Abstract

Objectives

To investigate whether preoperative risk for delirium moderates the effect of postoperative pain and opioids on the development of postoperative delirium.

Design

Prospective cohort study

Setting

University medical center

Participants

Patients ≥ 65 years of age scheduled for major noncardiac surgery

Measurements

A structured interview was conducted pre- and post-operatively to determine the presence of delirium, defined using the Confusion Assessment Method. We first developed a prediction model to determine which patients were at high vs. low risk for the development of delirium based on preoperative patient data. We then computed a logistic regression model to determine whether preoperative risk for delirium moderates the effect of postoperative pain and opioids on incident delirium.

Results

Of 581 patients, 40% developed delirium on days 1 or 2 after surgery. Independent preoperative predictors of postoperative delirium included lower cognitive status, a history of central nervous system disease, high surgical risk, and major spine and joint arthroplasty surgery. Compared to the patients at low preoperative risk for developing delirium, the relative risk for postoperative delirium for those in the high preoperative risk group was 2.38 (95% CI = 1.67–3.40). A significant three-way interaction indicates that preoperative risk for delirium significantly moderated the effect of postoperative pain and opioid use on the development of delirium. Among patients at high preoperative risk for development of delirium who also had high postoperative pain and received high opioid doses, the incidence of delirium was 72%, compared to 20% among patients with low preoperative risk, low postoperative pain and received low opioid doses.

Conclusions

High levels of postoperative pain and using high opioid doses increased risk for postoperative delirium for all patients. However, the highest incidence of delirium was among patients who had high preoperative risk for delirium and also had high postoperative pain and used high opioid doses.

Introduction

Delirium is an acute confusional state with alterations in attention and consciousness. 1 Approximately 5–52% of older patients who were hospitalized for medical or surgical reasons developed delirium. 2 Delirium may be caused by an underlying medical illness, but for many, the exact etiology is not identifiable. 3 Delirium is considered a geriatric syndrome in which there is a complex interrelationship between baseline patient vulnerability and precipitating factors or insults. 4,5

Preoperative characteristics that predispose older adults to the development of delirium include preoperative cognitive status, functional impairment, sensory impairment, preoperative psychotropic drug use, psychopathological symptoms, institutional residence, greater comorbidity, and the type of surgery. 2,6,7 Typically, predisposing characteristics are not modifiable in the perioperative setting. However, recognition of patients’ preoperative risk for delirium may alert clinicians to identify patients who are at greatest need for postoperative monitoring and therapy. In the postoperative period, pain and medications have been identified as two potential precipitating factors for the occurrence of postoperative delirium because of their potential for profound effects on the central nervous system. 8,9,10 However, it is unclear whether these risk factors affect all patients or only those who are predisposed to be at high-risk for postoperative delirium.

Our study approach is novel in that we aimed to determine not only how preoperative risk identifies which patients may be vulnerable to postoperative delirium, but also, how the risk moderates the association with modifiable postoperative factors. To determine whether preoperative risk for delirium moderates the effect of postoperative pain and opioid use on the development of postoperative delirium, it is critical that valid indicator of preoperative risk is available. Although previous studies have built predictive models for postoperative delirium, 7,11 they have included both pre- and post-operative risks. Thus, these indices do not allow early identification of which patients are at risk for postoperative delirium. Furthermore, these studies were not focused on determining risks for older patients undergoing elective non-cardiac surgery. Therefore, we first developed a prediction model to determine which patients were at greatest risk for the development of delirium based on only preoperative patient data. We then determined whether preoperative risk for delirium moderates the association between postoperative pain and opioids and incident delirium. We hypothesized that pain and opioid increased the incidence of postoperative delirium for patients at high-risk of developing delirium.

Materials & Methods

Patient Recruitment

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for human research, at the University of California, San Francisco, and informed consent was obtained preoperatively from each study patient. This cohort study was conducted from 2002 to 2009 at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Centre. The results presented in this manuscript were the primary analysis from this cohort study. The inclusion criteria were English-speaking patients ≥ 65 years of age who were scheduled for major elective noncardiac surgery requiring anesthesia, and who were expected to remain in the hospital postoperatively for more than 48 hours. Excluded were patients who did not provide or were incapable of providing informed consent.

Neurocognitive and Delirium Assessments

Each patient was interviewed by the same trained research assistant preoperatively and postoperatively on days one and two after surgery. The preoperative interview typically occurred less than one week prior to surgery in the preoperative clinic. During the preoperative interview, in addition to the assessment of medical history, the presence of depressive symptoms, pain, and functional status were also measured. Cognitive status was measured preoperatively using the Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status instrument (TICS) 12 which was adapted from the Mini Mental Status Examination. During both the preoperative and the two postoperative interviews, the presence of delirium was measured using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), a delirium screen instrument. 13 The CAM assessments were performed daily on the first two days after surgery between the hours of 9 am to 12 pm, using a structured interview. In addition, we also evaluated patients’ cognitive status using several neuropsychological tests which included the Word List Learning, the Digit Symbol Test, and the Controlled Verbal Fluency Test. These neuropsychological tests were repeated on the first two postoperative days. Many neuropsychological tests are available to be used for patient testing. However, because of the time constraints of the surgical environment, it is feasible to include only a few tests in contrast to a clinical neuropsychological assessment that covers most domains. We have selected tests that target domains that are likely to change from pre- to post-operatively as shown in prior studies and those of our own. The CAM assessment was developed as a screening instrument based on operationalization of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) -III-R criteria for use by nonpsychiatric clinicians in high-risk settings. Based on a structured interview, the CAM algorithm consists of four clinical criteria: acute onset and fluctuating course, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. In order for delirium to be defined, both the first and second criteria have to be present, plus either criterion three or four. CAM has a sensitivity of 94–100% and a specificity of 90–95% and has a high inter-observer reliability 13 and has convergent agreement with four other mental status tests.

During the same interview of cognitive assessment by the research personnel, patients’ pain at rest was measured both pre- and post-operatively using an 11 point numerical rating scale in which 0 represents no pain and 10 represents worst imaginable pain.

Definition of Delirium

During the three interviews, trained interviewers determined the presence of delirium using the CAM. 13 All assessments of postoperative delirium were validated by a second investigator (LPS). We defined the occurrence of delirium as the patient meeting CAM criteria for delirium on either the first or second postoperative day assessments.

Assessment of Descriptive Characteristics and Covariates

The potential covariates included those shown in prior research to be associated with postoperative delirium. 10,14,15 The initial covariates analyzed are shown in table 1. Each of the covariate was collected either at the preoperative interviews or abstracted from medical records. Laboratory abnormalities were defined as any abnormalities involving serum sodium < 130 or > 150 mmol/L; potassium < 3 or > 6 mmol/L; or glucose < 60 or > 300 mg/dL.7 We also measured the potential association between preoperative hemoglogin level, serum creatinine level, and oxygen saturation level with the occurrence of postoperative delirium. Medical record review was conducted to obtain information on the type of surgery, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, 16 number and severity of preoperative comorbid conditions, and the type of anesthesia (general, regional or combined). Surgical risk was estimated using the guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association update for the perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery. 17 In addition, we evaluated the whether patients had a previous history of central nervous system (CNS) disorders which included a history of delirium, clinical diagnosis of dementia, a history of or current depression, history of seizure and other miscellaneous disorders such as Parkinson’s Disease.

Table 1.

Bivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Postoperative Delirium

| Variable | Delirium on postoperative day 1 or day 2

|

Test statistic[df, N] | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | No (N = 347) | N2 | Yes (N = 234) | |||

| Age (years), Mean ± SD | 347 | 72.8 ± 5.9 | 234 | 74.6 ± 6.3 | t[579,N=581] = 3.44 | .001 |

| Gender | 347 | 234 | χ2[1,N=581] = 21.48 | <.0001 | ||

| Female | 147 (50%) | 145 (50%) | ||||

| Male | 200 (69%) | 89 (31%) | ||||

| GDS scores | 335 | 216 | χ2[1,N=551] = 11.67 | .001 | ||

| < 6 | 298 (64%) | 169 (36%) | ||||

| ≥ 6 | 37 (44%) | 47 (56%) | ||||

| TICS scores | 333 | 212 | χ2M[1,N=545] = 24.16 | <.0001 | ||

| < 30 | 51 (44%) | 64 (56%) | ||||

| 30–35 | 164 (61%) | 106 (39%) | ||||

| ≥ 35 | 118 (74%) | 42 (26%) | ||||

| Number of dependency in 5 ADLs | 347 | 232 | χ2[1,N=579] = 10.06 | .002 | ||

| 0 | 305 (63%) | 181 (37%) | ||||

| ≥ 1 | 42 (45%) | 51 (55%) | ||||

| Number of dependency in 7 IADLs | 339 | 215 | χ2M[1,N=554] = 12.13 | .0005 | ||

| 0 | 242 (66%) | 126 (34%) | ||||

| 1 | 45 (59%) | 31 (41%) | ||||

| ≥ 2 | 52 (47%) | 58 (53%) | ||||

| History of CNS disorder | 344 | 232 | χ2[1,N=576] = 11.24 | .001 | ||

| Yes | 138 (52%) | 126 (48%) | ||||

| No | 206 (66%) | 106 (34%) | ||||

| Alcohol use | 337 | 229 | χ2M[1,N=566] =1.66 | .198 | ||

| None | 139 (55%) | 114 (45%) | ||||

| 1 drink | 169 (65%) | 92 (35%) | ||||

| ≥ 2 drinks | 29 (56%) | 23 (44%) | ||||

| Social support | 346 | 232 | Fisher P = 0.0001 | .007 | ||

| Home with partner | 264 (63%) | 156 (37%) | ||||

| Home alone | 78 (55%) | 65 (45%) | ||||

| Other | 4 (27%) | 11 (73%) | ||||

| Highest level of education | 334 | 227 | χ2[2,N=561] = 11.01 | .004 | ||

| High school graduate or lower | 68 (48%) | 74 (52%) | ||||

| College | 169 (65%) | 93 (35%) | ||||

| Post college | 97 (62%) | 60 (38%) | ||||

| Charlson Comorbidity index | 347 | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 234 | 1.5 ± 1.7 | t[579,N=581] = −0.43 | .668 |

| Surgical risk | 347 | 234 | χ2[1,N=581] = 3.97 | .046 | ||

| I–II | 286 (62%) | 177 (38%) | ||||

| III | 61 (52%) | 57 (48%) | ||||

| Type of anesthesia | 344 | 234 | χ2[1,N=578] = 0.17 | .679 | ||

| General I (1,2,3,7) | 240 (59%) | 167 (41%) | ||||

| Regional II I (4,5,6,8) | 104 (61%) | 67 (39%) | ||||

| Epidural Analgesia | 347 | 234 | χ2[1,N=581] = 3.29 | .070 | ||

| Yes | 59 (52%) | 54 (48%) | ||||

| No | 288 (62%) | 180 (38%) | ||||

| ASA classification | 347 | 234 | χ2[1,N=581] = 4.53 | .033 | ||

| I–II | 172 (64%) | 95 (36%) | ||||

| III–IV | 175 (56%) | 139 (44%) | ||||

| Surgery type | 347 | 234 | χ2[3,N=581] = 9.94 | .019 | ||

| Spine and major joints arthroplasty | 180 (54%) | 152 (46%) | ||||

| Urological and gynecological | 69 (66%) | 35 (34%) | ||||

| Vascular | 28 (70%) | 12 (30%) | ||||

| Other (General, thoracic, ENT, plastic) | 70 (67%) | 35 (33%) | ||||

| Use of preoperative opioids | 347 | 234 | χ2[1,N=581] = 3.53 | .060 | ||

| Yes | 92 (54%) | 79 (46%) | ||||

| No | 255 (62%) | 155 (38%) | ||||

| Preoperative rest pain score | 343 | 1.8 ± 2.6 | 233 | 2.5 ± 2.9 | t[574,N=576] = 3.26 | .001 |

| Laboratory abnormalities | 312 | 208 | Fisher P = 0.09 | .153 | ||

| Yes | 7 (88%) | 1 (13%) | ||||

| No | 305 (60%) | 207 (40%) | ||||

| Preoperative O2 Saturation Abnormality | 345 | 233 | χ2[1,N=578] = 0.02 | .880 | ||

| No | 109 (32%) | 75 (32%) | ||||

| Yes | 236 (68%) | 158 (68%) | ||||

| Preoperative Creatinine Level | 310 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 204 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | t[512,N=514] = 0.24 | .807 |

| Preoperative Hemoglobin | 323 | 13.2 ± 1.6 | 213 | 12.9 ± 1.6 | t[534,N=536] = 0.24 | .056 |

N1, N2 = Number of patients without and with is shown for each variable, respectively. GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; TICS = Telephone interview for Cognitive Status; ADL = Katz basic Activities of Daily Living Scale; IADL = Lawton-Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale; CNS = Central Nervous System; ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; NRS = Numeric Rating Scale of pain at rest (0 – 10).

χ2 = Chi-square test value. Fisher P= Fisher’s exact test table probability. χ2M = Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test value. t = Student t-test value

Analysis of pain and opioid dose

For analysis, pain level was dichotomized at ≥ 5, to reflect pain that was mild vs. more severe. 18 For each postoperative day when patients were being evaluated for cognitive status, opioid received during the 24-hour period was measured. Opioid dose was dichotomized at >8 mg (75th percentile for opioid use in our cohort) received in a 24 hour period after surgery, after converting morphine and fentanyl dose to hydromorphone dose using the formula: 5 mg of morphine sulfate = 1 mg of hydromorphone, 50 mcg of fentanyl = 1 mg of hydromorphone 19. If oral morphine was administered, the conversion was performed using 10mg IV morphine = 30mg PO morphine. 20

Statistical Analysis

To develop the prediction model for delirium, covariates that had been demonstrated in prior research to be associated with the presence of delirium were evaluated using χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, Mantel-Haenszel χ2 tests for ordinal variables, and Student t -tests for continuous variables. Only those covariates with associations with delirium of P-value ≤.20 were included in the prediction model. The model fit of the prediction model was assessed by computing Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and the C-statistic. To internally validate the prediction model, we executed the 10-fold cross-validation technique. 21 In 10-fold cross-validation, the original data set is randomly split into 10 sets. Each one-tenth of the data is treated as the validation set and the other nine-tenths are treated as the derivation set. 22 This is accomplished by randomly partitioning into 10 nearly equally sized sets, computing a logistic regression with the covariates in the final model using the derivation set and kept parameter estimates of the model and predictive scores from the validation set. This procedure was repeated 10 times. We then computed the area under the curve (AUC) for the predictive scores to assess the model validation.

To determine whether preoperative risk moderates the effect of postoperative pain and opioid dose on delirium, we evaluated the three-way interaction between preoperative risk and pain and opioid dose on postoperative delirium in a logistic regression. The model fit was assessed by Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. To improve interpretability of this interaction, we classified the cohort into dyadic risk groups according to subjects’ risk score for delirium. Pain and opioid dose are categorized as described above. We then computed odds ratio to describe the differing incidence of delirium for those at each preoperative risk of delirium for differing levels of pain and opioid dose. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3.

Results

Overall, 594 patients were included in the analysis. A subset of patients in this study (n=333) was included in a prior study that described the association between postoperative pain and pain management on the development of delirium. 10 That study did not consider postoperative opioid dose, or whether preoperative risk for delirium moderates the association between postoperative pain and opioid dose and incident delirium.

The mean age of the patients in the present study was 73.6 ± 6.1 years (range, 65–96 years): 31% of patients were 65–69 years old, 51% were 70–79 years old, and 18% were 80 years old or older. Approximately 50% of the patients were women. Overall, 13 patients had incomplete delirium data, leaving 581 in the analytic sample. The demographics of the patients with missing delirium data were similar to those with complete data. No patient had preoperative delirium. Forty percent of patients developed delirium on either the first or second postoperative days. Table 1 shows the bivariate association between baseline variables and delirium. Patients most likely to develop delirium were female, described more depressive symptoms, had lower TICS scores preoperatively, and reported more often to have dependency in activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), had a history of central nervous system disorders, and had lower mean preoperative hemoglobin level.1 Higher surgical risk and high numeric rating scale of preoperative rest pain were also associated with increased incidence of delirium.

Development of the Predictive Model

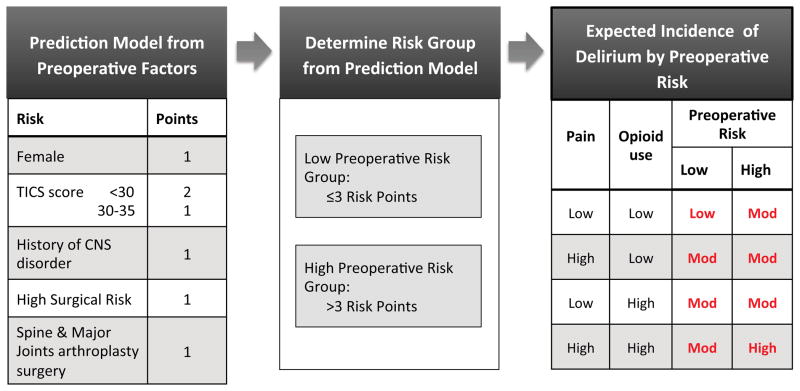

For development of the final predictive model, we analyzed the variables with bivariate association of P-value ≤ .20 in stepwise logistic regression. Table 2 summarizes the result of the stepwise logistic regression and 10-fold cross-validation. The final model revealed five risk factors: gender, a history of central nerve system disorder, preoperative TICs score, surgical risk, and surgery type. We developed a risk stratification system by assigning 1 point to each of the final risk factor present (figure 1) to derive the low risk (≤3 risk points), and high risk groups (>3 risk points).

Table 2.

Preoperative Predictors of Delirium in Final Model

| Effect | Label | Wald Chi-square

|

Maximum Likelihood

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | χ2 | P | Estimate | Standard Error | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||

| Gender | Female vs. Male | 1 | 9.51 | .002 | 0.59 | 0.19 | 1.81 (1.24–2.63) |

| Preoperative TICS score | <30 vs. ≥ 35 | 2 | 19.32 | <.0001 | 1.18 | 0.27 | 3.25 (1.90–5.54) |

| 30–35 vs. ≥ 35 | 0.71 | 0.23 | 2.03 (1.30–3.18) | ||||

| History of central nervous system disorder | Yes vs. No | 1 | 4.03 | .045 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 1.47 (1.01–2.13) |

| Surgical risk | III vs. I–II | 1 | 8.42 | .004 | 0.67 | 0.23 | 1.96 (1.24–3.08) |

| Surgery type | Orthopedic/Neurological vs. Other | 1 | 8.99 | .003 | 0.59 | 0.20 | 1.81 (1.23–2.66) |

TICS = telephone interview of cognitive status. N = 541.

Logistic regression was performed. The goodness of fit test of the final model was satisfied (P = .838) and C statistic of the prediction model is .687 (95% CI = .642–.733). Area under the curve by 10-fold cross-validation is .650.

Figure 1. The interaction of preoperative risk predictors and postoperative pain and opioids on postoperative delirium.

Low risk is defined when patients have 3 risk points or fewer and high risk with 4 or more risk points.

The risk points are defined by giving 1 point to each of the independent risk factors identified in the model where:

Female gender = 1 point

A history of central nerve system disorder = 1 point

Preoperative TICs score (<30 = 2 points, 30–35 = 1 point, and >35 = 0 point)

Surgical risk (high = 1 point, low or intermediate = 0 point)

Surgery type (orthopedic and spine surgery = 1 point, others = 0 point)

TICS = telephone interview of cognitive status, CNS = central nervous system, mod = moderate

See text for details.

Notably, the incidence of postoperative delirium was higher for those with greater preoperative risk (low risk 31% and high risk 51%). The relative risk of developing postoperative delirium for patients in high-risk group compared with those in low risk group was 2.38 {95% CI 1.67–3.40, χ2(df=1)=23.21, P < .0001}.

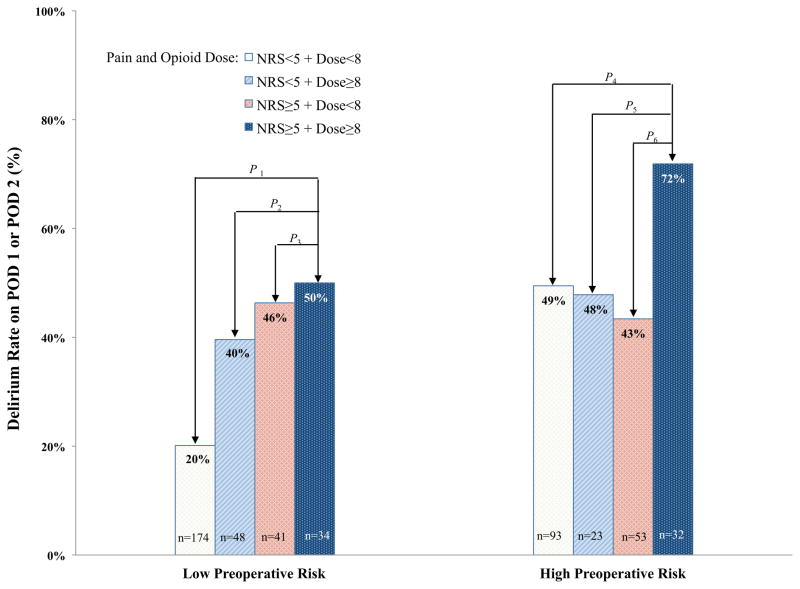

Incidence of Delirium by Preoperative Risk and Postoperative Pain and Opioid Dose

Next we performed a logistic regression with preoperative risk group, pain, and opioid dose and their interaction. The interaction between preoperative risk group and pain and opioid dose on the development of postoperative delirium was significant {χ2(df=1) = 5.49, P = .019}. The model fit statistic was acceptable (Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, P = 1.000). We next investigated the association between postoperative delirium and postoperative pain level and level of opioid dose separately for those at high vs. low preoperative risk for delirium (Figure 2). Within the low risk group, those with both high pain levels and receiving high dose opioid had an increased incidence of delirium vs. those with low pain and receiving low dose opioid {OR = 3.97, 95% CI = 1.84–8.56, χ2(df=1) = 12.40, P = .0004}. Similarly, comparison of other combinations of pain and opioid dose in the low risk group also had an increased incidence of delirium (low pain & high dose: OR=2.60, 95% CI=1.31–5.17, χ2(df=1) = 7.44, P = .006; high pain & low dose: {OR=3.43, 95% CI=1.67–7.03, χ2(df=1) = 11.35, P = .0008}. In the patients with low preoperative risk, we found that those with high postoperative pain or used high dose opioids had significantly higher incidence of delirium compared to those with low pain and used low opioid dose {OR = 3.28, 95% CI = 1.95–5.51, χ2(df=1) = 20.38, P < .0001}. Within the high risk group, those with both high pain levels and receiving high dose opioid had an increased incidence of delirium compared with those with low pain and receiving low dose opioid {OR = 2.61, 95% CI = 1.09–6.24, χ2(df=1) = 4.66, P = .031}, and also vs. those with high pain levels and receiving low dose opioid {OR = 3.33, 95% CI = 1.30–8.56, χ2(df=1) = 6.26, P = .012}. In addition, we found significantly higher delirium rate in the high pain and high opioid dose group compared to those with low pain or used low opioid dose {OR = 2.90, 95% CI = 1.24–6.76, χ2(df=1) = 6.03, P = .014} (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Delirium Rate by Preoperative Risk Group, Pain, and Opioid.

The incidence of postoperative delirium (%) is shown, stratified by whether the patients were in the low vs. high preoperative risk categories. A logistic regression was performed in each preoperative risk group. Comparisons were made on the effects of different combinations of pain status and opioid doses on incident delirium. The reference group for this comparison was patients with low pain and low opioid dose, within each risk category.

The test statistics and P-values are as follows:

P1: χ2(df=1) = 12.40, P = .0004. P2: χ2(df=1) = 0.87, P = .350. P3: χ2(df=1) = 0.10, P = .752. P4: χ2(df=1) = 4.66, P = .031. P5: χ2(df=1) = 3.20, P = .074. P6: χ2(df=1) = 6.26, P = .012.

POD = postoperative day, NRS = numerical rating scale of pain assessment

Discussion

In contrast to previous studies which focused on identification of predictors for postoperative delirium, our study assessed whether preoperative risk moderates the effect of postoperative pain and opioid dose on postoperative delirium. Significantly higher incidence of postoperative delirium was found among patients with one or more of the following preoperative risk factors: 1) preoperative cognitive impairment, 2) a history of central nervous system disorder, 3) a higher surgical risk level, 4) major spine or joint arthroplasty surgery, and 5) female. This approach allows us to understand how postoperative pain and opiate dose subsequently moderate the preoperative risk for postoperative delirium.

Comparison with previous studies

Numerous studies in the past have identified risk factors for delirium. Studies by Inouye et al., and Marcantonio et al. did not separate preoperative and perioperative factors. Furthermore, prior studies have not considered whether preoperative risk moderates the association between postoperative pain control and delirium. This novel approach provided evidence that some patients are more vulnerable to postoperative pain interventions. In older patients, it has been shown that baseline vulnerability can modify the impact of precipitating events on outcomes. 25 Our study uses the same conceptual framework that baseline vulnerability increases the effect of precipitating events such as the presence of high postoperative pain and opiate use on postoperative delirium.

In addition to the opioid effects on cognition as demonstrated in previous studies in healthy volunteers who received parenterally administered opioids, 26–29 under-treated pain may also be an alternative cause for postoperative delirium. 30 Our results expand upon earlier findings. We found that the effect of postoperative pain and opioid doses on incident delirium is not the same for all patients and that it differs depending upon preoperative risk for delirium. Our results show that high pain and/or high opioid dose increased risk for postoperative delirium in low risk patients. However, among high-risk patients, only the combination of both high pain and high opioid dose increase the incidence of delirium (shown in figure 1). It is possible that the vulnerability for developing delirium among patients with high preoperative risk is sufficiently high that the additive effect of only one postoperative risk (either high postoperative pain or high postoperative opioid doses) is not detectable. However, the combination of both high postoperative pain and opioid doses clearly increases risk for postoperative delirium among patients with high preoperative risk. In fact, nearly three of four patients who fit this profile experienced postoperative delirium. Taken together, data to date suggest that the interaction between pain and postoperative analgesia on delirium occurrence warrants further investigation.

Generalizability of results

The overall rate of delirium of 40% reported in our study is comparable to previous studies of older surgical patients undergoing major surgery. 2,11,31,32 Of note, even in the low risk group in our study, the delirium rate was 26%, suggesting that in patients aged ≥ 65 years and in the setting of major surgery, cognitive changes after surgery are common and should be a major focus of continued research.

In comparison to the prediction models described by Inouye et al, in general medical patients, and in the study by Marcantonio et al. in patients undergoing elective noncardiac surgery, the fit of both of these models was poor in our patient cohort when using predictors identified by these two studies. 23,24 The differences in results may be due to patient population and/or changing perioperative practice. For example, markedly abnormal preoperative sodium, potassium or glucose levels are rare in our patients awaiting elective surgery given the comprehensive preoperative patient evaluation and optimization by the perioperative providers at our institution.

Clinical implications

Our present results provide a novel way to risk-stratify patients based on preoperative risk and the associated effects of postoperative pain and opioids on postoperative delirium. Figure 1 shows how the incidence for postoperative delirium is increased based on preoperative risk predictors and moderating effects of the precipitating factors. Reducing the incidence of delirium may involve multimodal therapy including the use of adjuvant nonopioid analgesics 33 or regional techniques such as peripheral nerve blocks or epidural analgesia as adjuvant approach to optimize pain control by decreasing opioid use to ultimately minimizing the occurrence of postoperative delirium. Although intravenous opioids have been the mainstay of managing acute postoperative pain, our study suggests that for patients identified to be at high risk for postoperative delirium, a more innovative way of managing postoperative pain may include the complete avoidance of intravenous opioids if regional analgesia such as postoperative nerve blocks or epidural analgesia is feasible and indicated. Importantly, special attention should be given to the high-risk patients because their preoperative risk makes them particularly vulnerable for the development of postoperative delirium. Therefore, additional risk associated with postoperative pain and opiates use makes delirium an almost certain outcome in this group.

In fact, a recent study from Scandinavia in patients undergoing elective knee or hip arthroplasty showed that postoperative delirium was completely avoided when a multi-modal analgesic regimen was used with “minimal amount” of opioids 34 Clearly, results from this study will need further confirmation by future studies including the use of a proper control group. However, the results are suggestive that innovative postoperative pain therapy with opioid-sparing capability may lead to better cognitive outcomes.

Potential limitations

We focused on measuring delirium in the early postoperative period, as subjects in this investigation were included in a larger study examining perioperative management and delirium. As a result, incidents of later onset delirium may have been missed. Furthermore, these later onset cases may have different etiologies. Additionally, focusing on the early postoperative period may have accentuated the effects of acute surgical pain and opioids on postoperative delirium. Although we have described an association between postoperative opioids use, pain scores, and postoperative delirium, we cannot determine the mechanism as to how these factors interact to precipitate postoperative delirium. Future investigations are needed to determine the precise relationship.

We used the Confusion Assessment Method as a screening tool for delirium because of its documented high sensitivity and specificity when compared with the DSM criteria. However, without a psychiatrist’s diagnosis or the use of a more thorough standardized scale such as the Delirium Rating Scale, we can only conclude that the reported incidence of delirium was only based on a screen and not a from a formal diagnostic test.

The use of a subjective instrument in measuring pain such as the numerical rating scale may pose substantial limitation in subjects with perceptual disturbance such as postoperative delirium, as the validity of the assessment is uncertain. Although we previously demonstrated that patients who were delirious were equally consistent in their reports of resting pain evaluation than those who were not delirious, 9 future investigations to evaluate the validity of numerical rating scale in patients with postoperative delirium are clearly indicated given the assessment challenges in patients with cognitive impairment. 35

In addition, TICS is not sensitive to measuring mild cognitive impairment, 36 therefore, we were not able to determine the association between preoperative mild cognitive impairment and risk for delirium.

Finally, we used the 10 fold cross-validation to assess the accuracy of our final model. The lack of a separate external cohort for validation of the model is a potential limitation and the incorporation of which should be considered in future investigations.

Summary

In summary, in an elderly surgical cohort, we found that the highest incidence of delirium occurred in patients who had high preoperative risk for delirium, and also experienced high postoperative pain and used high opioid doses postoperatively. The effects of high levels of postoperative pain and/or using high postoperative opioid doses on the development of postoperative delirium differed for those at high versus low preoperative risks. Therefore, optimizing methods of postoperative pain control is an important clinical goal in older patients at risk for postoperative delirium, particularly in those identified to be at high preoperative risk.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by the National Institute of Aging, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, Grant # NIH 1RO1AG031795-04 (Leung).

Footnotes

Overall, 46% of patients were found to have a history of any previous CNS disorders which included delirium (20%), dementia (2%), depression (31%), current depression (14%), seizure (2%) and other CNS disorders (5%).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lipowski Z. Delirium (acute confusional states) JAMA. 1987;258:1789–1792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dasgupta M, Dumbrell AC. Preoperative risk assessment for delirium after noncardiac surgery: a systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006 Oct;54(10):1578–1589. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brauer C, Morrison RS, Silberzweig SB, Siu AL. The cause of delirium in patients with hip fracture. Archives of internal medicine. 2000 Jun 26;160(12):1856–1860. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inouye S, Charpentier P. Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons: predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA. 1996;275:852–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Litaker D, Locala J, Franco K, Bronson DL, Tannous Z. Preoperative risk factors for postoperative delirium. General hospital psychiatry. 2001 Mar-Apr;23(2):84–89. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudolph JL, Marcantonio ER. Review articles: postoperative delirium: acute change with long-term implications. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2011 May;112(5):1202–1211. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182147f6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcantonio E, Goldman L, Mangione C, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271:134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch E, Lazor M, Gellis J, Orav J, Goldman L, Marcantonio E. The impact of postoperative pain on the development of postoperative delirium. Anesthesia and analgesia. 1998;86:781–785. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199804000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung JM, Sands LP, Paul S, Joseph T, Kinjo S, Tsai T. Does postoperative delirium limit the use of patient-controlled analgesia in older surgical patients? Anesthesiology. 2009 Sep;111(3):625–631. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181acf7e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaurio L, Sands L, Wang Y, Mullen E, Leung J. Postoperative delirium: the importance of pain and pain management. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2006;102:1267–1273. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000199156.59226.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalisvaart KJ, Vreeswijk R, de Jonghe JF, van der Ploeg T, van Gool WA, Eikelenboom P. Risk factors and prediction of postoperative delirium in elderly hip-surgery patients: implementation and validation of a medical risk factor model. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006 May;54(5):817–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein M. The telephone interview for cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1988;1:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inouye S, van Dyke C, Alessi C, Balkin S, Siegal A, Horwitz R. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung J, Sands L, Mullen E, Wang Y, Vaurio L. Are preoperative depressive symptoms associated with postoperative delirium in geriatric surgical patients? J Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 2005;60A:1563–1568. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.12.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung JM, Sands LP, Vaurio LE, Wang Y. Nitrous oxide does not change the incidence of postoperative delirium or cognitive decline in elderly surgical patients. British journal of anaesthesia. 2006 Jun;96(6):754–760. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Society of Anesthesiologists. New classification of physical status. Anesthesiology. 1963;24:111. [Google Scholar]

- 17.ACC/AHA guideline update for the perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery - executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to update the 1996 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery) Anesthesia and analgesia. 2002;94:1052–1064. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zelman DC, Hoffman DL, Seifeldin R, Dukes EM. Development of a metric for a day of manageable pain control: derivation of pain severity cut-points for low back pain and osteoarthritis. Pain. 2003 Nov;106(1–2):35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gagliese L, Gauthier LR, Macpherson AK, Jovellanos M, Chan VW. Correlates of postoperative pain and intravenous patient-controlled analgesia use in younger and older surgical patients. Pain Med. 2008 Apr;9(3):299–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patanwala AE, Duby J, Waters D, Erstad BL. Opioid conversions in acute care. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2007 Feb;41(2):255–266. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohavi R. A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. San Mateo: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Refaeilzadeh P, Tang L, Liu H. Cross Validation. In: MÃz LL, editor. Encyclopedia of Database Systems. Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Jr, Baker DI, Leo-Summers L, Cooney LM., Jr The Hospital Elder Life Program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Hospital Elder Life Program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000 Dec;48(12):1697–1706. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcantonio E, Flacker J, Wright R, Resnick N. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. JAGS. 2001;49:516–522. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill TM, Williams CS, Tinetti ME. The combined effects of baseline vulnerability and acute hospital events on the development of functional dependence among community-living older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999 Jul;54(7):M377–383. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.7.m377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill JL, Zacny JP. Comparing the subjective, psychomotor, and physiological effects of intravenous hydromorphone and morphine in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology. 2000 Sep;152(1):31–39. doi: 10.1007/s002130000500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerr B, Hill H, Coda B, et al. Concentration-related effects of morphine on cognition and motor control in human subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 1991 Nov;5(3):157–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker DJ, Zacny JP. Subjective, psychomotor, and physiological effects of cumulative doses of opioid mu agonists in healthy volunteers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999 Jun;289(3):1454–1464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zacny JP, Lichtor JL, Thapar P, Coalson DW, Flemming D, Thompson WK. Comparing the subjective, psychomotor and physiological effects of intravenous butorphanol and morphine in healthy volunteers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994 Aug;270(2):579–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison RS, Magaziner J, Gilbert M, et al. Relationship between pain and opioid analgesics on the development of delirium following hip fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003 Jan;58(1):76–81. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bohner H, Hummel TC, Habel U, et al. Predicting delirium after vascular surgery: a model based on pre- and intraoperative data. Annals of surgery. 2003 Jul;238(1):149–156. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000077920.38307.5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson TN, Raeburn CD, Tran ZV, Angles EM, Brenner LA, Moss M. Postoperative delirium in the elderly: risk factors and outcomes. Annals of surgery. 2009 Jan;249(1):173–178. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818e4776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leung J, Sands L, Rico M, et al. Pilot clinical trial of gabapentin to decrease postoperative delirium in older surgical patients. Neurology. 2006;67:1–3. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000233831.87781.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krenk L, Rasmussen LS, Hansen TB, Bogo S, Soballe K, Kehlet H. Delirium after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. British journal of anaesthesia. 2012 Apr;108(4):607–611. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu DF, Herr K. Pain in dementia: recognition and treatment. Journal of gerontological nursing. 2012 Feb;38(2):8–13. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20120113-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Katula JA, et al. Telephone interview for cognitive status (TICS) screening for clinical trials of physical activity and cognitive training: the seniors health and activity research program pilot (SHARP-P) study. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2011 Feb;26(2):135–143. doi: 10.1002/gps.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]