Abstract

Interferon beta-1a is available as an immunomodulating agent for relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis. Common side effects include flu-like symptoms, asthenia, anorexia, and administration site reaction. Kidney disorders are rarely reported. In this study we describe the case of a woman who has been undergoing treatment with interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis for 5 years. She developed a hemolytic-uremic syndrome with intravascular hemolysis in a context of severe hypertension. A kidney biopsy showed a thrombotic microangiopathy. This observation highlights an uncommon side effect of long-term interferon beta-1a therapy. Pathophysiological mechanisms leading to this complication might be explained by the antiangiogenic activity of interferon.

Keywords: thrombotic microangiopathy, interferon beta, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, antiangiogenic activity

Introduction

Thrombotic microangiopathies (TMA) are microvascular occlusive disorders characterized by systemic or intrarenal aggregation of platelets, thrombocytopenia, and mechanical injury to erythrocytes. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) represent the two most frequently encountered clinical presentations of TMA. Sometimes TTP and HUS can overlap, and the clinical distinction between these two entities may be difficult to discern. The typical form of HUS occurs most commonly in children about a week after an episode of bloody diarrhea caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7. But infections with other E. coli serotypes also cause HUS in children and adults. Less frequently, there is no preceding diarrheal illness, and this form of the disease is known as atypical HUS (aHUS), and can either be sporadic or, when more than one member of a family is affected, familial.1 Atypical HUS designates a primary disease caused by a disorder in complement alternative pathway regulation.2 In both cases, there is an acute kidney disease.

Although TMA has multiple etiologies, adverse effects of drugs have been increasingly reported for several years as probable causes of TMA.3 Drug-associated TMA can be an acute, immune-mediated disorder or the result of gradual, dose-dependent toxicity.4 Interferon alpha (IFNα) has been implicated in the development of lesions of thrombotic microangiopathies in patients treated for chronic myeloid leukemia.5 We speculate that interferon beta-1a (IFNβ-1a) therapy may be involved in the development of TMA, and we propose a hypothesis for the mechanism by the antiangiogenic activity of interferon (IFN) to explain this.

Here we report the case of a woman who has been treated for 5 years with IFNβ-1a for multiple sclerosis (MS), and has developed renal failure with hypertension due to TMA with clinical presentation of HUS.

Case report

The 38-year-old Caucasian woman was diagnosed with MS in August 2006. Treatment was started 7 months later with IFNβ-1a (Rebif®, Merck Serono Europe Limited, London, UK) and before this, no treatment was initiated. The IFNβ therapy was well tolerated for 5 years, with ibuprofen and acetaminophen also taken to treat flu-like symptoms. In recent years, she reported using oxcarbazepine therapy for neuralgia and a clonazepam therapy for cramps, but these drugs were taken over a short period of time.

For several weeks before the first admittance in our hospital, she reported a history of asthenia, cramps, headaches, and anorexia with weight loss. Discovery of anemia motivated the hospital admission of the patient.

At admission, the patient showed evidence of kidney insufficiency in the context of severe hypertension (180/130 mmHg). Laboratory investigations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Laboratory test results during hospital admissions

| Test item | First hospitalization

|

Second hospitalization

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At admission | At discharge (7th day) | At admission | At discharge (7th day) | |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 211 | 257 | 465 | 501 |

| Serum urea (mmol/L) | 13 | 13.9 | 13.9 | 25.6 |

| Protein total (g/L) | 59 | 54 | 64 | 62 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (IU/L) | 923 | 287 | 285 | 194 |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min estimated with MDRD formula) | – | 18 | – | 8 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 80.3 | 112 | 96 | 103 |

| Haptoglobin (g/L) | <0.1 | 0.35 | 1.14 | |

| Platelets (×109/L) | 167 | 294 | 330 | 353 |

| Schistocytes | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| C3 complement (g/L) | 1.18 | – | 1.16 | – |

| C4 complement (g/L) | 0.29 | – | 0.28 | – |

| Autoantibodies (*) | Negative | – | – | – |

Notes:

Autoantibodies included anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-GBM antibodies and anti-phospholipids. - indicates results not available.

Abbreviations: MDRD, modification of diet in renal disease; GBM, glomerular basement membrane.

Viral, bacteriological, and immunological studies, including antinuclear antibodies, were all etiologically negative. The results of gene mutation analysis in Factor H, Factor I, membrane cofactor protein (MCP), complement C3 and Factor B were also negative.

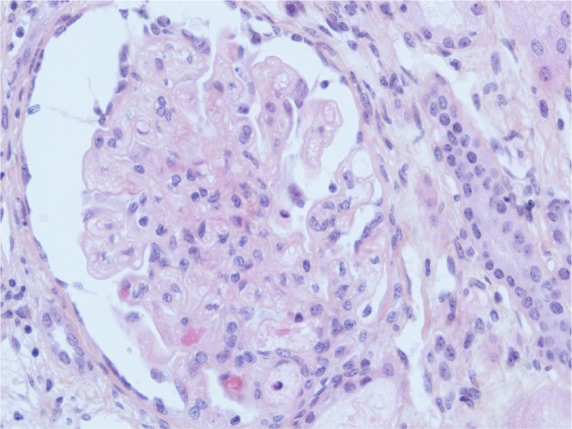

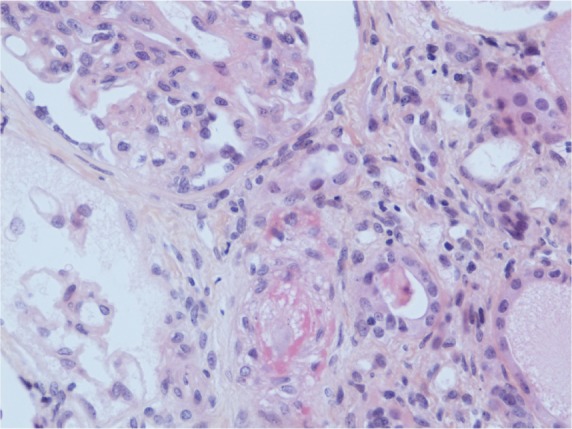

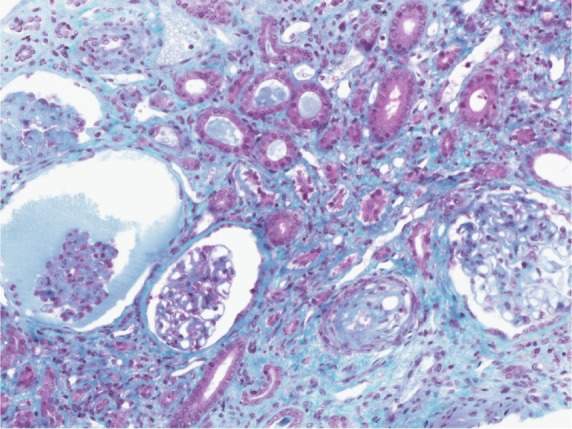

A kidney biopsy revealed both acute and chronic lesions of TMA. A few glomeruli presented with capillary-loop double contours, fibrin thrombi, and zones of mesangiolysis (Figure 1). One arteriole showed marked mucoid intimal expansion with focal fibrinoid necrosis (Figure 2). Chronic ischemic changes were predominant, with diffuse interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, extensive ischemic changes in glomeruli, and severe fibrous intimal thickening of interlobular arteries (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Acute glomerular lesion.

Notes: There is global thickening of glomerular capillary walls caused by subendothelial expansion associated with focal mesangiolysis and a few capillary thrombosis (HES ×400 magnification).

Abbreviation: HES, hematoxylin, eosin, saffron.

Figure 2.

Acute arteriolar lesion.

Notes: Mucoid intimal thickening with focal fibrinoid necrosis is responsible for occlusion of the lumen (HES ×400 magnification).

Abbreviation: HES, hematoxylin, eosin, saffron.

Figure 3.

Severe chronic ischemic changes.

Notes: There is diffuse interstitial fibrosis with focal tubular atrophy. The three glomerular (on the left) show severe wrinkling of the basement membranes with sclerotic changes. The interlobular artery shows marked intimal fibrous thickening with resultant severe narrowing of the lumen (trichrome ×200 magnification).

During the 7 days of hospitalization, a symptomatic treatment with red blood cell transfusion resulted in the correction of anemia. Blood pressure control was initially achieved with intravenous nicardipine therapy and relayed with triple antihypertensive therapy (propranolol, amlodipine, and irbesartan). Consequently, IFNβ-1a was discontinued. At the end of hospitalization, kidney failure persisted in this patient, consistent with the chronic lesion identified on kidney biopsy.

One month after the first episode, the patient was readmitted following difficulties in controlling blood pressure (140/100 mmHg) and kidney function deterioration (Table 1). During the second admittance there was no biological argument in favor of a recurrence of TMA: no biological argument for mechanical hemolysis, and complement C3 and C4 levels were normal. The introduction of urapidil, an adrenergic alpha-1 receptor antagonist, was required for blood pressure control, in addition to the triple therapy already established. At the end of 7 days of hospitalization, the blood pressure control was achieved (110/80 mmHg).

Nine months after the last hospitalization, the patient has chronic kidney disease with stabilization of creatinine 225 μmol/L and creatinine clearance at 22 mL/min (estimated using the modification of diet in renal disease [MDRD] formula). She is not receiving dialysis, and her hypertension is controlled with irbesartan, furosemide (switched to urapidil) and propranolol. The patient is currently neurologically stable, and she is not undergoing treatment for MS.

Discussion

IFNs are cytokines that mediate antiviral, antiproliferative, and immunomodulatory activities. IFNβ-1a is prescribed for the treatment of relapsing forms of MS to slow down the development of physical disability and decrease the frequency of clinical exacerbations.

IFN therapy is associated with adverse effects such as flu-like symptoms, asthenia, anorexia, and injection site reaction. Renal side effects are uncommon, but severe manifestations are reported, including acute renal failure related to acute tubular necrosis, or acute interstitial nephritis, hemolytic-uremic syndrome, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and minimal change disease.6 These side effects are more often associated with IFNα therapy rather than IFNβ. TMA caused by IFNα therapy has been reported for several years.7

The concept that the TMA presented by our patient was secondarily related to IFNβ treatment is supported by several factors.

Concerning the concomitant medications, the literature does not describe TMA induction by ibuprofen and acetaminophen, moreover, oxcarbazepine and clonazepam were taken several years before the first hospitalization and over a short period.

The patient presented with an increased blood pressure (180/130 mmHg) before the first hospitalization, and severe or malignant hypertension may accompany TMA.8 The pathological changes from kidney damage in malignant hypertension are sometimes similar to renal lesions in HUS/TTP, leading to difficulties in the differential diagnosis for other TMA etiologies.9 Among the conditions linked to TMA, malignant hypertension is associated with a predominance of vascular rather than glomerular findings.10 In our case, the patient had no medical history of hypertension, and the IFNβ therapy is not known to be associated to the occurrence of hypertension. She also had no sign of malignant hypertension.

The presence of antiphospholipid antibodies can be induced by IFN therapy: Piette et al suggested the role of antiphospholipid antibodies in hemolytic-uremic syndrome induced by IFNα.11 The presence of antiphospholipid antibodies was found in patients who have been diagnosed with MS since they can be induced by IFN therapy.12 In our case, autoimmune serologies were negative, including antiphospholipid antibodies.

Genetic abnormalities in the complement cascade are associated in approximately 50% of patients with atypical HUS.13 Six different mutations in genes coding for various components of the complement alternative pathway (Factor H, Factor I, Factor B, MCP, thrombomodulin, and C3 complement component) have been identified to date.14–16 In our case, there is no evidence in favor of gene abnormalities as the results of genetic analysis were negative.

Activity of von Willebrand protease factor was not assessed in our case report. An ADAMTS 13 (A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin 1 motifs) deficiency could be due to autoantibodies against various epitopes of this protease during treatment with IFNα-2a.17 This could explain the formation of occlusive platelet thrombi in microvessels, but no similar mechanism has been described with IFNβ.

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the mechanisms that can lead to TMA development with IFN therapy, but none can be considered in this case. The pathogenesis of TMA may involve inhibition of vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) in renal podocytes.4 VEGF stimulates signal transduction pathways and transcriptional programs through activation of its receptor, VEGFR2.18 These events are essential for de novo formation of blood vessels (ie, angiogenesis, a process that involves proliferation and migration of endothelial cells),14 while this process is inhibited by cytokines of the type 1 IFN family (including IFN-α/β).19 IFN-α/β exert their effects via binding to the type 1 IFN receptor and activation of Janus kinases and signal transducers, and activators of transcription.20 The role of VEGF in renal physiology is not completely known,21 but it has been involved in the pathophysiology of several renal diseases, and TMA is a lesion commonly reported with anti-VEGF drugs. Also IFN therapy could be considered as an etiological agent to TMA through this antiangiogenic activity.

Both clinical presentations of TMA, TTP and HUS are listed in the Summary of Product Characteristics of IFNβ-1a (Rebif®), and were identified during the postmarketing surveillance.22

A literature review in the PubMed database was carried out, and to our knowledge, this is the sixth case of TMA induced by IFNβ. A summary of TMA case reports induced by IFNβ is presented in Table 2. In one case, the patient developed systematic lupus erythematosus, positive antiphospholipid antibodies, and acute renal failure due to thrombotic microangiopathy. The TMA may be associated with systematic lupus erythematosus or antiphospholipid syndrome, and it is difficult to speculate on the role of IFN therapy.23 Moreover, there are few reported cases of systematic lupus erythematosus linked to IFNβ therapy.24

Table 2.

Summary of thrombotic microangiopathy case reports induced by interferon beta (IFNβ) therapy from literature review

| Authors | Year | Age of patient | Indication of IFNβ-1a therapy | Duration of therapy | Clinical | Laboratory investigations | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ubara et al25 | 1998 | 66 | HCV | 44 days | HUS | Discontinuation of IFNβ | Remission | |

| Herrera et al26 | 1999 | N/A | MS | 2 weeks | TTP | Discontinuation of IFNβ + plasmapheresis | Chronic kidney disease | |

| Hansen et al23 | 2009 | 41 | MS | Several years | Renal failure + SLE + APS | Antinuclear-antibodies and antiphospholipid positive | Discontinuation of IFNβ + plasmapheresis + steroids + mycophenolate mofetil | Chronic kidney disease |

| Broughton et al27 | 2011 | 53 | MS | 8 years | Renal failure + mild hypertension | Discontinuation of IFNβ + lisinopril | Chronic kidney disease | |

| Olea et al28 | 2012 | 37 | MS | 5 months | Renal failure + severe hypertension | Discontinuation of IFNβ + steroids + enalapril + irbesartan | Remission |

Abbreviations: APS, anti-phospholipid syndrome; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; HUS, hemolytic-uremic syndrome; MS, multiple sclerosis; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura; HCV, hepatitis C virus; N/A, not available.

For two other cases, the therapy duration was very short (44 days and 2 weeks),25,26 while a hypothesis suggests that the cumulative effects of IFN may result in the development of renal lesions.27 TMA occurred several months or years after starting the treatment with IFN-α,5 whereas other nephropathies are usually diagnosed in the first weeks of treatment. The duration of IFN therapy may therefore be the cause of some cumulative endothelial toxicity, which corroborated with our patient, who has been receiving IFNβ-1a for 5 years.

A search in the French Pharmacovigilance Database using the terms “thrombotic microangiopathy”/“thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura”/“hemolytic-uremic syndrome” combined with “interferon beta-1a” found ten other cases. The notifications with renal biopsy confirming the diagnosis of TMA only are presented in Table 3. For two cases, the investigations showed an ADAMTS 13 deficiency (with anti-ADAMTS 13 autoantibodies for one case), and for one case, the patient serum was positive for antiphospholipid antibodies. For all notifications, the delay of IFN therapy was consistent with the hypothesis of cumulative effects.

Table 3.

Summary of thrombotic microangiopathy notifications induced by interferon beta-1a (IFNβ) from French Pharmacovigilance Database

| Year | Age | Duration of treatment | Disease | Clinical | Treatment | Laboratory investigations | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 47 | 1 year | MS | Proteinuria | Discontinuation of IFNβ | Remission | |

| 2007 | 58 | 5 years | MS | HUS + hypertension | Discontinuation of IFNβ + plasmapheresis + steroids | Chronic kidney disease | |

| 2008 | 55 | 6 years | MS | TTP | Discontinuation of IFNβ + plasmapheresis + steroids + rituximab | IgG anti-ADAMTS 13 positive | Remission |

| 2009 | 66 | 1 year | MS | HUS + hypertension | Discontinuation of IFNβ + urapidil | Remission | |

| 2009 | 65 | 1 year | MS | Nephrotic syndrome | NA | NA | |

| 2010 | 38 | 10 years | MS | TTP | Discontinuation of IFNβ + plasmapheresis + steroids | NA | |

| 2011 | 44 | 3 years | MS | Renal failure + hypertension | Discontinuation of IFNβ + plasmapheresis | Antinuclear-antibodies positive | Chronic kidney disease |

| 2012 | 52 | >3 years | MS | HUS + hypertension | Discontinuation of IFNβ + plasmapheresis + nebivolol | Decreased activity of ADAMTS 13 | Chronic kidney disease |

Abbreviations: ADAMTS, A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin 1 motifs; Ig, immunoglobulin; NA, not available; HUS, hemolytic-uremic syndrome; MS, multiple sclerosis; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

In conclusion, our observations added to the other reported cases, support the hypothesis that IFNβ-1a is a causative agent in the occurrence of TMA. A serious renal prognosis with chronic kidney disease was reported in most of these cases. Assessing kidney function and detecting the onset of hypertension is justified to identify renal toxicity as soon as possible during IFNβ therapy.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Noris M, Remuzzi G. Atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(17):1676–1687. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0902814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warwicker P, Goodship TH, Donne RL, et al. Genetic studies into inherited and sporadic hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int. 1998;53(4):836–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.1998.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medina PJ, Sipols JM, George JN. Drug associated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome. Curr Opin Hematol. 2001;8(5):286–293. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.George JN, Terrell DR, Vesely SK, Kremer Hovinga JA, Lämmle B. Thrombotic microangiopathic syndromes associated with drugs, HIV infection, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and cancer. Presse Med. 2012;41(3 Pt 2):e177–e188. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuber J, Martinez F, Droz D, Oksenhendler E, Legendre C, Groupe D’étude Des Nephrologues D’ile-de-France (GENIF) Alpha-interferon-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: a clinicopathologic study of 8 patients and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81(4):321–331. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200207000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aravindan A, Yong J, Killingsworth M, Suranyi M, Wong J. Minimal change disease with interferon-beta therapy for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. NDT Plus. 2010;3(2):132–134. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvey M, Rosenfeld D, Davies D, Hall BM. Recombinant interferon alpha and hemolytic uremic syndrome: cause or coincidence? Am J Hematol. 1994;46(2):152–153. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830460220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaughan CJ, Delanty N. Hypertensive emergencies. Lancet. 2000;356(9227):411–417. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02539-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang B, Xing C, Yu X, Sun B, Zhao X, Qian J. Renal thrombotic microangiopathies induced by severe hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2008;31(3):479–483. doi: 10.1291/hypres.31.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halevy D, Radhakrishnan J, Markowitz G, Appel G. Thrombotic microangiopathies. Crit Care Clin. 2002;18(2):309–320. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(01)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piette JC, Papo T. Potential role for antiphospholipid antibodies in renal thrombotic microangiopathy induced by interferon-alpha. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10(9):1781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.IJdo JW, Conti-Kelly AM, Greco P, et al. Anti-phospholipid antibodies in patients with multiple sclerosis and MS-like illnesses: MS or APS? Lupus. 1999;8(2):109–115. doi: 10.1191/096120399678847461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malina M, Roumenina LT, Seeman T, et al. Genetics of hemolytic uremic syndromes. Presse Med. 2012;41(3 Pt 2):e105–e114. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2011.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warwicker P, Goodship TH, Donne RL, et al. Genetic studies into inherited and sporadic hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int. 1998;53(4):836–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.1998.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richards A, Kemp EJ, Liszewski MK, et al. Mutations in human complement regulator, membrane cofactor protein (CD46), predispose to development of familial hemolytic uremic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(22):12966–12971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135497100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Dragon-Durey MA, Blouin J, et al. Complement factor I: a susceptibility gene for atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome. J Med Genet. 2004;41(6):e84. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.019083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moake JL. Thrombotic microangiopathies. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(8):589–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: basic science and clinical progress. Endocr Rev. 2004;25(4):581–611. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sidky YA, Borden EC. Inhibition of angiogenesis by interferons: effects on tumor- and lymphocyte-induced vascular responses. Cancer Res. 1987;47(19):5155–5161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aaronson DS, Horvath CM. A road map for those who don’t know JAK-STAT. Science. 2002;296(5573):1653–1655. doi: 10.1126/science.1071545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schrijvers BF, Flyvbjerg A, De Vriese AS. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in renal pathophysiology. Kidney Int. 2004;65(6):2003–2017. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ema.europa.eu [homepage on the Internet] Summary of product characteristics of Rebif® [updated 2013 April 18] Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/Accessed June 26, 2013

- 23.Hansen T, New D, Reeve R, Donne R, Stephens W. Acute renal failure, systemic lupus erythematosus and thrombotic microangiopathy following treatment with beta-interferon for multiple sclerosis: case report and review of the literature. NDT Plus. 2009;2(6):466–468. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfp113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crispin JC, Diaz-Jouanen E. Systemic lupus erythematosus induced by therapy with interferon-beta in a patient with multiple sclerosis. Lupus. 2005;14(6):495–496. doi: 10.1191/0961203305lu2147xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ubara Y, Hara S, Takedatu H, et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with beta-interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nephron. 1998;80(1):107–108. doi: 10.1159/000045147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrera WG, Balizet LB, Harberts SW, et al. Occurrence of a TTP-like syndrome in two women receiving beta interferon therapy for relapsing multiple sclerosis [American Academy of Neurology 51st annual meeting. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. April 17–24, 1999. Abstracts]; Neurology; 1999. p. A135. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Broughton A, Cosyns JP, Jadoul M. Thrombotic microangiopathy induced by long-term interferon-β therapy for multiple sclerosis: a case report. Clin Nephrol. 2011;76(5):396–400. doi: 10.5414/cn106523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olea T, Díaz-Mancebo R, Picazo ML, Martínez-Ara J, Robles A, Selgas R. Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with use of interferon-beta. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2012;5:97–100. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S30194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]