Abstract

Calocybe indica, a tropical edible mushroom, is popular because it has good nutritive value and it can be cultivated commercially. The current investigation was undertaken to determine a suitable substrate and the appropriate thickness of casing materials for the cultivation of C. indica. Optimum mycelial growth was observed in coconut coir substrate. Primordia initiation with the different substrates and casing materials was observed between the 13th and 19th day. The maximum length of stalk was recorded from sugarcane leaf, while diameter of stalk and pileus, and thickness of pileus were found in rice straw substrate. The highest biological and economic yield, and biological efficiency were also obtained in the rice straw substrate. Cow dung and loamy soil, farm-yard manure, loamy soil and sand, and spent oyster mushroom substrates were used as casing materials to evaluate the yield and yield-contributing characteristics of C. indica. The results indicate that the number of effective fruiting bodies, the biological and economic yield, and the biological efficiency were statistically similar all of the casing materials used. The maximum biological efficiency was found in the cow dung and loamy soil casing material. The cow dung and loamy soil (3 cm thick) was the best casing material and the rice straw was the best substrate for the commercial cultivation of C. indica.

Keywords: Biological efficiency, Calocybe indica, Casing material, Spawn, Substrate, Yield

Calocybe indica, commonly known as milky white mushroom, grows during the summer in the gangetic plain of Bangladesh and West Bengal of India [1]. This mushroom is a relatively new introduction from India [2]. Its robust size, sustainable yield, attractive color, delicacy, long shelf-life, and lucrative market value have attracted the attention of both mushroom consumers and prospective growers [3]. C. indica is rich in protein, lipids, fiber, carbohydrates, and vitamins and contains an abundant amount of essential amino acids [4].

A substrate is an important substance for growing mushrooms. Usually, a wide range of diverse cellulosic substrates are used for cultivating mushrooms. Volvariella volvacea is grown on banana leaves, bracts of pineapple, coconut coir, coffee bran, coffee pulp, corn cob, corn stover, orange peel, rice bran, rice straw, sisal bagasse, sugarcane bagasse, and wheat straw [5]. Various agricultural byproducts are being used as substrates for the cultivation of oyster mushrooms, including banana leaves, peanut hull, corn leaves, mango fruits and seeds, sugarcane leaves, and wheat and rice straw [6]. In Asia, rice straw is widely used as the substrate for cultivating oyster mushroom [7] and is also considered the best substrate for yield and high protein content. Wheat straw is commonly used as a substrate in Europe and sawdust is commonly used as a substrate in Southeast Asian countries for the cultivation of oyster mushrooms.

The production and marketing potential of the milky white mushroom in Bangladesh is promising. Because of the high local demand for and export potential of this mushroom, many private entrepreneurs are interested in its commercial cultivation. This mushroom requires a temperature of 30~35℃ and a relative humidity of 70~80% for cultivation, which is conducive to the environmental conditions of Bangladesh [8]. Huge quantities of lignocellulosic residues such as rice straw, wheat straw, mustard straw, maize straw, waste cotton, water hyacinth, sugarcane bagasse, coconut coir, and kash are generated annually through activities of the agricultural, forest, and food-processing industries in Bangladesh. About 30 million tons of rice straw is produced annually in Bangladesh [9], which might prove suitable for mushroom cultivation. Therefore, the present investigation was undertaken to determine the best substrates and casing materials with appropriate thickness for the commercial cultivation of C. indica.

Materials and Methods

Mushroom strain and substrates

C. indica was obtained from the National Mushroom Development and Extension Centre (NAMDEC), Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Coconut coir (Cocos nucifera), kash (Saccharum spontanum), maize straw (Zea mays), rice straw (Oryza sativa), sugarcane bagasse, sugarcane leaf (Saccharum officinarum), and waste cotton (Gossypium indicum) were used as substrates in this study.

Preparation of spawn

The substrates were chopped into 3~4 inch lengths. On a dry-weight basis, 0.2% CaCO3 and 30% wheat bran were added to the chopped substrates and mixed thoroughly. Water was added to constitute a moisture level of 65%. Substrate (500 g) was added to polypropylene bags (7 × 10" sizes), and the openings of the bags were plugged with cotton and secured with plastic rings. The bags were autoclaved at 121℃ at 15 psi for 1 hr, after which they were inoculated with 2 teaspoons of a mother culture of C. indica. The spawn packet was kept in a dark room for incubation at 30~32℃ for approximately 30 to 35 days.

Casing materials and experimental conditions

Cow dung and loamy soil (3 : 1, v/v), farm-yard manure, loamy soil and sand (3 : 1, v/v), and spent oyster mushroom substrate (saw dust) were used as casing materials, which were collected from the NAMDEC farm. All casing materials were sterilized at 65℃ for 4 hr. After mycelial colonization, the mouth of the spawn packet was covered with casing materials and maintained with five different (1 to 5 cm) levels of thickness. It was then transferred to the culture house and maintained at a temperature of 30~35℃ and a relative humidity of 70~80%.

Experimental design

The experiment had a completely randomized design with four replications. The following data were collected: mycelial growth in the spawn, the number of days required for the initiation of primordia, the number of days required for total harvest, length and diameter of the stalk, the diameter and thickness of the pileus, the number of effective fruiting bodies, biological yield, economic yield, and biological efficiency. The data were analyzed according to standard methods using the MSTAT-C program. Means were compared using Duncan's multiple range test. Biological efficiency was measured using the following formula:

Biological efficiency (%) = total biological yield/total substrate used × 100

Results and Discussion

Effect of different substrates on yield and yield-contributing characteristics

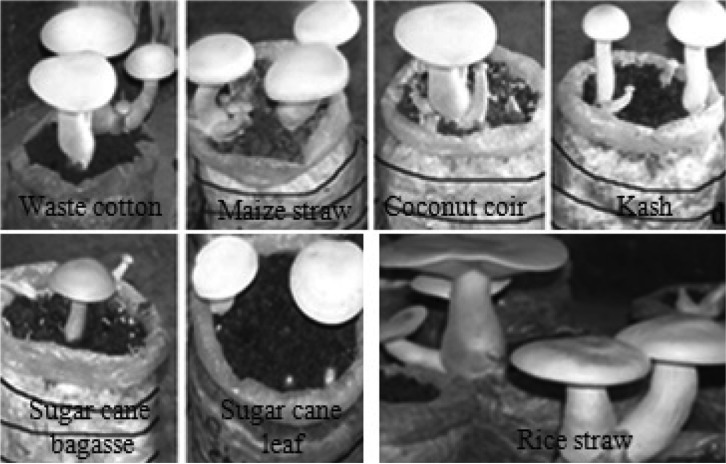

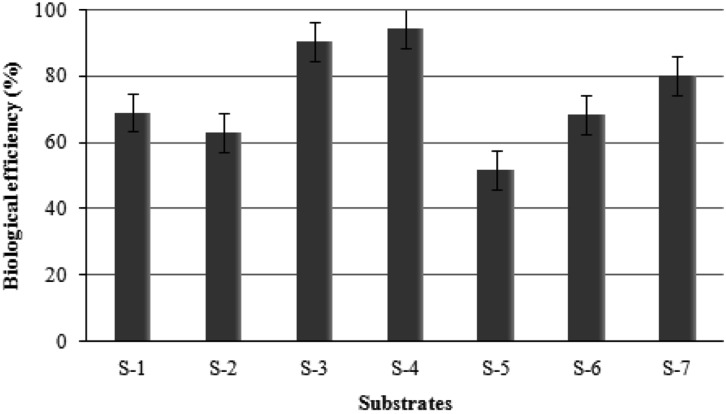

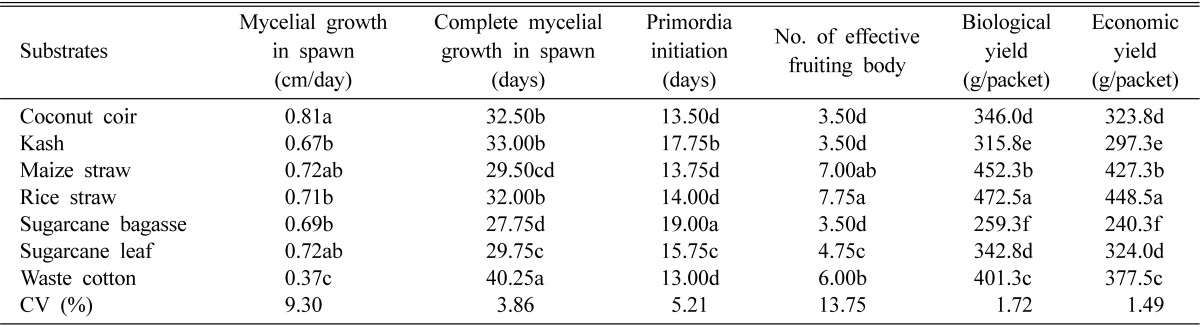

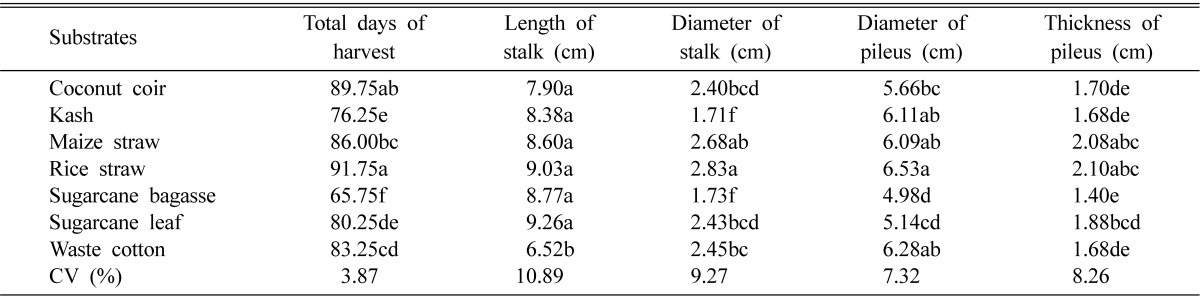

The optimum mycelial growth in the spawn packet was observed in the coconut coir substrate (0.81 cm), which was statistically similar to that in the maize straw and sugarcane leaf substrates. The lowest level of mycelial growth was found in the waste cotton substrate (0.37 cm). The shortest time required to complete mycelial growth was observed in the sugarcane bagasse substrate (27.75 days), followed by the maize straw (29.50 days) and sugarcane leaf (29.75 days) substrates. The longest time (40.25 days) required to complete mycelial growth was observed in the waste cotton substrate (Table 1). These findings are similar to those of previous studies using C. indica [10]. The presence of the right proportion of α-cellulose, hemi-cellulose, pectin, and lignin was the probable cause of the higher rate of mycelium in the coconut coir substrate. A suitable ratio of carbon to nitrogen might have been responsible for the higher mycelial growth. The capacity of mushrooms to grow on lingo-cellulosic substrates is related to the vigor of their mycelium [11]. The minimum time for primordia initiation was observed in waste cotton substrate (13.0 days), which was statistically similar to that of the coconut coir, maize straw, and rice straw substrates. The longest time was recorded in sugarcane bagasse substrate (19.00 days). Patra and Pani [12] reported that the time required for primordia initiation of C. indica on paddy straw was 13~16 days. Similar findings were also reported by Jiskani et al. [13]. Substrates containing glucose, fructose, and trehalose produced the highest number of primordia, whereas abnormal fruiting bodies were produced in glycerol, xylose, sucrose, and fructose. The optimal fruiting body production occurred on glucose and fructose containing substrates [14]. Fruiting bodies of C. indica were formed in six different substrates (Fig. 1). The maximum biological and economic yield was obtained from rice straw substrate (472.5 and 448.5 g). The lowest biological and economic yields (259.3 and 240.3 g) were obtained from sugarcane bagasse (Table 1). Of all the substrates tested, the total length of harvesting time varied from 65.75 to 91.75 days. The longest time for harvesting was observed in rice straw substrate (Table 2). The maximum diameter of stalk and pileus and thickness of pileus were also obtained from rice straw. Statistically similar stalk lengths were found in all of the substrates. The minimum diameter (4.98 cm) and thickness (1.40 cm) of pileus was observed in sugarcane bagasse (Table 2). Biological efficiency varied significantly between the substrates. The highest (91.75%) and lowest (51.86%) biological efficiencies were observed in the rice straw and sugarcane bagasse substrates, respectively (Fig. 2). The findings of the present study are comparable with those of previous studies using C. indica [15, 16]. Rice straw was the best substrate, followed by wheat straw. Therefore, cellulose-rich organic substrates are suitable for cultivating mushrooms [17, 18].

Table 1.

Effect of different substrates on the mycelial growth, fruiting body formation, and yield of Calocybe indica

In a column the same letters indicate that the values are not significantly different by Duncan's multiple range test (P > 0.05). CV, coefficient of variation.

Fig. 1.

The fruiting body of Calocybe indica produced in different substrates.

Table 2.

Effect of different substrates on the yield-contributing characteristics of Calocybe indica

In a column the same letters indicate that the values are not significantly different by Duncan's multiple range test (P > 0.05). CV, coefficient of variation.

Fig. 2.

Effect of different substrates on the biological efficiency of Calocybe indica. The vertical bars represent the standard error. S-1, coconut coir; S-2, kash; S-3, maize straw; S-4, rice straw; S-5, sugarcane bagasse; S-6, sugarcane leaf; S-7, waste cotton.

Effect of different casing materials and thicknesses on yield and yield-contributing characteristics

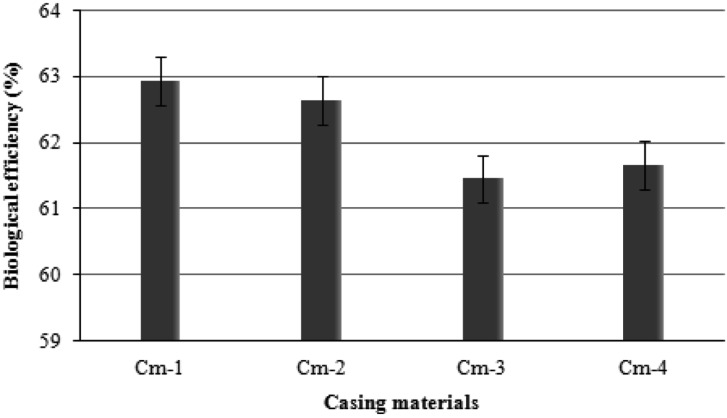

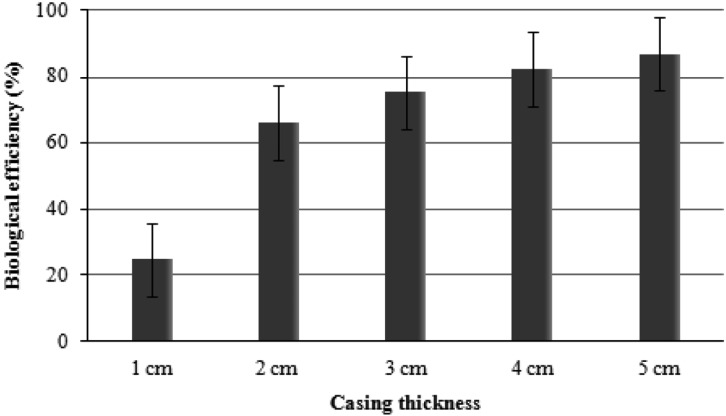

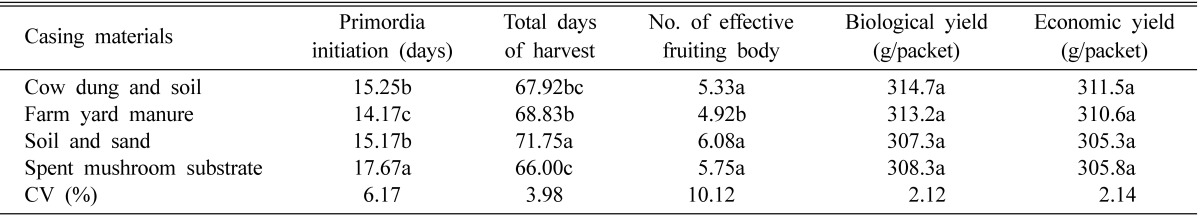

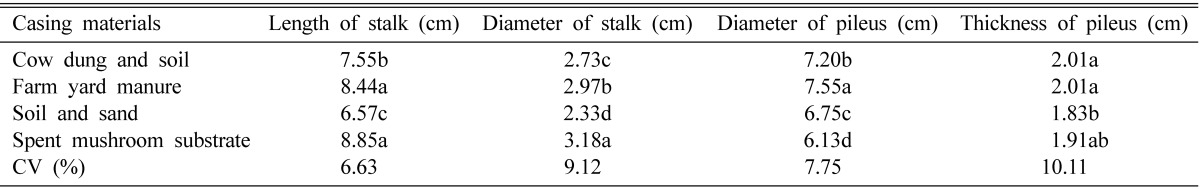

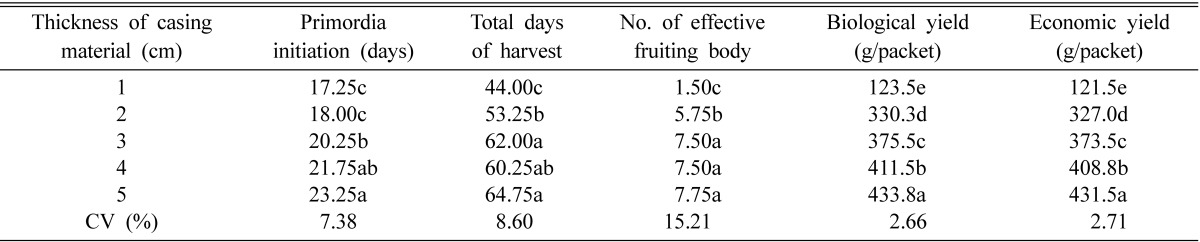

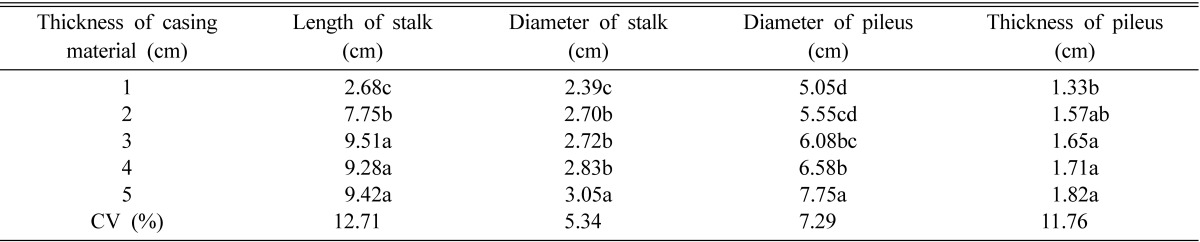

Cow dung and loamy soil, farm-yard manure, loamy soil and sand, and spent oyster mushroom substrate were used as casing materials to evaluate the yield and yield-contributing characteristics of C. indica. The results indicate that the number of effective fruiting bodies, the biological and economic yields, and biological efficiency were statistically similar in all of the casing materials tested. Maximum biological efficiency was recorded in cow dung and soil (62.94%) followed by the farm-yard manure (62.64%), spent mushroom substrate (61.66%), and soil and sand (61.46%) casing materials (Fig. 3). Primordia initiation occurred earlier in farm-yard manure than in the other casing materials (Table 3). The greatest stalk length and diameter were observed with the spent mushroom substrate casing material. The maximum diameter and thickness of pileus were found with the farm-yard manure (Table 4). These findings are comparable with data from a study using Agaricus bisporus, because it grows well in composting casing materials [19]. The effects of five different thicknesses of cow dung and loamy soil as casing materials on the yield and yield-contributing characteristics of C. indica are presented in Tables 5 and 6. The results indicate that 3 to 5 cm thicknesses of casing materials had significant positive results on the number of days required for primordia initiation, the total number of days to harvest, the number of effective fruiting bodies, biological and economic yields, stalk length and diameter, and diameter and thickness of pileus. The highest and lowest biological efficiencies were 5 cm (86.76%) and 1 cm (24.7%), respectively (Fig. 4). The casing layer is an essential component for the artificial cultivation of C. indica. According to Sassine et al. [20], the casing layer must be very loose; otherwise, the primordia cannot penetrate from the bottom to the top of the casing layer. The 3 cm casing layer thickness seemed to be the most efficient. The combination of composted cow dung and loamy soil proved to be a good casing material, which likely played a role in stimulating the initiation of the fruiting body [21-23]. Thus, the 3 cm thick composting cow dung and loamy soil was the best casing material and the rice straw was the best substrate for the commercial cultivation of C. indica.

Fig. 3.

Effect of different casing materials on the biological efficiency of Calocybe indica. The vertical bars represent the standard error. Cm-1, cow dung and soil; Cm-2, farm-yard manure; Cm-3, soil and sand; Cm-4, spent mushroom substrate.

Table 3.

Effect of different casing materials on fruiting body formation and the yield of Calocybe indica

In a column the same letters indicate that the values are not significantly different by Duncan's multiple range test (P > 0.05). CV, coefficient of variation.

Table 4.

Effect of different casing materials on the yield-contributing characteristics of Calocybe indica

In a column the same letters indicate that the values are not significantly different by Duncan's multiple range test (P > 0.05). CV, coefficient of variation.

Table 5.

Effect of different thicknesses of casing materials on the fruiting body formation and yield of Calocybe indica

In a column the same letters indicate that the values are not significantly different by Duncan's multiple range test (P > 0.05). CV, coefficient of variation.

Table 6.

Effect of different thicknesses of casing materials on the yield-contributing characteristics of Calocybe indica

In a column the same letters indicate that the values are not significantly different by Duncan's multiple range test (P > 0.05). CV, coefficient of variation.

Fig. 4.

Effect of different thicknesses of casing materials on the biological efficiency of Calocybe indica. The vertical bars represent the standard error.

References

- 1.Chakravarty DK, Sarkar BB, Kundu BM. Cultivation of Calocybe indica, a tropical edible mushroom. Curr Sci. 1981;50:550. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Purkayastha RP, Chandra A. A new technique for in vitro production of Calocybe indica: an edible mushroom of India. Mush J. 1976;40:112–113. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chakraborty U, Sikdar SR. Intergeneric protoplast fusion between Calocybe indica (milky mushroom) and Pleurotus florida aids in the qualitative and quantitative improvement of sporophore of the milky mushroom. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;26:213–225. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alam N, Amin R, Khan A, Ara I, Shim MJ, Lee MW, Lee TS. Nutritional analysis of cultivated mushrooms in Bangladesh: Pleurotus ostreatus, Pleurotus sajor-caju, Pleurotus florida and Calocybe indica. Mycobiology. 2008;36:228–232. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2008.36.4.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ukoima HN, Ogbonnaya LO, Arikpo GE, Ikpe FN. Cultivation of mushroom (Volvariella volvacea) on various farm wastes in Obubra local government of Cross River state, Nigeria. Pak J Nutr. 2009;8:1059–1061. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cangy C, Peerally A. Studies of Pleurotus production on sugarcane bagasse. Afr J Mycol Biotechnol. 1995;3:67–79. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas GV, Prabhu SR, Reeny MZ, Bopaiah BM. Evaluation of lignocellulosic biomass from coconut palm as substrate for cultivation of Pleurotus sajor-caju (Fr.) Singer. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;14:879–882. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishnamoorthy AS, Muthuswamy MT, Nakkeeran S. Technique for commercial production of milky mushroom Calocybe indica P&C. Indian J Mush. 2000;18:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amin SMR, Nirod CS, Moonmoon M, Khandaker J, Rahman M. Officer's training manual. National mushroom development and extension centre. Dhaka: Saver; 2007. pp. 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tandon G, Sharma VP. Yield performance of Calocybe indica on various substrates and supplements. Mush Res. 2006;15:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Permana IG, Meulen-ter U, Zadrazil F. Cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus and Lentinus edodes on lignocellolosic substrates for human food and animal feed production. J Agric Rural Dev Trop Subtrop. 2004;80:137–143. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patra AK, Pani BK. Yield response of different species of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus) to paddy straw. Curr Agric Res. 1995;8(Suppl):11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiskani MM, Pathan MA, Wagan KH. Yield performance of oyster mushroom Pleurotus florida (strain PK, 401) on different substrates. Pak J Agric Agric Engg Vet Sci. 1999;15:26–29. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashrafuzzaman M, Kamruzzaman AK, Ismail MR, Shahidullah SM, Fakir SA. Substrate affects growth and yield of shiitake mushroom. Afr J Biotechnol. 2009;8:2999–3006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eswaran A, Thomas S. Effect of various substrates and additives on sporophores yield of Calocybe indica and Pleurotus species. Indian J Mush. 2003;21:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doshi A, Sindana N, Chakravarti BP. Cultivation of summer mushroom Calocybe indica Purkayastha and Chandra in Rajasthan. Mush Sci. 1989;12:395–399. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhary K, Mittal SL, Tauro P. Control of cellulose hydrolysis by fungi. Biotechnol Lett. 1985;7:455–456. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quimio TH. Introducing Pleurotus flabellatus for your dinner table. Mush J. 1987;69:282–283. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandey M, Singh K, Shukla HP. The effect of different casing materials on yield of button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) Progress Agric. 2004;4:71–72. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sassine YN, Ghora Y, Kharrat M, Bohme M, Abdel-Mawgoud AMR. Waste paper as an alternative for casing soil in mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) production. J Appl Sci Res. 2005;1:277–284. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes WA. Interaction between compost and casing soil substrates in the culture of Agaricus bisporus. Mush J. 1985;151:281–288. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gülser C, Pekşen A. Using tea waste as a new casing material in mushroom (Agaricus bisporus (L.) Sing.) cultivation. Bioresour Technol. 2003;88:153–156. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8524(02)00279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colak M. Temperature profiles of Agaricus bisporus in composting stages and effects of different composts formulas and casing materials on yield. Afr J Biotechnol. 2004;3:456–462. [Google Scholar]