Abstract

Background

Canadian data on the characteristics, management and outcomes of patients with transient ischemic attack (TIA) are lacking. We studied prospectively a cohort of consecutive patients presenting with TIA to the emergency department of 4 regional stroke centres in Ontario.

Methods

Using data from the Ontario Stroke Registry linked with provincial administrative databases, we determined the short-term outcomes after TIA and assessed patient management in the emergency department and within 30 days after the index TIA. We compared the TIA patients with a cohort of patients who had ischemic stroke.

Results

Three-quarters of the TIA patients were discharged from the emergency department. After discharge, the 30-day stroke risk was 5% (13/265) overall and 8% (13/167) among those with a first-ever TIA; the 30-day risk of stroke or death was 9% (11/127) among the TIA patients with a speech deficit and 12% (9/76) among those with a motor deficit. Half of the cases of stroke occurred within the first 2 days after the TIA. Diagnostic investigations were underused in hospital and on an outpatient basis within 30 days after the index TIA, the rates being as follows: CT scanning, 58% (211/364); carotid Doppler ultrasonography, 44% (162/364); echocardiography, 19% (70/364); cerebral angiography, 5% (19/364); and MRI, 3% (11/364). Antithrombotic therapy was not prescribed for more than one-third of the patients at discharge. Carotid endarterectomy was performed in 2% within 90 days.

Interpretation

Patients in whom TIA is diagnosed in the emergency department have high immediate and short-term risks of stroke. However, their condition is underinvestigated and undertreated compared with stroke: many do not receive the minimum recommended diagnostic tests within 30 days. We need greater efforts to improve the timely delivery of care for TIA patients, along with investigation of treatments administered early after TIA to prevent stroke.

Transient ischemic attack (TIA) precedes 15% of stroke cases and represents a special opportunity for preventive intervention. Despite published recommendations,1,2,3,4,5 management of TIA in clinical practice is variable and often suboptimal.6,7,8,9 According to Goldstein and colleagues,10 one-third of patients presenting to a primary care office with a first-ever TIA or minor stroke did not receive diagnostic investigations or hospitalization within 1 month. Patients and physicians may underestimate the serious nature of TIA or the need for prompt evaluation and treatment.7,9,11

We studied a consecutive series of patients with an emergency department diagnosis of TIA at 4 regional centres participating in the Ontario Stroke Registry. Through links with provincial administrative databases, we evaluated the short-term outcomes after TIA as well as the patterns of practice and resource use in the management of TIA.

Methods

The Ontario Stroke Registry was established by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario as part of the evaluation of the Ontario Coordinated Stroke Strategy, an initiative aiming to coordinate and optimize stroke care across the province.12 Ontario, with a population of 11.5 million people, has universal-access, government-funded coverage of the costs of physician visits, hospital care and diagnostic tests for all residents. Four acute tertiary care centres, representing different geographic regions of the province, participated in the registry. The registry prospectively identified consecutive patients with cerebrovascular disease who presented to the emergency department of these institutions from May to December 2000.

The current analysis included only patients with TIA or ischemic stroke. Patients with intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage were not included. The TIA cohort consisted of all patients who received a most responsible diagnosis of TIA (neurologic deficit lasting less than 24 hours) within 24 hours after arrival at the emergency department, as specified by the attending physician. All patients with a diagnosis of ischemic stroke were considered separately, as a comparison group.

Data were collected at each site by a research nurse, who identified eligible patients, performed chart abstraction, interviewed care providers to obtain data on patient demographics and medical history, and tracked patients until discharge or day 30 of hospital admission. An operations manual provided instructions for chart abstraction and entry of data into the Ontario Stroke Registry.13 The registry included information on neurologic symptoms and signs, prehospital care, emergency department care, in-hospital treatment, medication prescriptions, in-hospital investigations, in-hospital complications and discharge status. Interrater reliability of chart abstraction for key variables in 120 patients was substantial to excellent (kappa or Pearson correlation coefficient 0.66 to 1.0).14

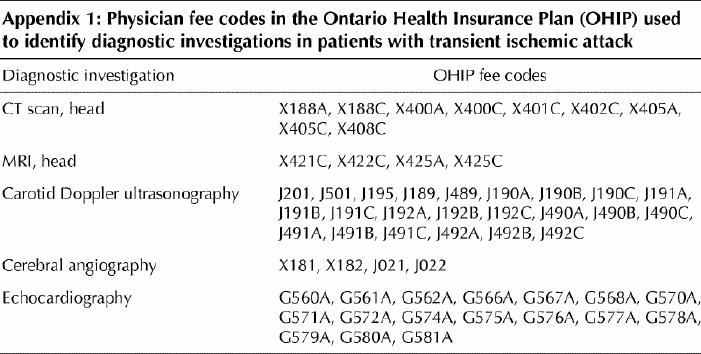

The registry was linked with provincial administrative databases by unique anonymous patient identifiers to obtain longitudinal data on hospital readmission, out-of-hospital death, and use of certain diagnostic and treatment procedures. The Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) database contains data on all patients admitted to Ontario hospitals and uses the coding system of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision.15 We documented readmissions in which the most responsible diagnosis was acute ischemic stroke (occlusion of cerebral arteries [ICD-9 code 434]) or acute but ill-defined cerebrovascular disease (436) within 90 days after the index TIA; we did not include ICD-9 code 433, because it has been shown to have poor validity.16 Out-of-hospital mortality data were obtained from the Ontario Registered Persons Data Base. Diagnostic investigations performed on an outpatient basis within 30 days after the index TIA were captured by links to the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) database of physician fee codes (Appendix 1).

Main outcomes were the proportion of TIA patients readmitted with an ischemic stroke and the proportions receiving in-hospital and outpatient investigations (CT scanning, MRI, carotid Doppler ultrasonography, cerebral angiography and echocardiography), specialty consultations, carotid endarterectomy and certain medications at discharge (ASA, ticlopidine, clopidogrel, warfarin, lipid-lowering drugs, angiotensin-converting-enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, β-blockers, calcium-channel blockers and diuretics). Secondary analyses compared the management of TIA and ischemic stroke. Student's t test was used to compare continuous variables and the χ2 test to compare categorical variables.

Results

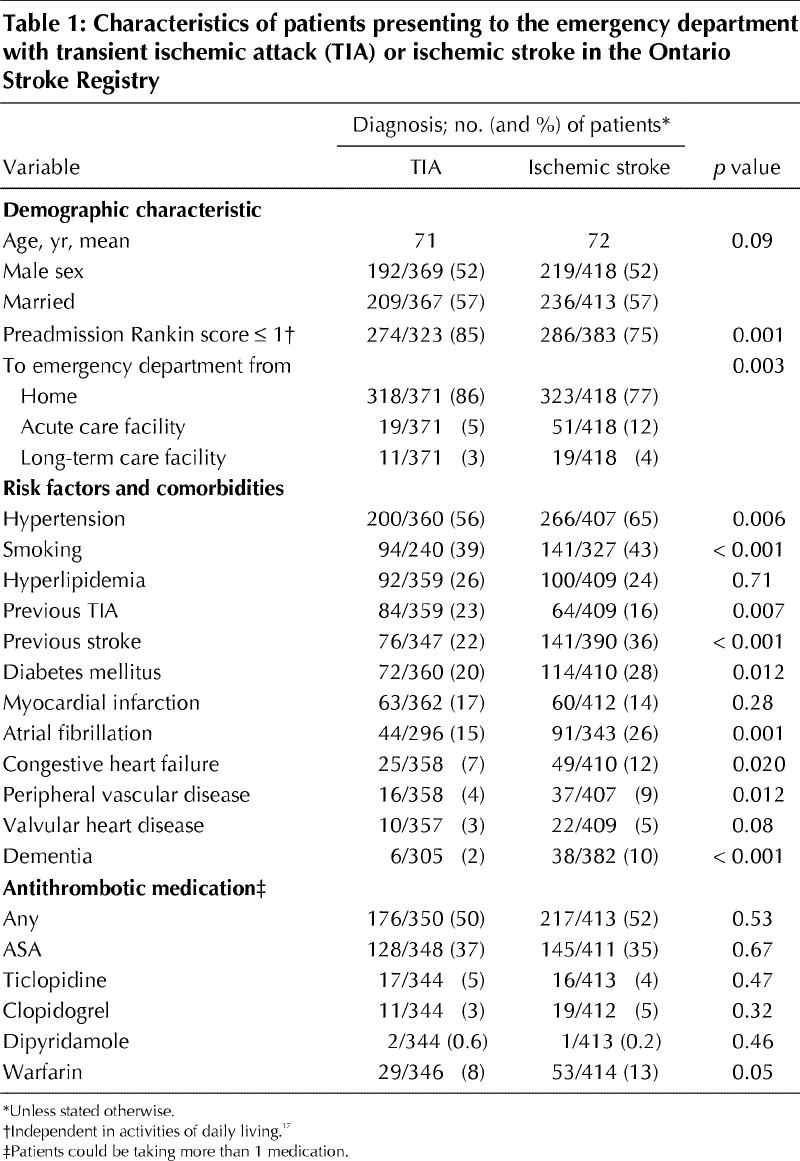

There were 371 patients with TIA and 418 with ischemic stroke diagnosed in the emergency departments of the participating institutions (Table 1). The commonest presenting TIA symptoms were hemiparesis (65%), hemisensory disturbance (45%), dysarthria (35%), aphasia (29%), facial droop (26%) and brainstem/cerebellar symptoms (20%). Median time from symptom onset to arrival at the emergency department was 120 minutes for the TIA patients.

Table 1

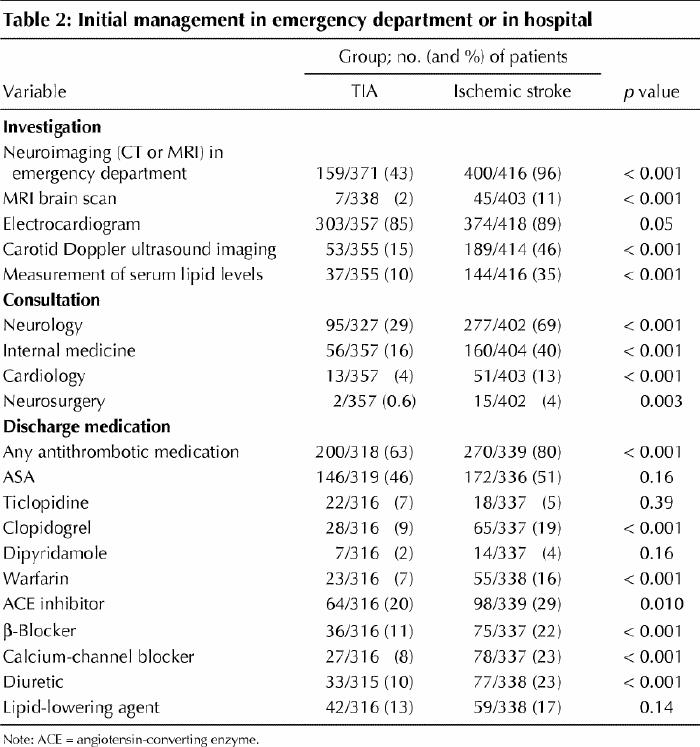

Most TIA patients were discharged from the emergency department (mean 76%, range 63%–81% across the 4 regions), as compared with only 11% of the patients with ischemic stroke. The median stay was 1 day for the TIA cohort (3 days for those admitted to hospital) versus 7 days for the stroke patients. Compared with the stroke patients, the TIA patients were less likely to receive all diagnostic investigations and specialty consultations before discharge from the emergency department or hospital and were less likely to receive prescribed secondary-prevention medications (Table 2). Over one-third of the TIA patients did not receive prescriptions for antithrombotic therapy at discharge (Table 2). For TIA patients, the likelihood of receiving a new prescription for a lipid-lowering agent was 3% and that for an antihypertensive drug (ACE inhibitor, β-blocker, calcium-channel blocker or diuretic), 8%. Neurologic consultation before discharge was obtained for 29% of the TIA patients (range 21%–41% across the 4 sites) versus 69% of the stroke patients (p < 0.001). At discharge, 58% of the TIA patients were referred to a family physician and 35% to a neurologist or stroke clinic.

Table 2

Of the 271 TIA patients discharged from the emergency department, only 31% obtained neuroimaging (CT or MRI) before discharge, 18% received neurology consultation in the emergency department, and 81% underwent electrocardiography. Antithrombotic medications were underprescribed at the time of discharge, at the following rates: ASA, 44%; ticlopidine, 8%; clopidogrel, 4%; dipryridamole, 0.4%; and warfarin, 3%.

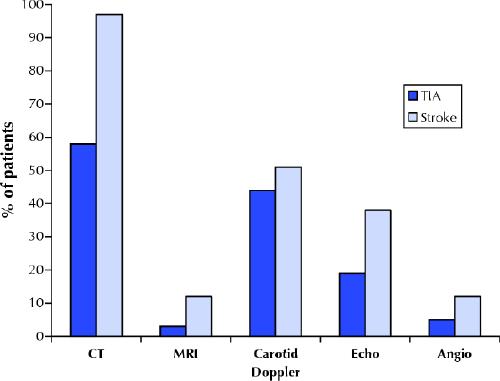

The proportions of TIA patients who underwent diagnostic investigations (inpatient or outpatient) within 30 days were as follows: CT scan, 58%; MRI, 3%; cerebral angiography, 5%; and echocardiography, 19%. These proportions were all much lower than those for the patients with stroke (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Less than half the TIA patients received carotid Doppler ultrasonography within 30 days. Among the TIA patients, carotid endarterectomy was performed in 1.7% within 30 days and 2.0% within 90 days.

Fig. 1: Proportions of patients who underwent diagnostic investigations (inpatient or outpatient) within 30 days after presenting to an emergency department with transient ischemic attack (TIA) (n = 364) or ischemic stroke (n = 410). The proportions of the TIA group were all much lower (p < 0.001) than those of the stroke group except for carotid Doppler ultrasonography (p = 0.08). Echo = echocardiography, Angio = angiography.

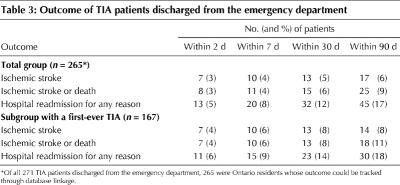

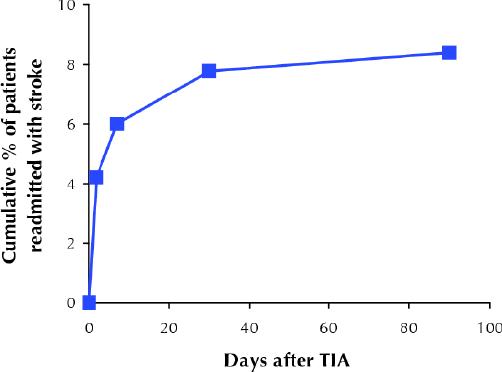

Of the 271 TIA patients discharged from the emergency department, 265 were Ontario residents who could be linked by unique identifier to the CIHI Ontario database so that outcome in terms of hospital readmission and death could be tracked (Table 3). The 30-day rates of readmission were 12% for any cause and 5% for ischemic stroke (half of the cases of stroke happened in the first 2 days). The risk of ischemic stroke or death at 30 days was 6% overall but was higher among patients whose presenting symptom involved a motor deficit (hemiparesis or facial droop; risk 12%) or speech impairment (dysarthria or aphasia; risk 9%). In the subgroup with a first-ever TIA (no prior history of TIA or stroke; n = 167), the stroke risk after discharge from the emergency department was 6% within the first week and 8% within 30 days (Table 3). Half of the patients who had a stroke within 90 days did so within the first 2 days (Fig. 2).

Table 3

Fig. 2: Early risk of stroke after discharge from the emergency department among patients with a first-ever TIA (n = 167). Note that half of the cases of stroke occurring within 3 months happened in the first 2 days after TIA.

Interpretation

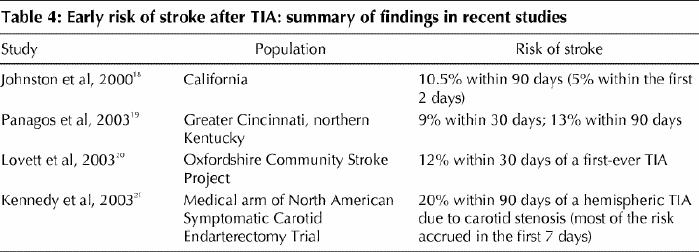

Patients with TIA diagnosed in the emergency department represent a high-risk group. We found 30-day risks of stroke after discharge from the emergency department of 5% overall, 8% among those with a first-ever TIA and 12% among those with a motor-deficit TIA. Half of the stroke cases occurring within 3 months happened in the first 2 days. Although most previous studies have focused on long-term prognosis, our data add to the growing literature on the risks very early after TIA18,19,20,21 (Table 4).

Table 4

Our findings are also consistent with recent reports of suboptimal emergency management of TIA.22,23 We found that TIA was underinvestigated and undertreated compared with stroke. Most of the TIA patients were discharged, and many of them were unlikely to receive diagnostic investigations on an outpatient basis within 30 days. Over one-third were not given prescriptions for antithrombotic therapy. Similarly, in a large US study of visits to the emergency department because of TIA, 54% of the patients were admitted, CT was performed in 56% and MRI in less than 5%, and 31% were not given prescriptions for medication.22 In Edmonton, use of carotid Doppler ultrasonography and antiplatelet therapy for TIA patients was also found to be particularly poor.23

Published guidelines1,2,3,4,5 and expert opinion7,9,24 have recommended urgent diagnostic evaluation of TIA with neuroimaging, noninvasive vascular imaging (e.g., Doppler ultrasonography, magnetic resonance angiography [MRA] or CT angiography), electrocardiography and antithrombotic therapy. Johnston7 advised that carotid imaging “be performed rapidly, ideally within 24 hours.” The goal of investigation is to identify the highest-risk causes — carotid artery disease that would benefit from revascularization25 or a cardiac source of embolism (e.g., atrial fibrillation) that would benefit from anticoagulation.26 At some centres, carotid revascularization is performed within days.27 Diffusion MRI, where available, reveals the ischemic injury in many TIA patients28 and may alter management by revealing unsuspected patterns of ischemia suggesting cardiogenic embolism. Some TIA patients may be at low risk (e.g., having brief, isolated sensory symptoms),29 and in these patients negative results of MRI and MRA suggest a favourable prognosis.30

Study limitations included a moderate sample size and potential inaccuracy in diagnostic coding of TIA by nonneurologists.31 Regardless, these data suggest that patients who are given the designation of TIA (even if inaccurate) are at risk for early hospital readmission and adverse outcomes. The risk of stroke may have been underestimated if benign conditions (e.g., migraine, syncope and seizure) were mistaken for TIA and included in our sample and because ICD-9 code 433 was not used for outcome assessment.16 We do not expect the rate of diagnostic investigations to have been underestimated in the OHIP claims database, although unmeasured factors (e.g., patient preferences, compliance and comorbidities) may account for some of the observed low rates in this study. The apparent underprescribing of antithrombotics may partially reflect undercoding if prescriptions were not documented in the chart (especially those for a nonprescription drug such as ASA) or reluctance to prescribe because of diagnostic uncertainty or medication contraindications. Antithrombotic agents may have been prescribed on an outpatient basis, but such data were not collected. When our study was conducted, the extended-release dipryridamole–ASA combination was not available in Ontario, and government reimbursement for clopidogrel required a letter of request from the physician for every patient. Although antihypertensive and lipid-lowering agents play a role in long-term stroke prevention (and many TIA patients have coronary artery disease that may also benefit from these drugs),32,33 the observed lack of prescribing of these agents is understandable until we have evidence for their use in the acute phase after TIA.

In summary, our results suggest the need for more rapid investigation and treatment decisions after a TIA in an effort to prevent an early disabling stroke or death. While it is not yet known whether immediate management will reduce the incidence of stroke, these data support the need for trials in which preventive interventions are administered early (during the highest risk period) rather than weeks or months later, as in previous studies. The Fast Assessment of Stroke and Transient ischemic attack to prevent Early Recurrence (FASTER) Trial, currently underway, is one such trial. It is designed to assess the value of early initiation (within 12 hours after TIA or minor stroke) of combination antiplatelet and lipid-lowering therapy.34 Barriers to timely TIA management include limited resource availability (e.g., of after-hours radiology services), with undue waiting times for outpatient tests. Some centres advocate short inpatient stays to facilitate rapid evaluation and observation of high-risk TIA patients,27 and the effectiveness of this approach deserves study: routine hospital admission is not cost-effective.35 It is hoped that the efforts of the Ontario Coordinated Stroke Strategy and similar initiatives in other provinces will improve care through the establishment of regional stroke prevention clinics for urgent TIA referrals, improved access to outpatient investigations, emergency department protocols and education. Physicians who do not treat TIA as a serious matter perpetuate the misconception that TIAs are somehow not as dangerous as a completed stroke because the symptoms clear quickly. The present data should prompt efforts at every institution to ensure that TIA patients are not neglected.

β See related articles pages 1105, 1113, 1123 and 1134

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the participation of the Ontario Stroke Registry's 4 demonstration sites: London Health Sciences Centre, University Campus and Victoria Campus (southwest region); Hamilton Health Sciences Centre (central west region); Trillium Health Centre and William Osler Health Centre (west Greater Toronto Area region); and Kingston General Hospital (southeast region). The registry, funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, is a collaborative effort of the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (Drs. V. Flintoft, M. Kapral, J. Tu and H. Wang), the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, the 4 demonstration sites' coordinators/project leaders (C. Bolton, K. LeBlanc, S. Nicosia and C. O'Callaghan), and the Ontario Coordinated Stroke Strategy's lead evaluator (I. Blidner) and regional evaluation research assistants (N. Absolon, K. Dziuran, D. Groll and N. Pyette).

Appendix 1.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: David Gladstone conceived of the study, designed the analyses and wrote the initial and subsequent drafts. Moira Kapral and Jack Tu, who are responsible for the design and methodology of the Ontario Stroke Registry, helped prepare and edit the manuscript. Jiming Fang performed the statistical analysis and database management. All authors contributed to the data interpretation, provided critical revisions of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. David J. Gladstone, Director, Inpatient Stroke Services, and Co-Director, Stroke Prevention Clinic, Division of Neurology and Regional Stroke Centre, Sunnybrook and Women's College Health Sciences Centre, Rm. A454, 2075 Bayview Ave., Toronto ON M4N 3M5; fax 416 480-5753; david.gladstone@sw.ca

References

- 1.Feinberg WM, Albers GW, Barnett HJ, Biller J, Caplan LR, Carter LP, et al. Guidelines for the management of transient ischemic attacks. Circulation 1994;89:2950-65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Culebras A, Kase CS, Masdeu JC, Fox AJ, Bryan RN, Grossman CB, et al. Practice guidelines for the use of imaging in transient ischemic attacks and acute stroke: a report of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke 1997;28:1480-97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Albers GW, Hart RG, Lutsep HL, Newell DW, Sacco RL. Supplement to the guidelines for the management of transient ischemic attacks: a statement from the Ad Hoc Committee on Guidelines for the Management of Transient Ischemic Attacks, Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke 1999;30:2502-11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Wolf PA, Clagett P, Easton JD, Goldstein LB, Gorelick PB, Kelly-Hayes M, et al. Preventing ischemic stroke in patients with prior stroke and transient ischemic attack: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Stroke Council of the American Heart Association. Stroke 1999;30:1991-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Brott TG, Clark WM, Fagan SC, et al. Stroke: the first hours: guidelines for acute treatment. Englewood (CO): National Stroke Association, 2000.

- 6.Holloway RG, Benesch C, Rush SR. Stroke prevention: Narrowing the evidence-practice gap. Neurology 2000;54:1899-906. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Johnston SC. Clinical practice. Transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1687-92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kelly J, Hunt BJ, Lewis RR, Rudd A. Transient ischaemic attacks: under-reported, over-diagnosed, under-treated. Age Ageing 2001;30:379-81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Albers GW, Caplan LR, Easton JD, Fayad PB, Mohr JP, Saver JL, et al, for the TIA Working Group. Transient ischemic attack — proposal for a new definition. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1713-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Goldstein LB, Bian J, Samsa GP, Bonito AJ, Lux LJ, Matchar DB. New transient ischemic attack and stroke: outpatient management by primary care physicians. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2941-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Johnston SC, Fayad PB, Gorelick PB, Hanley DF, Shwayder P, Van Husen D, et al. Prevalence and knowledge of transient ischemic attack among US adults. Neurology 2003;60:1429-34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Blidner I. Evaluation of the Coordinated Stroke Strategy: an initiative of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario: technical report. Toronto: Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario; 2001.

- 13.Stroke Registry Pilot Study: Ontario Coordinated Stroke Strategy operations manual. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2000.

- 14.Kramer MS, Feinstein AR. Clinical biostatistics: the biostatistics of concordance. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981;29:111-23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.World Health Organization manual of the International Statistical Classification of Disease, Injuries, and Causes of Death. 9th rev. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1977.

- 16.Goldstein LB. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM coding for the identification of patients with acute ischemic stroke: effect of modifier codes. Stroke 1998;29:1602-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Rankin J. Cerebral vascular accidents in patients over the age of 60. II: prognosis. Scott Med J 1957;2:200-15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, Sidney S. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA 2000;284:2901-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Panagos PD, Pancioli AM, Khoury J, Alwell K, Miller R, Kissela B, et al. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis and evaluation of transient ischemic attack (TIA). Acad Emerg Med 2003;10:432-3.

- 20.Lovett JK, Dennis MS, Sandercock PA, Bamford J, Warlow CP, Rothwell PM. Very early risk of stroke after a first transient ischemic attack. Stroke 2003;34:e138-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Kennedy J, Hill MD, Eliasziw M, Buchan AM, Barnett HJ. Short-term prognosis following acute cerebral ischaemia [abstract]. Stroke 2002;33:382.

- 22.Edlow JA, Kim S, Emond JA, Camargo CA Jr. US emergency department visits for transient ischemic attack, 1992–2000 [abstract]. Acad Emerg Med 2003;10:432. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Chang E, Holroyd BR, Kochanski P, Kelly KD, Shuaib A, Rowe BH. Adherence to practice guidelines for transient ischemic attacks in an emergency department. Can J Neurol Sci 2002;29:358-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Verro P. Stroke following TIA: mounting evidence of early risk. Stroke 2003;34:e141-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Barnett JH, Meldrum HE, Eliasziw M. The appropriate use of carotid endarterectomy. CMAJ 2002;166:1169-79. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Van Walraven C, Hart RG, Singer DE, Laupacis A, Connolly S, Petersen P, et al. Oral anticoagulants vs aspirin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: an individual patient meta-analysis. JAMA 2002;288:2441-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Moss HE, Hill MD, Demchuck AM, Barber PA, Kennedy J, Simon JE, et al. TIA reference unit: rapid investigation and management of TIA [abstract]. Stroke 2003;34:310.

- 28.Kidwell CS, Alger JR, Di Salle F, Starkman S, Villablanca P, Bentson J, et al. Diffusion MRI in patients with transient ischemic attacks. Stroke 1999;30:1174-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Johnston SC, Sidney S, Bernstein AL, Gress DR. A comparison of risk factors for recurrent TIA and stroke in patients diagnosed with TIA. Neurology 2003;60:280-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Wang DZ, Rose JA, Milbrandt JC, Rodde M, Honings D, Burhnam J, et al. Three-month outcome and cost review of TIA patients discharged from ER with normal MRI/MRA of brain [abstract]. Stroke 2003;34:318.

- 31.Ferro JM, Falcao I, Rodrigues G, Canhao P, Melo TP, Oliveira V, et al. Diagnosis of transient ischemic attack by the nonneurologist: a validation study. Stroke 1996;27:225-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Gorelick PB. Stroke prevention therapy beyond antithrombotics: unifying mechanisms in ischemic stroke pathogenesis and implications for therapy: an invited review. Stroke 2002;33:862-75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Adams RJ, Chimowitz MI, Alpert JS, Awad IA, Cerqueria MD, Fayad P, et al; Stroke Council and the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Coronary risk evaluation in patients with transient ischemic attack and ischemic stroke: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the Stroke Council and the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Circulation 2003;108:1278-90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Kennedy J, Eliasziw M, Hill MD, Buchan AM. The Fast Assessment of Stroke and Transient ischemic attack to prevent Early Recurrence (FASTER) Trial. Sem Cerebrovasc Dis 2003;3:25-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Gubitz G, Phillips S, Dwyer V. What is the cost of admitting patients with transient ischemic attacks to hospital? Cerebrovasc Dis 1999;9:210-4. [DOI] [PubMed]