Abstract

Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 (BMPR2 ) gene mutations are a major risk factor for heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension (HPAH), an autosomal dominant fatal disease. We have previously shown that BMPR2 transcripts that contain premature termination codon (PTC) mutations are rapidly and nearly completely degraded through nonsense mediated decay (NMD). Here we report a unique PTC mutation (W13X) that did not behave in the predicted manner. We found that patient-derived cultured lymphocytes (CLs) contained readily detectable levels of the PTC-containing transcript. Further analysis suggested that this transcript escaped NMD by translational re-initiation at a downstream Kozak sequence, resulting in the omission of 173 amino acids. Treatment of CLs containing the PTC with an aminoglycoside decreased the truncated protein levels, with a reciprocal increase in full-length BMPR2 protein and, importantly, BMPR-II signaling. This is the first demonstration of aminoglycoside-mediated ‘repair’ of a BMPR2 mutation at the protein level in patient-derived cells and has obvious implications for treatment of HPAH where no disease-specific treatment options are available. Our data also suggest the need for a more thorough characterization of mutations prior to labeling them as haploinsufficient or dominant negative based simply on sequencing data.

Keywords: BMPR2, gentamicin, HPAH, NMD, nonsense mediated decay, premature termination codon, PTC, pulmonary hypertension, translational read-through

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a progressive, fatal disease characterized by vascular remodeling of the small pulmonary arteries, which results in increased vascular resistance and subsequent right heart failure (1, 2). PAH can be heritable or idiopathic; the conditions are similar clinically and pathologically. Heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension (HPAH) has an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance with reduced penetrance and variable age of onset (3). Mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 (BMPR2 ) gene, a member of the transforming growth factor (TGF-β) superfamily, are found in the majority of cases of HPAH and in 10–25% of those with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) and constitute the largest known risk for the development of HPAH (4–6).

The functional impact of BMPR2 mutations in HPAH has been incompletely investigated to date, with variable consequences for signaling activity reported (7). RNA studies have shown that some BMPR2 mutations produce stable transcripts; others contain premature termination codons (PTC) and are rapidly degraded through nonsense mediated decay (NMD) (8), which is an mRNA surveillance system that degrades transcripts containing PTCs to prevent translation of truncated transcripts (9, 10). The result is haploinsufficiency due to inadequate levels of normal protein (which is produced by only the wild-type allele) and, in some cases, a less severe phenotype than mutations that produce stable transcripts (11). Failure to eliminate PTC-containing transcripts can result in synthesis of abnormal proteins that can be toxic to cells through dominant negative (DN) or gain of function effects. Thus, individuals with HPAH and NMD-causing BMPR2 mutations have disease due to haploinsufficiency, whereas patients whose mutations do not cause NMD may have disease due to a DN mechanism.

Traditionally, if molecular testing identifies a mutation that results in a PTC, that patient is presumed to have PAH due to haploinsufficiency rather than due to a DN effect. This distinction is important because DN mutations may have an earlier age at diagnosis (Austin, et al., manuscript in review 2009).

Aminoglycoside antibiotics allow translational read-through by insertion of an amino acid at the PTC [for review see (12)]. This read-through function of aminoglycosides does not typically affect normal translation because of the presence of upstream and downstream regulatory sequences around a normal termination codon that ensure optimal efficiency of termination (13). The potential of aminoglycoside treatment to functionally eliminate the effect of a PTC has been demonstrated in many genetic disorders, including but not limited to cystic fibrosis (14), muscular dystrophy (15) and Hurler syndrome (16). Our detection of this unique PTC mutation in the BMPR2 gene suggested the possibility that gentamicin could be used in the treatment of HPAH in patients containing specific PTC mutations.

Here we present data from an HPAH patient whose PTC mutation did not behave in the predicted manner. We show that the PTC did not cause activation of the NMD pathway. In fact, in this case it resulted in re-initiation of translation from a downstream Kozak sequence, producing a BMPR-II protein of a lower molecular weight. We further show that we can force read-through of this PTC with aminoglycoside treatment resulting in increased cellular amounts of full-length BMPR-II protein, a corresponding decrease in the mutated BMPR-II product, and, most importantly, increased BMPR-II signaling.

Materials and methods

Cultured lymphocyte generation

Lymphocytes were isolated from 2 ml of anticoagulated whole blood (collected in an ACD tube) within 48 h of collection, by layering onto Lympho Separation Medium (MP Biomedicals, Salon, Ohio, USA) and centrifuging. The lymphocytes were removed from the serum/Lympho Sep Media interface, washed in PBS and then resuspended in 6 ml Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) media [RPMI, 1 μg/ml cyclosporine, 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 3 ml Epstein–Barr virus]. Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 3–7 days, pelleted, and resuspended in 6 ml EBV media. Cells were fed every 2 days (RPMI, 1 μg/ml cyclosporine, 15% FBS), and cyclosporine was discontinued once cell growth was observed.

Cell culture

Control cultured lymphocyte (CL) cell lines were obtained from the Coriell Cell Repositories (Camden, NJ). All CL cell lines were grown in 15% FBS in RPMI 1640 with 2 mM L-Glutamine. CLs were treated with 30 μg/ml aminoglycoside solution in water for 48 h.

Puromycin incubation and RNA isolation

Previously established CL cell lines of HPAH patients were grown in RPMI 1640 containing 20% FBS, 100 μg/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in T-25 flasks. Cells were grown to approximately 1 × 106 cells/flask and incubated in the presence or absence of puromycin (100 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 16 h prior to harvesting. RNA was harvested using the RNAeasy Mini Kit including the optional DNase treatment (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA).

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of BMPR2

Approximately 3 μg of total RNA was used as a template for cDNA synthesis using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the Superscript First-Strand System (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) with an oligo-dT primer according to the manufacturer’s protocol. One-tenth of the volume of the first-strand reaction was then used as a template for PCR amplification using the forward (ATGAAAGCTC-TGCAGCTAGGTC) and reverse (ACATCTTCT-GCATGTTTAAATGATG) RT-PCR primers and the Elongase Amplification System (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The PCR reaction mixture was denatured for 30 s at 94°C, cycled 55 times (94°C, 30 s; 58°C, 30 s; 68°C, 3 min 30 s), followed by a 5-min extension at 68°C. The resulting 3,349 bp cDNA products were visualized by ethidium bromide staining on a 1% agarose gel.

DNA sequencing of RT-PCR products

Prior to sequencing, the BMPR2 RT-PCR amplification products were purified with ExoSAP-IT (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing reactions were performed using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Samples were then analyzed by capillary electrophoresis using a 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Western blot analysis

Membranes were probed with primary antibody AF811 (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN) for 1 h and with secondary antibody 111-035-003 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for an additional 1 h. Detection was done using the Immobilon Chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Millipore, Billerica, MA). β-Actin was used as a loading control. For BMPR-II signaling analysis we used phospho-Smad1/Smad5/Smad8 antibody #9511 and Smad1 antibody #9743 (both from Cell Signaling Technology).

Prediction of Kozak sequences and protein products

Kozak sequence analysis and protein size prediction were done using the tools available at the Net-Start prediction server (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetStart/) (17) and au.expasy.org/tools/protparam. html, (18) respectively.

Results and discussion

HPAH patient with a unique PTC mutation that is not subject to NMD

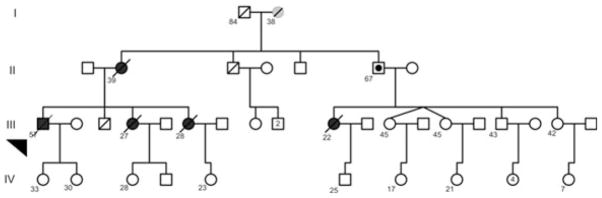

This patient was a 56-year-old previously healthy male who presented with progressive shortness of breath and exercise intolerance. His family history included multiple relatives with HPAH. Specifically, his maternal grandmother died at 38 years of age from heart failure of unknown cause, his mother was diagnosed with and died of PAH at age 35 years, and two female siblings died of PAH in the post-partum period at ages 27 and 28 (Fig. 1). His third sibling died of trauma as a young child. Finally, a female first cousin developed HPAH at age 22 and died 2 years later.

Fig. 1.

Heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension (HPAH) kindred for the patient with the W13X mutation. Boxes represent males and circles females. Solid boxes and circles indicated positive bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 (BMPR2) mutation status and disease. Solid circle in the box represent unaffected mutation carrier. Diagonal line through a box or circle represents a person who is deceased. The arrow indicates the patient analyzed in this study. Numbers adjoining symbols indicate age of the person.

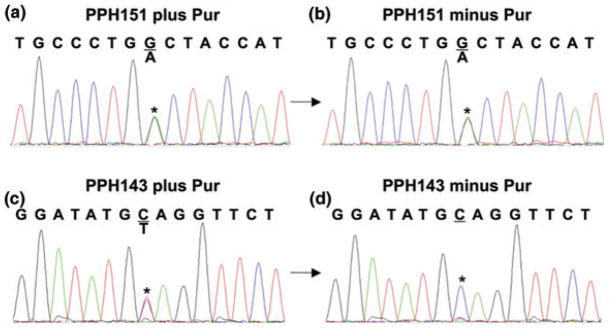

We established a CL line from the patient’s peripheral lymphocytes. These CLs were then incubated with puromycin to inhibit the activity of the NMD pathway (8). Sequence analysis of BMPR2 cDNAs generated from these puromycin treated CLs identified a heterozygous nonsense mutation (W13X) in the 13th codon of exon 1. This PTC would be predicted to activate the NMD pathway and thus give rise to a null allele (Fig. 2a) in the absence of puromycin. Surprisingly, when these CLs were grown in the absence of puromycin (resulting in normal activity of the NMD pathway), we still detected nearly equal levels of transcripts from both the normal and the PTC-containing BMPR2 alleles (Fig. 2b), compared to a control sample that contains a PTC that results in the activation of the NMD pathway (Fig. 2c,d). This suggested to us that the W13X PTC did not activate the NMD pathway as expected.

Fig. 2.

Presence of a W13X mutation that is not subject to nonsense mediated decay (NMD). (a) Heterozygous G>A (W13X) substitution in the 13th codon (TGG>TGA) detected in cDNA of cultured lymphocyte (CL) cells derived from PPH151 (proband) and incubated with puromycin to inhibit NMD. (b) Mutated transcript can still be detected in the puromycin untreated PPH151cells, suggesting that the presence of this premature termination codon (PTC) did not result in the complete degradation of the mutated transcript. Electropherograms (c) and (d) show a control CL cell line PPH143 selected for a positive NMD response secondary to being heterozygous for a different PTC gene mutation. It behaves in the expected manner and causes degradation of the transcript expressed from the mutated allele in the absence of puromycin.

The PTC results in translation re-initiation

While PTCs located more than 50 nucleotides upstream of the last exon–exon junction typically trigger NMD, exceptions to this rule have been observed in human diseases. Particularly, PTCs located in close proximity to the AUG start codon can bypass NMD by alternative translation initiation downstream of the PTC (for review see (19)).

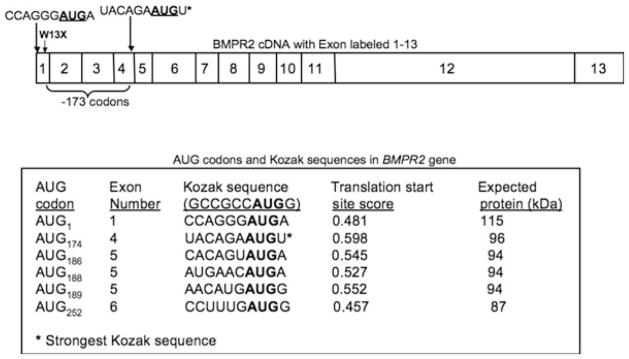

As the W13X mutation is in the first exon of the BMPR2 gene, close to the AUG start codon, this suggested to us the possibility that the escape from NMD of the mutated transcript may be due to translational re-initiation at an alternate AUG start site downstream of the W13X mutation. Optimal translation initiation in mammals conforms to an AUG codon that occurs in a robust Kozak consensus sequence (GCCRCCAUGG, where R is a purine). We thus analyzed the cDNA sequence downstream of the W13X mutation and identified 27 in-frame AUG codons. We then determined their translation initiation scores (Fig. 3) using the NetStart prediction server (17). Net-Start identified a strong Kozak sequence, stronger than the wild-type AUG sequence, in exon four of BMPR2 mRNA. The exon four AUG codon was the first start codon after the wild-type AUG codon, located 523 bp 3′ to the wild-type AUG. The predicted protein product generated (au.expasy.org/tools/protparam.html) (18) from the use of this downstream translation start site would delete ~173 amino acids, producing a truncated protein product of 96 kD compared to 115 kD for the wild-type BMPR-II protein and resulting in deletion of the ligand binding and part of the transmembrane domain of the BMPR-II.

Fig. 3.

Strong Kozak sequences are present downstream to the premature termination codon (PTC). cDNA sequence downstream of the W13X mutation was analyzed and 27 in-frame AUG codons identified (only six are shown). NetStart 1.0 was used to determine translation initiation scores for the wild-type AUG start site and the downstream AUGs. Protein size was estimated using the ProtParam tool.

Western blot analysis of cellular extracts derived from the patient’s CLs, grown in the absence of puromycin, was performed as described in the materials and methods (20). These data complemented the transcript data presented in Figure 2 and showed the presence of a full-length 113 kD BMPR-II product, as well as a much shorter 96 kD BMPR-II product (Fig. 4a lane 3). Thus, the W13X PTC did not result in the degradation of the PTC-containing transcript, but was instead translated as a truncated protein.

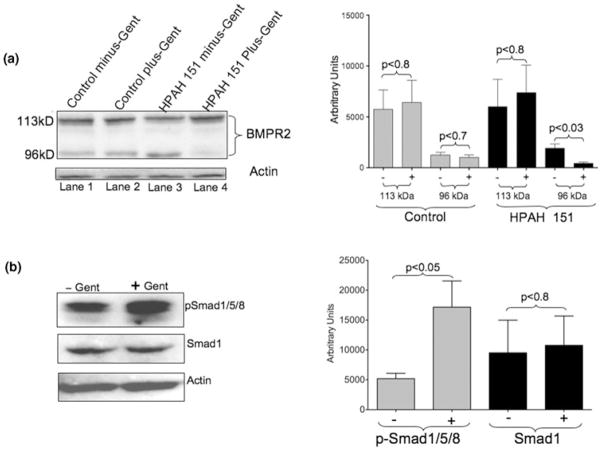

Fig. 4.

Gentamicin treatment results in a full-length bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II (BMPR2-II) product. (a) Western blot analysis in control and patient (proband)-derived cultured lymphocyte (CL) cells. The W13X mutation led to translation reinitiation downstream from the original start site. This resulted in an increased amount of a smaller (96 kD) protein product and a decreased amount of the full-length BMPR-II product (lane 3). Gentamicin treatment allowed for translational read-through of the premature termination codon (PTC), resulting in decreased 96 kD product and a corresponding increase in the full-length 115 kD product (lane 4). (b) BMPR-II signaling is also increased in the gentamicin treated CLs, derived from the proband, as shown by increased phospho-Smad1/5/8 by western blot analysis. Western blot quantification was done using ImageJ software (Collins TJ; 2007 BioTechniques 43 25–30). p values were calculated by Student’s t -test. Statistical analysis was done with Prism 5 software suite for Mac.

Aminoglycoside induces translational read-through of the PTC

As aminoglycoside (e.g., gentamicin) is known to promote translation read-through of PTCs, we next determined if we could eliminate the use of the alternative downstream translation initiation site by gentamicin-induced translation read-through of the W13X PTC. We treated W13X-containing patient-derived CLs with gentamicin and quantified BMPR-II levels by western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 4a, lanes three and four, gentamicin treatment decreased levels of the truncated (96 kD) BMPR-II product but increased full-length (113 kD) BMPR-II product levels. We then determined whether the increased full-length BMPR2 product would result in increased BMPR-II signaling in the patient-derived CLs. Gentamicin treated and untreated cells were stimulated with BMP4 (a ligand for the BMPR-II receptor) for 30 min, and BMPR-II signaling was assessed by the phosphorylation of Smad1. As shown in Figure 4b, gentamicin treatment resulted in increased signaling through the BMPR-II pathway as indicated by increased Smad1 phosphorylation. Thus, gentamicin treatment increased not only the full-length BMPR-II protein, but also signaling through the receptor.

We have recently shown that HPAH penetrance can vary with the levels of wild-type BMPR2 transcripts and that cellular levels of normal transcripts below a certain threshold can predict development of HPAH (20). The findings presented here suggest that a specific clinical approach–gentamicin-induced translational read-through–might be useful for HPAH patients carrying PTC mutations. Such increased PTC read-through might increase cellular BMPR-II levels above the threshold that determines the penetrance of HPAH as well as reduce the amount of truncated protein, which can have a DN effect. This is the first demonstration of aminoglycoside-mediated ‘repair’ of a BMPR2 mutation resulting in increased signaling in patient-derived CLs, and may have implications for treatment, as there is no disease-specific therapy for HPAH at present.

Importantly, aminoglycosides are used commonly in clinical practice to treat infections and are safe when administered by inhalation for delivery directly to the lung, which minimizes extrapulmonary effects. Chronic aminoglycoside therapy is used routinely in the care of patients with lung diseases such as cystic fibrosis. Thus, inhaled aminoglycoside therapy might be an option for safe, direct delivery to the lungs in patients with HPAH or be used as a preventative modality in those at genetic risk of disease.

It is important to note that, in patients with PTCs due to frame-shifts or alternate reading frames, treatment with aminoglycosides could allow read-through of PTCs to produce out of frame BMPR2 translational products that may be detrimental. We thus estimate that about 27% of our total kindreds could be potential candidates for augmentation with gentamicin. Our data highlight the need for more detailed characterization of patient mutations prior to labeling them as haploinsufficient or DN. Our results also complement and advance the recent findings of Nasim and colleagues, who, using HeLa cells and reporter constructs expressing beta-galactosidase, showed that gentamicin could induce translational read-through of a BMPR2 PTC (21). The obvious limitations of that study were the indirect readout of PTC read-through via reporter constructs and the use of HeLa cells. The data presented here are a more direct analysis of a unique PTC mutation analyzed in patient-derived cells.

In summary, we identified a novel BMPR2 PTC mutation (W13X) that is associated with HPAH and investigated transcript and protein expression and signaling in CLs from the affected mutation carrier. Our findings indicate that the PTC-containing transcripts are not eliminated by NMD and that their translation results in a smaller BMPR-II protein by use of an alternative translation start site downstream of the PTC. Furthermore, our data show that aminoglycoside treatment can result in read-through of the PTC (reversal of the mutation at the protein level), leading to increased expression of the full-length BMPR-II product and BMPR-II signaling. These results have implications for the treatment for HPAH, as they demonstrate for the first time that aminoglycosides could be useful in the treatment of HPAH patients with specific PTC mutations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Melissa Stauffer of Scientific Editing Solutions for her editorial help. This work was supported by P01 HL072058 and GCRC RR000095.

References

- 1.Chan SY, Loscalzo J. Pathogenic mechanisms of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:14–30. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pietra GG, Capron F, Stewart S, et al. Pathologic assessment of vasculopathies in pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:25S–32S. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman JH, Wheeler L, Lane KB, et al. Mutation in the gene for bone morphogenetic protein receptor II as a cause of primary pulmonary hypertension in a large kindred. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:319–324. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108023450502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cogan JD, Vnencak-Jones CL, Phillips JA, III, et al. Gross BMPR2 gene rearrangements constitute a new cause for primary pulmonary hypertension. Genet Med. 2005;7:169–174. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000156525.09595.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng Z, Morse JH, Slager SL, et al. Familial primary pulmonary hypertension (gene PPH1) is caused by mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein receptor-II gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:737–744. doi: 10.1086/303059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lane KB, Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, et al. The International PPH Consortium. Heterozygous germline mutations in BMPR2, encoding a TGF-beta receptor, cause familial primary pulmonary hypertension. Nat Genet. 2000;26:81–84. doi: 10.1038/79226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudarakanchana N, Flanagan JA, Chen H, et al. Functional analysis of bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor mutations underlying primary pulmonary hypertension. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1517–1525. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.13.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cogan JD, Pauciulo MW, Batchman AP, et al. High frequency of BMPR2 exonic deletions/duplications in familial pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:590–598. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-165OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez CI, Bhattacharya A, Wang W, et al. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 2001;274:15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maquat LE. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: splicing, translation and mRNP dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:89–99. doi: 10.1038/nrm1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noensie EN, Dietz HC. A strategy for disease gene identification through nonsense-mediated mRNA decay inhibition. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:434–439. doi: 10.1038/88099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linde L, Kerem B. Introducing sense into nonsense in treatments of human genetic diseases. Trends Genet. 2008;24:552–563. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Namy O, Hatin I, Rousset JP. Impact of the six nucleotides downstream of the stop codon on translation termination. EMBO Reps. 2001;2:787–793. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howard M, Frizzell RA, Bedwell DM. Aminoglycoside antibiotics restore CFTR function by overcoming premature stop mutations. Nat Med. 1996;2:467–469. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barton-Davis ER, Cordier L, Shoturma DI, et al. Aminoglycoside antibiotics restore dystrophin function to skeletal muscles of mdx mice. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:375–381. doi: 10.1172/JCI7866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keeling KM, Brooks DA, Hopwood JJ, et al. Gentamicin-mediated suppression of Hurler syndrome stop mutations restores a low level of alpha-L-iduronidase activity and reduces lysosomal glycosaminoglycan accumulation. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:291–299. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedersen AG, Nielsen H. Neural network prediction of translation initiation sites in eukaryotes: perspectives for EST and genome analysis. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1997;5:226–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, et al. The proteomics protocols handbook. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ, USA: 2005. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server; pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kochetov AV, Ahmad S, Ivanisenko V, et al. uORFs, reinitiation and alternative translation start sites in human mRNAs. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1293–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamid R, Cogan JD, Hedges LK, et al. Penetrance of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension is modulated by the expression of normal BMPR2 allele. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(4):649–54. doi: 10.1002/humu.20922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasim MT, Ghouri A, Patel B, et al. Stoichiometric imbalance in the receptor complex contributes to dysfunctional BMPR-II mediated signalling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1683–1694. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]