Abstract

Herpesviruses establish lifelong latent infections in their hosts. Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) targets a population of bone marrow-derived myeloid lineage progenitor cells that serve as a reservoir for reactivation; however, the mechanisms by which latent CMV infection is maintained are unknown. To gain insights into mechanisms of maintenance and reactivation, we employed microarrays of ∼26,900 sequence-verified human cDNAs to assess global changes in cellular gene expression during experimental CMV latent infection of granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GM-Ps). This analysis revealed at least 29 host cell genes whose expression was increased and six whose expression was decreased during CMV latency. These changes in transcript levels appeared to be authentic, judging on the basis of further analysis of a subset by semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR. This study provides a comprehensive snapshot of changes in host cell gene expression that result from latent infection and suggest that CMV regulates genes that encode proteins involved in immunity and host defense, cell growth, signaling, and transcriptional regulation. The host genes whose expression we found altered are likely to contribute to an environment that sustains latent infection.

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a ubiquitous, species-specific herpesvirus that causes serious, sometimes life-threatening disease in congenitally infected neonates as well as in immunocompromised solid-organ and bone marrow allograft transplant recipients (40). One of the principle reasons why CMV is the cause of disease is that this virus reactivates from latency in immunocompromised hosts. Lifelong latent infection occurs in a small percentage of hematopoietic progenitor cells, in which the viral genome is maintained as an extrachromasomal plasmid (4) at between 2 and 13 genome copies per infected cell (56). Reactivation from latency occurs sporadically throughout life but is enhanced by immunosuppression and allograft rejection in transplant recipients, in whom virus replication reaches high levels and can be detected in the peripheral blood (PB) as well as in body fluids (40). Studies using purified CMV-infected cell populations from healthy donors or experimentally infected granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GM-Ps) have identified monocytes and their progenitors as prominent sites of latent infection (3, 24, 34, 60, 62). Maintenance of latency and reactivation are linked to the cellular differentiation state (54, 58, 59, 63). Although CMV resides in progenitors that may give rise to a range of different cell types, including myeloid progenitors and possibly more primitive cells, PB monocytes appear to maintain latent infection and activated macrophages support reactivation and active replication. Analyses have suggested that only limited transcription occurs from the viral genome during latency (2, 15, 24). The major immediate-early (MIE) region expresses CMV latency-associated transcripts (CLTs) (17, 23-25, 56, 67) in a small subset of latently infected GM-Ps as well as during natural infection. Antibodies to the proteins encoded by these transcripts are present in the sera of healthy blood donors as well as in those of transplant recipients (25, 27), suggesting that these proteins are expressed during natural infection. Despite the significance of the latent phase of infection to the success of this virus as a human pathogen and the availability of cellular systems for the study of infection, CMV latency remains poorly understood.

Large-scale analyses of host cell transcript levels during productive CMV infection of permissive human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) has concentrated on the initial phase (6, 75) and impact of virion components such as gB (53). When global changes were assessed through 48 h postinfection on microarrays representing 12,626 genes, over 1,400 (over 11%) of cellular genes showed alterations in levels (6) without any obvious differences between viral strains (75). Little is known about the impact of latent infection by CMV on host cell transcription. Studies examining a number of leukocyte surface markers have suggested little impact of latent infection (17). Recent work has suggested that CMV infection reduces cell surface major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) levels normally found on GM-Ps (57), although this was shown to occur at a posttranscriptional level. The presence of novel viral transcripts in latently infected GM-Ps suggests that virus-encoded gene products might alter cellular gene expression and confer a survival advantage on the infected cell.

Here we investigate global changes in the host cell transcriptome during experimental latent infection of primary human GM-Ps to gain insights into how this infection might alter these cells. Using cDNA microarrays, we identified a subset of host cell genes whose expression becomes significantly and reproducibly altered by infection. Many of these genes could be classified and grouped together under major functional headings, including immunity and host defense, cell growth, signaling, and transcriptional regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Unless otherwise stated, all enzymes and molecular biology reagents were from BRL (Invitrogen), all chemicals were from Sigma, and all tissue culture products were from CSL, Parkville, Victoria, Australia.

Cell and virus culture.

Primary human fetal liver-derived GM-Ps were grown in GM-P medium as previously described (24) except that cells were maintained at a concentration of 2 × 106/ml. On day 4 of culture growth, nonadherent cells were either mock infected or infected with CMV strain Toledo at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 3. Mock infection was performed in parallel with CMV infection and involved treating GM-Ps in the same way as those infected with CMV except for the omission of virus. GM-Ps for mock and CMV latent infection were prepared from the same fetal liver sample, and the cell numbers, volumes and concentrations, incubation times, medium batches, washes, and centrifugation steps were all kept constant. Nonadherent cells were transferred to fresh culture flasks three times per week. HFFs at passages 13 to 18 were used for virus propagation and plaque assays to determine virus titers. Assessment of Toledo-infected GM-P cultures by cell dilution-PCR and quantitative competitive PCR (56) revealed detection of the viral genome down to a dilution of two GM-P cells and that each cell harbored (on average) between two and eight viral genomes. These analyses are consistent with our previous demonstration that the GM-P model of latency reproducibly results in more than 90% of myeloid progenitor cells becoming infected with CMV (MOI = 3), with the viral genome sequestered within cell nuclei (24, 56).

Although they were previously shown to be nonpermissive to productive CMV infection (17, 24, 56), we sought to confirm by plaque assay that the GM-Ps used in these studies did not support productive replication. In parallel with our microarray analyses, on day 14 postinfection cell lysates (from 104 cells) and culture supernatants were grown in cultures with permissive HFFs for 10 days without any evidence of plaque formation. These data are consistent with previous reports of studies that failed to detect productive infection of GM-Ps even within the first week after exposure to virus (24, 56, 67).

RNA isolation and amplification.

Total RNA was extracted using an RNAqueous kit (Ambion Inc.). For microarray experiments, mRNA was amplified using a modification of a linear amplification method (64). Equal amounts of mock-infected and infected RNAs were reverse transcribed in the presence of 4 μg of T7 RNA polymerase promoter-containing oligo-dT primer (Genset)-0.6 M trehalose-1× First Strand buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2)-10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)-40 U of RNaseout-200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs)-5 ng of linear acrylamide/μl (Ambion, Inc.)-200 U of SuperScript II at 37°C for 5 min followed by 45°C for 5 min and then alternating between 60°C for 2 min and 55°C for 2 min. Double-stranded (ds) cDNA was then synthesized in the presence of 1× Second Strand buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.9), 90 mM KCl, 4.6 mM MgCl2, 150 nM β-nicotine adenine dinucleotide, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 200 μM dNTPs, 10 U of Escherichia coli DNA ligase, 40 U of E. coli DNA polymerase, 2 U of RNase H) for 2 h at 16°C. Following extraction with phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1), ds cDNA was precipitated from the aqueous layer, desalted, and used together with a MegaScript transcription kit (Ambion Inc.) to transcribe an antisense RNA (aRNA) probe.

RNA labeling, microarray hybridization, and data analysis.

Equal amounts of aRNA from mock and latent cultures were incubated for 2 h at 42°C in the presence of 6 μg of random primers-1× First Strand Buffer-10 mM DTT-dNTP mix (1 mM dATP, dGTP, and dCTP and 0.6 mM dTTP)-13.3 U of SuperScript II/μl-3 nM of either Cya3-dUTP or Cya5-dUTP (Perkin Elmer). To account for any variation in the incorporation of Cya3 and Cya5, the dye labels were swapped in half of the experiments. Labeled cDNAs were washed with Tris-EDTA buffer (10:1), mixed with 20 μg of Cot-1 human DNA-20 μg of poly(A)-RNA (Sigma)-20 μg of tRNA, and concentrated using Microcon YM-30 filters (Millipore) before being hybridized in the presence of 3.4× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)-0.3% sodium dodecyl sulfate to microarrays for 16 h at 65°C. Glass microscope microarrays bearing ∼26,900 PCR-amplified, sequence-verified human cDNA clones (Research Genetics) were obtained from the Stanford University Department of Microbiology and Immunology Microarray Consortium. Prior to hybridization, microarrays were postprocessed using a protocol published at the following website address: http://cmgm.stanford.edu/pbrown/protocols/3_post_process.html.

Following hybridization, microarrays were washed sequentially for 2 min in 2× SSC-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1× SSC, and 0.2× SSC and scanned using a GenePix 4000-series dual laser scanner (Axon Instruments, Union City, Calif.). An integrated software package (GenePix Pro version 3.0) was used to acquire data from each hybridized microarray. Each of the spots on an array was subjected to the following quality control criteria. (i) GenePix software-assisted flagging was used to exclude spots that were missing or irregular in shape, had high background levels, or were otherwise poorly resolved. (ii) Median-normalized pixel intensity for both Cya3 and Cya5 was used to exclude spots with an intensity level of <100. The expression of a clone was defined as up- or downregulated when the corresponding spot met the above criteria and had a ratio of Cya5/Cya3 or Cya3/Cya5 median pixel intensity above the background level of 2.0 or higher in at least four out of six replicate experiments. Each protocol used in the generation and analysis of mock- and latently infected cells was carefully examined and standardized between experiments to minimize the introduction of cellular gene expression changes unrelated to CMV latent infection. The Stanford Online Universal Resource for Clones and ESTs was used to search individual clones by their identification numbers (http://www.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/sourceSearch). Supplementary data can be found at http://www.wmi.usyd.edu.au/milinstitute/cytomegalovirus.htm. The presentation of microarray-related information was based upon the Minimal Information About a Microarray Experiment standard as proposed by the Microarray Gene Expression Database group (5).

Semiquantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed with 200 ng of random hexamers-1× First Strand buffer-10 mM DTT-1 mM dNTPs-40 U of Rnaseout-200 U of SuperScript II at 42°C for 1 h, and 2 U of RNaseH was added at 37°C for 20 min to remove RNA from RNA:DNA hybrids. Serial 1:3 dilutions of cDNA were subjected to PCR with intron-spanning, gene-specific primers in 1× Platinum PCR Supermix (Invitrogen), with an initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min and then 35 cycles of 94, 60, and 72°C (30 s each). Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) products, together with a DNA size ladder, were resolved by electrophoresis. Product specificity was also determined by direct sequencing of RT-PCR products. The 5′ to 3′ sequences of the forward and reverse primers were as follows: for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), CGAGATCCCTCCAAAATCAA (forward) and TGTGGTCATGAGTCCTTCCA (reverse); for colony-stimulating factor 3 receptor (CSF3R), AGACTGGGAGCAGAGCTTCA (forward) and CAGCGTATCTGCAGGGTGTA (reverse); for monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), GCCTCCAGCATGAAAGTCTC (forward) and TCAAGTCTTCGGAGTTTGGG (reverse); for cyclic-AMP response element binding protein 1 (CREB1), GGAGCTTGTACCACCGGTAA (forward) and TACGTCTCCAGAGGCAGCTT (reverse); for S100 beta neural, ATGTCTGAGCTGGAGAAGGC (forward) and GTAACCATGGCAACAAAGGC (reverse); for protein kinase R, CCGTCAGAAGCAGGGAGTAG (forward) and ATGCCAAACCTCTTGTCCAC (reverse); for acute myeloid leukemia-1B (AML1b), CCCTAGGGGATGTTCCAGAT (forward) and GTGAAGGCGCCTGGATAGT (reverse); for myeloperoxidase (MPO), TGGACTTAGGACCTTGCTGG (forward) and GTGAAGTCGAGGTCGTGGTC (reverse); for bactericidal permeability increasing protein 1, GTGGTCAGGATCTCCCAGAA (forward) and TGCCACCAGACCATAGTTGA (reverse); for azurocidin 1 (AZU1), TTTTCCATCAGCAGCATGAG (forward) and ACTCGGGTGAAGAAGTCAGG (reverse); for POU domain 2 transcription factor 2 (POU2F2), CTTCAGCCAGACGACCATTT (forward) and GCCCAGCATGATTCAAGAAG (reverse); and for lymphocyte antigen 6 complex locus E (LY6E), ATCTTCTTGCCAGTGCTGCT (forward) and CGCACTGAAATTGCACAGA (reverse).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Alteration of host cell gene expression during experimental latent infection of GM-P cells.

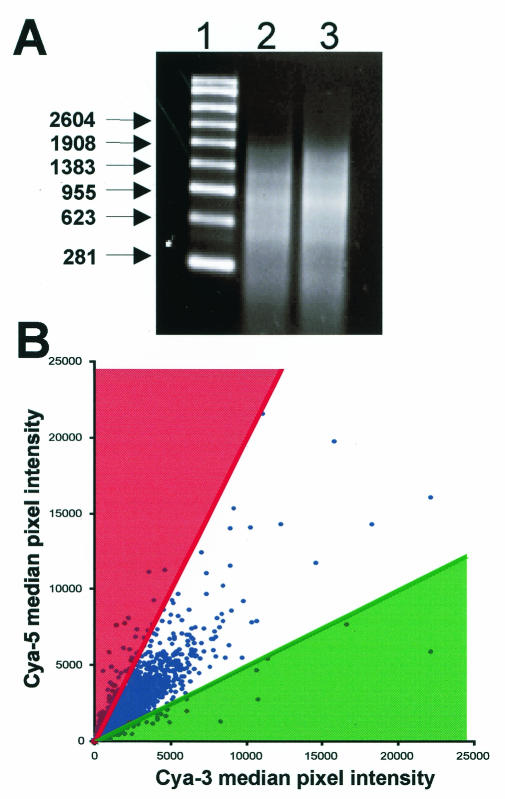

A microarray approach was applied to assess patterns of host cell gene expression in response to CMV latent infection. Latently infected cells were generated using a well-characterized cell culture-based system first described by Kondo et al. (24). GM-Ps were either mock infected or latently infected with CMV strain Toledo using an MOI = 3. On day 14 postinfection, total RNA was extracted and equal quantities (3 μg) were reverse transcribed using a primer consisting of poly(dT)-T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequences. Following ds cDNA synthesis, aRNA was generated by in vitro transcription. To confirm successful amplification, aliquots of denatured in vitro transcription products were electrophoresed in agarose gels and examined by ethidium bromide staining. The presence of a characteristic nucleic acid smear was consistent with the successful amplification of a large range of poly(A)-containing mRNAs (Fig. 1A). The majority of aRNAs ranged in size between ∼200 and ∼1,800 bp (as determined on the basis of comparison to molecular weight markers), with both mock- and latently infected samples being amplified to equal levels.

FIG. 1.

(A) Quality and size range of aRNAs. The mRNA from mock-infected or CMV latently infected cells was amplified using a linear amplification method. aRNAs from mock-infected (lane 2) and CMV latently infected (lane 3) cells were electrophoresed under denaturing conditions and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The size range of aRNAs was determined by comparison to a single-stranded RNA ladder (lane 1). The majority of aRNAs ranged in size from 200 to 1,800 bp. (B) Scatter plot depicting the median pixel intensities of Cya5 and Cya3 fluorescence on individual human cDNA clone spots after they were hybridized against aRNAs from mock-infected (Cya3-labeled) and latently infected (Cya5-labeled) GM-Ps. Upregulated (Cya5:Cya3 ≥ 2.0) and downregulated (Cya3:Cya5 ≥ 2.0) clones are shaded red and green, respectively. The vast majority of clones did not exhibit significantly altered expression (i.e., ratios ≤ 2.0). These are plotted between the colored trend lines.

aRNAs from mock-infected and infected cultures were labeled with either Cya3 or Cya5 fluorescent dyes and hybridized to cDNA microarrays bearing ∼26,900 human cDNA clone spots. These microarrays contained spots representing 7,642 unique human genes based upon known or suspected homology. The remainder were predominantly expressed sequence tags (ESTs) or clones without gene names (as determined by searching the Stanford Online Universal Resource for Clones and ESTs website). After each of the hybridized microarrays was scanned, an overlaid image of Cya3 and Cya5 fluorescence, together with a data set spreadsheet, was generated. Several quality controls were applied to ensure that only well-defined features with significant levels of hybridization were analyzed further (see Materials and Methods). A comparison of Cya3 and Cya5 median pixel intensity levels for each clone spot was generated as a scatter plot (Fig. 1B). When the data are displayed in this form, the clones that were up- or downregulated by a factor of at least 2.0 fall on or outside the trend lines indicated.

We performed six replicate experiments to identify host cell genes that were reproducibly altered during latent CMV infection. These six microarray experiments were performed using independent, freshly prepared GM-P cultures that were divided into two aliquots for mock or CMV latent infection. Each GM-P culture was derived from a separate fetal liver. Expression data were collated and compared across the six experiments. A number of statistical approaches for the designation of reproducibly altered genes have been proposed (38). We included in our list of significantly and reproducibly expressed clones those which met the quality control criteria for a “good” clone spot and whose expression levels were altered by a factor of 2.0 or more in at least four out of the six independent experiments. The use of a twofold cutoff value has been frequently used by others as a useful standard for selecting differentially expressed genes from microarray experiments (11, 19, 20, 45, 47, 65), and both theoretical and empirical calculations have supported the use of twofold changes as a robust and sometimes conservative cutoff value (49, 71, 72). This analysis of host cell gene expression during experimental latency in GM-Ps indicated that 60 clones were upregulated (mean severalfold upregulation, between 2.0 and 15.9) and that 8 were downregulated (mean severalfold downregulation, between 2.7 and 11.5). A total of 30 upregulated clones and 6 downregulated genes (representing about 0.5% of named genes) were named. These data revealed that CMV latent infection altered the expression of a subset of host cell genes (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of human cDNA clones upregulated or downregulated during latent CMV infection of GM-P cells

| Clone no. | Abbreviation(s) | LLIDa or accession no. | Clone name or characteristic(s) | Ratiob | SEMc | Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 759948 | S100B | 6285 | S100 beta (neural) | 15.9 | 4.6 | Up |

| 754479 | Clorf29 | 10964 | Chromosome 1 open reading frame 29 | 5.7 | 1.9 | Up |

| 148421 | NAd | BQ004606 | ESTs | 5.6 | 2.8 | Up |

| 289499 | NA | BM696564 | ESTs | 5.6 | 3.6 | Up |

| 784224 | FGFR4 | 2264 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 | 5.6 | 3.6 | Up |

| 285344 | NA | CA447283 | ESTs | 5.3 | 2.5 | Up |

| 205633 | CCL4 (MIP-1β) | 6351 | Small inducible cytokine A4 | 4.9 | 2.6 | Up |

| 284545 | NA | AK093907 | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ36588 fis, clone TRACH2013991 | 4.8 | 1.9 | Up |

| 360392 | MAP3K13 | 9175 | MAPK KK13 | 4.7 | 2.1 | Up |

| 592359 | HKE4 | 7922 | HLA class II region expressed gene KE4 | 4.7 | 2.0 | Up |

| 267634 | RAF1 | 5894 | v-raf-1, murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1 | 4.6 | 2.7 | Up |

| 1470048 | LY6E | 4061 | Lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus E | 4.5 | 1.7 | Up |

| 79576 | MS4A7 (Fc epsilon RI β7) | 58475 | Membrane-spanning 4-domains | 4.3 | 1.7 | Up |

| 561851 | NA | AK025205 | Homo sapiens cDNA: FLJ22547 fis | 4.1 | 2.0 | Up |

| 841238 | NA | AL713738 | Homo sapiens mRNA; cDNA DKFZp667P0610 | 4.0 | 1.7 | Up |

| 79726 | C17orf28 | 80791 | Chromosome 17 open reading frame 28 | 3.9 | 1.3 | Up |

| 199185 | MS4A7 (Fc epsilon RI β7) | 58475 | Membrane-spanning 4-domains | 3.9 | 0.8 | Up |

| 80109 | HLA-DQα | 3117 | MHC II, DQ alpha 1 | 3.7 | 0.8 | Up |

| 878259 | NA | AA775803 | EST, moderately similar to I68897 probable thioredoxin p | 3.7 | 1.6 | Up |

| 248528 | NA | N/A | In multiple clusters | 3.5 | 1.2 | Up |

| 303109 | P2Y5 | 10161 | Purinergic receptor (family A group 5) | 3.5 | 1.2 | Up |

| 504372 | NA | AK091799 | ESTs, moderately similar to hypothetical protein DKF | 3.5 | 1.0 | Up |

| 950587 | NA | AL713686 | Homo sapiens mRNA; cDNA DKFZp667B083 | 3.5 | 1.6 | Up |

| 23903 | NA | NA | In multiple clusters | 3.4 | 1.0 | Up |

| 395609 | NA | AW952334 | ESTs | 3.4 | 1.0 | Up |

| 840708 | NA | AK093984 | Homo sapiens, clone IMAGE:4711494, mRNA | 3.4 | 0.4 | Up |

| 23676 | NA | AK092850 | Homo sapiens clone 23676 mRNA sequence | 3.3 | 1.2 | Up |

| 160437 | CD169 | H22126 | Sialoadhesin | 3.2 | 0.7 | Up |

| 504302 | MGC16212 | 84855 | Hypothetical protein MGC16212 | 3.1 | 0.9 | Up |

| 725630 | PEA15 | 8682 | Phosphoprotein enriched in astrocytes 15 | 3.1 | 0.6 | Up |

| 258860 | NA | NA | In multiple clusters | 3.0 | 0.7 | Up |

| 813392 | RBM12 | 10137 | RNA binding motif protein 12 | 3.0 | 0.9 | Up |

| 898259 | NA | BM458572 | ESTs, weakly similar to hypothetical protein FLJ20378 | 3.0 | 0.9 | Up |

| 22374 | NA | NA | In multiple clusters | 2.9 | 0.9 | Up |

| 148444 | CREB1 | 1385 | cAMP-responsive element binding protein 1 | 2.9 | 0.7 | Up |

| 21567 | NA | AL832712 | Homo sapiens cDNA FLJ31019 fis | 2.8 | 0.9 | Up |

| 156962 | KIAA1145 | 57458 | KIAA1145 | 2.8 | 0.6 | Up |

| 239661 | SPK | 8189 | Symplekin; Huntingtin interacting protein I | 2.8 | 0.8 | Up |

| 323185 | PKR | BM462024 | Protein kinase R | 2.8 | 0.6 | Up |

| 810096 | SOX18 | 54345 | SRY (sex-determining region Y)-box 18 | 2.8 | 0.7 | Up |

| 50276 | KIAA1554 | 57674 | KIAA1554 protein | 2.7 | 0.5 | Up |

| 344139 | DOC1 | 11259 | Downregulated in ovarian cancer 1 | 2.7 | 0.9 | Up |

| 415535 | NA | W78782 | ESTs | 2.7 | 0.3 | Up |

| 487458 | CES1 | 1066 | Carboxylesterase 1 | 2.7 | 0.7 | Up |

| 769959 | COL4A2 | 1284 | Collagen, type IV, alpha 2 | 2.7 | 0.6 | Up |

| 504461 | OPN3 | 23596 | Opsin 3 (encephalopsin, panopsin) | 2.6 | 0.7 | Up |

| 589484 | RUNX1 | 861 | AML1 | 2.6 | 0.7 | Up |

| 525799 | GCHFR | 2644 | GTP cyclohydrolase I feedback regulatory protein | 2.5 | 0.5 | Up |

| 768561 | CCL2 (MCP-1) | 6347 | Monocyte chemotactic protein 1 | 2.5 | 0.5 | Up |

| 785699 | NA | AA449332 | EST | 2.5 | 0.6 | Up |

| 809533 | MGC14376 | 84981 | Hypothetical protein MGC14376 | 2.5 | 0.7 | Up |

| 288807 | BLAME | 56833 | B-cell activator macrophage expressed | 2.4 | 0.4 | Up |

| 487082 | SART2 | 29940 | Squamous cell carcinoma antigen recognized by T cell | 2.4 | 0.4 | Up |

| 809425 | MGC2654 | 79091 | Hypothetical protein MGC2654 | 2.4 | 0.3 | Up |

| 361323 | RGS1 | 5996 | Regulator of G-protein signaling 1 | 2.2 | 0.5 | Up |

| 504794 | RES4-22 | 8603 | Gene with multiple splice variants near HD locus | 2.2 | 0.4 | Up |

| 52076 | OLFM1 | 10439 | Olfactomedin 1 | 2.1 | 0.4 | Up |

| 742979 | NA | N/A | In multiple clusters | 2.1 | 0.4 | Up |

| 1358266 | POU2F2 | 5452 | POU domain, class 2, transcription factor 2 | 2.0 | 0.4 | Up |

| 436554 | MPO | 4353 | Myeloperoxidase | 11.5 | 4.9 | Down |

| 436741 | NA | AY044233 | Unknown (Homo sapiens), mRNA sequence | 7.9 | 3.0 | Down |

| 869466 | BPI | 671 | Bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein | 4.1 | 1.3 | Down |

| 448032 | AZU1 | 566 | Azurocidin 1 (cationic antimicrobial protein 37) | 4.0 | 1.7 | Down |

| 125308 | MPO | 4353 | Myeloperoxidase | 3.2 | 0.9 | Down |

| 298268 | BTG1 | 694 | B-cell translocation gene 1, antiproliferative | 3.0 | 0.6 | Down |

| 562729 | S100A8 | 6279 | S100 calcium binding protein A8 (calgranulin A) | 2.9 | 0.7 | Down |

| 809639 | CSF3R | 1441 | Colony-stimulating factor 3 receptor (granulocyte) | 2.7 | 0.8 | Down |

LocusLink identification number. In cases in which a clone did not have a LLID (as of 1/18/2003), its accession number is listed.

Mean severalfold ratio change.

Standard error of the mean severalfold ratio change.

NA, not applicable.

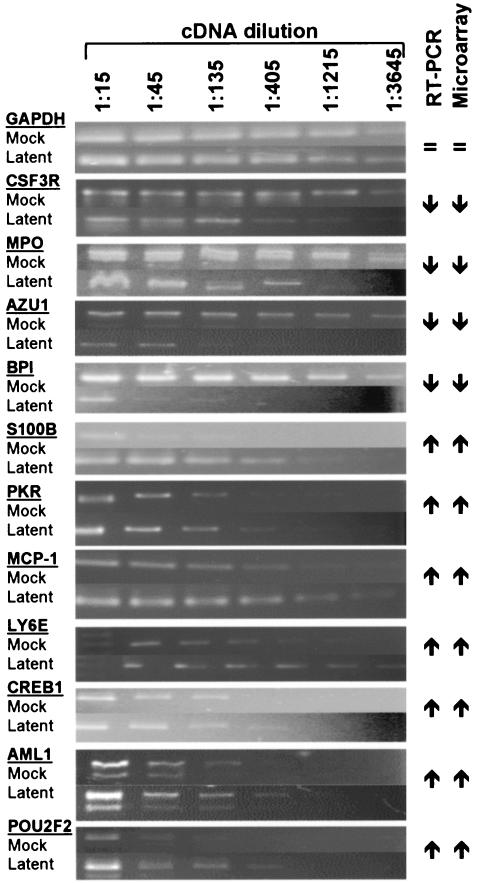

Validation of microarray data by semiquantitative RT-PCR.

To verify the microarray data, we performed RT-PCR on a subset of 11 randomly chosen genes which represented 7 of the upregulated and 4 of the downregulated genes. RNA from additional mock- or latently infected GM-Ps was reverse transcribed and serially diluted before amplification with gene-specific primers. RT-PCR of a putative housekeeping gene, GAPDH, was included for comparison. The dilution series of RT-PCR products from mock-infected and latently infected RNA samples were resolved by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2). All products migrated at their predicted sizes; in all cases, the dilution RT-PCR indicated either an up- or downregulation of transcription which correlated with the up- or downregulation indicated by the microarray data. In addition, the specificity of the assay was confirmed by direct sequencing of RT-PCR products. GAPDH was equally amplified from both the mock- and latently infected RNA samples, and this was consistent with microarray-derived data that showed no significant change in GAPDH expression during latent infection. The application of semiquantitative dilution RT-PCR served as an independent assessment of host cell gene transcription and validated the microarray assay. There is considerable published literature reporting a lack of correlation between microarray-based severalfold changes and PCR-based methods. For example, an examination of several studies which present both quantitative RT-PCR and microarray data suggest that, at best, quantitative RT-PCR will consistently reflect the up- and downregulated status and will not accurately reflect the magnitude of the severalfold changes as indicated by microarray (13, 44, 45). It is also interesting that microarrays have been frequently reported to underestimate the severalfold change with respect to absolute changes in transcript levels (13, 38, 46, 61, 68, 73).

FIG. 2.

Validation of microarray data with semiquantitative dilution RT-PCR. Serial threefold dilutions (from 1:15 to 1:3,645) of cDNA derived from mock-infected and latently infected GM-P cultures were amplified using gene-specific primers under limiting PCR cycle conditions. RT-PCR products were then separated by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. In total, transcripts from 1 housekeeping gene (GAPDH) and 11 other cellular genes were assessed for their relative abundances in mock-infected and latently infected GM-Ps; these data were compared with microarray-derived expression data for the same genes. GAPDH expression was unchanged (=). Upward- and downward-pointing arrows indicate up- and downregulation (as determined by dilution RT-PCR or microarray). In each case, dilution RT-PCR and microarray-derived data were consistent with each other.

Although the human cDNA clones used to generate microarrays used in our studies were from a sequence-verified set, we returned to the original microtiter clone storage plates that were used for microarray printing and sequenced a number of clones representing named genes that were consistently up- or downregulated during latent infection. We selected the 25 genes whose expression profiles had not been independently confirmed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Sequences were compared to the human genome sequence using the National Center for Biotechnology Information Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). Using this approach, 21 out of 22 successfully sequenced clones were verified as corresponding to the published sequence, with the clone that was not verified being omitted from the data set depicted in Table 1.

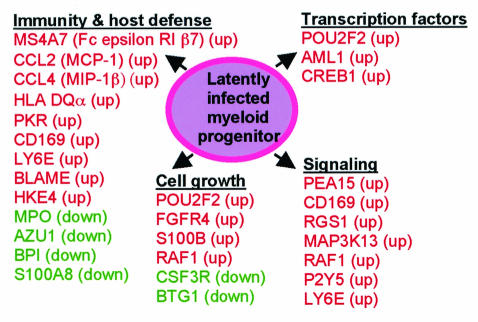

Functions of CMV-regulated host genes.

This study represents an initial global assessment of host cell gene transcriptional changes during latent CMV infection. Although the frequency with which protein levels equate to transcript levels measured by microarrays remains unclear, an assumption in the analysis of microarray-based studies that assess changes in transcription is that in many cases, these changes will at least reflect qualitative changes in protein expression of the corresponding gene. There are certainly likely to be exceptions to this assumption, so functional studies at the protein level will ultimately be required to determine the biological significance of these changes. This will be a major focus of our follow-up studies. Changes would also be best confirmed using latently infected cells isolated from naturally infected donors, but the lack of methods for identification and isolation of infected progenitor cells prevents such studies from being undertaken. Nevertheless, the importance of proceeding with studies using the GM-P model of latency is reinforced by previous findings using this model which have subsequently been validated in naturally infected individuals (17, 24, 25, 27, 56). Most of the named genes whose expression changed during latency could be categorized into functional groups that included transcription factors, immunity and host cell defense proteins, signaling, and cell growth functions (Fig. 3). On the one hand, these alterations may reflect the consequences of viral manipulation of host genes, presumably via the expression of viral gene products that aid latency or reactivation. On the other hand, changes may indicate the induction of host cell defense mechanisms aimed at limiting the consequences of latent infection. The ability of latent virus to persist in the host argues in favor of the former being true. Although the contribution of these gene expression changes to CMV latent infection remains speculative, many of these genes have known functions that are consistent with a supportive role during latency.

FIG. 3.

Diagram depicting a snapshot of CMV latency with respect to upregulated (red) and downregulated (green) genes which could be grouped by a related function(s). The majority of identified genes could be grouped under the following headings: transcription factors, immunity and host cell defense, signaling, and cell growth.

Most notably, transcription factors were upregulated during latent CMV infection that could impact productive immediate-early (IE) gene expression as well as latent gene expression. POU2F2 is a transcription factor that is differentially spliced to generate several isoforms. These isoforms play important roles as either repressors or activators of transcription of central nervous and immune system genes bearing the octamer motif ATTTGCAT, and POU family members have been shown to be involved in herpesvirus gene regulation (29). The microarrays used in our study were printed with a clone of POU2F2 whose sequence overlaps five POU2F2 isoforms due to the presence of at least one common exon. Dilution RT-PCR of RNA extracted from mock-infected and infected GM-Ps confirmed the upregulation of POU2F2 (Fig. 2), and sequence analysis of the RT-PCR product revealed the upregulation of isoform POU2F2.1. The function of this isoform appears to be cell type specific, as it can act as an activator in B cells but as a repressor in neuronal cells (29, 41). Our finding that this gene was upregulated in latency suggests a possible role as a repressor of productive CMV gene expression. In this respect, POU2F2 has been shown to repress the expression of both herpes simplex virus type 1 IE genes and a varicella zoster virus (VZV) IE gene (30, 41). Thus, as is suspected with respect to herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella zoster virus, POU2F2 may promote the shutdown of productive CMV infection and establishment of latency. Upregulation of POU2F2 in infected cells may sustain latent infection.

The transcription factor AML1, which is important in myeloid cell differentiation and oncogenesis (32), was also upregulated in latently infected GM-Ps. Differential splicing of AML1 mRNA gives rise to at least 11 isoforms that act as repressors and/or activators of transcription, depending on the cofactors that are recruited and the promoter context (21, 32). The microarrays we used contained an almost-full-length cDNA clone of isoform AML1b that has been shown capable of repression and activation (32). This clone shares homology with many other AML1 isoforms due to the presence of common exons. Direct analysis by RT-PCR with AML1b primers confirmed the upregulation of this isoform in latently infected GM-Ps. Although not yet as fully characterized, AML1b can mediate transcriptional repression by recruiting histone deacetylases (HDACs) and other factors to modify chromatin and control transcription (32). HDACs have been implicated in the regulation of latency of other herpesviruses, including Epstein Barr virus and human herpesvirus 8 (7, 16). In addition, a recent study by Murphy et al. (37) suggested that HDACs mediate repression of the CMV MIE promoter (MIEP) in nonpermissive cells because inhibition of HDACs induced viral permissiveness and increased MIEP activity. Thus, like that of POU2F2, upregulation of AML1b during CMV latent infection may also maintain latency by repressing IE gene expression. In addition, AML1b and the related gene AML1c (35) have been shown to be downregulated during productive CMV infection of permissive fibroblasts (6, 75), which is consistent with a role for this protein in repressing productive CMV gene expression. The cloning and subsequent transfection of primary human fibroblasts with constructs overexpressing isoforms of POU2F2 or AML1 will enable a direct assessment of the impact of these transcription factors on productive CMV gene expression.

CREB1 is a transcriptional activator whose transcript was upregulated during CMV latency. The importance of CREB1 to CMV infection is illustrated by the presence of multiple binding sites in the MIEP region, with at least one required for successful MIEP activity (33, 36, 66), as well as by the previously described interaction between CREB1 and the CMV IE2-p86 IE protein (28, 51). Given that the two transcriptional start sites for CMV sense CLTs are within the MIEP region (25), it is possible that some of these CREB1 binding sites mediate sense CLT expression. Interestingly, a binding site for this transcription factor is also located near the start site for the antisense CLTs, suggesting a possible role for CREB1 in modulating both classes of CLTs.

Latent CMV infection upregulated transcripts from the chemokine genes MCP-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP-1β). These are both CC chemokines that can mediate inflammation by attracting monocytes and macrophages, memory T cells, NK cells, hematopoietic progenitors, and possibly dendritic cells (9, 48). Consistent with the upregulation of these chemokines, follow-up experiments using a transwell chamber chemotaxis assay found a significant enhancement of monocyte chemotactic activity in response to CMV latent infection. In two replicate experiments using GM-Ps derived from two different liver samples, we observed a 1.8-fold and a 2.8-fold increase in monocyte migration when supernatant from latently infected GM-Ps was compared to supernatant from the corresponding mock-infected GM-Ps. Specific antibody blocking of MCP-1 and MIP-1β activity will help to define the roles of these chemokines in this increased monocyte chemotaxis. We found that the transcript for Fc epsilon R1 was also upregulated. This gene product induces the expression of CC chemokines, including MCP-1 and MIP-1β, in mast cells and monocytes (26, 39). Increased CC chemokine levels would potentially have a paracrine effect on other monocytes or reduce migration of the latently infected cells by an autocrine effect. Murine CMV encodes a CC chemokine homologue (MCK-2) that increases the inflammatory response at initial sites of infection during productive infection, resulting in a more efficient virus dissemination (50). In addition, human CMV UL146 is a CXC chemokine (vCXC-1) that attracts neutrophils and other CXCR2-bearing cells, presumably also to aid virus spread (42). The role of upregulated chemokine expression during latent CMV infection remains to be defined, but (in the context of the infected host) CMV-induced MCP-1 and MIP-1β may act to recruit leukocytes to sites of latent infection in a manner that could enable CMV to spread more efficiently to these cells. This could be particularly advantageous during the initial stages of reactivation from latency.

MPO is a host defense protein that mediates the production of potent oxidants and microbicidal agents. MPO has been shown to inactivate influenza virus (70) and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (22). It has also been shown to almost completely abolish infectivity of CMV in HFFs and significantly reduce the formation of both early and late CMV antigens in a monocyte cell line (THP-1) rendered permissive to productive infection by differentiation with the phorbol ester tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate (12). The mechanism of action of MPO against CMV is unknown, but this enzyme disrupts influenza virus envelope proteins (70). The downregulation of MPO expression during latent CMV infection may therefore provide conditions within the host cell that would minimize exposure of newly assembled virions to deleterious cellular defenses during reactivation.

CD169 has been shown to bind a range of leukocytes and is likely to be involved in macrophage-hemopoietic cell interactions (18). The upregulation of CD169 may facilitate adhesion of latently infected cells to other cells, potentially increasing residence of latently infected cells in bone marrow or other tissues or potentially increasing the efficiency of virus spread to permissive (e.g., dendritic) as well as to other nonpermissive (myeloid progenitor) cells during episodes of reactivation. CD169 is highly expressed on differentiated macrophages that appear at sites of inflammation. CMV reactivation is associated with inflammatory processes. Expression of CD169 may also accelerate disease processes.

Although our previous work demonstrated a downregulation of cell surface MHC-II protein expression during latent CMV infection (57), the present study showed that MHC-II transcript levels were increased. There are, however, a number of explanations that account for this apparent discrepancy. First, our previous publication reported a downregulation of cell surface MHC-II proteins. In contrast, our present microarray analysis reports the upregulation of the transcript encoding a MHC-II component (the HLA-DQ α chain). Successful expression of MHC-II on the cell surface is a multistep process which involves several posttranslational steps, including the binding of α and β chains, the processing and loading of an antigenic peptide, and the transport of the mature complex to the cell surface (43). Thus, downregulation of cell surface MHC-II may result from a defect in one of many steps in the assembly pathway. Downregulation at the cell surface does not necessarily mean that all components of the mature MHC-II complex are downregulated. In this respect, in our previous study cell surface MHC-II was downregulated but total cellular α chain was not (57). This clearly shows the dissociation between the latent CMV-based regulation of mature, cell surface-expressed MHC-II and its regulation of α chain synthesis.

Second, our previous publication reporting downregulation of cell surface MHC-II during latent CMV infection of hematopoietic progenitors used an HLA-DR-specific antibody (TU36) and therefore did not measure HLA-DQ expression. This is particularly important, because a discoordinated pattern of expression of the cell surface HLA-DR, -DP, and -DQ antigens has been frequently reported for normal tissues from biopsies or primary cultures, established cell lines, or tumor cells (1). Of most relevance here is the discoordinated expression of cell surface DR and DQ that has been reported with respect to hematopoietic progenitors (31, 52). Thus, it is probable that HLA-DR and HLA-DQ are not coordinately regulated in the hematopoietic progenitors used in our studies of CMV latency. For these reasons, a direct comparison cannot be made between the downregulation of cell surface-expressed HLA-DR protein complexes and the upregulation of HLA-DQ α chain transcription. An alternative reason to those presented above is that latently infected cells might increase HLA-DQ transcript levels in an attempt to compensate for CMV-mediated downregulation of cell surface HLA-DR proteins. In this respect, evidence for compensation mechanisms has been previously reported; one such example is the observation of cell surface DQ antigens on a DR-defective clone originating from the mutagenesis of the class II transactivator gene (CIITA) in an MHC-II-positive Burkitt lymphoma cell line (10, 74).

Phosphoprotein enriched in astrocytes 15 (PEA15) is a signaling protein expressed in most tissues that contains a death effector domain which binds to the death effector domain of caspase-8 (FLICE) and the intracellular adapter FADD. Through these interactions, PEA15 inhibits apoptosis signaling induced by tumor necrosis factor alpha and FasL (8). PEA15 also inhibits TRAIL-induced apoptosis analogous to c-FLIP via interaction with FADD (69) and so may prevent CMV-infected cells from falling victim to death receptor-mediated apoptosis. During productive infection, two CMV IE genes have been shown to encode potent antiapoptotic functions that impede such cell death. The UL36 gene encodes a viral inhibitor of caspase-8 activation (vICA) that binds and inhibits pro-caspase-8 and thus Fas-mediated apoptosis (55), and the UL37 exon 1 gene encodes a mitochondrion-localized inhibitor of apoptosis (vMIA) that blocks the release of cytochrome c during Fas-mediated apoptosis (14). Our detection of upregulated PEA15 expression during latency suggests that latent CMV might have induced a cellular antiapoptotic gene product to promote survival of the host cell.

This study identified a small, unique subset of cellular mRNAs whose expression becomes altered by CMV latent infection. Many of these mRNAs shared a related type of function within a few physiological areas, suggesting that the impact of latent virus on the host cell is quite restricted. Nonetheless, many of the differentially expressed genes encode functions that may confer a survival advantage to the virus during latency or the initial steps of virus reactivation; direct assessment of the biological impact of these gene expression changes will further define their roles in CMV pathogenesis. The viral gene products that mediate changes in the host cell transcriptome and the mechanisms involved in these changes are yet to be defined, but the presently identified open reading frames expressed during latency serve as ideal candidates for the assessment of their impact on the host cell. Correlating functionally important changes in host cell gene expression with the expression of viral genes during latency may ultimately lead to the identification of targets for the design of gene therapies to help reduce the clinical consequences of latency and reactivation during immunosuppression.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank Laura Hertel for her considerable efforts in generating and supplying cDNA microarrays and Mario Malkoun, Natalie Gava, and Lucy Webster for assistance with microarray experiments.

This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) Project grant 153873 (to B.S.) and USPHS grant RO1 AI33852 (to E.S.M.). A.A. and B.S. were holders of University of Sydney Rolf Edgar Lake Fellowships.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alcaide-Loridan, C., A. M. Lennon, M. R. Bono, R. Barbouche, K. Dellagi, and M. Fellous. 1999. Differential expression of MHC class II isotype chains. Microbes Infect. 1:929-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beisser, P. S., L. Laurent, J. L. Virelizier, and S. Michelson. 2001. Human cytomegalovirus chemokine receptor gene US28 is transcribed in latently infected THP-1 monocytes. J. Virol. 75:5949-5957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bevan, I. S., M. R. Walker, and R. A. Daw. 1993. Detection of human cytomegalovirus DNA in peripheral blood leukocytes by the polymerase chain reaction. Transfusion 33:783-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolovan-Fritts, C. A., E. S. Mocarski, and J. A. Wiedeman. 1999. Peripheral blood CD14+ cells from healthy subjects carry a circular conformation of latent cytomegalovirus genome. Blood 93:394-398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brazma, A., P. Hingamp, J. Quackenbush, G. Sherlock, P. Spellman, C. Stoeckert, J. Aach, W. Ansorge, C. A. Ball, H. C. Causton, T. Gaasterland, P. Glenisson, F. C. Holstege, I. F. Kim, V. Markowitz, J. C. Matese, H. Parkinson, A. Robinson, U. Sarkans, S. Schulze-Kremer, J. Stewart, R. Taylor, J. Vilo, and M. Vingron. 2001. Minimum information about a microarray experiment (MIAME)-toward standards for microarray data. Nat. Genet. 29:365-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Browne, E. P., B. Wing, D. Coleman, and T. Shenk. 2001. Altered cellular mRNA levels in human cytomegalovirus-infected fibroblasts: viral block to the accumulation of antiviral mRNAs. J. Virol. 75:12319-12330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant, H., and P. J. Farrell. 2002. Signal transduction and transcription factor modification during reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus from latency. J. Virol. 76:10290-10298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Condorelli, G., A. Trencia, G. Vigliotta, A. Perfetti, U. Goglia, A. Cassese, A. M. Musti, C. Miele, S. Santopietro, P. Formisano, and F. Beguinot. 2002. Multiple members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase family are necessary for PED/PEA-15 anti-apoptotic function. J. Biol. Chem. 277:11013-11018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conti, P., and M. DiGioacchino. 2001. MCP-1 and RANTES are mediators of acute and chronic inflammation. Allerg. Asthma Proc. 22:133-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douhan, J., R. Lieberson, J. H. Knoll, H. Zhou, and L. H. Glimcher. 1997. An isotype-specific activator of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II genes that is independent of class II transactivator. J. Exp. Med. 185:1885-1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisen, M. B., and P. O. Brown. 1999. DNA arrays for analysis of gene expression. Methods Enzymol. 303:179-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Messaoudi, K., A. M. Verheyden, L. Thiry, S. Fourez, N. Tasiaux, A. Bollen, and N. Moguilevsky. 2002. Human recombinant myeloperoxidase antiviral activity on cytomegalovirus. J. Med. Virol. 66:218-223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldman, A. L., N. G. Costouros, E. Wang, M. Qian, F. M. Marincola, H. R. Alexander, and S. K. Libutti. 2002. Advantages of mRNA amplification for microarray analysis. BioTechniques 33:906-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldmacher, V. S., L. M. Bartle, A. Skaletskaya, C. A. Dionne, N. L. Kedersha, C. A. Vater, J. W. Han, R. J. Lutz, S. Watanabe, E. D. Cahir McFarland, E. D. Kieff, E. S. Mocarski, and T. Chittenden. 1999. A cytomegalovirus-encoded mitochondria-localized inhibitor of apoptosis structurally unrelated to Bcl-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12536-12541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodrum, F. D., C. T. Jordan, K. High, and T. Shenk. 2002. Human cytomegalovirus gene expression during infection of primary hematopoietic progenitor cells: a model for latency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:16255-16260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gwack, Y., H. Byun, S. Hwang, C. Lim, and J. Choe. 2001. CREB-binding protein and histone deacetylase regulate the transcriptional activity of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus open reading frame 50. J. Virol. 75:1909-1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hahn, G., R. Jores, and E. S. Mocarski. 1998. Cytomegalovirus remains latent in a common precursor of dendritic and myeloid cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3937-3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartnell, A., J. Steel, H. Turley, M. Jones, D. G. Jackson, and P. R. Crocker. 2001. Characterization of human sialoadhesin, a sialic acid binding receptor expressed by resident and inflammatory macrophage populations. Blood 97:288-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iyer, V. R., M. B. Eisen, D. T. Ross, G. Schuler, T. Moore, J. C. Lee, J. M. Trent, L. M. Staudt, J. Hudson, Jr., M. S. Boguski, D. Lashkari, D. Shalon, D. Botstein, and P. O. Brown. 1999. The transcriptional program in the response of human fibroblasts to serum. Science 283:83-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izmailova, E. B. F., Q. Huang, N. Makori, C. J. Miller, R. A. Young, and A. Aldovini. 2003. HIV-1 Tat reprograms immature dendritic cells to express chemoattractants for activated T cells and macrophages. Nat. Med. 9:191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Javed, A., G. L. Barnes, B. O. Jasanya, J. L. Stein, L. Gerstenfeld, J. B. Lian, and G. S. Stein. 2001. runt homology domain transcription factors (Runx, Cbfa, and AML) mediate repression of the bone sialoprotein promoter: evidence for promoter context-dependent activity of Cbfa proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:2891-2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klebanoff, S. J., and F. Kazazi. 1995. Inactivation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by the amine oxidase-peroxidase system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2054-2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kondo, K., and E. S. Mocarski. 1995. Cytomegalovirus latency and latency-specific transcription in hematopoietic progenitors. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. Suppl. 99:63-67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kondo, K., H. Kaneshima, and E. S. Mocarski. 1994. Human cytomegalovirus latent infection of granulocyte-macrophage progenitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:11879-11883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kondo, K., J. Xu, and E. S. Mocarski. 1996. Human cytomegalovirus latent gene expression in granulocyte-macrophage progenitors in culture and in seropositive individuals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11137-11142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraft, S., N. Novak, N. Katoh, T. Bieber, and R. A. Rupec. 2002. Aggregation of the high-affinity IgE receptor FcεRI on human monocytes and dendritic cells induces NF-κB activation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 118:830-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landini, M. P., T. Lazzarotto, J. Xu, A. P. Geballe, and E. S. Mocarski. 2000. Humoral immune response to proteins of human cytomegalovirus latency-associated transcripts. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 6:100-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lang, D., S. Gebert, H. Arlt, and T. Stamminger. 1995. Functional interaction between the human cytomegalovirus 86-kilodalton IE2 protein and the cellular transcription factor CREB. J. Virol. 69:6030-6037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Latchman, D. S. 1996. Activation and repression of gene expression by POU family transcription factors. Philos. Transact. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 351:511-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lillycrop, K. A., C. L. Dent, S. C. Wheatley, M. N. Beech, N. N. Ninkina, J. N. Wood, and D. S. Latchman. 1991. The octamer-binding protein Oct-2 represses HSV immediate-early genes in cell lines derived from latently infectable sensory neurons. Neuron 7:381-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linch, D. C., L. M. Nadler, E. A. Luther, and J. M. Lipton. 1984. Discordant expression of human Ia-like antigens on hematopoietic progenitor cells. J. Immunol. 132:2324-2329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lutterbach, B., and S. W. Hiebert. 2000. Role of the transcription factor AML-1 in acute leukemia and hematopoietic differentiation. Gene 245:223-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meier, J. L., and M. F. Stinski. 1996. Regulation of human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene expression. Intervirology 39:331-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendelson, M., S. Monard, P. Sissons, and J. Sinclair. 1996. Detection of endogenous human cytomegalovirus in CD34+ bone marrow progenitors. J. Gen. Virol. 77:3099-3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyoshi, H., M. Ohira, K. Shimizu, K. Mitani, H. Hirai, T. Imai, K. Yokoyama, E. Soeda, and M. Ohki. 1995. Alternative splicing and genomic structure of the AML1 gene involved in acute myeloid leukemia. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:2762-2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mocarski, E. S., and C. Tan Courcelle. 2001. Cytomegaloviruses and their replication, p. 2629-2673. In D. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, New York, N.Y.

- 37.Murphy, J. C., W. Fischle, E. Verdin, and J. H. Sinclair. 2002. Control of cytomegalovirus lytic gene expression by histone acetylation. EMBO J. 21:1112-1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nadon, R., and J. Shoemaker. 2002. Statistical issues with microarrays: processing and analysis. Trends Genet. 18:265-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakajima, T., N. Inagaki, H. Tanaka, A. Tanaka, M. Yoshikawa, M. Tamari, K. Hasegawa, K. Matsumoto, H. Tachimoto, M. Ebisawa, G. Tsujimoto, H. Matsuda, H. Nagai, and H. Saito. 2002. Marked increase in CC chemokine gene expression in both human and mouse mast cell transcriptomes following Fcε receptor I cross-linking: an interspecies comparison. Blood 100:3861-3868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pass, R. F. 2001. Cytomegalovirus, p. 2675-2705. In D. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, New York, N.Y.

- 41.Patel, Y., G. Gough, R. S. Coffin, S. Thomas, J. I. Cohen, and D. S. Latchman. 1998. Cell type specific repression of the varicella zoster virus immediate early gene 62 promoter by the cellular Oct-2 transcription factor. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta 1397:268-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Penfold, M. E., D. J. Dairaghi, G. M. Duke, N. Saederup, E. S. Mocarski, G. W. Kemble, and T. J. Schall. 1999. Cytomegalovirus encodes a potent alpha chemokine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9839-9844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pieters, J. 1997. MHC class II restricted antigen presentation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 9:89-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Puskas, L. G., A. Zvara, L. Hackler, Jr., and P. Van Hummelen. 2002. RNA amplification results in reproducible microarray data with slight ratio bias. BioTechniques 32:1330-1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qin, L., P. Qiu, L. Wang, X. Li, J. T. Swarthout, P. Soteropoulos, P. Tolias, and N. C. Partridge. 2003. Gene expression profiles and transcription factors involved in parathyroid hormone signaling in osteoblasts revealed by microarray and bioinformatics. J. Biol. Chem. 278:19723-19731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rajeevan, M. S., S. D. Vernon, N. Taysavang, and E. R. Unger. 2001. Validation of array-based gene expression profiles by real-time (kinetic) RT-PCR. J. Mol. Diagn. 3:26-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Renne, R., C. Barry, D. Dittmer, N. Compitello, P. O. Brown, and D. Ganem. 2001. Modulation of cellular and viral gene expression by the latency-associated nuclear antigen of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 75:458-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rollins, B. J. 1997. Chemokines. Blood 90:909-928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sabatti, C., S. L. Karsten, and D. H. Geschwind. 2002. Thresholding rules for recovering a sparse signal from microarray experiments. Math. Biosci. 176:17-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saederup, N., S. A. Aguirre, T. E. Sparer, D. M. Bouley, and E. S. Mocarski. 2001. Murine cytomegalovirus CC chemokine homolog MCK-2 (m131-129) is a determinant of dissemination that increases inflammation at initial sites of infection. J. Virol. 75:9966-9976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwartz, R., B. Helmich, and D. H. Spector. 1996. CREB and CREB-binding proteins play an important role in the IE2 86-kilodalton protein-mediated transactivation of the human cytomegalovirus 2.2-kilobase RNA promoter. J. Virol. 70:6955-6966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sieff, C., D. Bicknell, G. Caine, J. Robinson, G. Lam, and M. F. Greaves. 1982. Changes in cell surface antigen expression during hemopoietic differentiation. Blood 60:703-713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simmen, K. A., J. Singh, B. G. Luukkonen, M. Lopper, A. Bittner, N. E. Miller, M. R. Jackson, T. Compton, and K. Fruh. 2001. Global modulation of cellular transcription by human cytomegalovirus is initiated by viral glycoprotein B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7140-7145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sinclair, J. H., J. Baillie, L. A. Bryant, J. A. Taylor-Wiedeman, and J. G. Sissons. 1992. Repression of human cytomegalovirus major immediate early gene expression in a monocytic cell line. J. Gen. Virol. 73:433-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Skaletskaya, A., L. M. Bartle, T. Chittenden, A. L. McCormick, E. S. Mocarski, and V. S. Goldmacher. 2001. A cytomegalovirus-encoded inhibitor of apoptosis that suppresses caspase-8 activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7829-7834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Slobedman, B., and E. S. Mocarski. 1999. Quantitative analysis of latent human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 73:4806-4812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Slobedman, B., E. S. Mocarski, A. M. Arvin, E. D. Mellins, and A. Abendroth. 2002. Latent cytomegalovirus down-regulates major histocompatibility complex class II expression on myeloid progenitors. Blood 100:2867-2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soderberg-Naucler, C., D. N. Streblow, K. N. Fish, J. Allan-Yorke, P. P. Smith, and J. A. Nelson. 2001. Reactivation of latent human cytomegalovirus in CD14+ monocytes is differentiation dependent. J. Virol. 75:7543-7554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soderberg-Naucler, C., K. N. Fish, and J. A. Nelson. 1997. Reactivation of latent human cytomegalovirus by allogeneic stimulation of blood cells from healthy donors. Cell 91:119-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stanier, P., D. L. Taylor, A. D. Kitchen, N. Wales, Y. Tryhorn, and A. S. Tyms. 1989. Persistence of cytomegalovirus in mononuclear cells in peripheral blood from blood donors. BMJ 299:897-898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taniguchi, M., K. Miura, H. Iwao, and S. Yamanaka. 2001. Quantitative assessment of DNA microarrays—comparison with Northern blot analyses. Genomics 71:34-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taylor-Wiedeman, J., J. G. Sissons, L. K. Borysiewicz, and J. H. Sinclair. 1991. Monocytes are a major site of persistence of human cytomegalovirus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Gen. Virol. 72:2059-2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taylor-Wiedeman, J., P. Sissons, and J. Sinclair. 1994. Induction of endogenous human cytomegalovirus gene expression after differentiation of monocytes from healthy carriers. J. Virol. 68:1597-1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Gelder, R. N., M. E. von Zastrow, A. Yool, W. C. Dement, J. D. Barchas, and J. H. Eberwine. 1990. Amplified RNA synthesized from limited quantities of heterogeneous cDNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:1663-1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Welcsh, P. L., M. K. Lee, R. M. Gonzalez-Hernandez, D. J. Black, M. Mahadevappa, E. M. Swisher, J. A. Warrington, and M. C. King. 2002. BRCA1 transcriptionally regulates genes involved in breast tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7560-7565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wheeler, D. G., and E. Cooper. 2001. Depolarization strongly induces human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoter/enhancer activity in neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 276:31978-31985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.White, K. L., B. Slobedman, and E. S. Mocarski. 2000. Human cytomegalovirus latency-associated protein pORF94 is dispensable for productive and latent infection. J. Virol. 74:9333-9337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wurmbach, E., T. Yuen, B. J. Ebersole, and S. C. Sealfon. 2001. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor-coupled gene network organization. J. Biol. Chem. 276:47195-47201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xiao, C., B. F. Yang, N. Asadi, F. Beguinot, and C. Hao. 2002. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced death-inducing signaling complex and its modulation by c-FLIP and PED/PEA-15 in glioma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277:25020-25025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yamamoto, K., T. Miyoshi-Koshio, Y. Utsuki, S. Mizuno, and K. Suzuki. 1991. Virucidal activity and viral protein modification by myeloperoxidase: a candidate for defense factor of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes against influenza virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 164:8-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang, I. V., E. Chen, J. P. Hasseman, W. Liang, B. C. Frank, S. Wang, V. Sharov, A. I. Saeed, J. White, J. Li, N. H. Lee, T. J. Yeatman, and J. Quackenbush. 2002. Within the fold: assessing differential expression measures and reproducibility in microarray assays. Genome Biol. 3:research0062.1-0062.12. [Online.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yue, H., P. S. Eastman, B. B. Wang, J. Minor, M. H. Doctolero, R. L. Nuttall, R. Stack, J. W. Becker, J. R. Montgomery, M. Vainer, and R. Johnston. 2001. An evaluation of the performance of cDNA microarrays for detecting changes in global mRNA expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:E41-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yuen, T., E. Wurmbach, R. L. Pfeffer, B. J. Ebersole, and S. C. Sealfon. 2002. Accuracy and calibration of commercial oligonucleotide and custom cDNA microarrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:E48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou, H., H. S. Su, X. Zhang, J. Douhan III, and L. H. Glimcher. 1997. CIITA-dependent and -independent class II MHC expression revealed by a dominant negative mutant. J. Immunol. 158:4741-4749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhu, H., J. P. Cong, G. Mamtora, T. Gingeras, and T. Shenk. 1998. Cellular gene expression altered by human cytomegalovirus: global monitoring with oligonucleotide arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:14470-14475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]