Abstract

Purpose

Spirituality has been associated with better cardiac autonomic balance, but its association with cardiovascular risk is not well studied. We examined whether more frequent private spiritual activity was associated with reduced cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study.

Methods

Frequency of private spiritual activity (prayer, Bible reading, and meditation) was self-reported at year 5 of follow-up. Cardiovascular outcomes were centrally adjudicated, and cardiovascular risk was estimated from proportional hazards models.

Results

Final models included 43,708 women (mean age, 68.9 ± 7.3 years; median follow-up, 7.0 years) free of cardiac disease through year 5 of follow-up. In age-adjusted models, private spiritual activity was associated with increased cardiovascular risk (hazard ratio [HR], 1.16; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02–1.31 for weekly vs. never; HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.11–1.40 for daily vs. never). In multivariate models adjusted for demographics, lifestyle, risk factors, and psychosocial factors, such association remained significant only in the group with daily activity (HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.03–1.30). Subgroup analyses indicate this association may be driven by the presence of severe chronic diseases.

Conclusions

Among aging women, higher frequency of private spiritual activity was associated with increased cardiovascular risk, likely reflecting a mobilization of spiritual resources to cope with aging and illness.

Keywords: Women’s health, Cardiovascular diseases, Spirituality

Introduction

There is increasing interest in the study of the relationship between religiosity/spirituality (R/S) and health, fostered by the finding that individuals who regularly attend religious services [1–9] have a reduction in overall mortality of almost 20%. The evidence for the possible association between R/S and reduced cardiovascular risk, however, is less consistent. Multiple prospective cohort and case-control studies [3,9–12] have linked R/S with reduced cardiovascular mortality and morbidity. A crosssectional study conducted in a rural population in India has shown that men participating in prayer and yoga had a lower prevalence of coronary heart disease after adjustment for coronary risk factors [13]. A composite R/S measure (frequency of service attendance, prayer, and fasting) was inversely associated with acute coronary events in a recent case-control study [14] conducted in a predominantly Moslem and Christian population. On the other hand, other studies somewhat contradicted these results. Schnall et al. [8] reported a lack of association between several self-reported measures of R/S (religious affiliation, frequency of service attendance, and religious coping) and cardiovascular mortality in a large population of postmenopausal women. More frequent service attendance, prayer or meditation, and higher daily spiritual experience scores were not associated with reduced cardiovascular risk in a prospective cohort study involving more than 5000 healthy men and women enrolled in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) [15]. In a study of noninstitutionalized older adults, Colantonio et al. [16] reported that more frequent worship attendance was associated with a reduced risk of stroke in unadjusted models; in adjusted models, however, this association was no longer significant. Another study conducted in myocardial infarction survivors with depression and low social support did not show an association between daily spiritual experience scores, church attendance, or frequency of private spiritual activity and nonfatal cardiac events [17].

The link between frequency of individual private spiritual practices such as prayer, meditation, and devotional reading and cardiovascular health has been less frequently investigated at the population level compared with the more public aspects of R/S, namely, religious services attendance. Practices such as prayer or meditation are particularly interesting because their association with cardiovascular risk is less likely to be affected by variables—such as social support—that are known confounders of the association between service attendance and cardiovascular outcomes. Furthermore, unlike service attendance, the physiologic changes occurring during prayer and meditation have been extensively studied and consist of a decrease in sympathetic nervous system activity, oxygen consumption, respiratory rate, and minute ventilation [18]. Prayer or mantra recitation have been linked with higher levels of cardiac autonomic control [19] and increased baroreflex sensitivity [20], conditions that in turn have been associated with a reduced risk of cardiac arrhythmias and cardiac mortality [21–23]. A reduction in the activity of the sympathetic nervous system may be beneficial for patients with coronary heart disease, as shown by findings of increased exercise tolerance and delayed onset of electrocardiographic signs of ischemia in patients enrolled in a transcendental meditation program [24]. Similar results were shown by Benson et al [25], who reported that meditation reduced the number of premature ventricular contractions in these patients.

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate whether private spiritual activity (prayer, meditation, and reading of religious literature) is associated with a reduced incidence of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events in a large population of community-dwelling postmenopausal women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Observational Study (OS). The WHI affords a unique opportunity to evaluate this association given its large sample size, as well as the adjudication of cardiovascular outcomes. Our study hypothesis was that women who report to engage in private spiritual activity, compared with women reporting no spiritual activity, would have a reduced cardiovascular risk.

The secondary aim was to assess whether the association may differ in women with a history of severe chronic diseases before the assessment of private spiritual activity compared with women without such history. This analysis was undertaken in light of the important role of R/S, including private spiritual activity, in coping with serious illness. This is illustrated by the fact that the proportion of people with serious illnesses (e.g., cancer) who report praying for their health (77%) [26] may be double the proportion in the general population (43%) [27]. Further, there is evidence [28] that the association between private spiritual activity and cardiovascular risk may differ depending on whether such activity is a longstanding, lifelong behavior or rather an episodic phenomenon elicited in response to stressful events or illness.

Despite the concerns raised in regard to the methodologic limitations and lack of direct clinical applications of the research in this field [29], the study of the role of R/S in the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) may have important public health consequences if these practices are associated with a lower cardiovascular risk [30].

Methods

The WHI included a set of randomized clinical trials and a separate OS [29]. The OS, the focus of this analysis, was a large prospective cohort study conducted in 93,676 postmenopausal women ineligible or unwilling to participate in the clinical trials. To be eligible women had to be 50 to 79 years old, postmenopausal, and reside in the study recruitment area for at least 3 years after enrollment. Exclusion criteria were medical conditions predictive of a survival time of less than 3 years; conditions inconsistent with study participation such as alcoholism, drug dependency, mental illness, and dementia; and enrollment in another study. All participants provided written, informed consent according to the human subjects’ protection oversight at the 40 participating sites. Recruitment (1994–1998) was conducted through mailings to eligible women from large mailing lists. Women were followed through 2005 as part of the original study and were offered the opportunity to continue for an additional 5 years in the WHI extension study. After obtaining informed consent, yearly questionnaires were administered by mail between 2005 and 2010.

All OS participants underwent a baseline visit including physical measurements (height, weight, blood pressure, heart rate, waist and hip circumferences), blood specimen collection, a medication/supplement inventory, and completion of medical, family/reproductive history, lifestyle/behavioral factors, and quality-of-life questionnaires. Follow-up included an on-site clinic visit 3 years after enrollment and annual mailings (a medical history update and questionnaires about lifestyle and dietary habits, demographics, hormone therapy, and psychosocial variables). The WHI OS outcomes were coronary heart disease, stroke, breast and colorectal cancer, osteoporotic fractures, diabetes, and total mortality.

Study population

Inclusion criteria for this secondary analysis were completion of the follow-up year 5 (YR5) assessments, and absence of self-reported CVD and any cardiovascular events through YR5. Women who did not consent to the WHI extension study were censored at the date of last follow-up.

Exposure

Time spent in private spiritual activity was assessed only at YR5 using a self-administered questionnaire completed approximately 5 years (1999–2003) after enrollment in the original study asking how often the participant spent time in the following activities: Prayer, meditation, or reading religious literature during the prior year. The possible answers were never, a few times per year, a few times per month, about once a week, a few times per week, every day.

Outcome

The outcome for this analysis was fatal and nonfatal incident cardiovascular events, a cumulative endpoint defined as the first occurrence of nonfatal angina, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, coronary and carotid revascularization procedures, stroke, transient ischemic attack, peripheral arterial disease, and any adjudicated fatal cardiovascular event. Outcomes were identified by self-report on the medical history update or by reporting directly to clinic staff in the intervals between questionnaires. Centrally trained physicians adjudicated cardiovascular outcomes [32].

Covariates and other variables of interest

Covariates were selected based on the literature and/or whether they were associated with frequency of private spiritual activity, cardiovascular events, or both. Whenever possible, we used information collected at the same time (YR5) as frequency of private spiritual activity. When variables had not been collected at YR5 we used covariates collected at YR3 or at baseline, whichever was closest in time. Except for body mass index, all covariates were collected by means of self-administered questionnaires and included age, race/ethnicity (American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, Black or African-American, Hispanic/Latino, White, other), marital status (never married, married or in marriage-like relationship, widowed, divorced/separated), total years of education, and annual income (<$10,000; $10,000–19,999; $20,000–34,999; $35,000–49,999; $50,000–74,999; $75,000–99,999; $100,000–149,000; >$150,000; does not know). Risk factors for CVD included history of hypertension and diabetes, family history, smoking (ever, never, current), and body mass index (kg/m2 calculated from direct measurements of height and weight performed at YR3). Cholesterol levels were not measured in the entire OS cohort so history of elevated cholesterol requiring pharmacologic treatment was used as a proxy. Physical activity was calculated as energy expenditure from recreational physical activity (total metabolic equivalent task-hours per week). Alcohol intake was measured as the number of servings of alcohol per week. Psychosocial variables included social support (from the Medical Outcomes Study) [33]; physical functioning, emotional well-being, and satisfaction with quality of life (Medical Outcome Study 36-Item Health Survey) [34]; and depression (assessed using the shortened version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale) [35].

History of severe chronic diseases was defined as a self-reported history of severe noncardiovascular comorbidities before YR5, including diabetes, liver disease, dialysis, asthma, emphysema, lupus, Alzheimer disease, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, as well as all adjudicated cancer outcomes (except nonmelanoma skin cancers).

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe the baseline characteristics of the study population across categories of frequency of private spiritual activity. Analysis of variance F and independent χ2 tests were used to evaluate differences. The association between private spiritual activity (categorized as daily, once or more per week, less than once a week, and never) and cardiovascular events was evaluated using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models. We tested the assumption of the proportional hazard model by entering time dependent covariates into the model, and no violations were observed. Several models were fitted: Unadjusted, adjusted for age only (model 1), adjusted also for demographic variables (model 2), adjusted for all variables included in model 2 plus health behaviors (model 3), adjusted for model 3 variables plus cardiovascular risk factors (model 4), and adjusted for model 4 variables plus physical functioning, satisfaction with quality of life, and social support (model 5). The final model included model 5 variables plus depression and emotional well-being (model 6). The need for a separate model including psychological variables arose because such variables may be on the causal pathway linking spirituality and survival. In addition, we planned to conduct a subgroup analysis by presence/absence of history of severe chronic diseases before YR5.

Results are presented as unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals. P < .05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS/STAT version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

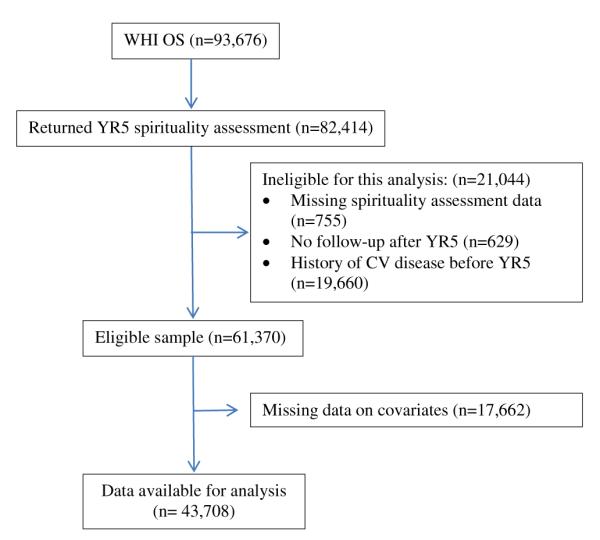

Figure 1 (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology [STROBE] diagram) [36] shows the flow of patients through this study. Of the original cohort of 93,676 women enrolled in the OS, 61,370 met the eligibility criteria for this study. Owing to missing information on covariates included in multivariate models, 17,662 women were excluded from the final analysis. These women tended to be more frequently African American (9% vs. 5.4%) or Hispanic (5% vs. 2.8%), less educated (postgraduate education, 28.3% vs. 34.6%) and more frequently current smokers (5% vs. 3.7%) compared with subjects included in the analysis, but had otherwise similar characteristics with regard to spiritual practices and cardiovascular events (no spiritual practice, excluded vs. included, 17.2% vs. 17.9; cardiovascular events, 6.3% vs. 5.8%).

Fig. 1.

STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology [STROBE] diagram. CV = cardiovascular; WHI-OS = Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study.

The baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Women with higher frequency of private spiritual activity tended to be older, less educated, of African American ancestry, widowed or never married, and of lower socioeconomic status; they also reported lower functional status scores. The prevalence of a diagnosis of a severe chronic disease before YR5 as well as of most risk factors for CVD was also higher in women reporting more frequent private spiritual activity. Specifically, these women were more frequently obese, used cholesterol-lowering drugs more often, had a history of hypertension or diabetes and reported lower levels of physical activity. The only exception among coronary risk factors was smoking, because women frequently engaging in private spiritual activity were less likely to be current or former smokers. Alcohol intake also was significantly lower among those with a higher frequency of private spiritual activity. Finally, women with more frequent spiritual practice had slightly better emotional well-being, higher social support, and a slightly lower prevalence of depression and anti-depressants use.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population, by frequency of private spiritual activity

| Private spiritual activity |

P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Never | Less than once per week |

Once or more per week |

Daily | ||

| n | 43,708 | 7829 (17.9) | 9109 (20.9) | 10,810 (24.7) | 15,960 (36.5) | |

| Age, yrs (mean [SD], year 5) | 67.96 (7.08) | 67.84 (7.30) | 67.53 (7.11) | 67.52 (6.95) | 68.58 (6.99) | <.0001* |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 139 (0.3) | 14 (0.2) | 27 (0.3) | 33 (0.3) | 65 (0.4) | <.0001† |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1376 (3.2) | 347 (4.4) | 364 (4.0) | 274 (2.5) | 391 (2.5) | |

| Black or African-American | 2380 (5.5) | 114 (1.5) | 300 (3.3) | 630 (5.8) | 1336 (8.4) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1217 (2.8) | 156 (2.0) | 206 (2.3) | 285 (2.6) | 570 (3.6) | |

| White not Hispanic | 38,179 (87.4) | 7120 (90.9) | 8127 (89.2) | 9515 (88.0) | 13,417 (84.1) | |

| Other | 417 (1.0) | 78 (1.0) | 85 (0.9) | 73 (0.7) | 181 (1.1) | |

| Years of education, (mean [SD]) | 15.1 (2.5) | 15.6 (2.5) | 15.3 (2.4) | 15.0 (2.4) | 14.8 (2.5) | <.0001† |

| Marital status (year 5) | ||||||

| Never married | 1978 (4.5) | 352 (4.5) | 380 (4.2) | 413 (3.8) | 833 (5.2) | <.0001† |

| Divorced or separated | 6069 (13.9) | 1262 (16.1) | 1420 (15.6) | 1414 (13.1) | 1973 (12.4) | |

| Widowed | 8292 (19.0) | 1255 (16.0) | 1528 (16.8) | 1975 (18.3) | 3534 (22.1) | |

| Presently married | 26,159 (59.9) | 4614 (58.9) | 5447 (59.8) | 6766 (62.6) | 9332 (58.5) | |

| Living in a marriage-like relationship | 1210 (2.8) | 346 (4.4) | 334 (3.7) | 242 (2.2) | 288 (1.8) | |

| Income, baseline (US$) | ||||||

| <10,000 | 990 (2.3) | 160 (2.0) | 147 (1.6) | 217 (2.0) | 466 (2.9) | <.0001† |

| 10,000–19,999 | 3675 (8.4) | 496 (6.3) | 598 (6.6) | 847 (7.8) | 1734 (10.9) | |

| 20,000–34,999 | 9265 (21.2) | 1288 (16.5) | 1743 (19.1) | 2337 (21.6) | 3897 (24.4) | |

| 35,000–49,999 | 8795 (20.1) | 1392 (17.8) | 1761 (19.3) | 2248 (20.8) | 3394 (21.3) | |

| 50,000–74,999 | 9530 (21.8) | 1741 (22.2) | 2045 (22.5) | 2462 (22.8) | 3282 (20.6) | |

| 75,000–99,999 | 4723 (10.8) | 1051 (13.4) | 1133 (12.4) | 1140 (10.6) | 1399 (8.8) | |

| 100,000–149,999 | 3625 (8.3) | 912 (11.7) | 936 (10.3) | 848 (7.8) | 929 (5.8) | |

| ≥150,000 | 2055 (4.7) | 41 (8.2) | 537 (5.9) | 470 (4.4) | 407 (2.6) | |

| Don’t know | 1050 (2.4) | 148 (1.9) | 209 (2.3) | 241 (2.2) | 452 (2.8) | |

| BMI, year 3 (kg/m2) | ||||||

| Normal (<25) | 18,258 (41.8) | 3858 (49.3) | 3951 (43.4) | 4107 (38.0) | 6342 (39.7) | <.0001† |

| Overweight (25 to <30) | 15,174 (34.7) | 2568 (32.8) | 3159 (34.7) | 3926 (36.3) | 5521 (34.6) | |

| Obese (≥30) | 10,276 (23.5) | 1403 (17.9) | 1999 (22.0) | 2777 (25.7) | 4097 (25.7) | |

| Depression, year 3 | 3653 (8.4) | 653 (8.3) | 757 (8.3) | 991 (9.2) | 1252 (7.8) | .0020† |

| Antidepressant use, year 3 | 3842 (8.8) | 692 (8.9) | 810 (8.9) | 1022 (9.5) | 1318 (8.3) | .0090† |

| Physical activity, year 5 (MET-hours/week; mean [SD]) | 14.25 (14.01) | 15.92 (14.99) | 14.88 (14.09) | 13.62 (13.43) | 13.50 (13.75) | <.0001‡ |

| High cholesterol requiring pills ever, baseline | 5095 (11.7) | 845 (10.8) | 1043 (11.5) | 1279 (11.8) | 1928 (12.1) | .0274† |

| History of hypertension, year 5 | 15,621 (35.7) | 2416 (30.9) | 3143 (34.5) | 3952 (36.6) | 6110 (38.3) | <.0001† |

| Diabetes, year 5 | 1996 (4.6) | 289 (3.7) | 368 (4.0) | 516 (4.8) | 823 (5.2) | <.0001† |

| Relative had heart attack, baseline | 21,882 (50.1) | 3736 (47.7) | 4515 (49.6) | 5527 (51.1) | 8104 (50.8) | <.0001† |

| Social support, baseline (mean [SD]) | 36.67 (7.37) | 36.26 (7.75) | 36.23 (7.40) | 36.59 (7.15) | 37.18 (7.26) | <.0001‡ |

| Physical functioning, year 3 (mean [SD]) | 82.13 (19.62) | 84.21 (18.76) | 83.14 (18.94) | 81.76 (19.42) | 80.78 (20.41) | <.0001‡ |

| Emotional well-being, year 3 (mean [SD]) | 81.37 (13.91) | 81.03 (14.50) | 80.72 (14.08) | 80.94 (13.82) | 82.20 (13.52) | <.0001‡ |

| Satisfaction with quality of life, year 3 (mean [SD]) | 8.31 (1.78) | 8.22 (1.84) | 8.21 (1.80) | 8.28 (1.77) | 8.44 (1.73) | <.0001‡ |

| Smoking status (year 5) | ||||||

| Never smoked | 22,748 (52.1) | 3430 (43.8) | 4396 (48.3) | 5722 (52.9) | 9200 (57.6) | <.0001† |

| Past smoker | 19,336 (44.2) | 4017 (51.3) | 4357 (47.8) | 4700 (43.5) | 6262 (39.2) | |

| Current smoker | 1624 (3.7) | 382 (4.9) | 356 (3.9) | 388 (3.6) | 498 (3.1) | |

| Alcohol servings per week, year 3 (mean [SD]) | 2.67 (5.23) | 3.84 (6.65) | 3.08 (5.50) | 2.48 (4.71) | 1.99 (4.45) | <.0001‡ |

| Diagnosis of severe chronic diseases before year 5 | 14,708 (33.7) | 2472 (16.8) | 2937 (20.0) | 3597 (24.5) | 5702 (38.8) | <.0001† |

BMI = body mass index; Depression = Center of Epidemiological Studies (CES-D) score > 0.06; MET = metabolic equivalent tasks.

Values are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

All variables collected at year 5 of follow-up unless otherwise specified.

Analysis of variance.

Chi-square.

Kruskal–Wallis.

The median duration of follow-up was 7 years, during which 2554 cardiovascular events were observed (402 fatal). Age-adjusted models (Table 2, Model 1) showed that women who reported weekly and daily spiritual practice had a higher risk of cardiovascular events compared with women who never engaged in such activity (HR, 1.16 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.02–1.31] for weekly vs. never; HR, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.11–1.40] for daily vs. never). In a series of models that further adjusted for other demographic factors (model 2), lifestyle habits (model 3), and cardiovascular risk factors (model 4), women who reported daily private spiritual activity had a significantly increased risk for cardiovascular events (HR in the fully adjusted model 1.16; 95% CI, 1.03–1.30) compared with women who did not reported such activity. Further adjustment for psychosocial measures (model 5) and depression and emotional well-being (model 6) did not modify these associations. We also fitted a model adjusting for presence/absence of severe chronic diseases in addition to the variables included in model 2 (age, ethnicity, marital status, income, and education), but the association between cardiovascular events and spiritual practice was not altered (HR, 1.08 [95% CI, 0.95–1.23] for weekly vs. never; HR, 1.13 [95% CI, 1.01–1.27] for daily vs. never). Finally, trend analysis showed that the risk of cardiovascular events increased with rising frequency of private spiritual activity (P for trend = .010).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events by frequency of private spiritual activity

| Private spiritual activity |

P for trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never (reference) | Less than once per week | Once or more per week | Daily | ||

| Cardiovascular events, n (%) | 408 (5.2) | 499 (5.5) | 612 (5.7) | 1035 (6.5) | |

| Unadjusted HR | 1.00 | 1.06 (0.93e1.21) | 1.12 (0.99e1.27) | 1.31 (1.17e1.47) | <.001 |

| Model 1 HR | 1.00 | 1.10 (0.96–1.25) | 1.16 (1.02–1.31) | 1.25 (1.11–1.40) | <.001 |

| Model 2 HR | 1.00 | 1.06 (0.93–1.21) | 1.08 (0.96–1.23) | 1.14 (1.01–1.28) | .025 |

| Model 3 HR | 1.00 | 1.07 (0.94–1.22) | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | 1.17 (1.04–1.31) | .008 |

| Model 4 HR | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.92–1.19) | 1.06 (0.94–1.21) | 1.14 (1.01–1.28) | .022 |

| Model 5 HR | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.92–1.19) | 1.07 (0.94–1.21) | 1.15 (1.03–1.30) | .011 |

| Model 6 HR | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.92–1.19) | 1.07 (0.94–1.21) | 1.16 (1.03–1.30) | .010 |

Cardiovascular events = cumulative endpoint (angina, coronary and carotid revascularization, stroke, transient ischemic attack, congestive heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, and any adjudicated cardiovascular death); CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression scale.

The analysis included women with complete data, cardiovascular mortality and cardiovascular events (n = 43,708).

Hazard ratios (HR) are reported with 95% confidence intervals.

Model 1, age-adjusted. Model 2, adjusted for age, ethnicity, marital status, income, and education. Model 3, model 2 plus physical activity (MET-hours), smoking status, alcohol servings/week. Model 4, model 3 plus body mass index, high cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes, and family history of myocardial infarction. Model 5, model 4 plus physical functioning, satisfaction with quality of life, social support. Model 6, model 5 plus CES-D and emotional well-being scores.

Subgroup analysis

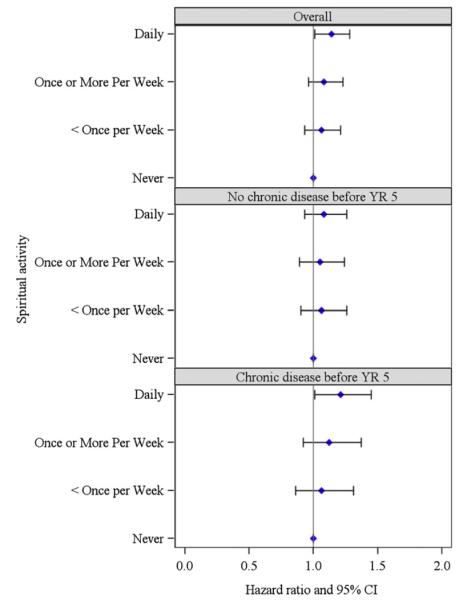

Table 3 and Figure 2 show the results of the subgroup analysis by presence/absence of self-reported severe chronic diseases before YR5. Results indicate that the presence of severe chronic diseases was not an effect modifier (P = .6449).

Table 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios of cardiovascular events by frequency of spiritual practice, results of the subgroup analysis by presence/absence of chronic disease before year 5

| n | CV events n (%) | Private spiritual activity |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never (reference) | <Once per week, HR (95% CI) | Once or more per week, HR (95% CI) | Daily, HR (95% CI) | |||

| No CDH | 29,000 | 1469 (5.1) | 1.00 | 1.06 (0.90–1.26) | 1.05 (0.89–1.24) | 1.08 (0.93–1.26) |

| CDH | 14,708 | 1085 (7.4) | 1.00 | 1.06 (0.86–1.31) | 1.12 (0.92–1.37) | 1.21 (1.01–1.45) |

CD = chronic disease history; CV = cardiovascular.

P < .0001 for differences in CV events by presence/absence of CDH.

P = .6449 for interaction term added to model 6.

The analysis included women with complete data (n = 43,708).

Hazard ratios (HR) are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Chronic disease history is defined as history of chronic disease reported before year 5 including cancer (except nonmelanoma skin cancer), diabetes, liver disease, kidney dialysis, asthma, emphysema, lupus, Alzheimer disease, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Data from The Women’s Health Initiative Study Group [31].

Fig. 2.

Adjusted associations between private spiritual activity and fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events, overall and by presence/absence of severe chronic diseases before year 5. Severe chronic diseases included any cancer (except nonmelanoma skin cancer), diabetes, liver disease, dialysis, asthma, emphysema, lupus, Alzheimer disease, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Discussion

In previous population-based studies, more frequent worship participation [3,10] or, among Jews, adherence to orthodox practices and teachings [11,12], were found to be associated with a reduced cardiovascular risk. In our study of a large population of community-dwelling postmenopausal women, however, when we focused our attention on frequency of meditation, prayer, or reading of religious texts, we found that this dimension of R/S was not associated with a reduced cardiovascular risk; in fact, women reporting daily private spiritual activity had a higher risk of cardiovascular events compared with women who reported no private spiritual activity.

The present study was designed to follow-up on the findings of a previous investigation conducted in the WHI-OS [8], which did not detect an association between baseline measures of R/S and cardiovascular risk; however, these measures did not include private spiritual activity. The relationship between multiple measures of R/S (worship attendance, prayer, and daily spiritual experience scores) and cardiovascular risk factors and events has been studied among more than 5000 participants aged 45 to 84 years in the MESA study [15]. As in the present study, higher levels of R/S, including prayer, were associated with greater risk of obesity and decreased risk of drinking and smoking. Unlike the results reported herein, among the MESA participants there was no significant association between frequency of prayer and cardiovascular risk. Our study, however, had a larger sample size and a longer duration of follow-up; in addition, even in the MESA analysis, the point estimate in the group with daily private spiritual activity, although not significant, indicated an increased risk of cardiovascular events in the more religiously involved.

A possible explanation for our findings would be confounding by the presence of severe chronic comorbidities; in fact, the prevalence of severe, chronic comorbidities before YR5 was associated with a higher frequency of private spiritual activity (Table 1). In multivariate models, however, the presence of severe chronic disease was not a confounder. Although the interaction term was not significant, the results of the stratified analysis nevertheless suggest that women with a prior diagnosis of severe, chronic diseases likely drive the association between private spiritual activity and increased cardiovascular risk. Similar findings have been reported in another study conducted in an elderly population [28] in which the protective association between private spiritual activity and reduced overall mortality was detected only in individuals without impairment in activities of daily living, and was not detected in the cohort reporting such a condition.

Our results are not consistent with some of the previously published studies indicating that R/S is associated with a lower cardiovascular risk [9]. It seems, however, that our knowledge about the link between R/S and cardiovascular health is far from being conclusive for several reasons. For example, studies that have detected a protective association between R/S and cardiovascular risk measured very different aspects of the R/S experience. Some researchers measured worship attendance only [3,10], whereas others measured self-reported religiosity within specific religious groups [1,11,12]. Studies also differed as to whether they adjusted for coronary risk factors (i.e., diabetes, high cholesterol) and other variables that may confound the association between R/S and cardiovascular mortality. The only studies extensively adjusting for coronary risk factors and reporting an association between R/S (defined as being orthodox vs. secular) and reduced risk of cardiovascular mortality or acute myocardial infarction were conducted in a Jewish population in Israel [1,11,12]. Orthodox Judaism, however, is somewhat unique in that it regulates every aspect of life [37,38], thus raising the question of whether these results are generalizable to other religious affiliations. The populations studied in other investigations were also heterogeneous with regard to their age and health status, with protective associations between R/S and cardiovascular risk usually shown in younger and healthier populations [3,10,12,13], but not in older persons with concomitant diseases [8,9,16,17]. The direction and the magnitude of the association between R/S and cardiovascular risk may change depending on whether the exposure began in healthy individuals and early in life as opposed to a later stage, when individuals may turn to religion as a coping mechanism in the face of declining health and advancing age [28,39]. Finally, the duration of follow-up differed greatly among studies; studies reporting a protective effect usually had a longer follow-up duration [3,10,11].

This study has several strengths: First, a relatively long duration of follow-up; second, extensive adjustment for coronary risk factors, and demographic and psychosocial variables; third, a relatively understudied population (women); and fourth, the validation of cardiovascular outcomes. The limitations of this analysis include the assessment of private spiritual activity as an aggregate only, with the resulting inability to assess associations between specific activities (i.e., meditation and/or prayer vs. reading of religious texts) and cardiovascular events; and the collection of private spiritual activity data only at YR5. Furthermore, some covariates were not collected at the same time point (YR5) as the spirituality activity assessment, and we had to use baseline or YR3 covariates. Residual confounding (in particular regarding coronary risk factors such as blood pressure and serum lipid levels that were not directly measured) as well as selection bias (owing to the large number of women excluded) are additional limitations of this analysis. Also, we cannot rule out the possible contribution of survivor bias (e.g., women with lower levels of private spirituality activity not surviving long enough to be included in the current analysis) to our findings. Finally, results are not generalizable to younger or male populations, and to women that were excluded from participation in the parent study (i.e., women with alcoholism, drug dependency, mental illness, and dementia).

In conclusion, our results confirm recent indications that higher R/S does not prevent fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events [8,15], at least in older female populations. Further research involving younger and healthier populations is needed to achieve a better understanding of the role of R/S in the prevention of cardiovascular risk.

Acknowledgments

Short list of WHI Investigators.

Program Office: (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland) Elizabeth Nabel, Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller.

Clinical Coordinating Center: (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA); Ross Prentice, Garnet Anderson, Andrea LaCroix, Charles L. Kooperberg, Ruth E. Patterson, Anne McTiernan; (Medical Research Labs, Highland Heights, KY) Evan Stein; (University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA) Steven Cummings.

Clinical Centers: (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY) Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller; (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) Aleksandar Rajkovic; (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) JoAnn E. Manson; (Brown University, Providence, RI) Charles B. Eaton; (Emory University, Atlanta, GA) Lawrence Phillips; (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) Shirley Beresford; (George Washington University Medical Center, Washington, DC) Lisa Martin; (Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor- UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA) Rowan Chlebowski; (Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland, OR) Yvonne Michael; (Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA) Bette Caan; (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI) Jane Morley Kotchen; (MedStar Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC) Barbara V. Howard; (Northwestern University, Chicago/Evanston, IL) Linda Van Horn; (Rush Medical Center, Chicago, IL) Henry Black; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA) Marcia L. Stefanick; (State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY) Dorothy Lane; (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) Rebecca Jackson; (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL) Cora E. Lewis; (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ) Cynthia A Thomson; (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY) Jean Wactawski-Wende; (University of California at Davis, Sacramento, CA) John Robbins; (University of California at Irvine, CA) F. Allan Hubbell; (University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA) Lauren Nathan; (University of California at San Diego, LaJolla/Chula Vista, CA) Robert D. Langer; (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH) Margery Gass; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL) Marian Limacher; (University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI) J. David Curb; (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA) Robert Wallace; (University of Massachusetts/Fallon Clinic, Worcester, MA) Judith Ockene; (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ) Norman Lasser; (University of Miami, Miami, FL) Mary Jo O’Sullivan; (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) Karen Margolis; (University of Nevada, Reno, NV) Robert Brunner; (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) Gerardo Heiss; (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) Lewis Kuller; (University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN) Karen C. Johnson; (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX) Robert Brzyski; (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI) Gloria E. Sarto; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Mara Vitolins; (Wayne State University School of Medicine/Hutzel Hospital, Detroit, MI) Michael Simon.

Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker.

Funding/support: The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts N01WH22110, 24152, 32100-2, 32105-6, 32108-9, 32111-13, 32115, 32118-32119, 32122, 42107-26, 42129-32, and 4422.

References

- [1].Kark JD, Shemi G, Friedlander Y, Martin O, Manor O, Blondheim SH. Does religious observance promote health? Mortality in secular vs. religious kibbutzim in Israel. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(3):341–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.3.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(6):957–61. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hummer R, Rogers R, Nam C, Ellison C. Religious involvement and U.S. adult mortality. Demography. 1999;36(2):273–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gillum RF, King DE, Obisesan TO, Koenig HG. Frequency of attendance at religious services and mortality in a U.S. National Cohort. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(2):124–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Enstrom JE, Breslow L. Lifestyle and reduced mortality among active California Mormons, 1980-2004. Prev Med. 2008;46(2):133–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Koenig HG, Hays JC, Larson DB, George LK, Cohen HJ, McCullough ME, et al. Does religious attendance prolong survival? A six-year follow-up study of 3,968 older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(7):370–6. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.7.m370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].House JS, Robbins C, Metzner HL. The association of social relationships and activities with mortality: prospective evidence from the Tecumseh Community Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;116(1):123–40. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schnall E, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Swencionis C, Zemon V, Tinker L, O’Sullivan MJ, et al. The relationship between religion and cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Psychol Health. 2010;25(2):249–63. doi: 10.1080/08870440802311322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chida Y, Steptoe A, Powell LH. Religiosity/spirituality and mortality. A systematic quantitative review. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(2):81–90. doi: 10.1159/000190791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Oman D, Kurata JH, Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD. Religious attendance and cause of death over 31 years. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2002;32(1):69–89. doi: 10.2190/RJY7-CRR1-HCW5-XVEG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Goldbourt U, Yaari S, Medalie J. Factors predictive of long-term coronary heart disease mortality among 10,059 male Israeli civil servants and municipal employees. A 23-year mortality follow-up in the Israeli Ischemic Heart Disease Study. Cardiology. 1993;82(2):100–21. doi: 10.1159/000175862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Friedlander Y, Kark J, Stein Y. Religious orthodoxy and myocardial infarction in Jerusalem–a case control study. Int J Cardiol. 1986;10(1):33–41. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(86)90163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gupta R, Prakash H, Gupta VP, Gupta KD. Prevalence and determinants of coronary heart disease in a rural population of India. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(2):203–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00281-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Burazeri G, Goda A, Kark JD. Religious observance and acute coronary syndrome in predominantly Muslim Albania: a population-based case-control study in Tirana. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(12):937–45. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Feinstein M, Liu K, Ning H, Fitchett G, Lloyd-Jones DM. Burden of cardiovascular risk factors, subclinical atherosclerosis, and incident cardiovascular events across dimensions of religiosity: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2010;121(5):659–66. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.879973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Colantonio A, Kasl SV, Ostfeld AM. Depressive symptoms and other psychosocial factors as predictors of stroke in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136(7):884–94. doi: 10.1093/aje/136.7.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Ironson G, Thoresen C, Powell L, Czajkowski S, et al. Spirituality, religion, and clinical outcomes in patients recovering from an acute myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(6):501–8. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180cab76c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wallace RK, Benson H, Wilson AF. A wakeful hypometabolic physiologic state. AJP - Legacy. 1971;221(3):795–9. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1971.221.3.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Berntson GG, Norman GJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Spirituality and autonomic cardiac control. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(20):198–208. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9027-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bernardi L, Sleight P, Bandinelli G, Cencetti S, Fattorini L, Wdowczyc-Szulc J, et al. Effect of rosary prayer and yoga mantras on autonomic cardiovascular rhythms: comparative study. BMJ. 2001;323(7327):1446–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7327.1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Billman GE. A comprehensive review and analysis of 25 years of data from an in vivo canine model of sudden cardiac death: implications for future anti-arrhythmic drug development. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111(3):808–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Airaksinen KE, Ylitalo A, Niemela MJ, Tahvanainen KU, Huikuri HV. Heart rate variability and occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias during balloon occlusion of a major coronary artery. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83(7):1000–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].La Rovere MT, Bigger JT, Jr, Marcus FI, Mortara A, Schwartz PJ. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart-rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. ATRAMI (Autonomic Tone and Reflexes After Myocardial Infarction) Investigators. Lancet. 1998;351(9101):478–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zamarra JW, Schneider RH, Besseghini I, Robinson DK, Salerno JW. Usefulness of the transcendental meditation program in the treatment of patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(10):867–70. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)89184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Benson H, Alexander S, Feldman C. Decreased premature ventricular contractions through use of the relaxation response in patients with stable ischaemic heart-disease. Lancet. 1975;2(7931):380–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92895-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Advanced data from Vital and Health Statistics. no. 343. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville (MD): 2002. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yates JS, Mustian KM, Morrow GR, Gillies LJ, Padmanaban D, Atkins JN, et al. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer patients during treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(10):806–11. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0770-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Helm HM, Hays JC, Flint EP, Koenig HG, Blazer DG. Does private religious activity prolong survival? A Six-Year Follow-up Study of 3,851 Older Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(7):M400–5. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.7.m400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sloan RP, Bagiella E. Claims about religious involvement and health outcomes. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(1):14–21. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Koenig H. Commentary: Why do research on spirituality and health, and what do the results mean? J Relig Health. 2012;51(2):460–7. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9568-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].The Women’s Health Initiative Study Group Design of the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. Control Clin Trial. 1998;19(1):61–109. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Curb JD, McTiernan A, Heckbert SR, Kooperberg C, Stanford J, Nevitt M, et al. Outcomes ascertainment and adjudication methods in the Women’s Health Initiative. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9):S122–8. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, Prusoff BA, Locke BZ. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;106(3):203–14. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Helmreich W. The world of the Yeshiva: an intimate portrait of Orthodox Jewry. The Free Press; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schnall E. Multicultural counseling and the orthodox Jew. J Couns Dev. 2006;84(3):276–82. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Krause N, Van Tran T. Stress and religious involvement among older blacks. J Gerontol. 1989;44(1):S4–13. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.1.s4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]