [19, 20].

Similarly to schistosomes, filarial nematodes establish chronic helminth infections that can persist for many years. They have developed a variety of strategies to evade and modulate the host's immune system [28]. Parasite transmission is mediated by blood-feeding arthropods. The life cycle is mainly completed in the mammalian host, where larvae and adult worms circulate, feed, and reproduce, exploiting both the lymphatic and the hematic host systems. Like schistosomes, these infections induce profound changes of the host immune system, including a tolerogenic signature in innate immune cells and the expansion of regulatory cell populations which are able to suppress Th1 and control Th2 immune responses [29, 30]. Filariasis cycle is mainly completed in the mammalian host, where larvae and adult worms circulate, feed, and reproduce, exploiting both the lymphatic and the hematic host systems. Like schistosomes, these infections induce profound changes of the host immune system, including a tolerogenic signature in innate immune cells and the expansion of regulatory cell populations which are able to suppress Th1 and control Th2 immune responses [29, 30]. Filariasis can be studied and modeled in laboratory animals, providing useful examples/evidence of co-evolution between helminth and mammalian host. Interesting observations on the significance of T regulatory (Treg) cells in helminth infections have been highlighted using a murine model of filariasis, Litomosoides sigmodontis [31]. In this model, Tregs are demonstrated to play a role in suppressing host immunity and in regulating fecundity of female parasites [32, 33].

Further well-studied examples of co-evolution between parasite and mammalian host immune system can be found in nematodes of the genus Trichinella, which have also been studied in models of T1D. Trichenella spiralis, which is among the best-studied parasites, invades the striated muscles of the host where it induces the formation of a collagen capsule (cyst). In contrast to S. mansoni, T. spiralis completes its life cycle in the host. Infection occurs by ingestion of raw meat containing encysted (live) T. spiralis larvae. The larvae are liberated from the cyst during digestion, and develop into adult worms in the small intestine where they mate. Eggs hatch inside the female uterus and new larvae migrate through blood vessels to the striated muscles, where new cysts are formed. During this process, products excreted/secreted (ES) by T. spiralis induce profound effects on the host immune system, deviating Th1 responses to Th2 by inducing dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages to acquire an immature, tolerogenic phenotype [34-37]. In addition to Th2 biasing, T. spiralis induces secretion of IL-10 and TGF-β by both innate and adaptive immune populations, contributing to regulation and containment of host tissue inflammation and fostering tissue repair [34, 38].

Heligmosomoides polygyrus is another helminth that, like S. mansoni and T. spiralis, has been investigated in the context of T1D. H. polygyrus is an intestinal nematode that naturally infects rodents as its definitive host and, as a result of its extensive adaptation to muroid immune systems, is among the best studied models of helminth infection in laboratory animals (both mice and rats). H. polygyrus larvae enter the duodenum from the oral route, penetrate the duodenal mucosa, and develop into adult worms that live, feed, mate, and lay eggs in the intestinal lumen. The eggs can either form granulomas in the intestinal mucosa or exit the intestine through the feces. Larvae, worms, and eggs all induce powerful responses in the gut mucosa, expanding, activating, and recruiting immune cells, in particular DCs and macrophages [39, 40]. Despite the fact that the H. polygyrus life cycle takes place in the intestine (without entering the circulation), the parasite potently modulates systemic immune responses. It has been investigated in many animal models of inflammatory disease, including T1D, colitis, allergy, asthma, and gastric atrophy [39, 41-48]. Type 2 immunity to H. polygyrus includes the expansion of Th2 and Treg populations. Studies have shown that H. polygyrus actively secretes proteins that induce expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 and a regulatory phenotype among CD4+ T cells via ligation of the host TGF-β receptor [49].

Consistent with these roles played by ES products in affecting the regulated Th2 immunity associated with T. spiralis, H. polygyrus, and S. mansoni, many other helminths have also been shown to selectively secrete products that modulate host immunity [50]. For example, ES-62, a leucine aminopeptidase secreted by another nematode parasite of rodents, Acanthocheilonema vitae, also has potent immunomodulatory properties, and has been reported to inhibit pro-inflammatory responses at least in part through interactions with TLR4 [11]. Among human pathogens, onchocystatin, a cysteine protease inhibitor secreted by the filarial nematode, Onchocerca vovlvulus, has been shown to induce a regulatory shift and suppress proliferation of human T cells [51, 52].

Despite longer generational times, there is little reason to believe that the mammalian and, specifically, the human immune system have remained static in this evolutionary arms race. It is more plausible that we have co-evolved with these old adversaries, driven by our opposing desire to expel or control them, and by the shared interest of parasite and host to limit tissue damage and pathology.

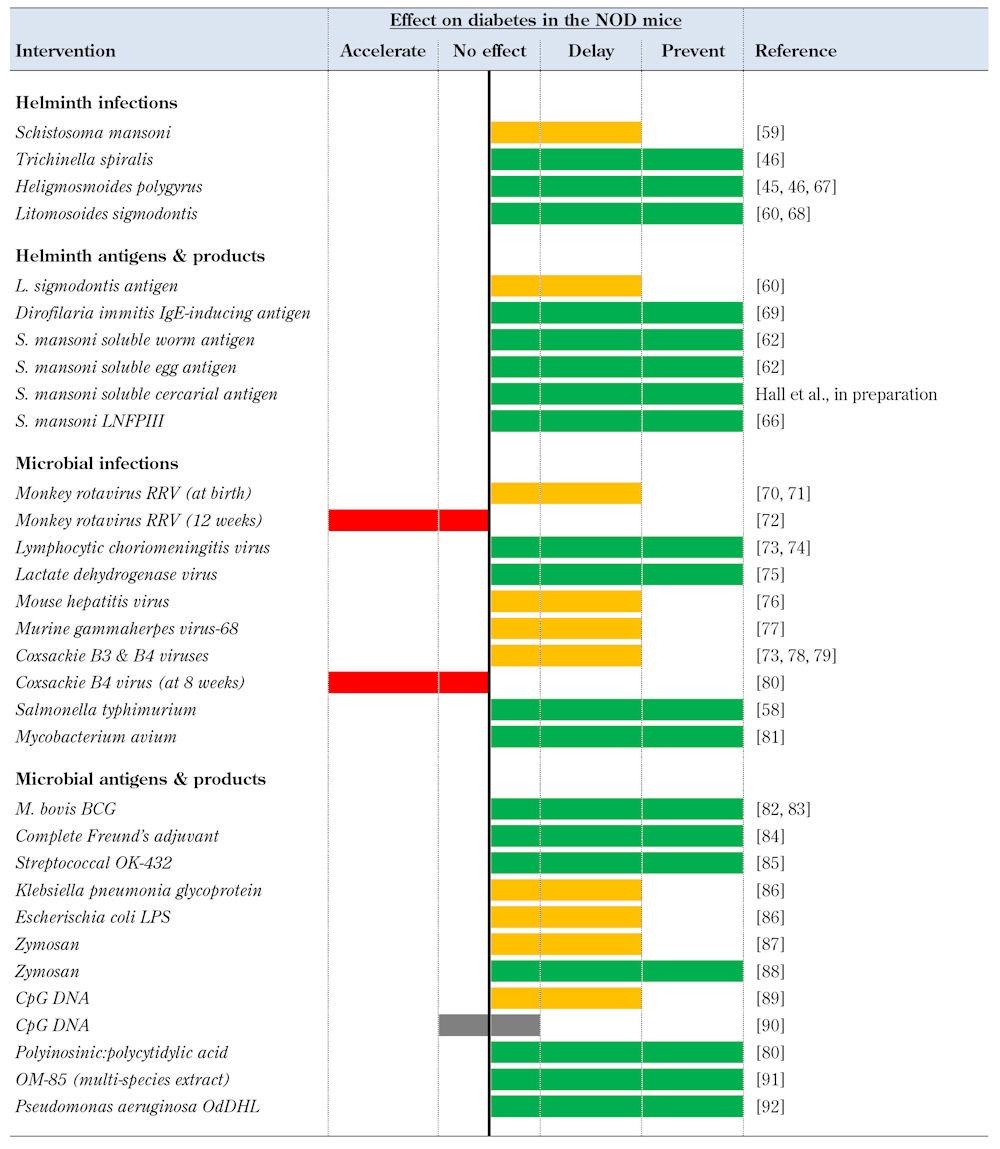

3. Prevention experiments in the non-obese diabetic mouse model of T1D

The non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse [53, 54] and the BioBreeding diabetes-prone (BB-DP) rat [55] constitute the most widely studied animal models of T1D. They have contributed significantly to our understanding of T1D as a clinical disease. In particular, the NOD mouse has been used extensively to investigate the interplay between infections and autoimmunity, and has generated significant data in support of the hygiene hypothesis in T1D (see Table 1 for a summary of selected studies).

Table 1. Selected pathogens and pathogen-derived products shown to modulate autoimmune diabetes in the NOD mouse.

Legend: LNFPIII – lacto-N-fucopentaose III, BCG – baccilus calmette-guerin, LPS – lipopolysaccharide, OdDHL – N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone.

The progression and pathology of autoimmune diabetes in the NOD mouse mirrors to a significant degree those of clinical T1D. Immune infiltration of the pancreas begins at approximately 5 weeks of age. The destruction of the pancreatic β-cells in NOD mice is caused by dysregulated mononuclear cells, and is generally described as Th1-mediated disease [56]. Antigen-presenting cells, including B cells, DCs, and macrophages, have been identified as key players in self-antigen presentation. Together with NK cells, these cells secrete inflammatory mediators that contribute to the recruitment of T lymphocytes (both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) that ultimately kill β-cells by apoptosis and necrosis.

The incidence of diabetes in NOD mice varies significantly between colonies. These differences seem to be linked to the conditions in which the animals are maintained, with degree of pathogen exposure inversely proportional to observed diabetes incidence [57]. For example, autoimmune susceptible animals kept under germ-free (GF) condition develop diabetes at high incidence. Conversely, animals housed in poor hygiene have a low incidence of diabetes, suggesting that infections (and also commensal bacteria) play crucial roles in the modulation of diabetes. These observations helped to kindle an interest among researchers to formally study the effect of infections on diabetes using the NOD mouse as a model for T1D (Table 1). Paradoxically, despite the Th1 character of the diabetogenic immune response in the NOD mouse, some Th1 infections and Th1-inducing microbial agents were found to prevent or delay diabetes in NOD mice. These include live infection with intracellular bacterial infections, such as Salmonella typhimurim [58], which prevented diabetes in the NOD mouse when administered from 8 weeks of age, and exposure to several viral pathogens (see Table 1).

Perhaps less surprising was the finding that Th2-skewing parasitic infections could ameliorate a Th1-mediated autoimmune disease like T1D. The first study to demonstrate the protective effect of helminth infections on diabetes was performed using S. mansoni infection in NOD mice, beginning at 5-6 weeks of age, which precedes intra-islet immune infiltration [59]. Infected mice exhibited reduced diabetes incidence and a marked Th2 immune response, manifesting features typical of murine models of schistosomiasis, including systemic eosinophilia. Subsequently, the influence of other live helminth infections were investigated in the NOD mouse (including T. spiralis, H. polygyrus, and L. sigmodontis; see Table 1), and all were found to prevent diabetes, strongly supporting the hypothesis that the immunomodulation induced by helminths has a broad capacity to suppress the onset and progression of T1D [45, 46, 60].

These encouraging findings in the context of live helminth infections led researchers to explore whether soluble antigens from multiple helminth species, in the absence of live infection, also were capable of modulating the initiation and course of autoimmune diabetes in the NOD mouse. In the case of S. mansoni, soluble antigen from both adult worm (SWA) and eggs (SEA) were shown to confer robust diabetes protection in the NOD mouse when administered from ~4-5 weeks of age. Evidence from adoptive transfer experiments suggest that the two antigens exert their effects via distinct mechanisms [61, 62].

Given that antigen preparations from helminths are able to recapitulate aspects of diabetes protection observed with live infections, the identification of specific helminth-derived products capable of immunomodulation and prevention of disease has become a major focus of research. In the case of S. mansoni, the glycoprotein omega-1 has been identified as a principal Th2-inducing factor in SEA and has been shown to expand Treg both in vitro and in vivo [63-65]. The S. mansoni-derived glycan, lacto-N-fucopentaose III (LNFPIII), has been reported to prevent diabetes in the NOD mouse [66], and numerous specific products from other helminths are under active investigation, for example ES-62 from A. viteae [11].

Together, animal studies of helminth infection and products in the NOD mouse provide strong evidence that we (mammals) might actually require the immunomodulatory effects of helminth antigens to maintain a balance in our immune system. In particular, these effects of helminth exposures may aid in the expansion of crucial regulatory cell populations (and the secretion of anti-inflammatory molecules) that are understimulated in the absence of our "old friends". Dissecting the immune response induced by helminths and their products may help to direct future therapeutic strategies.

4. Immunity to helminthes

As previously discussed, the co-evolution of mammals with a broad range of infectious agents has helped to shape the mammalian immune system, adapting cell functions and mechanisms of defence for each specific type of infection. Because of the size of helminth parasites, the host immune system must employ multiple players and develop different mechanisms to eradicate the uninvited guest.

Although the induced immune response varies between different helminth parasites, and is tailored to the site of "residence" within the host, immunity to helminths is referred to as Th2 or, more broadly, as type 2 immunity [93]. Th2 responses are fundamental to host survival in the face of helminth infection, and many different cell types play crucial roles in the secretion of cytokines able to amplify Th2-immunity. Besides the canonical Th2 cytokine, IL-4, the most studied cytokines involved in the immune response to helminths include IL-3, IL-5, IL-9, IL-10, IL-13, IL-25, and IL-33. These cytokines can be secreted during helminth infections not only by Th2-polarized CD4+ T cells, but also by antigen-presenting cells (B cells, DCs, and macrophages), granulocytes (eosinophils, mast cells, and basophils), or type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2). In addition to innate immune cells, epithelial cells also respond to the presence of helminths, and are an important source of type 2 cytokines (e.g. IL-25 and IL-33), often contributing to the activation and amplification of type 2 protective mechanisms early during the course of infection. Type 2 cytokines are fundamental in sustaining protective mechanisms against the parasite, including antibody production (IgG1, IgE, and IgG4 in humans) by B cells, smooth muscle contraction, mucus secretion by epithelial cells, and direct attack of the parasite with anti-helminth molecules secreted by granulocytes and epithelial cells [94].

Regulatory cells are also an important feature of immunity during helminth infections; these include both Foxp3-expressing CD4+ Treg cells and IL-10-secreting Tr1 cells [95]. Together with Th2 responses, both cell types are involved in the downmodulation of initial inflammatory and Th1 responses to the parasite. However, they can also regulate Th2 responses to maintain immune balance. In the absence of appropriate regulation, Th2 responses can cause destruction not only to the parasite, but also to host tissue, and cause pathology. The mechanisms by which Tregs restrain the activation and proliferation of other cells are mediated both by cell-cell interactions and by soluble factors [96]. Helminths induce the generation and expansion of Tregs, and enhance Treg function by inducing the expression of negative costimulatory molecules such as CTLA-4 and anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-10 and TGF-β.

After millions of years of co-evolution, it is often difficult to disentangle which aspects of the immune response induced by helminths favor the host and which favor the parasite. The resultant balance in Th2 and regulatory immune response, exhibited during chronic helminth infection, is possibly the best compromise between the two.

5. Mechanisms of helminth-mediated diabetes protection

The potent induction of Th2 and Treg responses associated with immunity to helminths provided the initial rationale for investigating the exposure to helminth infections or products to modulate the course of disease in animal models of T1D. As a Th1-mediated disease, it was hypothesized that skewing of the immune response along opposing Th2 and regulatory axes may act to regulate and suppress the diabetogenic Th1 response.

Most of the early papers, showing that helminth infection could prevent diabetes in NOD mice, focused on immune switch from Th1 to Th2 response, and suggested this as the primary mechanism of protection (see Table 1). Subsequent studies in NOD mice, utilizing live infections and helminth-derived products, began to focus attention on cells of the innate immune system, in particular on how helminth parasites and their antigens could trigger important phenotypic and functional changes in DC and macrophage populations [62, 97, 98]. This "anti-inflammatory" signature among cells of the innate immune system was shown to be responsible for induction of Th2 and Treg population expansion.

The interaction between pathogen recognition receptors (PRR) and helminth antigens has now been shown to be crucial for the induction of a tolerogenic phenotype among DC and alternative activation in macrophages. The study of how the complex mix of glycosylated proteins and lipids contained in crude helminth extracts interact at a molecular level with the different toll-like receptors (TLRs) and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) has been recognized as a key to understanding the mechanisms of immunomodulation by these products. This knowledge is essential for the design of immunomodulatory molecules and therapeutic protocols capable of inducing tolerance [99].

The presence of type 2 immune cells and regulatory cell types in the pancreas of NOD mice has been associated with the prevention of diabetes progression [61, 62, 100, 101]. Most studies demonstrated that the exposure to helminth infection and/or immunization has to take place before the bulk of the β-cell mass is compromised by autoimmune attack. Although interesting and encouraging, these findings suggest that helminth-derived therapies may be best suited to applications either in the prophylaxis of prediabetic patients or as tolerance-inducing co-therapies in the context of β-cell replacement approaches. More recently, work in the laboratory of Anne Cooke has demonstrated that larval antigens from S. mansoni cercariae (SCA), the infective life cycle stage that first contacts the mammalian host, can prevent diabetes in NOD mice (Table 1), not only from an early time point (4-5 weeks of age), but also much later in the progression of disease (10 weeks of age). SCA share some immunomodulatory effects with the well-studied S. mansoni extracts SEA and SWA, but appear to act via partially overlapping mechanisms. This provides evidence for novel roles of innate immune populations, both in the pancreas and systemically (Hall SW, et al., manuscript in preparation).

The mechanisms of diabetes protection induced by helminth infection are complex. They require multiple interactions between innate and adaptive immune cells. This complexity was demonstrated in studies using IL-4-deficient NOD mice that failed to develop a Th2 shift in response to H. polygyrus or L. sigmodontis, but still were protected from diabetes by the infection [67, 68]. On the other hand, the expansion of regulatory cell populations (Foxp3+-expressing and/or IL-10-secreting T cells) induced by helminth infections was shown to be dispensable for diabetes prevention in IL-4-competent NOD mice infected with H. polygyrus [45].

The initial model of Th2- and Treg-mediated control of pathogenic Th1 responses in the pancreas has evolved to reflect greater appreciation for the tolerogenic role of helminth infections. Exposure to helminth can induce tolerogenic and type 2 innate immune populations and thereby avert and suppress β-cell destruction. In the future, this cast of characters may expand to include not only immune populations local to the pancreas and pancreatic lymph nodes, but also other populations, including those in epithelial and adipose tissue, with the potential to modulate islet inflammation and stress.

6. Extending the hygiene hypothesis

Although the preponderance of work regarding the relevance of helminth infection and products to diabetes has focused on suppression or regulation of the autoimmune processes underlying T1D, emerging evidence suggests that the ancient relationship between mammals and helminth parasites may also have shaped aspects of metabolism more broadly.

Recent studies in the context of animal models of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes have highlighted the contributions of adipose-resident immune populations to the modulation of insulin responsiveness and glucose homeostasis. In particular, studies in mice fed a high fat diet have demonstrated that obesity is associated with a switch in the activation of adipose-resident macrophages towards an inflammatory, classically activated phenotype and away from the alternatively activated phenotype associated with lean, healthy adipose tissue [102]. These observations have been extended with the finding that the Th2-linked IL-4/STAT6 immune axis affects insulin sensitivity and peripheral nutrient metabolism, suggesting that immune pathways activated by exposure to helminths or their products might foster insulin responsiveness [103]. Further linking modulation of insulin sensitivity to cell populations associated with immunity to helminths, eosinophils and type 2 innate lymphoid cells have recently been identified as two adipose-resident immune populations with critical roles in maintaining the alternative activation of macrophages in metabolically active adipose tissue [104, 105]. Infection with the helminth, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, was shown to expand the number of both eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages resident in metabolically active adipose tissue, and to combat insulin resistance in mice fed a high fat diet [105].

These observations broaden the hygiene hypothesis, suggesting that helminth-derived therapies may have utility in the context of T2D and metabolic syndrome. Furthermore, with the growing appreciation of the role insulin resistance plays in the onset of T1D, exploration of these broader metabolic effects of helminths and their products may shed new light on the increasing incidence of T1D among lower risk genotypes.

7. Towards translation

Despite compelling data from animal models supporting the potential of helminth infection, or of therapies derived from helminth products, to modulate the course of T1D, clinical translation of these approaches has been slow and obstacles remain. In contrast to the defined timing parameters associated with autoimmune diabetes onset in the NOD mouse, human T1D patients present clinically with heterogeneous levels of residual β-cell function and disease progression. Despite this heterogeneity, by the time glycemic dysregulation is apparent, patients have generally lost an estimated ~70% of islet mass. These clinical realities have important implications for the translation of many of the helminth-derived interventions that have shown efficacy in the NOD mouse, as many of these studies have demonstrated the ability to prevent autoimmune diabetes before the establishment of insulitis, but not to halt or reverse disease at a later stage.

In the context of translational studies, the distinction between prophylaxis and therapy is paramount. Although animal data generated in the NOD mouse strongly support the potential of helminth infection or products to prevent disease, appropriate biomarkers do not currently exist to enable the identification and treatment of patients at sufficient risk of developing T1D early enough in disease progression. Without a means of targeting very high risk patients, prophylactic investigation of helminth-derived treatments would require very large studies of long duration, with extremely high development costs. Ethical and regulatory concerns are another barrier to prophylactic approaches, as any treatment used in this setting would need an extremely well-established safety profile to support a favorable risk-benefit assessment for administration to susceptible, but currently healthy, patients who may never develop T1D.

To date, clinical translation of helminth-derived therapies for the treatment of other autoimmune diseases, manifesting a relapsing-remitting profile, has proven more tractable and underscores the therapeutic potential of these approaches.

A prospective study of MS patients in Argentina, naturally infected with multiple species of helminth, revealed that these patients exhibited fewer exacerbations of disease, less variation in disability scores, and reduced radiological manifestations of MS than uninfected control patients during a 4.6 year study period [10]. Treatment of such naturally infected patients with anti-helminthic drugs induced a worsening of clinical measures of MS and an expansion of myelin-basic protein-specific peripheral blood mononuclear cells secreting the inflammatory cytokines IFNγ and IL-12, but a reduction in those cells secreting anti-inflammatory TGF-β and IL-10 [106]. These observations from naturally infected patients supported the investigation of therapeutic helminth infection of relapsing-remitting MS patients in a recently completed clinical study. Biweekly oral administration of 2,500 ova of the porcine whipworm, Trichuris suis, to a small cohort of MS patients over a 3-month treatment period reduced new gadolinium-enhancing lesions detected by magnetic resonance imaging relative to baseline, and induced an increase in regulatory IL-10 detected in serum; these effects returned to baseline within 2 months of cessation of T. suis ova therapy [107]. Although these data are from small, exploratory clinical studies, they are supportive of the potential of helminth-derived therapies in MS, and have paved the way for larger, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials.

Therapeutic administration of T. suis ova has also been investigated in the context of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), where multiple clinical trials support its potential to modify disease. An initial pilot study of T. suis ova in 7 patients with active Crohn's disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC) demonstrated that both a single dose of 2,500 ova and repeated dosing at 3 week intervals over the >28 week study period were well tolerated, with no significant adverse events [108]. Based on this favorable safety profile, T. suis ova was investigated in two larger efficacy studies in CD and UC. In an open label study enrolling 29 patients with active CD, oral administration of 2,500 T. suis ova at 3 week intervals for 24 weeks produced a 79.3% response rate (defined as a >100 point decline in Crohn's disease activity index (CDAI) or a decline to CDAI < 150) and a 72.4% remission rate (CDAI < 150) [109].

A second, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study investigated biweekly administration of 2,500 T. suis ova in 54 patients with active UC (defined as ulcerative colitis disease activity index (UCDAI) ≥ 4), and generated encouraging evidence of efficacy over the 12-week study period [110]. In this larger, controlled study, treatment with T. suis ova was well tolerated, with no significant adverse events, and generated a 43.3% response rate (defined as a decline of ≥4 points in UCDAI), versus a response rate of 16.7% in patients receiving placebo [110]. Together, these data strongly support the therapeutic potential of T. suis ova in IBD. Two larger randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trials are currently underway, enrolling a combined total of 470 patients with CD in the United States and Europe. In addition to T. suis ova, infection with the human hookworm, Necator americanus, also has been investigated clinically in the context of IBD, but these efforts are at an earlier stage [111].

8. Conclusions

Since the initial broadening of the hygiene hypothesis to encompass autoimmune diseases, the NOD mouse model of T1D has provided crucial data and insights regarding the interplay between infection and autoimmunity. Among the first demonstrations of this, experiments conducted in the NOD mouse showed that helminth infection is capable of altering the course of autoimmune diabetes and that helminth products and antigens, in the absence of live infection, can modulate the immune system in ways that suppress and control autoimmune destruction of islets and disease progression [59, 61, 62]. Furthermore, as a spontaneous model of autoimmunity, the NOD mouse has enabled detailed exploration of multiple mechanisms by which helminth infections and products exert their influences on underlying autoimmune processes.

Given this long history of basic insight derived from the NOD mouse, it is perhaps surprising that investigation of the hygiene hypothesis in other models of autoimmunity, including those of IBD and MS, have been more rapidly translated to the clinical setting. Whereas large, randomized and well-controlled trials of helminth therapy are underway on the heels of positive initial studies of T. suis in Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, and MS [107, 109, 110]. Similar investigation in T1D has lagged behind. However, these observations regarding the kinetics of clinical translation have held equally valid for other therapeutic approaches that have been investigated in multiple animal models of autoimmunity. For example, while TNFα blockade in rheumatoid arthritis and IBD [112], and α4β1 integrin blockade in MS [113], reached clinical practice relatively soon after initial investigations in relevant animal models, clinical translation of anti-CD3 therapy in T1D has proven to be a longer and more challenging path. However, the sluggish translation of findings from the NOD mouse to clinical practice does not necessarily constitute a comment on the clinical relevance of findings in this model so much as a testament to the unique challenges of developing novel therapies for T1D.

As discussed above, the distinction between prophylaxis and therapy is critical in the context of translational efforts for reasons related to clinical trial design, duration, and cost. Today, clinical T1D most frequently presents as an irreversible disease, where the majority of insulin-producing capacity has already been destroyed, and even complete, immediate arrest of further β-cell destruction would not enable a life free of exogenous insulin. Without the ability to intervene before β-cell destruction has progressed beyond a critical threshold, realizing the full potential of helminth-derived therapies in T1D remains an extreme challenge.

However, multiple lines of current research could enable the meaningful application of helminth-derived therapies for diabetes. First, efforts to develop novel biomarkers with better resolution and means of regenerating islet mass constitute major focuses of research. Either earlier intervention, or intervention in patients with restored islet mass, may fit well with the demonstrated ability of helminth-derived approaches to preserve islet mass and suppress β-cell destruction. Second, emerging evidence regarding the ability of helminth infection and helminth products to modulate adipose-resident immune populations in ways that foster improved insulin responsiveness suggest new applications for these approaches in the context of T2D and the metabolic syndrome.

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Wellcome Trust, Diabetes UK, JDRF, and MRC for the support they have provided for our research. The authors would also like to acknowledge all of our colleagues in the Cooke and Dunne research groups for helpful discussion and commentary.

References

- 1.Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ. 1989;299(6710):1259–1260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyurus E, Green A, Soltesz G. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989-2003 and predicted new cases 2005-20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet. 2009;373(9680):2027–2033. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60568-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polychronakos C, Li Q. Understanding type 1 diabetes through genetics: advances and prospects. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(11):781–792. doi: 10.1038/nrg3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fourlanos S, Varney MD, Tait BD, Morahan G, Honeyman MC, Colman PG, Harrison LC. The rising incidence of type 1 diabetes is accounted for by cases with lower-risk human leukocyte antigen genotypes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(8):1546–1549. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaccone P, Cooke A. Infectious triggers protect from autoimmunity. Semin Immunol. 2011;23(2):122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coppieters KT, Boettler T, von Herrath M. Virus infections in type 1 diabetes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(1):a007682. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodansky HJ, Staines A, Stephenson C, Haigh D, Cartwright R. Evidence for an environmental effect in the aetiology of insulin dependent diabetes in a transmigratory population. BMJ. 1992;304(6833):1020–1022. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6833.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fourlanos S, Narendran P, Byrnes GB, Colman PG, Harrison LC. Insulin resistance is a risk factor for progression to type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2004;47(10):1661–1667. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkin TJ. The accelerator hypothesis: weight gain as the missing link between Type I and Type II diabetes. Diabetologia. 2001;44(7):914–922. doi: 10.1007/s001250100548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correale J, Farez M. Association between parasite infection and immune responses in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2007;61(2):97–108. doi: 10.1002/ana.21067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harnett W, Harnett MM. Helminth-derived immunomodulators: can understanding the worm produce the pill? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(4):278–284. doi: 10.1038/nri2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 5 Edn. International Diabetes Federation; Brussels: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. WHO; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aspock H, Auer H, Picher O. Trichuris trichiura eggs in the neolithic glacier mummy from the Alps. Parasitology Today. 1996;12:255–256. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goncalves ML, Araujo A, Ferreira LF. Human intestinal parasites in the past: new findings and a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98(Suppl 1):103–118. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762003000900016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunne DW, Cooke A. A worm's eye view of the immune system: consequences for evolution of human autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(5):420–426. doi: 10.1038/nri1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chabasse D, Bertrand G, Leroux JP, Gauthey N, Hocquet P. Developmental bilharziasis caused by Schistosoma mansoni discovered 37 years after infestation. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1985;78(5):643–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearce EJ, MacDonald AS. The immunobiology of schistosomiasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(7):499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maizels RM, Pearce EJ, Artis D, Yazdanbakhsh M, Wynn TA. Regulation of pathogenesis and immunity in helminth infections. J Exp Med. 2009;206(10):2059–2066. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maizels RM, Yazdanbakhsh M. Immune regulation by helminth parasites: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(9):733–744. doi: 10.1038/nri1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amiri P, Locksley RM, Parslow TG, Sadick M, Rector E, Ritter D, McKerrow JH. Tumour necrosis factor alpha restores granulomas and induces parasite egg-laying in schistosome-infected SCID mice. Nature. 1992;356(6370):604–607. doi: 10.1038/356604a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies SJ, Grogan JL, Blank RB, Lim KC, Locksley RM, McKerrow JH. Modulation of blood fluke development in the liver by hepatic CD4+ lymphocytes. Science. 2001;294(5545):1358–1361. doi: 10.1126/science.1064462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karanja DM, Colley DG, Nahlen BL, Ouma JH, Secor WE. Studies on schistosomiasis in western Kenya: I. Evidence for immune-facilitated excretion of schistosome eggs from patients with Schistosoma mansoni and human immunodeficiency virus coinfections. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56(5):515–521. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beall MJ, Pearce EJ. Human transforming growth factor-beta activates a receptor serine/threonine kinase from the intravascular parasite Schistosoma mansoni. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(34):31613–31619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104685200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davies SJ, Shoemaker CB, Pearce EJ. A divergent member of the transforming growth factor beta receptor family from Schistosoma mansoni is expressed on the parasite surface membrane. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(18):11234–11240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freitas TC, Jung E, Pearce EJ. TGF-beta signaling controls embryo development in the parasitic flatworm Schistosoma mansoni. Plos Pathog. 2007;3(4):e52. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osman A, Niles EG, Verjovski-Almeida S, LoVerde PT. Schistosoma mansoni TGF-beta receptor II: role in host ligand-induced regulation of a schistosome target gene. Plos Pathog. 2006;2(6):e54. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yazdanbakhsh M. Common features of T cell reactivity in persistent helminth infections: lymphatic filariasis and schistosomiasis. Immunol Lett. 1999;65(1-2):109–115. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Babu S, Blauvelt CP, Kumaraswami V, Nutman TB. Regulatory networks induced by live parasites impair both Th1 and Th2 pathways in patent lymphatic filariasis: implications for parasite persistence. J Immunol. 2006;176(5):3248–3256. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoerauf A, Satoguina J, Saeftel M, Specht S. Immunomodulation by filarial nematodes. Parasite Immunol. 2005;27(10-11):417–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2005.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffmann W, Petit G, Schulz-Key H, Taylor D, Bain O, Le Goff L. Litomosoides sigmodontis in mice: reappraisal of an old model for filarial research. Parasitol Today. 2000;16(9):387–389. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(00)01738-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor MD, LeGoff L, Harris A, Malone E, Allen JE, Maizels RM. Removal of regulatory T cell activity reverses hyporesponsiveness and leads to filarial parasite clearance in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;174(8):4924–4933. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor MD, van der Werf N, Harris A, Graham AL, Bain O, Allen JE, Maizels RM. Early recruitment of natural CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg cells by infective larvae determines the outcome of filarial infection. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(1):192–206. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruschi F, Chiumiento L. Immunomodulation in trichinellosis: does Trichinella really escape the host immune system? Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2012;12(1):4–15. doi: 10.2174/187153012799279081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bian K, Zhong M, Harari Y, Lai M, Weisbrodt N, Murad F. Helminth regulation of host IL-4Ralpha/Stat6 signaling: mechanism underlying NOS-2 inhibition by Trichinella spiralis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(11):3936–3941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409461102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruschi F, Carulli G, Azzara A, Homan W, Minnucci S, Rizzuti-Gullaci A, Sbrana S, Angiolini C. Inhibitory effects of human neutrophil functions by the 45-kD glycoprotein derived from the parasitic nematode Trichinella spiralis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2000;122(1):58–65. doi: 10.1159/000024359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langelaar M, Aranzamendi C, Franssen F, Van Der Giessen J, Rutten V, van der Ley P, Pinelli E. Suppression of dendritic cell maturation by Trichinella spiralis excretory/secretory products. Parasite Immunol. 2009;31(10):641–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2009.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beiting DP, Gagliardo LF, Hesse M, Bliss SK, Meskill D, Appleton JA. Coordinated control of immunity to muscle stage Trichinella spiralis by IL-10, regulatory T cells, and TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2007;178(2):1039–1047. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hang L, Setiawan T, Blum AM, Urban J, Stoyanoff K, Arihiro S, Reinecker HC, Weinstock JV. Heligmosomoides polygyrus infection can inhibit colitis through direct interaction with innate immunity. J Immunol. 2010;185(6):3184–3189. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weng M, Huntley D, Huang IF, Foye-Jackson O, Wang L, Sarkissian A, Zhou Q, Walker WA, Cherayil BJ, Shi HN. Alternatively activated macrophages in intestinal helminth infection: effects on concurrent bacterial colitis. J Immunol. 2007;179(7):4721–4731. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bashir ME, Andersen P, Fuss IJ, Shi HN, Nagler-Anderson C. An enteric helminth infection protects against an allergic response to dietary antigen. J Immunol. 2002;169(6):3284–3292. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elliott DE, Setiawan T, Metwali A, Blum A, Urban JF Jr, Weinstock JV. Heligmosomoides polygyrus inhibits established colitis in IL-10-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34(10):2690–2698. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fox JG, Beck P, Dangler CA, Whary MT, Wang TC, Shi HN, Nagler-Anderson C. Concurrent enteric helminth infection modulates inflammation and gastric immune responses and reduces helicobacter-induced gastric atrophy. Nat Med. 2000;6(5):536–542. doi: 10.1038/75015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kitagaki K, Businga TR, Racila D, Elliott DE, Weinstock JV, Kline JN. Intestinal helminths protect in a murine model of asthma. J Immunol. 2006;177(3):1628–1635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Q, Sundar K, Mishra PK, Mousavi G, Liu Z, Gaydo A, Alem F, Lagunoff D, Bleich D, Gause WC. Helminth infection can reduce insulitis and type 1 diabetes through CD25- and IL-10-independent mechanisms. Infect Immun. 2009;77(12):5347–5358. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01170-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saunders KA, Raine T, Cooke A, Lawrence CE. Inhibition of autoimmune type 1 diabetes by gastrointestinal helminth infection. Infect Immun. 2007;75(1):397–407. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00664-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sutton TL, Zhao A, Madden KB, Elfrey JE, Tuft BA, Sullivan CA, Urban JF Jr, Shea-Donohue T. Anti-Inflammatory mechanisms of enteric Heligmosomoides polygyrus infection against trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis in a murine model. Infect Immun. 2008;76(10):4772–4782. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00744-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson MS, Taylor MD, Balic A, Finney CA, Lamb JR, Maizels RM. Suppression of allergic airway inflammation by helminth-induced regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202(9):1199–1212. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grainger JR, Smith KA, Hewitson JP, McSorley HJ, Harcus Y, Filbey KJ, Finney CA, Greenwood EJ, Knox DP, Wilson MS, Belkaid Y, Rudensky AY, Maizels RM. Helminth secretions induce de novo T cell Foxp3 expression and regulatory function through the TGF-beta pathway. J Exp Med. 2010;207(11):2331–2341. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hewitson JP, Grainger JR, Maizels RM. Helminth immunoregulation: the role of parasite secreted proteins in modulating host immunity. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;167(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lustigman S, Brotman B, Huima T, Prince AM, McKerrow JH. Molecular cloning and characterization of onchocystatin, a cysteine proteinase inhibitor of Onchocerca volvulus. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(24):17339–17346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schonemeyer A, Lucius R, Sonnenburg B, Brattig N, Sabat R, Schilling K, Bradley J, Hartmann S. Modulation of human T cell responses and macrophage functions by onchocystatin, a secreted protein of the filarial nematode Onchocerca volvulus. J Immunol. 2001;167(6):3207–3215. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kikutani H, Makino S. The murine autoimmune diabetes model: NOD and related strains. Adv Immunol. 1992;51:285–322. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60490-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Makino S, Kunimoto K, Muraoka Y, Mizushima Y, Katagiri K, Tochino Y. Breeding of a non-obese, diabetic strain of mice. Jikken Dobutsu. 1980;29(1):1–13. doi: 10.1538/expanim1978.29.1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yale JF, Marliss EB. Altered immunity and diabetes in the BB rat. Clin Exp Immunol. 1984;57(1):1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anderson MS, Bluestone JA. The NOD mouse: a model of immune dysregulation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:447–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ohsugi T, Kurosawa T. Increased incidence of diabetes mellitus in specific pathogen-eliminated offspring produced by embryo transfer in NOD mice with low incidence of the disease. Lab Anim Sci. 1994;44(4):386–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zaccone P, Raine T, Sidobre S, Kronenberg M, Mastroeni P, Cooke A. Salmonella typhimurium infection halts development of type 1 diabetes in NOD mice. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34(11):3246–3256. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cooke A, Tonks P, Jones FM, O'Shea H, Hutchings P, Fulford AJ, Dunne DW. Infection with Schistosoma mansoni prevents insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in non-obese diabetic mice. Parasite Immunol. 1999;21(4):169–176. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1999.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hubner MP, Stocker JT, Mitre E. Inhibition of type 1 diabetes in filaria-infected non-obese diabetic mice is associated with a T helper type 2 shift and induction of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Immunology. 2009;127(4):512–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02958.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zaccone P, Burton O, Miller N, Jones FM, Dunne DW, Cooke A. Schistosoma mansoni egg antigens induce Treg that participate in diabetes prevention in NOD mice. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(4):1098–1107. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zaccone P, Fehervari Z, Jones FM, Sidobre S, Kronenberg M, Dunne DW, Cooke A. Schistosoma mansoni antigens modulate the activity of the innate immune response and prevent onset of type 1 diabetes. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33(5):1439–1449. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Everts B, Perona-Wright G, Smits HH, Hokke CH, van der Ham AJ, Fitzsimmons CM, Doenhoff MJ, van der Bosch J, Mohrs K, Haas H, Mohrs M, Yazdanbakhsh M, Schramm G. Omega-1, a glycoprotein secreted by Schistosoma mansoni eggs, drives Th2 responses. J Exp Med. 2009;206(8):1673–1680. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steinfelder S, Andersen JF, Cannons JL, Feng CG, Joshi M, Dwyer D, Caspar P, Schwartzberg PL, Sher A, Jankovic D. The major component in schistosome eggs responsible for conditioning dendritic cells for Th2 polarization is a T2 ribonuclease (omega-1) J Exp Med. 2009;206(8):1681–1690. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zaccone P, Burton OT, Gibbs SE, Miller N, Jones FM, Schramm G, Haas H, Doenhoff MJ, Dunne DW, Cooke A. The S. mansoni glycoprotein omega-1 induces Foxp3 expression in NOD mouse CD4(+) T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41(9):2709–2718. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harn DA, McDonald J, Atochina O, Da'dara AA. Modulation of host immune responses by helminth glycans. Immunol Rev. 2009;230(1):247–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mishra PK, Patel N, Wu W, Bleich D, Gause WC. Prevention of type 1 diabetes through infection with an intestinal nematode parasite requires IL-10 in the absence of a Th2-type response. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6(2):297–308. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hubner MP, Shi Y, Torrero MN, Mueller E, Larson D, Soloviova K, Gondorf F, Hoerauf A, Killoran KE, Stocker JT, Davies SJ, Tarbell KV, Mitre E. Helminth protection against autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice is independent of a type 2 immune shift and requires TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2012;188(2):559–568. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Imai S, Tezuka H, Fujita K. A factor of inducing IgE from a filarial parasite prevents insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in nonobese diabetic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286(5):1051–1058. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Harrison LC. Vaccination against self to prevent autoimmune disease: the type 1 diabetes model. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86(2):139–145. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Graham KL, O'Donnell JA, Tan Y, Sanders N, Carrington EM, Allison J, Coulson BS. Rotavirus infection of infant and young adult nonobese diabetic mice involves extraintestinal spread and delays diabetes onset. J Virol. 2007;81(12):6446–6458. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00205-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Graham KL, Sanders N, Tan Y, Allison J, Kay TW, Coulson BS. Rotavirus infection accelerates type 1 diabetes in mice with established insulitis. J Virol. 2008;82(13):6139–6149. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00597-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Filippi CM, Estes EA, Oldham JE, von Herrath MG. Immunoregulatory mechanisms triggered by viral infections protect from type 1 diabetes in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(6):1515–1523. doi: 10.1172/JCI38503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oldstone MB. Viruses as therapeutic agents. I. Treatment of nonobese insulin-dependent diabetes mice with virus prevents insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus while maintaining general immune competence. J Exp Med. 1990;171(6):2077–2089. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.6.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Takei I, Asaba Y, Kasatani T, Maruyama T, Watanabe K, Yanagawa T, Saruta T, Ishii T. Suppression of development of diabetes in NOD mice by lactate dehydrogenase virus infection. J Autoimmun. 1992;5(6):665–673. doi: 10.1016/0896-8411(92)90184-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wilberz S, Partke HJ, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Herberg L. Persistent MHV (mouse hepatitis virus) infection reduces the incidence of diabetes mellitus in non-obese diabetic mice. Diabetologia. 1991;34(1):2–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00404016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith KA, Efstathiou S, Cooke A. Murine gammaherpesvirus-68 infection alters self-antigen presentation and type 1 diabetes onset in NOD mice. J Immunol. 2007;179(11):7325–7333. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Davydova B, Harkonen T, Kaialainen S, Hovi T, Vaarala O, Roivainen M. Coxsackievirus immunization delays onset of diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice. J Med Virol. 2003;69(4):510–520. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tracy S, Drescher KM, Chapman NM, Kim KS, Carson SD, Pirruccello S, Lane PH, Romero JR, Leser JS. Toward testing the hypothesis that group B coxsackieviruses (CVB) trigger insulin-dependent diabetes: inoculating nonobese diabetic mice with CVB markedly lowers diabetes incidence. J Virol. 2002;76(23):12097–12111. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.12097-12111.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Serreze DV, Hamaguchi K, Leiter EH. Immunostimulation circumvents diabetes in NOD/Lt mice. J Autoimmun. 1989;2(6):759–776. doi: 10.1016/0896-8411(89)90003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bras A, Aguas AP. Diabetes-prone NOD mice are resistant to Mycobacterium avium and the infection prevents autoimmune disease. Immunology. 1996;89(1):20–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-717.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Baxter AG, Healey D, Cooke A. Mycobacteria precipitate autoimmune rheumatic disease in NOD mice via an adjuvant-like activity. Scand J Immunol. 1994;39(6):602–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1994.tb03419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Harada M, Kishimoto Y, Makino S. Prevention of overt diabetes and insulitis in NOD mice by a single BCG vaccination. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1990;8(2):85–89. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(90)90017-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sadelain MW, Qin HY, Lauzon J, Singh B. Prevention of type I diabetes in NOD mice by adjuvant immunotherapy. Diabetes. 1990;39(5):583–589. doi: 10.2337/diab.39.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Toyota T, Satoh J, Oya K, Shintani S, Okano T. Streptococcal preparation (OK-432) inhibits development of type I diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 1986;35(4):496–499. doi: 10.2337/diab.35.4.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sai P, Rivereau AS. Prevention of diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse by oral immunological treatments. Comparative efficiency of human insulin and two bacterial antigens, lipopolysacharide from Escherichia coli and glycoprotein extract from Klebsiella pneumoniae. Diabetes Metab. 1996;22(5):341–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Burton OT, Zaccone P, Phillips JM, De La Pena H, Fehervari Z, Azuma M, Gibbs S, Stockinger B, Cooke A. Roles for TGF-beta and programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 in regulatory T cell expansion and diabetes suppression by zymosan in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2010;185(5):2754–2762. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Karumuthil-Melethil S, Perez N, Li R, Vasu C. Induction of innate immune response through TLR2 and dectin 1 prevents type 1 diabetes. J Immunol. 2008;181(12):8323–8334. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Quintana FJ, Rotem A, Carmi P, Cohen IR. Vaccination with empty plasmid DNA or CpG oligonucleotide inhibits diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice: modulation of spontaneous 60-kDa heat shock protein autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2000;165(11):6148–6155. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lee BJ, Kim SK, Kim MK, Park ES, Cho HC, Shim MS, Kim MJ, Shin YG, Chung CH. Limited effect of CpG ODN in preventing type 1 diabetes in NOD mice. Yonsei Med J. 2005;46(3):341–346. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2005.46.3.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Alyanakian MA, Grela F, Aumeunier A, Chiavaroli C, Gouarin C, Bardel E, Normier G, Chatenoud L, Thieblemont N, Bach JF. Transforming growth factor-beta and natural killer T-cells are involved in the protective effect of a bacterial extract on type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55(1):179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pritchard DI, Todd I, Brown A, Bycroft BW, Chhabra SR, Williams P, Wood P. Alleviation of insulitis and moderation of diabetes in NOD mice following treatment with a synthetic Pseudomonas aeruginosa signal molecule, N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone. Acta Diabetol. 2005;42(3):119–122. doi: 10.1007/s00592-005-0190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Maizels RM, Hewitson JP, Smith KA. Susceptibility and immunity to helminth parasites. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(4):459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Allen JE, Maizels RM. Diversity and dialogue in immunity to helminths. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;11(6):375–388. doi: 10.1038/nri2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Belkaid Y, Tarbell K. Regulatory T cells in the control of host-microorganism interactions (*) Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:551–589. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Taylor MD, van der Werf N, Maizels RM. T cells in helminth infection: the regulators and the regulated. Trends Immunol. 2012;33(4):181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.MacDonald AS, Straw AD, Dalton NM, Pearce EJ. Cutting edge: Th2 response induction by dendritic cells: a role for CD40. J Immunol. 2002;168(2):537–540. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zaccone P, Burton OT, Gibbs S, Miller N, Jones FM, Dunne DW, Cooke A. Immune modulation by Schistosoma mansoni antigens in NOD mice: effects on both innate and adaptive immune systems. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:795210. doi: 10.1155/2010/795210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.van Die I, Cummings RD. Glycan gimmickry by parasitic helminths: a strategy for modulating the host immune response? Glycobiology. 2010;20(1):2–12. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Parsa R, Andresen P, Gillett A, Mia S, Zhang XM, Mayans S, Holmberg D, Harris RA. Adoptive transfer of immunomodulatory M2 macrophages prevents type 1 diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2012;61(11):2881–2892. doi: 10.2337/db11-1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pennline KJ, Roque-Gaffney E, Monahan M. Recombinant human IL-10 prevents the onset of diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;71(2):169–175. doi: 10.1006/clin.1994.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(1):175–184. doi: 10.1172/JCI29881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Red Eagle A, Odegaard JI, Jouihan H, Morel CR, Heredia JE, Mukundan L, Wu D, Locksley RM, Chawla A. IL-4/STAT6 immune axis regulates peripheral nutrient metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(52):22617–22622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009152108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Molofsky AB, Nussbaum JC, Liang HE, Van Dyken SJ, Cheng LE, Mohapatra A, Chawla A, Locksley RM. Innate lymphoid type 2 cells sustain visceral adipose tissue eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages. J Exp Med. 2013 doi: 10.1084/jem.20121964. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wu D, Molofsky AB, Liang HE, Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Jouihan HA, Bando JK, Chawla A, Locksley RM. Eosinophils sustain adipose alternatively activated macrophages associated with glucose homeostasis. Science. 2011;332(6026):243–247. doi: 10.1126/science.1201475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Correale J, Farez MF. The impact of parasite infections on the course of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;233(1-2):6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fleming J, Isaak A, Lee J, Luzzio C, Carrithers M, Cook T, Field A, Boland J, Fabry Z. Probiotic helminth administration in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a phase 1 study. Mult Scler. 2011;17(6):743–754. doi: 10.1177/1352458511398054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Summers RW, Elliott DE, Qadir K, Urban JF Jr, Thompson R, Weinstock JV. Trichuris suis seems to be safe and possibly effective in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(9):2034–2041. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Summers RW, Elliott DE, Urban JF Jr, Thompson R, Weinstock JV. Trichuris suis therapy in Crohn's disease. Gut. 2005;54(1):87–90. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.041749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Summers RW, Elliott DE, Urban JF Jr, Thompson RA, Weinstock JV. Trichuris suis therapy for active ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(4):825–832. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Croese J, O'Neil J, Masson J, Cooke S, Melrose W, Pritchard D, Speare R. A proof of concept study establishing Necator americanus in Crohn's patients and reservoir donors. Gut. 2006;55(1):136–137. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.079129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Feldmann M, Maini RN. Anti-TNF therapy, from rationale to standard of care: what lessons has it taught us? J Immunol. 2010;185(2):791–794. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1090051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Steinman L. Blocking adhesion molecules as therapy for multiple sclerosis: natalizumab. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4(6):510–518. doi: 10.1038/nrd1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]