Abstract

Purpose

Immune-related response criteria (irRC) was developed to adequately assess tumor response to immunotherapy. The irRC are based on bidimensional measurements, as opposed to unidimensional measurements defined by RECIST, which has been widely used in solid tumors. We aimed to compare response assessment by bidimensional versus unidimensional irRC in advanced melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab.

Methods

Fifty-seven patients with advanced melanoma treated with ipilimumab in a phase II, expanded access trial were studied. Bidimensional tumor measurement records prospectively performed during the trial were reviewed to generate a second set of measurements using unidimensional, longest diameter measurements. The percent changes of measurements at follow-up, best overall response, and time-to-progression (TTP) were compared between bidimensional and unidimensional irRC. Interobserver variability for bidimensional and unidimensional measurements was assessed in randomly selected 25 patients.

Results

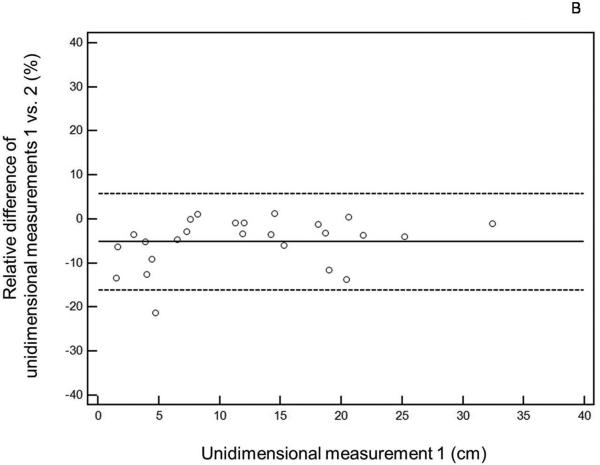

The percent changes at follow-up scans were highly concordant between the two criteria (Spearman r: 0.953-0.965, 1st −4th follow-up). The best immune-related response was highly concordant between the two criteria (κw=0.881). TTP was similar between the bidmensional and unidimensional assessments (progression-free at 6 months: 70% versus 81%, respectively). The unidimensional measurements were more reproducible than bidimensional measurements, with the 95% limits of agreement of (−16.1%, 5.8%) versus (−31.3%, 19.7%), respectively.

Conclusion

Immune-related response criteria using the unidimensional measurements provided highly concordant response assessment compared to the bidimensional irRC, with less measurement variability. The use of unidimensional irRC is proposed to assess response to immunotherapy in solid tumors, given its simplicity, higher reproducibility and high concordance with the bidimensional irRC.

Keywords: melanoma, immunotherapy, tumor response, tumor measurements, immune-related response criteria

INTRODUCTION

The recent increasing understanding of regulatory pathways of the immune response to cancer has led to the development and application of immunotherapeutic agents. Ipilimumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody and blocks the binding of CTLA-4 to its ligands [1-5]. Ipilimumab has shown to significantly improve overall survival in metastatic melanoma patients in a randomized phase 3 trial, and has been approved for treatment of advanced melanoma [1]. Ipilimumab is currently tested and has shown efficacy in other solid tumors including in non-small-cell lung cancer [6].

Immunotherapeutic agents such as ipilimumab exerts the anti-tumor activity by augmenting activation and proliferation of T cells, which leads to tumor infiltration by T cells and tumor regression rather than direct cytotoxic effects [1-5]. Clinical observations of advanced melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab suggested that conventional response assessment criteria such as RECIST and WHO criteria are not sufficient to fully characterize patterns of tumor response to immunotherapy, because tumors treated with immunotherapeutic agents may demonstrate additional response patterns that are not described in these conventional criteria [7, 8]. Given the background, a novel set of criteria developed to capture additional response patterns was proposed as “immune-related response criteria (irRC)” in 2009, based on the discussion by 200 oncologists, immunotherapists, and regulatory experts [7]. The irRC were evaluated in large, multinational studies, involving 487 patients with advanced melanoma who received ipilimumab [7]. Recent phase 2 trial of ipilimumab in NSCLC utilized irRC to assess response and define endpoints [6].

The irRC published in 2009 was based on the modified WHO criteria, and utilize bidimensional tumor measurements of target lesions, which is obtained by multiplying the longest diameter and the longest perpendicular diameter of each lesion [7]. However, most trials of solid tumors in the past decade have used RECIST guidelines, which utilizes unidimensional, longest diameter measurements [9-11]. To directly compare the efficacy and effectiveness of anti-cancer agents, unifying the measurement method in tumor response assessment is of great importance. In addition, multiple reports have demonstrated unidimensional measurements are more reproducible and therefore have less misclassification rate for response assessment compared to bidimensional measurements [12-14].

As emphasized in the publication of WHO criteria by Miller et al in 1981 in Cancer, tumor response criteria were developed due to the necessity of a “common language” to describe the results of cancer treatment and provide basis for advances in cancer therapy [15]. Given the promising efficacy of newer immunotherapeutic agents, such as anti-PD-1 antibody in melanoma as well as in other solid tumors including NSCLC and renal cell carcinoma (RCC), it is necessary to develop a “common language” for immune-related tumor response assessment to further move the field forward.

In the present study, we hypothesized that the immune-related response criteria using unidimensional measurements can provide response assessment concordant with the original irRC with bidimensional measurements. We also hypothesized that the unidimensional measurements has less measurement variability than the bidimensional measurements. If these hypotheses are proven, we propose to utilize unidimensional, longest diameter measurements in irRC to assess efficacy and effectiveness of immunotherapeutic agents, which are simpler and more reproducible, and provide response assessment that can be directly compared with the results from trials in the past decade.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

The study population included 57 patients (36 men and 21 women; mean age, 64 years; range, 39-87 years), with advanced melanoma treated with ipilimumab at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in a phase 2, multicenter treatment protocol for expanded access of ipilimumab monotherapy in subjects with histologically confirmed unresectable stage III or stage IV melanoma, whose prospective tumor measurement tables at baseline and at least one follow-up CT scan were available for review. In this expanded access program, the dose of ipilimumab was 10 mg/kg initially and then changed to 3mg/kg. The protocol was approved by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center institutional review board, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Tumor response assessment

Tumor measurements were performed prospectively during the trial by staff radiologists at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute at the baseline and at every follow-up CT. Follow-up scans were performed at every 12 weeks in principle, while shorter interval follow-up (i.e., 4 weeks) were performed if necessary for the purposes such as confirmation of response or progression. Tumor measurement records included the number of the treatment cycle, the date of assessment, the method of imaging, the target lesion description and bidimensional measurements, the sum of the target lesion measurements (and new lesions if any), descriptions of non-target lesions, the presence or absence of new lesions with their bidimensional measurements if present. These records were retrospectively reviewed by a board-certified radiologist (M.N.) with 8 years of experience in oncologic imaging, to generate a second set of tumor measurements utilizing the unidimensional, longest diameter measurements [7, 16].

The overall approach for measurements and response assessment is summarized in Table 1. In brief, all the tumor measurements in each patient were reviewed and the longest diameter of each target lesion was recorded at baseline and all follow-up studies. Measurable lesions were defined as ≥10 mm in the longest diameter as in RECIST [9-11], as opposed to ≥5×5 mm in WHO/irRC [7, 15]. The longest diameters of new lesions, if any, were also measured, according to irRC. The sum of the longest diameters of all target lesions (and new lesions, if any) was calculated at baseline and each follow-up study, and the percent changes were calculated.

Table 1.

Summary of measurement and response assessment approaches for bidimensional and unidimensional assessment based on irRC

| Bidimensional assessment (the original irRC [7]) | Unidimensioal assessment | |

|---|---|---|

| Measurable lesions | ≥5×5 mm by bidimensional measurements | ≥10 mm in the longest diameter |

| Measurement of each lesion | The longest diameter × the longest perpendicular diameter (cm2) | The longest diameter (cm) |

| The sum of the measurements | The sum of the bidimensional measurements of all target lesions and new lesions if any | The sum of the longest diameters of all target lesions and new lesions if any |

| Response assessment | PD: ≥25% increase from the nadir PR: ≥50% decrease from baseline CR: Disappearance of all lesions |

PD: ≥20% increase from the nadir PR: ≥30% decrease from baseline CR: Disappearance of all lesions |

| New lesions | The presence of new lesion(s) does not define progression. The measurements of the new lesion(s) are included in the sum of the measurements. | |

| Confirmation | Confirmation by two consecutive observations not less than 4 weeks apart was required for CR, PR and PD | |

Response assessment was assigned at each follow-up for bidimensional and unidimensional measurements. For bidimensional measurements, the cut-off values defined by irRC were used (≥25% increase from the nadir for progression, ≥50% decrease from baseline for partial response, and disappearance of all lesions for complete remission) [7]. For unidimensional measurements, the cut-off values by RECIST (≥20% increase from the nadir for progression, ≥30% decrease from baseline for partial response, and disappearance of all lesions for complete remission) were used. Confirmation by two consecutive observations not less than 4 weeks apart was required for CR, PR and PD for both assessments, as defined by irRC to assign best response for each patient (Table 1). The unidimensional immune-related assessment in the present study was carefully designed so that it maintains important features of irRC such as inclusion of new lesion measurements and confirmation of progression, while utilizing the longest diameter measurements as described in RECIST.

Reproducibility of bidimensional versus unidimensional measurements

To assess reproducibility of measurements, a board-certified radiologist (M.N.) performed tumor measurements of target lesions on baseline scans in a randomly selected 25 patients among the study population, whose baseline tumor measurements during trials were performed by staff radiologists other than the radiologist (M.N.). The random selection of 25 patients were made by generating a random sequence of 57 integers from 1 to 57, which corresponded to the study identification numbers of the 57 patients in the study cohort, using a random number generator (www.random.org). The first 25 numbers of the sequence were used to select 25 patients with the corresponding study identification numbers. Just like the measurements during the trial, the radiologist performed bidimensional measurements of the target lesions that have been already selected during trials [16]. Tumor table templates indicating the location, description, and series and image numbers of target lesions (such as “segment IV liver lesion, series 2, image 25”) for the baseline scans were provided to the radiologists, who was not allowed to access the original measurements during trial. Measurements were performed using a measurement tool on PACS workstation (Centricity, GE Healthcare), which was also used for the original measurements during the trials. The sum of the bidimensional and unidimensional measurements was recorded for each patient.

Statistical analysis

The percentage change on follow-up scans by the bidimensional tumor measurements record versus the unidimensional measurements record was compared using Spearman correlation. A weighted kappa analysis was performed to assess the level of agreement between best responses by the bidimensional versus unidimensional measurements using Fleiss-Cohen quadratic weights. Quadratic weights were chosen because a difference between PR and SD is conventionally less important than a difference between SD and PD; patients remain on trial (and on therapy) with PR or SD, while they are removed from trial (and often off the therapy as well) with PD. Agreement between the two assessments was categorized as poor (κw < 0), slight (κw = 0–0.20), fair (κw = 0.21–0.40), moderate (κw =0.41–0.60), substantial (κw = 0.61–0.80), and almost perfect (κw > 0.80). Response assessment results at the 1st, 2nd and third follow-up scans by two measurements were also compared by weighted kappa analysis. Time to progression (TTP) according to two measurement records was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method [17].

Interobserver variability was assessed using concordance correlation coefficients (CCCs), mean relative difference (%), and 95% limits of agreement (%), for the unidimensional, longest diameter (cm) and the bidimensional measurements. CCC was used to assess reproducibility of two measurements, as described previously [13-14]. Assuming two measurements have mean u1 and u2, with variance σ12, σ22, and covariance σ12, CCC = (2 σ12)/[σ12+σ22+(u1-u2)2]. CCCs are composed of a measure of precision (how far each pair of measurements deviates from the best-fit line through the data) and a measure of accuracy (the distance between the best-fit line and the 45 line through the origin). A value of 1 indicates perfect agreement and −1 indicates perfect reversed agreement [18]. Agreement in the two measurements was shown visually using Bland-Altman plots with 95% limits of agreement and the average relative difference, computing the mean relative difference (%) between the two measurements (100*[M1-M2]/M1; M1=Measurements during trial, M2=Measurements by the radiologist in this study) [14]. All p values are based on a two-sided hypothesis. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Bidimensional vs. unidimensional tumor response assessment

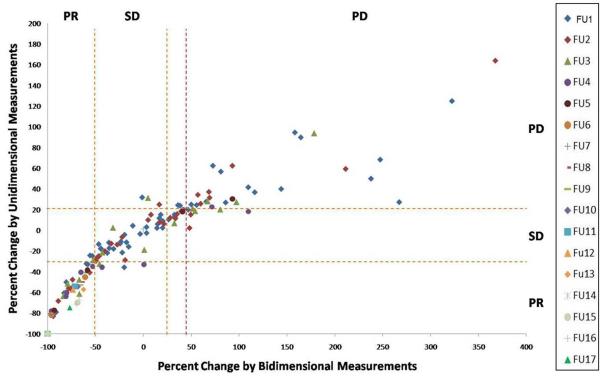

Figure 1 demonstrates the percent changes according to bidimensional and unidimensional measurements at each follow-up scan, including the 1st to 17th follow-up (f/u) scans. The percent changes by two measurements were highly concordant, with Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.959 [95%CI: 0.93-0.98] for the 1st f/u (n=57); 0.963 [0.92-0.98] for the 2nd f/u (n=33); 0.953 [0.88-0.98] for the 3rd f/u (n=21); and 0.965 [0.87-0.99] for the 4th f/u (n=12). The number of patients were too small (≤5) after the 4th follow-up to obtain a reliable estimate. Response assessment results by two measurements on the first three follow-up scans had almost perfect agreement, with κw values of 0.844 for the 1st (n=57), 0.830 for the 2nd (n=33), and 0.861 (n=21) for the 3rd follow-up (Fig. 1, 2).

Fig. 1.

The percent changes according to bidimensional and unidimensional measurements at each follow-up scan from the 1st to 17th follow-up scans.

The orange dashed lines represent the cutoff values for response and progression (−50% and +25% for bidimensional measurements, −30% and +20% for unidimensional measurements). The observations within the lower left, middle center, and upper right boxes have concordant assessment between tow measurements, while observations in other boxes have discordant assessment.

The purple dashed line represents +44% change for bidimensional measurements, which corresponds to +20% change for unidimensional measurements, which was given to visually demonstrate that more observations are concordant if this cut-off value is used.

The percent changes presented in the figure are in comparison with baseline measurements when tumors are decreasing to assess response, and in comparison with the nadir (the smallest measurement since baseline) when tumors are increasing to assess progression. These values are displayed since they are used to define response/progression in patients at the time of response assessment.

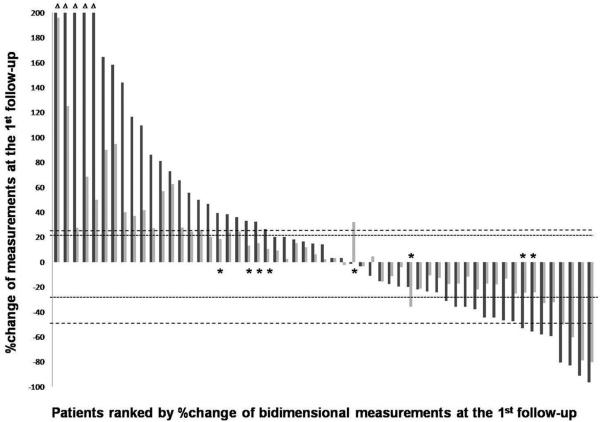

Fig. 2.

The waterfall plot of the percent change of bidimensional and unidimensional measurements at the first follow-up.

Dark gray bars represent the percent changes by bidimensional measurements, and light gray bars represent the percent change by unidimensional measurements. Dashed lines demonstrate cut-off values for bidimensional response and progression (−50% and +25%). Dotted lines demonstrate cut-off values for unidimensional response and progression (−30% and +20%). Response assessment at the 1st follow-up by two assessments had almost perfect agreement (weighted κ = 0.844). Eight patients with discordant assessment are marked with asterisks (*). The first 5 patients (Δ) had bidimensional changes >200% (range: 238-768%).

The best immune-related response according to two measurements showed almost perfect agreement between the two criteria (κw=0.881, Table 2). Best response assessments by two criteria were identical in 53 of 57 patients (93%). The remaining 4 patients (7.0%) had discordant results, including 3 with irPD by bidimensional measurements and irSD by unidimensional measurements, and one with irSD by bidimensional measurements and irPD by unidimensional measurements. 41 patients (72%) had irSD as the best immune-related response according to both measurements.

Table 2.

Best immune-related response according to bidimensional vs. unidimensional assessment

| Best response by unidimensional assessment | Best response by bidimensional Assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| irCR | irPR | irSD | irPD | |

| irCR | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| irPR | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| irSD | 0 | 0 | 41 | 3 |

| irPD | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

(κw =0.881)

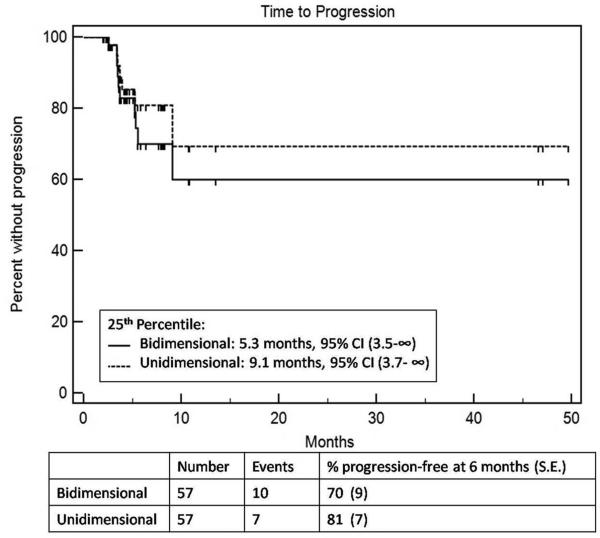

Kaplan-Meier estimates of TTP are shown in Figure 3. At 6 months, 70% of patients were found to be free of progression using the bidimensional assessment, compared with 81% using the unidimensional assessment. Estimates of the 25th percentile (time point at which 75% are free of progression) were 5.3 months (95%CI: 3.5-∞) by bidimensional assessment versus 9.1 months (95%CI: 3.7- ∞) by unidimensional assessment. Based on the almost identical confidence intervals for the 25 percentile, there is no evidence of a difference in TTP between the two methods of assessment.

Fig. 3.

Time to progression according to bidimensional vs. unidimensional assessment.

Reproducibility of bidimensional vs. unidimensional measurements

In randomly selected 25 patients, the CCCs between the measurements performed during the trial and the measurements by the radiologist performed in this study were 0.986 (95%CI: 0.972 – 0.993) for bidimensional measurements, and 0.995 (95%CI: 0.989 – 0.998) for unidimensional measurements (Table 3).

Table 3.

Interobserver measurement variability

| CCC [95% CI] | Mean relative difference (%) | 95% limits of agreement (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bidimensional measurements | 0.986 [0.972 – 0.993] | −5.8 | −31.3, 19.7 |

| Unidimensional measurements | 0.995 [0.989 – 0.998] | −5.1 | −16.1, 5.8 |

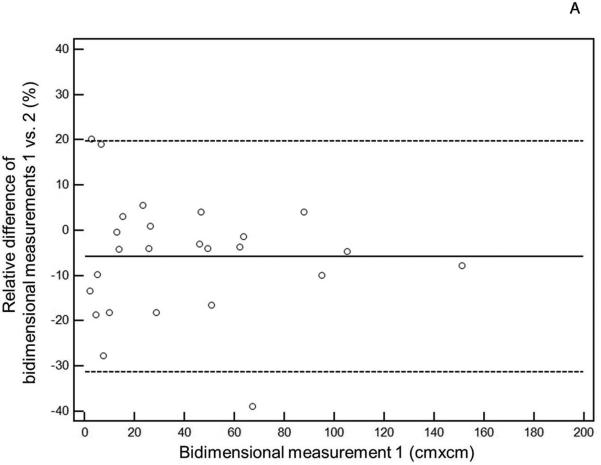

Bland-Altman plots with 95% limits of agreement and the average relative difference are shown in Figure 4. The 95% limits of agreement of bidimensional measurements were (−31.3%, 19.7%), that were twice wider compared to (−16.1%, 5.8%) for unidimensional measurements.

Fig. 4.

Interobserver variability of bidimensional and unidimensional measurements Bland-Altman plots demonstrate interobserver variability of bidimensional and unidimensional measurements on baseline scans in 25 patients. The 95% limits of agreement of bidimensional measurements were (−31.3%, 19.7%; Fig 4A, dashed lines), that were twice wider compared to those of unidimensional measurements (−16.1%, 5.8%; Fig. 4B, dashed lines). The dotted lines represent the mean relative difference (%).

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated that the immune-related response assessment using unidimensional, longest diameter measurements was highly concordant with the assessment based on bidimensional measurements in advanced melanoma patients treated in a clinical trial of ipilimumab. The unidimensional measurements had less measurement variability than bidimensional measurements. The results of the study provide a basis for utilizing unidimensional measurements in immune-related tumor response assessment. The study also serves as an initial step to further optimize response assessment in patients treated with immunothrapeutic agents, towards developing a “common language” for immune-related response.

Highly concordant response assessment at each follow-up between bidimensional and unidimensional measurements was noted, with almost perfect agreement between response assessment categories by two assessments at the first 3 follow-up scans, which was consistent with our initial expectation. Of note, the high concordance was demonstrated in spite of the difference of the cut-off value scales for progression according to bidimensional and unidimensional assessment. 20% increase in unidimensional measurements corresponds to 44% increase in bidimensional measurements, according to the mathematical conversion provided by RECIST [9]. As shown in Figure 1, the use of the scaled value of 44% for progression by bidimensional measurements would have resulted in even higher agreement between the two assessments. On the other hand, 25% increase by bidimensional measurements corresponds to approximately 12% increase by unidimensional measurements. We did not apply this scaled value due to the concern that 12% unidimensional increase is within the measurement variability and therefore can be attributed to measurement error rather than true increase of tumor, which was supported by the reproducibility results of the present study.

Best immune-related response had almost perfect agreement by weighted kappa analysis, which was consistent with our hypothesis. Most patients (41/57, 72%) in the study had the best response of irSD by both assessments, because of the requirement of confirmation for irCR, irPR and irPD. All 4 patients with discordant best immune-related response were in irPD versus irSD categories, with 3 patients having irPD by bidimensional assessment while they had irSD by unidimensional assessment. Among these 3 patients, one patient was alive after 36.4 months since the initiation of therapy, which was three times longer than the median OS of 10.1 months [95%CI: 8.0-13.8] in a phase 3 trial of ipilimumab in melanoma patients [1]. Other 2 patients died after 13.3 months and after 8.4 months, which were within the 95%CI of the reported median OS [1]. One patient with irSD by bidimensional assessment and irPD by unidimensional assessment died after 22.5 months since the initiation of therapy. The data from the small cohort evaluated by this retrospective study are limited to address the important question of association between survival and response assessment. The question needs to be addressed in a larger prospective cohort. The discordance could also be related to the difference in cut-off values, since bidimensional 25% increase may require smaller increase than unidimensional 20% increase. Requiring smaller increase for progression is subject to higher rate of misclassification due to measurement variability, especially when the cut-off values are within the range of measurement errors [12].

There was no evidence of a difference in TTP by two criteria, however, the majority of patients did not progress during the study and therefore censored by both assessments. This is partly due to the requirement of confirmation for all categories except for irSD, which is one of the unique features of irRC. Due to the same reason, median TTP could not be obtained, which is one of the limitations of the present study. We followed this requirement since it was implemented to capture additional response pattern specific to immunotherapy, i.e., decrease of tumor burden after initial progression.

Unidimensional measurements were more reproducible than bidimensional measurements, which was concordant with our initial hypothesis as well as previous reports [12-14]. The 95% limits of agreement for bidimensional measurements were twice larger than those for unidimensional measurements. It should also be noted that 25% change for bidimensional measurements are within the measurement error, and therefore cannot be reliably used to define progression. On the other hand, the cut-off values for the percent change applied for the unidimensional measurements (−30% for PR and +20% for PD) were beyond the range of measurement variability and therefore can be considered to reflect true change of tumor burden, rather than measurement error [12-14].

The cut-off values used for unidimensional measurements in the present study were based on RECIST guidelines (−30% for PR and +20% for PD) [9-10]. We chose these cut-off values because 1) these values are widely accepted in response assessment using unidimensional measurements, and 2) the results obtained using these values can be directly compared to the results of prior trials and studies based on RECIST [10]. The capability of directly comparing the trial results in patients with other solid tumors with other systemic anti-cancer agents are becoming increasingly important as newer immunotherapeutic agents are tested and approved for a variety of solid tumors [19-20].

The current study assessed the measurement variability of randomly selected 25 patients. We based this approach on past investigations demonstrating that unidimensional measurements were more reproducible than bidimensional measurements. Measurement variability is an important issue in the context of defining the adequate cut-off value for response and progression, and remains to be systematically investigated in a larger population of patients during immunotherapy.

Limitations for this analysis include the retrospective design for the unidimensional response assessment. However, the tumor measurement records used in the study were prospectively acquired during the trial. The number of patients included in the analysis was relatively small and was from a single institution. The association between clinical outcome and response assessment results needs to be investigated, which constitutes an important next step to establish an appropriate surrogate marker in cancer immunotherapy.

In conclusion, the immune-related response criteria using unidimensional tumor measurements provided highly concordant response assessment and had less measurement variability compared to the irRC with bidimensional measurements. Additional investigation is warranted to in a larger cohort with correlations with clinical outcomes and assessments by multiple radiologists for reproducibility, to propose the longest axis measurements for tumor response assessment during immunothreapy. It is also necessary to test our observations in patients with other solid tumors treated with other immunotherapeutic agents, to evaluate the broader applicability of the results. We are currently planning to validate the observation in a larger cohort, and to systematically investigate the measurement variability to determine adequate cut-off values for response and progression to accurately characterize immune-related response and progression during immunotherapy.

Translational Relevance.

Given the increasing evidence of the benefits of immunotherapeutic agents in patients with melanoma and other solid malignancies, unifying the strategy to assess response to immunotherapy is essential to provide a “common language” to describe treatment results and provide basis for further advances in cancer immunotherapy. By systematically investigating the tumor measurements record during a prospective phase 2 trial of ipilimumab in advanced melanoma patients, the present study demonstrated that immune-related response criteria (irRC) using unidimensional, the longest diameter measurements provide highly concordant response assessment with better reproducibility compared to the irRC using bidimensional measurements as originally proposed. The study provides a basis for the direction toward unidimensional irRC, which is simple and practical, and provides response assessment that can be directly compared to the results from other trials based on unidimensional, RECIST-based assessment in the past decade.

Acknowledgments

The investigator, M.N., was supported by 1K23CA157631 (NCI) and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Fellowship for the Eleanor and Miles Shore 50th Anniversary Fellowship Program.

Footnotes

Dr. Nikhil H. Ramaiya and Dr. F. Stephen Hodi contributed equally to this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest:

Mizuki Nishino, M.D., Nikhil H. Ramaiya, M.D., Anita Giobbie-Hurder, M.S., Maria Gargano, Margaret Suda: Nothing to disclose

F. Stephen Hodi, M.D.: Dr. Hodi has served as a non-paid consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb and has received clinical trial support from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

References

- 1.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber J, Thompson JA, Hamid O, Minor D, Amin A, Ron I, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, phase II study comparing the tolerability and efficacy of ipilimumab administered with or without prophylactic budesonide in patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5591–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolchok JD, Neyns B, Linette G, Negrier S, Lutzky J, Thomas L, et al. Ipilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2, dose-ranging study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:155–64. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Day, Maio M, Ciarion-Sileni V, Gajewski TF, Pehamberger H, Bondarenko IN, et al. Efficacy and safety of ipilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: a multicenter single-arm phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2010 Aug;21(8):1712–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hodi FS, Butler M, Oble DA, Seiden MV, Haluska FG, Kruse A, et al. Immunologic and clinical effects of antibody blockade of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 in previously vaccinated cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3005–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712237105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynch TJ, Bondarenko I, Luft A, Lynch TJ, Bondarenko I, Luft A, et al. Ipilimumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin as first-line treatment in stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2046–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolchok JD, Hoos A, O'Day S, Weber JS, Hamid O, Lebbé C, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clin Cancer Res. 2009 Dec 1;15(23):7412–20. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishino M, Jagannathan JP, Krajewski KM, O'Regan K, Hatabu H, Shapiro G, et al. Personalized tumor response assessment in the era of molecular medicine: cancer-specific and therapy-specific response criteria to complement pitfalls of RECIST. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:737–45. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumors: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishino M, Jagannathan JP, Ramaiya N, Van den Abbeele AD. Pictorial review of the new Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors: revised RECIST guideline version 1.1 – What oncologists want to know and what radiologists need to know. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:281–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erasmus JJ, Gladish GW, Broemeling L, Sabloff BS, Truong MT, Herbst RS, et al. Interobserver and intraobserver variability in measurement of non-small-cell carcinoma lung lesions: implications for assessment of tumor response. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2574–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao B, James LP, Moskowitz CS, Guo P, Ginsberg MS, Lefkowitz RA, et al. Evaluating variability in tumor measurements from same-day repeat CT scans of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Radiology. 2009;252:263–272. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2522081593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishino M, Guo M, Jackman DM, DiPiro PJ, Yap JT, Ho TK, et al. CT Tumor Volume Measurement in Advanced Non-small-cell Lung Cancer: Performance Characteristics of Emerging Clinical Tool. Acad Radiol. 2011;18:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, Winkler A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer. 1981;47:207–214. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810101)47:1<207::aid-cncr2820470134>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishino M, Jackman DM, Hatabu H, Yeap BY, Cioffredi LA, Yap JT, et al. New Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: comparison with original RECIST and impact on assessment of tumor response to targeted therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:W221–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin LI. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics. 1989;45:255–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]