Abstract

One explanation of the abrupt cooling episode known as the Younger Dryas (YD) is a cosmic impact or airburst at the YD boundary (YDB) that triggered cooling and resulted in other calamities, including the disappearance of the Clovis culture and the extinction of many large mammal species. We tested the YDB impact hypothesis by analyzing ice samples from the Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2 (GISP2) ice core across the Bølling-Allerød/YD boundary for major and trace elements. We found a large Pt anomaly at the YDB, not accompanied by a prominent Ir anomaly, with the Pt/Ir ratios at the Pt peak exceeding those in known terrestrial and extraterrestrial materials. Whereas the highly fractionated Pt/Ir ratio rules out mantle or chondritic sources of the Pt anomaly, it does not allow positive identification of the source. Circumstantial evidence such as very high, superchondritic Pt/Al ratios associated with the Pt anomaly and its timing, different from other major events recorded on the GISP2 ice core such as well-understood sulfate spikes caused by volcanic activity and the ammonium and nitrate spike due to the biomass destruction, hints for an extraterrestrial source of Pt. Such a source could have been a highly differentiated object like an Ir-poor iron meteorite that is unlikely to result in an airburst or trigger wide wildfires proposed by the YDB impact hypothesis.

Keywords: meteorite impact, climate change, ICP-MS analysis, PGE

The Younger Dryas (YD), a millennium-long cooling period amid postglacial warming well documented in the Greenland ice cores (e.g., refs. 1, 2), is thought to result from an abrupt change in atmospheric and oceanic circulation (3). Whether such a change was caused by a catastrophic event or it is an integral, although still poorly understood, feature of the deglaciation process remains unclear (4).

Among testable catastrophic hypotheses, the most popular, attractive, and long-lasting idea of a sudden discharge of fresh water from the proglacial Lake Agassiz into the Arctic Ocean (5–7) eventually was found inconsistent with geomorphological and chronological data (4, 8). The long-term effect of the proposed “volcanic winter” in the northern hemisphere induced by the catastrophic eruption of the Laacher See volcano 12,916 calendar years before 1950 (cal BP) (9) is not clear as the Laacher See tephra, found in many European lacustrine deposits, is absent in the Greenland ice cores (10). The impact hypothesis (11), once declared dead (12, 13), recently gained new support from the discovery of siliceous scoria-like objects (SLOs) with global distribution, which provide strong evidence for processing at high temperatures and pressures consistent with a cosmic impact (14).

The ever-controversial impact hypothesis was initially invoked to explain the disappearance of the Clovis culture and the extinction of many mammal species, including mammoths, by a cometary airburst that resulted in massive wildfires and, ultimately, the YD cooling. A C-rich layer exposed at many sites in North America and Europe at or near the YD boundary (YDB layer), which is enriched in magnetic grains with Ir, magnetic microspherules, charcoal, soot, carbon spherules, glass-like carbon with nanodiamonds, and fullerenes with extraterrestrial He (11), has been interpreted as documenting this event. Ammonium and nitrate spikes at the onset of the YD in Greenland Ice Core Project (GRIP) and Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2 (GISP2) ice cores, perhaps resulting from biomass burning, are taken as further support for the impact hypothesis. Subsequent studies (13, 15, 16) questioned the origins of many impact markers cited by ref. 11, but the discovery of the SLOs alongside abundant, compositionally similar microspherules in three YDB sites in North America and Asia is difficult to explain by anything other than a cosmic impact. In its latest incarnation, the impact hypothesis calls for three or more epicenters of an impact or airburst (14). However, the invoked markers have never been supported by a clear geochemical impact signature such as a sharp increase in Ir or other platinum group element (PGE) concentrations at the YDB.

We have tested the YDB impact hypothesis by measuring trace and major element concentrations in ice samples from the GISP2 ice core across the Bølling-Allerød/YD boundary (depth of 1,709–1,720 m, 12,279–13,064 cal BP) with a spatial resolution of ∼12.5 cm, corresponding to a time resolution of 2.5–4.6 y (17). The elemental concentrations in melted ice samples were measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) that is known to have possible interferences of LuO and HfO peaks with Ir and Pt peaks. This issue was resolved by measuring Lu and Hf oxide formation in well-calibrated standards (details in Materials and Methods).

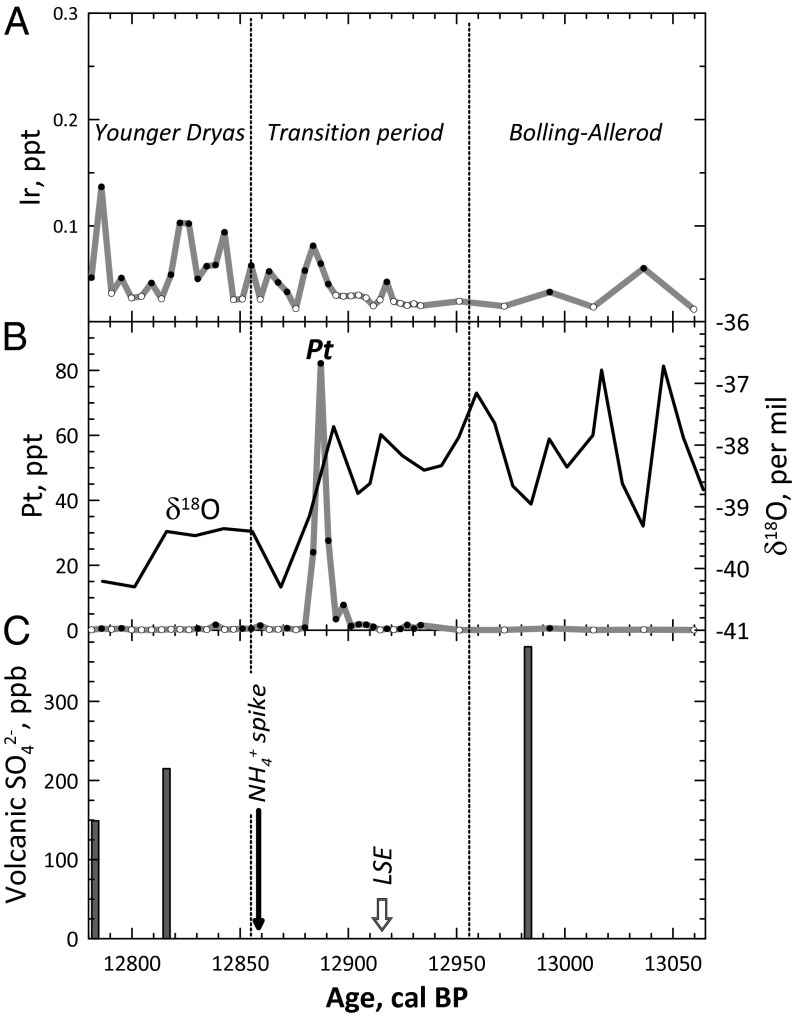

The major finding of this study (Fig. 1 and Table S1) is the lack of a striking Ir anomaly in the analyzed ice samples. Instead, we found a large Pt anomaly in the middle of the Bølling-Allerød–YD transition that is contemporaneous with a sharp drop in the δ18O values (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1). The Pt peak (Fig. 1) is unlikely to be a mass-spectrometry artifact because (a) it is smoothly defined by seven ice samples; (b) the HfO interferences (178Hf16O, 179Hf16O, 180Hf16O) on 194,195,196Pt isotopes, respectively, were carefully assessed; (c) the 178,179,180Hf signals in sample 63 with the highest Pt concentration are at least a factor of 10 lower than those of 194,195,196Pt; and (d) there is no linear correlation between Hf concentrations and Pt concentrations in the ice samples.

Fig. 1.

(A and B) Ir (A) and Pt (B) variations in the GISP2 ice samples across the Bølling-Allerød/YD boundary. Open symbols indicate upper limits. During the transitional period the annual rate of ice accumulation changes from high to low values (1). The Ir contents in the ice (A) show some variations with no clear substantial anomalies. On the contrary, a large Pt anomaly (B) occurs in the middle of the Bølling-Allerød–YD transition period. The anomaly coincides with a sharp drop in the δ18O values in ice (black curve). The δ18O curve is calculated from the data of ref. 18 averaged for 40 cm of ice thickness. (C) The time of the Pt anomaly differs from those of the volcanic SO42− spikes (19) and the Laacher See eruption (LSE) (9) and precedes the onset of the NH4+ spike (2) by ∼30 y.

The Pt concentrations gradually rise by at least 100-fold over ∼14 y and drop back during the subsequent ∼7 y. The decay of the Pt signal is consistent with the ∼5-y lifetime of dust in the stratosphere. The observed gradual ingrowth of the Pt concentration in ice over ∼14 y may suggest multiple injections of Pt-rich dust into the stratosphere that are expected to result in a global Pt anomaly.

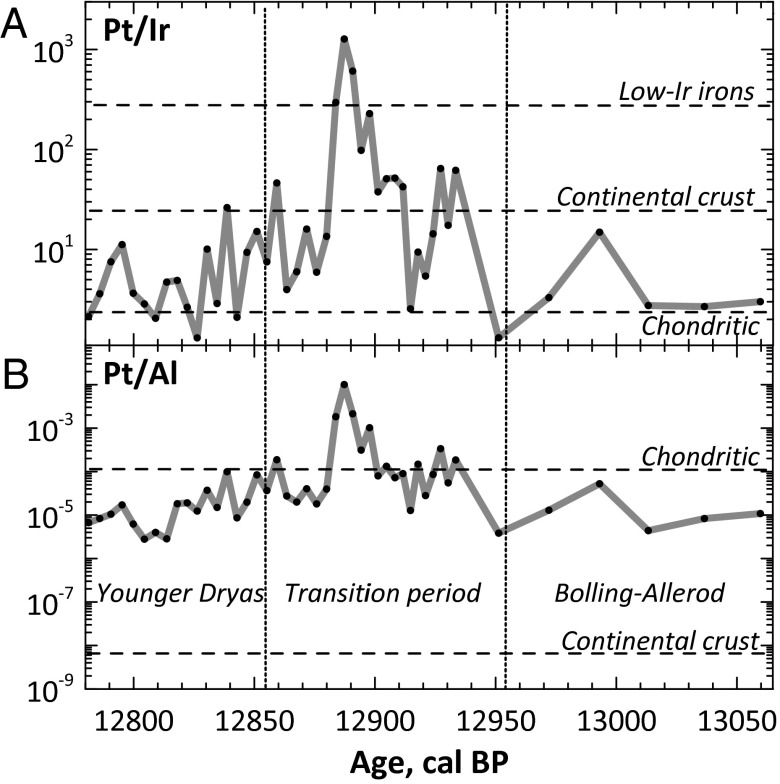

The Pt anomaly is accompanied by extremely high Pt/Ir and Pt/Al ratios (Fig. 2), indicative of a highly unusual source of Pt in the ice. Such a source is unlikely to be laboratory contamination because (a) all samples defining the anomaly are from the same ice core samples (Fig. S2) and were collected using the same set of tools and latex gloves, (b) three peak samples are from a single continuous chunk, and (c) the samples were randomly dissolved and analyzed. Contamination during ice coring and subsequent slicing is also unlikely because PGEs are essentially insoluble in pure acids, let alone in water (Materials and Methods).

Fig. 2.

(A and B) Pt/Ir (A) and Pt/Al (B) ratios in the GISP2 ice samples across the Bølling-Allerød/YD boundary vary between the chondritic and continental crust values. The only exception is the Pt anomaly with both Pt/Ir and Pt/Al ratios greatly exceeding chondritic and crustal values, with three top points also exceeding Pt/Ir ratios of low-Ir iron meteorites. Such a large fractionation of both Pt/Ir and Pt/Al ratios within the anomaly most likely results from atmospheric processing of the Pt-rich material.

Materials with high Pt/Ir ratios and essentially no Al are known among magmatic iron meteorites (20, 21). Finding a terrestrial Pt-rich and Ir-, Al-poor source is difficult. Most volcanic rocks have elevated Pt/Ir ratios, although not as high as in iron meteorites, but Pt/Al ratios are very low (e.g., refs. 22, 23). Mantle rocks are depleted in Al, but have essentially unfractionated Pt and Ir (24). The only known terrestrial material with Pt/Ir ratios comparable to those in iron meteorites is the Pt-rich sulfides from the Sudbury Footwall (25). However, both terrestrial and extraterrestrial high-Pt sources have substantially lower Pt/Ir ratios than those at the top of the Pt peak, implying either Pt-Ir fractionation during atmospheric processing of the Pt-rich materials or multiple injections of materials with different Pt/Ir ratios not sampled so far.

Thus, the highly fractionated Pt/Ir ratio rules out mantle or chondritic sources of the Pt anomaly (Fig. 2). A further discrimination between Pt-rich crustal materials like Sudbury Footwall ore (25) and fractionated extraterrestrial sources such as Ir-poor iron meteorites like Sikhote-Alin (26) is difficult because of the comparable magnitude of the Pt/Ir fractionation in these materials. Circumstantial evidence hints at an extraterrestrial source of Pt, such as very high, superchondritic Pt/Al ratios at the Pt anomaly and its timing, which is clearly different from other major events recorded in the GISP2 ice core, including well-understood sulfate spikes caused by volcanic activity and the ammonium and nitrate spikes associated with biomass destruction (Fig. 1C).

Until the question about the nature of Pt-rich material and the means of its delivery to the ice is resolved, an extraterrestrial source of Pt appears likely. For example, the Pt anomaly could be explained by multiple impacts of an iron meteorite like Sikhote-Alin or Grant (21, 26); the former is a large crater-forming meteorite shower. Assuming a global anomaly, the 62.5-cm-thick ice layer with the average Pt concentration of 30 parts per trillion (ppt) (Fig. 1) would require an iron meteorite like Sikhote-Alin of ∼0.8 km in diameter to account for the Pt budget at the YDB. Because complete disintegration of such a large iron meteorite during its atmospheric passage seems unlikely, the event is expected to form a crater of a few kilometers in diameter. No such crater at YDB has been found so far.

The main conclusion of our study is the detection of an unusual event during the Bølling-Allerød–YD transition period that resulted in deposition of a large amount of Pt to the Greenland ice. The Pt anomaly precedes the ammonium and nitrate spike in the GISP2 ice core (2) by ∼30 y and, thus, this event is unlikely to have triggered the biomass burning and destruction thought to be responsible for ammonium increase in the atmosphere and the Greenland ice (11). Although the data do not allow an unambiguous identification of the Pt source, they clearly rule out a chondritic origin of Pt. One of the plausible sources of the Pt spike is a metal impactor with an unusual composition derived from a highly fractionated portion of a proto-planetary core.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation.

The 11 ice core pieces (∼2 cm × 3 cm × 1 m each) provided by the National Ice Core Laboratory were processed in our clean laboratory at room temperature. The ice “sticks” packed in plastic sleeves arrived partially broken into smaller pieces. Before sampling, each stick was carefully aligned in the original sleeve and then split into eight samples, each ∼12.5 cm long, using a metal bar wrapped first in aluminum foil and then in plastic wrap. Subsequently, each sample was extracted from the sleeve, carefully washed with ultrapure deionized (DI) water to remove possible surface contamination, and placed in a tall 300-mL polypropylene container, precleaned in 1:1 HCl and then 1:1 HNO3 for several days. Small ice fragments and water left in a sleeve were composited and used to develop and test analytical protocols. “Composites” from several sleeves were combined to get total weight comparable to that of the real ice samples. In total, 88 ice samples (samples 1–88 in Table S1), ranging from 38.42 g to 68.90 g, and 5 composite samples (samples 89–93 in Table S1) were collected and processed. The empty and filled polypropylene containers were weighed with a precision of ±0.01 g.

Ice samples were melted at room temperature in closed containers and the water was slowly evaporated at 80–90 °C on a hot plate down to 1–2 mL. The remaining samples were carefully transferred into precleaned (boiled in 1:1 HCl and then 1:1 HNO3) 6-mL, perfluoralkoxy (PFA) teflon beakers. Each polypropylene container was then washed at least twice with 1–2 mL ultrapure DI water, and the washes were collected and added to the corresponding PFA beakers.

Sample Dissolution.

We attempted to measure the total Ir and Pt concentrations in ice, including all solids cemented in ice. Consequently, we applied a multiple-step dissolution method as documented below.

The 93 samples along with 2 procedure blanks were (i) dried down on a hot plate, (ii) sealed with 1 mL of a 1:1 mixture of concentrated HF and concentrated HNO3 and heated at 150 °C in an oven for 1 wk, (iii) dried down again, (iv) redissolved in 0.4 mL of aqua regia (one part concentrated HNO3 and three parts concentrated HCl), and (v) finally diluted with 1 mL of ultrapure DI water to yield analytical solutions of ∼1.45 g each. Both empty and filled PFA beakers were weighed with a precision of ±0.0001 g.

The HF-HNO3 step is aimed at breaking down the silicates, and the aqua regia step is aimed at transferring all PGEs into solution because it is well known that Ir and Pt are not stable in diluted HNO3 (e.g., ref. 27). The latter has been confirmed by our tests using the composite samples. Our approach differs from previous studies such as refs. 28–30, in which ice samples were melted, preconcentrated by subboiling point evaporation, and added concentrated HNO3 to form 1% HNO3 analytical solutions for ICP-MS measurements. Such a treatment is unable to transfer all Ir and Pt into solution. Our approach is also different from that of ref. 31, which measured PGE concentrations only in particles in the size range 0.45–20 μm. This explains why our measurements yield much higher Ir and Pt concentrations in ice compared with those in refs. 28 and 31.

ICP-MS Measurements.

All ice samples, in diluted aqua regia matrix, were analyzed in two analytical sessions, using a GV Instruments Platform ICP-MS, first for Ir, Pt, Lu, and Hf with an Apex inlet system to increase sensitivity and reduce oxide interferences and then for major elements with a normal glass spray chamber. For Ir-Pt measurement, peaks of 175Lu, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180Hf, 191, 193Ir, and 194,195,196, 198Pt were monitored. Because of the special memory effects of Ir and Pt, diluted aqua regia (2.5 mL concentrated HCl + 7.5 mL concentrated HNO3 + 90 mL H2O) was used as a wash solution. Instrumental blank was also measured for such a solution. Oxide formation rates of LuO/Lu and HfO/Hf were determined for a 10 parts per billion (ppb) Lu-Hf standard solution prepared from HPS 1,000-ppm single-element standards before and after analytical sessions. During all measurements, LuO/Lu was <0.01 and HfO/Hf < 0.05. Ratios of LuO/Lu (<0.01) and HfO/Hf (<0.05), measured in a Lu-Hf solution together with ice samples, were used to correct for oxide interferences (175Lu16O, 177Hf16O, 178Hf16O, 179Hf16O, 180Hf16O) on 191,193Ir and 194,195,196Pt, respectively. The oxide corrections were typically <5 atomic %. After oxide interference correction, the measured Ir and Pt isotopic compositions of ice samples are within 3% of those measured on the Ir-Pt standard solution, showing that our Ir-Pt measurements were not affected by LuO and HfO interferences.

During our Ir-Pt measurements, the ICP-MS was tuned with a 10-ppb In solution, and this solution was analyzed every five samples to monitor the instrumental sensitivity drift, which was less than 10% during any of our analytical sessions. A 10-ppb Ir-Pt standard solution, prepared from HPS 1,000-ppm single-element standards, was analyzed at the end of an analytical session to convert measured signal into concentrations. This is specially designed because of the long memory effects of Ir. For Ir, concentrations obtained using 191Ir and 193Ir (after oxide corrections) are within 3%, and an average is used. For Pt, although peak 198Pt is free of oxide interference, it suffers isobaric interference from 198Hg. Consequently, we used only 194,195,196Pt peaks (after oxide corrections). Concentrations obtained using 194,195,196Pt peaks are within 3% of each other, and an average is used. All ice samples were analyzed at least twice in a random order, with the average values reported in Table S1.

For major element measurements (Al), a Basalt, Hawaiian Volcanic Observatory (BHVO)-1 standard solution was measured every five to six samples to monitor the instrumental sensitivity drift, which was less than 10% during any of our analytical sessions. This solution was also used for calibration. All ice samples were analyzed at least twice in random order, with the average values reported in Table S1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Wally Broecker for encouraging this study, Dr. Mark S. Twickler for providing the GISP2 ice samples, and Dr. Robert P. Ackert for inspiring discussions. We also thank H. J. Melosh and two anonymous reviewers for helpful reviews. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant AGS-1007367 (to S.B.J.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1303924110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Alley RB, et al. Abrupt increase in Greenland snow accumulation at the end of the Younger Dryas event. Nature. 1993;362:527–529. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayewski PA, et al. The atmosphere during the younger dryas. Science. 1993;261(5118):195–197. doi: 10.1126/science.261.5118.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayewski PA, et al. Changes in atmospheric circulation and ocean ice cover over the North Atlantic during the last 41,000 years. Science. 1994;263(5154):1747–1751. doi: 10.1126/science.263.5154.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broecker WS, et al. Putting the Younger Dryas cold event into context. Quat Sci Rev. 2010;29:1078–1081. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rooth C. Hydrology and ocean circulation. Prog Oceanogr. 1982;11(2):131–149. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broecker WS, et al. Routing of meltwater from the Laurentide Ice Sheet during the Younger Dryas cold episode. Nature. 1989;341:318–321. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broecker WS. Geology. Was the Younger Dryas triggered by a flood? Science. 2006;312(5777):1146–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.1123253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lowell TV, et al. Testing the Lake Agassiz meltwater trigger for the Younger Dryas. EOS Trans. 2005;86:365–373. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baales M, et al. Impact of the Late Glacial Eruption of the Laacher See Volcano, Central Rhineland, Germany. Quat Res. 2002;58:273–288. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svensson A. The missing tephra horizons in the Greenland ice cores. Quat Int. 2012;279/280:478. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Firestone RB, et al. Evidence for an extraterrestrial impact 12,900 years ago that contributed to the megafaunal extinctions and the Younger Dryas cooling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(41):16016–16021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706977104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerr RA. Mammoth-killer impact flunks out. Science. 2010;329(5996):1140–1141. doi: 10.1126/science.329.5996.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinter N, et al. The Younger Dryas impact hypothesis: A requiem. Earth Sci Rev. 2011;106:247–264. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunch TE, et al. Very high-temperature impact melt products as evidence for cosmic airbursts and impacts 12,900 years ago. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(28):E1903–E1912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204453109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Hoesel A, et al. Nanodiamonds and wildfire evidence in the Usselo horizon postdate the Allerod-Younger Dryas boundary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(20):7648–7653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120950109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pigati JS, et al. Accumulation of impact markers in desert wetlands and implications for the Younger Dryas impact hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(19):7208–7212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200296109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meese DA, et al. The Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2 depth-age scale: Methods and results. J Geophys Res. 1997;102:26411–26423. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stuiver M, Grootes PM. GISP2 oxygen isotope ratios. Quat Res. 2000;53:277–283. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zielinski GA, Mayewski PA, Meeker LD, Whitlow S, Twickler MS. A 110,000-yr record of explosive volcanism from the GISP2 (Greenland) ice core. Quat Res. 1996;45(2):109–118. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wasson JT. Trapped melt in IIIAB irons; solid/liquid elemental partitioning during the fractionation of the IIIAB magma. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1999;63:2875–2889. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wasson JT, Huber H, Malvin DJ. Formation of IIAB iron meteorites. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2007;71:760–781. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Day JMD. Hotspot volcanism and highly siderophile elements. Chem Geol. 2013;341:50–74. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Z, Mao J, Mahoney JJ, Wang F, Qu W. Platinum group elements in the Emeishan large igneous province, SW China: Implications for mantle sources. Geochem J. 2005;39:371–382. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maier WD, et al. The concentration of platinum-group elements and gold in southern African and Karelian kimberlite-hosted mantle xenoliths: Implications for the noble metal content of the Earth’s mantle. Chem Geol. 2012;302/303:119–135. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mungall JE, Naldrett AJ. Ore deposits of the platinum-group elements. Elements. 2008;4:253–258. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petaev MI, Jacobsen SB. Differentiation of metal-rich meteoritic parent bodies: I. Measurements of PGEs, Re, Mo, W, and Au in meteoritic Fe-Ni metal. Meteorit Planet Sci. 2004;39:1685–1697. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenwood NN, Earnshaw A. Chemistry of the Elements. Oxford: Pergamon; 1985. pp. 1–1542. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabrielli P, et al. Meteoric smoke fallout over the Holocene epoch revealed by iridium and platinum in Greenland ice. Nature. 2004;432(7020):1011–1014. doi: 10.1038/nature03137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gabrielli P, et al. A climatic control on the accretion of meteoric and superchondritic iridium-platinum to the Antarctic ice cap. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2006;250:459–469. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soyol-Erdene TO, Huh Y, Hong S, Hur SD. A 50-year record of platinum, iridium, and rhodium in Antarctic snow: Volcanic and anthropogenic sources. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45(14):5929–5935. doi: 10.1021/es2005732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karner DB, et al. Extraterrestrial accretion from the GISP2 ice core. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2003;67:751–763. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.