Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Haemobilia is a rare complication of acute cholecystitis and may present as upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

We describe two patients with acute cholecystitis presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to haemobilia. Bleeding from the duodenal papilla was seen at endoscopy in one case but none in the other. CT demonstrated acute cholecystitis with a pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery in both cases. Definitive control of intracholecystic bleeding was achieved in both cases by embolisation of the cystic artery. Both patients remain symptom free. One had subsequent laparoscopic cholecystostomy and the other no surgery.

DISCUSSION

Pseudoaneurysms of the cystic artery are uncommon in the setting of acute cholecystitis. OGD and CT angiography play a key role in diagnosis. Transarterial embolisation (TAE) is effective in controlling bleeding. TAE followed by interval cholecystectomy remains the treatment of choice in surgically fit patients.

CONCLUSION

We highlight an unusual cause of upper GI haemorrhage. Surgeons need to be aware of this rare complication of acute cholecystitis. Immediate non-surgical management in these cases proved to be safe and effective.

Keywords: Haemobilia, Pseudoaneurysm, Cholecystitis, Transarterial embolisation, Upper GI bleeding

1. Introduction

Haemobilia is a rare complication of acute cholecystitis. This occurs when there is a communication between the vascular system and the biliary tree. 22 cases of pseudoaneurysms of the cystic artery as the cause have been described.1 Only 2 cases of bleeding from a normal cystic artery have been reported.2,3 We present two cases of upper GI bleeding secondary to acute cholecystitis with bleeding from the cystic artery and describe the non-surgical management of this entity.

2. Presentation of case 1

A 74-year-old gentleman was admitted with a 3-week history of worsening epigastric pain associated with a bout of haematemesis that morning. On general examination, he was jaundiced and tachycardic (100 beats per minute) with blood pressure of 134/86. Abdominal examination was unremarkable.

Initial blood tests demonstrated a normocytic anaemia with haemoglobin 11.7 g/dL (previously 13.2), leucocytosis and deranged liver function tests. Bilirubin was 57 μmol/L (0–22), Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) 561 IU/L (38–126), Alanine Transaminase (ALT) 258 IU/L (0–55) and Aspartate transaminase (AST) 246 IU/L (0–45). Albumin, total protein and INR were normal.

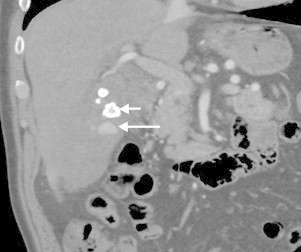

Fluid resuscitation with intravenous crystalloid and 2 units of blood was initiated and parenteral proton pump inhibitors (PPI) started. Oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (OGD) revealed normal mucosal lining of the oesophagus, stomach and pylorus. Fresh blood and clot was seen throughout the duodenum with fresh blood emerging from the duodenal papilla. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) revealed an ill-defined thick-walled gall bladder containing several stones with localised extravasation of contrast from the cystic artery into a pseudoaneurysm in the gallbladder (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Coronal CT in arterial phase of contrast enhancement showing gallstone (short arrow) and contrast extravasation in to the gallbladder (long arrow).

We proceeded directly to transarterial embolisation. From a transfemoral approach the cystic artery was catheterized with a microcatheter. Contrast extravasation was demonstrated and the cystic artery was embolised with two 2 mm platinum coils (Figs. 2 and 3). This stopped the bleeding immediately and the patient was discharged 2 days later and placed on the waiting list for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. He was readmitted 17 days later with another attack of acute cholecystitis with normal liver function tests. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was attempted but dissection of the gallbladder was difficult due to a firmly adherent inflammatory omental mass. Due to the risk of visceral and vascular injury, a laparoscopic cholecystostomy was performed. The patient was discharged after 5 days of antibiotics with no drain. At 6 weeks’ outpatient follow-up, the decision was made for conservative management as long as he remains asymptomatic.

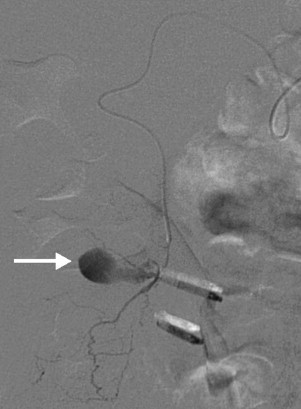

Fig. 2.

Selective catheterization of branch of cystic artery that had been in spasm showing extravasation into the gallbladder (arrow).

Fig. 3.

Coils occluding the bleeding branch and main trunk of cystic artery (arrow).

3. Presentation of case 2

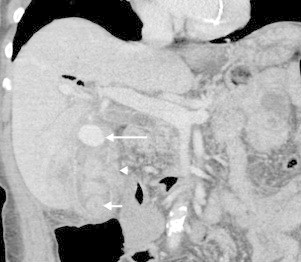

A 79-year old lady was admitted with a 3-week history of melaena and weight loss. On examination she was pale and jaundiced, tachycardic (110 beats per minute) and hypotensive (96/58). Abdominal examination revealed mild right upper quadrant tenderness and dark blood on digital rectal examination. Blood tests revealed a normocytic anaemia, 6.8 g/dL and obstructive jaundice: Bilirubin was 42 μmol/L (0–22), ALP 1962 IU/L (38–126), AST 638 IU/L (0–45) and ALT 319 IU/L (0–55). Following blood transfusions and parenteral PPI, she underwent an OGD that showed blood within the duodenum but no bleeding point. CT revealed a 25 × 17 × 20 mm false aneurysm arising from the cystic artery, an ill defined gallbladder with thickened walls, multiple gallstones and pneumobilia (which remained unexplained) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Coronal CT in arterial phase showing pseudoaneurysm (long arrow), thickened gallbladder wall (arrowhead) and gallstones (medium arrow).

From a transfemoral approach the cystic artery supplying the pseudoaneurysm was selectively catheterised with a microcatheter and successfully embolised using three 2 mm platinum coils (Fig. 5). CT 3 months later demonstrated resolution of the pseudoaneurysm, resolving cholecystitis and no gallstones. Given her past medical history of hypertension and advanced chronic obstructive airway disease requiring supplemental home oxygen, she was deemed an unsuitable surgical candidate hence was managed conservatively. She remains asymptomatic on outpatient review.

Fig. 5.

Selective angiogram of hepatic artery showing pseudoaneurysm arising from a branch of the cystic artery (arrow).

4. Discussion

Haemobilia, defined as blood in the biliary tree, was first described by Sandblom in 1948 as a consequence of trauma to the liver.4 It presents with Quinke's classic triad of symptoms: upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage, upper abdominal pain and jaundice. The triad occurs in only 22% of cases5 as patients rarely present with upper GI bleeding,6 therefore requiring a high index of suspicion for diagnosis.

With the advent of invasive percutaneous interventions such as liver biopsy, iatrogenic injury accounts for two-thirds of the cases of haemobilia.7 Non-traumatic causes include inflammation, malignancy and congenital or acquired vascular malformations. Despite the high incidence of acute cholecystitis, haemobilia is rare because the inflammation results in early thrombosis of the cystic artery. Occasionally, this perivascular inflammation causes thrombosis of the vasa recta and damages the adventitia of the artery.8 This damages the integrity of the arterial walls making them prone to bleeding, resulting in haematomas outside the vessel, walled off by surrounding tissues i.e. a pseudoaneurysm. Pseudoaneurysms may also occur as a direct result of trauma during or after laparoscopic cholecystectomy,7 biliary stents and warfarin overdose.9 60% of pseudoaneurysms involve the right hepatic artery, 30% the common hepatic and only 10% the cystic artery.10

A history of haematemesis or melaena should prompt an OGD which in 60% of cases will show active bleeding or clot from the duodenal papilla.6 This can also occur with a bleed into the main pancreatic duct, called haemosuccus pancreaticus.11 If a pseudoaneurysm is suspected, ultrasonography with colour Doppler or digital subtraction angiography can identify the source, however, contrast enhanced CT is the modality of choice as it will accurately confirm the diagnosis.12

Minimally invasive, non-operative management has a lower morbidity and mortality than operative management.13,14 Trans-arterial embolisation with coils is effective in controlling haemobilia and thus stabilising patients’ clinical state. It allows diagnostic evaluation of variants of the vascular anatomy and therapeutic intervention with a success rate of 80–100%.2,11,12

Due to the risk of recurrence or gallbladder ischaemia after cystic artery embolisation subsequent cholecystectomy should be considered.9 The timing depends on the patient's symptoms and fitness for surgery. Surgery can potentially be a difficult procedure depending on the inflammation and adherence of the gallbladder, increasing the risk of visceral injury.

5. Conclusion

Haemobilia is a rare complication of acute cholecystitis as there is often early thrombosis of the cystic artery secondary to inflammation. We present 2 cases of acute cholecystitis both with Quinke's triad as a result of bleeding from a pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery in the gallbladder. After diagnosis with CT both patients were successfully treated by transarterial embolisation. Currently transarterial embolisation followed by interval cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice in patients fit enough for surgery.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case series and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contributions

Mr Nana drafted and wrote the paper with contributions and critical analysis from all three co-authors.

Dr Gibson and Dr Spiers performed the radiological interventions while Mr Ramus was involved in the surgical management. All authors have read and approved the final article.

We thank Drs N. Chandra and M. Myszor for the endoscopic findings in both patients.

References

- 1.Komatsu Y., Orita H., Sakurada M., Maekawa H., Hoppo T., Sato K. Report of a case: Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery with hemobilia treated by arterial embolization. Journal of Medical Cases. 2011;2(4):178–183. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Ishay O., Farraj M., Shmulevsky P., Person B., Kluger Y. Gallbladder ulcer erosion into the cystic artery: a rare cause of upper gastro-intestinal bleeding case report. World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 2010;5(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Contini S., Uccelli M., Sassatelli R., Pinna F., Corradi D. Gallbladder ulcer eroding the cystic artery: a rare cause of hemobilia. American Journal of Surgery. 2009 Aug;198(2):e17–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandblom P. Hemorrhage into the biliary tract following trauma; traumatic hemobilia. Surgery. 1948 Sep;24(3):571–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quinke H. Ein fall von aneurysma der leberarterie. Klinische Wochenschrift. 1871;8:349–351. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saluja S.S., Ray S., Gulati M.S., Pal S., Sahni P., Chattopadhyay T.K. Acute cholecystitis with massive upper gastrointestinal bleed: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterology. 2007;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green M.H., Duell R.M., Johnson C.D., Jamieson N.V. Haemobilia. British Journal of Surgery. 2001 Jun;88(6):773–786. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akatsu T., Tanabe M., Shimizu T. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery secondary to cholecystitis as a cause of hemobilia: report of a case. Surgery Today. 2007;37(5):412–417. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srinivasaiah N., Bhojak M., Jackson R., Woodcock S. Vascular emergencies in cholelithiasis and cholecystectomy: our experience with two cases and literature review. Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International. 2008;7(2):217–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sansonna F., Boati S., Sguinzi R., Migliorisi C., Pugliese F., Pugliese R. Severe hemobilia from hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm. Case Reports in Gastrointestinal Medicine. 2011;2011:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2011/925142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vimalraj V., Kannan D.G., Sukumar R. Haemosuccus pancreaticus: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11(June (4)):345–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00063.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desai A.U., Saunders M.P., Anderson H.J., Howlett D.C. Successful transcatheter arterial embolisation of a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to calculus cholecystitis: a case report. Journal of Radiology Case Reports. 2010;4(2):18–22. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v4i2.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srivastava D.N., Sharma S., Pal S. Transcatheter arterial embolization in the management of hemobilia. Abdominal Imaging. 2006;31(August (4)):439–448. doi: 10.1007/s00261-005-0392-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moodley J., Singh B., Lalloo S., Pershad S., Robbs J.V. Non-operative management of haemobilia. British Journal of Surgery. 2001;88(August (8)):1073–1076. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]