Abstract

Little is known about the role of trauma and PTSD symptoms in the context of migration-associated HIV risk behaviors. A survey of Tajik married male seasonal labor migrants in Moscow was completed by 200 workers from 4 bazaars and 200 workers from 18 construction sites as part of a mixed method (quantitative and qualitative) study. The mean PC-PTSD score was 1.2 with one-quarter of migrants scoring at or above the cutoff of 3 indicating likely PTSD diagnosis. PC-PTSD score was directly correlated with both direct and indirect trauma exposure, but PC-PTSD score did not predict either HIV sexual risk behaviors or HIV protective behaviors. HIV sexual risk behavior was associated with higher indirect trauma exposure. PC-PTSD score was associated with some indicators of increased caution (e.g. more talking with partners about HIV and condoms; more use of condom when drinking). Qualitative findings were used to illustrate the differences between direct and indirect traumas in terms of HIV sexual risk. The study findings call for future efforts to address labor migrant's mental health needs and to integrate trauma dimensions into HIV prevention.

Keywords: trauma, PTSD, HIV risk, labor migrants

Introduction

Labor migration has become a focus of attention as a contributor to the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. Evidence from several different geographic regions suggests that migrant workers are at higher risk of contracting HIV/AIDS (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). Public health officials are concerned that migrant workers may serve as a “bridge”-- transmitting HIV/AIDS to the general populations in both the sending and receiving countries (7).

No known studies have rigorously examined the relationship between trauma and PTSD symptoms as possible determinants of HIV risk and preventive behaviors among labor migrants. Several studies have reported trauma exposure among immigrants (8, 9). One qualitative study of emigrants from sub-Saharan Africa who were residing in Sweden noted that a history of pre-migration trauma could be associated with HIV-risk behavior (10).

HIV/AIDS and Labor Migrants from Tajikistan

Central Asia and Eastern Europe report the fastest rates of HIV/AIDS growth in the world (11). Massive political, social, cultural and behavioral changes, along with economic upheaval and the collapse of the public health infrastructure, have created circumstances conducive to the rapid spread of HIV/AIDS (12). These circumstances characterize the situation that currently exists in Tajikistan.

Tajikistan, a former Soviet republic, has a highly mobile population. In the aftermath of the civil war (1992 to 1997), Tajikistan was transformed from a state of internally displaced persons and refugees to one of the largest regional labor exporters (13). Over one million Tajik citizens now work outside of their country. Most migrants are male (80%), married (70%), and between 30 and 40 years of age (14).

The primary destination for Tajik labor migrants is Russia. Because of its rapid economic growth, Russia needs laborers for the most difficult, dirty, and dangerous work, the so-called “3D” jobs. The majority of Tajik migrants live and work in Moscow, carrying goods in the bazaars and working in construction sites. Far from their families, most Tajik male migrants have sex with multiple partners, including Moscow-based sex workers, who are known to have rates of HIV-1 that are 30 to 120 times higher than that of Moscow's general population (15).

Presently Tajikistan is classified as a HIV/AIDS low prevalence country (11). In May 2011 there were 3051 registered HIV positive cases in Tajikistan, though it is suspected that cases are still going undetected (16). Public health officials are concerned about the potential for a rise in HIV/AIDS rates given especially the risks posed by migration. Prior ethnographic studies of Tajik labor migrants documented several findings that suggested trauma could also be an issue. One prior study comparing internal and external labor migrants found that external migrants reported far more difficulties with harsh living and working conditions (17). Another study of labor migrants to Moscow described the sense of being “unprotected,” or being subjected to difficult conditions, unfair treatment, beatings, without legal rights or health care access (18). These findings called for further research examining more closely trauma exposure and traumatic stress through a survey of male migrants from Tajikistan to Moscow, which is the focus of this report.

Trauma and HIV Risk Behaviors

Different forms of trauma have been considered as possible determinants of HIV risk behavior in several other populations. Childhood abuse, physical abuse, and especially sexual abuse have been found to be associated with unprotected sex and an increase in STI and HIV infection rates in several different populations: university students (19), among men who have sex with men (20), in people living with HIV (21), among individuals with a mental illness and/or substance abuse (22, 23, 24, 25) in African American women (26), urban American Indian women (27), women in substance abuse treatment (28), and women prisoners (29).

Various hypotheses have been considered to explain the relationship between trauma and HIV risk. Several studies have investigated the possible associations between trauma, alcohol and drug use, and HIV risk behaviors. Catania and colleagues (30) found that the effect of childhood sexual coercion on sexual risk was mediated by substance use, patterns of sexual contacts, and partner violence, but not by adult sexual revictimization or depression. Simoni et al found that injecting drug use mediated the relationship between non-partner sexual trauma and high-risk sexual behaviors (27). They interpreted their findings to mean that, “nonpartner sexual trauma was associated with IDU, which, in turn, accounted for a significant part of the relationship between non-partner sexual trauma and high-risk sex”(p. 42). Others have noted the roles of: stimulus seeking behavior in prompting risky sexual behavior; depression in driving a need for affiliation; and substance abuse in impairing judgment (31, 32).

Understanding the Possible Associations Between Labor Migration, Trauma, and HIV Risk and Protective Behaviors

This research, guided by gender schema theory (33) and migration theory (34), posits that labor migration transforms male migrants' experience of masculinity, both heightening exposure to and participation in HIV risk scenarios and raising new possibilities for prevention. This framework is focused on understanding the relationship between contextual factors, masculine norms and schemas, and HIV risk and preventive behaviors. For example, it led us to hypothesize that as a consequence of their exposure to adversity and trauma, men's status is weakened or men perceive their status as weakened; this weakened status may lead either to lower perceived self-efficacy and reduced HIV protective behaviors, or to increased sexual risk taking. It also led us to ask whether particular forms of trauma (such as direct or indirect) would be more associated with these changes.

The central research questions addressed in this study were: 1) What is the prevalence of trauma exposure, indicators of traumatic stress symptoms, and likely PTSD diagnosis among Tajik male labor migrants in Moscow? 2) What, if any, are the associations between trauma exposure, indicators of traumatic stress symptoms, and HIV risk and protective behaviors? How do the qualitative findings further explain any such associations? 3) What are the implications of these associations, if present, for HIV and mental health prevention practice, policy, and research with labor migrants?

Methods

Approach to Sampling

Tajik male migrant workers from Moscow were sampled from bazaars and construction sites, which serve as the largest base of employment for Tajik migrants in Moscow. For the first stage of each, sample size measures of the number of workers in each bazaar and the number of workers at each construction site were obtained from the Union of Tajik Migrants. The estimated population sizes for the two samples were as follows. There were 40 bazaars, with a total of 17,324 workers across all of them. There were 102 construction sites, with 7,336 workers across them all. Each bazaar and construction site is further divided into multiple brigades of workers.

Sampling was conducted in three stages: sampling bazaars, sampling brigades within the bazaars, and sampling workers within the brigades. In the first stage, bazaars were sampled with probabilities proportionate to size (PPS), where the measure of size was the number of workers. In the second stage, because brigade size within bazaar varied little, brigades were sampled with simple random sampling. In the last stage, we sampled 10 workers from each brigade with simple random sampling. The sampling interval for the bazaars was 3464 (N/number of clusters). For the brigades the probability of selection was 4/# of brigades in the bazaar. The denominator of this fraction ranged from 3 to 140. In the bazaar with only 3 brigades, we sampled all three. In the bazaar that was sampled twice, the probability of selection of brigades was 8/140. For sampling workers in the brigades, the probability of selection was 10 divided by the brigade size. Simple random sampling (SRS) was implemented at the subsequent stages as follows. We assigned random numbers to the lists of workers to determine which ones should be sampled. The random sample of brigades from each bazaar was also done by assigning random numbers to the list of bazaars within each sampled brigade.

The sampling of construction sites was a two-step process. In the first step, we sampled 20 construction sites from a total of 500, with PPS, where the measure of size was again the number of workers. In the second stage, we drew a simple random sample of 10 workers from each of the 20 sites, for a total of 200 workers. The PPS procedure for the construction sites was the same as that for sampling bazaars. The process for sampling workers from each site was the same as the process for sampling workers from brigades. For the construction sites, the sampling interval for the sites was 367 (N/number of clusters). The probability of selection of workers was 10 divided by the number of workers at each site. The denominator ranged from 25 to 1000, but the site with 1000 workers was sampled 3 times, so that sampling fraction was 30/1000. The SRS process for construction workers was the same as described above for bazaars.

Measures

We constructed a survey instrument that combined items and scales from existing instruments that have been used with migrants with new items and scales focused on key issues concerning masculinity and migration. The survey consisted of items with either forced choice (yes/no or Likert scale) responses or numerical response (e.g. estimate the percentage). It was designed to be self-administered in one hour or less in order to be easily completed by the migrants. Questionnaires were translated into Russian, as all Tajik migrants are literate in Russian. The survey consisted of questions in the following realms

Demographic characteristics

Items addressing age, educational level, family, work, finances, and religion, were adapted from the CAFES and CHAMP surveys (35, 36).

Marriage and sexual partners

Items addressing the wife in Tajikistan and regular partner in Moscow, sexual risk behaviors, HIV testing, and condom use, were adapted from the AIDS survey and CHAMP survey (36, 37, 38).

HIV/AIDS

HIV/AIDS knowledge was assessed via 18 items, worry about AIDS with 4 items, and talking with persons about AIDS with 7 items. These questionnaires were adapted from the HIV knowledge survey and CHAMP survey with alpha coefficients ranging from .74 to .87 in this study (36, 37).

Health & access

Health was assessed with the SF-12 (39). Cronbach's alpha was .70 for the sample. Access was assessed via a scale of 5 items addressing health services access that was adapted from the CAFES surveys (35). Other items asked about alcohol and drug use.

Trauma Exposure

To maximize the relevance of the instrument to the social context of Tajik migrants in Russia, the Traumatic Events Inventory was designed by the researchers specifically for Tajik labor migrants. The instrument, which utilized existing instruments for assessing traumatic events associated with torture and refugees as its foundation (40, 41), contains 18 items. The respondent indicates whether or not he experienced the event (direct trauma), or heard about others experiencing it (indirect trauma). For example, one item asks respondents to indicate whether they have experienced the murder of a family member or friend or have heard of anyone else experiencing the murder of a family member or friend. A cumulative score was calculated. Cronbach's alpha scores were .81 (direct trauma) and .91 (indirect trauma) for the sample. Regarding sexual trauma, a small number of migrants answered yes to this question. We debriefed all of them and learned that each had misinterpreted the item so their responses were recoded.

PTSD Screening Instrument

The PC-PTSD Screen is a 4-item self-administered screen for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) that has been found to have good test–retest reliability (r = .80) and yielded a sensitivity of .91 and specificity of .80 using a cut score of 3 (42). It consists of 4 items, that correspond to the different PTSD symptom clusters: 1) Reexperiencing: nightmares or having thought about it (traumatic event(s)) when you didn't want to; 2) Avoidance: having tried hard not to think about it; 3) Hyperarousal: being alert, careful, frightened; 4) Numbness: felt numb or detached from others, activities, surroundings. Among Tajik labor migrants, the Cronbach's alpha was .90.

Careful attention was paid to cross-cultural preparation of the measures. The research team includes several professionals from both Tajikistan and Russia who assisted with the translation of the instruments and assessed the extent to which the translations succeeded. Each research team member carefully reviewed the instrument. Issues or disagreements were resolved by consensus. Think-a-loud interviews (both concurrent and retrospective) with migrants were used to ascertain what respondents thought questions meant and how they formulated their answers. The survey was piloted with 40 migrants. Item frequencies and scale reliabilities from the pilot data were compared to data collected from existing data sets. Items that did not fit the expected response patterns or that were difficult to answer were reassessed for cultural adaptability and then reworked.

Procedures

Trilingual (Russian, Tajik, and English), trained interviewers described the study to prospective participants in either Tajik or Russian depending upon the preference of the respondent, answered their questions, and then invited them to participate. Oral informed consent to participate was obtained as approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Illinois at Chicago, Case Western Reserve University, the Ministry of Health of Tajikistan, and the Russian Academy of Arts and Sciences. Those persons who gave oral consent were asked to complete the survey. Participants were each paid $20 for their participation in the survey. Surveys were self-administered survey in a private place (e.g. an office in the bazaar or the construction site), in the presence of a study fieldworker who offered to clarify any questions. Surveys were administered beginning in June 2009 and completed within two months.

Analytic Approach

To address research question one we first computed descriptive statistics and correlations (Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4). Given the survey sample design, this included comparing participants from PTSD and non-PTSD subgroups using regression analysis with generalized least squares method for continuous measures and Rao-Scott adjusted chi-square tests for discrete measures (Table 4). Tests of significance were conducted with adjusted F statistics. SAS software was used for the analysis (43).

Table 1. Types of Trauma Exposure.

| Trauma Exposure Item #s | Direct | Indirect |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of food or water | 58 (14%) | 241 (60%) |

| Ill health without access to medical care | 76 (19%) | 266 (66%) |

| Lack of shelter | 58 (14%) | 253 (53%) |

| Imprisonment | 10 (2%) | 270 (68%) |

| Serious injury | 33 (8%) | 259 (65%) |

| Being close to death | 9 (2%) | 199 (25%) |

| Sexual assault or rape | 0 (0%) | 0(0%) |

| Forced separation from family members | 13 (3%) | 52 (13%) |

| Murder of family or friends | 49 (12%) | 211 (53%) |

| Unnatural death of family or friends | 20 (5%) | 63 (16%) |

| Combat in the civil war | 14 (3%) | 120 (30%) |

| Losing loved ones in the war | 54 (13%) | 153 (38%) |

| Torture | 12 (3%) | 68 (17%) |

| Workplace accident | 53 (13%) | 260 (65%) |

| Beaten by police | 179 (45%) | 296 (74%) |

| Beaten by nationalists | 69 (17%) | 322 (80%) |

Table 2. Quantity of Trauma Exposure.

| Trauma Exposure (# of items endorsed) |

Direct Exposure |

Indirect Exposure |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 163 (41%) | 50 (12%) |

| 1 | 81 (20%) | 15 (4%) |

| 2 | 57 (14%) | 20 (5%) |

| 3 | 27 (7%) | 10 (2%) |

| 4 | 19 (5%) | 19 (5%) |

| 5 | 15 (4%) | 15 (4%) |

| 6 | 13 (3%) | 26 (6%) |

| 7 | 8 (2%) | 20 (5%) |

| 8 | 7 (2%) | 29 (7%) |

| 9 | 3 (1%) | 50 (12%) |

| 10 | 3 (1%) | 38 (9%) |

| 11 | 3 (1%) | 43 (11%) |

| 12 | 0 (0%) | 20 (5%) |

| 13 | 0 (0%) | 20 (5%) |

| 14 | 0 (0%) | 9 (2%) |

| 15 | 0 (0%) | 16 (4%) |

Table 3. Correlation matrix for independent and dependent variables.

| TD | TI | PTSD | VS | SW | CSW | CRP | Risk | Protect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD | 1.00 | ||||||||

| TI | .34*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| PTSD | .47 *** | .29*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| VS | .14*** | .27*** | .07 | 1.00 | |||||

| SW | .05 | .06 | .15*** | .22*** | 1.00 | ||||

| CSW | −.11** | −.04 | −.01 | .04 | −.09* | 1.00 | |||

| CRP | .09 | −.022 | .09* | −.01 | .12** | −.07 | 1.00 | ||

| Risk | .13** | .21*** | .16*** | .86*** | .68*** | −.02 | .09 | 1.00 | |

| Protect | .03 | .01 | −.04 | −.02 | .−.02 | −.67*** | −.69*** | −.02 | 1.00 |

.1 < p

p < .05

p < .005

TD: Direct trauma exposure

TI: Indirect trauma exposure

PTSD: PC-PTSD total

VS: Vaginal sex past month

SW: Sex workers past month

CSW: Use condom with sex worker

CRP: Use condom with regular partner

Risk: Weighted total of VS and SW

Protect: Weighted total of CSW and CRP

Table 4. Comparing Full Sample, PC-PTSD Negatives, and PC-PTSD Positives.

| Full Sample (n=400) | PC-PTSD neg. (n=293) | PC-PTSD pos. (n=107) | Test Statistic (F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 31.5(6.1) | 32.0 (0.52) | 30.2 (0.68) | 4.95*** |

|

| ||||

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 25(6%) | 13(4%) | 12(11%) | 10.04** |

| Secondary | 288(72%) | 219(76%) | 69(65%) | |

| College | 38 (9%) | 24(8%) | 14(13%) | |

| University (some) | 10(2%) | 9(3%) | 1(1%) | |

| University (degree) | 39(10%) | 28(9%) | 11(10%) | |

|

| ||||

| Region | ||||

| Dushanbe | 63(16%) | 30(10%) | 33(31%) | 8.62*** |

| Khatlon | 114 (29%) | 76(28%) | 38(36%) | |

| Sughd | 89 (22%) | 81(25%) | 8(5%) | |

| GBAO | 41 (100%) | 32(12%) | 9(10%) | |

| Subordinate | 92(23%) | 73(25%) | 19(18%) | |

|

| ||||

| Religion | ||||

| Sunni | 353 (87%) | 254(85%) | 99(92%) | |

| Ismaili | 47(13%) | 39(15%) | 8(8%) | |

|

| ||||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married (Taj) | 400(100%) | 221(100%) | 174(100%) | |

| Married (Rus) | 23(6%) | 14(7%) | 9(8%) | |

| Regpart (Rus) | 352(90%) | 255(88%) | 97(94%) | |

|

| ||||

| Migration | ||||

| # times in Russia | 4.3 (2.7) | 4.6 (.54) | 4.0 (.17) | |

| Work bazaar | 200(50%) | 117(39%) | 83(78%) | 18.73*** |

| Work construction | 200(50%) | 176(61%) | 24(22%) | |

| Monthly income | 17691 | 18121(545) | 16527(814) | |

| Living with more people due to economic crisis | 180(47%) | 121(43%) | 59(58%) | 10.4*** |

|

| ||||

| Trauma and Health | ||||

| Direct exposure | 1.8 (2.3) | 1.1 (.13) | 3.5(.48) | −4.43*** |

| Indirect exposure | 7.3 (4.4) | 6.6 (.45) | 9.5 (.28) | −6.95*** |

| Access (higher is more) | 14.1 (1.2) | 14.2(.09) | 13.6(.09) | 5.49*** |

| Health (higher is worse) | 33.5(6.2) | 32.1 (.38) | 37.4 (.85) | −6.95*** |

|

| ||||

| Sexual activity | ||||

| Vaginal sex (past month) | 2.1(.99) | 2.1(.07) | 2.2(.16) | |

| Sex worker (Moscow) | 367 (92%) | 266 (92%) | 100 (93%) | |

| # Sex workers past month | 1.5 (.99) | 1.4(.12) | 1.9(.64) | |

| Condom w/ sex worker (always) | 247(72%) | 183 (73%) | 64 (69%) | 2.90** |

| Condom w/ reg part (always) | 34(7%) | 24 (7%) | 10 (7%) | |

| Total Risk | .18(.15) | .17(.001) | .19 (.03) | |

| Total Protection | .88 (.42) | .90 (.04) | .84 (.06) | |

|

| ||||

| HIV & Health | ||||

| HIV Tested | ||||

| Know where to get tested | 263(70%) | 193(70%) | 69(69%) | |

| 277(70%) | 191(67%) | 86(80%) | 7.07** | |

| Worry about HIV | ||||

| Talk w/wife HIV | 4.9(1.6) | 4.9(.17) | 4.9(.20) | |

| Talk w/wife sexual activity | 50(11%) | 35(10%) | 15(15%) | |

| Talk w/wife condom in Moscow | 20(5%) | 10(3.5%) | 10(9.5%) | 8.18** |

| Talk w/reg part HIV | 15(4%) | 9(3%) | 6(6%) | |

| Talk w/reg part sexual activity | 128(34%) | 82(30%) | 46(45%) | 3.23* |

| Talk w/reg part condom in Moscow | 34(9%) | 19(6%) | 15(16%) | 3.61* |

| HIV knowledge | 54(14%) | 27(9%) | 27(27%) | 12.90*** |

| STD | 8.5(4.4) | 8.6 (.48) | 8.1 (.45) | |

| Alcohol use (>3 / wk) | 52(13%) | 36(12%) | 16(15%) | |

| 125(33%) | 95(34%) | 30 (29%) | ||

| Sex with alcohol | ||||

| Less condom use w/alcohol | 261(88%) | 190(91%) | 71(82%) | |

| 227(86%) | 172(90%) | 55(75%) | ||

| 4.28** | ||||

.1 < p

p < .05

p < .005

Note: For continuous variables, standard deviation reported for full sample, standard errors reported for estimates of PC-PTSD negative and positive values.

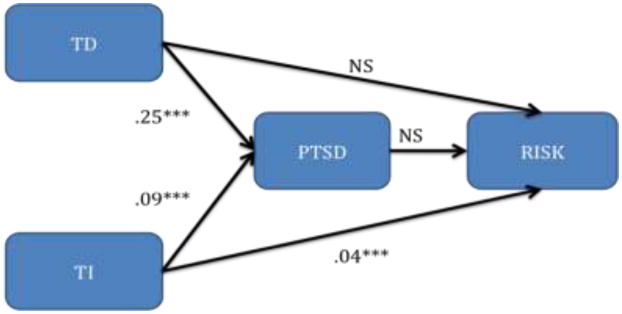

We constructed several multiple regression models with different independent variables (Table 5 and Figure 1). Our strategy was to regress each of the three trauma variables on the HIV risk and protection variables. The trauma related variables were: 1) Direct trauma exposure; 2) Indirect trauma exposure; 3) PTSD symptom total. The HIV risk and protection related variables were: 1) HIV sexual risk behaviors (number of times had vaginal sex in the past month; number of sex workers whose sexual services were used in the past month; a weighted sum of both; and less likely to use condoms when drinking alcohol); 2) HIV protective behaviors (frequency of condom use with sex workers; frequency of condom use with regular partners; and a weighted sum of both); 3) seven variables describing HIV related communication between the male migrant and sexual partners (e.g. talking with Tajik wife about condom use in Moscow).

Table 5. Comparing Multiple Regressions of Direct and Indirect Trauma.

| Direct Trauma | Indirect Trauma | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | R2 and p | F | R2 and p | |

| Talk w/ wife re sexual activity in Moscow | 6.16 | .04** | 8.52 | .01** |

| Talk w/ wife re HIV/AIDS | 3.27 | .02* | 3.83 | .01* |

| Talk w/ wife re having sex w/ sex workers | 3.09 | .03* | 11.85 | .02** |

| Talk w/ wife re condoms | - | NS | 6.17 | .01** |

| Talk w/ Moscow regular partner re HIV/AIDS | 12.76 | .02*** | 3.04 | .01* |

| Talk w/Moscow regular partner re having sex w/ sex workers | 12.01 | .09*** | - | NS |

| Talk w/ Moscow regular partner re using condoms for sex with women in Moscow | 10.22 | .04*** | 3.75 | .01* |

| Less likely to use condoms when drinking alcohol | 4.88 | .05** | - | NS |

.1 < p

p < .05

p < .005

Figure 1. Multiple Regressions of Trauma and HIV Sexual Risk (R2 and p values).

*.1 < p **p < .05 ***p < .005

TD: Direct trauma exposure

TI: Indirect trauma exposure

PTSD: PC-PTSD total

Risk: Weighted total of HIV sexual risk

Ethnographic Data from the Mixed Methods Study

Though this paper focuses on analysis of the survey data, it was part of a mixed methods (quantitative and qualitative) study that included a longitudinal ethnography with a purposive sample of 40 of the Tajik labor migrants. The analysis incorporates participants' narratives from the qualitative findings so as to explain the quantitative results following a mixed methods explanatory design (44). These qualitative findings mentioned were derived from a grounded theory approach to qualitative analysis of the ethnographic data (45, 46) that utilized Atlas/ti computer software (47).

Results

Demographic Characteristics

The recruited and enrolled sample consisted of 400 Tajik married male migrants whose composition roughly reflected the regional diversity of Tajik migrants in Moscow (13): 63 (16%) Dushanbe, 114 (29%) Khatlon, 89 (22%) Sughd, 41 (100%) GBAO, and 92 (23%) Subordinate Districts. There were 353 (87%) Sunni and 47 (13%) Ismaili Muslims. The average age was 31.5 years (SD = 6.1). Education level was 25 (6%) primary, 288 (72%) secondary, 38 (9%) college, and 10 (2%) university but no degree, 39 (10%) university degree. All men were married to a woman in Tajikistan. Twenty-three (6%) were also married to a woman in Russia and 352 (89%) had a regular female partner in Russia. The men had an average of 1.9 (S.D.=1.3) children in Tajikistan. The average income was 17,691 rubles earned per month (SD=5,447) (At approximately 30 rubles to one U.S. dollar, this is an average monthly earnings of just under $600). The respondents financially supported an average of 6.6 persons in Tajikistan (SD = 3.1).

Exposure to Traumatic Events

Table 1 indicates that the five most frequently endorsed direct trauma exposure items were: having been beaten by police (179; 45%); having ill health without access to medical care (76; 19%); being beaten by nationalists (69; 17%); lack of food or water (58; 14%); and a lack of shelter (58; 14%).

The five most frequently endorsed indirect trauma exposure items were: beaten by nationalists (n=322; 80%); beaten by police (n=296; 74%); imprisonment (n=270; (68%); ill health without access to medical care (n=266; 66%); serious injury (n=259; 65%) and workplace accident (n=260; 65%).

34% of migrants reported 1 or 2 direct traumas, whereas 32% reported between 9 and 11 indirect traumas. Indirect trauma exposure was directly correlated with direct trauma exposure (r(399) = .28, p <.0001) (Table 3).

PTSD Screen

The mean PC-PTSD score was 1.2 (SD=1.6). Slightly more than one-quarter of the respondents (107; 26%) endorsed a total of three or more items, suggesting that they were PTSD positive. The total number of items endorsed was: 0 items (n=234; 58%); 1 item (n=26; 6%); 2 items (n=33; 8%); 3 items (n=38; 9%); 4 items (n=69; 17%).

Three of the items on the PC-PTSD were endorsed at a similar frequency: nightmares or having thought about it (traumatic event(s)) when you didn't want to (n=129; 32%); having tried hard not to think about it (n=131; 33%); and being alert, careful, frightened (n=135; 34%). The fourth item was endorsed at a lower frequency: felt numb or detached from others, activities, surroundings (n=87; 22%).

Table 3 indicates that the PC-PTSD total score was directly correlated with both direct r(398) = .47, p < .001 and indirect r(398) = .29, p < .001 trauma exposure. Table 4 indicates that the PTSD-screen positive migrants were younger, F(1, 20) = 4.95, p < .001, and less educated, F(1, 20) = 10.37, p < .004, came from different regions in Tajikistan, F(4, 80) = 8.62, p < .001, lived with more people due to the economic crisis, F(1, 20) = 10.04, p < .038, had worse health status, F(1, 20) = −6.95, p < .001, and less health access, F(1, 20) = 5.49, p < .001.

Trauma, PTSD, and HIV Risk and Protection

We examined the relationship between HIV risk, trauma exposure, and PTSD. Figure 1 indicates that increased HIV risk behaviors was associated with higher indirect trauma exposure, R2 = .04, F(1, 20) = 40.4, p < .001, but not with direct trauma exposure or PC-PTSD score. Additionally, indirect trauma exposure was specifically associated with frequency of vaginal sex in the past month, R2 = .07, F(1, 20) = 12.52, p < .021, but not with number of sex workers visited in the past month.

Table 4 indicates that PC-PTSD score was associated with more talking with Tajik wives about sexual activity in Moscow, F(1, 20) = 8.18, p < .001. PC-PTSD score was associated with more talking with regular partners in Moscow regarding sexual activity in Moscow, F(1, 20) = 3.61, p < .072, regarding HIV/AIDS, F(1, 20) = 3.23, p < .087, and regarding condom use in Moscow, F(1, 20) = 12.9, p < .002.

Table 5 indicates that direct trauma, compared with indirect trauma, had a stronger association with talking with Moscow regular partner regarding sexual activity, R2 = .09, F(1, 20) = 12.01, p < .002, regarding HIV/AIDS, R2 =. 02, F(1, 20) = 12.76, p < .002, and regarding condom use, R2 = .04, F(1, 20) = 10.22, p < .004. Direct trauma, compared with indirect trauma also had a stronger association with being more likely to use condoms when drinking alcohol, R2 = .04, F(1, 20) = 4.88, p < .040. However, HIV protective behaviors (condom use with sex workers or regular partners) were not associated with direct or indirect trauma exposure or PC-PTSD score either in univariate tests (Tables 3 and 4) or regressions.

Select Narratives from Qualitative Data Explaining Quantitative Results

Qualitative findings were used to characterize the experiences of direct and indirect trauma and to explain their differential impact on HIV sexual risk.

Account of direct trauma

“I made a parody of the policeman who took us to the police station and he saw that and started to beat me. He beat me very hard. There was also a female policeman inside the police station where the policemen beat me and I felt more shame from the girl, than the pain from the policeman's kicks. Then he looked through my pockets and took away all my money. They left only 100 rubles in my pocket and let me go out.”

Account of indirect trauma

“Thanks to God I never meet the nationalists, but I heard they killed lot of Tajiks. They also get less active then they were before, just on the 21st of April when they have a holiday for Hitler's birthday. On this day they plan to kill as many migrants as possible. The migrants don't go out for work. Everybody is scared for his life.”

Comment comparing the impact of direct and indirect trauma

“Whoever had the experience of being beaten is more cautious now. He doesn't go out late and he doesn't pick up girls. He is afraid to go out. He doesn't want to be rude to girls. He doesn't go to pick up at tochkas (outdoor spots to pick up prostitutes). The one who just heard about that they didn't have the experience of being beaten. They just go and do whatever, they go out till late, pick up girls.”

Discussion

This survey found that many Tajik labor migrants are exposed to multiple types of traumatic events. Almost one-half reported having been beaten by police, and almost 20% experienced ill health without access to medical care, beatings by nationalists, a lack of food or water, or lack of shelter. This level of trauma exposure in Moscow underscores and validates the migrants' self-report of a sense of being unprotected.

One of four labor migrants (26%) screened PTSD-positive. This prevalence is slightly higher than the 20% mean for anxiety disorders (not just PTSD) found in a recent meta-analysis of anxiety disorders among labor migrants (8). However, in light of the results of a validation study (48), which found that 75% of those with a PTSD-PC screen score of 3 had PTSD on more rigorous assessment, the PTSD rate amongst the Tajik migrant study sample could be closer to 20%. Three of the PTSD symptom items were endorsed at equivalent rates (re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal) whereas the least endorsed item was numbness.

Though media reports have been focused on the harsh conditions in Moscow and on possible human rights violations (49), it is notable that the rates of PTSD amongst Tajik labor migrants in Moscow do not approach the 44% rate that Lindert's meta-analysis found in refugee populations. This suggests that the difficult and harsh conditions faced by the Tajik labor migrants in Moscow are comparatively less traumatogenic than those that experienced political violence and forced migration as refugees. It also suggests the possibility that Tajik labor migrants may have particular sources of resilience that need to be better understood.

Multiple regression analyses indicated no clear association between PTSD and HIV risk and protection. This is consistent with the existing literature on other traumatized populations which reflects that it is trauma exposure during childhood, not adulthood, that most impacts HIV risk behaviors. The trauma exposure of these migrants documented in the present study is not during childhood. Furthermore, intravenous drug use was a mediator in those prior studies, and only one of the migrants in our study reported any intravenous drug use (and that was less than once per week). Additionally, there were no significant differences in alcohol use associated with PTSD.

We found that PTSD was associated with some greater caution. Amongst the migrants who showed signs of trauma-related emotional distress, there was a tendency to take more precautions against sexual risks (e.g. talking more about risks with sexual partners being more likely to use of condoms when drinking alcohol).

These latter three findings suggest that Tajik migrants may have some protective factors against HIV risks not present in the majority Russian population. The extant literature suggests that adherence to Islamic values, such as abstinence from intoxicants and avoidance of extramarital sexual relations, may be protective against HIV transmission (50, 51, 52). The extent of individuals' adherence to Islamic principles, rather than mere affiliation, may be relevant to HIV risk and prevention and consequently requires additional examination. Additionally, it follows that the more that Tajik migrants become integrated and acculturated in Moscow, the less these protective factors may function. Increased participation in HIV-associated risk behaviors with increasing levels of acculturation has been noted among other migrants, including labor migrants from Latin America to the U.S. (53, 54, 55).

Overall, indirect traumas are even more prevalent than direct traumas amongst the sample. Approximately four of every five respondents have heard of others being beaten by nationalists; three of four heard about others being beaten by police; and two of every three have heard about others being imprisoned, having ill health without access to medical care, having a serious injury, or having had a workplace accident. This level of awareness of traumas to others both reflects and contributes to an atmosphere of intense fear for Tajik migrants in Moscow. Our prior ethnographic studies of Tajik male migrants in Moscow (18) found that men reported that they are “unprotected” in Moscow and that this may diminish their motivation and ability to diminish their HIV risk behaviors.

Our findings indicate that indirect trauma exposure is associated with increased HIV sexual risk, specifically having more frequent vaginal sex in the past month. We did not find such a relationship with direct trauma exposure and indicators of HIV risk.

These findings suggest that indirect trauma exposure and direct trauma exposure work differently when it comes to impacting HIV risk behaviors. Indirect trauma may add to labor migrants' sense of strain and insecurity, which they may attempt to relieve through sexual activity. However, direct trauma, which is more likely to cause PTSD, may lead male migrants to feel more threatened, and to behave more cautiously, in ways that unintentionally serve to reduce their HIV risk. This increased caution is also evidence by the migrants more frequent discussions with their regular partners about sexuality, HIV, and condom use.

Some prior studies of PTSD and HIV risk have led others to argue for incorporating mental health treatment into HIV prevention (56). Presently, Tajik migrant workers do not have access to mental health care for trauma related problems in either Moscow or in Tajikistan. Our findings indicate that irrespective of the HIV prevention issue, mental health care for labor migrants should be a public health priority. The matter of most concern to HIV prevention is that even if the migrants do get mental health treatment, will it make a difference in their HIV risk behaviors? The findings of this study imply that this is not likely, given the lack of association between PTSD and HIV risk behaviors.

For male migrants to be motivated to reduce their sexual risk behaviors, they would have to feel significantly more at risk from sexual contact than they presently do. Perhaps they would have to feel at risk in ways that they now do only with respect to the threats posed by simply being a migrant in Moscow (e.g. being beaten by police or nationalists). Put differently, in designing an HIV prevention intervention, we might look for ways to merge the different senses of risk with one another. Specifically, this argues for considering strategies aimed at enhancing the ways that HIV risks behaviors are represented so as to convey increased emotional levity in ways that could compete with their elevated reexperiencing and arousal symptoms. Importantly, this does not mean that we are trying to overly frighten them, but it does recognize that to compete with their existing sense of trauma, several degrees of amplification may be needed. For example, an intervention might explicitly use imagery and narratives that suggest that HIV beats up your immune system like nationalists and that migrants are feeling concerned about HIV risk “when they don't want to” and find themselves feeling “frightened.”

This study has several limitations. One, given the language and cross-cultural issues, there is always the possibility of misunderstandings or cultural bias in reporting. Two, this study used incentives for participation which may have introduced unmeasurable bias (e.g. a greater proportion of poorer migrants volunteering to participate in the study). Three, because this study did not ask about childhood trauma, our findings are limited to adult trauma exposure. Four, it is possible that our estimates of PTSD prevalence are biased towards the null due to our use of a PTSD screen rather than a full PTSD measure. Five, PTSD symptoms were not linked to particular traumatic events. Six, this study relied on survey data at one time point only, so it cannot address either longitudinal changes or causality. Six, Tajiks' experience may not be generalizable to other Central Asian labor migrants or to labor migrants generally. Further research is needed with rigorous, mixed methods studies, and intervention studies focused on the interaction between trauma, traumatic stress, and HIV risk and protection in labor migrants.

References

- 1.Anderson AF, Qingsi Z, Hua X, Jianfeng B. China's floating population and the potential for HIV transmission: a social-behavioural perspective. AIDS Care. 2003;15(2):177–85. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000068326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzgerald K, Chakraborty J, Shah T, Khuder S, Duggan J. HIV/AIDS knowledge and risk perception among female migrant farm workers in the midwest. J Immigr Health. 2003;5(1):29–36. doi: 10.1023/a:1021000228911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li L, Morrow M, Kermode M. Vulnerable but feeling safe: HIV risk among male rural-to-urban migrant workers in Chengdu, China. AIDS Care. 2007;19(10):1288–95. doi: 10.1080/09540120701402855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organista H, Carrillo H, Ayala G. HIV prevention with Mexican migrants: Review, critique, and recommendations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:S227–S239. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000141250.08475.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wollfers I, Fernandez I, Verghis S, Vink M. Sexual behaviour and vulnerability of migrant workers for HIV infection. Cult Health Sex. 2002;4(4):459–73. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang H, Li X, Stanton B, et al. Workplace and HIV-related sexual behaviours and perceptions among female migrant workers. AIDS Care. 2005;17(7):819–33. doi: 10.1080/09540120500099902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer MA, van Veen MG, Op de Coul ELM, Geskus RB, Coutinho RA, van de Laar MJW, Prins M. Migrants travelling to their country of origin: a bridge population for HIV transmission? Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84:554–55. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.032094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindert J, Ehrenstein OS, Priebe S, Mielck A, Brähler E. Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees--a systematic review and meta-analysis. SocSci Med. 2009;69(2):246–57. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lurie L. Psychiatric care in restricted conditions for work migrants, refugees and asylum seekers: experience of the Open Clinic for Work Migrants and Refugees, Israel. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2009;46(3):172–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steel J, Herlitz C, Matthews J, et al. Pre-migration trauma and HIV-risk behavior. Transcult Psychiatry. 2003;40(1):91–108. doi: 10.1177/1363461503040001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.UNAIDS. Eastern Europe and Central Asia Fact Sheet. Geneva: United Nations: 2004. Retrieved September 21, 2011 from: http://zagreb.usembassy.gov/root/pdfs/aids_epidemic_in_eastern_europe_and_central_asia.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly JA, Amirkhanian YA. The newest epidemic: a review of HIV/AIDS in Central and Eastern Europe. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14(6):361–71. doi: 10.1258/095646203765371231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erlich A. From refugee sender to labor exporter. Migration information source. 2006 Retrieved April 8, 2010 from: http://www.migrationinformation.org.

- 14.Olimova S, Bosc I. Labor Migration from Tajikistan. Geneva: International Organization on Migration; 2003. Retrieved November 29, 2010 from: http://www.iom.int/jahia/webdav/site/myjahiasite/shared/shared/mainsite/published_docs/studies_and_reports/Tajik_study_oct_03.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shakarishvili A, Dubovskaya L, Zohrabyan L, et al. Sex work, drug use, HIV infection, and spread of sexually transmitted infections in Moscow, Russian Federation. Lancet. 2005;366(9479):57–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66828-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asia Plus New Agency. HIV/AIDS rate rises in Tajikistan in 2010. 2011 Retrieved March 29, 2011 from: http://www.ilo.org/public/english/region/eurpro/moscow/news/2011/0121_2.htm.

- 17.Luo J, Golobof A, Bahromov M, Weine S. Powerlessness and HIV risk and protection amongst labor migrants. Poster presented at the International AIDS Conference; 2008; Mexico City, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weine SM, Bahromov M, Brisson A, Mizroev A. Unprotected Tajik migrant workers in Moscow at risk for HIV/AIDS. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10:461–68. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collings SJ. Childhood sexual abuse in a sample of South African university males: Prevalence and risk factors. S Afr J Psychol. 1991;21(3):153–58. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalichman SC, Gore-Felton C, Benotsch E, Cage M, Rompa D. Trauma symptoms, sexual behaviors, and substance abuse: correlates of childhood sexual abuse and HIV risks among men who have sex with men. J Child Sex Abus. 2004;13(1):1–15. doi: 10.1300/J070v13n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, Delahanty DL. The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):253–61. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown LK, Lourie KJ, Zlotnick C, Cohn J. Impact of sexual abuse on the HIV-risk-related behavior of adolescents in intensive psychiatric treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1413–15. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins PY, Berkman A, Mestry K, Pillai A. HIV prevalence among men and women admitted to a South African public psychiatric hospital. AIDS Care. 2009;21(7):863–7. doi: 10.1080/09540120802626188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malow RM, Devieux JG, Martinez L, Peipman F, Lucenko BA, Kalichman SC. History of traumatic abuse and HIV risk behaviors in severely mentally ill substance abusing adults. J Fam Violence. 2006;21:127–35. [Google Scholar]

- 25.VanDorn RA, Mustillo S, Elbogen EB, Dorsey S, Swanson JW, Swartz MS. The effects of early sexual abuse on adult risk sexual behaviors among persons with severe mental illness. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29:1265–79. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Child sexual abuse, HIV sexual risk, and gender relations of African-American women. Am J Prev Med. 1997;13(5):380–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simoni JM, Sehgal S, Walters KL. Triangle of Risk: Urban American Indian Women's Sexual Trauma, Injection Drug Use, and HIV Sexual Risk Behaviors. AIDS Behav. 2004;8(1):33–45. doi: 10.1023/b:aibe.0000017524.40093.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimerling R, Goldsmith R. Links between exposure to violence and HIV-infection: Implications for substance abuse treatment with women. Alcohol Treat Q. 2000;18(3):61–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutton HE, Treisman GJ, Hunt WR, et al. HIV risk behaviors and their relationship to post- traumatic stress disorder among women prisoners. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;42(4):508–13. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Catania JA, Paul J, Osmond D, et al. Mediators of childhood sexual abuse and high-risk sex among men-who-have-sex-with-men. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32(10):925–40. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelley JL, Petry NM. HIV risk behaviors in male substance abusers with and without antisocial personality disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000;19(1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKirnan DJ, Ostrow DG, Hope B. Sex, drugs, and escape: A psychological model of HIV risk behavior. AIDS Care. 1996;8(6):655–69. doi: 10.1080/09540129650125371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berm SL. Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychol Rev. 1981;88:354–64. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brettell C, Hollilfield JF, editors. Migration theory: talking across disciplines. New York, N.Y.: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weine SM, Feetham S, Kulauzovic Y, Besic S, Lezic A, Mujagic A, Muzurovic J, Spahovic D, Rolland J, Sclove S, Pavkovic S. A multiple-family group access intervention for refugee families with PTSD. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2008;34:149–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2008.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKay M, Chasse K, Paikoff R, et al. Family-level impact of the CHAMP Family Program: A community collaborative effort to support urban families and reduce youth HIV risk exposure. Fam Process. 2004;43(1):79–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04301007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agadjanian V. War, forced migration, HIV/AIDS risks in Angola. US National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2004. R03 HD45129. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Organista KC, Kubo A. Pilot survey of HIV risk and contextual problems and issues in Mexican/Latino migrant day laborers. J Immigr Health. 2005;7(4):269–81. doi: 10.1007/s10903-005-5124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mollica R, Caspi-Yavin Y. Measuring torture and torture-related symptoms. Psychol Assess. 1991;3:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weine SM, Becker DF, McGlashan TH, et al. Psychiatric Consequences of ethnic cleansing: Clinical Assessments and Trauma Testimonies of Newly Resettled Bosnian Refugees. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(4):536–42. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.4.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2004;9(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 43.SAS Institute Inc. SAS 9.1.3 Help and Documentation. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2000-2004. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Creswell JW, Clark VP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publishers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. California: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muhr T. ATLAS/ti 5.0 User's Manual and Reference (Version 5.0) Berlin: Scientific Software Development; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kimerling R, Trafton J, Nguyen B. Validation of a brief screen for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder with substance use disorder patients. Addict Behav. 2006;31(11):2074–79. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eurasianet. Moscow market tragedy refocuses attention of Tajik labor migration issue. 2006 Retrieved July 27, 2009 from http://www.eurasianet.org.

- 50.Gray B. HIV and Islam: Is HIV prevalence lower among Muslims? Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1751–1756. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gatrad AR, Sheikh A. Risk factors for HIV/AIDS in Muslim communities. Diversity in Health Soc Care. 2004;1:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Obermeyer CM. HIV in the Middle East. British Medical Journal. 2006;333:851–854. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38994.400370.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Organista KC. Towards a structural-environmental model of risk for HIV and problem drinking in Latino labor migrants” The case of day laborers. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2007;16(1/2):95–125. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shedlin MG, Decena CU, Oliver-Velez D. Initial acculturation and HIV risk among new Hispanic immigrants. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(7):32S–37S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levy V, Page-Shafer K, Evans J, Ruiz J, Morrow S, Reardon J, et al. HIV-related risk behavior among Hispanic immigrant men in a population-based household survey in low-income neighborhoods of Northern California. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32(8):487–490. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000161185.06387.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meader N, Li R, Des Jarlais DC, Pilling S. Psychosocial interventions for reducing injection and sexual risk behaviour for preventing HIV in drug users. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Jan;20(1):CD007192. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007192.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]