Abstract

TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK (TIA) provides a golden opportunity for stroke prevention. TIA should be treated as a medical emergency with prompt investigations to determine the mechanism of ischemia and subsequent preventive therapy. The risk of stroke after TIA is estimated to be 10%–20% in the first 90 days. The risk is time-dependent with 50% of the risk accruing in the first 48 hours. In this review, we describe the diagnosis and management of TIA, introduce new concepts in TIA and suggest that all patients with significant TIA should undergo rapid investigation and management to prevent stroke.

Case

Mr. P, a 76-year-old man, presents to the emergency department after experiencing the sudden onset of slurred speech associated with tingling and clumsiness of his right hand. The symptoms lasted about 30 minutes and have completely resolved. His examination is now unremarkable. He has a history of hypertension (controlled on medication) and dyslipidemia. What is the appropriate management of this patient?

A transient ischemic attack (TIA) is a syndrome characterized by the sudden onset of discrete neurological symptoms that resolve completely within 24 hours. TIA frequently precedes ischemic stroke, particularly in the territory of the carotid arteries. In developed countries, TIA may be reported by 0.5%–8% of the elderly population.1 Precise estimates of the incidence of TIA in the community are lacking, in part because patients may be unaware of the importance of classic symptoms of cerebral ischemia and thus fail to seek medical attention.2 Furthermore, physician knowledge and management of TIA in the community is variable.3 Recently, the options for the effective secondary prevention of stroke have begun to expand with the publication of important data on the medical and surgical management of cerebrovascular disease.

A patient presenting with a TIA is at high risk of subsequent adverse events. The 90-day risk of stroke has been reported to be greater than 10%, with the highest risk occurring in the first 2 days.4 When recurrent TIAs, myocardial infarction and death from any cause are considered, the risk is more than 25% over the first 3 months. Early recognition of TIA and subsequent timely intervention is of obvious importance.

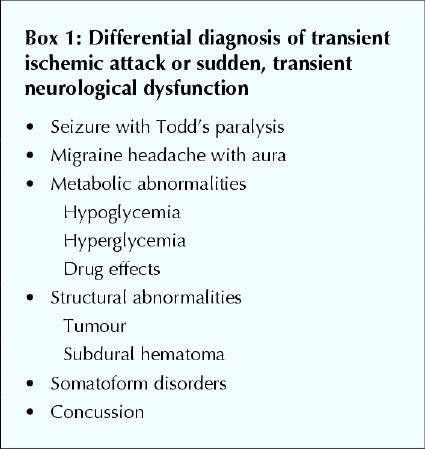

The differential diagnosis of transient focal neurological symptoms is wide and includes vascular, metabolic and structural disorders (Box 1).

Box 1.

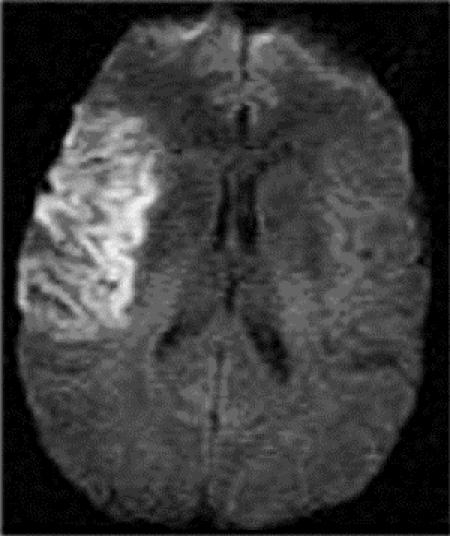

The vast majority of TIAs are brief, with symptoms lasting less than an hour.5,6,7 Recent studies of TIAs using highly sensitive neuroimaging techniques have shown that patients with complete resolution of symptoms may still have evidence of continuing tissue damage (Fig. 1), thus challenging the older, arbitrary definition of 24 hours of symptom duration.8 Despite recent advances, however, the diagnosis of TIA remains a “clinical” one.

Fig. 1: Diffusion-weighted MRI showing an acute large stroke in the right middle cerebral artery territory. This patient had had a right-hemisphere transient ischemic attack (TIA) several days before admission but had not sought medical attention. Unfortunately, he presented to the hospital late and was not eligible for treatment with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA).

A thorough and prompt history-taking and physical examination are important for all patients presenting with transient neurological symptoms to confirm the diagnosis of the cerebral ischemic syndrome. Localization of the symptoms and signs remains an important part of the clinical examination. The localization reveals the vascular territory affected and helps to direct investigations. TIA affecting the carotid artery territory typically results in contralateral motor, sensory and higher cortical symptoms. Left carotid territory ischemia commonly results in a language disorder or aphasia. A posterior aphasia (Wernicke's type aphasia) is commonly misdiagnosed as “confusion” or “delirium” because, unlike anterior aphasia (Broca's type aphasia), the patient remains fluent but cannot comprehend the spoken or written word and produces nonsensical speech. Ischemia in the right carotid territory can result in hemispatial neglect, which may be misinterpreted as “vagueness” or “malaise” or the patient “not being herself.” Amaurosis fugax is brief (often lasting less than 5 minutes), monocular and consists of “negative” symptoms such as greying of colours, blurring, fogging or complete loss of vision. Amaurosis is strongly associated with internal carotid artery stenosis, because the ophthalmic artery is the first branch of the internal carotid artery. Hemianopia may occur with both anterior or posterior circulation ischemia, and many patients will interpret it as loss of vision in one eye rather than in half of the visual field of both eyes. Unless the patient covers his or her eyes alternately, it may not be possible to distinguish hemianopia from amaurosis fugax on historical grounds alone. TIA affecting the posterior circulation may result in a myriad of possible symptoms, including vertigo, imbalance, ataxia and cranial nerve dysfunction. With the exception of amaurosis fugax, posterior ischemia may mimic all of the anterior circulation syndromes.

Because the clinical features of TIA have usually resolved by the time the patient seeks medical attention, the findings on neurological examination are often normal. Therefore, timely investigations are directed toward confirming the mechanism of the TIA and for planning interventions aimed at preventing subsequent stroke. The decision to evaluate a patient should be based on the presumption that the information acquired will contribute to management decisions or will lead to an etiologic diagnosis. The common causes of cerebrovascular ischemia include atherothrombotic disease of the intra- or extracranial circulation and cardiac emboli secondary to dysrhythmia or structural abnormalities (e.g., valvular disorders). A significant minority of patients have an uncertain mechanism despite extensive investigation.9,10

Crescendo TIA is a term commonly used to describe multiple recurrent episodes of TIA over hours to days. The term is not particularly useful because it does not define a group of patients with a particular mechanism of TIA, such as carotid stenosis; the cause may as likely be small-vessel disease, cardiac embolus, seizure or somatization. Management of “crescendo” TIA is no different than that of single or multiple TIAs.

Prompt clinical evaluation is important in patients with recent symptoms in order to ensure that the symptoms have truly resolved. Patients presenting within 3 hours after the onset of ischemic stroke symptoms may have fluctuating symptoms as a manifestation of intracranial vessel occlusion and marginal blood flow through collateral circulation. Such patients with disabling symptoms may be considered for thrombolytic therapy in centres capable of administering this treatment.11,12

Initial investigations

A complete blood count and determination of the prothrombin time, international normalized ratio, fasting blood sugar level and serum cholesterol level are required. A 12-lead electrocardiogram is important for detecting atrial fibrillation as well as concurrent cardiovascular disease.13 More extensive blood tests, including those for hypercoagulability, homocysteine levels and rheumatologic conditions, are rarely useful during the initial work-up.

Imaging studies

Brain imaging

All patients with TIA should undergo neurological imaging (CT or MRI) on the same day as their presentation. Although nonvascular lesions account for less than 1% of patients presenting with TIA,13 CT scanning should be included in the workup of patients presenting with TIA, primarily to rule out structural causes, such as intracerebral hemorrhage, tumour and subdural hematoma.14 The role of MRI in the evaluation of TIA has yet to be defined. Although there is ongoing investigation into the performance characteristics of MRI in detecting TIA's, it is felt that the higher resolution afforded by MRI compared with that of CT scanning results in a greater sensitivity for the detection of early ischemia, especially in the posterior fossa.

Neurovascular imaging

Evaluation of the extracranial circulation is an important component of the diagnostic workup. For the anterior circulation, carotid ultrasonography is the most common imaging method used.15,16,17 The presence or absence of a neck bruit on clinical examination should not alter the decision to image the carotid bifurcation, since this finding is neither sensitive nor specific. The discovery of severe carotid stenosis (> 70%) in patients who present with a TIA is an important finding because there is good evidence that endarterectomy is superior to medical management in this group of patients.15,17 Patients with anterior circulation ischemia should have their carotid arteries imaged within 24 hours after their TIA so that prompt surgical management can ensue.

Although ultrasonography is not generally appropriate on its own for surgical decision-making, it is a reasonable screening tool.18 Carotid ultrasonography is associated with an important error rate that may approach 25% when used alone to select patients for carotid endarterectomy.18 A second noninvasive test (CT angiography or MR angiography) should be used to confirm the ultrasound findings in patients with estimated stenosis of more than 70% before proceeding to surgery. Both CT and MR angiography are very accurate in identifying vascular lesions (Fig. 2). Imaging of the posterior circulation is best accomplished noninvasively with MR angiography. However, CT angiography is less expensive and more widely available. Both forms of imaging depend on user technique and local expertise. Ideally, patients should receive imaging of the brain parenchyma and vasculature in the same session.

Fig. 2: Left: Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiogram of the right carotid artery showing a tight stenosis (> 70%) of the right internal carotid artery just distal to the bifurcation. Right: Formal selective cerebral angiogram showing the same lesion. The patient had had a TIA and was enrolled in a clinical trial in which he received carotid angioplasty and stenting to treat his symptomatic carotid stenosis.

Catheter angiography has become the putative “gold standard” for evaluating the carotid arteries before surgery, because it was used in the major trials that demonstrated the benefit of carotid endarterectomy a decade or more ago. Although complications associated with catheter angiography are uncommon, this test should be reserved for patients being considered for surgery or in whom diagnostic uncertainty remains after noninvasive imaging.19 Evaluation of the intracranial cerebral circulation may be important in selected patients, but in general it is unlikely to alter management decisions for the patient presenting with TIA.

Future directions

Recent evidence suggests that the risk of stroke after TIA is heavily time-dependent. Half of the 90-day risk accrues in the first 48 hours after TIA.4,20 As yet, there are no known proven effective treatments to reduce this 90-day risk. Treatment strategies are based on reasonable extrapolation of data from trials of secondary stroke prevention.

Published clinical trials of antiplatelet agents, cholesterol-lowering agents or antihypertensive agents have generally grouped all stroke types and TIA mechanisms together. However, some TIAs may be caused by microhemorrhages rather than ischemia, which implies a significant risk of intracerebral hemorrhage rather than ischemic stroke.21,22 Other TIAs may be caused by embolism from an aortic arch plaque. It is logical to believe that both acute and preventive treatments can and should be tailored to the underlying mechanism implicated. Current technology using ultrasonography and CT and MR imaging permits rapid acquisition of neurovascular information to determine the mechanism. Focused trials or trials large enough to analyze subgroups by TIA mechanism are now needed to address the role of various therapies by particular stroke type and mechanism. A study is underway to investigate the role of hyperacute preventive therapy for TIA, including medical and surgical or endovascular treatments.

Finally, imaging may further alter the landscape by changing the definition of both TIA and minor stroke. MRIs of patients with TIA have shown that new areas of restricted diffusion are present in nearly half of the patients, particularly if their symptoms lasted more than 1 hour, which demonstrates that permanent ischemia may result in transient symptoms.8 New definitions of TIA and stroke have been proposed whereby a TIA is defined as “a brief episode of neurologic dysfunction caused by focal brain or retinal ischemia, with clinical symptoms typically lasting less than one hour, and without evidence of acute infarction.” The corollary is that persistent clinical signs or characteristic imaging abnormalities define infarction — that is, stroke.23

Summary

TIA is a medical emergency and provides an important opportunity for the clinician to intervene and prevent the occurrence of stroke, a devastating, life-altering outcome for many patients. Effective interventions exist for secondary stroke prevention. However, early recognition of TIA by patients and their physicians remains the most important step in the effective prevention of disability from stroke. Therefore, all patients with a hemispheric TIA — presenting with motor deficit, speech deficit, hemianopia or hemispatial neglect — require urgent investigations. Patients with isolated sensory syndromes or dizziness, without weakness or cortical signs, empirically have a benign course24 and can complete their workup as an outpatient.

The case revisited

Mr. P is found to have normal sinus rhythm, normal results of routine blood tests and a normal CT scan. However, carotid duplex ultrasonography demonstrates a stenosis of 85% of the left carotid artery. Subsequent CT angiography confirms the degree of narrowing. The patient begins ASA therapy and undergoes an uncomplicated endarterectomy 2 days later. At follow-up 1 month later, he is found to be hypertensive despite the use of a diuretic, and both his total cholesterol and LDL levels are high. An angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor and statin drug are added to his medications. Mr. P is well at follow-up 12 months later.

β See related articles pages 1099, 1105, 1113 and 1123

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Both authors contributed equally to the research and writing of the article and approved the final version.

Competing interests: None declared for Dean Johnston. Michael Hill has received speaker fees or honoraria, or both, from Sanofi Synthelabo Canada Inc. and Boehringer Ingelheim (Canada) Ltd.

Correspondence to: Dr. Dean C.C. Johnston, Clinical Assistant Professor, Centre for Health Evaluation and Outcome Sciences, Rm. 2369, Providence Wing, St. Paul's Hospital, 1081 Burrard St., Vancouver BC V6Z 1Y6; fax 604 806-8624; dccj@interchange.ubc.ca

References

- 1.Bots ML, van der Wilk EC, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Grobbee DE. Transient neurological attacks in the general population: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical relevance. Stroke 1997;28(4):768-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Johnston SC, Fayad PB, Gorelick PB, Hanley DF, Shwayder P, van Husen D, et al. Prevalence and knowledge of transient ischemic attack among US adults. Neurology 2003;60(9):1429-34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Goldstein LB, Bian J, Samsa GP, Bonito AJ, Lux LJ, Matchar DB. New transient ischemic attack and stroke: outpatient management by primary care physicians. Arch Intern Med 2000;160(19):2941-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, Sidney S. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA 2000;284(22):2901-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dyken ML, Conneally M, Haerer AF, Gotshall RA, Calanchini PR, Poskanzer DC, et al. Cooperative study of hospital frequency and character of transient ischemic attacks. I. Background, organization, and clinical survey. JAMA 1977;237(9):882-6. [PubMed]

- 6.Levy D. How transient are transient ischemic attacks? Neurology 1988;38 (5): 674-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Werdelin L, Juhler M. The course of transient ischemic attacks. Neurology 1988;38(5):677-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kidwell CS, Alger JR, Di Salle F, Starkman S, Villablanca P, Bentson J, et al. Diffusion MRI in patients with transient ischemic attacks. Stroke 1999;30 (6): 1174-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Madden KP, Karanjia PN, Adams HP Jr, Clarke WR. Accuracy of initial stroke subtype diagnosis in the TOAST study. Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Neurology 1995;45(11):1975-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Sacco RL. Risk factors and outcomes for ischemic stroke. Neurology 1995;45(2 Suppl 1):S10-4. [PubMed]

- 11.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 1995; 333(24):1581-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Adams HP, Jr., Brott TG, Furlan AJ, Gomez CR, Grotta J, Helgason CM, et al. Guidelines for Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Stroke: a Supplement to the Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke. A statement for healthcare professionals from a Special Writing Group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke 1996;27(9):1711-8. [PubMed]

- 13.Hankey GJ, Warlow CP. Cost-effective investigation of patients with suspected transient ischaemic attacks. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992;55(3):171-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Guidelines for the management of transient ischemic attacks. From the Ad Hoc Committee on Guidelines for the Management of Transient Ischemic Attacks of the Stroke Council of the American Heart Association. Stroke 1994; 25 (6):1320-35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med 1991;325(7):445-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.European Carotid Surgery Trial Collaborators. Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST). Lancet 1998;351(9113):1379-87. [PubMed]

- 17.Barnett HJ, Taylor DW, Eliasziw M, Fox AJ, Ferguson GG, Haynes RB, et al. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med 1998;339(20):1415-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Johnston DCC, Goldstein LB. Clinical carotid endarterectomy decision making: Noninvasive vascular imaging versus angiography. Neurology 2001;56(8): 1009-15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Johnston DCC, Chapman KM, Goldstein LB. Low rate of complications of cerebral angiography in routine clinical practice. Neurology 2001;57:2012-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Coull AJ, Lovett JK, Rothwell PM. Population based study of early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke: implications for public education and organisation of services. BMJ 2004;328(7435):326. Epub 2004 Jan 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Kidwell CS, Saver JL, Villablanca JP, Duckwiler G, Fredieu A, Gough K, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging detection of microbleeds before thrombolysis: an emerging application. Stroke 2002;33(1):95-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Nighoghossian N, Hermier M, Adeleine P, Blanc-Lasserre K, Derex L, Honnorat J, et al. Old microbleeds are a potential risk factor for cerebral bleeding after ischemic stroke: a gradient-echo T2*-weighted brain MRI study. Stroke 2002; 33(3):735-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Albers GW, Caplan LR, Easton JD, Fayad PB, Mohr JP, Saver JL, et al. TIA Working Group. Transient ischemic attack — proposal for a new definition. N Engl J Med 2002;347(21):1713-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Claiborne Johnston S, Sidney S, Bernstein AL, Gress DR. A comparison of risk factors for recurrent TIA and stroke in patients diagnosed with TIA. Neurology 2003;60:280-5. [DOI] [PubMed]