Abstract

The right-sided aorta associated with an aberrant left subclavian artery is a rare anomaly of the aortic branches in the upper mediastinum. We present a 62-year-old patient suffering from an acute dissection of the ascending aorta associated with hemopericardium. In this case, there was also aneurysmal dilatation of the origin of the left subclavian artery, known as diverticulum of Kommerell.

Keywords: CT angiography, thorax, vascular, CT, aorta, esophagus

A right-sided aortic arch is a rare congenital abnormality of the aorta and the aortic branches in the upper mediastinum (prevalence of 0.5% in the normal population (1)). The left subclavian artery arises from the descending aorta and is intersecting posterior of the esophagus, anterior of the trachea or between them. In the adult population, this aberrant pathway of the subclavian artery shows miscellaneous symptoms like dysphagia (“dysphagia lusoria”), respiratory symptoms like wheezing, cough, choking spells, and obstructive emphysema. Aneurysmatic dilatation of the vascular origin of the aberrant subclavian artery is named after a German radiologist, Dr Kommerell, who first described this special vascular constellation. The coincidence with a right-sided aortic arch is reported to be 50% (2, 3). The most severe complication is an aneurysmal rupture of the Kommerell diverticulum with almost certain fatal mediastinal hemorrhage (4). Further complications include dissection and recurrent pneumonia.

Case report

A 62-year-old female patient arrived at our emergency department after collapsing during her household routine. After intubation, peripheral oxygenation decreased to 59%, followed by bradycardia and low blood pressure. Fifteen minutes later, the patient developed a cardiac arrest. The patient was stabilized with 3 mg of atropine and 4 mg of adrenaline. Cranial computed tomography (CCT) with perfusion imaging at the level of the basal ganglia and carotid CT angiography (120 kVp, 95 mAs, pitch of 1.2, standard image reconstruction in 0.6 mm thickness, and multiplanar reconstructions in 5 mm thickness for the carotid artery) was performed to exclude intracranial bleeding, ischemic stroke, and carotid obstruction. CT images showed no signs of intracranial or cervical pathology. However, the upper mediastinum was seen markedly enlarged. Therefore, CT angiography with coronal and sagittal reconstructions of the thoracic aorta was appended (100 kVp, 150 mAs, pitch of 1.25, 1.5, and 5 mm reconstructions). We found a complex vascular anomaly of the aorta and the supra-aortic branches with right-sided aortic arch and aneurysmal dilatation of the vascular origin of the aberrant left subclavian artery (Figs. 1–4). Furthermore, there was a dense pericardial effusion (45 HU), strongly indicating a dissection of the ascending aorta including a hemopericardium. Due to motion artifacts at the level of the aortic root, no intimal flap was evident (Fig. 5a). Further electrocardiography-triggered CT of the thorax revealed a dissection of the aorta type A following the Stanford classification (DeBakey type II) with pericardial tamponade (Fig. 5b). Surgery with graft replacement was performed immediately. Because of the long-lasting, cerebral perfusion deficiency, the patient developed a massive cerebral ischemia with associated edema 3 days after surgery. On a follow-up CT, there was brain swelling with loss of differentiation of the cortex. The patient died 4 days after the initial event.

Fig. 2.

Maximum intensity projection (MIP) of chest CT after contrast injection. Maximum diameter of the aneurysm at the aberrant origin of the left subclavian artery is 3.3 cm (white arrows). The black arrow points at the aortic arch with a prominent brachiocephalic trunk (black arrowhead). Note hemopericardium (asterisk)

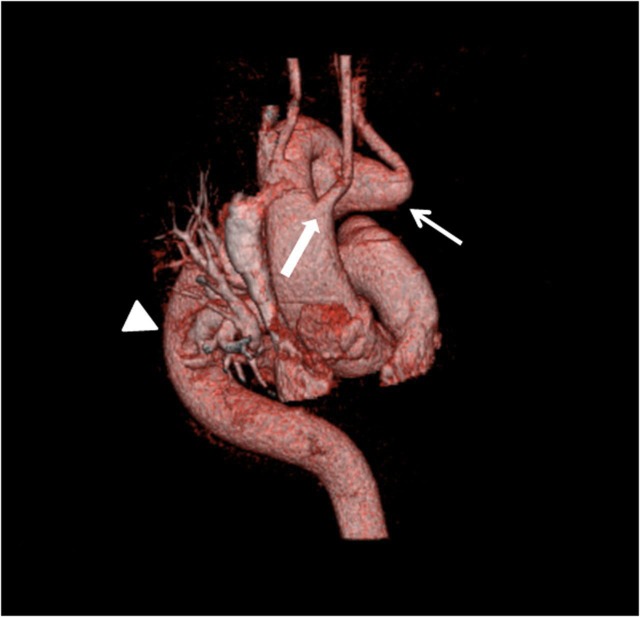

Fig. 3.

Volume-rendering image clearly shows the Kommerell diverticulum (thin, white arrow). Note the left common carotid artery arising from the ascending aorta (white block arrow). The arrowhead points to the right-sided descending aorta

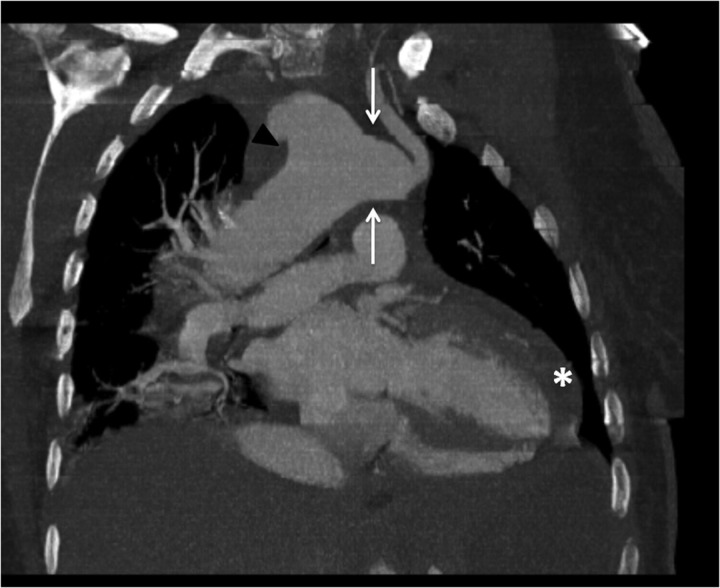

Fig. 1.

Maximum intensity projection (MIP) of chest CT after contrast injection. Origin of the left common carotid artery, arising from the ascending aorta as the first branch of the aortic arch (black arrow) and partial view of the Kommerell diverticulum with kinking of the normal-sized distal left subclavian artery (white arrow) are seen. Note the dense pericardial effusion due to pericardial hemorrhage (asterisk)

Fig. 4.

Kommerell diverticulum (asteriks) with tracheal narrowing

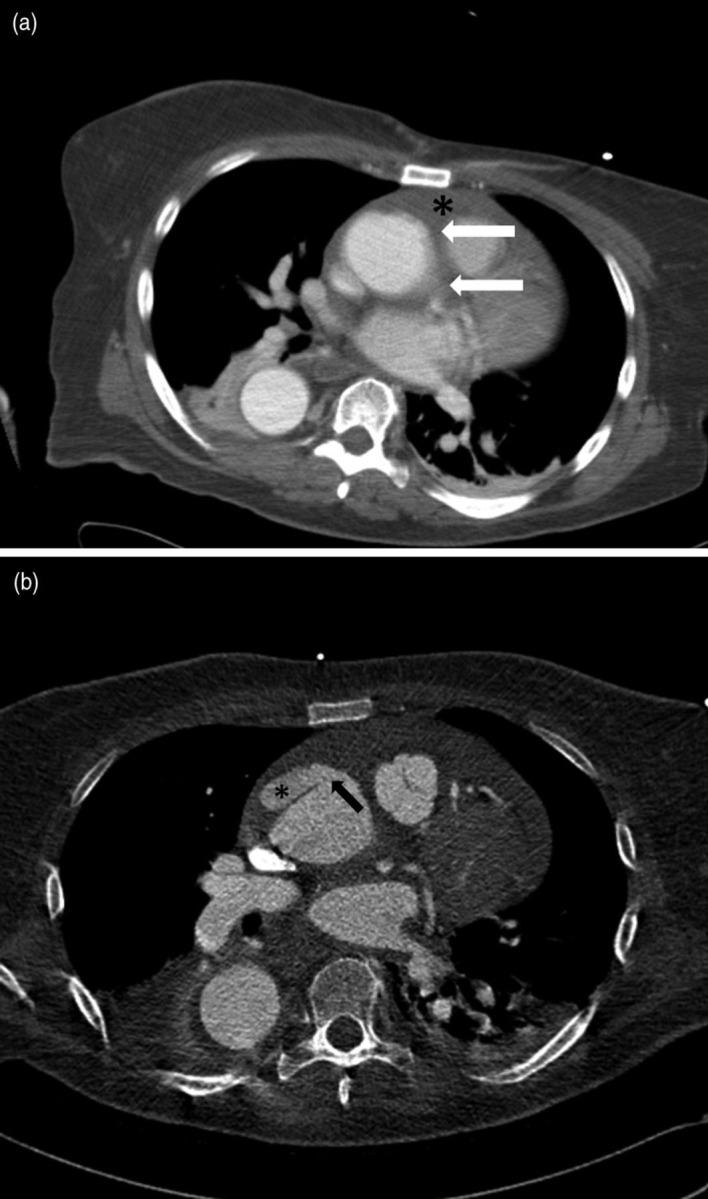

Fig. 5.

Chest CT of ascending aorta. (a) Chest CT at the level of the aortic root (without ECG triggering). Motion artefacts at the aortic root (white arrows) without evidence of aortic dissection. Note hemopericardium (black asterisk). (b) ECG-triggered study at the same level shows dissection of the ascending aorta (black asterisk) with no evidence of active bleeding. The black arrow points to the entry of the dissection

Discussion

Angiogenesis of the aorta and the aortic branches starts between the fourth and seventh week of pregnancy. Six pairs of aortic segments develop and the third pair forms the common and internal carotid arteries. The fourth segment on the left persists to develop the adult aortic arch. The other segments obliterate. Persistence of the fourth arch on the right results in the constellation of an arcus aortae dexter. On the other hand, the corresponding segment on the left disappears. A preservation of both aortic segments results in an aortic ring. Those aortic rings are usually diagnosed in infancy because of airway obstruction or difficulties in swallowing. In the common type II right-sided aortic arch (Table 1, Fig. 6) the left subclavian artery has to intersect the mediastinal structures. In 80%, the vessel transverse the mediastinum behind the esophagus; in 15%, between trachea and esophagus; and in only 5%, in front of the trachea (5–7). Although the underlying cause of persisting right-sided arch is not completely known so far, in 24% a deletion of chromosome 22q 11 is associated (8). In 75–85% of the cases with mirror arch (Edwards type I) and Edwards type III constellation, there are additional cardiac anomalies like tetralogy of Fallot, pulmonary artery stenosis in combination with septum defect, tricuspid valve atresia, or a common arterial trunk; Edwards type II reveals cardiac anomalies in only 5–10% (8). Congenital cardiac anomalies are usually diagnosed in newborns and children, they rarely become symptomatic in adults. Besides aneurysmal bleeding, patients with Kommerell diverticula present with non-specific symptoms. Vascular compression of the esophagus causes dysphagia; tracheal narrowing leads to dyspnea, recurrent tracheobronchial infections, or even asthma-like symptoms. Furthermore, the space-occupying aneurysm may present with syncope and left subclavian steal syndrome (9). There is a wide range of clinical appearances and differential diagnosis with delay in the correct diagnosis. In the presented case, acute dissection of the ascending aorta revealed this vascular anatomy in the upper mediastinum. This particular patient never suffered from the above-mentioned symptoms.

Table 1.

Edwards classification of right-sided aortic arch (6)

| Type | Definition | Prevalence(%) |

|---|---|---|

| I | Mirror image aortic arch | 59 |

| II | Aberrant left subclavian artery | 39.5 |

| III | Obliteration of the left sublavian artery with collateralization via persistent ductus arteriosus Botalli | 1.5 |

Fig. 6.

Classification according to Edwards

References

- 1. Freedom RM, Culham J, Moes C Vascular rings and associated anomalies. In: Freedom RM, Culham J, Moes C, Angiocardiography of Congential Heart Disease. New York, NY: SAGE Publications, 1984:487–498 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Son J, Julsrud PR, Hagler DJ, et al. Surgical treatment of vascular rings: The Mayo Clinic experience. Mayo Clin Proc 1993;68:1056–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morel V, Corbineau H, Lecoz A, et al. Two cases of asthma revealing a diverticulum of Kommerell. Respiration 2002;69:456–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fisher RG, Whigham CJ, Trinh C Diverticula of Kommerell and aberrant subclavian arteries complicated by aneurysms. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2005;28:553–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gomes MM, Bernatz PE, Forth RJ Arteriosclerotic aneurysm of an aberrant right subclavian artery. Dis Chest 1968;54:549–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Edwards JE Anomalies of the derivates of the aortic arch system. Med Clin N Am 1948;32:925–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Takeyoshi O, Kenji O, Shuichiro T, et al. Surgical treatment for Kommerell's diverticulum. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;131:574–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cinà CS, Althani H, Pasenau J, et al. Kommerell's diverticulum and right-sided aortic arch: A cohort study and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg 2004;39:131–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang MH, Weng ZC, Weng YG, et al. A right-sided aortic arch with Kommerell's diverticulum of the aberrant left subclavian artery presenting with syncope. J Chin Med Assoc 2009;72:275–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]