Abstract

Objective

Research conducted on school-based interventions suggests that school connectedness protects against a variety of risk behaviors, including substance abuse, delinquency and sedentary behavior. We extend this line of research by examining the link between college expectations and early adult weight gain using nationally representative panel data from thirty cohorts of American high school seniors followed prospectively to age 30 in the Monitoring the Future Study (1986–2009).

Design and Methods

Growth mixture models identified two latent classes of trajectories of body mass index (BMI) from age 19 to 30: a persistently overweight class (BMI≥25) and a second class exhibiting more moderate growth in BMI to age 30.

Results

Compared to those who did not expect to graduate from college, students fully expecting to graduate from college had 34% lower odds of being in the persistently overweight class (adjusted odds ratio = 0.66, 95% confidence interval = 0.54, 0.81), controlling for academic performance and socioeconomic status.

Conclusions

Successful prevention of obesity early in the life course is based on a multifactorial approach incorporating strategies that address the contexts in which adolescents are embedded. The school setting may be one avenue where successful educational attachment could have positive consequences for subsequent weight gain in early adulthood.

Keywords: Body-Mass Index, Longitudinal, Psychosocial Variables, Weight Gain, Youth

INTRODUCTION

There is a growing literature on the link between the school experience and adolescent health. School attachment or school connectedness (captured, for example, in the form of participation in school sports, less intensive work in paid employment during school years, or college aspirations) have been found to be positively related to adolescent health behaviors (1, 2). For instance, participation in school clubs has been shown to be associated with regular exercise and a healthy diet (3, 4), and with lower rates of cigarette, alcohol, and illicit drug use (5). Conversely, students who work intensively in paid employment during their high school years (i.e. working more than 20 hours per week) are less likely to eat breakfast and tend to get less sleep (6,7).

There is also evidence that school connectedness in adolescence has positive consequences for subsequent health and academic success in early adulthood. Students working intensively in paid employment during high school obtain fewer years of education and are less likely to obtain a college degree (8–11). Using prospective data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (1995–2001), McDade and colleagues (12) found that high school and middle school students who reported a high probability of attending college subsequently exercised more frequently in young adulthood (age 18–26). This finding persisted when controlling for parental education, baseline physical and mental health, family structure, and the student’s school and neighborhood environment.

These findings suggest that young people invest their time in different behaviors depending on their goals or expectations for the future. Within a set of resources and opportunities, an orientation towards the future rather than the present may contribute to healthy behaviors if individuals favor delayed benefits over immediate reward (12). Perceived life chances may play an important role in youth decisions regarding risk and health behaviors, with the result that more forward-thinking adolescents who fully expect to pursue a college education may invest more heavily in a healthy lifestyle in order to meet future goals (13). Holding high the belief in extended education beyond high school captures an adolescent’s “planful competence” (14), including a sense of direction over one’s life. As a result, future expectations with respect to educational attainment may have ensuing consequences for health outcomes such as obesity and overweight through the practice of healthy behaviors over time.

In the United States and much of the developed world the prevalence of obesity has been increasing, with the most rapid increases occurring during the mid-1980s and 1990s (15). Successful prevention of overweight and obesity early in the life course is based on a multifactorial approach incorporating strategies that address the physical and social contexts in which adolescents are embedded (15, 16). The school context may be one avenue where successful school attachment could have positive consequences for subsequent weight gain in early adulthood. However, there is also an issue surrounding reverse causality in this relationship because the stigma of obesity may result in lower school attachment. Indeed, Shore and colleagues (17) found that overweight middle school students had lower grades, more detentions, lower school attendance, and more tardiness than their non-overweight peers. Similarly, in a national sample Crosnoe and Muller (18) found that overweight adolescents had lower academic achievement, especially in schools in which overweight was stigmatized. However, there is also evidence that severely obese adolescents are not more depressed than their peers (19), suggesting that obesity may not be as consequential for psychosocial outlook or future aspirations. Nonetheless, from a policy perspective, promoting school attachment in high risk groups may prove to be a worthwhile initiative regardless of whether obesity surfaced prior to, or in response to, a weak school connection (2, 16, 20).

The purpose of this research was to examine the role of college expectations among high school seniors for subsequent trajectories of weight gain over early adulthood (to age 30). We draw on data from a nationally representative multi-cohort sample of American youth collected prospectively from age 18, which has been ongoing on an annual basis since 1976. As a result, we have the opportunity to examine the role of college aspirations on growth rates of early adult weight gain, accounting for birth cohort. We also control for potentially endogenous factors including academic performance throughout high school and parents’ education, both of which could influence college expectations, weight gain, or both. We hypothesize that controlling for these competing factors, students with higher expectations to graduate from a four year college program will exhibit slower rates of weight gain over early adulthood than those with lower college expectations.

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

Study Population

Data come from the Monitoring the Future (MTF) project, a nation-wide school-based survey of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use, conducted annually in the United States since 1975 (21). The survey also monitors lifestyles and behaviors, including self-reported measures of respondents’ weight and height collected since 1986. MTF is an ongoing cohort sequential study (described in more detail elsewhere (22)) involving a nationally representative sample of high school seniors surveyed in the spring of each year (approximately 15,000 per year). Each year’s data collection takes place in approximately 120 to 146 public and private high schools selected to provide an accurate representative cross-section of 12th graders throughout the coterminous United States.

A representative subsample (approximately 2400 students/year) is randomly selected from each cohort for six biennial follow-ups using self-completed mailed questionnaires to the age of 30 (a half-sample is followed on alternate years); thus, the first follow-up occurs at age 19 or 20, the second at age 21 or 22, and so on. Drug users (regular users of marijuana or any use of illicit drugs in the previous 30 days) were oversampled for participation in the panel component by a ratio of 3 to 1 and then reweighted in the analyses as discussed below. To ease respondent burden, panel respondents are randomly assigned to receive one of five different questionnaires, each with their own set of questions. Since 1986 a random one-fifth of respondents (approximately 480 students per year) received a questionnaire asking about height and weight.

For our purposes we focus on subjects in 30 high school cohorts entering the study between 1976 and 2005 (inclusive) and examine their trajectories of weight gain from age 19 to 30. Because height and weight data were collected beginning in 1986, not all high school cohorts contributed data at all ages, but we make use of a statistical method that takes account of unbalanced designs in order to use data on all cohorts through 2009 (23). This yields a sample of 10,099 individuals who were between the ages of 19 and 30 over this 23 year period. On average, each subject contributed 3.5 observations (± 1.6) over the six follow up periods, generating about 6000 observations at each follow-up. Roughly one-third of the observations span the entire age range of interest (age 19–30). All study procedures are reviewed and approved on an annual basis by the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) for compliance with federal guidelines for the treatment of human subjects.

Measures

Using repeated self-reported measures of height and weight, weight gain over early adulthood was captured with the body mass index (BMI=kg/m2). A BMI of 25–29 is used to define “overweight”, while a BMI score of 30 or above represents “obese”. (BMI scores were not included for women who were pregnant at the time of follow-up.) Three variables capture key indicators of early social position found to be related to life time obesity as well as to school attachment: (i) gender; (ii) race/ethnicity (self-reported by respondents and modeled using three dummy variables contrasting Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other race/ethnic (including Asian) respondents with Non-Hispanic White respondents); and (iii) childhood socioeconomic status (SES) (the maximum of the respondent’s parents’ education, dichotomized as high school degree or less vs. 4-year college degree or higher). We also adjust for cohort differences using 3 ten-year cohorts of high school seniors (1976–1985, 1986–1995, 1996–2005).

Respondents in their senior year of high school were asked about their college expectations with the question, “How likely is it that you will graduate from college (four year program)?” Response options were: definitely won’t, probably won’t, probably will, definitely will. Following McDade and colleagues (12) we classify these response categories according to a probabilistic coding scheme where 0 represents no chance, 0.25 indicates some chance (but probably not), 0.75 indicates a good chance (probably will), and 1.0 captures the expected certainty (definitely will) of college graduation. We also control for high school academic performance, which was asked using an ordinal 9 category measure of each respondent’s average grade throughout high school (e.g. A (93–100), A– (90–92),… D (69 or below)). For analytic purposes, we used the mid-point value of each category (e.g. A=96) to create a continuous index of average high school grade, and divided each value by 10 for the statistical models (range 6.9 to 9.6).

Statistical Analyses

We used generalized growth mixture modeling to identify latent classes of individuals according to their early adult patterns of BMI growth. Growth mixture modeling is an extension of conventional growth modeling that relaxes the assumption of a single population trajectory. By using latent trajectory classes (categorical latent variables), the growth mixture model allows different classes of individuals to vary around different mean growth curves (24). The trajectory of interest in this paper is weight gain (captured with BMI), measured prospectively over young adulthood (age 19 to 30).

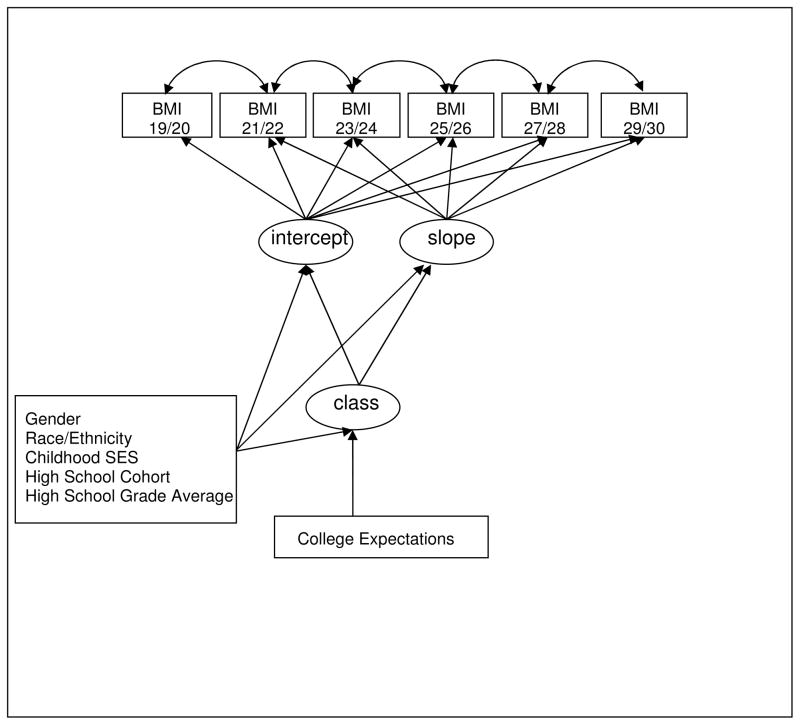

The measurement part of the model captures the growth factors (intercept and slope) as measured by multiple indicators of BMI over time (Figure 1). A linear growth model is specified with equidistant time points, but we also test the fit of a non-linear form by using quadratic terms. The structural part of the model incorporates the growth model within a larger latent variable model by relating the growth factors to other observed and latent variables. Of particular interest is the latent trajectory class variable, which represents the unobserved subpopulation of membership for respondents. This allows a separate growth model for each of the latent classes. College expectations (controlling for school performance, socioeconomic and socio-demographic covariates) predict class membership in a multinomial logistic regression.

Figure 1.

Generalized Growth Mixture Model for BMI over Early Adulthood: the Future Study (age 19–30) 1986–2009

BMI 19/20 - BMI 29/30 refer to BMI scores at each of the 6 waves of data collection (age 19 through age 30)

BMI = Body mass index

SES = Socioeconomic status

Model building proceeded in a sequential process by first specifying the measurement model and then incrementally increasing the number of latent classes. While substantively-based theory is used as the primary means to determine the best fitting model, good fitting models are characterized by (i) a low value for the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC); (ii) a statistically significant (low p-value) Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LMR) likelihood ratio test; and (iii) distinct posterior probabilities for individual class membership (24). All models are estimated in Mplus Version 6.12 (25) using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) with robust standard errors. Multiple random starts are used to minimize local optimal in the likelihood. Respondent-level weights are used to adjust for unequal selection probabilities in the panel study.

Retention rates in the panel respondents are highest in the first follow-up after high school (averaging 70%), and fall to an average of 64% in the biennial follow-ups through to age 30 (25). Using logistic regression analysis (with backward elimination) we modeled the probability of study retention to age 30 according to a broad array of baseline characteristics and found that being Non-Hispanic White, and reporting a higher average grade in high school increased the odds of retention. By including these variables in our models, maximum likelihood produces unbiased coefficients under the assumption that the attrition process is conditional on observed variables in our models (26).

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics, academic indicators, and BMI scores over early adulthood are presented in Table 1. On average respondents had a normal weight in the year following high school (BMI=23.3 (SD=3.7), Table 1) but these cohorts of American youth gained weight steadily over early adulthood, reporting an average BMI of 25.4 (SD=4.3) by age 30. The average reported probability of graduating from a four year college program was 68%. Almost half of the sample fully expected to graduate from a four year college program, while 16% indicated that they definitely would not. On average, respondents reported an average grade throughout high school around 85 (SD=6.95).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Sample (age 19–30) Monitoring the Future Study 1986–2009 (N=10,099)

| Weighted percent or mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | |

| Female | 52.33 % |

| White | 74.20 % |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11.66 % |

| Hispanic | 7.15 % |

| Other race/ethnicity | 6.99 % |

| Childhood SES | |

| Parents have high school education or less | 56.33 % |

| Parents have college degree or higher | 43.67 % |

| Academic Performance and Expectations at Baselinea | |

| Average Grade in High School | 84.64 (6.95) |

| College expectations (probability ranges from 0 to 1.0) | .68 (.35) |

| Definitely won’t (probability=0) | 15.89 % |

| Probably won’t (probability=0.25) | 13.60 % |

| Probably will (probability=0.75) | 22.10 % |

| Definitely will (probability=1.0) | 48.42 % |

| High School Cohort | |

| Class of 1976–1985 | 34.08 % |

| Class of 1986–1995 | 34.78 % |

| Class of 1996–2005 | 31.14 % |

| BMI over Early Adulthood | |

| Age 19/20 | 23.28 (3.70) |

| Age 21/22 | 23.84 (3.89) |

| Age 23/24 | 24.29 (4.07) |

| Age 25/26 | 24.68 (4.17) |

| Age 27/28 | 24.99 (4.18) |

| Age 29/30 | 25.42 (4.26) |

SES=socioeconomic status. BMI=body mass index. SD = standard deviation

Baseline refers to senior year of high school.

Table 2 reports the results and fit statistics for a systematic progression of growth mixture models. The first column presents the results for the single class model. Average BMI at age 19 is 23.1 (intercept) and increases by 0.28 points each year (slope, P<.001) until age 30. There was no evidence of any quadratic form to the models and the distribution of BMI at each time point was roughly normal justifying the linear model. The fit of the model improved by allowing for correlated error between BMI measures at adjacent time points (results not shown; all correlations are statistically significant at P<.0001). The second and third columns of Table 2 report the results for the two-class solution. The change in the BIC and AIC values, coupled with a significant Lo-Mendel-Rubin Likelihood ratio test (P<.001, not shown), suggest that a two class solution is preferable to a single class model. Membership in each class showed good classification quality with individuals most likely to belong to their predicted class (posterior probability is markedly higher (> 0.90) than for the other class). Adding a third class (model not shown) did not result in any improvement in model fit and the posterior probabilities did not differentiate class membership well.

Table 2.

Growth Mixture Model Regression Coefficients for BMI Trajectories Age 19–30 Monitoring the Future Study (1986–2009)33

| Single Class Model | Two-Class Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Overall | Class 1 (78.3%) (Normative Weight Gain) | Class 2 (21.7%) (Persistently Overweight) | |

| Intercept | 23.07*** | 21.65*** | 26.76*** |

| Slope (age) | .28*** | .22*** | .43*** |

| Goodness of Fit | BIC=166471.12 | BIC=163571.72 | |

| Statistics | AIC=166355.60 | AIC=163412.88 | |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

p<.10 (two-tailed tests)

(Note: model allows for growth factors to have different variances in each class)

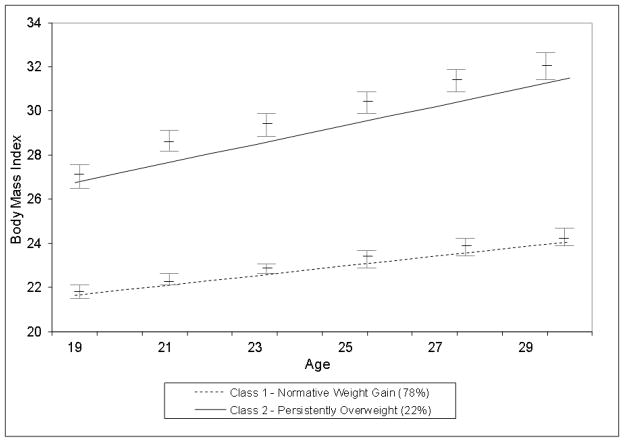

Figure 2 shows the estimated growth curves for BMI from age 19 to 30 according to the 2 class solution. (Observed means and 95% confidence intervals are also presented.) The two curves represent 2 distinct trajectories of BMI growth from early adulthood: Class 1 (with 78.3% of the sample) represents the majority of the sample, which we term the “normative class”, with an average BMI of 21.6 following high school and a steady rate of growth in BMI up to age 30 (slope=.22, P<.001). Conversely, individuals in Class 2 (21.7% of the sample) were on average overweight at high school graduation (mean BMI=26.8) and gained weight more rapidly throughout the next 11 years (slope=.43, P<.001), which we term the “persistently overweight class”. The model supports a class-varying factor covariance matrix, where the growth factor variances are allowed to differ across classes. Results indicate greater variance around the intercept and slope for the persistently overweight class (σ2 = 20.84 and .28, respectively) compared to the normative class (σ2 = 4.01 and .02, respectively).

Figure 2.

BMI Trajectories over Early Adulthood (MTF 1986–2009): Growth Mixture Model Showing 2 Class Solution

Note: Observed BMI means and 95% confidence intervals are also illustrated

- - - - - - - - Class 1 (78%) – Normative Weight Gain

––––––––––––– Class 2 (22%) – Persistently Overweight

The next step in the modeling process adds the covariates to the model, regressing gender, race/ethnicity, childhood SES, high school cohort, academic performance and college expectations on class membership. Table 3 reports the results from the logistic regression for class membership (adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals) using the normative latent class as the reference group. Compared to individuals in the normative class, individuals in the persistently overweight class were more likely to be female, Non-Hispanic Black, and to have parents with a high school education or less. There were strong cohort differences in the odds of class membership, with more recent cohorts of high school seniors more likely to be in the persistently overweight class than those who were high school seniors in the mid-1970’s and early 1980’s. Better academic performance through high school was associated with a reduced odds of being in latent class 2, with each ten point increase in average high school grade associated with a 26% lower odds of being in the persistently overweight class (odds ratio = 0.74, 95% confidence interval = 0.66, 0.83), all other things being equal. Controlling for academic performance and sociodemographic covariates, expecting to graduate from college was associated with reduced odds of membership in the persistently overweight class. Compared to those who did not expect to graduate from college, students fully expecting to graduate from college had a 34% lower odds of being in the persistently overweight class (adjusted odds ratio = 0.66, 95% confidence interval = 0.54, 0.81), controlling for academic performance, childhood SES and other covariates.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression for Latent Class Membership: Monitoring the Future Study (age 19–30) 1986–2009

| Latent Class 2† (Persistently Overweight) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Coefficient | OR (95% CI) | |

| Femalea | .36** | 1.43 (1.13, 1.82) |

| Non-Hispanic Blackb | .61*** | 1.83 (1.36, 2.48) |

| Hispanicb | .26 | 1.29 (0.90, 1.86) |

| Otherb | .06 | 1.06 (.76, 1.46) |

| Low Childhood SESc | .51*** | 1.67 (1.40, 2.00) |

| High School Cohort 1986–1995d | .82*** | 2.27 (1.84, 2.80) |

| High School Cohort 1996–2005d | 1.12*** | 3.07 (2.42, 3.90) |

| College Expectations | −.41*** | 0.66 (0.54, 0.81) |

| Average Grade in High School | −.30*** | .74 (.66, .83) |

Latent Class 1 (normative weight gain) is the reference class

Reference group is Male

Reference group is White

Refers to those whose parents have a high school education or less; reference group is parents with a college degree or higher

Reference group is high school cohort 1976–1985

SES=socioeconomic status

OR = adjusted odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001 (two-tailed tests)

The model also captures latent class-specific effects of the covariates on the growth factors. Table 4 presents the unstandardized regression coefficients (with standard errors) for the effects of the covariates on BMI intercept and slope for each of the two latent classes. Within the persistently overweight class, the rate of growth in BMI is more rapid for women and for those in more recent high school cohorts. Those who were high school seniors after 1995 also had significantly higher BMI at age 19/20 (intercept) than those who graduated from high school in earlier years. Within the normative class, women and other race/ethnic groups had significantly lower BMI at baseline, but non-Hispanic Blacks, and those with low childhood SES experienced more rapid growth in BMI in this class; women experienced less rapid growth. Cohort differences were also observed in the normative class, with more recent cohorts having significantly higher BMI at baseline (age 19/20) and significantly more rapid increase in BMI over early adulthood. We also ran a similar sequence of models stratified by gender, but there were no differences in effects between men and women.

Table 4.

Regressing Growth Parameters on Sociodemographic Characteristics by Latent Class of BMI Trajectory: Monitoring the Future Study (age 19–30) 1986–2009

| Latent Class 1 (Normative Class) | Latent Class 2 (Persistently Overweight) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | |

| Femalea | −2.04*** (.09) | −.10*** (.01) | .18 (.27) | .23*** (.03) |

| Blackb | .27 (.16) | .08*** (.02) | .46 (.51) | .04 (.05) |

| Hispanicb | .25 (.19) | .04 (.03) | .47 (.53) | .03 (.06) |

| Otherb | −.60*** (.15) | −.01 (.02) | −.95* (.46) | −.01 (.06) |

| Low Childhood SESc | −.13 (.08) | .03*** (.01) | .12 (.28) | .01 (.03) |

| High School Cohort 1986–1995d | .22* (.09) | .04*** (.01) | −.01 (.39) | .15*** (.04) |

| High School Cohort 1996–2005d | .62*** (.12) | .03 (.01) | 1.92*** (.45) | .21*** (.05) |

Note: cell entries are unstandardized regression coefficients; standard errors are in parentheses under the parameter estimates.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001 (two-tailed tests)

SES=socioeconomic status

Reference group is Male

Reference group is White.

Refers to those whose parents have a high school education or less; reference group is parents with a college degree or higher.

Reference group is High School Cohort 1976–1985.

DISCUSSION

Using data from a multi-cohort national sample of high school seniors followed throughout early adulthood, this paper examined the role of college expectations for subsequent weight gain over early adulthood. On average, these high school seniors reported a 68% chance that they would graduate from a four year college program, slightly lower than the probability reported elsewhere by younger adolescents (grades 7 through 11) (12), which asked only about the expectation of attending college (not graduating from a four year degree program). Yet, having these expectations was associated with less rapid weight gain over early adulthood. This finding was independent of socioeconomic and sociodemographic confounders as well as academic performance throughout high school.

Evidence suggests that diminished expectations for the future may undermine the adoption of positive health behaviors related to obesity, including exercise and healthy eating (13). As argued by McDade and colleagues (12), the extent to which individuals favor immediate utility over delayed utility may influence health behaviors that lead to weight gain at this life stage. Fostering school attachment, particularly through the promotion of norms and expectations for academic pursuits in the school setting, may therefore have positive consequences for adolescent weight gain over time (2). The transition to adulthood (sometimes referred to as emerging or early adulthood (27)) is particularly important because individuals are on their own typically for the first time, when life plans are put into action, and when trajectories of risk become more manifest (28). As a result, this may be a particularly salient period of adolescent development for obesity prevention and intervention strategies. To the extent that adolescents are bonded or attached to schools at this life stage, their adoption of forward-thinking expectations is encouraged because they are motivated to conform to the norms, expectations, and values of that socialization unit (29). For example, adolescents who are poorly bonded to school are more likely to use cigarettes and alcohol than adolescents who are well bonded to school (30, 31).

Our results extend this line of thinking by suggesting a broader construct termed “educational connectedness,” measured here in terms of college expectations, has positive consequences for moderate growth in BMI over early adulthood. Whereas school connectedness relates to the experiences during adolescence in terms of connections with the school context, educational connectedness relates to the long-term belief in the power and importance of education in setting the stage for competence across the life course (14). Holding high the belief in extended education beyond high school captures an adolescent’s “apparent readiness to take responsibility for self” (14:806), including beliefs in individual control over life direction and health behaviors.

The connection between college expectations and trajectories of BMI may also be a function of actually obtaining a college degree in early adulthood. However, this is complicated in that obese adolescents, especially obese girls, are less likely to attend college than their non-obese age-mates (32), yet college attendance is typically associated with weight gain, at least initially (33). A lack of complete data on actual college graduation in these data prevented us from assessing the mediating role of college degree for college expectations. However, replicating our analysis with a half sample of respondents with complete data on college graduation showed no difference in the effects of college expectations on latent class membership.

Our results also identified strong and persistent cohort differences in trajectories of weight gain over early adulthood, which parallel the observed increase in the rates of obesity and overweight in the United States since the mid-1980s (15). More recent cohorts of high school seniors were more likely to be in the persistently overweight class than those who were high school seniors in the mid-1970’s and early 1980’s. Even within each trajectory class, more recent high school cohorts also had higher BMI at age 19/20 and faster rates of growth in BMI through to age 30. Consistent with the existing research (34), we also noted significant gender, socioeconomic, and race/ethnic disparities in the propensity to be in the persistently overweight trajectory, as well as in the rates of growth in BMI over early adulthood.

Strengths and Limitations

There are noteworthy strengths of this study. The use of nationally representative, multi-cohort, multi-wave prospective longitudinal data spanning the transition to adulthood provides a strong methodological foundation for the findings, allowing a level of confidence beyond what is typical in the literature. In addition, we use leading edge statistical strategies to control for potential confounds and identify and predict distinct time-varying latent classes of BMI. There are also noteworthy limitations. Our study is limited by self-reported measures of height and weight, which tend to be underestimated (35). However, self-reported values of height tend to be highly correlated with their measured values (36, 37), making them useful for assessing population trends over time. Measures of weight-related health behaviors were also unavailable in these data, preventing us from testing the mediating role of health behaviors in the pathway between college expectations and weight gain through to age 30. In addition, it is unclear whether the relationship between college expectations and weight gain reflects preexisting differences among students in terms of socioeconomic background, orientations towards further education and weight-related health behaviors. For example, overweight youths from a lower socioeconomic background with poor access to healthy foods and limited opportunities for exercise may also have low expectations for college attendance. While we attempted to control for these common causes in our analyses, we cannot rule out the role of unobserved variables.

Our main independent variable of interest, college expectations, captures many factors which could be operating in weight gain in early adulthood. Much of the existing research looking at health behaviors has examined school connectedness in terms of participation in school clubs and sports, and one recent study (12) examined the link between college expectations and physical activity. We further this area of research by considering the implications of college expectations as a marker for the way young adults assess their future trajectory and their health and lifestyle choices along the way. However, it is noteworthy that in a separate regression model (results not shown), college expectations were significantly associated (p<.01) with other measures of school attachment available in our data, including liking school, the perception that school has meaning, satisfaction with overall educational experience, and number of days skipped school (negatively associated) (controlling for gender and race/ethnicity). However, these measures were not significantly associated with BMI trajectories in our models.

What happens at school is critically important for adolescent health and development (38) and schools have been identified as a key setting for public health strategies to lower or prevent the prevalence of overweight and obesity (39, 40). Beyond strategies designed to promote physical activity or limit the availability of snacks and soft drinks, research conducted on school-based interventions suggests that school connectedness serves to protect against a variety of risk behaviors, including substance abuse, delinquency and sedentary behavior (2, 3, 30). We extend this line of research by examining the link between college expectations and early adult weight gain. Results suggest that attention to subjective life chances may provide opportunities for intervention in school settings, particularly in the form of discussions about college attendance and fostering a commitment to academic goals, with potential benefits for healthy weight gain over early adulthood.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, as part of the Youth, Education, and Society (YES) Project (64703). YES is an integral part of a larger research initiative of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation entitled Bridging the Gap: Research Informing Practice and Policy for Healthy Youth Behavior. “Bridging the Gap” utilizes data from the Monitoring the Future study (MTF), funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, a part of the National Institutes of Health. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the sponsors.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.McNeely CA, Nonnemaker JM, Blum RW. Promoting School Connectedness: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of School Health. 2002;72(4):138–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb06533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School Connectedness: Strategies for Increasing Protective Factors Among Youth. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison PA, Narayan G. Differences in Behavior, Psychological Factors, and Environmental Factors Associated with Participation in School Sports and Other Activities in Adolescence. Journal of School Health. 2003;73(3):113–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2003.tb03585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pate RR, Trost SG, Levin S, Dowda M. Sports Participation and Health-Related Behaviors Among US Youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(9):904–11. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.9.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncan S, Duncan T, Strycker L. Risk and protective factors influencing adolescent problem behavior: A multivariate latent growth curve analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2000;22(2):103–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02895772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachman JG, Schulenberg J. How part-time work intensity relates to drug use, problem behavior, time use, and satisfaction among high school seniors: Are these consequences or merely correlates? Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(2):220–35. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staff J, Messersmith EE, Schulenberg JE. Adolescents and the world of work. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2009. pp. 270–313. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JC, Staff J. When Work Matters: The varying impact of work intensity on high school dropout. Sociology of Education. 2007;80(2):158–78. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staff J, Mortimer JT. Educational and work strategies from adolescence to early adulthood: Consequences for educational attainment. Social Forces. 2007;85(3):1169–94. doi: 10.1353/sof.2007.0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carr RV, Wright JD, Brody CJ. Effects of High School Work Experience a Decade Later: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Survey. Sociology of Education. 1996;69(1):66–81. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachman JG, Staff J, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Freedman-Doan P. Twelfth-grade student work intensity linked to later educational attainment and substance use: New longitudinal evidence. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(2):344–63. doi: 10.1037/a0021027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDade TW, Chyu L, Duncan GJ, Hoyt LT, Doane LD, Adam EK. Adolescents’ expectations for the future predict health behaviors in early adulthood. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73(3):391–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jessor R, Donovan JE, Costa F. Personality, perceived life chances, and adolescent behavior. In: Hurrelmann K, Hamilton SF, editors. Social problems and social contexts in adolescence: Perspectives across boundaries. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1996. pp. 219–33. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clausen JS. Adolescent competence and the shaping of the life course. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;96:805–842. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and Trends in Obesity Among US Adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, et al. Protecting Adolescents From Harm. JAMA. 1997;278(10):823–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shore SM, Sachs ML, Lidicker JR, Brett SN, Wright AR, Libonati JR. Decreased Scholastic Achievement in Overweight Middle School Students. Obesity. 2008;16(7):1535–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crosnoe R, Muller C. Body mass index, academic achievement, and school context: Examining the educational experiences of adolescents at risk of obesity. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2004;45:393–407. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman E, Must A. Depressive symptoms in severely obese compared with normal weight adolescents: results from a community-based longitudinal study. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(1):64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blum R, McNeely C, Rinehart P. Improving the odds: the untapped power of schools to improve the health of teens. Minneapolis: Center for Adolescent Health and Development, University of Minnesota; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2008: Volume 1, Secondary school students. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008. Report No.: NIH Publication No. 07-6205 Contract No.: NIH Publication No. 09-7402. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM. The Monitoring the Future project after thirty-two years: Design and procedures. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 2006. Report No.: 64. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singer JD, Willet JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muthen B, Muthen LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modelling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24(6):882–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muthen BO, Muthen LK. MPlus User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen and Muthen; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cnaan A, Laird NM, Slasor P. Using the general linear mixed model to analyse unbalanced repeated measures and longitudinal data. Statistics in Medicine. 1997;16(20):2349–80. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971030)16:20<2349::aid-sim667>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnett JJ, Taber S. Adolescence terminable and interminable: When does adolescence end? Journal of Youth and Adolesence. 1994;23:517–37. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Early adult transitions and their relation to well-being and substance use. In: Settersen RA Jr, Furstenberg FF Jr, Rumbaut RG, editors. On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy. University of Chicago Press; 2005. pp. 417–53. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henry KL, Oetting ER, Slater MD. The Role of Attachment to Family, School, and Peers in Adolescents’ Use of Alcohol: A Longitudinal Study of Within-Person and Between-Persons Effects. J Couns Psychol. 2009 Oct 1;56(4):564–72. doi: 10.1037/a0017041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, Freedman-Doan P, Messersmith EE. The education-drug use connection: How successes and failures in school relate to adolescent smoking, drinking, drug use, and delinquency. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates/Taylor & Francis; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bryant AL, Schulenberg JE, et al. How Academic Achievement, Attitudes, and Behaviors Relate to the Course of Substance Use During Adolescence: A 6-Year, Multiwave National Longitudinal Study. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13(3):361–397. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crosnoe R. Gender, obesity, and education. Sociology of Education. 2007;80:241–260. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vella-Zarb RA, Elgar FJ. ‘Freshman 5’: A meta-analysis of weight gain in the freshman year of college. Journal of American College Health. 2009;58:161–166. doi: 10.1080/07448480903221392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paeratakul S, Lovejoy JC, Ryan DH, Bray GA. The relation of gender, race, and socioeconomic status to obesity and obesity comorbidities in a national sample of US adults. International Journal of Obesity. 2002;26:1205–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart AW, Jackson RT, Ford MA, Beaglehole R. Underestimation of relative weight by use of self-reported height and weight. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1987;125(1):122–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodman E, Hinden BR, et al. Accuracy of Teen and Parental Reports of Obesity and Body Mass Index. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1):52–58. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brener ND, McManus T, et al. Reliability and validity of self-reported height and weight among high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;32(4):281–287. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00708-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crosnoe R. Fitting in, standing out: navigating the social challenges of high school to get an education. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Institute of Medicine. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Story M, Nanney MS, Schwartz MB. Schools and Obesity Prevention: Creating School Environments and Policies to Promote Healthy Eating and Physical Activity. Milbank Quarterly. 2009;87(1):71–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]