Abstract

In vitro studies have shown that p53 mediates a protective response against DNA damage by causing either cell-cycle arrest and DNA repair, or apoptosis. These responses have not yet been demonstrated in humans. A common source of DNA damage in humans is cigarette smoke, which should activate p53 repair mechanisms. The level of p53 is regulated by HDM2, which targets p53 for degradation. The G-allele of a polymorphism in intron 1 of HDM2 (rs2279744:G/T) results in higher HDM2 levels, and should be associated with a reduced p53 response and hence more DNA damage and corresponding tissue destruction. Similarly, the alleles of a polymorphism (rs1042522) in TP53 that encode arginine (G-allele) or proline (C-allele) at codon 72 cause increased pro-apoptotic (G-allele) or cell-cycle arrest activities (C-allele), respectively, and may moderate p53's ability to prevent DNA damage. To test these hypotheses we examined lung function in relation to cumulative history of smoking in a population-based cohort. The G-alleles in HDM2 and TP53 were found to be associated with accelerated smoking-related decline in lung function. These data support the hypothesis that p53 protects from DNA damage in humans and provides a potential explanation for variation in lung function impairment amongst smokers.

Introduction

The product of the p53 gene (TP53 in humans) is important for preventing cancers. We know this because defects in TP53 are responsible for Li-Fraumeni Syndrome, which results in multiple cancer phenotypes (1), and mutations in TP53 that either inactivate or alter p53 function are commonplace in many human malignancies (www.p53.iarc.fr). Furthermore, mice deleted for, or harbouring mutations within, the mouse p53 gene (Trp53) are highly cancer prone (2, 3).

How p53 functions to prevent cancers is not entirely clear. However, p53 is a transcription factor that responds to many different cellular stresses, including DNA damage (4, 5). p53 protein is present at very low concentrations in normal cells, but upon stress, p53 concentration increases several fold due to phosphorylation, which prevents it from being targeted for degradation by the E3 ligase HDM2 (6, 7). Once stabilised, p53 can transactivate several downstream genes which leads to (a) the induction of apoptosis to eliminate DNA damaged cells, (b) transient cell cycle arrest allowing DNA repair to occur, or (c) permanent cell cycle arrest (senescence) (4, 5). Thus, in these ways, p53 protects the organism from exposure to environmental insults, including DNA damage. These protective responses of p53 are all likely to contribute to tumour suppression to a greater or lesser extent, depending on tissue type and the nature of the stress.

Functional polymorphisms in HDM2 and TP53 have been identified in humans (8). The G-allele of a polymorphism in intron 1 of HDM2 (rs2279744:G/T) is known to result in increased levels of HDM2 due to the creation of a binding site for the common transcription factor Sp1 (9). This leads to reduced p53 protein levels and an attenuated p53 response. In some cases, individuals homozygous for this allele are more tumour prone (7). In TP53, the alleles of rs1042522 that encode arginine (G-allele) or proline (C-allele) at codon 72 are thought to influence the nature of the biological response of p53 to stress (10-15). p53 protein harboring the arginine residue (p53R72) has been reported to strongly interact with HDM2, resulting in enhanced nuclear export and association with the mitochondria. This appears to promote the apoptotic activity of p53. In contrast, there are data suggesting that p53P72 is more likely to induce cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage. Consistent with the evidence that these polymorphisms confer different biological activities on p53, their allele frequencies vary with both ethnicity and latitude (16).

Although the ability of p53 to respond to environmental stresses in cell culture and in animal models is well-documented (4, 5), there are few data demonstrating that this occurs in humans. A common environmental source of DNA damage in humans is cigarette smoke which contains many mutagenic compounds. If p53 is protecting cells from DNA damage caused by exposure to mutagens, such as those in cigarette smoke, the degree of protection should vary according to the strength and nature of the p53 response. Thus individuals with the G-allele of the HDM2 polymorphism (rs2279744:G/T) with a weaker p53 response may be less able to deal with exposure to cigarette smoke than individuals with the C-allele. Similarly, the degree of protection from exposure to cigarette smoke will vary with the biological nature of the p53 response and, therefore, individuals differing in the rs1042522 polymorphism should exhibit different degrees of protection. The hallmark of smoking-induced airway damage is a reduction in lung function--as measured by Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second (FEV1) and by the ratio of FEV1 to Forced Vital Capacity (FEV1/FVC)--which persists despite inhalation of a bronchodilator, indicating “irreversible” impairment (17). To test these hypotheses, these measurements were made in a population based cohort between ages 18 and 32 years in relation to cumulative history of smoking. We report that the extent of lung function decline after exposure to cigarette smoke exposure does indeed vary with the strength and nature of the p53 response.

Results

HDM2 G allele is associated with accelerated decline in lung function after cigarette smoke exposure

Post-bronchodilator measurements of FEV1 and FVC were performed in a population-based cohort study spanning young adulthood, from ages 18 to 32 years. Tobacco smoking was assessed on 4 occasions between ages 18 to 32. As expected, there was a significant main effect of cigarette smoke exposure on lung function change between these ages. The number of pack-years smoked was significantly associated with lower post-bronchodilator FEV1 values and lower FEV1/FVC ratios at age 32 after adjustment for these measures at age 18 (p=0.018 and p=0.001 respectively). However, there was no relationship between the HDM2 or TP53 polymorphisms and measures of lung function at either age 18 or 32 years (all p values >0.2).

Next, we examined whether the relationship between smoking and lung function was moderated by genetic variation in HDM2 (rs2279744:G/T). Among individuals homozygous for the G-allele, cumulative smoking history was associated with lower post-bronchodilator FEV1 values, whereas this association was not significant among individuals with the T-allele (Table 1), yielding a statistically significant interaction between the number of HDM2 G-alleles and smoking (pint=0.004). Thus, a weaker p53 response in cigarette smokers is associated with an accelerated decline in lung function. The association between smoking history and post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratios also appeared to be stronger among individuals homozygous for the G-allele than among T carriers, but the interaction between smoking and the number of HDM2 G-alleles did not reach statistical significance (pint=0.15).

Table 1.

Associations between lung function and smoking for rs2279744 HDM2 genotypes

| Genotype | n | coefficient | (95% CI) | p | pint | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 (ml) | TT | 308 | −0.6 | −5.9 to 4.8 | 0.837 | |

| T/G | 287 | −3.0 | −8.0 to 1.9 | 0.227 | ||

| GG | 73 | −19.6 | −30.9 to −8.2 | 0.001 | 0.004 | |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | TT | 308 | −0.05 | −0.12 to 0.01 | 0.110 | |

| T/G | 287 | −0.07 | −0.14 to 0.00 | 0.051 | ||

| GG | 73 | −0.16 | −0.32 to 0.01 | 0.070 | 0.154 |

Analyses by regression of lung function (dependent variable) and pack-years smoking (independent variable) with adjustment for sex and lung function at age 18. Coefficients (95% confidence intervals) represent the difference in lung function associated with each pack-year of smoking (thus, for example, a 5 pack-year smoking history is associated with a mean decline in FEV1 of 99ml in those homozygous for the G-allele). pint is the p value for the interaction between the number of G-alleles and smoking.

The TP53 G allele is associated with lung function decline in smokers

The above results suggest that p53 protects lung tissue from cigarette smoke exposure, as hypothesized. We therefore asked whether smoking-related impairment of lung function varied according to the nature of the p53 response. Lung function measurements in relation to smoking history were analysed with respect to the TP53 rs1042522 polymorphism. Individuals homozygous for the G-allele (encoding p53R72) were more susceptible to smoking-induced lung function impairment (Table 2). Among the G-allele homozygotes, smoking history was significantly associated with lower values for FEV1 and FEV1/FVC, whereas these associations were not significant for carriers of at least one C-allele. The interactions between the number of G-alleles and smoking were statistically significant for both post-bronchodilator FEV1 and the FEV1/FVC ratio (pint=0.020 and 0.037, respectively). Thus, the degree of protection from lung-function decline after cigarette smoke exposure appears to vary according to both the strength and nature of the p53 response.

Table 2.

Associations between lung function and smoking for rs1042522 TP53 genotypes

| Genotype | n | coefficient | (95% CI) | p | pint | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 (ml) | CC | 48 | 5.9 | −6.6 to 18.3 | 0.346 | |

| C/G | 247 | −1.7 | −7.6 to 4.1 | 0.560 | ||

| GG | 373 | −7.0 | −11.6 to −2.4 | 0.003 | 0.020 | |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | CC | 48 | 0.00 | −0.14 to 0.13 | 0.970 | |

| C/G | 247 | −0.05 | −0.13 to 0.03 | 0.220 | ||

| GG | 373 | −0.11 | −0.18 to −0.05 | <0.001 | 0.037 |

Analyses by regression of lung function (dependent variable) and pack-years smoking (independent variable) with adjustment for sex and lung function at age 18. Coefficients (95% confidence intervals) represent the difference in lung function associated with each pack-year of smoking. pint is the p value for the interaction between the number of G-alleles and smoking.

Accelerated decline in lung function after cigarette smoking varies with the number of risk alleles

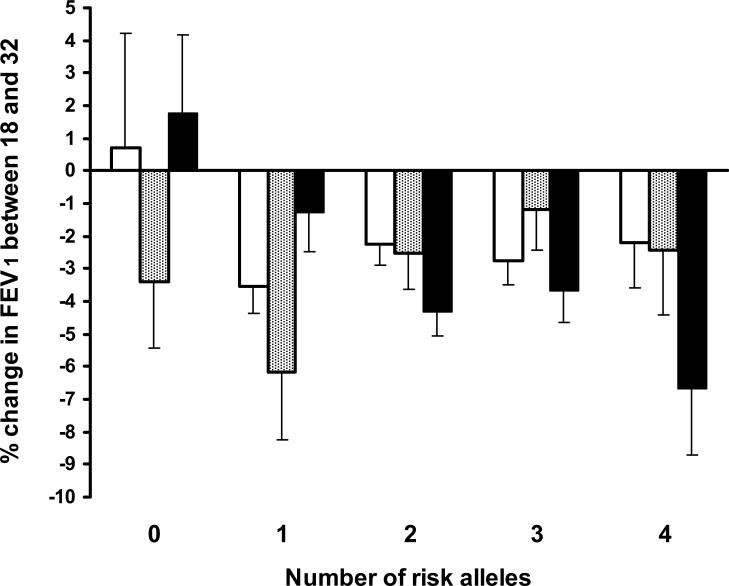

To test whether combinations of the HDM2 and TP53 polymorphisms influenced smoking-related lung function decline, we calculated a score based on the number of “risk” alleles (G-alleles for HDM2, and G-alleles for TP53). (There was no significant association between the HDM2 and TP53 variants, χ2=4.54, p=0.34.) Thus, an individual homozygous for both T-alleles for rs2279744 and C-alleles for rs1042522 had 0 risk alleles, whereas an individual homozygous for G-alleles at both loci had 4 risk alleles. Regression analyses of the association between smoking and lung function among these subgroups are shown in Table 3. There were significant interactions between smoking and the number of risk alleles for post-bronchodilator FEV1 and FEV1/FVC (pint=0.001 and 0.020, respectively). The association between heavy smoking and decline in post-bronchodilator FEV1 was stronger in those with more risk alleles (Fig 1). Thus, individuals with combinations of the rs2279744 G-allele and the rs1042522 G-allele appear to be at greater risk of developing smoking-related impairment of lung function.

Table 3.

Associations between lung function and smoking according to the number of HDM2 and TP53 risk alleles

| No. of risk alleles | n | coefficient | (95% CI) | p | pint | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 (ml) | 0 | 29 | 15.7 | −2.1 to 33.4 | 0.080 | |

| 1 | 129 | 3.2 | −5.1 to 11.5 | 0.446 | ||

| 2 | 277 | −7.0 | −12.3 to −1.7 | 0.010 | ||

| 3 | 189 | −2.9 | −9.5 to 3.8 | 0.395 | ||

| 4 | 44 | −19.9 | −35.4 to −4.4 | 0.013 | 0.001 | |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 0 | 29 | 0.14 | −0.03 to 0.30 | 0.095 | |

| 1 | 129 | −0.05 | −0.15 to 0.06 | 0.403 | ||

| 2 | 277 | −0.09 | −0.16 to −0.03 | 0.007 | ||

| 3 | 189 | −0.09 | −0.18 to 0.00 | 0.060 | ||

| 4 | 44 | −0.20 | −0.44 to 0.04 | 0.099 | 0.020 |

Analyses by regression of lung function (dependent variable) and pack-years smoking (independent variable) with adjustment for sex, lung function at age 18. Coefficients (95% confidence intervals) represent the difference in lung function associated with each pack-year of smoking. pint is the p value for the interaction between pack-years smoking and the number of risk alleles for HDM2 GG and TP53 GG (e.g. HDM2 genotype TT and TP53 genotype CC = 0 risk alleles: HDM2 genotype GG and TP53 genotype GG = 4 risk alleles).

Figure 1. Mean percent change in FEV1 between ages 18 and 32 according to smoking history and the number of risk alleles.

White bars indicate non-smokers (no pack years, n=350), grey bars indicate light smokers (less than 5 pack years, n=97), black bars indicate heavy smokers (at least 5 pack years, n=221). The trend across risk allele groups is significant for moderate-heavy smokers (p=0.005) but not for non- or light smokers (p=0.83 and 0.12 respectively). Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

There was an unexpected trend to improved lung function amongst smokers with no risk alleles (Table 3). It seems most likely that this is a chance finding since the sample was small (n=29) and the trend was not statistically significant. If this group was removed from the analysis, the interaction between the number of risk alleles and smoking remained statistically significant for FEV1 but not for FEV1/FVC (pint=0.008 and 0.21, respectively).

Discussion

The observation of greater smoking-induced impairment of FEV1 in individuals who are homozygous for the HDM2 G-allele is consistent with its role in attenuating the p53 response. Similarly, the difference in the liability of the TP53 rs1042522 alleles to confer susceptibility to smoking-induced lung damage may relate to their differential ability to promote the apoptotic and cell cycle arrest functions of p53. p53R72 (encoded by the G-allele) binds more tightly to HDM2 than p53P72 (encoded by the C-allele) (10), and this interaction promotes export of p53 from the nucleus (15) to the mitochondrial membrane where it mediates apoptosis (11, 12). p53P72 by contrast is reported to be more effective than p53R72 at causing cell cycle arrest (13, 14). Thus, our data showing that those with p53P72 alleles appear to be more resistant to smoking-induced lung damage suggest that cell cycle arrest and DNA repair are more important than apoptosis in protecting lung tissue from smoke-induced DNA damage. Although ultimately less efficient than apoptosis at removing DNA damaged cells, activation of repair by p53P72 would afford considerable protection from DNA damage and, at the same time, minimise tissue damage after exposure to cigarette smoke.

Lung function naturally declines slowly after reaching a peak in young adulthood. Our data suggest that the extent to which smoking accelerates this decline depends on the strength of the p53 response. However, age 32 is too young to detect serious smoking-related lung damage and the relationship between our observations and advanced smoking-related diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer remains unknown.

The finding that functional genetic polymorphisms in the p53 pathway moderate the effect of cigarette smoking on lung function requires replication in independent cohorts. However, we think it is unlikely that our findings are due to chance. First, the findings are biologically plausible as p53 plays a key role in regulating the cellular response to genotoxic stress. Second, the nature of the p53 responses associated with these HDM2 and TP53 genotypes are biologically consistent with each other, and in combination, showed the strongest association. Third, we were able to rule out the presence of gene-environment correlations; that is, there were no significant differences in the pack-year smoking histories of individuals as a function of the number of risk alleles in HDM2 (p=0.51), TP53 (p=0.43) or the sum of HDM2 and TP53 risk alleles (p=0.95). Fourth, measurements of lung function were made 14 years apart, which allowed us to document that genetic polymorphisms involved in p53 function moderated the effect of smoking on ‘within-individual’ changes in lung function over the course of young adulthood. Fifth, smoking exposure was ascertained via repeated, prospective assessments, largely negating the problems associated with retrospective recall.

In summary, we found that common polymorphisms of the gene for p53, and its principal regulator HDM2, are associated with accelerated smoking-related decline in lung function in young adults. These data may provide an explanation for differences in the susceptibility of individuals to the adverse effects of smoking. Furthermore, they provide novel evidence that p53 can mediate physiologically adaptive responses to genotoxic insults in humans.

Methods

The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study is described in detail elsewhere (18-20). Briefly this is a longitudinal study of an unselected birth cohort of 1037 individuals (52% male) born in Dunedin in 1972/1973. The cohort represents the full range of socioeconomic status in New Zealand's South Island and Study members are mostly of New Zealand/European ethnicity. The cohort has been assessed repeatedly since birth. Here we report data on lung function and smoking assessed during the 14-year period between ages 18 to 32 years. The Otago Ethics Committees approved the study and written informed consent was obtained at each assessment.

Lung function

Post-bronchodilator spirometry was measured at ages 18 and 32 years using an Ohio computerized spirometer (Ohio instruments) and a SensorMedics body plethysmograph (Yorba Linda, CA), respectively. At least 3 acceptable manoeuvres were obtained with the best FEV1 and FVC from any of the tests reported and used for calculation of FEV1/FVC (21). Spirometry was measured 10 minutes after inhalation of 5mg/ml salbutamol nebulised for 2 minutes at age 18 and after 200 μg salbutamol via a metered dose inhaler using a large volume spacer at age 32. A portable spirometer (Spiropro, Sensormedics, Yorba Linda CA) was used to test Study members who were unable to sit in the plethysmograph or were unable to attend the research unit (n = 10 in this analysis). At each age, standing height was measured to the nearest millimetre.

Cigarette smoking

Personal smoking history was obtained from the Study members at ages 18, 21, 26 and 32 years. Cumulative smoking history to age 32 was calculated from these assessments. One pack year is defined as the equivalent of 20 cigarettes a day for one year.

Genotyping

Both polymorphisms were genotyped using primer extension-mass spectrometry (SEQUENOM, San Diego, CA). All PCR and MassEXTEND™ reactions were conducted utilising standard conditions using 2.5 ng of genomic DNA per sample (22). Primers used to genotype the 309G/T polymorphism in intron 1 of HDM2 (c.-5+309G>T; rs2279744:g.G>T) were -5’-ACGTTGGATGTCGGAGGTCTCCGCGG-3’ (forward PCR primer), 5’-ACGTTGGATGCCGACAGGCACCTGCGATC-3’ (reverse PCR primer) and 5’-TCCGGACCTCCCGCGCCG-3’ (extension primer). The primers used to genotype the R72P polymorphism in TP53 (c.215G>C; rs1042522:g.G>C) were 5’-ACGTTGGATGGGCCGCCGGTGTAGGAGC-3’ (forward PCR primer), ACGTTGGATGCCAGGTCCAGATGAAGCTCC-3’ (reverse PCR primer) and 5’-GCCAGAGGCTGCTCCCC-3’ (extension primer). Automated analysis of these samples by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization/time-of-flight mass spectrometry was performed on a SEQUENOM–Bruker MassARRAY mass spectrometer. A randomly selected 10% of PCR amplified products from the cohort were re-genotyped using restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis with BstUI (TP53) or MspA1I (HDM2). Results demonstrated exact concordance with those obtained with mass spectrometry.

Statistical analysis

The influence of smoking (in pack years) and HDM2 or TP53 genotype (coded as 0, 1, or 2 risk alleles, respectively) on spirometric lung function was assessed using linear regression with adjustments for lung function at age 18 (to adjust for any pre-existing differences in lung function), sex, and standing heights at age 18 and 32 (to adjust for sex- and height-related differences in expected lung function at each age). Interactions between genotype and the airway response to smoking were assessed by computing multiplicative genotype x smoking terms in these regression analyses. Separate analyses were repeated for each HDM2 and TP53 genotype. The effect of smoking on lung function was assessed amongst those with different combinations of these polymorphisms by repeating the analyses amongst those with different numbers of “risk” alleles (HDM2 rs2279744 G-alleles and TP53 rs1042522 G-alleles). The possibility that there may be a gene-environment correlation such that the genetic polymorphisms of HDM2 or TP53 influenced smoking behavior was assessed by comparing the smoking histories of the different genotypes. Analyses excluded pregnant women and were limited to Study members who reported that all four grandparents had European ethnicity. Initial analyses found no evidence that the effects of smoking on lung function differed for men and women. Hence, in subsequent analyses, sexes were grouped together with an adjustment in the models. All analyses were performed using Stata version 10 (College Station, TX).

Acknowledgements

The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Unit is funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand. DNA collection and extraction was funded by the University of Wisconsin. Dr Sears holds the AstraZeneca Chair in Respiratory Epidemiology at McMaster University. Avshalom Caspi holds a Royal Society Wolfson Merit Award. Professor Braithwaite is supported by the Cancer Institute NSW. We are grateful to the Study members and their parents for their continued support. We also thank Dr Phil A Silva, the study founder. This study was in part supported by a Dunedin School of Medicine Strategic Research Initiative Grant, the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (grants MH45070, MH49414 and MH077874), and the U.K. Medical Research Council (G0100527). Mr T Manley is thanked for assistance with the genotyping.

Footnotes

The authors have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Malkin D, Li FP, Strong LC, Fraumeni JF, Nelson CE, Kim DH, Kassel J, Gryka MA, Bischoff FZ, Tainsky MA, et al. Germ Line P53 Mutations in A Familial Syndrome of Breast-Cancer, Sarcomas, and Other Neoplasms. Science. 1990;250:1233–1238. doi: 10.1126/science.1978757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA, Butel JS, Bradley A. Mice Deficient for P53 Are Developmentally Normal But Susceptible to Spontaneous Tumors 1. Nature. 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang GA, Iwakuma T, Suh YA, Liu G, Rao VA, Parant JM, Valentin-Vega YA, Terzian T, Caldwell LC, Strong LC, et al. Gain of function of a p53 hot spot mutation in a mouse model of Li-Fraumeni syndrome 1. Cell. 2004;119:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vousden KH, Lu X. Live or let die: the cell's response to p53 2. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrc864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braithwaite AW, Prives CL. p53: more research and more questions 1. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:877–880. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Momand J, Zambetti GP, Olson DC, George D, Levine AJ. The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the p53 protein and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation 2. Cell. 1992;69:1237–1245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90644-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bond GL, Hu W, Levine AJ. MDM2 is a central node in the p53 pathway: 12 years and counting 5. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2005;5:3–8. doi: 10.2174/1568009053332627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy ME. Polymorphic variants in the p53 pathway 3. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:916–920. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bond GL, Hu W, Bond EE, Robins H, Lutzker SG, Arva NC, Bargonetti J, Bartel F, Taubert H, Wuerl P, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 promoter attenuates the p53 tumor suppressor pathway and accelerates tumor formation in humans 1. Cell. 2004;119:591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumont P, Leu JI, Della PAC, III, George DL, Murphy M. The codon 72 polymorphic variants of p53 have markedly different apoptotic potential 1. Nat Genet. 2003;33:357–365. doi: 10.1038/ng1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chipuk JE, Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L, Droin NM, Newmeyer DD, Schuler M, Green DR. Direct activation of Bax by p53 mediates mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis 1. Science. 2004;303:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1092734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leu JI, Dumont P, Hafey M, Murphy ME, George DL. Mitochondrial p53 activates Bak and causes disruption of a Bak-Mcl1 complex 1. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:443–450. doi: 10.1038/ncb1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pim D, Banks L. p53 polymorphic variants at codon 72 exert different effects on cell cycle progression 3. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:196–199. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas M, Kalita A, Labrecque S, Pim D, Banks L, Matlashewski G. Two polymorphic variants of wild-type p53 differ biochemically and biologically 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1092–1100. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu ZK, Geyer RK, Maki CG. MDM2-dependent ubiquitination of nuclear and cytoplasmic P53 1. Oncogene. 2000;19:5892–5897. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beckman G, Birgander R, Sjalander A, Saha N, Holmberg PA, Kivela A, Beckman L. Is p53 polymorphism maintained by natural selection? 2. Hum Hered. 1994;44:266–270. doi: 10.1159/000154228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, Fukuchi Y, Jenkins C, Rodriguez-Roisin R, van Weel C, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary 1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hancox RJ, Poulton R, Greene JM, Filsell S, McLachlan CR, Rasmussen F, Taylor DR, Williams MJ, Williamson A, Sears MR. Systemic inflammation and lung function in young adults 1. Thorax. 2007;62:1064–1068. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.076877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasmussen F, Taylor DR, Flannery EM, Cowan JO, Greene JM, Herbison GP, Sears MR. Risk factors for airway remodeling in asthma manifested by a low postbronchodilator FEV1/vital capacity ratio: a longitudinal population study from childhood to adulthood 1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1480–1488. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2108009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sears MR, Greene JM, Willan AR, Wiecek EM, Taylor DR, Flannery EM, Cowan JO, Herbison GP, Silva PA, Poulton R. A longitudinal, population-based, cohort study of childhood asthma followed to adulthood 1. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1414–1422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Thoracic Society Standardization of Spirometry - 1994 Update 1. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1995;152:1107–1136. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bansal A, van den Boom D, Kammerer S, Honisch C, Adam G, Cantor CR, Kleyn P, Braun A. Association testing by DNA pooling: An effective initial screen. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:16871–16874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262671399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]