Abstract

Background

Computing technology has the potential to improve health care management but is often underutilized. Handheld computers are versatile and relatively inexpensive, bringing the benefits of computers to the bedside. We evaluated the role of this technology for managing patient data and accessing medical reference information, in an academic intensive-care unit (ICU).

Methods

Palm III series handheld devices were given to the ICU team, each installed with medical reference information, schedules, and contact numbers. Users underwent a 1-hour training session introducing the hardware and software. Various patient data management applications were assessed during the study period. Qualitative assessment of the benefits, drawbacks, and suggestions was performed by an independent company, using focus groups. An objective comparison between a paper and electronic handheld textbook was achieved using clinical scenario tests.

Results

During the 6-month study period, the 20 physicians and 6 paramedical staff who used the handheld devices found them convenient and functional but suggested more comprehensive training and improved search facilities. Comparison of the handheld computer with the conventional paper text revealed equivalence. Access to computerized patient information improved communication, particularly with regard to long-stay patients, but changes to the software and the process were suggested.

Conclusions

The introduction of this technology was well received despite differences in users' familiarity with the devices. Handheld computers have potential in the ICU, but systems need to be developed specifically for the critical-care environment.

Keywords: computer communication networks, medical informatics, medical technology, microcomputers, point-of-care technology

Introduction

The rapid development of computing technology has had a major impact on health care, particularly in technology-oriented areas such as critical care. Electronic patient records require a major commitment by the institution, in hardware, software, training, and support. In many places, bedside care of patients still relies on paper records or nonintegrated computer systems that do not take full advantage of their data-management capabilities [1]. Even where there are advanced computerized systems, the bedside clinician may still rely on written notes for patient management and billing, and refer to pocket textbooks or printed management algorithms.

For busy clinicians, the use of computers for hospital-based clinical care may be hampered by the computers' inaccessibility. Handheld computing technology is versatile and relatively inexpensive [2], combining many of the benefits of electronic patient records and paper charts. Handheld computers have been described in various medical situations; early reports describe programmable calculators used to make complex calculations in intensive-care units (ICUs) [3]. Handheld devices are increasingly being used by physicians for a variety of functions, such as scheduling, accessing drug reference information, patient data storage and billing. However, there are few published reports describing the benefits of this technology [4, 5, 6, 7].

In view of the potential advantages and increasing use of handheld computers in medicine, we evaluated the benefits and drawbacks associated with introducing this technology in an academic ICU.

Materials and methods

Hardware

The Palm III series handheld device (Palm device, Palm Canada Inc, Toronto, Ontario) was used, as some of our staff were familiar with this equipment. It is a pocket-sized (8 × 12 cm; 165 g) computer with a 4-Mb (PalmIIIx) or 8-Mb (PalmIIIxe) memory. It has an infrared data association (IrDA) port that allows transmission of data between Palm devices and other IrDA-compatible devices such as printers, laptop computers and cellphones. The device has a monochrome 160 × 160 pixel liquid-crystal display screen (Fig. 1) and allows the user to input data either by writing on the touch-sensitive screen with a stylus or by tapping on an on-screen keyboard. Handwriting is deciphered by Graffiti handwriting-recognition software (Palm Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA), which requires the user to learn specific characters. For users who preferred to enter data using a keyboard, two GoType keyboards (LandWare Inc, Oradell, NJ, USA) were found in the ICU. When the Palm device was placed in this keyboard, the user could type in the standard way.

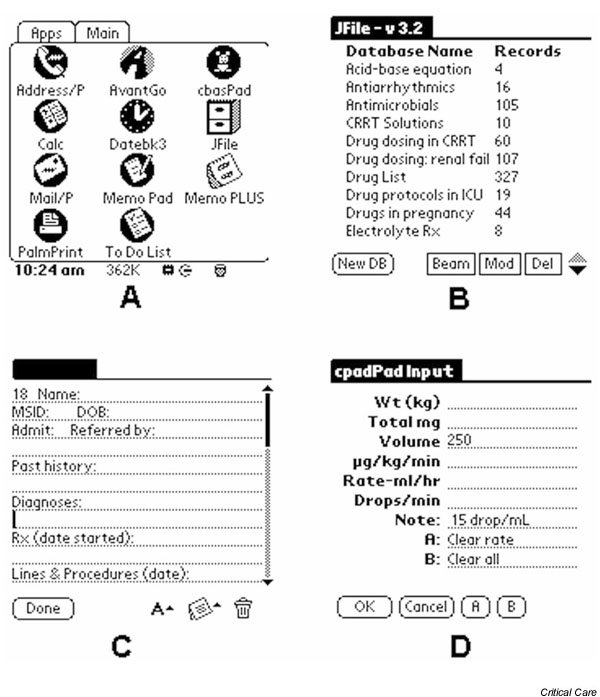

Figure 1.

Palm device screens: examples of screen layout for various software applications as installed for this study. (A) The main screen; (B) the J-file database menu; (C) the patient data template; (D) CbasPad intravenous infusion calculator.

Software

Each personal digital assistant (PDA) was installed with medical reference information as well as hospital and ICU specific guidelines (Table 1). This occupied approximately 2 Mb of memory. The applications that come with the PDA (Addressbook, Datebook, Memopad, To Do list) were used for essential telephone numbers as well as call and teaching schedules, but additional software was required for medical databases. The spreadsheet database program JFile (Land-J Technologies, Orlando, FL, USA) was used for reference information, such as drug doses and laboratory reference ranges. The text readers AvantGo (AvantGo Inc, San Mateo, CA, USA) and iSilo (www.isilo.com), which convert word-processing and HTML documents, were used for textual medical reference information. CbasPad, a Tiny BASIC programming language interpreter and editor, was used to develop software to perform common critical-care calculations, such as calculated creatinine clearance and intravenous infusion rates. Additional software for medical reference data was introduced during the study period, including ePocrates qRx [8], a drug information database.

Table 1.

Software applications and examples of the databases provided on Palm handheld computers

| Application | Database/information |

| Addressbook* | Hospital and staff telephone numbers |

| Emergency numbers | |

| Datebook* | Call schedules |

| Schedules for teaching and rounds | |

| Memopad* | Patient database |

| To Do list* | |

| Calculator* | |

| J-file | Acid-base equations |

| Dialysis solutions | |

| Vasopressor protocols | |

| Electrolyte replacement | |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | |

| Normal laboratory values | |

| Drug dosing in renal failure | |

| Drugs in pregnancy | |

| AvantGo | ICU orientation manual |

| Antimicrobial therapy | |

| Research study summaries | |

| Ventilator weaning protocol | |

| Organ-donation criteria | |

| Residents' objectives | |

| Cbas Pad | Calculators of |

| Creatinine clearance | |

| Ideal body weight | |

| Respiratory parameters | |

| Fractional excretion sodium | |

| Harris-Benedict equation | |

| Intravenous drug rate | |

| PalmPrint | Printout of daily note |

* Basic applications standard with the Palm handheld device.

Patient data were entered into the Memopad using a customized template generated with MemoPlus (Hands High Software Inc, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The information entered included demographic data, medical history, current diagnoses, therapy, procedures performed, and management plan. Data was transferred between medical personnel using the PDA's infrared beaming ability. As hospital policy requires a paper record, daily notes were generated by Palmprint software (Stevens Creek Software, Cupertino, CA, USA) using infrared transmission to an HP Laserjet 6P printer (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Various software packages for patient data management (shareware or commercially available software) were evaluated during the study period.

In the light of focus-group feedback, a more comprehensive reference database was developed. The electronic files for the Critical Care Handbook of the Massachusetts General Hospital [9] were provided by the publishers, and converted to a PDA-readable (iSilo) format. This 1.4-Mb file contained the full text of the book, with multiple hyperlinks, and some of the images. Hard copies of the book were also obtained.

Study subjects

PDAs were given to the ICU attending physicians, the rotating resident trainees, and other medical staff. Four to six residents (postgraduate years 2 to 4) worked in the ICU at any one time. On the first day of their ICU rotation, residents were taught how to use the PDA in a 1-hour seminar. The principle investigator and research team were available for further help and troubleshooting throughout the study The research team was responsible for installing and updating software and schedules. Patient data was entered by residents, either during morning rounds or when patients were admitted to the ICU. The updated database was beamed to the on-call resident in the evening and transmitted back to the team in the morning, with new admissions added.

Methodology

An independent evaluation company (Smaller World Communications, Richmond Hill, Ontario) with experience in focus-group methodology was contracted to develop the qualitative methodology, collect data through focus-group meetings, and analyze the data [10, 11]. A preliminary moderator's guide was developed and tested on an expert panel, comprising two critical care physicians, an anaesthesiologist, three medical residents with experience in data management or PDAs, and a representative from Palm Canada Inc. The moderator's guide was designed to stimulate discussion about users' familiarity with the technology, the benefits to patient management, and the drawbacks encountered. Finally, ideas were generated for new applications for the technology and improvements to the hardware and software. Three focus groups were held with the residents and staff who used PDAs in the ICU. Tapes were transcribed verbatim and the notes were analyzed for themes by a research analyst [12]. Interim reports from the meetings were provided to the investigators. On the basis of this feedback, ongoing improvements were made to the medical databases and patient-management software.

The PDA reference database was evaluated objectively using a crossover study. The trainees' rotation was split into two 3-week periods. One of the periods was allocated as a control (PDA-free) block and in the other the PDA was available. Two groups of trainees were studied: in one the PDA period preceded the PDA-free period, and in the other, the order was reversed. During the PDA period, trainees had access to the full PDA database as well as the electronic version of the Critical Care Handbook of the Massachusetts General Hospital [9]. The printed copy of the handbook was given to trainees during the PDA-free period.

Objective evaluation was accomplished using a pair of standardized clinical scenario tests made up of 20 questions answered over 30 minutes. The questions were about common critical-care problems, drawn randomly from a pool of questions written by physicians in our ICU and at other teaching hospitals in the Toronto area. Trainees made use of the textbook (control period) or PDA database (study period) during the examination. To standardize for the possible difference in difficulty between the two tests, 11 General Internal Medicine trainees, not involved in the PDA study, wrote both the tests. This generated a mean and standard deviation for each test. Study trainees' results were expressed as the standard deviation above or below this control mean, and compared using a permutation test, with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

During the 6-month study period, PDAs were used by 20 physicians (4 attending physicians, 1 research fellow, and 15 rotating medical residents) and 6 paramedical staff (3 respiratory therapists, 2 pharmacists, and 1 nurse educator). The three focus groups had a total of 19 participants. Two residents who were unable to attend participated in telephone interviews. Each focus group had six or seven participants, a number within the recommended range [11]. Only five of the users (19%) had previous experience with the PDA computing format.

Physical attributes

Users found the PDA to be a convenient pocket size, allowing it to be available at all times. The screen was clear and easy to read, although not ideal for long text documents or large tables. Many users became proficient in text entry using Graffiti, while others preferred to use the GoType keyboards. Of the 19 PDA units used during the 6-month study period, only one had a technical malfunction requiring replacement. Two were damaged after being dropped and needed to have their screens replaced. No other problems were encountered.

Medical reference databases

Reference databases used regularly by medical residents included the critical-care drug dosing reference, ventilator weaning protocol, and electrolyte correction application. The calculation programs (creatinine clearance, ideal body weight) were found to be useful by the pharmacist and some residents. The ventilator weaning protocol was used by medical staff, as well as respiratory therapists, allowing regular assessment of whether patients met the criteria for extubation.

Many databases were, however, not fully used. This appeared to relate more to inadequate training than to faults in the databases. In many cases, the PDA users were unaware that certain information was in their PDAs. This was because data were located on separate software programs (J-file, AvantGo, Cbas, Memopad) and may have been difficult to find. The PDA had a global 'Find' function to search for keywords, but this does not incorporate some of the added software programs, such as AvantGo. A unified database program with a search capability was suggested as a useful addition.

Patient-management software

Patient information was managed using the text-based MemoPlus software and a customized template. This required text entry on the PDA. Several modifications to the template were made during the study period. Residents responsible for patient data entry described difficulty entering data for new patients and keeping patient information updated during busy weekends. Attending staff found the patient data useful, particularly when they were taking over care of patients at the beginning of their on-call duties. Transferring the care of critically ill patients to a new physician is time-consuming and potentially stressful. The PDA patient database improved the staff's knowledge of patients, especially of previous medical problems in patients with complex conditions who had had a long stay in hospital. It also gave staff access to patient information when they were out of the ICU, aiding decision-making. During ICU rounds, the summarized chronological information was useful to find out how long intravenous lines had been in place and to review antibiotic therapy. Less benefit was noted in short-term patients. During night call, the patient summaries were of value when residents were called to see patients with whom they were not very familiar.

In our ICU, a daily physician note is written in the patient record. The print function to create a daily note reduced duplication of work, but the process for entering patient data was found to be time-consuming initially. While residents did not feel that the patient-management application (MemoPlus) improved efficiency, it did increase their knowledge of the patients.

During the study period, other commercially available patient-management software systems were evaluated. These had the advantage of easy data input using single keystrokes for date entry and 'pop-up' lists of drugs and diagnoses. While this simplified data inputting, no system was found to be ideal for the ICU. Many of these systems did not support the infrared data transfer or printing functions.

Other uses of the software

Study participants used a variety of other applications on a regular basis. Having the call and teaching schedules easily accessible was considered a benefit. The telephone list of hospital numbers was found to be valuable and the To Do list was used by most users to keep track of their work. Teaching rounds and morbidity and mortality rounds were facilitated by using archived patient data. Many participants used the Memopad to take notes in teaching seminars.

Suggestions for change

The focus-group discussions generated a number of suggestions for improvement. The hardware unit was considered suitable, but a more robust one may be needed in view of the two damaged screens. Because most of the users had had no previous experience with the PDA, additional teaching sessions and follow-up training were suggested to make optimal use of the technology. This would have helped users to become more aware of the many databases available on their PDA. In this regard, the medical information on the PDA would clearly benefit from integration into a single, searchable program.

The patient-management software would be more user-friendly if the data could be entered with minimal effort, using customized pull-down lists of drugs, diagnoses, and procedures. The demographic data could be entered and updated daily by a ward clerk. Alarms were suggested - for example, to warn of prolonged intravenous line duration or the end of a course of antibiotic therapy. While transmission of data between staff by infrared was found to be useful, synchronization with the hospital electronic patient record was considered the optimal situation.

Objective evaluation

Two groups of four trainees took part in each crossover study. Half of the residents had prior experience with PDAs. No difference was noted in their subjective preference for the PDA or printed copy of the handbook, and the individual's preference did not correlate with previous PDA experience. Comparison of the test scores revealed no difference between the scores in the PDA-assisted test and the paper-assisted test, analyzed after correction for difficulty using the control mean and standard deviation.

Discussion

This study prospectively evaluated the benefits and drawbacks associated with the introduction of handheld computers in an academic-critical care environment.

Who benefitted most?

The introduction of handheld computers was well received by all users, despite differences in their familiarity with these devices. The most favourable response was from the more senior staff, namely, the attending physicians and fellows. This may be because of the longer time they were involved in the study, allowing more familiarity with the PDA platform. They were also more likely to benefit from having patient data available while on call outside the ICU. Furthermore, they were usually not responsible for entering patient data. Clearly, two conditions that might enhance the acceptance of these technological changes are adequate education and ease of data entry. Although an initial education session was held, it was when the junior medical staff in the study were beginning their rotation in an unfamiliar environment.

Making the devices more user-friendly

The patient data applications assessed were not ideal but did enable us to identify several criteria for a user-friendly system. These include ease of data entry using shortcuts and lists, limiting the range of data stored to that essential for patient management, and the ability to transmit data easily between staff. It is important that this computerized patient database should decrease workload and not cause duplication in work. In our study, enabling residents to print a daily note from their handheld computer offset the additional work of data entry. Ideally, the handheld system should be integrated with the hospital electronic patient record, allowing direct entry of demographic data as well as access to laboratory data.

A wireless capability may also have significant benefits with respect to medical information databases. This would allow access to Medline searches and evidence-based guidelines. While internet access is available from desktop computers in the ICU, the ability to perform these searches on rounds or while consulting outside the ICU may be beneficial.

Databases on paper or on screen?

The comparison of paper and electronic databases did not reveal an advantage of one medium over the other. No significance difference was observed between the objective scenario test scores using the PDA or the paper database. The fact that equivalent results were obtained using this single database may suggest a potential benefit of using the PDA. The memory capability of the 8-Mb device would allow the trainees to carry five reference texts each of a size similar to that of the Critical Care Handbook of the Massachusetts General Hospital.

What is needed

Critical-care decision-making requires rapid access to strategic clinical data as well as to medical reference information. A patient in an ICU generates a large amount of data, and the number of information variables may exceed what clinicians can integrate and process [13]. Current information technology has the potential to realize the needs of the intensivist, but no customized product has been developed for this use. Handheld technology has a definite role to play, but systems need to be developed specifically for the critical-care environment to optimize real-time patient data management and communication between health care workers.

Abbreviations

HTML = hypertext markup language; ICU = intensive-care unit; IrDA = infrared data association; Mb = megabytes; PDA = personal digital assistant.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by Palm Canada Inc. Jason Weshler received an Ontario Thoracic Society summer student scholarship. We thank Lippincott Williams & Wilkins and Dr WE Hurford for providing the electronic files for the Critical Care Handbook of the Massachusetts General Hospital.

References

- Sado AS. Electronic medical record in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 1999;15:499–522. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebell M, Rovner D. Information in the Palm of your hand. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:243–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FH, Davies RS. The handheld computer in critical care medicine. Am Surg. 1986;52:452–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong BC, Doyle DJ. Respiratory consultant: a hand-held computer-based system for oxygen therapy and critical care medicine. Int J Clin Monit Comput. 1997;14:155–163. doi: 10.1007/BF03356590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helwig AL, Flynn C. Using palm-top computers to improve students' evidence-based decision making. Acad Med. 1998;73:603–604. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199805000-00075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnard P. Data collection using a palm-top computer. Prof Nurse. 1995;11:35–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal M, Wolford RW. Resident procedure and resuscitation tracking using a palm computer. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ePocrates qRx www.epocrates.com

- Hurford WC. Critical Care Handbook of the Massachusetts General Hospital, 3rd edn Boston: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000.

- Kreuger RA. Developing questions for focus groups: Focus Group Kit 3. In The Focus Group Kit London: Sage Publications, 1998.

- Kreuger RA. Moderating focus groups: Focus Group Kit 4. In The Focus Group Kit London: Sage Publications, 1998.

- Kreuger RA. Analyzing and reporting focus group results: Focus Group Kit 6. The Focus Group. London: Sage Publications, 1998.

- Morris AH. Computerized protocols and bedside decision support. Crit Care Clin. 1999;15:523–545. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]