Abstract

Malignant gliomas contain stroma and a variety of immune cells including abundant activated microglia/macrophages. Mounting evidence indicates that the glioma microenvironment converts the glioma-associated microglia/macrophages (GAMs) into glioma-supportive, immunosuppressive cells; however, GAMs can retain intrinsic anti-tumor properties. Here, we review and discuss this duality and the potential therapeutic strategies that may inhibit their glioma-supportive and propagating functions.

1. Introduction

Microglia can constitute up to 10% of cells in the central nervous system (CNS) and are distinctive from other CNS cells such as astrocytes and oligodendrocytes [1]. Distinguishing features of microglia are their “ramified” branches that emerge from the cell body that communicate with surrounding neurons and other glial cells. Microglia rapidly respond to infectious and traumatic stimuli by adopting an “amoeboid” activated phenotype and can produce a variety of pro-inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, chemokines, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and nitric oxide (NO), which contribute to the clearance of pathogenic infections. However, prolonged or excessive activation may result in pathological forms of inflammation that contribute to the progression of neurodegenerative and neoplastic diseases [2].

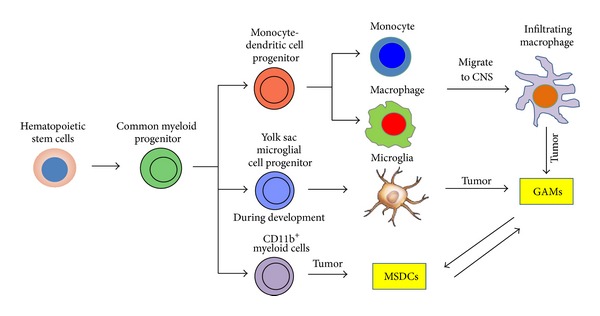

Gene transcript clustering analysis reveals that microglia have close lineage relationship with bone-marrow-derived macrophages, indicating that these cells arise from the bone marrow and circulating monocytes/macrophages [3]. However, recent findings suggest that microglia originate from yolk sac macrophages that migrate into the CNS during early embryogenesis [4] (Figure 1). Further confounding the issue regarding the origin of CNS microglia are studies demonstrating the generation of microglia-like cells from a murine embryonal carcinoma cell line (P19) during neural differentiation [5]. Regardless of the origin, the microglia/macrophage population are usually the dominant glioma-infiltrating immune cells (5–30%) [6].

Figure 1.

Cell lineage derivation of the CNS microglia/macrophage is depicted, with arrows indicating lineage relatedness. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a lineage term describing glioma-associated microglia/macrophages (GAMs).

Studies during the 90s demonstrated a positive correlation between the number of microglia/macrophage and glioma malignancy [7, 8]. Furthermore, microscopic analysis of microglia morphology in high-grade glioma revealed an activated state, described by amoeboid or spherical shape [9, 10]. Morioka et al. have found that reactive microglia form a dense band that surround the tumor mass and can extend along the corpus callosum into the contralateral cerebral hemisphere [11]. These data would indicate that microglia react to brain tumors; however, it remains to be determined whether this response represents an active anti-tumor defense mechanism or a tumor-supportive one. Likewise, microglia are commonly found “trapped” in gliomas and it is unclear if they have coproliferated with the tumor cells. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)/scatter factor (SF), which plays a role in glioma motility and mitogenesis, may be one chemokine responsible for the microglia infiltration in malignant gliomas [12]. Additionally or alternatively, monocyte chemotactic protein-3 (MCP-3) was found to correlate with GAM infiltration [13] and to act as a chemokine. Furthermore, it has been reported that tumor necrosis factor (TNF) dependent action enhances macrophage/microglia recruitment in glioma [14]. Other chemoattractants that have been shown to stimulate microglia/macrophage migration into the tumor include colony stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) [15, 16], macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) [17], and glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) [18]. However, recent studies have emphasized a predominant role of granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-SCF) in microglia/macrophage attraction [19] which confirmed previous reports [20, 21]. Nonetheless, the increased number of microglia/macrophages found in high-grade gliomas has suggested that they may have a pro-neoplastic role [8].

No consensus definitive marker that distinguishs between microglia and macrophages has thus far been defined. As such, many investigators use the more general term “microglia/macrophages” instead of microglia alone. CD163, CD200, CD204, CD68, F4/80, and the lectin binding protein Iba-1 can be used as general markers of microglia/macrophages [22, 23]. P2X4R expression can define a distinct subset of GAMs [24]. Furthermore, allograft inflammatory factor-1 (AIF-1) and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) can also be used to define a distinct subset of GAMs in rat and human gliomas [25, 26]. However, the most commonly used criterion to distinguish CNS microglia from macrophages is the differential CD45 expression (CD45low for microglia and CD45high for macrophages) on CD11b+ CD11c+ cells [27–29]. The robustness of this is questionable.

Another confounding issue in defining and clarifying the biological role of GAMs is their distinction from myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). The MDSCs are induced in response to various tumor-derived cytokines and have been shown to inhibit tumor-specific immune responses [30]. However, this is not an absolute since MDSCs isolated from mouse brain tumors, although expressing markers consistent with an immune suppressive phenotype (CCL17, CD206, and CD36), still express proinflammatory IL-1β, TNF-α, and CXCL10 [31]. Currently, there are two presumed MDSC populations: monocytic and granulocytic. Thus far little is known about the biology and phenotypic characteristics of MDSCs within gliomas but presumptively GAMs would be closer in the continuum to the monocytic MDSC subset based on CD11b+ expression and function. Specifically, MSDCs only weakly present glioma antigens to cytotoxic T cells and express FasL, which contributes to the local immunosuppressive milieu of malignant gliomas [32], similar immunological functions attributed to GAMs [33]. Furthermore, the MDSCs have been shown to inhibit T cell activity by NO production [34]; however, this immune suppression was postulated to be distinct from CNS microglia.

2. The M1/M2 Continuum

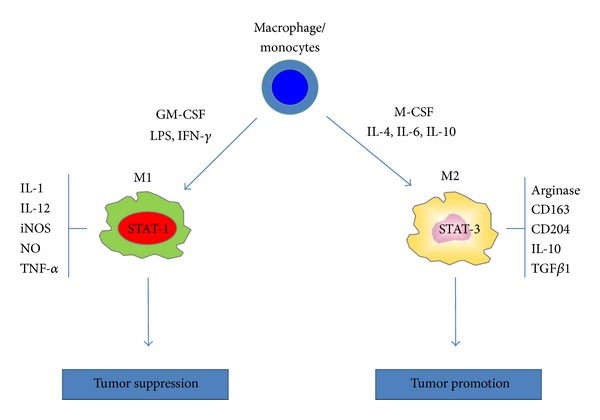

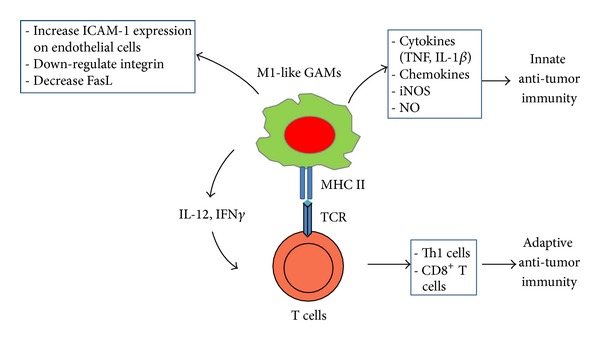

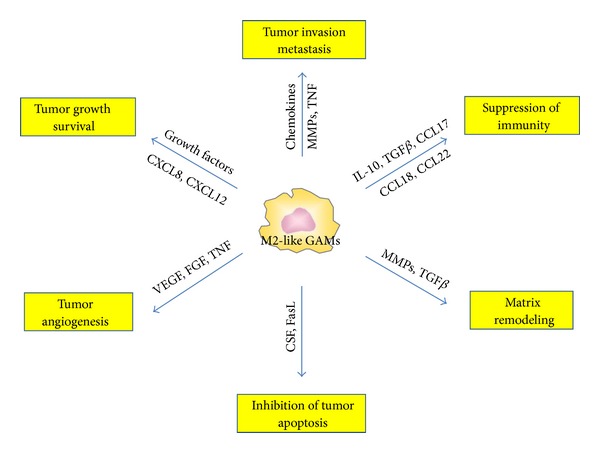

The M1/M2 continuum has been applied to CNS infiltrating macrophage/monocytes in the context of inflammation or tumor. Classically activated macrophages assume a M1 phenotype characterized by the expression of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT-1) and the production of iNOS (Figure 2). The M1 cell is capable of stimulating anti-tumor immune responses by presenting antigen to adaptive immune cells, producing pro-inflammatory cytokines and phagocytosing tumor cells [35] (Figure 3). Whereas the alternatively activated pathway, M2, is characterized by the expression of surface CD163 and CD204, expression of intracellular STAT-3 and the production of arginase [36, 37] (Figure 2). M2 polarization prevents the production of cytokines required to support tumor-specific CD8+ T cells, and CD4+ T helper 1 (Th1) and promotes the function of CD4+ regulatory T cells, and are therefore tumor supportive [38, 39] (Figure 4). Multiple lines of evidence suggest that the GAMs are likely skewed to the alternatively activated M2 macrophage phenotype. However, to date, it should be noted that a comprehensive characterization of the M1 and M2 composition of gliomas has not been conducted.

Figure 2.

CNS macrophage/monocytes differentiate into polarized macrophage subsets when exposed to different cytokine milieu. In the presence of granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interferon-(IFN) γ, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and other microbial products, monocytes differentiate into M1 macrophages. In the presence of macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF), interleukin-(IL) 4, IL-6, IL-10 and immune suppressive molecules (corticosteroids, vitamin D3, prostaglandins), monocytes differentiate into M2 macrophages. M1 and M2 subsets differ in terms of phenotype and functions. M1 cells have high anti-microbial activity, immune stimulatory functions and tumor cytotoxicity and express the signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT-1). M2 cells have high scavenging ability, promote tissue repair and angiogenesis, favor tumor progression and express STAT-3.

Figure 3.

Glioma-associated microglia/macrophages (GAMs) have anti-tumoral potential. In certain circumstances, GAMs can be activated and polarized to a M1-like phenotype that can contribute to both innate and adaptive anti-tumor immunity.

Figure 4.

Glioma-associated microglia/macrophages (GAMs) are tumor supportive. Chemokines have a prominent role as they induce neoangiogenesis, activate matrix-metalloproteases (MMPs) and stroma remodeling, and direct tumor growth. Selected chemokines and immunosuppressive cytokines inhibit the anti-tumor immune response.

Glioma cells secrete a wide variety of factors that suppress immune cells, such as IL-10, IL-4, IL-6, M-CSF, macrophage inhibitory factor (MIF), TGFβ, and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) [17, 40–43]. These cytokines are known to promote a M2 phenotype and/or to suppress the M1 phenotype. For example, TGFβ inhibits microglia cell proliferation and the production of proinflammatory cytokines in vitro [44]. IL-4, IL-6 and IL-10 have been shown to polarize microglia to an M2-like phenotype [45]. Other immunosuppressive mechanisms such as the downregulation ICAM-1 and expression of immune inhibitory molecules such as B7-H1 can also dismantle the microglia-T cell combined immune recognition and clearance of gliomas [46]. Furthermore, gliomas induce upregulation and expression of HLA-G and HLA-E by GAMs in a majority of glioblastomas, thus hindering anti-glioma activity [47]. The anti-glioma functional impairment of GAMs likely occurs relatively late in the course of glioblastoma tumor growth, potentially providing a window of opportunity for therapeutic strategies directed towards preventing their functional impairment [48]. Of note, the M1/M2 distinction is a continuum and simplification of the complex T cell and GAM interactions and the subsequent outcome.

Similar impairments of microglia/macrophage anti-tumor activity have been reported for brain metastasis. In the region where the tumor mass is situated, only a few microglia express inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). On one hand, the microglia accumulate as a result of migration and proliferation, have an ameboid appearance, and appear to actively respond to the metastatic lung cancer cells in the brain by tightly encapsulating the tumor mass. On the other hand, the lack of positivity of either iNOS or TNF-α in double-labeling experiments indicates that the microglia immunological functions including cytotoxicity, phagocytosis, and antigen presentation are impaired [49]. Microglia have also been shown to promote invasion and colonization of the brain by breast cancer by serving both as active transporters and guiding rails. This is antagonized by inactivation of microglia as well as by Wnt signaling inhibition. Therefore, microglia were shown to be critical for the successful colonization of the brain by epithelial cancer cells, suggesting that inhibition of microglia could also be a promising anti-metastatic strategy [50].

Despite the immunosuppressive environment of human gliomas, GAMs are capable of some innate immune responses such as phagocytosis, cytotoxicity and TLR expression but are not competent in secreting key pro-inflammatory cytokines [51]. GAMs responsiveness to activators is impaired when compared to microglia/macrophages isolated from normal brain; specifically, the former has an impaired capacity to be stimulated by TLR agonist to secrete cytokines, upregulate costimulatory molecules, and activate anti-tumor effector T cells [33]. Understanding the mechanism of these differences may be critical in the development of novel immunotherapies for malignant gliomas [52].

The GAMs do not always display MZ functions. Insoluble matrix components derived from malignant glioma cells have been shown to enhance microglia activation [30]. These activated microglia can then induce glioma cell death by blockade of basal autophagic flux inducing secondary apoptosis/necrosis [53]. Signaling through the JAK-2-STAT-5 pathway was shown to be essential for IL-3-induced activation of microglia [54]. Furthermore, microglia/macrophages depletion increased glioma tumor volume by 33%. This was not believed to be secondary to the loss of microglia tumoricidal activity because phagocytosis or apoptosis of glioma cells was rarely observed. The loss of anti-tumor effect was also not due to alterations in tumor vasculature. Rather, the investigators found that depletion of a subset of CD86+ microglia with M1-like characteristics could present alloantigen and secrete stimulatory cytokines that promoted the expansion of the CD8+ T cells and was likely the etiology for enhanced glioma growth [55].

Alternatively, M2-like GAMs also promote glioma growth/survival via enhancing angiogenesis and inhibiting tumor apoptosis. GAMs have been shown to release growth factors such as VEGF, PDGF, and members of the FGF family, and a correlation has been shown between GAM numbers and tumor vascularity in gliomas [56]. Furthermore, these growth factors sustain malignant cell survival and subsequent tumor growth. Lastly, GAMs are a major source of FasL expression, which likely contributes to the suppression of malignant glioma apoptosis [32].

Glioma regression has also been correlated with greater numbers of T cells and microglia, suggesting that the combined mobilization of peripheral and CNS endogenous immune cells is required for eradicating large intracranial tumors [57]. Some soluble factors from reactive microglia are capable of enhancing the expression of ICAM-1 on the brain endothelial cells (ECs). As a consequence, large numbers of tumor-primed T lymphocytes can adhere to EC and migrate across the EC monolayer [58]. Finally, antibody-dependent cell mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) has also been shown to be involved in microglia anti-tumor activities. Microglia derived from brain cortices of newborn mice were shown to lyse human tumor cell lines expressing different levels of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in the presence of a monoclonal antibody specific to EGFR [59]. Reconciliation of the cumulative data would indicate that GAMs can be either M1 or M2 or some were in between, but the functional outcome will depend on the relative composition of M1 and M2 cells within the glioma.

3. Interplay between GAMs and Gliomas

It is becoming apparent that crosstalk exists between the GAMs and the brain tumor cells. Gliomas promote the recruitment, proliferation, and M2 polarization of microglia/macrophages; reciprocally, GAMs facilitate the survival, growth, and especially the spread of glioma cells (Figure 4). When activated in the presence of glioma, microglia invade the tumor. The microglia then secrete a variety of factors that degrade the CNS matrix. The glioma cells simultaneously invade and expand into the dissociated tissue by utilizing the same corridor paved by laminin on astrocytic projection for microglia invasion into the tumors [60–62]. Glioma secreted factors, by engaging the toll-like receptors and the p38 MAPK pathway, trigger the expression and activity of membrane type 1 metalloprotease (MT1-MMP) on GAMs. The GAM MT1-MMP expression then in turn activates glioma-derived pro-MMP-2 that subsequently promotes glioma invasion. A deficiency of MyD88, an upstream mediator of MT1-MMP, or microglia depletion, largely attenuates glioma expansion in vivo [62]. Furthermore, in brain slices inoculated with glioma cells, increased activity of metalloprotease-2 was directly correlated with the abundance of microglia [63]. Another GAM-associated mechanism, the CX3CR1/CX3CL1 interaction, can also induce MMPs production resulting in glioma invasion [64]. A recently described factor, STI1 (cochaperone stress inducible factor 1) secreted by microglia was shown to favor tumor growth and invasion through the participation of MMP-9 [65]. Thus, glioma cells stimulate microglia to increase the breakdown of extracellular matrix, thereby, promoting glioma invasion.

Substantially more controversial is whether microglia initiate or participate during early gliomagenesis. Neurodegeneration, neurotoxicity, and neuroinflammation are associated with chronic microglia activation that has been postulated to contribute to gliomagenesis [66–68]. Cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) in microglia/macrophages might represent a key regulatory mechanism in the inflammatory processes associated with neoplasia [69]. COX-1 and COX-2 differential accumulation is observed in microglia/macrophages and astrocytes during oligodendroglioma progression in vivo [70]. Furthermore, induction of COX-2 in microglia contributes to the deleterious effects of prostanoids in cerebral edema formation during the progression of oligodendrogliomas [71]. Increased c-Jun-NH2-kinase signaling in neurofibromatosis-1 heterozygous (Nf1+/−) microglia was shown to promote optic glioma proliferation [72] and glioma growth [73]. Interestingly, IL-4 or IFN-γ-mediated microglia activation differentially induces oligodendrogenesis and neurogenesis, respectively, from adult stem/progenitor cells. It thus appears that how microglia are activated determines their ability to either support or impair cell renewal and differentiation from adult stem cells [74].

Glioblastomas are believed to arise from glioma stem cells (GSCs). GSCs are phenotypically similar to normal stem cells, can express CD133, and possess self-renewal potential [75]. GSCs recapitulate the original polyclonal tumors when xenografted into nude mice and mediate chemo- and radiation resistance, thereby, leading to tumor progression and recurrence. A positive correlation is found between the degree of infiltration of GAMs and the density of GSCs. The capacity of GSCs to recruit GAMs was found to be stronger than glioma cell lines indicating that the GSCs play a predominant role in microglia/macrophages tropism to glioma [76]. In addition, recent mechanistic studies by another group showed that TGFβ1 released by GAMs promoted the expression of MMP-9 by GSCs, and TGFR2 knockdown reduced the invasiveness of these cells in vivo [77].

We have previously shown that GSCs produce a variety of cytokines known to recruit and polarize the microglia/macrophages to become immunosuppressive. The GSC-conditioned medium polarized the microglia/macrophage to an M2 phenotype, inhibited microglia/macrophage phagocytosis, induced the secretion of the immunosuppressive cytokines IL-10 and TGFβ1 and enhanced the capacity of these cells to inhibit T-cell proliferation [44]. The inhibition of antigen-presenting capabilities of GAMs by glioma tumor cells has also been demonstrated [25]. Previously, glioma-derived M-CSF was shown to induces markers reflective of the M2 phenotype CD163 and CD204 on monocytes, and in turn these differentiated microglia/macrophage facilitated tumor growth. Both the extent of M-CSF production and CD163+ and CD204+ expression on microglia were correlated with glioma grade [17]. A direct correlation has been shown between the immunogenicity of glioma tumor cells and the GAM content and their antigen-presenting function [78, 79]. In addition, the metabolic status of the microglia is altered by the glioma environment [80]. Abundant amounts of ATP released by the glioma have been suggested to trigger P2X7R signaling, resulting in increase of MIP-1α (macrophage inflammatory protein-1α) and MCP-1 (monocyte chemoattractant protein-1) in GAMs [81]. Cumulatively these data indicate that there is a strong interaction that occurs between the GAM and glioma that ultimately influences the biological behavior of each one.

4. Therapeutic Manipulation of the GAM

A variety of therapeutic anti-glioma strategies have suggested that modulation of the GAM population may contribute to therapeutic efficacy. Inhibition of experimental rat glioma growth by decorin (TGFβ antagonism) gene transfer was associated with decreased microglia infiltration suggesting that the GAMs were participate in the regression of decorin-expressing rat C6 gliomas [82]. Recent studies have demonstrated that ablation of CD11b+ cells in ganciclovir-treated CD11b-HSVTK mice [83] or in vivo targeting folate receptor β (FRβ)-expressing tumor-associated macrophages, decreases tumor size and improves animal survival [84]. The presence of significant anti-tumor immunity following herpes simplex virus 1 thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) and ganciclovir (GCV) treatments suggests that the immune system plays a critical role in the sustained tumor regressions associated with these treatments. Histologic examination of the brains of the successfully treated animals demonstrated residual tumor cells and inflammatory cells consisting predominantly of macrophages/microglia and T cells [85]. Another report demonstrates that a reduction of peripheral CD163+ macrophages in vivo and the depletion of CD68+ macrophage/microglia within brain slice ex vivo increase the intratumoral oncolytic viral titer to 5-fold and 10-fold, respectively, [86].

Therapeutic targeting of the GAM could be directed toward their activation (Table 1). Clearly, the goal of therapeutically targeting GAMs would be to selectively inhibit M2 while enhancing M1 functions (Table 2). The latter approach would include strategies that (1) inhibit the molecular mechanisms used by M2 cells to block lymphocyte reactivity and proliferation; (2) induce M2 apoptosis and/or trafficking to the tumor; or (3) force GAMs to the M1 phenotype. Inhibition of the M2-like activation of tumor-infiltrating macrophages was shown to significantly reduce glioma growth [37]. As such, STAT-3 is an attractive candidate since this pathway mediates glioblastoma-mediated M2 skewing and immune suppression. STAT-3 blockage by WP1066 stimulates the immune activation of GAMs, as evidenced by their increased expression of costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 [117]. Furthermore, in vivo STAT-3 inhibition in murine GAMs was shown to reduce expression of immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 and IL-6, while stimulating production of pro-inflammatory TNF-α [118]. Another therapeutic option is glycoprotein T11TS, which has been found to upregulate MHC class II, CD2 and CD4 expression in microglia in vivo in a rat glioma model [40]. Because macrophages/microglia express the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AchR) on their surface, a short AchR-binding peptide derived from the rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) could also be used for targeted delivery of siRNA to macrophages for anti-tumor treatment. This peptide was fused to nona-D-arginine residues (RVG-9dR) to enable siRNA binding [124]. Recently, GAMs were shown to enhance GSCs' invasion via the TGFβ1 signaling pathway [77]. shRNA against TGFβ1 receptor (TGFβR) on tumor-associated macrophages strongly inhibited glioma invasiveness, indicating that TGFβR is a potential therapeutic target [112]. Several small molecules exist with TGFβR inhibitor activity that could be utilized as GAM modulatory agents. Studies of Carpentier et al. [87] revealed that intratumoral injections of oligodeoxynucleotides containing CpG motifs (CpG-ODN) trigger both innate and specific immunities, driving the immune response towards the Th1 phenotype. On the other hand, glioma-bearing animals treated with minocycline showed increased survival [125] and reduced glioma invasion by attenuated microglia MT1-MMP expression [106].

Table 1.

Microglia activating agents.

| Molecule/agent | Classification | Mechanism/action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CpG-ODN | TLR9 ligand | Increases microglia tumor infiltration and enhances the antigen-presenting capacity | [87–89] |

| poly (I:C) | TLR3 ligand | Unknown soluble factors | [90] |

| IL-12 | Th1 cytokine | Increases tumor infiltration and enhances TRAIL and phagocytosis | [91, 92] |

| TNF | Th1 cytokine | Enhances glioma cytotoxicity | [93] |

| IFN-γ | Th1 cytokine | Upregulates class II MHC antigen expression | [94] |

| Cytotoxic T cells | Immune cells | Induce microglia activation and recruitment | [95, 96] |

| C1q, complement receptor 3 (CR3) | Complement | Mediates elimination of tagged synapses and activates microglia | [97, 98] |

| T11TS/SLFA-3 | Glycopeptide | Induces MHC class II expression and facilitates SLFA3/T11TS-CD2 immune activation | [99, 100] |

| Ceramide | Sphingolipid | Enhances microglia production/secretion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) | [101] |

| Ganglioside | Glycosphingolipid | Activates microglia via protein kinase C and NADPH oxidase, which regulate activation of NF-κB | [102] |

| Adenosine | Nucleoside | Acts via A1 adenosine receptors in microglia | [60] |

| Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2 (TREM2) | Innate immune receptor | Increases phagocytosis | [103] |

| Prothrombin | Blood-clotting protein | Activates microglia via kringle-2 domain | [104] |

| Propentofylline (PPF) | Methylxanthine | Inhibits microglia migration toward tumor cells and decreases MMP-9 expression | [105] |

| Minocycline | Antibiotic | Reduces glioma expansion and invasion by attenuating microglia MT1-MMP expression | [106] |

| Cyclosporin (CsA) | Immunosuppressant | Inhibits immunosuppressive microglia via MAPK signaling | [107] |

| Mifamurtide | Muramyl dipeptide | Enhances macrophage cytotoxicity and has been used for osteosarcoma treatment | [108] |

| Butyrate | Fatty acid | Anti-inflammatory in primary, brain-derived microglia cells, but is proinflammatory in transformed, proliferating N9 microglia | [109] |

| I-125 | Radioactive isotope | Stimulates microglia/macrophage to remove necrotic debris | [110] |

Table 2.

Molecules/targets in GAMs for therapeutic modulation.

| Molecule/agent | Classification | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSF-1R | Cytokine receptor | Inhibits glioblastoma invasion by targeting glioblastoma-associated microglia via inhibition of the CSF-1R | [16, 111] |

| TGFβ1 | Cytokine | GAMs enhance the invasion of GSCs via TGFβ1 signaling pathway, which increases the production of MMP-9 by GSCs | [77, 112] |

| IL-4 | Cytokine | Inhibits inflammatory mRNA expression in mixed rat glial and in isolated microglia cultures | [113] |

| IL-16 | Cytokine | Expression correlates with WHO grades of human astrocytic brain tumors | [114] |

| MCP-1 | Cytokine | A positive amplification circuit for macrophage recruitment in gliomas | [115] |

| Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) | Neuropeptides | Inhibit the production of inflammatory mediators by activated microglia, thus, defined as “microglia-deactivating factors” | [116] |

| STAT-3 | Transcription factor | STAT3 inhibition activates tumor macrophages and abrogates glioma growth | [44, 117–119] |

| Cyclophosphamide (CPA) | Alkylating agent | Pretreatment with CPA inhibits an increase of CD68+ and CD163+ cells and therefore enhances HSV replication and oncolysis | [120] |

| Dexamethasone | Steroid | Inhibits the filtration of microglia into brain tumors | [121] |

| ATP | Nucleotide | Promotes an anti-inflammatory state in both hematogenous and resident myeloid cells of the CNS | [122] |

| Radiochemotherapy | Therapy | Depletes CD68+ microglia | [123] |

It should be noted that glioblastoma-mediated immune suppression is notoriously heterogeneous and plastic. Thus, targeting the M2 population may only result in a therapeutic response in a subset of patients in which this mechanism is operational. Furthermore, the therapeutic response of M2 targeting may be limited when other immune suppressive mechanisms are appropriated or upregulated by the tumor. However, the suppression/inhibition of glioma-derived factors or glioma-mediated immune suppression has been shown to synergize with the efficacy of microglia therapeutic strategies [118, 126–129], suggesting that there is a therapeutic opportunity.

GAMs or their precursors could be used to facilitate CNS tumor imaging [130]. Accurate delineation of tumor margins is vital to the successful surgical resection of brain tumors and the extent of resection impacts survival. The nanoparticle CLIO-Cy5.5 is taken by microglia and is detectable by both magnetic resonance imaging and fluorescence. It could be used to assist intraoperatively in visualizing tumor boundaries because CD11b+ microglia are found at the tumor margin [131]. Other labeling system include cyclodextrin-based nanoparticles (CDP-NPs) [132] or multiwalled carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) [133]. Recently, quantum dots have been shown to be phagocytized by microglia and macrophages that infiltrate experimental gliomas that resulted in improved identification and visualization of tumors, potentially augmenting brain tumor biopsy and resection [134]. Ultimately, these imaging approaches could be exploited as biomarkers to monitor clinical trials targeting the GAM population [135].

5. Summary

The data indicates that GAMs may not solely inhibit or enhance glioma growth. Rather, the dominant propensity depends on the interacting microenvironment. It is possible that the tumor-supportive role of the microglia is unintentional—a tumor subversion of a physiological response normally used to deescalate immunological reactivity. Typically the CNS microglia are providing a surveillance function of CNS tissue, guiding the lymphocytes there and exerting their own effector functions and scavenging to wipe out glioma cells. In the early stages of gliomagenesis, innate responses mediated by microglia may be beneficial and involve the activation of effective surveillance by adaptive immunity resulting in the elimination of these cells [136]. However, in the context of progressive malignancy, when tumor cells have escaped immune editing, the smoldering inflammation orchestrated by GAMs, may promote tumor progression. Therapeutic strategies targeting macrophages should take into account the dual role of these cells.

Conflict of Interests

The authors have declared that no conflict of interests exists.

Abbreviations

- AchR:

Acetylcholine receptor

- ADCC:

Antibody dependent cell mediated cytotoxicity

- AIF-1:

Allograft inflammatory factor-1

- APC:

Antigen-presenting cell

- CpG-ODN:

CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide

- CNS:

Central nervous system

- DcR3:

Decoy receptor 3

- EC:

Endothelial cells

- EGF:

Epidermal growth factor

- GAMs:

Glioma-associated microglia/macrophages

- GSCs:

Glioma cancer stem cells

- HGF:

Hepatocyte growth factor

- HO-1:

Heme oxygenase-1

- HSV-TK:

Herpes simplex virus 1 thymidine kinase

- IL:

Interleukin

- iNOS:

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- MDSCs:

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- MHC:

Major histocompatibility complex

- MIF:

Macrophage inhibitory factor

- MMP:

Matrix metalloproteinase

- NO:

Nitric oxide

- ROS:

Reactive oxygen species

- PACAP:

Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide

- PGE2:

Prostaglandin E2

- SF:

Scatter factor

- STAT:

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TGF:

Transforming growth factor

- TLR:

Toll-like receptor

- TMZ:

Temozolomide

- TNFR:

Tumor necrosis factor-related

- Tregs:

Regulatory T cells

- VEGF:

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- VIP:

Vasoactive intestinal peptide.

References

- 1.Kettenmann H, Hanisch UK, Noda M, Verkhratsky A. Physiology of microglia. Physiological Reviews. 2011;91(2):461–553. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perry VH, Nicoll JAR, Holmes C. Microglia in neurodegenerative disease. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2010;6(4):193–201. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams KC, Hickey WF. Traffic of hematogenous cells through the central nervous system. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 1995;202:221–245. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79657-9_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010;330(6005):841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aizawa T, Haga S, Yoshikawa K. Neural differentiation-associated generation of microglia-like phagocytes in murine embryonal carcinoma cell line. Developmental Brain Research. 1991;59(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90033-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badie B, Schartner JM. Flow cytometric characterization of tumor-associated macrophages in experimental gliomas. Neurosurgery. 2000;46(4):957–962. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200004000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morimura T, Neuchrist C, Kitz K, et al. Monocyte subpopulations in human gliomas: expression of Fc and complement receptors and correlation with tumor proliferation. Acta Neuropathologica. 1990;80(3):287–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00294647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roggendorf W, Strupp S, Paulus W. Distribution and characterization of microglia/macrophages in human brain tumors. Acta Neuropathologica. 1996;92(3):288–293. doi: 10.1007/s004010050520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graeber MB, Scheithauer BW, Kreutzberg GW. Microglia in brain tumors. GLIA. 2002;40(2):252–259. doi: 10.1002/glia.10147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wierzba-Bobrowicz T, Kuchna I, Matyja E. Reaction of microglial cells in human astrocytomas (preliminary report) Folia Neuropathologica. 1994;32(4):251–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morioka T, Baba T, Black KL, Streit WJ. Response of microglial cells to experimental rat glioma. GLIA. 1992;6(1):75–79. doi: 10.1002/glia.440060110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badie B, Schartner J, Klaver J, Vorpahl J. In vitro modulation of microglia motility by glioma cells is mediated by hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor. Neurosurgery. 1999;44(5):1077–1083. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199905000-00075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okada M, Saio M, Kito Y, et al. Tumor-associated macrophage/microglia infiltration in human gliomas is correlated with MCP-3, but not MCP-1. International Journal of Oncology. 2009;34(6):1621–1627. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villeneuve J, Tremblay P, Vallières L. Tumor necrosis factor reduces brain tumor growth by enhancing macrophage recruitment and microcyst formation. Cancer Research. 2005;65(9):3928–3936. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alterman RL, Stanley ER. Colony stimulating factor-1 expression in human glioma. Molecular and Chemical Neuropathology. 1994;21(2-3):177–188. doi: 10.1007/BF02815350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coniglio SJ, Eugenin E, Dobrenis K, et al. Microglial stimulation of glioblastoma invasion involves epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF-1R) signaling. Molecular Medicine. 2012;18:519–527. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komohara Y, Ohnishi K, Kuratsu J, Takeya M. Possible involvement of the M2 anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype in growth of human gliomas. Journal of Pathology. 2008;216(1):15–24. doi: 10.1002/path.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ku MC, Wolf SA, Respondek D, et al. GDNF mediates glioblastoma-induced microglia attraction but not astrogliosis. Acta Neuropathologica. 2013;125(4):609–620. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sielska M, Przanowski P, Wylot B, et al. Distinct roles of CSF family cytokines in macrophage infiltration and activation in glioma progression and injury response. Journal of Pathology. 2013;230(3):310–321. doi: 10.1002/path.4192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frei K, Piani D, Malipiero UV, Van Meir E, De Tribolet N, Fontana A. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) production by glioblastoma cells: despite the presence of inducing signals GM-CSF is not expressed in vivo. Journal of Immunology. 1992;148(10):3140–3146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nitta T, Sato K, Allegretta M, et al. Expression of granulocyte colony stimulating factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor genes in human astrocytoma cell lines and glioma specimens. Brain Research. 1992;571(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90505-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed Z, Shaw G, Sharma VP, Yang C, McGowan E, Dickson DW. Actin-binding proteins coronin-1a and IBA-1 are effective microglial markers for immunohistochemistry. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 2007;55(7):687–700. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A7156.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoek RH, Ruuls SR, Murphy CA, et al. Down-regulation of the macrophage lineage through interaction with OX2 (CD200) Science. 2000;290(5497):1768–1771. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo LH, Trautmann K, Schluesener HJ. Expression of P2X4 receptor in rat C6 glioma by tumor-associated macrophages and activated microglia. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2004;152(1-2):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deininger MH, Meyermann R, Trautmann K, et al. Heme oxygenase (HO)-1 expressing macrophages/microglial cells accumulate during oligodendroglioma progression. Brain Research. 2000;882(1-2):1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02594-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deininger MH, Seid K, Engel S, Meyermann R, Schluesener HJ. Allograft inflammatory factor-1 defines a distinct subset of infiltrating macrophages/microglial cells in rat and human gliomas. Acta Neuropathologica. 2000;100(6):673–680. doi: 10.1007/s004010000233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Badie B, Schartner J. Role of microglia in glioma biology. Microscopy Research and Technique. 2001;54(2):106–113. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ford AL, Goodsall AL, Hickey WF, Sedgwick JD. Normal adult ramified microglia separated from other central nervous system macrophages by flow cytometric sorting: phenotypic differences defined and direct ex vivo antigen presentation to myelin basic protein-reactive CD4+ T cells compared. Journal of Immunology. 1995;154(9):4309–4321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sedgwick JD, Schwender S, Imrich H, Dorries R, Butcher GW, Ter Meulen V. Isolation and direct characterization of resident microglial cells from the normal and inflamed central nervous system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88(16):7438–7442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2012;12(4):253–268. doi: 10.1038/nri3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Umemura N, Saio M, Suwa T, et al. Tumor-infiltrating myeloid-derived suppressor cells are pleiotropic-inflamed monocytes/macrophages that bear M1- and M2-type characteristics. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2008;83(5):1136–1144. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Badie B, Schartner J, Prabakaran S, Paul J, Vorpahl J. Expression of Fas ligand by microglia: possible role in glioma immune evasion. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2001;120(1-2):19–24. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hussain SF, Yang D, Suki D, Aldape K, Grimm E, Heimberger AB. The role of human glioma-infiltrating microglia/macrophages in mediating antitumor immune responses. Neuro-Oncology. 2006;8(3):261–279. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2006-008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jia W, Jackson-Cook C, Graf MR. Tumor-infiltrating, myeloid-derived suppressor cells inhibit T cell activity by nitric oxide production in an intracranial rat glioma+vaccination model. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2010;223(1-2):20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez FO, Sica A, Mantovani A, Locati M. Macrophage activation and polarization. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2008;13(2):453–461. doi: 10.2741/2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2004;4(1):71–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gabrusiewicz K, Ellert-Miklaszewska A, Lipko M, Sielska M, Frankowska M, Kaminska B. Characteristics of the alternative phenotype of microglia/macrophages and its modulation in experimental gliomas. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023902.e23902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei J, Barr J, Kong LY, et al. Glioma-associated cancer-initiating cells induce immunosuppression. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16(2):461–473. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 39.Zou JP, Morford LA, Chougnet C, et al. Human glioma-induced immunosuppression involves soluble factor(s) that alters monocyte cytokine profile and surface markers. Journal of Immunology. 1999;162(8):4882–4892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bach JP, Deuster O, Balzer-Geldsetzer M, Meyer B, Dodel R, Bacher M. The role of macrophage inhibitory factor in tumorigenesis and central nervous system tumors. Cancer. 2009;115(10):2031–2040. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Charles NA, Holland EC, Gilbertson R, Glass R, Kettenmann H. The brain tumor microenvironment. GLIA. 2011;59(8):1169–1180. doi: 10.1002/glia.21136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiu B, Zhang D, Wang C, et al. IL-10 and TGF-β2 are overexpressed in tumor spheres cultured from human gliomas. Molecular Biology Reports. 2011;38(5):3585–3591. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0469-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang L, Handel MV, Schartner JM, et al. Regulation of IL-10 expression by upstream stimulating factor (USF-1) in glioma-associated microglia. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2007;184(1-2):188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu A, Wei J, Kong LY, et al. Glioma cancer stem cells induce immunosuppressive macrophages/microglia. Neuro-Oncology. 2010;12(11):1113–1125. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sica A, Schioppa T, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages are a distinct M2 polarised population promoting tumour progression: potential targets of anti-cancer therapy. European Journal of Cancer. 2006;42(6):717–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gomez GG, Kruse CA. Mechanisms of malignant glioma immune resistance and sources of immunosuppression. Gene Therapy and Molecular Biology. 2006;10(1):133–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kren L, Muckova K, Lzicarova E, et al. Production of immune-modulatory nonclassical molecules HLA-G and HLA-E by tumor infiltrating ameboid microglia/macrophages in glioblastomas: a role in innate immunity? Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2010;220(1-2):131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kennedy BC, Maier LM, D’Amico R, et al. Dynamics of central and peripheral immunomodulation in a murine glioma model. BMC Immunology. 2009;10(article 11) doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He BP, Wang JJ, Zhang X, et al. Differential reactions of microglia to brain metastasis of lung cancer. Molecular Medicine. 2006;12(7-8):161–170. doi: 10.2119/2006-00033.He. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pukrop T, Dehghani F, Chuang HN, et al. Microglia promote colonization of brain tissue by breast cancer cells in a Wnt-dependent way. GLIA. 2010;58(12):1477–1489. doi: 10.1002/glia.21022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hussain SF, Yang D, Suki D, Grimm E, Heimberger AB. Innate immune functions of microglia isolated from human glioma patients. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2006;4(article 15) doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schartner JM, Hagar AR, Van Handel M, Zhang L, Nadkarni N, Badie B. Impaired capacity for upregulation of MHC class II in tumor-associated microglia. GLIA. 2005;51(4):279–285. doi: 10.1002/glia.20201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mora R, Régnier-Vigouroux A. Autophagy-driven cell fate decision maker: activated microglia induce specific death of glioma cells by a blockade of basal autophagic flux and secondary apoptosis/necrosis. Autophagy. 2009;5(3):419–421. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.3.7881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bright JJ, Natarajan C, Sriram S, Muthian G. Signaling through JAK2-STAT5 pathway is essential for IL-3-induced activation of microglia. GLIA. 2004;45(2):188–196. doi: 10.1002/glia.10316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Askew D, Walker WS. Alloantigen presentation to naive CD8+ T cells by mouse microglia: evidence for a distinct phenotype based on expression of surface-associated and soluble costimulatory molecules. GLIA. 1996;18(2):118–128. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199610)18:2<118::AID-GLIA4>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nishie A, Ono M, Shono T, et al. Macrophage infiltration and heme oxygenase-1 expression correlate with angiogenesis in human gliomas. Clinical Cancer Research. 1999;5(5):1107–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mariani CL, Kouri JG, Streit WJ. Rejection of RG-2 gliomas is mediated by microglia and T lymphocytes. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2006;79(3):243–253. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watanabe T, Tanaka R, Taniguchi Y, Yamamoto K, Ono K, Yoshida S. The role of microglia and tumor-primed lymphocytes in the interaction between T lymphocytes and brain endothelial cells. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 1998;81(1-2):90–97. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sutter A, Hekmat A, Luckenbach GA. Antibody-mediated tumor cytotoxicity of microglia. Pathobiology. 1991;59(4):254–258. doi: 10.1159/000163657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Synowitz M, Glass R, Färber K, et al. A1 adenosine receptors in microglia control glioblastoma-host interaction. Cancer Research. 2006;66(17):8550–8557. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Färber K, Synowitz M, Zahn G, et al. An α5β1 integrin inhibitor attenuates glioma growth. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2008;39(4):579–585. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Markovic DS, Vinnakota K, Chirasani S, et al. Gliomas induce and exploit microglial MT1-MMP expression for tumor expansion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(30):12530–12535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804273106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Markovic DS, Glass R, Synowitz M, Van Rooijen N, Kettenmann H. Microglia stimulate the invasiveness of glioma cells by increasing the activity of metalloprotease-2. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2005;64(9):754–762. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000178445.33972.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Held-Feindt J, Hattermann K, Müerköster SS, et al. CX3CR1 promotes recruitment of human glioma-infiltrating microglia/macrophages (GIMs) Experimental Cell Research. 2010;316(9):1553–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.da Fonseca ACC, Romão L, Amaral RF, et al. Microglial stress inducible protein 1 promotes proliferation and migration in human glioblastoma cells. Neuroscience. 2012;200:130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lull ME, Block ML. Microglial activation and chronic neurodegeneration. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7(4):354–365. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Doucette TA, Kong LY, Yang Y, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 promotes angiogenesis and drives malignant progression in glioma. Neuro-Oncology. 2012;14(9):1136–1145. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bezzi P, Domercq M, Brambilla L, et al. CXCR4-activated astrocyte glutamate release via TNFa: amplification by microglia triggers neurotoxicity. Nature Neuroscience. 2001;4(7):702–710. doi: 10.1038/89490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Deininger MH, Schluesener HJ. Cyclooxygenases-1 and -2 are differentially localized to microglia and endothelium in rat EAE and glioma. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 1999;95(1-2):202–208. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Deininger MH, Meyermann R, Trautmann K, et al. Cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 expressing macrophages/microglial cells and COX-2 expressing astrocytes accumulate during oligodendroglioma progression. Brain Research. 2000;885(1):111–116. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02978-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Temel SG, Kahveci Z. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in astrocytes and microglia in human oligodendroglioma and astrocytoma. Journal of Molecular Histology. 2009;40(5-6):369–377. doi: 10.1007/s10735-009-9250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Daginakatte GC, Gianino SM, Zhao NW, Parsadanian AS, Gutmann DH. Increased c-Jun-NH2-kinase signaling in neurofibromatosis-1 heterozygous microglia drives microglia activation and promotes optic glioma proliferation. Cancer Research. 2008;68(24):10358–10366. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Daginakatte GC, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis-1 (Nf1) heterozygous brain microglia elaborate paracrine factors that promote Nf1-deficient astrocyte and glioma growth. Human Molecular Genetics. 2007;16(9):1098–1112. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Butovsky O, Ziv Y, Schwartz A, et al. Microglia activated by IL-4 or IFN-γ differentially induce neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis from adult stem/progenitor cells. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2006;31(1):149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444(7120):756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yi L, Xiao H, Xu M, et al. Glioma-initiating cells: a predominant role in microglia/macrophages tropism to glioma. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2011;232(1-2):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ye XZ, Xu SL, Xin YH, et al. Tumor-associated microglia/macrophages enhance the invasion of glioma stem-like cells via TGF-beta1 signaling pathway. Journal of Immunology. 2012;189(1):444–453. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Morantz RA, Wood GW, Foster M. Macrophages in experimental and human brain tumors. Part I. Studies of the macrophage content of experimental rat brain tumors of varying immunogenicity. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1979;50(3):298–304. doi: 10.3171/jns.1979.50.3.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Badie B, Bartley B, Schartner J. Differential expression of MHC class II and B7 costimulatory molecules by microglia in rodent gliomas. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2002;133(1-2):39–45. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00350-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Voisin P, Bouchaud V, Merle M, et al. Microglia in close vicinity of glioma cells: correlation between phenotype and metabolic alterations. Front Neuroenergetics. 2010;2(article 131) doi: 10.3389/fnene.2010.00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fang KM, Wang YL, Huang MC, Sun SH, Cheng H, Tzeng SF. Expression of macrophage inflammatory protein-1α and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in glioma-infiltrating microglia: involvement of ATP and P2X7 receptor. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2011;89(2):199–211. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Engel S, Isenmann S, Ständer M, Rieger J, Bähr M, Weller M. Inhibition of experimental rat glioma growth by decorin gene transfer is associated with decreased microglial infiltration. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 1999;99(1):13–18. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhai H, Heppner FL, Tsirka SE. Microglia/macrophages promote glioma progression. GLIA. 2011;59(3):472–485. doi: 10.1002/glia.21117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nagai T, Tanaka M, Tsuneyoshi Y, et al. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages in an experimental glioma model with a recombinant immunotoxin to folate receptor beta. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2009;58(10):1577–1586. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0667-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Barba D, Hardin J, Sadelain M, Gage FH. Development of anti-tumor immunity following thymidine kinase-mediated killing of experimental brain tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(10):4348–4352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fulci G, Dmitrieva N, Gianni D, et al. Depletion of peripheral macrophages and brain microglia increases brain tumor titers of oncolytic viruses. Cancer Research. 2007;67:9398–9406. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carpentier AF, Xie J, Mokhtari K, Delattre JY. Successful treatment of intracranial gliomas in rat by oligodeoxynucleotides containing CpG motifs. Clinical Cancer Research. 2000;6(6):2469–2473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dalpke AH, Scháfer MKH, Frey M, et al. Immunostimulatory CpG-DNA activates murine microglia. Journal of Immunology. 2002;168(10):4854–4863. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.4854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.El Andaloussi A, Sonabend AM, Han Y, Lesniak MS. Stimulation of TLR9 with CpG ODN enhances apoptosis of glioma and prolongs the survival of mice with experimental brain tumors. GLIA. 2006;54(6):526–535. doi: 10.1002/glia.20401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kees T, Lohr J, Noack J, et al. Microglia isolated from patients with glioma gain antitumor activities on poly (I:C) stimulation. Neuro-Oncology. 2012;14(1):64–78. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chiu TL, Peng CW, Wang MJ. Enhanced anti-glioblastoma activity of microglia by AAV2-mediated IL-12 through TRAIL and phagocytosis in vitro. Oncology Reports. 2011;25(5):1373–1380. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chiu TL, Wang MJ, Su CC. The treatment of glioblastoma multiforme through activation of microglia and TRAIL induced by rAAV2-mediated IL-12 in a syngeneic rat model. Journal of Biomedical Science. 2012;19(article 45) doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-19-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nakagawa J, Saio M, Tamakawa N, et al. TNF expressed by tumor-associated macrophages, but not microglia, can eliminate glioma. International Journal of Oncology. 2007;30(4):803–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dutta T, Spence A, Lampson LA. Robust ability of IFN-γ to upregulate class II MHC antigen expression in tumor bearing rat brains. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2003;64(1-2):31–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02700018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kulprathipanja NV, Kruse CA. Microglia phagocytose alloreactive CTL-damaged 9L gliosarcoma cells. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2004;153(1-2):76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lauterbach H, Zuniga EI, Truong P, Oldstone MBA, McGavern DB. Adoptive immunotherapy induces CNS dendritic cell recruitment and antigen presentation during clearance of a persistent viral infection. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2006;203(8):1963–1975. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Färber K, Cheung G, Mitchell D, et al. C1q, the recognition subcomponent of the classical pathway of complement, drives microglial activation. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2009;87(3):644–652. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schafer DP, Lehrman EK, Kautzman AG, et al. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron. 2012;74(4):691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Begum Z, Ghosh A, Sarkar S, et al. Documentation of immune profile of microglia through cell surface marker study in glioma model primed by a novel cell surface glycopeptide T11TS/SLFA-3. Glycoconjugate Journal. 2004;20(9):515–523. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000043287.98081.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sarkar S, Ghosh A, Mukherjee J, Chaudhuri S, Chaudhuri S. CD2-SLFA3/T11TS interaction facilitates immune activation and glioma regression by apoptosis. Cancer Biology and Therapy. 2004;3(11):1121–1128. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.11.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nakajima K, Tohyama Y, Kohsaka S, Kurihara T. Ceramide activates microglia to enhance the production/secretion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) without induction of deleterious factors in vitro. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2002;80(4):697–705. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Min KJ, Pyo HK, Yang MS, Ji KA, Jou I, Joe EH. Gangliosides activate microglia via protein kinase C and NADPH oxidase. GLIA. 2004;48(3):197–206. doi: 10.1002/glia.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Takahashi K, Rochford CDP, Neumann H. Clearance of apoptotic neurons without inflammation by microglial triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;201(4):647–657. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ryu J, Min KJ, Rhim TY, et al. Prothrombin kringle-2 activates cultured rat brain microglia. Journal of Immunology. 2002;168(11):5805–5810. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jacobs VL, Landry RP, Liu Y, Romero-Sandoval EA, De Leo JA. Propentofylline decreases tumor growth in a rodent model of glioblastoma multiforme by a direct mechanism on microglia. Neuro-Oncology. 2012;14(2):119–131. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Markovic DS, Vinnakota K, van Rooijen N, et al. Minocycline reduces glioma expansion and invasion by attenuating microglial MT1-MMP expression. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2011;25(4):624–628. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sliwa M, Markovic D, Gabrusiewicz K, et al. The invasion promoting effect of microglia on glioblastoma cells is inhibited by cyclosporin A. Brain. 2007;130(part 2):476–489. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Meyers PA, Schwartz CL, Krailo MD, et al. Osteosarcoma: the addition of muramyl tripeptide to chemotherapy improves overall survival—a report from the children’s oncology group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(4):633–638. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.14.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Huuskonen J, Suuronen T, Nuutinen T, Kyrylenko S, Salminen A. Regulation of microglial inflammatory response by sodium butyrate and short-chain fatty acids. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2004;141(5):874–880. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Julow J, Szeifert GT, Bálint K, Nyáry I, Nemes Z. The role of microglia/macrophage system in the tissue response to I-125 interstitial brachytherapy of cerebral gliomas. Neurological Research. 2007;29(3):233–238. doi: 10.1179/016164107X158875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lodge PA, Sriram S. Regulation of microglial activation by TGF-β, IL-10, and CSF-1. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 1996;60(4):502–508. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.4.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wesolowska A, Kwiatkowska A, Slomnicki L, et al. Microglia-derived TGF-β as an important regulator of glioblastoma invasion—an inhibition of TGF-β-dependent effects by shRNA against human TGF-β type II receptor. Oncogene. 2008;27(7):918–930. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kitamura Y, Taniguchi T, Kimura H, Nomura Y, Gebicke-Haerter PJ. Interleukin-4-inhibited mRNA expression in mixed rat glial and in isolated microglial cultures. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2000;106(1-2):95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Liebrich M, Guo LH, Schluesener HJ, et al. Expression of interleukin-16 by tumor-associated macrophages/activated microglia in high-grade astrocytic brain tumors. Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis. 2007;55(1):41–47. doi: 10.1007/s00005-007-0003-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Leung SY, Wong MP, Chung LP, Chan ASY, Yuen ST. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression and macrophage infiltration in gliomas. Acta Neuropathologica. 1997;93(5):518–527. doi: 10.1007/s004010050647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Delgado M, Leceta J, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide inhibit the production of inflammatory mediators by activated microglia. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2003;73(1):155–164. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0702372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hussain SF, Kong LY, Jordan J, et al. A novel small molecule inhibitor of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 reverses immune tolerance in malignant glioma patients. Cancer Research. 2007;67(20):9630–9636. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhang L, Alizadeh D, van Handel M, Kortylewski M, Yu H, Badie B. Stat3 inhibition activates tumor macrophages and abrogates glioma growth in mice. GLIA. 2009;57(13):1458–1467. doi: 10.1002/glia.20863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhang L, Liu W, Alizadeh D, et al. S100B attenuates microglia activation in gliomas: possible role of STAT3 pathway. GLIA. 2011;59(3):486–498. doi: 10.1002/glia.21118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Fulci G, Breymann L, Gianni D, et al. Cyclophosphamide enhances glioma virotherapy by inhibiting innate immune responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(34):12873–12878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605496103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Badie B, Schartner JM, Paul J, Bartley BA, Vorpahl J, Preston JK. Dexamethasone-induced abolition of the inflammatory response in an experimental glioma model: a flow cytometry study. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2000;93(4):634–639. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.4.0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lambert C, Ase AR, Séguéla P, Antel JP. Distinct migratory and cytokine responses of human microglia and macrophages to ATP. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2010;24(8):1241–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Deininger MH, Pater S, Strik H, Meyermann R. Macrophage/microglial cell subpopulations in glioblastoma multiforme relapses are differentially altered by radiochemotherapy. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2001;55(3):141–147. doi: 10.1023/a:1013805915224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kim SS, Ye C, Kumar P, et al. Targeted delivery of sirna to macrophages for anti-inflammatory treatment. Molecular Therapy. 2010;18(5):993–1001. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Weingart JD, Sipos EP, Brem H. The role of minocycline in the treatment of intracranial 9L glioma. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1995;82(4):635–640. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.4.0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ghosh A, Mukherjee J, Bhattacharjee M, et al. The other side of the coin: beneficiary effect of ’oxidative burst’ upsurge with T11TS facilitates the elimination of glioma cells. Cellular and Molecular Biology. 2007;53(5):53–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hwang SY, Yoo BC, Jung JW, et al. Induction of glioma apoptosis by microglia-secreted molecules: the role of nitric oxide and cathepsin B. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1793(11):1656–1668. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kim YJ, Hwang SY, Hwang JS, Lee JW, Oh ES, Han IO. C6 glioma cell insoluble matrix components enhance interferon-γ-stimulated inducible nitric-oxide synthase/nitric oxide production in BV2 microglial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(5):2526–2533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kim YJ, Hwang SY, Oh ES, Oh S, Han IO. IL-1β, an immediate early protein secreted by activated microglia, induces iNOS/NO in C6 astrocytoma cells through p38 MAPK and NF-κB pathways. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2006;84(5):1037–1046. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ribot E, Bouzier-Sore AK, Bouchaud V, et al. Microglia used as vehicles for both inducible thymidine kinase gene therapy and MRI contrast agents for glioma therapy. Cancer Gene Therapy. 2007;14(8):724–737. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7701060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Tréhin R, Figueiredo JL, Pittet MJ, Weissleder R, Josephson L, Mahmood U. Fluorescent nanoparticle uptake for brain tumor visualization. Neoplasia. 2006;8(4):302–311. doi: 10.1593/neo.05751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Alizadeh D, Zhang L, Hwang J, Schluep T, Badie B. Tumor-associated macrophages are predominant carriers of cyclodextrin-based nanoparticles into gliomas. Nanomedicine. 2010;6(2):382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kateb B, Van Handel M, Zhang L, Bronikowski MJ, Manohara H, Badie B. Internalization of MWCNTs by microglia: possible application in immunotherapy of brain tumors. NeuroImage. 2007;37(supplement 1):S9–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Jackson H, Muhammad O, Daneshvar H, et al. Quantum dots are phagocytized by macrophages and colocalize with experimental gliomas. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(3):524–529. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000255334.95532.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Fleige G, Nolte C, Synowitz M, Seeberger F, Kettenmann H, Zimmer C. Magnetic labeling of activated microglia in experimental gliomas. Neoplasia. 2001;3(6):489–499. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Smyth MJ, Dunn GP, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting: the roles of immunity in suppressing tumor development and shaping tumor immunogenicity. Advances in Immunology. 2006;90:1–50. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)90001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]