Abstract

Spindle assembly is subject to the regulatory controls of both the cell-cycle machinery and the Ran-signaling pathway. An important question is how the two regulatory pathways communicate with each other to achieve coordinated regulation in mitosis. We show here that Cdc2 kinase phosphorylates the serines located in or near the nuclear localization signal (NLS) of human RCC1, the nucleotide exchange factor for Ran. This phosphorylation is necessary for RCC1 to generate RanGTP on mitotic chromosomes in mammalian cells, which in turn is required for spindle assembly and chromosome segregation. Moreover, phosphorylation of the NLS of RCC1 is required to prevent the binding of importin α and β to RCC1, thereby allowing RCC1 to couple RanGTP production to chromosome binding. These findings reveal that the cell-cycle machinery directly regulates the Ran-signaling pathway by placing a high RanGTP concentration on the mitotic chromosome in mammalian cells.

Keywords: Ran, RCC1, spindle, mitosis, chromosome, FRET

The small GTPase Ran represents a unique signal transduction system in eukaryotic cells that regulates diverse cellular functions through a family of nuclear import and export receptors. The mechanism by which Ran regulates nucleocytoplasmic trafficking is well established (Mattaj and Englmeier 1998; Weis 2002). A protein destined for nuclear import or export contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS) or nuclear export signal (NES), which is recognized by import or export receptors, respectively. Nuclear import and export are regulated by the asymmetric distribution of Ran regulatory proteins. Unlike many other small GTPases, Ran has only one known nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), RCC1, and one known GTPase activating enzyme, RanGAP1 (Cole and Hammell 1998; Moore 2001). Mammalian RCC1 contains an NLS at its N terminus and is imported into the nucleus, where it interacts with chromatin via core histones H2A and H2B, whereas RanGAP1 is localized in the cytoplasm (Nemergut and Macara 2000; Talcott and Moore 2000; Nemergut et al. 2001; Bilbao-Cortes et al. 2002). This distribution of regulatory proteins establishes a high RanGTP concentration in the nucleus that is essential to drive nucleocytoplasmic transport (Mattaj and Englmeier 1998; Weis 2002).

Besides its well established role in nucleocytoplasmic trafficking, Ran also functions in spindle assembly (Carazo-Salas et al. 1999; Kalab et al. 1999; Wilde and Zheng 1999), nuclear envelope formation (Hetzer et al. 2000; Zhang and Clarke 2000), and spindle check point (Arnaoutov and Dasso 2003). Interestingly, Ran uses a similar mechanism to regulate spindle assembly in mitosis and nuclear import in interphase (Gruss et al. 2001; Nachury et al. 2001; Wiese et al. 2001). In animal cells, spindle assembly factors such as TPX2 and NuMA contain NLSs and are imported into the nucleus in interphase. In mitosis, a breakdown of nuclear envelope results in mixing of the nuclear compartment with the cytoplasm, thereby permitting the binding of nuclear import receptors to their cargos in the mitotic cytosol. Several studies have shown that importin α and β bind to TPX2 and NuMA in mitosis, and that RanGTP can prevent this binding. Because importin α and β are potent inhibitors of spindle assembly in mitosis, it has been hypothesized that the binding of importin α and β to the NLS-containing spindle assembly factors inhibits spindle assembly. Therefore, RanGTP is required to stimulate spindle assembly by releasing spindle assembly factors from importin α and β in the same manner as in nuclear import (Gruss et al. 2001; Nachury et al. 2001; Wiese et al. 2001).

We recently showed that RanGTP activates the essential mitotic kinase Aurora A through TPX2 in a microtubule-dependent manner. The binding of importin α and β to TPX2 not only inhibits the interaction between Aurora A and TPX2, but also blocks Aurora A activation (Tsai et al. 2003). Interestingly, the binding of importin α and β to the NLS of TPX2 also inhibits the ability of TPX2 to nucleate microtubules (Schatz et al. 2003). RanGTP is required to release importin α and β from TPX2, thus stimulating Aurora A activation, bipolar spindle assembly (Tsai et al. 2003), and microtubule nucleation (Schatz et al. 2003).

Because spindle assembly occurs toward condensed chromosomes, a high RanGTP concentration on the condensed chromosome generated by the chromatin-associated RCC1 has been hypothesized to be essential for spindle assembly. Consistent with this idea, enriched RanGTP has been detected on mitotic chromosomes assembled in cytostatic factor (CSF)-arrested Xenopus egg extracts (Kalab et al. 2002). Furthermore, we have shown that RCC1 is a highly mobile enzyme that couples its catalytic activity to chromosome binding through the binary complex of RCC1–Ran in vivo. Our computer simulations suggested that the chromosome-coupled exchange mechanism can sustain the production of a high RanGTP concentration on mitotic chromosomes (Li et al. 2003). However, recent mathematical modeling has questioned the existence of a high RanGTP concentration in tissue culture cells (Gorlich et al. 2003). Although the role of RanGTP in spindle assembly has been established in Xenopus egg extracts, whether a high RanGTP concentration exists on mitotic chromosomes and whether this RanGTP is required for spindle assembly in mammalian cells have not been established.

The discovery of the Ran-signaling pathway in regulating spindle assembly also raises another important question regarding whether and how the Ran system is coordinated with the cell-cycle machinery in mitosis. Although cross-talk between the cell-cycle machinery and the Ran system has been implicated by several studies (Kornbluth et al. 1994; Ren et al. 1995; Guarguaglini et al. 2000), the mechanism of communication has remained obscure. Here we report that RCC1 is phosphorylated in mitosis by Cdc2 kinase. This phosphorylation is essential for positioning a high RanGTP concentration on mitotic chromosomes and for spindle assembly in mammalian cells.

Results

Human RCC1 is phosphorylated on Ser 2 and Ser 11 in mitosis by Cdc2 kinase

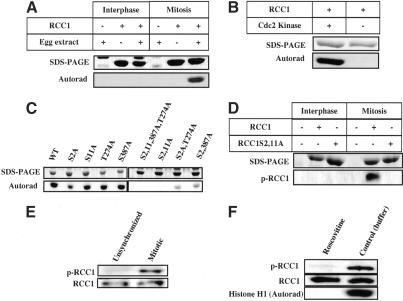

We found that purified, bacterially expressed human 6His-RCC1 was phosphorylated in mitotic but not in interphase Xenopus egg extracts (Fig. 1A). Inspection of the human RCC1 sequence revealed four threonine (T)/serine (S)-proline (P) sites that could be phosphorylated by proline-directed kinases such as Cdc2. Importantly, the first two putative phosphorylation sites, 1-MSPKR-5 and 10-RSPPA-14, agree well with the consensus sequence for Cdc2 phosphorylation. The latter of the two consensus sites is conserved in all known mammalian RCC1. Furthermore, we found that purified human 6His-RCC1 was an excellent substrate for Cdc2 kinase in vitro (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

RCC1 phosphorylation. (A) RCC1 is phosphorylated in mitosis. Purified human 6His-RCC1 or control buffer was incubated in interphase or mitotic egg extracts in the presence of γ-32p-ATP. RCC1 phosphorylation was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Cdc2 kinase phosphorylates 6His-RCC1. Purified 6His-RCC1 was incubated with Cdc2 kinase or control buffer in the presence of γ-32p-ATP, followed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (C) S2 and S11 of RCC1 were phosphorylated in mitosis. Purified wild-type or mutant 6His-RCC1 was incubated in mitotic egg extracts in the presence of γ-32p-ATP and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (D) Phosphospecific RCC1 antibody recognizes RCC1 treated with the mitotic, but not the interphase, egg extracts. (E) RCC1 is phosphorylated on S2 and/or S11 in mitotic HeLa cells. RCC1 isolated from unsynchronized or mitotic-arrested HeLa cells was probed with phosphospecific antibody (p-RCC1) or antibody recognizing both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated RCC1 (RCC1). (F) RCC1 is phosphorylated by Cdc2 kinase in HeLa cells. RCC1 isolated from mitotic-arrested HeLa cells treated with roscovitine or control buffer was probed with antibodies against RCC1 as in E. Cdc2 kinase activity in cell lysates was assayed using histone H1 as a substrate.

To further characterize RCC1 phosphorylation, we mutated the S or T in the four sites into alanines (A) either individually or in combinations. Changing any one of the S or T to A did not block RCC1 phosphorylation in mitotic egg extracts (Fig. 1C). However, when both S2 and S11 were simultaneously mutated to As, the resulting 6His-RCC1S2,11A failed to be phosphorylated, whereas all of the other double mutants were phosphorylated (Fig. 1C). As expected, mutating all four sites to As (the 6His-RCC1S2,11,387A-T274A) also blocked phosphorylation (Fig. 1C). In addition, we found that purified RCC1S2A and RCC1S11A, but not RCC1S2,11A, could be phosphorylated by Cdc2 kinase in vitro (data not shown). This suggests that RCC1 is phosphorylated on S2 and S11 by Cdc2 kinase in mitosis.

To determine whether RCC1 is phosphorylated in mitosis in vivo, we generated a phosphopeptide antibody against the first 13 amino acids of human RCC1 that were phosphorylated on S2 and S11 (MpSPKRIAKRRpSPP). This antibody recognized only the human RCC1 that was treated by mitotic Xenopus egg extracts (Fig. 1D), confirming the specificity of the antibody for phosphorylated RCC1. Next, we isolated RCC1 from cell lysates made from unsynchronized or mitotic-arrested HeLa cells using purified 6His-RanT24N, a mutant Ran that binds to RCC1 tightly (Dasso et al. 1994; Kornbluth et al. 1994; Klebe et al. 1995; Lounsbury et al. 1996). We found that the phosphospecific antibody strongly recognized only RCC1 from the mitotic cell lysate (Fig. 1E).

Finally, we asked whether Cdc2 kinase was responsible for RCC1 phosphorylation in HeLa cells. The cells were first arrested in mitosis using nocodazole and then treated with either the Cdc2 inhibitor roscovitine or buffer control. We found that RCC1 was phosphorylated in the buffer-treated cells but not in the roscovitine-treated cells (Fig. 1F). A histone H1 phosphorylation assay further confirmed that Cdc2 kinase activity was inhibited by roscovitine but not by buffer control (Fig. 1F). Furthermore, our analyses showed that RCC1 was quantitatively phosphorylated in mitotic HeLa cells (Supplementary Fig. S1). Thus, RCC1 is phosphorylated on S2/S11 by Cdc2 kinase in HeLa cells.

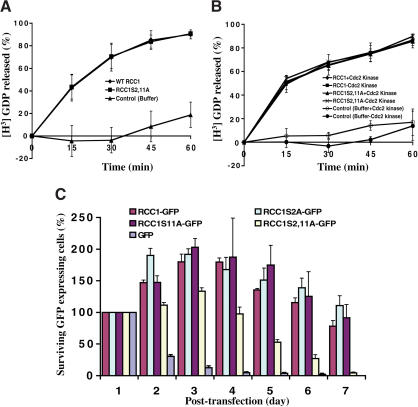

RCC1S2,11A exhibits a similar GEFactivity as wild-type RCC1 in vitro

To understand the effect of mitotic phosphorylation of RCC1, we first asked whether mutating S2/S11 to A2/A11 could affect the GEF activity of RCC1 in vitro. Bacterially expressed and purified 6His-RCC1S2,11A has the same GEF activity as wild-type RCC1 in vitro (Fig. 2A). Next, we asked whether phosphorylation of wild-type RCC1 could enhance its GEF activity in vitro. Purified wild-type or mutant RCC1 was treated with Cdc2 kinase and then used in GEF assays. Both forms of RCC1 exhibited similar GEF activities (Fig. 2B). Consistent with these results, competition assays demonstrated that both RCC1 and RCC1S2,11A exhibited similar binding affinities toward either wild-type or mutant Ran (Supplementary Fig. S2). Thus, mutating S2/S11 to A2/ A11 does not change the GEF activity of RCC1 or the affinity of RCC1 toward Ran.

Figure 2.

Mitotic phosphorylation of RCC1 is essential in vivo. (A) RCC1 and RCC1S2,11A have the same GEF activity in vitro. (B) Phosphorylation of RCC1 does not affect its GEF activity in vitro. Purified 6His-RCC1 or 6His-RCC1S2,11A was phosphorylated by Cdc2 kinase and then used in GEF assays. (C) Phosphorylation of S2 or S11 is essential for RCC1 function in vivo. RCC1-GFP, RCC1S2A-GFP, RCC1S11A-GFP, RCC1S2,11A-GFP, or GFP vector was used to transfect tsBN2 cells. One day posttransfection, the cells were shifted to 39.5°C to inactivate endogenous RCC1. The surviving GFP-expressing cells were determined as a percentage of the initial GFP-expressing cells at day 1.

Phosphorylation of RCC1 is essential for its function in vivo

To determine whether phosphorylation of RCC1 in mitosis is essential in vivo, we used the Chinese hamster cell line tsBN2 that harbors a temperature-sensitive mutation in RCC1. When tsBN2 cells are shifted to the restrictive temperature (39.5°C), endogenous RCC1 is largely degraded in 2–3 h, which causes cell death (Nishitani et al. 1991). We have shown that the wild-type human RCC1 fused to GFP at its C terminus (RCC1-GFP) supports the growth of tsBN2 cells at the restrictive temperature (Li et al. 2003). To determine whether phosphorylation of RCC1 is essential in vivo, we transfected tsBN2 cells with RCC1-GFP, RCC1S2A-GFP, RCC1S11A-GFP, or RCC1S2,11A-GFP and shifted the cells to 39.5°C 1 d after transfection. We found that mutating either S2 or S11 to A did not affect the ability of RCC1 to rescue tsBN2 cells (Fig. 2C). We were able to isolate stable cell lines expressing RCC1-GFP, RCC1S2A-GFP, and RCC1S11A that could grow at 39.5°C (data not shown). However, when both S2 and S11 were mutated, the resulting RCC1S2,11A-GFP failed to rescue the tsBN2 cells (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, RCC1S2,11D-GFP (replacing S2/11 with aspartic acid “D”), which mimics the phosphorylated form of RCC1, is able to rescue tsBN2 cells at 39.5°C (Supplementary Fig. S3A). This demonstrates that phosphorylation of RCC1 on either S2 or S11 in mitosis is essential for its function in vivo.

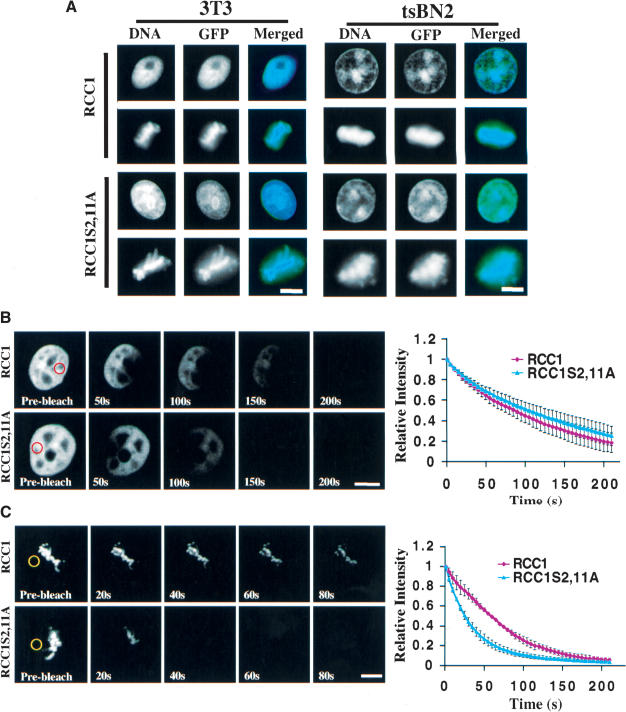

Phosphorylation of RCC1 regulates its interaction with mitotic chromosomes in vivo

To further understand the role of RCC1 phosphorylation, we asked whether RCC1S2,11A-GFP is localized properly in vivo. Both RCC1-GFP and RCC1S2,11A-GFP colocalized with DAPI in interphase nuclei and on mitotic chromosomes in Swiss 3T3 and tsBN2 cells (Fig. 3A). Therefore, the nonphosphorylatable RCC1 does not have apparent defects in nuclear import in interphase or chromosome localization in mitosis.

Figure 3.

Phosphorylation of RCC1 regulates its interaction with mitotic chromosomes. (A) Nonphosphorylatable RCC1 is properly localized. Swiss 3T3 and tsBN2 cells expressing wild-type RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP were localized by fixation and fluorescence microscopy. FLIP of RCC1 in interphase (B) and mitosis (C). A spot marked by red or yellow circles in interphase nuclei or mitotic cytosol, respectively, was repeatedly photobleached in 3T3 cells expressing RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP. Representative FLIP images are shown. Fluorescence intensity of the RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP was quantified after each bleach pulse and plotted as relative intensity versus time. Error bars show S.D. of three to five independent experiments from different cells. Bars, 10μm.

However, the proper localization of RCC1S2,11A-GFP observed above does not exclude the possibility that the mutant RCC1 might have altered binding affinity to chromatin. Previously, we used fluorescence loss after photobleaching (FLIP) to show that RCC1 continuously binds to and dissociates from chromatin in interphase and mitosis (Li et al. 2003). A change in the chromosome-binding affinity of RCC1 could disrupt RanGTP production on mitotic chromosomes, resulting in mitotic defects. Therefore, we used FLIP to examine whether RCC1S2,11A-GFP has altered chromatin-binding characteristics compared to RCC1-GFP in vivo. One spot in the mitotic cytosol or interphase nuclei expressing RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP was repeatedly photobleached. The overall fluorescence loss on mitotic chromosomes and in interphase nuclei was measured over time, which revealed the dissociation kinetics of RCC1 from chromosomes. As expected, mutant and wild-type RCC1-GFP exhibited similar FLIP kinetics in interphase nuclei in 3T3 cells (Fig. 3B). However, in mitosis, FLIP of RCC1S2,11A-GFP was significantly faster than that of RCC1-GFP (Fig. 3C), indicating that the nonphosphorylatable RCC1 has a reduced binding capacity to mitotic chromosomes. Similar results were obtained in tsBN2 cells (data not shown). Thus, phosphorylation specifically regulates the interaction between RCC1 and chromosomes in mitosis.

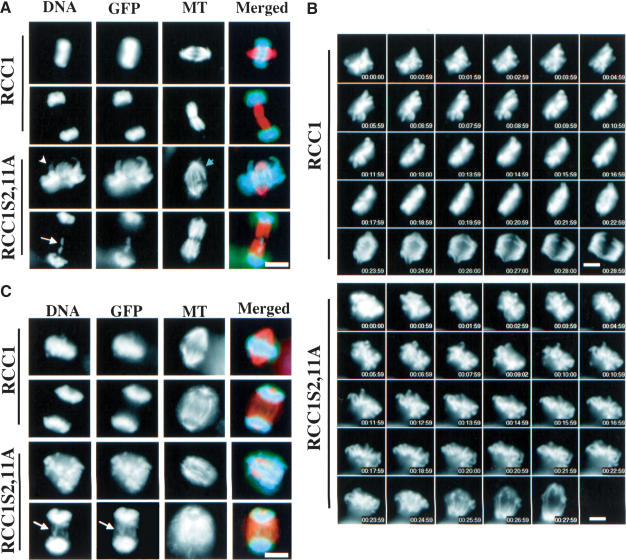

Phosphorylation of RCC1 is required for spindle assembly and chromosome segregation

Because RCC1S2,11A binds to Ran and chromosomes, it could interfere with wild-type RCC1 function when overexpressed, thereby causing a dominant negative effect. To test this, we transiently overexpressed (more than fivefold of the endogenous RCC1) RCC1S2,11A-GFP or RCC1-GFP in Swiss 3T3 and tsBN2 cells, and we found that a significant fraction of cells expressing RCC1S2,11A-GFP had mitotic defects compared to cells expressing RCC1-GFP. Quantification of these defects, which include abnormal metaphase spindle, lack of metaphase chromosome alignment/arm congression, and lagging chromosomes in anaphase, are summarized in Table 1. Examples of these defects are shown in Figure 4A. It is interesting to note that cells overexpressing RCC1S2,11A-GFP often exhibit a lack of chromosome arm congression to the metaphase plate despite the presence of a metaphase spindle (Fig. 4A, white arrowhead and blue arrow), suggesting that chromosome arm congression might be regulated by RanGTP. Time-lapse fluorescence microscopy further revealed that in cells expressing RCC1-GFP, the condensed chromosomes congressed tightly at the metaphase plate before anaphase onset (Fig. 4B). This is in clear contrast to the condensed chromosomes in many cells expressing RCC1S2,11A-GFP, which never achieved tight congression at the metaphase plate before their segregation in anaphase (Fig. 4B). Although transient overexpression of RCC1S2,11A-GFP caused a dominant negative effect in spindle assembly and chromosome segregation, we were able to select stable cell lines expressing RCC1S2,11A-GFP at levels similar to endogenous RCC1. These cells do not have obvious spindle defects compared to control cells expressing RCC1-GFP.

Table 1.

Quantification of mitotic Swiss 3T3 and tsBN2 cells expressing RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2, 11A-GFP at the permissive temperature

| Metaphase

|

Anaphase

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal spindle and chromosome congretation | Abnormal spindle and/or chromosome congregation | Normal anaphase | Anaphase with lagging chromosomes | |

| RCC1 (3T3) | 74.2% | 5.9% | 17.8% | 2.1% |

| RCC1S2, 11A (3T3) | 17.6% | 66.7% | 9.8% | 5.9% |

| RCC1 (tsBN2) | 57.1% | 19% | 20.9% | 3% |

| RCC1S2, 11A (tsBN2) | 17.4% | 57.6% | 15.9% | 9.1% |

Over 100 mitotic cells transiently overexpressing RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2, 11A-GFP were analyzed to determine the percentage of cells with normal or abnormal metaphase or anaphase.

Figure 4.

Phosphorylation of RCC1 is required for spindle assembly and chromosome segregation. (A) Swiss 3T3 cells overexpressing either RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP were fixed and stained with an anti-α-tubulin antibody (DM1-α) and DAPI. Examples of cells expressing RCC1-GFP with normal spindles and chromosomes or expressing RCC1S2,11A-GFP with defects in chromosome arm congression (white arrowhead), metaphase spindle (blue arrowhead), and chromosome segregation are shown (white arrow pointing to a lagging chromosome). (B) Time-lapse microscopy of Swiss 3T3 cells overexpressing RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP from prometaphase to anaphase. Chromosomes in RCC1S2,11A-GFP-expressing cells failed to congress properly before segregation. (C) Temperature-shift experiments. tsBN2 cells stably expressing RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP were arrested with nocodazole at the permissive temperature (37°C). After a further incubation at 39.5°C (to inactivate the endogenous RCC1), nocodazole was washed out and spindle assembly and chromosome segregation were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Representative metaphase, anaphase, and telophase cells fixed 40min after nocodazole washout are shown (arrow pointing to lagging chromosomes). Bars, 10μm.

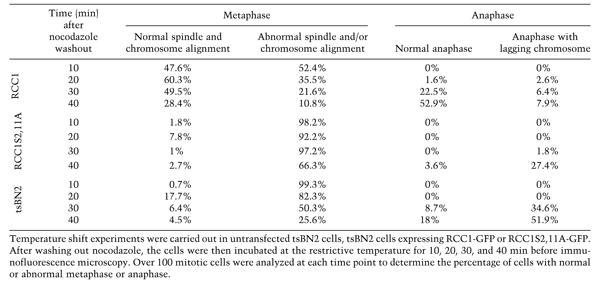

To analyze the mitotic defects caused by RCC1S2, 11A-GFP in more detail, we carried out temperature-shift experiments to inactivate the endogenous RCC1 in tsBN2 cells stably expressing RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2, 11A-GFP at similar levels. The cells were first arrested in mitosis at the permissive temperature by nocodazole, and then shifted to 39.5°C to inactivate endogenous RCC1. Subsequently, nocodazole was washed out to allow spindle assembly in the absence of endogenous RCC1. We fixed and stained the cells with an anti-α-tubulin antibody and DAPI at 10, 20, 30, or 40 min after nocodazole washout. Cells expressing RCC1S2,11A-GFP exhibited severe defects in spindle assembly and chromosome segregation (Fig. 4C). Quantification revealed that only ∼2% of mitotic cells assembled normal metaphase spindles 10min after nocodazole washout. Normal metaphase spindle assembly and chromosome congression never exceeded 8% in the 40min after nocodazole washout. Consequently, only a small percentage of cells underwent anaphase. Among the small number of cells that underwent anaphase, the majority exhibited lagging chromosomes (Fig. 4C; Table 2). As expected, untransfected tsBN2 cells also exhibited severe spindle assembly and chromosome segregation defects (Table 2). In contrast, ∼48% of mitotic cells expressing RCC1-GFP assembled normal metaphase spindles 10min after nocodazole washout. By 40min, over 50% of mitotic cells underwent normal anaphase, with only ∼8% of the mitotic cells exhibiting abnormal anaphase with lagging chromosomes. At this timepoint, only ∼10% of the mitotic cells exhibited defective metaphase spindle and/or chromosome congression (Table 2). Thus, phosphorylation of RCC1 is essential for spindle assembly and chromosome segregation.

Table 2.

Quantification of mitotic untransfected tsBN2 cells or tsBN2 cells expressing RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP at the restrictive temperature

Phosphorylation of RCC1 is required to produce a high RanGTP concentration on mitotic chromosomes in vivo

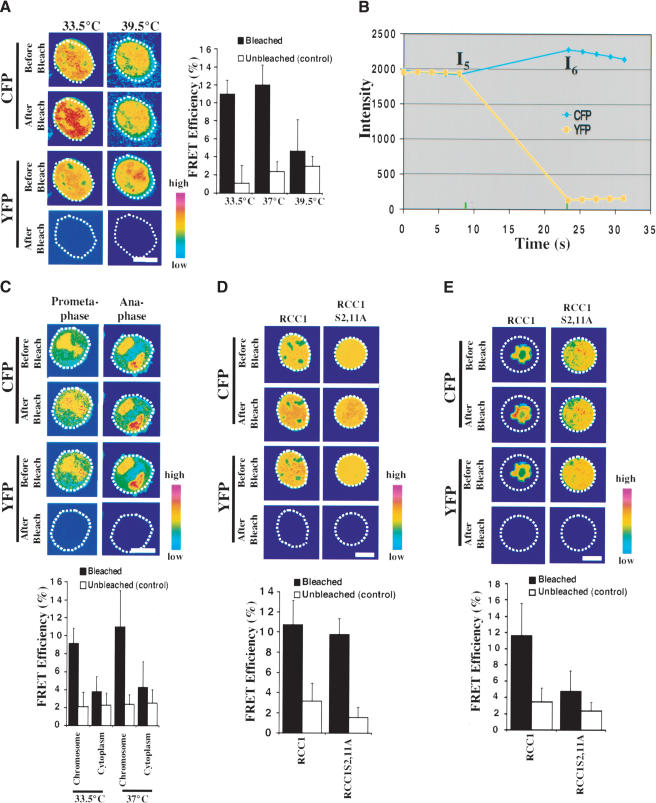

A high RanGTP concentration on mitotic chromosomes has been proposed to be essential for spindle assembly. Because RCC1S2,11A exhibited a reduced binding to mitotic chromosomes (see Fig. 3C), we suspected that this mutant RCC1 might fail to support a high RanGTP concentration on the mitotic chromosomes, thereby causing mitotic defects. To test this, we used fluorescence energy transfer (FRET) to detect RanGTP in vivo. Previous studies have shown that the importin-β-binding domain of importin α (IBB) fused at its C and N termini to yellow (YFP) and cyan (CFP) fluorescent proteins, respectively, is an excellent FRET probe for RanGTP (Kalab et al. 2002). Because the IBB domain is highly flexible, the YFP–IBB– CFP (YIC) protein undergoes intramolecular FRET. However, when importin β is bound to IBB, FRET is inhibited. The binding of RanGTP to importin β dissociates it from IBB, thereby restoring FRET of YIC.

We constructed a similar version of the YIC probe in a mammalian expression vector and expressed it in tsBN2 cells. Consistent with previous reports (Kalab et al. 2002), we found that YIC was concentrated in interphase nuclei and on mitotic chromosomes, and that this concentration depends on a functional RCC1 (Fig. 5A,C,E). We grew tsBN2 cells expressing YIC at permissive or restrictive temperatures. Because growth at the restrictive temperature leads to RCC1 degradation and a reduction of RanGTP in interphase nuclei, if YIC can report RanGTP in vivo, we should observe a higher nuclear FRET signal in cells grown at the permissive temperature than cells grown at the restrictive temperature.

Figure 5.

Phosphorylation of RCC1 is essential for production of the RanGTP gradient. (A) YIC FRET reports the existence of RanGTP in the interphase nucleus. tsBN2 cells expressing YIC were incubated at permissive (33.5°C or 37°C) or restrictive (39.5°C) temperatures for 2–3 h before FRET. Images of interphase cells in CFP and YFP before and after photobleaching are shown. White dashed circles outline the interphase nuclei. Histogram shows quantification of FRET: the increase in CFP fluorescence intensity in bleached (black columns) and control unbleached (white columns) cells. (B) A typical quantification curve of FRET. The cell was scanned five times before and after bleaching YFP. Fluorescence intensities (I) of CFP from the last scan before bleaching (I5) and the first scan after bleaching (I6) were used to quantify FRET shown in the histograms. (C) RanGTP is concentrated on mitotic chromosomes in vivo. Images of pro-metaphase and anaphase cells before and after photobleaching are shown. White dashed circles outline mitotic cells. A higher FRET signal was detected on mitotic chromosomes than in the mitotic cytosol (see the histogram below the images). (D) Both RCC1-GFP and RCC1S2,11A-GFP support RanGTP production in interphase nuclei. FRET was carried out in tsBN2 cells expressing RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP grown at 39.5°C for 2–3 h. Similar FRET signals were detected. (E) Phosphorylation of RCC1 is required for the RanGTP gradient production in mitosis. tsNB2 cells expressing RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP were arrested in mitosis at the permissive temperature by nocodazole, and then shifted to 39.5°C for 2–3 h before FRET. Significantly stronger FRET was detected on the mitotic chromosomes in cells expressing RCC1-GFP than cells expressing RCC1S2,11A-GFP.

We used the acceptor-bleaching method (Bastiaens and Jovin 1996; Wouters et al. 1998; Kenworthy 2001; Karpova et al. 2003) and a confocal microscope to detect FRET in the above living cells. When the acceptor YFP of the FRET pair is bleached, an increase in fluorescence signal in the donor CFP indicates the existence of FRET. To quantify FRET, cells were scanned in both CFP and YFP channels five times before and after photobleaching of YFP (Fig. 5B). The increase in CFP fluorescence signal in the nucleus after photobleaching (Fig. 5A, black columns) was compared to the CFP fluctuation in the unbleached cell nucleus (Fig. 5A, white columns; e.g., see the histogram in Fig. 5A). A number of controls were carried out to validate the FRET procedure (see Materials and Methods and Supplemental Material). In cells grown at permissive temperatures (33.5°C and 37°C), we found a significant increase in CFP signal in the nuclei of photobleached cells compared to unbleached controls (Fig. 5A). However, in cells grown at the restrictive temperature (39.5°C), the FRET signal was significantly reduced, indicating the loss of RanGTP in the nuclei due to RCC1 inactivation (Fig. 5A). Thus, YIC can be used to report RanGTP in vivo.

Next, we determined whether RanGTP is concentrated on mitotic chromosomes of tsBN2 cells at permissive temperatures. Although YIC was concentrated on the condensed chromosomes, a significant amount of YIC was diffusely distributed throughout the mitotic cytoplasm (Fig. 5C). Our calibration experiments showed that YIC with average fluorescence intensity between 800 and 2800 (arbitrary fluorescence units) in the interphase nuclei exhibited similar FRET efficiency (see Supplementary Fig. S5). Therefore, we chose mitotic cells that had the average fluorescence intensity of cytoplasmic YIC between 800 and 1800 for FRET analyses. In these cells the average YIC fluorescence intensity on the mitotic chromosomes did not exceed 2800. We detected a significantly stronger FRET signal on the condensed chromosomes than that of the mitotic cytoplasm (Fig. 5C). Thus, a high RanGTP concentration is maintained on the mitotic chromosomes at the permissive temperature in vivo.

Because RCC1 is only phosphorylated in mitosis, RCC1S2,11A-GFP should support RanGTP production as efficiently as RCC1-GFP in interphase nuclei in the absence of endogenous RCC1. Indeed, similar FRET signals were detected in the interphase nuclei of tsNB2 cells expressing either RCC1S2,11A-GFP or RCC1-GFP at 39.5°C (Fig. 5D). Control experiments showed that FRET was not caused by photobleaching of the GFP fused to RCC1 in these cells (see Supplementary Fig. S4). Therefore, RCC1S2,11A-GFP is fully active in producing RanGTP in interphase.

To determine whether RCC1S2,11A-GFP can maintain a high RanGTP concentration on the condensed chromosomes in mitosis at the restrictive temperature, we carried out FRET in mitotic tsBN2 cells stably expressing either RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP. The cells were arrested in mitosis by nocodazole at the permissive temperature, followed by a further incubation at the restrictive temperature to inactivate endogenous RCC1 before FRET. We found a significantly diminished FRET signal on the chromosomes of tsBN2 cells expressing RCC1S2,11A-GFP compared to cells expressing RCC1-GFP (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, our analyses showed that RCC1S2,11D-GFP, which mimics phosphorylated RCC1, supported RanGTP production as efficiently as wild-type RCC1-GFP at the restrictive temperature in both interphase and mitosis (see Supplementary Fig. S3B). Therefore, phosphorylation of RCC1 is essential for generating and maintaining a high RanGTP concentration on mitotic chromosomes.

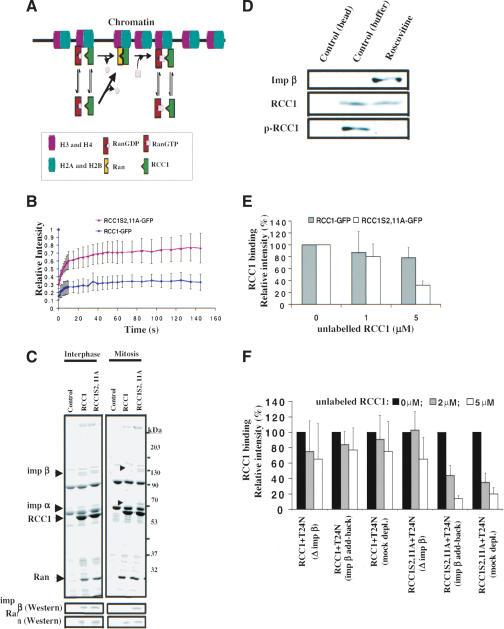

Nonphosphorylatable RCC1 fails to bind to mitotic chromosomes stably as a binary complex with Ran

Our FLIP analysis showed that phosphorylation of RCC1 increases its binding affinity to mitotic chromosomes (Fig. 3C). Because chromatin moderately stimulates the GEF activity of RCC1 in vitro (Nemergut et al. 2001), phosphorylation of RCC1 should contribute to RanGTP gradient formation by simply increasing the residence time of RCC1 on mitotic chromosomes. Although this simple mechanism could explain why RCC1 phosphorylation is necessary for RanGTP formation on the mitotic chromosomes, our recent findings suggest that phosphorylation of RCC1 could contribute to the formation of RanGTP gradient by an additional means. We have shown that RCC1 is a highly mobile enzyme that couples chromosome binding to its GEF activity through the binary complex of RCC1–Ran, an intermediate of the GEF reaction that binds to chromatin stably. Nucleotide exchange on Ran is required to dissociate the binary complex into RanGTP and RCC1, which in turn dissociate from chromatin (Li et al. 2003). This chromosome-coupled exchange mechanism (Fig. 6A) can contribute to RanGTP formation on the mitotic chromosomes in vivo (Li et al. 2003). We reasoned that the weakened interaction between RCC1S2,11A and chromosomes could destabilize the binding of the binary complex of RCC1S2,11A–Ran to chromosomes, thereby disrupting the chromosome-coupled nucleotide exchange on Ran and the production of a high RanGTP concentration on the condensed chromosomes.

Figure 6.

Importin α and β negatively regulate RanGTP production in mitosis. (A) The chromosome-coupled exchange mechanism. Core histones, Ran, and RCC1 are shown. As individual proteins, Ran and RCC1 weakly interact with chromatin via histones H3/H4 and histones H2A/H2B, respectively. However, formation of the binary complex of RCC1–Ran during nucleotide exchange allows the binary complex to bind to chromatin stably and irreversibly. Nucleotide exchange on Ran dissociates the binary complex into RanGTP and RCC1, thereby coupling RanGTP production to mitotic chromosomes. (B) FRAP analysis of RCC1 mobility in vivo. RanT24N was injected into the mitotic cytosol of cells expressing RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11-GFP followed by FRAP of RCC1 on mitotic chromosomes. RCC1-GFP, but not RCC1S2,11A-GFP, was immobilized on mitotic chromosomes. Error bars show S.D. from at least five independent experiments. (C) Phosphorylation of RCC1 in mitosis prevents its interaction with importin α and β. Purified 6His-RCC1 or 6His-RCC1S2,11A was incubated with interphase or mitotic egg extracts. Both forms of RCC1 bound to similar amounts of Ran. The 95-kD and 50-kD proteins that specifically interacted with RCC1S2,11A in mitosis (see arrowheads) were identified by microsequencing as importin α and β, respectively. Western blotting further confirmed the identity of importin β and Ran. (D) Unphosphorylated RCC1 binds to importin β in mitotic HeLa cells. Roscovitine or control buffer was used to inhibit Cdc2 kinase activity in the mitotic HeLa cells. Beads alone or beads bound to 6His-RanT24N were used to pull down RCC1 from the HeLa cell lysates. Western blotting revealed that roscovitine blocked RCC1 phosphorylation (as revealed by phosphospecific antibody, p-RCC1), which allowed RCC1 to bind importin β. (E) Competition experiments. The binding of RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP to mitotic chromosomes in the presence of RanT24N was completed using an increasing concentration of unlabeled 6His-RCC1 or 6His-RCC1S2,11A, respectively. Histograms show the relative fluorescence intensity of GFP-labeled RCC1 on mitotic chromosomes under different conditions. RCC1S2,11A-GFP exhibits a weaker binding than RCC1-GFP. (F) Importin β inhibits the binding of RCC1S2,11A to chromosomes. Egg extracts depleted of importin β with or without add-back of importin β along with mock-depletion controls were used to assemble mitotic chromosomes in the presence of RanT24N. The binding of RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP to the chromatin in the presence of unlabeled RCC1 competitors is quantified. Depletion of importin β allows binding of RCC1S2,11A-GFP to chromatin as strongly as RCC1-GFP.

To assay whether the RCC1S2,11A–Ran binary complex has a reduced interaction with mitotic chromosomes compared to RCC1–Ran in live cells, we needed to trap the binary complex by preventing nucleotide exchange on Ran. Previous studies have shown that RanT24N has a greatly reduced affinity for guanine nucleotide, and that it can bind and trap RCC1 in the binary complex due to lack of nucleotide exchange (Dasso et al. 1994; Kornbluth et al. 1994; Klebe et al. 1995; Lounsbury et al. 1996). Indeed, we have shown that RanT24N can immobilize RCC1-GFP to chromatin due to the formation of binary complexes that bind to chromosomes stably (Li et al. 2003). Because RanT24N binds to RCC1 and RCC1S2,11A with similar affinities (Supplementary Fig. S2), we reasoned that if the binary complex of RCC1S2,11A–Ran failed to bind to mitotic chromosomes stably, RanT24N would not immobilize RCC1S2,11A to chromosomes in mitosis. To test this, we microinjected RanT24N into mitotic Swiss 3T3 cells expressing either RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP. The mobility of RCC1 was then measured by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP). One area on the mitotic chromosomes was photobleached, and the recovery of RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP in the bleached region was measured over time. A lack of recovery indicates that the protein is immobilized on the mitotic chromosomes. Consistent with our previous finding (Li et al. 2003), microinjection of RanT24N immobilized wild-type RCC1-GFP on mitotic chromosomes due to the formation of a binary complex of RCC1–RanT24N that cannot undergo nucleotide exchange (Fig. 6B). In contrast, microinjection of the same amount of RanT24N failed to immobilize RCC1S2,11A-GFP to the mitotic chromosomes (Fig. 6B). Therefore, phosphorylation of RCC1 in mitosis is required for the stable binding of the binary complex of RCC1–Ran to mitotic chromosomes.

Phosphorylation of RCC1 prevents its binding to importin α and β in mitosis

To understand how phosphorylation enhances the binding of RCC1 to mitotic chromosomes, we examined whether phosphorylation might change the affinity of RCC1 toward its interacting proteins. Purified 6His-RCC1 or 6His-RCC1S2,11A was incubated with either mitotic or interphase Xenopus egg extracts. Proteins bound to RCC1 were isolated using Ni-agarose and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining. As expected, mutant and wild-type RCC1 bound to similar amounts of Ran in interphase and mitosis (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, two proteins of ∼50kD and ∼95 kD specifically bound to RCC1S2,11A but not to wild-type RCC1 in mitotic egg extracts (Fig. 6C). In contrast, similar amounts of the two proteins were bound to both wild-type and mutant RCC1 in interphase egg extracts (Fig. 6C). Microsequencing identified the two proteins as importin α and β. Thus, the amount of RanGTP in the mitotic Xenopus egg extract is insufficient to displace RCC1 from importin α/β; instead, Cdc2 phosphorylation of RCC1 is necessary to prevent importin α/β to bind to RCC1. Consistent with this, a phospho-mimic form of RCC1S2,11D does not bind to importin α and β (see Supplementary Fig. S3C). To determine whether phosphorylation of RCC1 also prevents the binding of RCC1 to importin α/β in mitotic HeLa cells, we arrested HeLa cells in mitosis with nocodazole, and then treated the mitotic HeLa cells with either the Cdc2 inhibitor roscovitine or buffer control. RCC1 was isolated from the cell lysates using 6His-RanT24N as described above. Consistent with our earlier finding, roscovitine blocked RCC1 phosphorylation in mitotic HeLa cells (Fig. 6D). Moreover, only the unphosphorylated RCC1 interacted with importin β in the mitotic HeLa cells (Fig. 6D). Quantification revealed that the unphosphorylated RCC1 interacted with importin β at ∼1:1 stoichiometry in the HeLa cell lysate (data not shown). Thus, the amount of RanGTP in the mitotic HeLa cells is insufficient to displace importin α/β from unphosphorylated RCC1, and Cdc2 phosphorylation of human RCC1 is required to block the interaction between RCC1 and importin α/β in mitosis.

Importin α and β destabilize the binding of the binary complex of RCC1S2,11A–Ran to mitotic chromatin

The binding of importin α and β to the NLS of RCC1 does not inhibit the GEF activity of RCC1 in vitro (Talcott and Moore 2000). However, because the N terminus (amino acids 1–28) of RCC1 contains the NLS (Nemergut and Macara 2000; Talcott and Moore 2000) and is required for RCC1 interaction with chromosomes (Moore et al. 2002), we reasoned that importin α and β binding to the NLS of RCC1 might inhibit RCC1 binding to chromosomes in mitosis. This could destabilize the binding of the binary complex of RCC1–Ran to mitotic chromatin, thereby disrupting chromosome-coupled nucleotide exchange on Ran.

We previously developed a competition assay to study the interaction of RCC1 with chromatin using mitotic Xenopus egg extracts (Li et al. 2003). We first applied this assay to determine whether the binary complex of RCC1S2,11A–Ran had a reduced affinity toward chromosomes compared to the binary complex of RCC1–Ran. Demembranated Xenopus sperm were added to mitotic egg extracts in the presence of RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP and increasing concentrations of 6His-RCC1 or 6His-RCC1S2,11A as competitors, respectively. We used purified RanT24N to trap RCC1 in a stable binary complex. The binding of RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP to chromatin was quantified (Li et al. 2003). We found that RCC1-GFP remained bound to chromatin even in the presence of 5 μM competitor 6His-RCC1, whereas the same concentration of competitor 6His-RCC1S2,11A efficiently competed for the binding of the RCC1S2,11A-GFP to chromosomes (Fig. 6E). This suggests that whereas the binary complex of RCC1–RanT24N binds to chromosomes stably, the binary complex of RCC1S2,11A–RanT24N does not. This is consistent with the finding in living cells (see Fig. 6B).

Next, we determined whether importin α and β in egg extracts could inhibit the binding of RCC1S2,11A–RanT24N binary complex to chromosomes. We depleted importin β using purified ZZ-tagged IBB and repeated the above assay. Depleting importin β should prevent importin α binding to the NLS of RCC1. Western blotting showed that over 90% of importin β in the egg extract was depleted (data not shown). We found that importin β depletion allowed RCC1S2,11A-GFP to interact with chromosomes as stably as RCC1-GFP in the presence of RanT24N (Fig. 6F). Adding back purified importin β reestablished the reduced binding of RCC1S2,11A-GFP to chromosomes (Fig. 6F). This suggests that the binding of importin α and β to RCC1S2,11A in mitosis prevents the binary complex of RCC1S2,11A–RanT24N from binding to mitotic chromosomes stably. Therefore, nonphosphorylatable RCC1 cannot couple RanGTP production on mitotic chromosomes to produce a high RanGTP concentration.

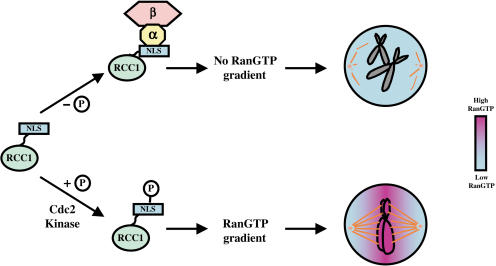

The lack of a nuclear envelope in mitosis of mammalian cells permits importin α/β binding to RCC1 in a common cytoplasm. We show that the amount of RanGTP in mitotic HeLa cells is insufficient to displace importin α/β from the unphosphorylated RCC1, and that the binding of importin α/β inhibits RCC1 to produce RanGTP on mitotic chromosomes. Importantly, Cdc2 phosphorylation of the NLS of RCC1 prevents the binding of importin α/β to RCC1, which allows RCC1 to interact with mitotic chromatin productively to generate a high RanGTP concentration. Based on our findings, we propose that Cdc2 kinase phosphorylation of RCC1 is essential for the placement of a high RanGTP concentration on the mitotic chromosomes, which in turn is necessary to stimulate spindle assembly (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

A model. The N terminus of RCC1 (green) contains an NLS and is required for RCC1 to bind to chromatin. In mitosis, binding of importin α (yellow) and β (pink) to the NLS interferes with RCC1 binding to mitotic chromosomes. Therefore, phosphorylation of RCC1 is required to prevent the binding of importin α and β, thereby allowing RCC1 to bind to mitotic chromosomes with sufficient affinity to produce RanGTP on the chromosome. A high RanGTP concentration (purple) established on mitotic chromosomes (gray) is required for spindle assembly in mitosis.

Discussion

The Ran system has several functions in cell division (Dasso 2002), yet whether or how this system is regulated by the cell-cycle machinery and vice versa in mitosis is poorly understood. Likewise, although a high RanGTP concentration on mitotic chromosomes is thought to be essential for spindle assembly, there has been no in vivo evidence of such a RanGTP concentration. Therefore, whether RanGTP on condensed chromosomes is required for mitotic spindle assembly in vivo has remained unclear. We show here that the cell-cycle machinery regulates RanGTP production by phosphorylating the nucleotide exchange factor RCC1 in mitosis. Our findings reveal a mechanism of communication between the cell-cycle machinery and the Ran-signaling pathway in mitosis.

RanGTP in spindle assembly, chromosome arm congression, and segregation

Using FRET, we demonstrated that a high RanGTP concentration indeed exists on mitotic chromosomes in living cells. More importantly, phosphorylation of RCC1 is essential for the production of this RanGTP in mitosis. We show that loss of the high RanGTP concentration due to the lack of RCC1 phosphorylation severely disrupts spindle assembly in mitotic cells without affecting chromosome condensation. Although microtubules are polymerized in mitotic cells lacking RanGTP, they are disorganized (see Fig. 4C), and >90% of the cells fail to establish bipolar spindles. These defects in living cells are consistent with the effects of RanGTP on microtubules previously established using Xenopus egg extracts (Carazo-Salas et al. 2001; Wilde et al. 2001). Interestingly, we also observed a prominent chromosome arm congression defect in cells where overall chromosome alignment has occurred on the bipolar spindles. This suggests that RanGTP may regulate chromosome arm congression in mitosis. Chromokinesin (Wang and Adler 1995), which controls chromosome alignment and arm congression in metaphase, is found in interphase nuclei (Antonio et al. 2000; Funabiki and Murray 2000; Levesque and Compton 2001). Indeed, a recent study shows that this kinesin is regulated positively and negatively by RanGTP and importin α/β, respectively (Trieselmann et al. 2003).

The contribution of RCC1 phosphorylation toward RanGTP production in mitosis

In mitosis, RCC1 is found on condensed chromosomes (Moore et al. 2002; Li et al. 2003), whereas proteins involved in RanGTP hydrolysis such as RanGAP1 are found both on kinetochores and in the cytoplasm (Joseph et al. 2002). Although it remains unclear how RanGTP hydrolysis may contribute toward shaping the RanGTP gradient in mitosis, we have begun to understand how RCC1 may catalyze RanGTP production on mitotic chromosomes. RCC1 is a highly mobile enzyme that continuously binds to and dissociates from chromosomes (Li et al. 2003). Two mechanisms appear to be used by RCC1 in producing a high RanGTP concentration on condensed chromosomes. In one mechanism, chromosomes play a role in moderately stimulating the GEF activity of RCC1 (Nemergut et al. 2001). Therefore, chromosome-bound RCC1 should produce more RanGTP than free RCC1 in vivo. We will refer to this mechanism as chromosome-stimulated exchange. We recently showed that RCC1 also uses a chromosome-coupled exchange mechanism to ensure that mobile RCC1 couples chromosome binding to RanGTP production (Li et al. 2003). The stable binding of the binary complex RCC1–Ran to chromosomes mediates this mechanism. Because nucleotide exchange is required for the binary complex to dissociate from chromosomes as RanGTP and RCC1, the chromosome-coupled exchange mechanism provides another means to ensure the production of a high RanGTP concentration on the mitotic chromosomes.

Although the chromatin/histones may contribute toward RanGTP production by other means, both mechanisms described above require RCC1 to interact with chromatin with an appropriate affinity. Our FLIP analysis showed that wild-type RCC1 dissociates from mitotic chromosomes more slowly compared to the nonphosphorylatable RCC1 in vivo. Therefore, phosphorylation of RCC1 increases its binding affinity toward mitotic chromosomes. We propose that mitotic phosphorylation of RCC1 contributes to RanGTP production by affecting both the chromosome-stimulated exchange and the chromosome-coupled exchange. We have provided evidence that phosphorylation is required for the stable binding of the binary complex of RCC1–Ran to mitotic chromosomes both in vivo and in vitro. One future challenge will be to understand the relative contributions of each of the two mechanisms toward RanGTP production in mitosis.

Regulation of RanGTP production in mitosis

Mitosis in higher eukaryotes occurs in the absence of a nuclear envelope. The lack of nuclear compartmentalization permits importin α and β to bind to the NLS of its cargo such as RCC1. We have shown that the amount of RanGTP present in the mitotic HeLa cells is insufficient to displace importin α/β from the unphosphorylated RCC1 (Fig. 6D). The binding of importin α/β to the NLS of RCC1 does not affect the intrinsic GEF activity of RCC1 (Talcott and Moore 2000). However, it hinders the binding of RCC1 to mitotic chromosomes, because the N terminus of RCC1 containing the NLS (Nemergut and Macara 2000; Talcott and Moore 2000) is important in mediating the binding of RCC1 to chromosomes (Moore et al. 2002).

Several lines of our evidence suggest that phosphorylation of RCC1 is essential for overcoming the inhibitory binding of importin α/β to RCC1, thereby allowing RCC1 to couple RanGTP production to mitotic chromosomes. First, biochemical experiments show that RCC1S2,11A, but not wild-type RCC1 or phosphomimic RCC1S2,11D, binds to importin α/β in mitotic Xenopus egg extracts. Second, unphosphorylated human RCC1 binds to importin β in mitotic HeLa cells. Third, FLIP analysis shows that RCC1S2,11A-GFP dissociates from mitotic chromosomes more rapidly than RCC1-GFP in vivo. Fourth, FRAP experiments suggest that the binary complex of RCC1S2,11A–RanT24N fails to bind to the mitotic chromosomes stably in living cells. Fifth, biochemical assays using mitotic Xenopus egg extracts show that importin β inhibits the ability of the binary complex of RCC1S2,11A–RanT24N, but not RCC1–RanT24N, to bind to the mitotic chromosomes stably. Finally, although RCC1S2,11A supports RanGTP production in interphase nuclei, it fails to support the formation of a high RanGTP concentration on the mitotic chromosomes.

We have shown that phosphorylation of either S2 or S11 of human RCC1 is sufficient for its function in vivo (Fig. 2C). S11 is within the previously defined NLS of human RCC1, and S2 is only five amino acids away from the NLS (Talcott and Moore 2000). Therefore, phosphorylation of S2 or S11 would introduce a negative charge in or near the overall positively charged NLS of RCC1. Our studies show that this negative charge disrupts the interaction between RCC1 and importin α/β in mitosis, allowing RCC1 to interact with mitotic chromosomes with higher affinity.

Regulated interaction between NLS and import receptors by phosphorylation is known to relay cellular signals by controlling protein localization in interphase (O'Shea and Kaffman 1999). For example, phosphorylation of serines in the vicinity of the NLS of the transcription factor Swi5 by Cdc28, the yeast homolog of Cdc2, prevents the nuclear import of Swi5 (Moll et al. 1991). Remarkably, we reveal here that a similar mechanism is used in mitosis to regulate the binding of RCC1 to mitotic chromosomes in mammalian cells. Our study represents the first example of how the cell-cycle machinery can regulate the Ran system in mitosis.

Materials and methods

Molecular cloning, protein expression and purification, and antibodies

GeneEditor (Promega) was used to create point mutations of human RCC1. The mutant and wild-type RCC1 were expressed in mammalian cells and bacteria using pEGFP-N3 (Clontech) and pEGFP (or pET15b, Novagen), respectively. ECFP was cloned into Kpn1 and BamHI sites of pEYFP-C1 vector (Clontech). Then, the IBB domain was cloned in frame between EYFP and ECFP in BglII and SalI sites to make YIC. YFP–IBB and IBB–CFP vectors were constructed in pEYFP-N1 and pECFP-C1, respectively. ZZ-IBB was constructed by cloning ZZ into pET30a and then fusing IBB in-frame to the C terminus of ZZ. The bacterially expressed proteins were purified using Ni-agarose beads (Li et al. 2003). Antibodies against RCC1 and against phosphorylated RCC1 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotech and produced and purified at Zymed, respectively.

RCC1 phosphorylation, GEFassay, and interacting proteins

Purified wild-type or mutant 6His-RCC1 (∼0.4 mg/mL final) was incubated with Xenopus cytostatic factor (CSF) arrested or interphase egg extracts (Murray 1991) in the presence of 100 μCi/μmol γ-32p-ATP and 100 μM ATP. The proteins were reisolated using Ni-agarose and washed with XB buffer (10mM HEPES at pH 7.7, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 50 mM sucrose, 5 mM EGTA) containing 20mM imidazole, followed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. For the RCC1 phosphorylation study in mitotic HeLa cells, the cells were synchronized in mitosis using nocodazole (400 nM). Cell lysates were made from both mitotic-arrested and unsynchronized cells using lysis buffer (50mM Tris at pH 7.5, 250mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 10 μg/mL each of chymostatin, leupeptin, and pepstatin, 10mM NaF, 30mM Na3P2O7, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 1 mM GTP). To determine whether RCC1 was phosphorylated by Cdc2 kinase in HeLa cells, the mitotic-arrested cells were treated with 50μM roscovitine or control buffer. Cdc2 kinase activity in cell lysates made from these cells was assayed as described (Felix et al. 1989). RCC1 in the cell lysate was isolated using purified 6His-RanT24N. For GEF assays, 0.44 nM purified 6His-RCC1 or 6His-RCC1S2,11A was treated with buffer or Cdc2 kinase (New England BioLab), and then used to catalyze the nucleotide release of 1 μM RanGDP[H3] as described (Dasso et al. 1994). To identify proteins that interact with RCC1 specifically in interphase or mitosis, purified 6His-RCC1 or 6His-RCC1S2,11A (∼0.2 mg/mL final) was added to interphase or CSF-egg extracts. The proteins were isolated using Ni-agarose and washed with XB buffer containing 20mM imidazole. The 50-kD and 95-kD proteins that specifically bound to 6His-RCC1S2,11A in CSF-egg extracts were excised and identified in the HHMI mass spectrometry laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, by peptide mass fingerprinting (using MSFit at http://prospector.ucsf.edu).

Analyzing cells expressing RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP

Swiss 3T3 and tsBN2 cells were transiently transfected with RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A-GFP. At 36 h after transfection, cells were fixed and stained. To image chromosome behavior in mitosis, Swiss 3T3 cells were cultured on Lab-TekII chambered coverglasses (Nalge Nunc International) at 37°C in a temperature controller (Nikon) mounted on the Eclipse TE200 microscope (Nikon). Movies were made using an Orca-II camera driven by the MetaMorph Imaging System (Universal Imaging). For temperature-shift experiments, tsBN2 cells were first arrested in mitosis using 200 nM nocodazole for 4 h at the permissive temperature (37°C), and then shifted to the restrictive temperature (39.5°C) for 2–3 h to inactivate endogenous RCC1. The cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy after nocodazole washout. FLIP, FRAP, and microinjection of RanT24N were performed as described (Li et al. 2003).

FRET analysis

A Zeiss LSM510confocal microscope was used for FRET studies using the acceptor bleaching method as described (Karpova et al. 2003) with modifications. Cells were incubated in a Focht Chamber System 2 (Bioptechs) at permissive (33.5°C or 37°C) or restrictive (39.5°C) temperatures during FRET experiments. The pinhole was set to 1 μm and 1.61 μm for YFP and CFP, respectively. For imaging, PMT gain was set at 400–500, which prevented cross-talk between YFP and CFP channels under our expression conditions (see Supplementary Fig. S4A). Five images were collected consecutively at 0.15% of the laser intensity in CFP and YFP channels before and after bleaching of YFP by scanning 100 times at 75% laser intensity. As controls, unbleached cells in the same field were used to determine the background CFP fluctuations during FRET. Fluorescence intensity was measured in the whole nucleus, on the condensed chromosomes (including pro-metaphase, metaphase, and anaphase), and in the mitotic cytosol. FRET efficiency was calculated as EF% = (I6 – I5) × 100/I6 (Karpova et al. 2003). I5 and I6 represent the CFP fluorescence intensity of the fifth and sixth images immediately before and after photobleaching of YFP. The prebleach CFP fluctuation calculated from I1 through I5 was ±1%. At least 10cells were analyzed in each FRET or control experiment from at least three different days. The FRET efficiency is expressed as mean percentage fluorescence increase ± S.D.

Assays in Xenopus egg extracts

Mitotic chromosomes were assembled from demembranated Xenopus sperm in CSF-egg extracts in the presence of 0.5 μM RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2,11A (Li et al. 2003). RanT24N was added to the reactions (40μM final) to trap RCC1 in a stable binary complex. Unlabeled 6His-RCC1 or 6His-RCC1S2,11A (0–5 μM) was used to compete for the binding of RCC1-GFP or RCC1S2, 11A-GFP to mitotic chromatin, respectively. The amount of RCC1-GFP associated with the chromatin was quantified as described (Li et al. 2003). To deplete importin β, purified ZZ-IBB (2 mg/mL final) was added to CSF-egg extracts. ZZ-IBB and its bound importin β were removed using IgG Sepharose beads. This process was repeated once to deplete over 90% of importin β in the CSF-egg extracts. In add-back experiments, purified 6His-importin β was added to the importin-β-depleted egg extracts to the endogenous level.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ona Martin for skillful technical support, Drs. Gerry Saxton and Mike McCaffery (Integrated Imaging Center, JHU) for help with the FRET analysis, Drs. Arnie Falick and David King (HHMI) for mass spectroscopy analysis, and Kan Cao for many helpful discussions. We are grateful to Dr. Doug Koshland and the members of the Zheng lab for critical reading of the manuscript. Supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1177304.

References

- Antonio C., Ferby, I., Wilhelm, H., Jones, M., Karsenti, E., Nebreda, A.R., and Vernos, I. 2000. Xkid, a chromokinesin required for chromosome alignment on the metaphase plate. Cell 102: 425–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaoutov A. and Dasso, M. 2003. The Ran GTPase regulates kinetochore function. Dev Cell. 5: 99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaens P.I.H. and Jovin, T.M. 1996. Microspectroscopic imaging tracks the intracellular processing of a signal transduction protein: Fluorescent-labeled protein kinase CβI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93: 8407–8412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbao-Cortes D., Hetzer, M., Langst, G., Becker, P.B., and Mattij, I.W. 2002. Ran binds to chromatin by two distinct mechanisms. Curr. Biol. 12: 1151–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carazo-Salas R.E., Guarguaglini, G., Gruss, O.J., Segref, A., Karsenti, E., and Mattaj, I.W. 1999. Generation of GTP-bound Ran by RCC1 is required for chromatin-induced mitotic spindle formation. Nature 400: 178–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carazo-Salas R.E., Gruss, O.J., Mattaj, I.W., and Karsenti, E. 2001. RanGTP coordinates the regulation of microtubule nucleation and dynamics during mitotic spindle assembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 3: 228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole C.N. and Hammell, C.M. 1998. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: Driving and directing transport. Curr. Biol. 8: R368–R372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasso M. 2002. The Ran GTPase: Theme and variations. Curr. Biol. 12: R502–R508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasso M., Seki, T., Azuma, Y., Ohba, T., and Nishimoto, T. 1994. A mutant form of the Ran/TC4 protein disrupts nuclear function in Xenopus laevis egg extracts by inhibiting the RCC1 protein, a regulator of chromosome condensation. EMBO J. 13: 5732–5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix M.A., Pines, J., Hunt, T., and Karsenti, E. 1989. A postribosomal supernatant from activated Xenopus eggs that displays posttranslationally regulated oscillation of its cdc2 mitotic kinase activity. EMBO J. 8: 3059–3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabiki H. and Murray, A.W. 2000. The Xenopus chromokinesin Xkid is essential for metaphase chromosome alignment and must be degraded to allow anaphase chromosome movement. Cell 102: 411–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlich D., Seewald, M.J., and Ribbeck, K. 2003. Characterization of Ran-driven cargo transport and the RanGTPase system by kinetic measurements and computer simulation. EMBO J. 22: 1088–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruss O.J., Carazo-Salas, R.E., Schatz, C.A., Guarguaglini, G., Kast, J., Wilm, M., Bot, N.L., Vernos, I., Karsenti, E., and Mattaj, I.W. 2001. Ran induces spindle assembly by reversing the inhibitory effect of importin a on TPX2 activity. Cell 104: 83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarguaglini G., Renzi, L., D'Ottavio, F., Di Fiore, B., Casenghi, M., Cundari, E., and Lavia, P. 2000. Regulated Ran-binding protein 1 activity is required for organization and function of the mitotic spindle in mammalian cells in vivo. Cell Growth Differ. 11: 455–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetzer M., Bilbao-Cortes, D., Walther, T.C., Gruss, O.J., and Mattaj, I.W. 2000. GTP hydrolysis by Ran is required for nuclear envelope assembly. Mol. Cell 5: 1013–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph J., Tan, S.-H., Karpova, T.S., McNally, J.G., and Dasso, M. 2002. SUMO-1 targets RanGAP1 to kinetochores and mitotic spindles. J. Cell Biol. 156: 595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalab P., Pu, R., and Dasso, M. 1999. The ran GTPase regulates mitotic spindle assembly. Curr. Biol. 9: 481–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalab P., Weis, K., and Heald, R. 2002. Visualization of a Ran-GTP gradient in interphase and mitotic Xenopus egg extracts. Science 295: 2452–2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpova T.S., Baumann, C.T., He, L., Wu, X., Grammer, A., Lipsky, P., Hager, G.L., and McNally, J.G. 2003. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer from cyan to yellow fluorescent protein detected by acceptor photobleaching using confocal microscopy and a single laser. J. Microscopy 209: 56–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenworthy A.K. 2001. Imaging protein–protein interactions using fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy. Methods 24: 289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebe C., Prinz, H., Wittinghofer, A., and Goody, R.S. 1995. The kinetic mechanism of Ran-nucleotide exchange catalyzed by RCC1. Biochemistry 34: 12543–12552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornbluth S., Dasso, M., and Newport, J. 1994. Evidence for a dual role for TC4 protein in regulating nuclear structure and cell cycle progression. J. Cell Biol. 125: 705–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque A.A. and Compton, D.A. 2001. The chromokinesin Kid is necessary for chromosome arm orientation and oscillation, but not congression, on mitotic spindles. J. Cell Biol. 154: 1135–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.Y., Wirtz, D., and Zheng, Y. 2003. A mechanism of coupling RCC1 mobility to RanGTP production on the chromatin in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 160: 635–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lounsbury K., Richards, S., Carey, K., and Macara, I. 1996. Mutations within the Ran/TC4 GTPase. Effects on regulatory factor interactions and subcellular localization. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 32834–32841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattaj I. and Englmeier, L. 1998. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: The soluble phase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67: 265–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll T., Tebb, G., Surana, U., Robitsch, H., and Nasmyth, K. 1991. The role of phosphorylation and the CDC28 protein kinase in cell cycle regulated nuclear import of S. cerevisiae transcription factor SWI5. Cell 66: 743–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J.D. 2001. The Ran-GTPase and cell-cycle control. BioEssays 23: 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore W.J., Zhang, C., and Clarke, P.R. 2002. Targeting of RCC1 to chromosomes is required for proper mitotic spindle assembly in human cells. Curr. Biol. 12: 1442–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray A.W. 1991. Cell cycle extracts. Meth. Cell Biol. 36: 581–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachury V.M., Maresca, T.J., Salmon, W.C., Waterman-Storer, C.M., Heald, R., and Weis, K. 2001. Importin β is a mitotic target of the small GTPase Ran in spindle assembly. Cell 104: 95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemergut M. and Macara, I.G. 2000. Nuclear import of the Ran exchange factor, RCC1, is mediated by at least two distinct mechanisms. J. Cell Biol. 149: 835–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemergut M.E., Mizzen, C.A., Stukenberg, T., Allis, C.D., and Macara, I.G. 2001. Chromatin docking and exchange activity enhancement of RCC1 by histones H2A and H2B. Science 292: 1540–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitani H., Ohtsubo, M., Yamashita, K., Iida, H., Pines, J., Yasudo, H., Shibata, Y., Hunter, T., and Nishimoto, T. 1991. Loss of RCC1, a nuclear DNA-binding protein, uncouples the completion of DNA replication from the activation of cdc2 protein kinase and mitosis. EMBO J. 10: 1555–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea E.K. and Kaffman, A. 1999. Regulation of nuclear localization: A key to a door. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 15: 291–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren M., Villamarin, A., Shih, A., Coutavas, E., Moore, M.S., LoCurcio, M., Clarke, V., Oppenheim, J.D., D'Eustachio, P., and Rush, M.G. 1995. Separate domains of the Ran GTPase interact with different factors to regulate nuclear protein import and RNA processing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 2117–2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz C.A., Santarella, R., Hoenger, A., Karsenti, E., Mattaj, I.W., Gruss, O.J., and Carazo-Salas, R.E. 2003. Importin α-regulated nucleation of microtubules by TPX2. EMBO J. 22: 2060–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talcott B. and Moore, M.S. 2000. The nuclear import of RCC1 requires a specific nuclear localization sequence receptor, karyopherin α3/Qip. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 10099–10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai M.-Y., Wiese, C., Cao, K., Martin, O.C., Donovan, P.J., Ruderman, J.V., Prigent, C., and Zheng, Y. 2003. A Ran signalling pathway mediated by the mitotic kinase Aurora A in spindle assembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 5: 242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trieselmann N., Armstrong, S., Rauw, J., and Wilde, A. 2003. Ran modulates spindle assembly by regulating a subset of TPX2 and Kid activities including Aurora A activation. J. Cell. Sci. 116: 4791–4798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.Z. and Adler, R. 1995. Chromokinesin: A DNA-binding, kinesin-like nuclear protein. J. Cell Biol. 128: 761–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis K. 2002. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: Cargo trafficking across the border. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14: 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese C., Wilde, A., Moore, M.S., Adam, S.A., Merdes, A., and Zheng, Y. 2001. Role of importin-β in coupling Ran to downstream targets in microtubule assembly. Science 291: 653–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde A. and Zheng, Y. 1999. Stimulation of microtubule aster formation and spindle assembly by the small GTPase Ran. Science 284: 1359–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde A., Lizarraga, S.B., Zhang, L., Wiese, C., Gliksman, N.R., Walczak, C.E., and Zheng, Y. 2001. Ran stimulates spindle assembly by changing microtubule dynamics and the balance of motor activities. Nat. Cell Biol. 3: 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouters F.S., Bastiaens, P.I.H., Wirtz, K.W., and Jovin, T.M. 1998. FRET microscopy demonstrates molecular association of nonspecific lipid transfer protein (nsl-TP) with fatty acid oxidation enzymes in peroxisomes. EMBO J. 17: 7179–7189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. and Clarke, P.R. 2000. Chromatin-independent nuclear envelope assembly induced by Ran GTPase in Xenopus egg extracts. Science 288: 1429–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]