Abstract

As medical education undergoes significant internationalization, it is important for the medical education community to understand how different countries structure and provide medical education. This article highlights the current landscape of medical education in China, particularly the changes that have taken place in recent years. It also examines policies and offers suggestions about future strategies for medical education in China. Although many of these changes reflect international trends, Chinese medical education has seen unique transformations that reflect its particular culture and history.

Recent proposals for medical education in China

China's rapidly growing economy has produced profound changes in Chinese society; these changes include education. In 2008, Ren et al. analyzed medical education in China (Ren et al. 2008), when they pointed out that great improvements have been made in Chinese medical education since 1975, but if compared to medical education in a well-developed western country, Chinese medical education still needs to be strengthened in several areas, such as admission, teaching methodology, clinical training and standardization of curricula. Since 2008, a series of educational and health policies have led to further change in Chinese medical education. These policies and their impact are described below.

Practice points

Great changes have been made in Chinese medical education since 2008.

A series of medical education policies facilitate medical education change after the Chinese government announced a major comprehensive health reform effort in 2009.

Many changes, such as medical education standards, integrated courses and new teaching methods have taken place.

A series of measures should be implemented to deepening medical education reform, including strengthening provincial level organization, addressing faculty concerns, building encouraging system and evaluation system. Ongoing financial support from government is necessary.

China's healthcare reform policies

In 2009, the Chinese government announced a major comprehensive set of health reforms. The goal of the new health reform policies was to establish a basic health service system that would provide universal coverage to the population it served. In order to achieve this goal, from 2009 to 2011, the Chinese government adopted five reform foci:

accelerating the construction of the basic health insurance system,

establishing a national essential drug list,

establishing a primary-level health service system,

promoting the equalization of basic public health services and

facilitating a pilot reform program in public hospitals.

In order to establish the primary-level health service system, according to “Chinese Government's Opinions on Deepening the Medical and Health Care system reform”(The Centre People's Government of the People's Republic of China 2009), the specialties of General Practice or Family Medicine should be developed to cover the shortage of general practitioners. Medical schools must adjust the proportion of students in different medical training tracks and control the number of enrolled students in order to provide qualified health professionals for the primary-level health service system.

“Opinions on Strengthening Medical Education and Enhancing Quality”

In response to “Chinese Government's Opinions on Deepening the Medical and Health Care system reform,” the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health issued “Opinions on Strengthening Medical Education and Enhancing Quality” in 2009. This report highlighted the following recommendations (Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China 2009):

Medical schools should change their curricula. Natural sciences, medical sciences and the humanities should be integrated with clinical skills and professionalism throughout the curriculum. The curriculum will incorporate student-oriented learning styles in order to facilitate curriculum change and help students to develop life-long learning, critical thinking and innovation ability. Assessment methods also need to be developed.

Accreditation of medical schools should be implemented in order to develop a medical education quality assurance system in which government, social organizations and medical schools are all stakeholders.

Graduate medical education and continuing medical education must be facilitated in order to develop a complete medical education system.

The proportion of students in different medical education training tracks needs to be adjusted. At present, the dominant model is the 5-year medical education program. In addition, 3-year programs provide a work force for rural areas, and should be retained. However, new, 8-year programs, with class sizes of less than 100, should be developed in top medical schools.

Efforts should be taken to provide an adequate healthcare work force for rural areas. Medical schools should develop general practice as a specialty and other relevant courses of study.

“Standards for Basic Medical Education of 5-year program”

As the 5-year medical education program is the dominant program in China, the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health issued “Standards for Basic Medical Education of 5-year program” (Chinese Government Public Information Online 2008). This document is informed by the World Federation for Medical Education's “Standards for Basic Medical Education” published in 2003 and revised in 2012 (World Federation for Medical Education 2012) and the “WHO Guidelines for Quality Assurance of Basic Medical Education in the Western Pacific Region” (World Health Organization Western Pacific Regional Office 2001). “Standards for Basic Medical Education of 5-year program” is the guideline for accreditation and medical education quality assurance and includes two major sections that define accreditation standards:

The minimum essential requirement of medical graduates, including the learning outcomes of professionalism, knowledge and clinical skills.

The requirements and standards for medical schools all require review and improvement, including mission and goals, curriculum, assessment of students, students, faculty, educational resources, program evaluation, science research, governance and administration, continuous renewal.

The “Outline of China's National Plan for Medium and Long-Term Education Reform and Development”

In 2010, the Chinese government issued the “Outline of China's National Plan for Medium and Long-Term Education Reform and Development” (The Centre People's Government of the People's Republic of China 2010). The outline calls for medical schools to set up “medical professional excellency programs” as one measure to promote higher education quality. In response to this outline, the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health issued two documents in 2012. One is “Opinions on Medical Education Reform” (Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China 2012a) and the other is “Opinions on implementing excellent physician education program” (Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China 2012b).

“Opinions on Medical Education Reform”

“Opinions on Medical Education Reform” states several reform measures.

The number of enrolled medical students’ should be decided by the demands of the health service system and the education resources of medical schools. The Ministry of Education should reduce the number of enrolled students at some medical schools and even close some medical schools that fail to pass accreditation.

The future medical education system should include five years undergraduate medical education and 3-year residency training program.

Graduate medical education leading to a clinical master degree should be combined with residency training.

The curriculum of the 8-year medical education program should be changed and internationalized in order to provide health professionals trained to the highest standards.

In order to provide qualified general practitioners for China's numerous rural villages, the curriculum of the 3-year training track should be changed by combining the 3-year training program with a 2-year general practice residency training program that leads to becoming an assistant general practitioner. The government encourages medical schools to enroll students from rural villages who pay no tuition fees, but must agree to go back to their village after graduation.

“Opinions on implementing excellent physician education programs”

The Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health issued “Opinions on implementing excellent physician education programs” following the release of “Opinions on Medical Education Reform.” “Opinions on implementing excellent physician education programs” is a guideline for implementing medical education reform. It points out that the Chinese government will fund medical education reform projects from 2012 to 2022. It also details the priority funding areas of reform, the requirement for applicants and applying process. The priority funding areas are as follows:

The reformation of 5-year medical education program.

The reformation of graduate medical education leading to a clinical master's degree. Graduate medical education leading to a clinical master degree should be combined with residency training.

The reformation of curriculum of 8-year medical education program.

The development of rural medical education program.

Recent changes and the current status of medical education in China

Medical schools

As of January 2012, there are 630 medical schools in China, including 350 secondary medical–pharmaceutical schools, which provide a 3-year medical education curriculum and 280 medical–pharmaceutical universities, which provide medical education programs varying from 5 to 8 years. The total number of medical students in China is 1,760,000 in 2012 (Xinhua net 2013).

Compared to the status in 2008 (Ren et al. 2008), the present number of secondary medical–pharmaceutical schools decreased from 500 to 350, whereas the number of medical–pharmaceutical universities increased from 180 to 280. The total number of medical schools decreased from 680 to 630. This decline reflects governmental control over the number of medical schools and adjustments to the proportion of different type of programs according to “Opinions on Strengthening Medical Education and Enhancing the Quality” in 2009. Some medical schools have merged with neighboring universities, some secondary medical–pharmaceutical schools have been promoted to medical universities after developing their education resources and faculty and some medical schools have been closed.

The various medical schools are administrated by different ministries of the government, from central government to provincial governments. The Ministry of Education oversees most of the central government-administrated medical–pharmaceutical universities. Only Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) is administrated by the Ministry of Health.

Medical education training track

Before 2008 there were four types of undergraduate medical education programs in China: 3-year, 5-year, 7-year and 8-year programs. After the 2009 “Opinions on Strengthening Medical Education and Enhancing the Quality,” and especially after 2012 “Opinions on Medical Education Reform” and “Opinions on implementing excellent physician education program,” the Ministry of Education standardized medical education training programs to three types, 3-year, 5-year and 8-year programs. The 7-year programs are being phased out gradually.

Although the 8-year medical education program started in China in 1917, until 2003, PUMC was the only medical school that provided an 8-year program. In 2004, the Ministry of Education decided to start 8-year programs in five other medical schools. As of October 2010, there were 16 medical schools with 8-year programs (Fan et al. 2011).

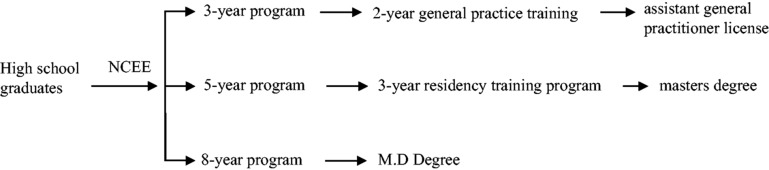

The 3-, 5- and 8-year programs all have differing goals. The 8-year curriculum is designed to provide health professionals who have an MD degree. The 5-year program trains physicians to a bachelor degree level. Graduates of a 5-year program can receive the master's degree if they finish a 3-year residency training program. The 3-year training track is designed to provide general practitioners for rural villages. After the 3-year program, the graduate who finishes a subsequent 2-year general practice training program receives an assistant general practitioner license.

Accreditation

In response to the “Standards for Basic Medical Education of 5-year program,” the Ministry of Education sponsored the Committee on Medical Education and the Committee on Clinical Medical program in 2008. This Committee began accreditation of 5-year programs in 2008 and had reviewed eight medical schools by 2012 (Institute of Medical Education Peking University 2012). The accreditation standard is stated in the “Standards for Basic Medical Education of 5-year program.” The usual period of full accreditation is 6–8 years. There are no standards for 3- or 8-year programs at this point, and thus, no accreditation process.

Admission

Typically, medical students are admitted direct from high school after they pass a National College Entrance Examination (NCEE), which is administered by the Ministry of Education. Usually the applicants for the 8-year medical education program must have a higher score than applicants to the 3- and 5-year programs. The applicants for the 5-year program must have a higher score than the applicants for the 3-year program.

After the Ministry of Education defined 8-year medical education curricula in some top medical schools, more and more medical educators in leading medical schools have recognized and advocated that medical education is a professional education that requires mature trainees. This has led some medical schools to change the admission process of their 8-year medical education program to focus more on applicants already having an undergraduate university degree. For example, PUMC provides 22% (20/90) of its enrollment places to the first year students of Tsinghua University, a top university in China. The applicants participate in an interview conducted by a committee. The goal of this interview is to understand the motivation and personal fitness of the applicant for medical study. Similarly, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (ZUSM) implemented a 4+4 medical education program, which means that the high school students ZUSM admit must undertake four years of undergraduate education in biology and complete the academic requirement of the bachelor's degree in biology. They can elect some bio-medical courses when they are at the university. After finishing the four years of biology study, students in good standing who wish to continue their medical education can transfer to the 4-year medical school program.

Curriculum change

The curriculum of the 3-year program usually includes one year of pre-clinical education and two years of clinical training (Schwarz et al. 2004). The 5-year program is the only program which has government-specified standards. According to “Standards for Basic Medical Education of 5-year program,” a 5-year medical education program should include natural sciences, bio-medical sciences, psycho-social topics, behavioral science, medical ethics and public health. Clinical training is a critical part of the curriculum and includes Diagnostics, Internal Medicine, Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics, Pediatric, Family Medicine, Emergency Treatment and no less than 48 weeks of clerkship rotations.

As the 8-year program is a new program in China, the curricula in different medical schools are diverse. For example, PUMC allocates 2.5 years for premed education, 1.5 years for pre-clinical education and 4 years for clinical training. Students take premed education in comprehensive universities, usually a biology concentration in a university. They must study subjects required by the medical school. After finishing the premed phase of their education, students transfer to the medical school for medical study, but at that point, they do not get a bachelor degree.

Although the curricula of different medical training tracks are diverse, they have some common characteristics. The typical curriculum structure of most medical education programs in China is discipline-based curricula. The dominant teaching methodology is the didactic lecture. However, in response to “Opinions on Medical Education Reform,” there are a few medical schools that have changed their curricula to an interdisciplinary structure, such as the ZUSM and the West China Medical Center of Sichuan University. Efforts have also been made in leading medical colleges to develop new teaching methodologies in order to promote student-oriented learning. ZUSM has initiated an integrated clerkship rotation (Yu et al. 2009). Problem-based learning (PBL), standardized patients (SPs) and simulation have been adopted at several schools. Almost all leading medical schools with an 8-year medical education program use the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) as a comprehensive clinical assessment method.

Excellent physician education program

In response to “Opinions on implementing excellent physician education programs,” the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health approved 125 medical schools to start 178 “excellent physician education programs” by the end of 2012. These programs include 26 excellent health professionals programs, 72 programs that combine a 5-year medical education with 3-year residency training, 39 3-year rural medical education programs and 41 programs that combine three years of medical education with two years of general practice residency training (Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China 2012c). Thus, the number of medical schools which can institute an 8-year medical education program will increase from 16 at present to 26 in the next several years. In order to encourage more medical schools to apply for the rural medical education program and to provide a curriculum model, the rural medical education program undertaken by Capital Medical University has been awarded the special National Higher Education Award by the Ministry of Education. The award is the supreme honor for education in China.

Medical licensure examination

The Chinese Medical Licensure Examination began in response to the 1999 “Decree of the President of the People's Republic of China” (The National People's Congress 1999). The examination is administered once a year by the National Medical Examination Center. Applicants must submit a certificate of completion of formal undergraduate medical education in China or in a foreign country. Graduates of the 5-year programs should have 1-year residency training experience after graduation. Graduates of 8-year programs can sit for the licensure examination during their graduate year if they have one year clinical training similar to residency training.

The examination measures two major educational outcomes: clinical knowledge and clinical skills. Clinical knowledge is measured by 600 multiple-choice questions. It is conducted in the middle of September all around the nation. The clinical knowledge portion of the examination is divided into four parts: bio-medical topics and professionalism; internal medicine; surgery; and Gynecology & Obstetrics and Pediatrics. Each of these four parts takes 2.5 hours. The whole clinical knowledge examination lasts two days.

Clinical skills are measured through an OSCE. It is administered in different geographical examination districts, each consisting of several provinces. Examinees take the OSCE at accredited hospitals in June or July. In 2011, the pass level for clinical knowledge was 356/600 and for clinical skills, 60/100. About 30% of examinees pass the exam (The National Medical Examination Center 2013).

Residency training

The first residency training program in China started in 1921 at PUMC Hospital, but there was no national graduate medical education system until 2004. In 2005, the Ministry of Health established the National Council for Graduate Medical Education in order to promote standardized residency training programs. Residency training is required for all medical school graduates after 2005. In 2010, the Chinese Government issued “The national Medium and Long-Term talent development plan (2010–2020)” (The Centre People's Government of the People's Republic of China 2010). That plan required more standardization in residency training programs, overseen by the Ministry of Health. Residency programs consist of two parts: a 3-year rotating internship and 3-7 years specialty training element. The hospitals which provide residency training programs are accredited by the national or provincial health administration departments every 3–5 years. There are presently about 2000 residency training programs in more than 300 hospitals. As noted above, some residency training programs provided by medical schools’ teaching hospital are combined with 5-year medical education program, leading to a clinical master's degree.

Figure 1 summarizes the different ways that a student enters the medical profession in China.

Figure 1.

Varying ways to enter the medical profession in China.

Concerns about the present status and changes of medical education in China

Even compared to the status of medical education in China five years ago (Ren et al. 2008), great progress has been made. Many strategies mentioned by Ren and colleagues have been initiated. The pre-medical component of an 8-year medical education program has been separated from the medical school component. The government has set the standards for 5-year medical education program, and uniform textbooks and accreditation standards of these programs have been developed. New teaching and assessment methodologies, such as PBL, case-based learning, SP and objective structured clinical evaluations, have all been adopted. A series of medical education policies have been issued, the number and frequency of which is rare in China's history. However, in spite of the development of Chinese medical education, there are ongoing concerns that focus on the weaknesses listed below:

Although the Ministry of Education has initiated “excellent physician education programs” and other medical education reform issues, few of these changes are being instigated. The main reason is lack of detailed organization and reformative aspirations at provincial level. In a sense, the provincial administrators have not realized that medical education reform is important for medical service quality assurance system. They also have not realized that medical education is a professional education.

Although many medical schools have developed integrated courses and some use new teaching methodologies, these attempts are too often superficial, and the goals of these teaching methods have not been achieved. Part of the underlying reason for this is that the faculty members worry about changing the system. Medical education reform means that the faculty will have to pay more attention in learning and understanding pedagogical methods and new medical education innovations. Faculty need to know how the change will affect them personally and professionally.

Medical schools show a lack of enthusiasm for deepening medical education reform. Part of the reason is lack of reward and status for any change agents. Change is never a checklist, it is always of a complex nature; there is no step-by-step shortcut to transformation. Rewarding good change performance is important to promote lasting change (Fullan 2002).

Although the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health issued standards for the 5-year medical education programs, there are no standards for 8-year or 3-year education programs. Standards are essential for accreditation and education quality assurance, the lack of standards leads to diverse curricula and a lack of accreditation for 8-year and 3-year programs.

Strategies for deepening changes and improving medical education in China

In order to deepen the medical education reforms and improve medical education in China, certain strategies need to emerge. These are as follows:

International communications, seminars and lobbying from specialty societies should be implemented to change the provincial administrators’ viewpoint. The change of viewpoint on medical education held by administrators is very important. Administrators must become more aware that medical education is a professional education; the purpose of medical education is to transmit the knowledge, impart the skills, and inculcate the values of the profession in an appropriately balanced and integrated manner (Cooke et al. 2006). Medical education should be changed in important ways that augment the quality of the graduates and the health care they provide.

Social mobilization in medical schools needs to be launched in order to address faculty's concerns and help them to understand the importance of medical education reform. More international communication and cooperation is also necessary in order to share and learn from the successful experiences in medical education from other countries. These measures will help faculty members prepare for and accept the change.

Faculty development that focuses on teaching methods, assessment and innovative medical education needs to be established, implemented and strengthened. Medical educator programs should be standardized and required for faculty development.

The Government's education administrators should develop an appropriate motivation and reward system for medical education reform. Rewards and honors for changing medical schools and pioneer faculty are necessary to encourage deepening and expanding these changes.

Recruiting good-performance leaders, such as medical schools’ presidents and deans, is important. Re-culturing is the name of the medical education reform. Much of the present change is structural and superficial. Transforming the culture leads to deep, lasting change. Leaders who can create a fundamental transformation of the learning cultures of schools and of the teaching profession itself is also important (Fullan 2002).

Systematic and reliable evaluation for medical education reform should be developed; further changes will be guided by evaluation findings. In the absence of program evaluation, change is likely to drift or to be driven by anecdotal evidence and rumors (Lindberg 1998).

Ongoing financial support from central Government is necessary to facilitate and strengthen the changes.

The Ministry of Education or specialty societies should issue separate standards of 8-year and 3-year education program as soon as possible. Standards and education quality assurance is especially important for the 8-year programs, which have the goal of developing the highest levels of health professionals.

Conclusion

Since most of Chinese medical education reform policies have been issued only after 2009, the campaign of improving medical education in China can be described as being in its early infancy. Medical education reform involves the hard, day-to-day work of re-culturing; restructuring the Chinese medical education system will undergo many more significant changes in future years. With the development of Chinese society and its economy, people are calling for a high-quality medical service. In order to provide high-quality medical service, standardized quality training programs and quality assurance system are paramount for the future.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Biographies

QIN ZHANG is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Social Medicine and General Family Medicine, Zhejiang University. She is also the Director of President Office, Peking Union Medical College.

LIMING LEE, MD, is a Professor of Peking University School of Medicine. He is also the Vice President of Peking Union Medical College.

LARRY D. GRUPPEN, Ph.D, is a Professor of Medical Education and Chair of Department of Medical Education of University of Michigan Medical School.

DENIAN BA, MD, is a Professor of Peking Union Medical College. He is also the Honorary Dean of Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

References

- Chinese Government Public Information Online. 2008. Standards for Basic Medical Education of 5-year program. Beijing: Chinese Government Public Information Online. [Accessed 20March 2013]. Available from: http://govinfo.nlc.gov.cn/gtfz/zfgb/jyb/200811/201010/t20101012_456813.html?classid=423 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cooke M, Irby D, Sullivan W, Ludmerer K. American medical education 100 years after the Flexner report. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra055445. Available from: www.nejm.org September 28, 2006:1339–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan XG, Li YP, Hu WF, Bi XY, Liang L. A comparative study on enrollment and cultivation between 8-year M.D program in China and 4 plus 4 M.D program in U.S.A. Fudan Educ Forum. 2011;9(3):93–96. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fullan M. 2002. The change leader. Educ Leadership(5):16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medical Education Peking University The result of Accreditation of Clinical Medical Education Program. Institute of Medical Education Peking University; Beijing: 2012. [Accessed 20 March 2013]. Available from: http://ime.bjmu.edu.cn/art/2011/10/14/art_4905_63001.html (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg M. The process of change: Stories of the journey. Acad Med. 1998;73(9): s4–s10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China Opinions on Strengthening Medical Education and Enhancing Quality. Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China; Beijing: 2009. [Accessed 20March 2013]. Available from: http://www.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/s3864/201010/xxgk_109604.html (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China Opinions on medical education reform. Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China; Beijing: 2012a. [Accessed 20March 2013]. Available from: http://www.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/s6548/201206/xxgk_137754.html (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China Opinions on implementing excellent physician education program. Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China; Beijing: 2012b. [Accessed 20 March 2013]. Available from: http://www.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/s6548/201206/xxgk_137753.html (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China The list of the first batch of Excellent Physician Education Programs. Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China; Beijing: 2012c. [Accessed 20 March 2013]. Available from: http://www.moe.edu.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/s6548/201211/144809.html (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ren XF, Yin JC, Wang BJ, Schwarz R. A descriptive analysis of medical education in China. Med Teach. 2008;30:667–672. doi: 10.1080/01421590802155100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz MR, Wojtczak A, Zhou TF. Medical education in China’s leading medical schools. Med Teach. 2004;26(3):215–222. doi: 10.1080/01421590310001642939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Centre People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China Chinese Government’s Opinions On Deepening the Medical and Health Care system reform. The Centre People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China; Beijing: 2009. [Accessed 20 March 2013]. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2009/content_1284372.htm (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The Centre People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China Outline of China's National Plan for Medium and Long-term Education reform and Development. The Centre People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China; Beijing: 2010. [Accessed 20 March 2013]. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2010-07/29/content_1667143.htm (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The Centre People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China The national Medium and Long-Term talent development plan (2010–2020) The Centre People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China; Beijing: 2010. [Accessed 20 March 2013]. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2010-06/06/content_1621777.htm (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The National Medical Examination Center The Introduction to the Medical Licensure Examination. The National Medical Examination Center; Beijing: 2013. [Accessed 20 March 2013]. Available from: http://www.nmec.org.cn/yszgks/ksjj/ksjj.htm (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The National People's Congress Decree of the President of the People’s Republic of China. The National People's Congress; Beijing: 1999. [Accessed 20 March 2013]. Available from: http://www.people.com.cn/zgrdxw/faguiku/yywsh/F47-1030.html (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- World Federation for Medical Education Standards for Basic Medical Education – The 2012 Revision. World Federation for Medical Education; Copenhagen: 2012. [Accessed 20 March 2013]. Available from: http://wfme.org/news/general-news/263-standards-for-basic-medical-education-the-2012-revision. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Western Pacific Regional Office WHO guidelines for quality assurance of basic medical education in the Western Pacific Region, World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific; Manila, the Philippines: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Xinhua net There are more than 600 medical-pharmaceutical schools and universities in China. Xinhua net; Beijing: 2013. [Accessed 20 March 2013]. Available from: http://news.xinhuanet.com/edu/2012-01/24/c_111459291.htm (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu F, Xu LX, Ding Lu, Luo W, Wang QQ. The integrated clerkship: An innovative model for delivering clinical education at the Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):886–894. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a859d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]