Abstract

Prior research suggests that stigma plays a role in racial/ethnic health disparities. However, there is limited understanding about the mechanisms by which stigma contributes to HIV-related disparities in risk, incidence and screening, treatment, and survival and what can be done to reduce the impact of stigma on these disparities. We introduce the Stigma and HIV Disparities Model to describe how societal stigma related to race and ethnicity is associated with racial/ethnic HIV disparities via its manifestations at the structural level (e.g., residential segregation) as well as the individual level among perceivers (e.g., discrimination) and targets (e.g., internalized stigma). We then review evidence of these associations. Because racial/ethnic minorities at risk of and living with HIV often possess multiple stigmas (e.g., HIV-positive, substance use), we adopt an intersectionality framework and conceptualize interdependence among co-occurring stigmas. We further propose a resilience agenda and suggest that intervening on modifiable strength-based moderators of the association between societal stigma and disparities can reduce disparities. Strengthening economic and community empowerment and trust at the structural level, creating common ingroup identities and promoting contact with people living with HIV among perceivers at the individual level, and enhancing social support and adaptive coping among targets at the individual level can improve resilience to societal stigma and ultimately reduce racial/ethnic HIV disparities.

Keywords: Stigma, Discrimination, Disparities, HIV/AIDS, Race/Ethnicity

Stigma and Racial/Ethnic HIV Disparities: Moving Toward Resilience

The National HIV/AIDS Strategy, coordinated by the White House Office of National AIDS Policy, notes that “HIV disproportionately affects the most vulnerable in our society—those Americans who have less access to prevention and treatment services” (p. ix) and that the reduction of stigma is a critical step toward decreasing HIV disparities and health inequities (The White House Office of National AIDS Policy, 2010). Moreover, accumulating research demonstrates that societal stigma associated with race and ethnicity contributes to general disparities in mental and physical health (Williams & Mohammed, 2009) and health care (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003). Yet, there is currently limited understanding of how stigma contributes to racial/ethnic HIV disparities and what can be done to reduce the impact of stigma to alleviate these disparities. To address these gaps, we propose and review support for the Stigma and HIV Disparities Model and propose a resilience agenda specifying strategies to reduce racial/ethnic HIV disparities resulting from societal stigma.

Stigma and HIV Disparities Model

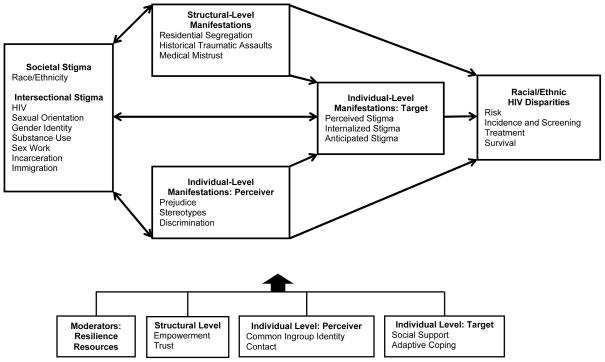

The Stigma and HIV Disparities Model in Figure 1 identifies fundamental processes in the relationship between societal stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities, including risk, incidence and screening, treatment, and survival. Societal stigma is social devaluation and discrediting associated with a personal attribute, mark, or characteristic such as race, ethnicity, or sexual minority orientation (Goffman, 1963). Societal stigma related to race/ethnicity ultimately contributes to and maintains racial/ethnic HIV disparities through its manifestations at the structural and individual levels. Furthermore, as depicted by bi-directional arrows within the model, societal stigma is sustained through the co-occurrence of its manifestations (Link & Phelan, 2001). That is, structural and individual-level stigma manifestations reinforce differences in status, resources, and social and political influence in ways that reinforce and justify societal stigma. Although the Stigma and HIV Disparities Model focuses on basic psychosocial processes, it recognizes that social context can critically shape the degree to which and how societal stigma is manifested.

Figure 1.

Stigma and HIV Disparities Model.

Stigma Manifestations

At the structural level, stigma manifestations include residential segregation, historical traumatic assaults, and medical mistrust. Residential segregation, an enduring legacy of institutional racism, is a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health (Williams & Collins, 2001). Similarly, a history of traumatic assaults including slavery, oppression, genocide, cultural destruction, displacement, and land loss, has left an enduring legacy on the health and psychological well-being of members of devalued groups, including Native Americans/Alaskan Natives (Walters, Beltran, Huh, & Evans-Campbell, 2011) and Blacks (Jones, Engelman, Turner, & Campbell, 2009). For example, historical traumatic assaults have disrupted traditional Native medicine services and customs (e.g., herbal and holistic alternative medicine) and led to historical trauma, a form of psychological injury experienced as depression, anxiety, anger, and avoidance (Whitbeck, Adams, Hoyt, & Chen, 2004). A history of unethical medical experimentation as well as contemporary discrimination within healthcare settings has resulted in mistrust of healthcare, medical providers, medical treatments, and the public health establishment among Black, Latino, and other communities (Corbie-Smith, Thomas, & St George, 2002). This mistrust can take on the form of “conspiracy beliefs” or beliefs about large-scale discrimination by the government (e.g., “The government is using AIDS as a way of killing off minority groups”; “HIV is a manmade virus”) (Bogart & Thornburn, 2005).

At the individual level, societal stigma associated with race and ethnicity is manifested as stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination among perceivers (Dovidio et al., 2008). Prejudice is a negative orientation toward stigmatized people, and can be experienced as an emotion such as anger, disgust, or fear. Stereotyping involves attributing specific characteristics, such as low intelligence or promiscuity, to group members. Discrimination is unfair behavior. Although explicit biases (i.e., blatant and intentional) have decreased in recent years in the United States, subtle forms (i.e., implicit and unconscious) persist (Dovidio & Gaertner, 2004).

The Stigma and HIV Disparities Model further illustrates how societal stigma, as well as its structural and individual manifestations among perceivers, is ultimately manifested at the individual level among targets (i.e., those who possess the devalued characteristic) as perceived, anticipated, and internalized stigma (Earnshaw & Chaudoir, 2009). Perceived stigma involves the assessment of experiencing prejudice, stereotypes, and/or discrimination from others in the past and anticipated stigma involves expectations of such bias in the future. Internalized stigma, also referred to as self-stigma, represents devaluing and discrediting oneself or one’s group based on one’s stigma. These experiences reflect ways that individuals respond to or actively cope with stigma, operate in concert to negatively affect health, and have considerable implications for health disparities (Major, Mendes, & Dovidio, 2012).

Multiple Stigmas: An Intersectionality Framework

Understanding the role of stigma in racial/ethnic HIV disparities requires recognition of the intersectionality of stigma: that is, interdependence among multiple co-occurring devalued social identities (Cole, 2009). Racial/ethnic minorities at risk of and living with HIV often possess other stigmas beyond their race/ethnicity, including HIV itself and related stigmas such as sexual minority orientation, transgender identity or expression, illicit drug use, sex work, incarceration, and immigration. Although the role of societal stigma associated with race/ethnicity can be studied independently, we propose that considering how multiple stigmas interact with each other provides a fuller understanding of the impact of societal stigma on racial/ethnic HIV disparities.

An intersectional framework elucidates several key insights for understanding how stigma contributes to racial/ethnic HIV disparities. First, people at risk of and living with HIV typically experience discrimination stemming from multiple facets of their identity beyond their race/ethnicity (Logie, James, Tharao, & Loutfy, 2011). Second, the different combinations of these stigmatized identities can produce distinctive responses and experiences (Purdie-Vaughns & Eibach, 2008). For example, because some intersectional identities are much more prototypical (e.g., HIV-positive gay White men), they may be the main target of social discrimination at the individual level more so than intersectional identities that are less prototypical (e.g., HIV-positive gay Native American men), which may be more socially “invisible.” A third insight is the dynamic nature of stigma and how the basis and nature of stigma can vary for the same person across contexts. For instance, Black men living with HIV who have sex with men may be stigmatized in White communities due to their race, in Black communities (e.g., faith-based organizations) due to their sexual orientation, and in Black and gay communities due to their sero-status (Bluthenthal et al., 2012).

Reviewing the Evidence

Stark racial/ethnic disparities exist along the HIV prevention and care continuum (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). We next review racial/ethnic disparities among Blacks, Latinos, Native Americans/Alaskan Natives, and Asian Americans at the four points of the HIV prevention and care continuum represented in the model and discuss how societal stigma relates to these disparities. Notably, research on Native Americans/Alaskan Natives and Asian Americans is more limited than on Blacks and Latinos.

Risk

Although racial/ethnic HIV disparities begin with risk, differences in sexual and injection drug use risk behaviors among races/ethnicities are often small. In nationally representative research (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002), similar percentages of Black (46%), Latino (46%), and White (48%) high-risk heterosexual women report having multiple sexual partners. Slightly lower percentages of Latino (64%) than Black (75%) and White (69%) high-risk heterosexual men report multiple sexual partners. In contrast, lower percentages of Black (64%) than Latino (71%) and White (74%) men who have sex with men report having multiple sexual partners and engaging in risky sexual behaviors (Harawa et al., 2004). Moreover, a national survey of injection drug users found that Latinos (38%) were more likely to share needles than were Whites (33%), whereas Blacks (20%) were less likely (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002).

At the structural level, Blacks and Latinos are more likely to live in risk environments due to residential segregation – spaces in which factors external to the individual increase chances of HIV transmission (Rhodes, Singer, Bourgois, Friedman, & Strathdee, 2005) – such as neighborhoods that contain a higher concentration of sexually transmitted infections including HIV (Krieger, Waterman, Chen, Soobader, & Subramanian, 2003). People living in risk environments are not only more likely to acquire HIV, they are more likely to acquire other sexually transmitted infections, which further increases their vulnerability to HIV infection (Kalichman, Pellowski, & Turner, 2011). Risk environments also include the criminal justice system, in which Blacks are disproportionately represented and rates of HIV, sexual risk, and syringe sharing among injection drug users are higher than other environments (Okie, 2007; Rhodes et al., 2005). Multiple external risk factors often co-occur in risk environments, further enhancing chances of HIV transmission.

Also operating at the structural level, medical mistrust increases risk for HIV. Among Black men, research has linked HIV conspiracy beliefs with negative attitudes towards condoms, which in turn are associated with lower likelihood of using condoms consistently (Bogart & Thorburn, 2005). Conspiracy beliefs may relate to mistrust of information from public health officials regarding HIV, including how to reduce risk of transmission. Furthermore, historical trauma is associated with risk behaviors such as substance abuse and alcohol consumption among Native Americans/Alaskan Natives (Sotero, 2006; Walters et al., 2011). Substance use can directly elevate HIV risk through injection needle-sharing and indirectly elevate HIV risk by increasing the likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex.

Stigma manifested at the individual level among targets is associated with increased HIV sexual risk behavior. For example, Latino gay men who perceive stigma associated with their ethnicity and sexual orientation are more likely have unprotected sex with casual partners (Diaz, Ayala, & Bein, 2004). Latino gay men may cope with psychological distress resulting from perceived stigma associated with these intersecting stigmas by participating in sexual situations that increase their risk of having unprotected sex (e.g., sex under the influence of drugs). Additionally, internalized stigma is associated with sexual risk among gay and bisexual men (Valdiserri, 2002). People who feel internalized stigma may be more likely to participate in risky sexual situations as a temporary escape from shame and depression or because they seek self-validation through sexual encounters.

Stigma manifested at the individual level among targets is further associated with greater engagement in substance use. Gibbons and colleagues (2010) found that perceived stigma based on race is associated with increased substance use among Black adolescents and their parents. Gibbons and colleagues theorized that Blacks engage in substance use in part to cope with stress associated with perceived stigma, and that interactions characterized by stigma deplete self-regulatory functioning, which ultimately leads to less self-control to resist drug use. Additionally, internalized stigma associated with race is related to greater alcohol consumption among urban Black women (Taylor & Jackson, 1990).

Incidence and Screening

Juxtaposed with disparities in HIV risk, disparities in HIV incidence are striking. According to U.S. surveillance data (National Center for HIV/AIDS, 2010), although Blacks comprised about 12% of the population in states with confidential names-based reporting, they accounted for 45% of all new diagnoses in 2007–2010; Latinos comprised about 16% of the population but 22% of new diagnoses. In contrast, although Whites accounted for a greater percentage of new diagnoses (29%) than did Latinos, they made up 65% of the population. Moreover, Black men who have sex with men bear the greatest burden of all races/ethnicities and transmission groups (i.e., injection drug use, injection drug use plus men who have sex with men, heterosexual, and “other”) accounting for 40% of diagnoses among men who have sex with men among all races/ethnicities (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). At the intersection of age, race, and sexual orientation, the rate of increase in new infections from 2006–2009 – 48% – was greater among young Black men who have sex with men than any other racial/ethnic group (Prejean et al., 2011).

Racial/ethnic disparities also exist in HIV screening. Although Blacks (77%) and Latinos (58%) are more likely to report having ever been tested than are Whites (49%) (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2011), Blacks, Latinos, and Asians/Pacific Islanders test at a later stage in the HIV disease continuum (Chen, Gallant, & Page, 2012). The percentage of Blacks (16%) and Latinos (16%) who tested for HIV within 6 months of being infected is lower than for Whites (29%) (Schwarcz et al., 2007). The intersection of race/ethnicity with immigration status may widen disparities related to late testing (i.e., receipt of an AIDS diagnosis within a year after testing). In a study of 45 US border communities, people who were foreign-born were most likely to be late testers (Espinoza, Hall, & Hu, 2009).

Residential segregation at the structural level may play a role in racial/ethnic differences in HIV screening: Blacks and Latinos are more likely to reside in higher HIV prevalence regions, which are targeted for receiving more federal HIV prevention funds for testing. Moreover, HIV stigma manifested at the individual level among targets continues to be considered a major barrier to HIV screening (Obermeyer & Osborn, 2007). A positive diagnosis forever marks an individual with the stigma of HIV. People who anticipate that others will discriminate against them if they test positive for HIV may avoid testing. Also, people may not test due to anticipated stigma associated with risk behaviors or related stigmas. For example, men who have sex with men, people who engage in sex work, and people who inject drugs may delay testing or not test due to fear that others will suspect that they engage in a stigmatized behavior. Relatedly, Latinos who are undocumented may delay testing to conceal their residency status.

Treatment

Next in the HIV continuum, racial/ethnic disparities exist in medical treatment received by people living with HIV. Latinos have the longest delays between HIV diagnosis and engagement in care followed by Blacks, with Whites having the smallest delays (Turner et al., 2000). Latinos and Blacks have lower rates of engagement in HIV care than Whites (Shapiro et al., 1999). Blacks are least likely to receive antiretroviral treatment followed by Latinos, with Whites being most likely (Lillie-Blanton et al., 2010). Blacks are less adherent to antiretroviral treatment than are Whites (Johnson et al., 2003). The extent to which this disparity exists for Latinos is unclear; some studies have found that Latinos exhibit better adherence than other races/ethnicities (Silverberg, Leyden, Quesenberry, & Horberg, 2009), whereas others have shown that Latinos exhibit worse adherence than Whites (Oh et al., 2009).

At the structural level, residential segregation can affect availability and quality of care. Blacks are more likely to live in areas characterized by limited availability of health care (e.g., fewer physicians and institutions) and poorer health care quality (White, Haas, & Williams, 2012). Furthermore, language represents a barrier among people living with HIV who do not speak English, reducing the likelihood that they will seek medical care and increasing the probability of medication errors when they do (Murphy, Roberts, Hoffman, Molina, & Lu, 2003). Historical traumatic assaults have disrupted the availability of traditional Native medicine services and customs (Walters et al., 2011), which may be preferred by some Native Americans/Alaskan Natives living with HIV (Duran & Walters, 2004). Medical mistrust further exacerbates racial disparities in HIV care and treatment, possibly leading to a lower likelihood of accessing healthcare (Smedley et al., 2003). Medical mistrust may also lead to reluctance to adhere to provider recommendations. For example, Black men living with HIV who endorse treatment-related conspiracy beliefs, such as the belief that people who take antiretroviral treatments are “guinea pigs,” show lower adherence to antiretroviral treatment (Bogart, Wagner, Galvan, & Banks, 2010).

Stigma manifested at the individual level among perceivers plays a critical role in racial/ethnic disparities in treatment of HIV. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that physicians who hold implicit (i.e., unconscious) prejudice towards Black patients also have more negative stereotypes of and discriminate towards Black patients by providing them with poorer care (for a review, see Dovidio et al., 2008). Within HIV care and treatment specifically, stigma may affect provider prescription of antiretroviral therapy. King and colleagues (2004) found that White providers prescribed antiretroviral therapy to Black patients much later than to White patients. However, there were no differences in length of time before prescription between Black providers with Black patients and White providers with White patients. Differences in prescription of antiretroviral therapy are partly driven by provider stereotypes that Black patients will be less adherent (Stone, 2005). Many providers also believe that people living with HIV who currently or have in the past abused alcohol or injection drugs, homeless persons, and mothers of young children will have poor adherence, potentially influencing prescription.

Stigma manifested at the individual level among targets further undermines care and treatment. When receiving HIV care, people living with HIV perceive explicit stigma based on their race and socioeconomic status (Bird, Bogart, & Delahanty, 2004) as well as their HIV status (Schuster et al., 2005). Additionally, Black patients report receiving poorer care from and having less confidence in providers who are higher in implicit prejudice (Cooper et al., 2012). Perceived stigma from providers is associated with lower access to care (Kinsler, Wong, Sayles, Davis, & Cunningham, 2007) and greater likelihood of missing doctors’ appointments (Bird et al., 2004). People living with HIV who perceive stigma from health care providers may avoid health care contexts because they anticipate stigma from providers. People living with HIV who perceive stigma from others in general are also more likely to miss clinic appointments for HIV care (Vanable, Carey, Blair, & Littlewood, 2006). Not accessing care could help individuals conceal their HIV status. Additionally, internalized stigma is associated with decreased access to care (Sayles, Wong, Kinsler, Martins, & Cunningham, 2009). People with high internalized stigma may avoid treatment because they feel that they do not deserve care, or because they feel ashamed to discuss their HIV infection or related risk behaviors.

Stigma manifested at the individual level among targets can impair treatment adherence. A study at the intersection of race, HIV, and sexual orientation suggests that perceived stigma due to race plays a significant role in antiretroviral adherence: In a multivariate model including the effects of perceived stigma due to race, HIV, and sexual orientation, only perceived stigma due to race was a significant predictor of adherence (Bogart, Wagner, Galvan, & Klein, 2010). People living with HIV who have internalized stigma are also more likely to report suboptimal adherence (Sayles et al., 2009). They may decide not to take medication to avoid thinking about their HIV status.

Survival

Finally, racial and ethnic disparities exist at the end of the HIV continuum – in survival rates of people living with HIV (Simard, Fransua, Naishadham, & Jemal, 2012). Blacks and Native Americans/Alaskan Natives diagnosed with HIV show much higher death rates than Latinos, Whites, and Asians/Pacific Islanders, and are less likely to remain alive nine years post-diagnosis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008, 2011). In a simulation analysis, Latinos diagnosed with HIV were estimated to lose more life years from late antiretroviral treatment initiation and discontinuation compared to all other races/ethnicities, and Black women were estimated to lose more years of life due to late initiation and discontinuation than White women (Losina et al., 2009). However, this trend was reversed for Black versus White men, highlighting the importance of the intersection of race and gender.

Stigma manifested at the structural level may affect the survival of people living with HIV. The concentration of poverty in residentially segregated environments can lead to exposure to elevated levels of chronic and acute stressors at the individual, household, and neighborhood levels, including economic hardship and criminal victimization. Large racial/ethnic differences exist in exposure to multiple types of acute and chronic stressors, which contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health (Sternthal, Slopen, & Williams, 2011). Similarly, historical trauma has been conceptualized as a chronic stressor that can have negative health effects for Native Americans/Alaskan Natives (Sotero, 2006). Chronic stress is associated with faster HIV disease progression and shortened survival among people living with HIV (Leserman, 2003).

Perceived stigma and anticipated stigma at the individual level among targets further act as chronic stressors that can have harmful physiological (e.g., cardiovascular reactivity), psychological (e.g., anger, felt stress, anxiety), and behavioral (e.g., smoking) responses (Major et al., 2012). People living with HIV who perceive stigma report greater physical health and mental health symptoms (e.g., HIV symptoms, depressive symptoms) (Vanable et al., 2006), and those who internalize stigma report greater depression, anxiety, and hopelessness (Lee, Kochman, & Sikkema, 2002).

Setting a Resilience Agenda

Our review suggests that racial/ethnic HIV disparities exist but are not monolithic: Disparities do not affect different groups in a uniform way at each stage of the continuum. These variations imply the existence of factors that moderate the relationship between societal stigma and HIV disparities. Within this section we focus on resilience resources, which represent a suite of modifiable strength-based moderators that may be appropriate targets for intervention to address societal stigma and are depicted in the Stigma and HIV Disparities Model. Resilience can be defined as individuals’ capacity, combined with families’ and communities’ resources, to overcome serious threats to development and health (Ungar, 2008).

Given its impact on HIV disparities, eliminating societal stigma associated with race/ethnicity, HIV, and related stigmas would likely significantly reduce HIV disparities. Our Stigma and HIV Disparities Model suggests that reductions in the manifestations of stigma will reduce societal stigma because of the feedback loops that exist between them. It is critical to adopt initiatives to reduce stigma manifestations generally (see, for example, Paluck, 2009) and within healthcare contexts specifically (Smedley et al., 2003) to eliminate societal stigma. However, because societal stigma has proven difficult to eliminate or diminish significantly, we suggest enhancing resilience to societal stigma at the structural and individual levels as a critical strategy to reduce HIV disparities.

Structural Level

At the structural level, the community psychology, sociology, and public health literatures suggest innovative interventions to reduce the impact of societal stigma on HIV disparities. Interventions that empower and build trust among devalued communities can disrupt the deleterious effects of residential segregation, historical traumatic assaults, and medical mistrust on health outcomes relevant to HIV disparities.

Empowerment

Empowerment can be fostered at the individual and community level through economic policy change and community education and mobilization. Among individuals, economic empowerment and racial/ethnic pride may reduce HIV risk behavior. At-risk women who were taught to market and sell jewelry experienced increases in income, and reductions in receiving drugs or money for sex, number of sex trade partners, and money spent on drugs (Sherman, German, Cheng, Marks, & Bailey-Kloche, 2006). Empowerment in the form of racial/ethnic pride may be accomplished through racial socialization, in which parents and other adults transmit messages to children about racial/ethnic heritage and prepare youth for future racism-related challenges (Hughes, 2003). For example, research can evaluate the effectiveness of neighborhood and school events in educating children about cultural holidays as well as historical and current political figures of their own race/ethnicity, and parents in teaching youth how to recognize and cope with mistreatment due to race.

At the structural level, communities can be empowered for change via increased community capacity, defined as resources to address community problems, as well as the development and deployment of skills, knowledge, and resources that can aid in this effort (Goodman et al., 1998). Various community institutions (e.g., families, neighborhoods, schools, churches, businesses, and volunteer agencies), which often have unrealized or unrecognized capacity, can be enlisted as agents of change for effective solutions to local problems (McLeroy, Norton, Kegler, Burdine, & Sumaya, 2003). Community-based interventions can go beyond merely using the community as the setting of the intervention, to viewing the community as a vehicle of change via community policies, environments, institutions and services (McLeroy et al., 2003). Community-based interventions that provide resources to improve neighborhood conditions may be particularly effective in reducing health disparities, given that improved neighborhood conditions are associated with lower levels of substance abuse, fewer health problems, and greater satisfaction with medical care (Fauth, Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2004). Furthermore, empowerment can be fostered in Native American/Alaskan Native communities by strengthening traditional Native medicine services and customs that have been weakened by historical traumatic assaults. Ultimately, traditional Native medicine services may be integrated with HIV treatment services to provide culturally appropriate care for Native Americans/Alaskan Natives living with HIV (Duran & Walters, 2004).

Trust

To overcome medical mistrust, social and health services can be positioned in communities rather than healthcare institutions. Community programs can be a bridge to healthcare by identifying those with healthcare needs and providing appropriate referrals to culturally sensitive services. Although health centers often exist in impoverished areas, individuals who mistrust healthcare may be unwilling to access them. It is critical to involve community members in program development and implementation to best address such barriers and to establish credibility with hard-to-reach populations.

AIDS service organizations have pioneered community-based outreach programs for increasing HIV testing and supporting treatment adherence and engagement in care among those living with HIV (Mutchler et al., 2011). Through their location outside of the healthcare system, such organizations provide a safe space for individuals who may be too mistrustful to obtain HIV-related services in healthcare establishments. Such programs provide promising future directions for research in reducing mistrust.

Scientists can play a role in reducing mistrust of medical information and research by employing principles of community-based participatory research. In community-based participatory research, community stakeholders (i.e., people affected by HIV disparities) are equitably involved as full partners in all phases of the research, including initial idea and proposal generation, study implementation, and interpretation and dissemination of results (Bogart & Uyeda, 2009). This methodology enhances the transparency of the research process, ultimately facilitating trust in research results and the science behind medical treatments among community stakeholders.

Individual Level: Perceivers

At the individual level among perceivers, the social and clinical psychological literatures suggest interventions that have only recently been applied to the HIV epidemic. These interventions often target social categorization, or grouping people based on common characteristics, given its role in maintaining societal stigma by activating stereotypes and justifying prejudice and discrimination (Link & Phelan, 2001). Social categorization is malleable: How a person categorizes another can be shaped by contextual influences and altered by experience. Interventions that disrupt social categorization by enhancing common ingroup identity and increasing contact between perceivers and targets may reduce prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination thereby reducing the impact of societal stigma manifested at the individual level among perceivers on outcomes relevant to HIV disparities.

Common Ingroup Identity

Prejudice and stereotypes endorsed by healthcare workers can result in poor medical treatment. Creating a common ingroup identity between physicians and patients may help to reduce prejudice, even when implicit, towards people at risk of and living with HIV (Dovidio et al., 2008). The Common Ingroup Identity Model (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2012) posits that social categorization can maintain intergroup bias by separating people into ingroups (i.e., “us”; e.g., Whites, people not living with HIV, physicians) and outgroups (i.e., “them”; e.g., Blacks, people living with HIV, patients). The creation of common groups may help to reduce intergroup bias by encouraging individuals to think of themselves as belonging to a superordinate group. For example, physicians and patients can be encouraged to think of themselves as a team with a shared goal to improve the health of the patient through instructions and written reminders that are reinforced by visual cues such as team colors and paraphernalia (e.g., pens, logos, buttons) (Penner et al., 2013).

Contact

Although faith-based organizations have been criticized as acting as an obstacle to HIV prevention efforts, they have potential for reducing stigma towards people living with HIV due to their prominence in Black and Latino communities (Derose et al., 2010). Research on the contact hypothesis suggests that interactions between congregants and people living with HIV are likely to be effective at reducing prejudice, especially if the interactions are positive and the organizational leadership openly shows support (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). Research might examine whether the effects of contact generalize beyond the immediate context, thereby leading to reductions in prejudice outside of faith-based organizations and into the broader community.

Contact between congregants and people living with HIV may be facilitated in several ways. For example, people living with HIV can be invited to the give a testimonial to the congregation, or church health ministries can facilitate opportunities for congregants to volunteer with AIDS service organizations (Otolok-Tanga, Atuyambe, Murphy, Ringheim, & Woldehanna, 2007). Research can explore whether indirect contact via media (e.g., television, internet) that exposes congregants to people living with HIV can be effective in reducing prejudice in this context, as it has recently been shown to work for racial and ethnic prejudice (Paluck, 2009).

Individual Level: Targets

Targets often thrive under adverse conditions, demonstrating remarkable resilience to societal stigma as well as its manifestations at the structural level and individual level among targets. Interventions that increase social support and improve adaptive coping can improve how targets respond to stigma, disrupting the adverse effects of perceived, internalized, and anticipated stigma on health outcomes relevant to HIV disparities.

Social Support

Support can increase targets’ resilience to stigma by helping to regulate emotions, foster emotional expression, and problem solve (Cohen, 1988). Social support can assist in cognitive restructuring after perceiving discrimination, in which individuals reframe thoughts by making self-protective attributions (e.g., the problem lies with the perceiver rather than the target) (Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998). Because suppression of thoughts about perceived stigma can prolong distress, social support can encourage targets to talk through the event openly (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, 2009). After perceiving stigma, Black adolescents with highly supportive parents report less behavioral willingness to engage in substance use than those with less supportive parents (Gibbons et al., 2010). Research can explore how parents can help adolescents cope with the emotional and cognitive aftermath of perceived stigma, and ultimately possibly prevent engagement in HIV risk behaviors.

Intersectionality can lead to challenges when accessing supportive social networks that stigmatize one or more identities, but lend support for others. Support for all aspects of intersecting identities may not be forthcoming from one source; different sources may stigmatize distinct aspects of identity. Consequently, for example, Black men who have sex with men may camouflage aspects of their identity to gain support from faith-based organizations, in which HIV stigma and homophobia may be present (Bluthenthal et al., 2012). When discriminatory environments are anticipated, men may not disclose their sero-status or sexual orientation (Della, Wilson, & Miller, 2002). Moreover, because people with intersecting identities may hide aspects of their identities, they may have limited opportunities to seek social support from others with the same intersectional identities. Interventions for those with intersecting identities could direct individuals about effective strategies for increasing or leverage existing support resources, especially in the context of low levels of disclosure.

Adaptive Coping

A small research literature has identified culturally relevant resilience strategies used by people with intersecting identities, including affiliation with supportive others who avoid negativity and maladaptive coping (e.g., substance use) among Black men (Teti et al., 2012); and building supportive HIV-positive networks among Black women living with HIV (Logie et al., 2011). Intervention research could test interventions that encourage adaptive strategies. For example, counselors can be trained to reframe individuals’ cognitions about discrimination to elicit thoughts about the consequences of maladaptive (e.g., anger, aggression, substance use) and adaptive (e.g., support seeking) emotions and behaviors that may arise in response to stress from discrimination.

Spirituality, sometimes characterized as a coping resource, also increases resilience to stigma. Chaudoir and colleagues (2011) found that spiritual peace (i.e., a sense of peace and meaning derived from spirituality) buffers people living with HIV from the negative impact of HIV stigma on depression. Duran and Walters (2004) further suggest that spirituality, including engagement in religious rites and ceremonial practices, enhances resilience to historical trauma among American Indians/Alaskan Natives. Future research might evaluate whether spirituality operates as a resilience factor because it restores self-worth (often depleted by internalized stigma) and perceptions of controllability (often depleted by perceived and anticipated stigma).

Implications and Conclusions

HIV is an epidemic fueled, in part, by stigma. Through its structural and individual-level manifestations, societal stigma contributes to racial and ethnic disparities in who acquires HIV, is aware of their sero-status, receives treatment, and dies early. Our objective was to synthesize separate literatures on stigma and HIV disparities and develop an integrative framework for understanding their relationship. This perspective, illustrated in the Stigma and HIV Disparities Model, helps to identify new, fertile avenues for future research and valuable practical implications for the training of health care professionals.

Conceptually, research has traditionally emphasized disparities as a function of race, gender, and other demographic and social categories. Our analysis recognizes the importance of studying the intersectionality of these characteristics (see also Cole, 2009) and suggests that HIV disparities are not monolithic – they do not impact racial/ethnic groups uniformly across the HIV continuum. More nuanced research that attends to intersections of characteristics might help to illuminate the unique psychological vulnerabilities of different intersectional identities to societal stigma and clarify patterns of HIV disparities. Our approach considers structural and individual-level influences, suggesting that future research might attend to how the effectiveness of interventions at one level is affected by influences at the other level. For example, attempts to increase trust and thus adherence by emphasizing common identity between physicians and patients at the individual level (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2012) may be undermined at the structural level by high racial residential segregation that reinforces separate group identities in everyday life. Our strength-based approach also emphasizes the need for a resilience agenda that emphasizes positive goals, motives, and psychological processes – that is, a health-promotion orientation. Future work might evaluate which resources are most effective in overcoming societal stigma at the structural and individual levels.

Our framework has immediate implications for the education and training of health care professionals. Providers can be educated about stigma experienced by populations affected by HIV, as well as the potential consequences of stigma for health behaviors and outcomes. Despite the evidence of disparities in healthcare treatment and interactions, only 55% of White physicians agree that “minority patients generally receive lower quality care than White patients” (AMA/NHMA/NMA Commission to End Health Care Disparities, 2005). Even when physicians become aware of how stigma can contribute to HIV disparities, they may still focus on the single, most contextually-relevant social identity of a person (e.g., race or immigrant status) unless they are motivated to attend to other characteristics (Pendry & Macrae, 1996). Physicians might be trained to form more individuated impressions of patients and appreciate how intersectional identities shape people’s perceptions, experiences, and needs. Such education may also enable health care providers, who may assume the trust of their patients, to understand how structural, historical, and contemporary social influences can lead patients to enter medical encounters with mistrust (Dovidio et al., 2008), and thus help providers develop more effective strategies for engaging patients positively. Finally, rather than viewing people as passive victims of stigma, we conceptualize people as active agents who can access a range of resources to protect themselves. Physicians may be trained to identify and promote resilience resources, such as discussing with patients ways in which they could obtain social support through selective disclosure to individuals who might be less likely to stigmatize.

In conclusion, psychologists can contribute to the elimination of HIV disparities, thereby promoting the achievement of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy. Today’s biomedical prevention strategies have great potential to prevent, treat, and even eliminate HIV: Ground-breaking research shows that HIV transmission is lower among people whose HIV viral load is suppressed from antiretroviral treatment (Cohen et al., 2011), and HIV infection is reduced among at-risk, uninfected individuals who take antiretroviral medications (i.e., preexposure prophylaxis) (Smith et al., 2011). However, such biomedical strategies will not be successful without changing behaviors associated with stigma, including use of and adherence to antiretroviral treatment. Interventions and clinical practice that increase resilience to societal stigma have the capacity to improve these behaviors and ultimately reduce disparities across the HIV continuum.

Acknowledgments

Valerie A. Earnshaw was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant T32 MH020031; Laura M. Bogart, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 MD003964, R01 MD006058, and RC4 HD066907; John F. Dovidio, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01HL 0856331-0182 and 1R01DA029888-01; and David R. Williams, by National Institutes of Health Grants P50 CA148506 and R01 AG038492. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We are grateful to Elizabeth Schink and Caroline Hu for their assistance with literature searches and reviews.

Contributor Information

Valerie A. Earnshaw, Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, Yale University

Laura M. Bogart, Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Harvard University

John F. Dovidio, Department of Psychology, Yale University

Davird R. Williams, Department of African and African American Studies and School of Public Health, Harvard University

References

- AMA/NHMA/NMA Commission to End Health Care Disparities. Preliminary survey brief: Physicians are becoming engaged to address health disparities 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Bird ST, Bogart LM, Delahanty DL. Health-related correlates of perceived discrimination in HIV care. Aids Patient Care and STDS. 2004;18(1):19–26. doi: 10.1089/108729104322740884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN, Palar K, Mendel P, Kanouse DE, Corbin DE, Derose KP. Attitudes and beliefs related to HIV/AIDS in urban religious congregations: Barriers and opportunities for HIV-related interventions. Social Science and Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.020. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Thorburn S. Are HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs a barrier to HIV prevention among African Americans? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;38(2):213–218. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200502010-00014. 00126334-200502010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Uyeda KE. Community-based participatory research: partnering with communities for effective and sustainable behavioral health interventions. Health Psychology. 2009;28(4):391–393. doi: 10.1037/a0016387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Galvan FH, Klein DJ. Longitudinal relationships between antiretroviral treatment adherence and discrimination due to HIV-serostatus, race, and sexual orientation among African-American men with HIV. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40(2):184–190. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9200-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Wagner G, Galvan FH, Banks D. Conspiracy beliefs about HIV are related to antiretroviral treatment nonadherence among African American men with HIV. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;53(5):648–655. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c57dbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV testing survey 2002. HIV/AIDS special surveillance report. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS among American Indians and Alaska Natives. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2009. Vol. 21. Atlanta: Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States: The stages of care. Atlanta: Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir SR, Norton WE, Earnshaw VA, Moneyham L, Mugavero MJ, Hiers KM. Coping with HIV Stigma: Do Proactive Coping and Spiritual Peace Buffer the Effect of Stigma on Depression? AIDS Behavior, Epub. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen NE, Gallant JE, Page KR. A systematic review of HIV/AIDS survival and delayed diagnosis among Hispanics in the United States. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2012;14(1):65–81. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9497-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Fleming TR. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychology. 1988;7(3):269–297. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.7.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist. 2009;64(3):170–180. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, Beach MC, Sabin JA, Greenwald AG, Inui TS. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(5):979–987. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(21):2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B, Steele C. Social stigma. In: Gilbert D, Fiske ST, Linzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4. Vol. 2. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1998. pp. 504–553. [Google Scholar]

- Della B, Wilson M, Miller RL. Strategies for managing heterosexism used among African American gay and bisexual men. Journal of Black Psychology. 2002;28(4):371–391. [Google Scholar]

- Derose KP, Mendel PJ, Kanouse DE, Bluthenthal RN, Castaneda LW, Hawes-Dawson J, Oden CW. Learning about urban congregations and HIV/AIDS: community-based foundations for developing congregational health interventions. Journal of Urban Health. 2010;87(4):617–630. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9444-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E. Sexual risk as an outcome of social oppression: data from a probability sample of Latino gay men in three U.S. cities. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10(3):255–267. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL. Aversive racism. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 36. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2004. pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Norton WE, Gaertner SL, Shelton JN. Disparities and distrust: the implications of psychological processes for understanding racial disparities in health and health care. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67(3):478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran B, Walters KL. HIV/AIDS prevention in “Indian Country”: Current practice, indigenist etiology models, and postcolonial approaches to change. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16(3):187–201. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.3.187.35441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: A review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behavior. 2009;13(6):1160–1177. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9593-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza L, Hall HI, Hu X. Increases in HIV diagnoses at the U.S.-Mexico border, 2003–2006. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21(5 Suppl):19–33. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauth RC, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Short-term effects of moving from public housing in poor to middle-class neighborhoods on low-income, minority adults’ outcomes. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;59(11):2271–2284. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner SL, Dovidio JF. Reducing intergroup bias: The Common Ingroup Identity Model. In: Van Lange PAM, Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, editors. Handbook of theories of social psychology. Vol. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012. pp. 439–457. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Etcheverry PE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng CY, Kiviniemi M, O’Hara RE. Exploring the link between racial discrimination and substance use: What mediates? What buffers? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99(5):785–801. doi: 10.1037/a0019880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RM, Speers MA, McLeroy K, Fawcett S, Kegler M, Parker E, Wallerstein N. Identifying and defining the dimensions of community capacity to provide a basis for measurement. Health Education and Behavior. 1998;25(3):258–278. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harawa NT, Greenland S, Bingham TA, Johnson DF, Cochran SD, Cunningham WE, Valleroy LA. Associations of race/ethnicity with HIV prevalence and HIV-related behaviors among young men who have sex with men in 7 urban centers in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;35(5):526–536. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”?: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science. 2009;20(10):1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. Correlates of African American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: a comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31(1–2):15–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1023066418688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MO, Catz SL, Remien RH, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Morin SF, Charlebois E The NIMH Healthy Living Project Team. Theory-guided, empirically supported avenues for intervention on HIV medication nonadherence: Findings from the Healthy Living Project. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2003;17(3):645–656. doi: 10.1089/108729103771928708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM, Engelman S, Turner CE, Jr, Campbell S. Worlds apart: The universality of racism leads to divergent social realities. In: Demoulin S, Leyens J-P, Dovidio JF, editors. Intergroup misunderstandings: Impact of divergent social realities. New York: Psychology Press; 2009. pp. 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. HIV testing in the United States: HIV/AIDS policy fact sheet. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2011. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Pellowski J, Turner C. Prevalence of sexually transmitted co-infections in people living with HIV/AIDS: systematic review with implications for using HIV treatments for prevention. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2011;87(3):183–190. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.047514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King WD, Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Landon BE, Cunningham WE. Does racial concordance between HIV-positive patients and their physicians affect the time to receipt of protease inhibitors? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19(11):1146–1153. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30443.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsler JJ, Wong MD, Sayles JN, Davis C, Cunningham WE. The effect of perceived stigma from a health care provider on access to care among a low-income HIV-positive population. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2007;21(8):584–592. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV. Monitoring socioeconomic inequalities in sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, and violence: Geocoding and choice of area-based socioeconomic measures--the public health disparities geocoding project (US) Public Health Reports. 2003;118(3):240–260. doi: 10.1093/phr/118.3.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RS, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Internalized stigma among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;6(4):309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J. HIV disease progression: Depression, stress, and possible mechanisms. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:295–306. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie-Blanton M, Stone VE, Snow Jones A, Levi J, Golub ET, Cohen MH, Wilson TE. Association of race, substance abuse, and health insurance coverage with use of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected women, 2005. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(8):1493–1499. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Logie CH, James L, Tharao W, Loutfy MR. HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation, and sex work: A qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV-positive women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Medicine. 2011;8(11):e1001124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losina E, Schackman BR, Sadownik SN, Gebo KA, Walensky RP, Chiosi JJ, Freedberg KA. Racial and sex disparities in life expectancy losses among HIV-infected persons in the United States: Impact of risk behavior, late initiation, and early discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;49(10):1570–1578. doi: 10.1086/644772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Mendes WB, Dovidio JF. Intergroup relations and health disparities: A social psychological perspective. Health Psychology. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0030358. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Norton BL, Kegler MC, Burdine JN, Sumaya CV. Community-based interventions. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(4):529–533. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Roberts KJ, Hoffman D, Molina A, Lu MC. Barriers and successful strategies to antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected monolingual Spanish-speaking patients. AIDS Care. 2003;15(2):217–230. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000068362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler MG, Wagner G, Cowgill BO, McKay T, Risley B, Bogart LM. Improving HIV/AIDS care through treatment advocacy: going beyond client education to empowerment by facilitating client-provider relationships. AIDS Care. 2011;23(1):79–90. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.496847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, & TB Prevention. Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention. HIV surveillance by race/ethnicity. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Obermeyer CM, Osborn M. The utilization of testing and counseling for HIV: A review of the social and behavioral evidence. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(10):1762–1774. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.096263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh DL, Sarafian F, Silvestre A, Brown T, Jacobson L, Badri S, Detels R. Evaluation of adherence and factors affecting adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among White, Hispanic, and Black men in the MACS cohort. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;52(2):290–293. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab6d48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okie S. Sex, drugs, prisons, and HIV. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356(2):105–108. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otolok-Tanga E, Atuyambe L, Murphy CK, Ringheim KE, Woldehanna S. Examining the actions of faith-based organizations and their influence on HIV/AIDS-related stigma: A case study of Uganda. African Health Sciences. 2007;7(1):55–60. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2007.7.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paluck EL. Reducing intergroup prejudice and conflict using the media: A field experiment in Rwanda. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96(3):574–587. doi: 10.1037/a0011989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendry LF, Macrae CN. What the disinterested perceiver overlooks: Goal-directed social categorization. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22(3):249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Penner LA, Gaertner SL, Dovidio JF, Hagiwara N, Porcerelli J, Markova T, Albrecht TL. A social psychological approach to improving the outcomes of racially discordant medical interactions. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2339-y. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90(5):751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, Hall HI. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdie-Vaughns V, Eibach RP. Intersectional invisibility: The distinctive advantages and disadvantages of multiple subordinate-group identities. Sex Roles. 2008;59(5–6):377–391. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9424-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Singer M, Bourgois P, Friedman SR, Strathdee SA. The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61(5):1026–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayles JN, Wong MD, Kinsler JJ, Martins D, Cunningham WE. The association of stigma with self-reported access to medical care and antiretroviral therapy adherence in persons living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(10):1101–1108. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1068-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster MA, Collins RL, Cunningham WE, Morton SC, Zierler S, Wong M, Kanouse DE. Perceived discrimination in clinical care in a nationally representative sample of HIV-infected adults receiving health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20(9):807–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.05049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarcz S, Weinstock H, Louie B, Kellogg T, Douglas J, Lalota M, Bennett D. Characteristics of persons with recently acquired HIV infection: Application of the serologic testing algorithm for recent HIV seroconversion in 10 US cities. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;44(1):112–115. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000247228.30128.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro MF, Morton SC, McCaffrey DF, Senterfitt JW, Fleishman JA, Perlman JF, Bozzette SA. Variations in the care of HIV-infected adults in the United States: Results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281(24):2305–2315. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.24.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, German D, Cheng Y, Marks M, Bailey-Kloche M. The evaluation of the JEWEL project: an innovative economic enhancement and HIV prevention intervention study targeting drug using women involved in prostitution. AIDS Care. 2006;18(1):1–11. doi: 10.1080/09540120600838480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Quesenberry CP, Horberg MA. Race/ethnicity and risk of AIDS and death among HIV-infected patients with access to care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(9):1065–1072. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1049-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard EP, Fransua M, Naishadham D, Jemal A. The influence of sex, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment on Human Immunodeficiency Virus death rates among adults, 1993–2007. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012:e1–e8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DK, Grant RM, Weidle PJ, Lansky A, Mermin J, Fenton KA National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD & TB Prevention, CDC. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. Interim guidance: Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotero MM. A conceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice. 2006;1(1):93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Sternthal MJ, Slopen N, Williams DR. Racial disparities in health: How much does stress really matter? Du Bois Review. 2011;8(1):95–113. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone VE. Physician contributions to disparities in HIV/AIDS care: The role of provider perceptions regarding adherence. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2005;2(4):189–193. doi: 10.1007/s11904-005-0015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Jackson B. Factors affecting alcohol consumption in black women. Part II. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1990;25(12):1415–1427. doi: 10.3109/10826089009056228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti M, Martin AE, Ranade R, Massie J, Malebranche DJ, Tschann JM, Bowleg L. “I’m a keep rising. I’m a keep going forward, regardless”: Exploring Black men’s resilience amid sociostructural challenges and stressors. Qualitative Health Research. 2012;22(4):524–533. doi: 10.1177/1049732311422051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The White House Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy: Federal Implementation Plan. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.whitehouse.gov/files/documents/nhas-implementation.pdf.

- Turner BJ, Cunningham WE, Duan N, Andersen RM, Shapiro MF, Bozzette SA, Zierler S. Delayed medical care after diagnosis in a US national probability sample of persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(17):2614–2622. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.17.2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M. Resilience across cultures. British Journal of Social Work. 2008;38(2):218–235. [Google Scholar]

- Valdiserri RO. HIV/AIDS stigma: An impediment to public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(3):341–342. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, Littlewood RA. Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(5):473–482. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9099-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Beltran R, Huh D, Evans-Campbell T. Displacement and disease: Land, place, and health among American Indians and Alaska Natives. In: Burton LM, Matthews SA, Leung M, Kemp SP, Takeuchi DT, editors. Communities, neighborhoods, and health. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 163–199. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Adams GW, Hoyt DR, Chen X. Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among American Indian people. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33(3–4):119–130. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027000.77357.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K, Haas JS, Williams DR. Elucidating the Role of Place in Health Care Disparities: The Example of Racial/Ethnic Residential Segregation. Health Services Research. 2012;47(3 Pt 2):1278–1299. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(5):404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]