Abstract

Recent sequencing studies of clear cell (conventional) renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) have identified inactivating point mutations in the chromatin-modifying genes PBRM1, KDM6A/UTX, KDM5C/JARID1C, SETD2, MLL2 and BAP1. To investigate whether aberrant hypermethylation is a mechanism of inactivation of these tumor suppressor genes in ccRCC, we sequenced the promoter region within a bona fide CpG island of PBRM1, KDM6A, SETD2 and BAP1 in bisulfite-modified DNA of a representative series of 50 primary ccRCC, 4 normal renal parenchyma specimens and 5 RCC cell lines. We also interrogated the promoter methylation status of KDM5C and ARID1A in the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) ccRCC Infinium data set. PBRM1, KDM6A, SETD2 and BAP1 were unmethylated in all tumor and normal specimens. KDM5C and ARID1A were unmethylated in the TCGA 219 ccRCC and 119 adjacent normal specimens. Aberrant promoter hypermethylation of PBRM1, BAP1 and the other chromatin-modifying genes examined here is therefore absent or rare in ccRCC.

Keywords: PBRM1, BAP1, SETD2, KDM6A, KDM5C, MLL2, ARID1A, renal cell carcinoma, clear cell RCC, promoter methylation

Introduction

Several tumor suppressor genes predisposing to inherited forms of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) have been identified1 but, until recently, with the exception of VHL, few classical tumor suppressor genes inactivated by point mutation had been identified in sporadic RCC, which is 96% of the disease.2 A large scale systematic re-sequencing study,3 three exome sequencing studies,4-6 as well as an exome sequencing study of chromosome 3p genes7 in clear cell (conventional) RCC (ccRCC) have identified several novel genes with inactivating point mutations, indicative of a tumor suppressor function. Many of these genes are involved in chromatin modification. The PBRM1 gene, which codes for the BAF180 subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, was reported to have point mutation in 41% of ccRCC6 and is the second most frequently mutated gene in ccRCC. The same study reported missense mutation of ARID1A, which codes for a different subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex, in two of seven RCC exomes sequenced.6 ARID1A is inactivated by a truncating point mutation in clear cell and endometrioid ovarian cancer,8,9 as well as in bladder10 and other cancers.11 The KDM6A and KDM5C genes, which encode enzymes that demethylate, and the SETD2 and MLL2 genes, which methylate important lysine residues of histone H3, each showed point mutations in 3% of ccRCCs.3 Point mutation of KDM6A12 and MLL213-16 has been reported in other cancer types. The BAP1 gene is a component of the ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis pathway (UMPP) and shows mainly inactivating point mutations in 8–14% of ccRCC.4,5,7 Somatic mutation of BAP1 is also present in melanoma17 and mesothelioma.18 Among other functions,19 BAP1 modifies chromatin by mediating deubiquitination of histone H2A, although this may not be the main mechanism of tumor suppression in RCC.5

Aberrant hypermethylation of the core promoter region within a CpG island is associated with loss of transcription of classical tumor suppressor genes in cancer.20,21 Hypermethylation is an alternative to point mutation or deletion for inactivation of one allele of the gene. Since several previously identified classical tumor suppressor genes, such as VHL,22-24 CDKN2A/p16INK4a,23,25 CDH1/E-cadherin23,26 and SDHB,27 are known to be hypermethylated in subsets of sporadic ccRCC, the recently identified tumor suppressor genes involved in chromatin modification might also be inactivated by aberrant promoter hypermethylation with the associated loss of mRNA expression in RCC. Immunohistochemical staining (IHC) studies have shown that most ccRCC negative by IHC for PBRM1 or BAP1 have an inactivating point mutation. There were no cases of point mutation or indels as the second inactivation event.5 The known high frequency of LOH of 3p28 likely accounts for the second hit in many tumors with point mutation but this has not been studied yet. Aberrant promoter hypermethylation may therefore be the method of inactivation in the subset of 10–12% ccRCC negative by IHC for PBRM1 or BAP15 that show no evidence of point mutation and, also, for the inactivation of the second allele in some tumors with point mutation.

Knowledge of whether hypermethylation is a mechanism of inactivation of a particular tumor suppressor gene is important: (1) for an accurate assessment of the frequency of inactivation of the gene, which would indicate the relative importance of specific pathways and networks and, thereby, their biological significance in a specific disease; (2) for identification of molecular subtypes within a tumor type;29-32 (3) to determine the utility of a gene as a marker of diagnosis, prognosis or chemoresponse33,34 and; (4) to understand the potential of the gene or protein as a therapeutic target, including for epigenetic drugs.35

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) uses the Illumina Infinium platform for global CpG methylation profiling and data from ccRCC are available for web-based analysis. However, the Infinium HumanMethylation27 probes for PBRM1, KDM6A, SETD2 and BAP1 are located outside the promoter CpG island by both the more stringent Takai and Jones criteria36 and the more relaxed definition of a CpG island that Infinium uses.37 In general, CpG loci outside CpG islands are susceptible to methylation in normal cells and provide little or no information as to the mRNA expression status of a gene. In contrast, methylation of CpG loci within a bona fide CpG island, particularly near the transcriptional start site (TSS), is associated with loss of transcription, and thereby allelic inactivation, in classical tumor suppressor genes.20,21 Promoter CpG islands are generally unmethylated in the corresponding normal cell of origin. To determine if the chromatin modifying genes found to have point mutation3-7 are also inactivated by promoter hypermethylation in ccRCC, we examined the methylation status of CpG loci near the TSS in a bona fide CpG island by sequencing bisulfite-modified DNA of 50 representative ccRCC for PBRM1, KDM6A, SETD2 and BAP1 or by interrogation of the TCGA RCC data set for the KDM5C and ARID1A genes where the Infinium probe(s) are located within the bona fide CpG island of the promoter region. Here, we demonstrate that aberrant promoter methylation of PBRM1 and other chromatin modifying genes is absent or rare in ccRCC.

Results and Discussion

PBRM1, KDM6A, SETD2 and BAP1 have a bona fide CpG island in the promoter region

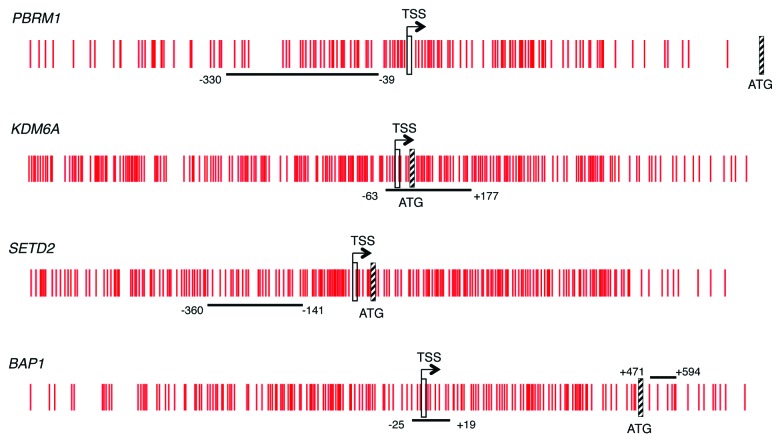

To determine the methylation status of PBRM1 and other chromatin-modifying genes in ccRCC, we first investigated whether these genes had a bona fide CpG island, according to the more stringent criteria of Takai and Jones, i.e., lower limits of 500 bp for length, 55% for GC content and 0.65 for ObsCpG/ExpCpG36 in the promoter region. Analysis of gene sequence in Ensembl showed that the promoter region of all the genes but one was within a bona fide CpG island. The promoter region of MLL2 did not contain a bona fide CpG island so MLL2 was not further examined. The Infinium HumanMethylation27 annotation (available at ftp://ftp.illumina.com/Methylation/InfiniumMethylation/HumanMethylation27/) used the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) relaxed definition of 200 bp length, 50% GC content and 0.6 ObsCpG/ExpCpG for identification of CpG islands in genes in the Consensus Coding Sequence (CCDS) database.37 We obtained the sequence of the probe(s) from the TCGA Infinium HumanMethylation27 BeadChip annotation in order to determine the position of the probe(s) within the gene (Table 1). While all the genes identified with inactivating point mutation are included in the Infinium HumanMethylation27 BeadChip, the probe(s) for PBRM1, KDM6A or SETD2 are not located within a CpG island of either definition, presumably because of sequence-dependent features of the BeadChip chemistry.37 One of two Infinium probes for BAP1 was not located in the CpG island while the other probe was from the 5′ end of the island but relatively distant (1230bp) from the TSS (Table 1). We therefore designed primers for direct bisulfite sequencing or pyrosequencing of a region of the bona fide CpG island near the TSS using the Ensembl annotation of the TSS as nucleotide -1 of the 5′ UTR for PBRM1, KDM6A, SETD2 and BAP1 (Fig. 1). Methylation that surrounds the TSS is strongly linked with transcriptional silencing.20,21 The 1000 bp of sequence centered on the TSS was generally unmethylated in a survey of human genes in 12 normal tissues.38 No Alu or other repetitive elements were detected in the amplicons to be sequenced.

Table 1. Information on the CpG loci interrogated for each gene.

| Gene name | Chromo-somal location | Bona fide CpG island | # of Infinium probes and location relative to CpG island | Amplification and Sequencing Primers / Infinium Probes | CpGs read out of total number of CpGs in amplicon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PBRM1 |

3p21 |

Yes |

1; outside |

F – TGGTGGTTGTAGTAATTTTTAGA R - GAGGGGTAAGGGAGGTGAG |

23/29 |

|

KDM6A |

Xp11 |

Yes |

1; outside |

F – GATAAAGTTGGTGTGTTGGTTT R – TAGTTTGATAGTRGAGGAGAG |

21/28 |

|

SETD2 |

3p21 |

Yes |

2; outside |

F – GGTTTATTGTTTYGGAGAGTTAT R - TGAGGGTGAGAGGGAGAGA |

|

|

BAP1 |

3p21 |

Yes |

1; outside |

assay #ADS1756FS1, EpigenDX |

7/7 |

| |

|

|

1; within |

F- GATGAATAAGGGTTGGTTGGAGT R – GTTTGTTTGATTATTATTTTTTTTTTTTG PSQ - TGGTTGGAGTTGGAGA |

3/6 |

|

KDM5C |

Xp11 |

Yes |

1; within |

cg04927982_CGTGCACCGCCGGTCCATCCGGAAAGACGATCCGGCAAACTAATTACAAT |

6 |

|

ARID1A |

1p36 |

Yes |

2; within |

cg11856093_CAGGCCAGGGCTTTGTTGTCCGCCATGTTGTTGGTGGAAGACGGCGGCCG |

4 |

| |

|

|

|

cg17385674_ACCCTCTTTGCAAGCCCGAAAGAATGACTGATCATTGTTCAGACGATTCG |

3 |

| MLL2 | 12q13 | No | 1 | cg13007988_CGGGGAGACCTGTTGGTGCCAAGAAAGAGATCTATATGCCTACTAAGTCT | 1 |

Gene name according to NCBI; chromosomal location according to NCBI; CpG island according to Takai and Jones criteria by CpG Island Searcher; number of probes in Infinium humanmethylation27 beadchip and position of probe relative to Takai and Jones CpG island; sequence of primers used and Infinium probes examined in our study, Y and R indicate degenerate T or C in forward and reverse primer respectively, primer sequences for the most 5′ area of BAP1 are proprietary and available as a commercial kit (Epigen DX, Hopkinton, MA, USA); number of CpG loci read from total number of CpG loci in amplicon due to loss of sequence read at the 5′ end of the bisulfite sequencing amplicon or the 3′ end of the pyrosequencing amplicon.

Figure 1. CpG island schematic of the genes studied. Vertical red lines represent individual CpG loci in the island. The TSS is indicated by a vertical rectangle and the ATG by a hatched box. The horizontal black line indicates the area sequenced and the nucleotide position given is relative to the location of the TSS from Ensembl.

The promoter CpG islands of PBRM1, KDM6A, SETD2 and BAP1 are unmethylated in ccRCC

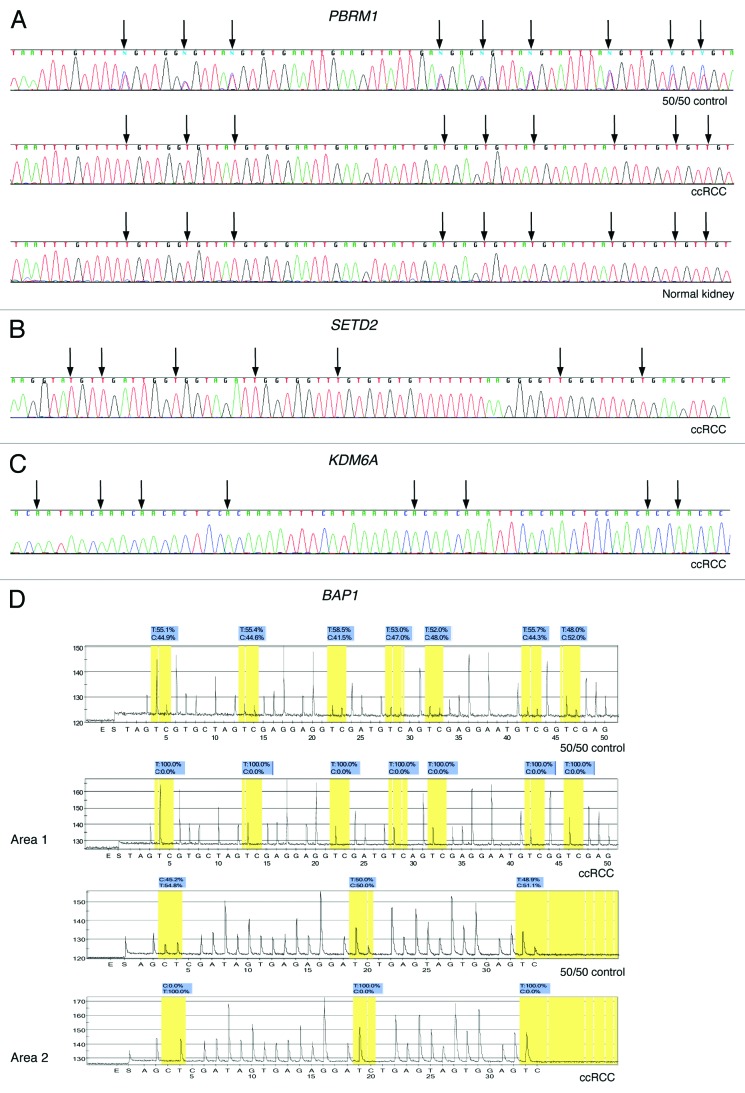

The 50 ccRCC, 4 normal renal parenchyma and 5 RCC cell lines were unmethylated for PBRM1, KDM6A and SETD2 by direct bisulfite sequencing and unmethylated for BAP1 by pyrosequencing (Fig. 2). Because pyrosequencing provides a shorter sequence read-length we also examined a second area of the BAP1 promoter CpG island (Table 1). The 50:50 unmethylated:fully methylated DNA control showed approximately 50% methylation for PBRM1 and BAP1 (Fig. 2) and a bias toward the methylated template DNA for KDM6A and SETD2 (data not shown). Both KDM6A and KDM5C are located on the X chromosome and known to escape X-inactivation.39,40 Therefore, both alleles of KDM6A and KDM5C would be expected to be unmethylated in normal cells, as we observed (data not shown). There is little evidence for mutational inactivation of PBRM1 and the other chromatin-modifying genes in non-ccRCC. No point mutation of PBRM1 was found in 36 non-ccRCC6 and none of SETD2 and KDM5C in 65 non-ccRCC.3 Point mutation of KDM6A was reported in 1 of 5 papillary RCC3 and is found in types of cancer other than RCC.12 The BAP1 gene has not yet been examined for point mutation by sequencing in non-ccRCC. Consequently, we only examined the methylation status of these genes in a small number of non-ccRCC. We found PBRM1, KDM6A, SETD2 and BAP1 to be unmethylated in five papillary RCC and five chromophobe RCC.

Figure 2. Representative examples of bisulfite sequencing and pyrosequencing. (A) Bisulfite direct sequencing of PBRM1 in 50:50 unmethylated:fully methylated DNA control, a ccRCC and normal renal parenchyma. Methylation is visible as a cytosine peak superimposed on a thymine peak at CpG loci indicated by black arrows in the 50:50 control. (B) Bisulfite direct sequencing of the reverse strand of KDM6A in ccRCC. (C) Bisulfite direct sequencing of SETD2 in a ccRCC. (D) Bisulfite pyrosequencing of two areas of the BAP1 promoter CpG island in the 50:50 control and a ccRCC.

The promoter CpG islands of KDM5C and ARID1A are unmethylated in the TCGA ccRCC data set

The Infinium probe for KDM5C is located within a bona fide CpG island and -49bp upstream of the TSS. The two Infinium probes for ARID1A are both located within a bona fide CpG island 821 bp upstream and 863 bp downstream of the TSS. We examined the raw β-value (methylation score) of the probes for these two genes in the available TCGA data set of 219 ccRCC compared with 119 matched adjacent normal renal tissue samples for evidence of aberrant hypermethylation in ccRCC. We considered a probe unmethylated if the β-value was ≤ 0.15 and hypermethylated if the individual tumor had a β-value at least 0.2 higher than the β-value of the matched normal sample.37 By these criteria, there was no evidence of hypermethylation of the Infinium probe for KDM5C or the two ARID1A Infinium probes in the 219 TCGA ccRCC.

Considerations of the RCC specimen set and methylation assays

The 50 ccRCC screened for methylation status in our study are broadly representative of the disease.41 They comprise 25 low grade (I or II) of mainly 4 cm or under in size (stage I) and organ-confined (stage I or II) as well as 25, mainly high grade (III or IV), stage III or IV tumors (Table 2). A representative specimen set is important as the presence of an alteration may be associated with a particular pathologic subset as for example in a recent study that reported a significant correlation between BAP1 point mutation and high grade ccRCC while PBRM1 point mutation was associated with low grade ccRCC.5

Table 2. Clinicopathological data for the 50 ccRCC.

| ccRCC | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade I |

3 |

|

|

|

| Grade II |

20 |

|

2 |

|

| Grade III |

4 |

1 |

3 |

8 |

| Grade IV | 9 |

That all 50 ccRCC specimens were determined by a pathologist to have ≥ 70% tumor cell content means that the sensitivity of detection of hypermethylation should not be overly diluted by unmethylated alleles from the normal cells that contaminate the tumor specimen. The TCGA ccRCC specimens are also assessed for adequate tumor cell content and 12% of 219 ccRCC showed VHL hypermethylation (β-value > 0.15), a frequency expected from prior studies.22-24 A conservative estimate of the typical minimal sensitivity of detection of methylation by the relevant assays might be 20% for direct bisulfite sequencing,42 10% for pyrosequencing42 and 15% for Infinium analysis.37 While we observed evidence of amplification43 or sequencing bias, as assessed by inclusion of a 50% unmethylated normal DNA:50% fully methylated DNA control, for KDM6A and SETD2 this would not lead to underscoring of aberrant methylation. We prefer direct sequencing, as performed here, to subcloning of a mixed population of alleles in order to avoid potential cloning efficiency bias44 and artifact.45

The 50 ccRCC studied here were obtained as a single biopsy from surgical resection, either radical or partial nephrectomy, performed pre-treatment. Since the entire tumor mass was not sampled, intratumor heterogeneity of an alteration could potentially result in an underestimate of methylation. However, in a recent study of intratumor heterogeneity, PBRM1 point mutation was considered ubiquitous, while point mutation of both SETD2 and KDM5C was shared, in multiple biopsies from the primary RCC in individuals with metastatic RCC (KDM6A, BAP1 or ARID1A point mutation were not present in the 4 RCC in the study).46 Furthermore, point mutation of PBRM1 and the other chromatin-modifying genes was originally identified by sequencing of a single biopsy from each of several ccRCC.3-7 This suggests that if methylation of any of these genes was moderately frequent in ccRCC it would have likely been detected in the single biopsy from one or more of the 50 ccRCC examined by us or of the 219 ccRCC examined by TCGA.

The entire promoter CpG island of each gene was not assayed in this study. However, in our experience47,48 and that of others49,50 with bisulfite sequencing, the majority of individual CpG loci in the island, particularly within 500 bp of the TSS, are methylated in tumor suppressor genes that are aberrantly hypermethylated in cancer cells. In addition, in the human genome, there is evidence for significant correlation of co-methylation of CpG sites over distances shorter than or equal to 1000 bp.38,51,52 Therefore, we believe the number of CpG loci interrogated for methylation status by sequencing near to the TSS in our study is sufficient to identify the presence of aberrant promoter hypermethylation. Similarly, it should be noted that the TCGA ccRCC Infinium BeadChip data for KDM5C and ARID1A are based on a more limited number of CpG loci, that the two ARID1A probes are located relatively distant (> 500 bp) to the TSS, and that we did not verify the Infinium probe methylation status by another technology, e.g., sequencing or quantitative methylation-specific PCR (qMSP). Taken together, the points considered above suggest that aberrant promoter hypermethylation of PBRM1, BAP1 and the other chromatin-modifying genes examined here is absent or rare in ccRCC.

Why is hypermethylation of PBRM1 and other genes uncommon in ccRCC?

The location of VHL, PBRM1, SETD2 and BAP1 on chromosomal arm 3p means that a large deletion of 3p could result in simultaneous inactivation of one allele of all four genes in a single mutation event. In terms of conferring a growth advantage to a tumor cell, such a deletion event might be favored over hypermethylation of an allele of one of the four genes. A similar advantage has been postulated as a reason why homozygous deletion around CDKN2A at 9p21 that results in simultaneous inactivation of the INK4A and ARF tumor suppressors is more frequent than CDKN2A point mutation or hypermethylation in human cancer.53 However, the known hypermethylation of VHL in ~10–15% of sporadic ccRCC22-24 argues against this idea, although the relative timing of inactivation of VHL to inactivation of PBRM1, SETD2 and BAP1 in the initiation and development of ccRCC needs to be considered. A related point is that it has been noted54 and remains unclear why some classical tumor suppressor genes that contain a bona fide CpG island in the promoter region are susceptible to aberrant hypermethylation, i.e., BRCA1 and MLH1, while others are not, i.e., BRCA2 and MSH2, since transcriptional silencing of any of these genes would be predicted to provide a growth advantage to a tumor cell. Lastly, it is possible that other mechanisms of epigenetic silencing, i.e., dysregulation of miRNA expression,55,56 aberrant methylation of an upstream regulatory gene,47 or histone modification in the absence of hypermethylation,57 act upon PBRM1 and the other tumor suppressor genes found to be unmethylated in our study.

Conclusions

Information on whether a tumor suppressor gene is hypermethylated is important to determine the relative contribution of the gene to the disease, to discover molecular subtypes and to assess its utility as a diagnostic, prognostic or chemoresponse marker as well as its potential as a therapeutic target. To our knowledge, this report is the first to examine the methylation status of the promoter of these genes identified by inactivating point mutation as important in the biology of RCC. We conclude that aberrant promoter hypermethylation of PBRM1, BAP1, SETD2, KDM6A and the other chromatin-modifying genes examined here is absent or rare in ccRCC.

Materials and Methods

Specimen Preparation

The FCCC Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study and all patients provided written consent. Fifty fresh-frozen ccRCC and four normal renal parenchyma from patients with no history of RCC and of similar age (mean 66 y) to the average age of diagnosis of RCC (64 y) from 2005–2009 (http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/kidrp.html) were obtained from the Fox Chase Cancer Center (FCCC) Biospecimen Repository. A piece of each RCC embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound was examined under a microscope with the assistance of a pathologist (ED) to identify an area with a tumor cell content ≥ 70% to be dissected out for DNA isolation by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation.58 The normal renal parenchyma specimens were similarly examined and determined to be non-neoplastic before DNA isolation. Clinicopathological data for the 50 ccRCC were obtained from the FCCC Kidney Keystone Database. The tumor set comprised 33 males and 17 females ranging from 33–85 y of age, with a median of 59 y, at diagnosis. The Fuhrman nuclear grade and clinical stage of the ccRCC are presented in Table 2. The ccRCC cell lines 786–0, 769-P, A498 and papillary RCC cell line ACHN were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The ccRCC cell line Caki-1 was obtained from the National Cancer Institute-Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis (NCI-DCTD) Tumor Cell Line Repository (NCI) and was originally described by Foch and Trempe.59

Infinium humanmethylation27 annotation and TCGA ccRCC data

The localization of the Infinium HumanMethylation27 probe sequence (available at ) relative to the TSS and bona fide CpG island was examined for each gene in Ensembl (www.ensembl.org). Amplification and sequencing primers were designed to examine an area of sequence within 500 bp upstream or downstream of the TSS predicted by Ensembl in a CpG island that fulfilled the widely used definition criteria of Gardiner-Garden and Frommer60 as well as the modifications suggested by Takai and Jones36 using CpG Island Searcher (http://cpgislands.usc.edu/). The presence of Alu and other repetitive elements was examined by repeatmasker v3.3.0 (http://repeatmasker.org). Primer sequences are given in Table 2. We accessed the TCGA ccRCC raw data available at https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/tcgaCancerDetails.jsp?diseaseType=KIRC&diseaseName=Kidney%20renal%20clear%20cell%20carcinoma on September 12, 2012. The raw β-value from 219 ccRCC and 119 adjacent normal renal parenchyma run on the Infinium humanmethylation27 BeadChip was examined to assess the methylation status for the relevant gene probes.

Bisulfite modification, PCR and sequencing of DNA

One microgram of specimen DNA was bisulfite modified using the EZ-DNA Methylation kit (Zymo Research Corporation) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Approximately 100 ng of bisulfite-modified DNA was used as template for PCR amplification with the primers given in Table 1. The PCR product was run on a 1.5% agarose gel alongside a molecular weight marker, cut out and purified by the Qiaquick MinElute Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) then sequenced on an ABI 3130 sequencer. For BAP1, one primer was biotinylated before PCR amplification and the PCR product purified as above. Each amplicon was sequenced on a Pyrosequencing PSQ 96MA genetic analysis system using the Pyro Gold Reagent Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). A 50:50 mix of unmethylated DNA/M.SssI in vitro methylated DNA was run to control for amplification43 or sequencing bias for each gene analyzed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kirill Yudin for writing script to generate the schematic of CpG islands in Figure 1, Emmanuelle Nicolas PhD, Genetic Research Facility at FCCC, for design and optimization of BAP1 pyrosequencing, Suraj Peri PhD, Department of Biostatistics at FCCC for help with TSS data in Ensembl and Andrew Kossenkov PhD, Director of Bioinformatics at the Wistar Institute, Philadelphia for help with the interrogation of TCGA data. This publication was supported in part by grant number P30 CA006927 from the National Cancer Institute. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. Additional funds were provided by Fox Chase Cancer Center via institutional support of the Kidney Keystone Program.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/epigenetics/article/24552

References

- 1.Linehan WM, Srinivasan R, Schmidt LS. The genetic basis of kidney cancer: a metabolic disease. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:277–85. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavlovich CP, Schmidt LS. Searching for the hereditary causes of renal-cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:381–93. doi: 10.1038/nrc1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalgliesh GL, Furge K, Greenman C, Chen L, Bignell G, Butler A, et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 2010;463:360–3. doi: 10.1038/nature08672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo G, Gui Y, Gao S, Tang A, Hu X, Huang Y, et al. Frequent mutations of genes encoding ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis pathway components in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:17–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peña-Llopis S, Vega-Rubín-de-Celis S, Liao A, Leng N, Pavía-Jiménez A, Wang S, et al. BAP1 loss defines a new class of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:751–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varela I, Tarpey P, Raine K, Huang D, Ong CK, Stephens P, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene PBRM1 in renal carcinoma. Nature. 2011;469:539–42. doi: 10.1038/nature09639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duns G, Hofstra RM, Sietzema JG, Hollema H, van Duivenbode I, Kuik A, et al. Targeted exome sequencing in clear cell renal cell carcinoma tumors suggests aberrant chromatin regulation as a crucial step in ccRCC development. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:1059–62. doi: 10.1002/humu.22090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones S, Wang TL, Shih IeM, Mao TL, Nakayama K, Roden R, et al. Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling gene ARID1A in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Science. 2010;330:228–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1196333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiegand KC, Shah SP, Al-Agha OM, Zhao Y, Tse K, Zeng T, et al. ARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1532–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gui Y, Guo G, Huang Y, Hu X, Tang A, Gao S, et al. Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling genes in transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Nat Genet. 2011;43:875–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones S, Li M, Parsons DW, Zhang X, Wesseling J, Kristel P, et al. Somatic mutations in the chromatin remodeling gene ARID1A occur in several tumor types. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:100–3. doi: 10.1002/humu.21633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Haaften G, Dalgliesh GL, Davies H, Chen L, Bignell G, Greenman C, et al. Somatic mutations of the histone H3K27 demethylase gene UTX in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2009;41:521–3. doi: 10.1038/ng.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones DT, Jäger N, Kool M, Zichner T, Hutter B, Sultan M, et al. Dissecting the genomic complexity underlying medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012;488:100–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lohr JG, Stojanov P, Lawrence MS, Auclair D, Chapuy B, Sougnez C, et al. Discovery and prioritization of somatic mutations in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) by whole-exome sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:3879–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121343109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, Mungall AJ, Goya R, Mungall KL, Corbett RD, et al. Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nature. 2011;476:298–303. doi: 10.1038/nature10351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pugh TJ, Weeraratne SD, Archer TC, Pomeranz Krummel DA, Auclair D, Bochicchio J, et al. Medulloblastoma exome sequencing uncovers subtype-specific somatic mutations. Nature. 2012;488:106–10. doi: 10.1038/nature11329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harbour JW, Onken MD, Roberson ED, Duan S, Cao L, Worley LA, et al. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science. 2010;330:1410–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1194472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bott M, Brevet M, Taylor BS, Shimizu S, Ito T, Wang L, et al. The nuclear deubiquitinase BAP1 is commonly inactivated by somatic mutations and 3p21.1 losses in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Nat Genet. 2011;43:668–72. doi: 10.1038/ng.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White AE, Harper JW. Cancer. Emerging anatomy of the BAP1 tumor suppressor system. Science. 2012;337:1463–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1228463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1148–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smits KM, Schouten LJ, van Dijk BA, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa CA, Wouters KA, Oosterwijk E, et al. Genetic and epigenetic alterations in the von hippel-lindau gene: the influence on renal cancer prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:782–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dulaimi E, Ibanez de Caceres I, Uzzo RG, Al-Saleem T, Greenberg RE, Polascik TJ, et al. Promoter hypermethylation profile of kidney cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3972–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herman JG, Latif F, Weng Y, Lerman MI, Zbar B, Liu S, et al. Silencing of the VHL tumor-suppressor gene by DNA methylation in renal carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9700–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herman JG, Merlo A, Mao L, Lapidus RG, Issa JP, Davidson NE, et al. Inactivation of the CDKN2/p16/MTS1 gene is frequently associated with aberrant DNA methylation in all common human cancers. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4525–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costa VL, Henrique R, Ribeiro FR, Pinto M, Oliveira J, Lobo F, et al. Quantitative promoter methylation analysis of multiple cancer-related genes in renal cell tumors. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:133. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris MR, Hesson LB, Wagner KJ, Morgan NV, Astuti D, Lees RD, et al. Multigene methylation analysis of Wilms’ tumour and adult renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:6794–801. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beroukhim R, Brunet JP, Di Napoli A, Mertz KD, Seeley A, Pires MM, et al. Patterns of gene expression and copy-number alterations in von-hippel lindau disease-associated and sporadic clear cell carcinoma of the kidney. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4674–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cunningham JM, Christensen ER, Tester DJ, Kim CY, Roche PC, Burgart LJ, et al. Hypermethylation of the hMLH1 promoter in colon cancer with microsatellite instability. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3455–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herman JG, Umar A, Polyak K, Graff JR, Ahuja N, Issa JP, et al. Incidence and functional consequences of hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation in colorectal carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6870–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kane MF, Loda M, Gaida GM, Lipman J, Mishra R, Goldman H, et al. Methylation of the hMLH1 promoter correlates with lack of expression of hMLH1 in sporadic colon tumors and mismatch repair-defective human tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57:808–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veigl ML, Kasturi L, Olechnowicz J, Ma AH, Lutterbaugh JD, Periyasamy S, et al. Biallelic inactivation of hMLH1 by epigenetic gene silencing, a novel mechanism causing human MSI cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8698–702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cairns P. Gene methylation and early detection of genitourinary cancer: the road ahead. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:531–43. doi: 10.1038/nrc2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maradeo ME, Cairns P. Translational application of epigenetic alterations: ovarian cancer as a model. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2112–20. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Issa JP, Kantarjian HM. Targeting DNA methylation. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3938–46. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takai D, Jones PA. Comprehensive analysis of CpG islands in human chromosomes 21 and 22. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3740–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052410099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bibikova M, Le J, Barnes B, Saedinia-Melnyk S, Zhou L, Shen R, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling using Infinium® assay. Epigenomics. 2009;1:177–200. doi: 10.2217/epi.09.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eckhardt F, Lewin J, Cortese R, Rakyan VK, Attwood J, Burger M, et al. DNA methylation profiling of human chromosomes 6, 20 and 22. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1378–85. doi: 10.1038/ng1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenfield A, Carrel L, Pennisi D, Philippe C, Quaderi N, Siggers P, et al. The UTX gene escapes X inactivation in mice and humans. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:737–42. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.4.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsuchiya KD, Greally JM, Yi Y, Noel KP, Truong JP, Disteche CM. Comparative sequence and x-inactivation analyses of a domain of escape in human xp11.2 and the conserved segment in mouse. Genome Res. 2004;14:1275–84. doi: 10.1101/gr.2575904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hock LM, Lynch J, Balaji KC. Increasing incidence of all stages of kidney cancer in the last 2 decades in the United States: an analysis of surveillance, epidemiology and end results program data. J Urol. 2002;167:57–60. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)65382-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clark SJ, Statham A, Stirzaker C, Molloy PL, Frommer M. DNA methylation: bisulphite modification and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2353–64. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Warnecke PM, Stirzaker C, Melki JR, Millar DS, Paul CL, Clark SJ. Detection and measurement of PCR bias in quantitative methylation analysis of bisulphite-treated DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4422–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.21.4422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grunau C, Clark SJ, Rosenthal A. Bisulfite genomic sequencing: systematic investigation of critical experimental parameters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:E65–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.13.e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sandovici I, Leppert M, Hawk PR, Suarez A, Linares Y, Sapienza C. Familial aggregation of abnormal methylation of parental alleles at the IGF2/H19 and IGF2R differentially methylated regions. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1569–78. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ibanez de Caceres I, Dulaimi E, Hoffman AM, Al-Saleem T, Uzzo RG, Cairns P. Identification of novel target genes by an epigenetic reactivation screen of renal cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5021–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ibragimova I, Ibáñez de Cáceres I, Hoffman AM, Potapova A, Dulaimi E, Al-Saleem T, et al. Global reactivation of epigenetically silenced genes in prostate cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:1084–92. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Millar DS, Ow KK, Paul CL, Russell PJ, Molloy PL, Clark SJ. Detailed methylation analysis of the glutathione S-transferase pi (GSTP1) gene in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 1999;18:1313–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stirzaker C, Millar DS, Paul CL, Warnecke PM, Harrison J, Vincent PC, et al. Extensive DNA methylation spanning the Rb promoter in retinoblastoma tumors. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2229–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barrera V, Peinado MA. Evaluation of single CpG sites as proxies of CpG island methylation states at the genome scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:11490–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Y, Zhu J, Tian G, Li N, Li Q, Ye M, et al. The DNA methylome of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jen J, Harper JW, Bigner SH, Bigner DD, Papadopoulos N, Markowitz S, et al. Deletion of p16 and p15 genes in brain tumors. Cancer Res. 1994;54:6353–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Esteller M. CpG island hypermethylation and tumor suppressor genes: a booming present, a brighter future. Oncogene. 2002;21:5427–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huse JT, Brennan C, Hambardzumyan D, Wee B, Pena J, Rouhanifard SH, et al. The PTEN-regulating microRNA miR-26a is amplified in high-grade glioma and facilitates gliomagenesis in vivo. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1327–37. doi: 10.1101/gad.1777409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meng F, Henson R, Wehbe-Janek H, Ghoshal K, Jacob ST, Patel T. MicroRNA-21 regulates expression of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in human hepatocellular cancer. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:647–58. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richon VM, Sandhoff TW, Rifkind RA, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitor selectively induces p21WAF1 expression and gene-associated histone acetylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10014–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180316197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning. A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Foch JaT. G. Chapter 5: New Human Tumor Cell Lines In: Foch J, ed. Human Tumor Cells in Vitro. New York and London: Plenum Press, 1975:115-59. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gardiner-Garden M, Frommer M. CpG islands in vertebrate genomes. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:261–82. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fuhrman SA, Lasky LC, Limas C. Prognostic significance of morphologic parameters in renal cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6:655–63. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A III. Chapter 43 Kidney. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual Seventh Edition 2009:479-90. [Google Scholar]