Abstract

In this review, we develop the argument that the molecular/cellular mechanisms underlying learning and memory are an adaptation of the mechanisms used by all cells to regulate cell motility. Neuronal plasticity and more specifically synaptic plasticity are widely recognized as the processes by which information is stored in neuronal networks engaged during the acquisition of information. Evidence accumulated over the last 25 years regarding the molecular events underlying synaptic plasticity at excitatory synapses has shown the remarkable convergence between those events and those taking place in cells undergoing migration in response to extracellular signals. We further develop the thesis that the calcium-dependent protease, calpain, which we postulated over 25 years ago to play a critical role in learning and memory, plays a central role in the regulation of both cell motility and synaptic plasticity. The findings discussed in this review illustrate the general principle that fundamental cell biological processes are used for a wide range of functions at the level of organisms.

Keywords: actin polymerization, cell motility, synaptic plasticity, calpain, learning and memory

1. Introduction

Learning and memory is a property of all living organisms, and thus it must have appeared very early during evolution. Consequently, the underlying cellular mechanism(s), or at least some primitive form(s) of it, must also have appeared very early during evolution. While learning and memory has been reported in unicellular organisms, it is only in more complex organisms that learning and memory has been extensively studied at the molecular and cellular levels. Indeed, some forms of learning and memory have been found in invertebrates as well as in early vertebrates (Benfenati, 2007). It is generally assumed that learning and memory is due to the plasticity of the nervous system, a notion going back to James, Tanzi and Cajal, over a century ago (see (Berlucchi and Buchtel, 2009) for a review). This concept has been further expanded to that of synaptic plasticity, and the search for the mechanisms of learning and memory at the molecular level has thus focused on those mechanisms that can account for activity-dependent modifications of synaptic strength. In this review we will argue that learning and memory is an emerging property of cell motility, a process that also evolved very early in unicellular organisms, and was further developed in multicellular organisms. Nevertheless, the basic machinery used by unicellular organisms to navigate through the environment remained present in every cell of complex organisms and was adapted to serve a variety of functions related to cell division, contraction, extension, movement and cell-cell interactions. As we will discuss, this basic machinery is extremely complex and involves a multitude of molecular components that have evolved and intermingled with other cellular components regulating other cell functions, including cell signaling, transcription and translation. Interestingly, the majority of proteins present in mammalian postsynaptic densities contributes to generic cellular functions, including protein synthesis and degradation, vesicular trafficking and regulation of actin cytoskeleton, and is found in most organisms from yeasts to invertebrates and vertebrates (Emes et al., 2008). In neurons, the cell motility machinery is used during various phases of developmental growth and expansion, and, we will argue, for producing long-lasting changes in structure and function in certain subcellular compartments, such as dendritic spines in adult organisms. We will first review the basic mechanisms involved in cell motility, focusing on the role of actin polymerization, and of the plasma membrane, which provides for the dynamic integration of major components regulating motility. We will then discuss the specific adaptation of the machinery to neurons, both during development when neurons are actively growing and establishing synaptic connections, as well as in the adult when motility is restricted to specific subcellular compartments. This will be followed by a brief review of the features of and mechanisms underlying synaptic plasticity in adult brain, with an emphasis on long-term potentiation (LTP) of synaptic transmission at hippocampal synapses, a phenomenon widely recognized as one of the mechanisms underlying memory formation in mammalian brain. We will develop the argument that many of the molecular events involved in LTP induction and consolidation are adaptations of the events underlying cell motility. We will conclude our review by discussing how the understanding of this commonality between learning and memory and cell motility might shed new light on the understanding of several disorders associated with learning and memory impairments.

2. Regulation of cell motility

Since numerous reviews have been written on the subject of cell motility (Allard and Mogilner, 2013; Levayer and Lecuit, 2012; Rottner and Stradal, 2011), we will provide a simplified version of the complex mechanisms that are involved in the regulation of cell motility. In particular, we will focus on actin filaments and the role of specific areas of the plasma membrane in the control of cell movement. Actin filaments are formed by polymerization of globular actin, G-actin, the most abundant protein in all eukaryotic cells, into filamentous actin, F-actin. This process requires ATP, which is hydrolyzed after subunit addition, as well as K+ and Mg2+. While actin filaments can form in vitro by polymerization from actin monomers into oligomers followed by rapid elongation until a steady-state is reached when rate of depolymerization equals rate of polymerization, the process taking place inside cells is regulated by numerous interacting proteins (Dominguez and Holmes, 2011; Pollard and Cooper, 2009). A major regulator of actin polymerization consists in the actin-binding protein, cofilin, which severs actin filaments. The activity of cofilin itself is regulated by phosphorylation mediated by LIM kinase, which inactivates cofilin, thereby facilitating actin filament elongation. Thus, actin filaments are generally in a dynamic state, also called treadmilling, where actin monomers are added to the + or barbed end, and dissociate at the − or pointed end. Because the rate of addition of G-actin at the + end equals the rate of removal of G-actin at the − end under steady state, the length of the actin filament remains the same but the filament appears to move in the direction of the end. Several mechanisms are used to elongate actin filaments; in particular, inactivation of cofilin by phosphorylation reduces the rate of G-actin removal, thus favoring elongation. Alternatively, nucleation and branching of actin filaments also promote actin filament elongation.

Cell motility is the result of the ability of cells to extend small projections, called lamellipodia, which are mostly composed of actin filaments, with fast growing ends, also known as the barbed ends, facing the leading edge of the cell. To do so, new actin filaments are formed by the binding of the Arp2/3 complex together with a number of proteins from the WASp/Scar/WAVE family (Machesky and Insall, 1998; Rogers et al., 2003). Filament growth is generally terminated by end-capping with a number of different capping proteins. Actin filaments also form elongated networks due to interactions with a number of actin-binding proteins (ABPs) and cross-linkers (a-actinin, fascin, and filamin) (Michelot and Drubin, 2011). The rapid addition of actin monomers to the barbed ends generates a force that is critical for pushing the leading edge forward and for a backward movement of the actin filament network, resulting in retrograde F-actin flow (Pollard and Borisy, 2003). This rapid elongation is facilitated by proteins of the Ena/VASP family (Bear et al., 2002). Cell migration and therefore cell motility are necessarily coordinated with interactions with the extracellular matrix (ECM) (Gardel et al., 2010). In particular, this process requires the spatio-temporal integration of 2 opposite events: forward movement of the leading edge and release of the adhesion of the cell to the rear ECM (Fig. 1). Actin filaments are coupled to the ECM through complex assemblies of structural and signaling proteins referred to as focal adhesions (FAs). The Rho family GTPases, Rho, Rac and Cdc42, play a critical role in this regulation. Cdc42 is involved in filipodia formation, Rac in the formation of rufles and Rho in the formation of stress actin filaments. RhoA stimulates ROCK, which in turn phosphorylates/activates LIM kinase resulting in cofilin phosphorylation and inactivation, thereby stabilizing actin filaments (Stanyon and Bernard, 1999). Rac and Cdc42 activate p21-activated kinases (PAKs), which activate a number of downstream effectors, including myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), paxillin, filamin A and cortactin, thereby also regulating cell motility (Kumar et al., 2009). In order to mediate contraction, which is also required for cell migration, cells rely on interactions between F-actin and myosin, a family of ATP-dependent motor proteins. In addition, both protrusion and contraction need to be closely coordinated to adhesion at the leading edge and deadhesion at the rear end (Fig. 1). Focal adhesion complexes also involve integrins, which bind ECM from their extracellular domains when activated and actin filaments through their intracellular domains (Roca-Cusachs et al., 2012). Binding of integrins to ECM is generally thought to be required to promote the maturation of FAs, with the recruitment of a-actinin and talin (Choi et al., 2008). Talin plays therefore a critical role in the regulation of cell adhesion and motility, as it directly binds with integrin and actin filaments.

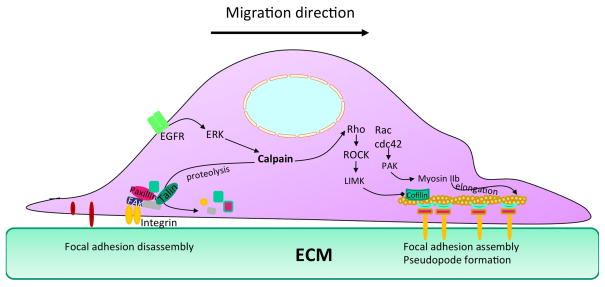

Figure 1. Roles of calpain in the generic mechanism of cell motility.

Cell motility involves several mechanisms that are required for actin polymerization and actin filament elongation at the leading edge of the cell and detachment of the cell from the rear end. Calpain activation has been shown to be involved in the disassembly of focal adhesion sites through talin degradation and to actin polymerization regulation through RhoA truncation. Other critical elements of actin polymerization are depicted in the diagram, including the small GTPases, Rac and cdc42, as well as PAK and myosin IIb. The EGF receptor has been shown to activate m-calpain through ERK-mediated phosphorylation (adapted from (Frame et al., 2002)).

A major regulatory element of cell migration is the neutral, calcium-dependent protease calpain (Perrin and Huttenlocher, 2002). Calpain is a unique protease in the sense that when calpain cleaves its substrates it generates fragments with different structure/functions than the native proteins (Campbell and Davies, 2012). In particular, the β-integrin cytoplasmic domain and talin are both calpain substrates (Fox, 1999). It has also been proposed that calpain is upstream of Rho and could therefore participate in the forward movement of cells during migration (Sato and Kawashima, 2001). In addition, calpain, by cleaving talin, has been proposed to modify the structure of FAs and thus to facilitate de-adhesion at the rear end of migrating cells. In support of this, calpain inhibition suppresses cell migration by impairing retraction at the rear end of migrating cells (Huttenlocher et al., 1997; Palecek et al., 1998). Furthermore, calpain also cleaves Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK), a kinase that also plays an important role in the stabilization of FAs (Carragher et al., 2003). Similarly, calpain, by cleaving the cytoplasmic domain of β-integrin would stimulate cell spreading and inhibit lamellipodia formation (Kulkarni et al., 1999; Sato and Kawashima, 2001). Interestingly, calpain appears to function as a molecular switch to control cell spreading and retraction in Chinese hamster ovary cells (Flevaris et al., 2007). In this system, activation of cell adhesion receptors belonging to the integrin family results in calpain activation and, depending on the state of phosphorylation of the integrin cytoplasmic domain, leads to either inhibition of RhoA and spreading or activation of RhoA and cell retraction. RhoA has been shown to be a calpain substrate, thus providing a clear path to link calpain activation to actin polymerization (Kulkarni et al., 2002). EGF has been shown to stimulate cell motility through a reduction of cell adhesion to ECM. EGF treatment of fibroblasts results in the rapid stimulation of calpain activity, while calpain inhibition prevents EGF-stimulated cell de-adhesion and migration. These effects of EGF were found to be due to EGF-mediated activation of the ERK/MAPK signaling pathway, resulting in calpain-2 phosphorylation and activation (Glading et al., 2001). In addition, inhibition of MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK) prevented EGF-elicited calpain activation; in contrast, expression of a constitutively active form of MEK activated calpain in the absence of EGF. It is now generally admitted that ERK-mediated calpain-2 phosphorylation and activation accounts for EGF effects on cell adhesion and motility (Fig. 1).

Summary

Cell motility is based on the integration of actin filament regulation and cell-cell interaction signaling. Calpain plays a critical role in this process because it is specifically activated by cell-cell interaction signaling and it regulates both actin filament assembly/disassembly and the interaction between cells.

3. Neuronal motility

3.1. Axonal elongation

In addition to cell migration, neurons have a unique specialization requiring extensive motile mechanisms, which is related to neurite extension and axonal growth during the development of the nervous system. While the exact mechanisms involving axonal growth are still not completely understood, a certain number of features have been identified. In particular, it is now clear that axon elongation is the result of cytoskeletal dynamics involving tubulin and actin polymerization at the tip of the growing axon, a.k.a. the growth cone (Suter and Miller, 2011). In addition, axonal elongation requires forces that are generated by motor proteins, such as kinesin, dynein and myosin. Such forces produce forward movement of the growth cone and stretching of the axon. Dynamics of actin and tubulin within the growth cones are therefore the critical elements responsible for axonal elongation (Suter and Miller, 2011). The growth cone consists of lamellipodia and filopodia, and the same general mechanisms discussed above for cell motility are involved in the dynamics of the growth cone (Mattila and Lappalainen, 2008). However, growth cones have to be able to respond to a large number of extracellular signals to regulate the direction as well as the rate of growth (Dudanova and Klein, 2013; Vitriol and Zheng, 2012). This constraint imposes a tight regulation between these signaling mechanisms and the regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics involved in cell motility. Calcium, p53, PTEN and calpain have recently been found to play critical roles in the integration of extracellular signals and the regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics that determine the movement of the growth cones.

Calcium is a major second messenger inside neurons, as changes in calcium concentration result from both electrical activity in response to the activation of various voltage-gated channels, as well as from extracellular stimuli acting through other intracellular pathways to release calcium from internal stores (Zheng and Poo, 2007). While all these signals produce changes in intracellular calcium concentration, it appears that there are 3 different patterns of calcium signals that are used by growth cones to respond differentially to these signals: small and large amplitudes of calcium signals result in retraction of the growth cones, whereas medium amplitude calcium signals result in elongation (Gomez and Zheng, 2006). As expected, a variety of calcium-dependent protein kinases and phosphatases are involved in these processes. However, it is the interactions of calcium with the Rho GTPases mentioned above, RhoA, Rac and Cdc42, which are crucial to determine the integration of calcium signals with cytoskeletal dynamics, and to regulate the response of the growth cone to various stimuli. Thus, RhoA is generally involved in growth cone collapse, whereas Rac and Cdc42 are involved in growth cone elongation and turning (Dickson, 2001). Calcium regulation of these Rho GTPases is mediated by multiple guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) (Aspenstrom, 2004). Calcium interaction with myosin II is also a critical element linking extracellular stimuli to changes in growth cone motility.

The tumor suppressor p53 has also recently been shown to participate in the regulation of axonal outgrowth through a non-transcriptional effect involving local regulation of the Rho kinase (ROCK) signaling pathway that controls these dynamics through LIM kinase and cofilin. Thus, NGF-induced neurite growth in PC12 cells and in cultured cortical neurons depends on the presence of functional p53 (Fabian et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2006), possibly through increased expression of coronin 1b (a filamentous actin binding protein) and the small GTPase, Rab13 (Di Giovanni et al., 2006). We also recently showed that phosphorylated p53 (p-p53) was abundantly present in axons and growth cones and that p53 suppression by inhibitors or siRNA induced rapid growth cone collapse (Qin et al., 2009).

PTEN (Phosphatase and Tensin homolog) is a negative regulator of the PI3K/Akt and mTOR pathways and is therefore widely implicated in linking extracellular stimuli to regulation of growth processes through the control of protein synthesis (Ning et al., 2010). PTEN deletion results in increased growth cone size and stimulates axonal elongation, and enhances regeneration of adult corticospinal projections (Liu et al., 2010). This property has been shown to be potentially beneficial for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), as PTEN depletion in motoneurons from mice defective in the survival motor neuron (SMN) gene resulted in increased axonal growth and survival (Ning et al., 2010). PTEN also dephosphorylates FAK and thereby plays an important role in controlling cell growth, invasion, migration and focal adhesion (Tamura et al., 1999).

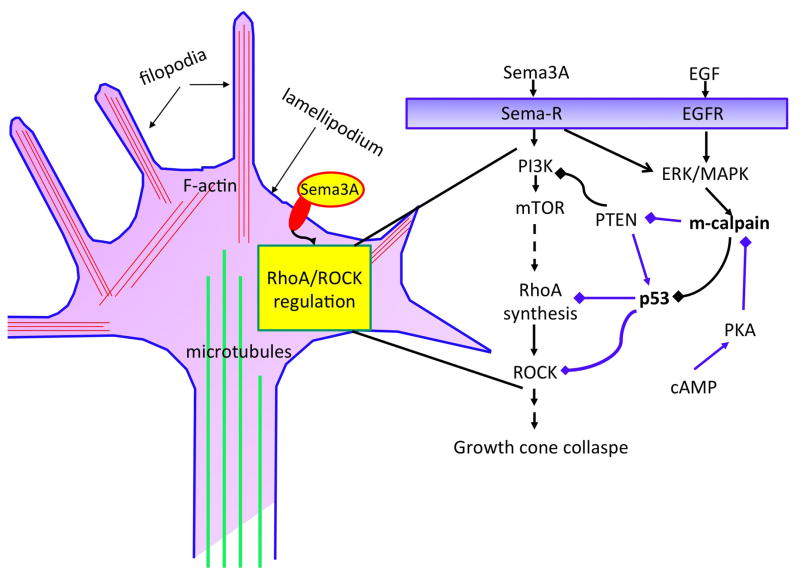

Calpains represent a family of calcium-dependent proteases, which has now 15 members. μ-Calpain and m-calpain are ubiquitously expressed in brain, and the major difference between these 2 isoforms is their calcium dependency for activation, with μ-calpain requiring micromolar concentration whereas m-calpain requires millimolar calcium concentration (Campbell and Davies, 2012). We and others have shown that m-calpain activation is also regulated by phosphorylation (Glading et al., 2004; Zadran et al., 2010). In particular, while ERK-mediated phosphorylation at Serine 50 activates m-calpain, PKA-mediated phosphorylation at serine 369 inactivates it. As mentioned previously, calpain, by truncating a variety of proteins, plays a critical role in the regulation of shape and motility in numerous cell types [see (Carragher and Frame, 2002; Perrin and Huttenlocher, 2002) for reviews], and calpain has been shown to be involved in growth cone responses to extracellular signals (Robles et al., 2003; To et al., 2007). We recently found that calpain-mediated truncation of the p-p53 plays a major role in regulating axonal growth cone growth (Qin et al., 2010b). We first showed that p-p53 played a critical role in growth cone regulation through a dual effect: i) p-p53 interferes with ROCK signaling by inhibiting RhoA synthesis, and ii) p-p53 interferes with ROCK signaling by directly binding to ROCK (Qin et al., 2010a). Thus calpain-mediated truncation of p-p53 eliminates this dual action of p-p53, i.e., to increase ROCK activity, which in turns induces actin filament contraction and growth cone collapse (Gallo, 2006; Zhang et al., 2003) (Fig. 2). We also recently found that calpain truncates PTEN, resulting in mTOR activation and stimulation of local protein synthesis (Briz et al., 2013). Interestingly calpain-mediated truncation of PTEN and p-p53 has opposite effects on growth cone behavior, with the former resulting in growth cone elongation and the latter in growth cone collapse.

Figure 2. Roles of calpain in axonal growth cone growth or collapse.

Semaphorin 3A produces a rapid growth cone collapse (left side). We previously showed that calpain, by cleaving p-p53, was involved in the regulation of RhoA synthesis and the activity of ROCK/LIM kinase pathway, and therefore in disruption of the actin network and growth cone collapse (Qin et al., 2010b). Recent findings indicate that while m-calpain is activated by ERK/MAPK-mediated phosphorylation, which is downstream of semaphorin receptor and EGFR activation, it is suppressed by cAMP-induced PKA activation (right side). The findings that m-calpain activation results in PTEN degradation, and activation of the mTOR pathway suggest the existence of more complex interactions between proteolysis and protein synthesis through the mTOR pathway. The spatio-temporal regulation of these complex events will determine the fate of the growth cone, either growth or collapse. Blue lines in the right side panel indicate events potentially linked to growth cone growth.

All these findings therefore demonstrate the existence of a new mechanism linking extrinsic and intrinsic signals to the regulation of axonal outgrowth. Calpain, and in particular m-calpain, is ideally suited to integrate these various signals, as a result of its dual regulation by MAPK- and PKA-mediated phosphorylation, and, by truncating various proteins participating in the regulation of actin dynamics, to provide a critical switch for axonal outgrowth or retraction. In particular, the role of cAMP in axonal growth has been widely documented (Lohof et al., 1992; Ming et al., 1997). It is therefore tempting to propose that cAMP, by activating PKA and inhibiting m-calpain, protects p-p53 from degradation, thereby promoting axonal outgrowth. It is also tempting to speculate that interactions between PTEN and p53 could play a role in regulating the effects of calpain on growth cone. In particular, we propose that PTEN-mediated dephosphorylation of p-p53 would protect it from calpain-mediated truncation, resulting in the existence of a negative feed-back regulation that would limit the extent of either growth or collapse. Furthermore, calpain-mediated PTEN truncation and mTOR activation provides a necessary link between growth and protein synthesis. Interestingly, a role for calpain in adult axonal regeneration/degeneration has also been discussed (Hou et al., 2008), suggesting that the function of calpain in regulation of axonal growth extends beyond the developmental period.

3.2. Dendritic spine formation

While the mechanisms involved in dendritic spine formation are not completely understood, it is generally admitted that spines are formed by the initiation of a filopodium and its elongation (Hotulainen and Hoogenraad, 2010). This process would involve the typical machinery required for filopodium formation, that is, attachment of Ena/VASP proteins to actin filaments and branching of the filaments with Arp2/3 complex for spine head expansion. In addition, the small GTPAse Rif and its effector mDia2, as well as myosin X are critically involved in spine elongation (Hotulainen et al., 2009). Regulation of cofilin phosphorylation by various protein kinases and phosphatases would then be used to replenish the pool of G-actin in the spine, and to control the length of the actin filaments in both the spine neck and the spine head.

Another critical element in synapse formation involves the family of ephrin molecules (Hruska and Dalva, 2012). Again, some of the ephrin molecules interact with actin filaments through activation of Rac (Segura et al., 2007), thus linking extracellular events to actin polymerization and spine formation. Drebrin is an actin filament binding protein, which is required to cluster actin filaments at postsynaptic sites (Sekino et al., 2007). Interestingly, while drebrin A is localized in membranes in neonatal spines, it is mostly found in the cytoplasm of adult spines and its amount correlates with spine head size (Kobayashi et al., 2007). It has been proposed that drebrin is involved in synapse formation and in activity-dependent synaptic targeting of NMDA receptors (Takahashi et al., 2006). We have recently observed that drebrin is another calpain target (unpublished results), and this finding indicates the possibility that NMDA receptor-mediated calpain activation could directly affect actin polymerization through drebrin degradation.

Summary

Both axonal elongation and dendritic spine formation require actin filament regulation, and integration of extracellular signaling as well as regulation of local protein synthesis. Calpain participates in these processes by linking proteolysis to protein synthesis and regulation of actin filament assembly/disassembly.

4. General features of LTP

Synaptic transmission underlies every aspect of brain function, and neuronal plasticity is by and large due to the existence of synaptic plasticity. In general, synaptic plasticity refers to activity-dependent modifications of the strength of synaptic transmission. Such modifications may include changes in synapse number and strength. In 1973, Bliss and Lo made the important discovery that a brief high -frequency electrical stimulation of the perforant pathway in rabbit hippocampus produced a long-lasting enhancement in the strength of stimulated synapses to the dentate granule cells (Bliss and Lomo, 1973). This effect was later called long-term potentiation (LTP) of synaptic transmission. In the following years, LTP was also observed in the mossy fiber synapses in field CA3 and the Schaffer collateral synapses in field CA1, although LTP properties are not quite the same at these synapses (Harris and Cotman, 1986). It became rapidly apparent that several features of LTP made it an attractive cellular model for at least some forms of learning and memory. The best stimulation parameter to induce LTP at the Schaffer collateral synapses consists in short bursts of high frequency stimulation (generally at 100 Hz) repeated at frequencies closed to that of the theta rhythm (5–7 Hz) (theta burst stimulation (TBS) (Larson et al., 1986). Firing of large ensembles of neurons at theta frequency is generally assumed to occur physiologically when rodents are exploring new environments (Vanderwolf, 1969). LTP is also synapse specific, extremely long-lasting (up to several months in the intact animal), and pharmacological as well as genetic manipulations produce similar effects on LTP and on learning and memory (Baudry and Lynch, 2001). Another feature that makes LTP a good candidate for of memory mechanism is that it is initially unstable, as it can be disrupted by several electrophysiological (i.e., low frequency stimulation) or pharmacological manipulations during 30 min following TBS. After this initial period, LTP becomes increasingly resistant to disruption (Lynch et al., 2007b). Another interesting property of LTP for a memory mechanism was recently reported by the Lynch’s laboratory. Thus following one episode of TBS delivered to a set of Schaffer collaterals, there is a refractory period lasting about 1 h during which LTP cannot be further induced in the same population of synapses. After this refractory period, LTP can be further enhanced by repeated TBS (Kramar et al., 2012). This result might provide a cellular explanation for the beneficial effects of spaced trials over massed trials for learning.

LTP has been found mostly at glutamatergic synapses, although there are several reports that it could also be found at GABAergic synapses of the cerebellar cortex (Scelfo et al., 2008). There is a general consensus regarding the molecular events that are required for LTP induction, and activation of NMDA receptors is widely recognized as being a critical requirement for at least some forms of LTP (referred to as NMDA receptor-dependent LTP). There is also a general consensus for the end-point event that underlies the enhanced synaptic transmission at glutamatergic synapses. Thus, LTP-inducing stimuli delivered to the Schaffer collateral pathway result in an increased size of spines in CA1 dendrites with increased number of postsynaptic AMPA receptors (Baudry and Lynch, 2001; De Roo et al., 2008; Kessels and Malinow, 2009; Luscher and Malenka, 2012; Lynch et al., 2007b). What happens between the activation of NMDA receptors and the enlarged dendritic spines and increased number of AMPA receptors remains a source of continuous debate. Interestingly, TBS was found to be optimal for BDNF release from neuronal terminals (Lu, 2003; Lynch et al., 2007a; Pang et al., 2004; Rex et al., 2007; Thoenen, 2000; Yamada et al., 2002). BDNF plays several important roles in LTP-associated synaptic plasticity, such as inducing AMPA receptor translocation from the cytoplasm to the cell surface, increasing actin polymerization in dendritic spines, and enhancing local protein synthesis (Bramham, 2007; Chen et al., 2007; Jourdi et al., 2009; Narisawa-Saito et al., 2002; Rex et al., 2006; Rex et al., 2007). All these events have been linked to the induction and maintenance of long-term structural changes at synapses (Lynch and Baudry, 1984; Rex et al., 2007; Taniguchi et al., 2006; Tominaga-Yoshino et al., 2002; Yamamoto et al., 2005). More recently, the MAPK pathway has also been shown to play a central role in LTP formation, although the exact targets of this pathway have generally been assumed to be some elements of the transcriptional and/or translational machinery (Giovannini, 2006; Selcher et al., 2003; Shalin et al., 2006).

The calcium influx provided by rapid activation of the NMDA receptor channel activates a series of molecular cascades in postsynaptic cells leading to increased surface expression of AMPA receptor levels (Takahashi et al., 2003). We first proposed that increase in postsynaptic calcium concentration resulted in calpain activation (Lynch and Baudry, 1984). At the time we argued that calpain activation cleaved the cytoskeletal protein, spectrin, to allow for insertion of more glutamate receptors in postsynaptic membranes and to permit morphological changes in dendritic spines, which provided for a long lasting enhancement of synaptic efficacy, or LTP. In support of this hypothesis, LTP has been blocked by administration of calpain inhibitors (del Cerro et al., 1990; Denny et al., 1990; Oliver et al., 1989; Staubli et al., 1988) and by administration of antisense oligonucleotides to decrease calpain-1 levels in cultured hippocampal slices (Vanderklish et al., 1996). More recently, a calpain-4 (the small subunit common to both μ-calpain and m-calpain) conditional knock-out mouse was reported to have deficiency in LTP as well as in learning and memory (Amini et al., 2013). Moreover, down-regulation of m-calpain by injection of siRNA against m-calpain was also found to impair LTP and learning and memory (Zadran et al., 2012). As we will discussed below, this original and specific hypothesis has now been considerably expanded and recent findings have strengthened the theme of this review, i.e., that synaptic plasticity is an adaptation of the mechanisms involved in cell motility.

Summary

Long-term potentiation is a cellular model of learning and memory and results from activity-dependent modifications of the structure and function of dendritic spines, which depend on actin polymerization. Calpain activation is critical for LTP as it links NMDA receptor and BDNF receptor activation with regulation of actin filaments.

5. LTP: an adaptation of cell motility

5.1. Role of cytoskeleton regulation in LTP consolidation

While the events underlying LTP induction are now well understood, recent findings have indicated that actin polymerization plays a critical role in LTP consolidation. These findings have greatly extended ideas that were developed earlier regarding the potential functions of the actin cytoskeleton in dendritic spines (Crick, 1982; Halpain, 2000; Matus et al., 1982). LTP induction by theta burst stimulation (TBS) of the Schafer collateral pathway results in rapid actin polymerization in dendritic spines of CA pyramidal neurons (Kramar et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2005). Blocking actin polymerization with latrunculin applied shortly after TBS prevented LTP consolidation, but this effect was no longer present 10 min after TBS (Rex et al., 2009). Several intracellular cascades linking TBS to actin polymerization have been identified. The first one involves stimulation of NMDA receptors and the resulting influx of calcium, leading to activation of RhoA and Rac, presumably through the activation of GEFs and GAPs; thus this process is similar to what takes place in any cell type responding to extracellular signals by cytoskeleton modification and changes in cell motility. As discussed earlier, this pathway leads to activation of ROCK, followed by LIM kinase activation and coflin phosphorylation, resulting in actin polymerization and actin filament elongation. Inhibiting ROCK prevented LTP consolidation as well as TBS-induced increase in actin polymerization (Rex et al., 2009). A second pathway is triggered by BDNF release, a critical event in LTP induction and memory formation, and activation of the TrkB receptor; this pathway involves cdc42 and PAK activation, and it has been shown that FAK activation is the intermediate between BDNF and cdc42 (Myers et al., 2012). Thus, TBS by stimulating NMDA receptors and BDNF release triggers the same sequences of events, and involving the same intracellular cascades that are used by most cells undergoing changes in cell motility.

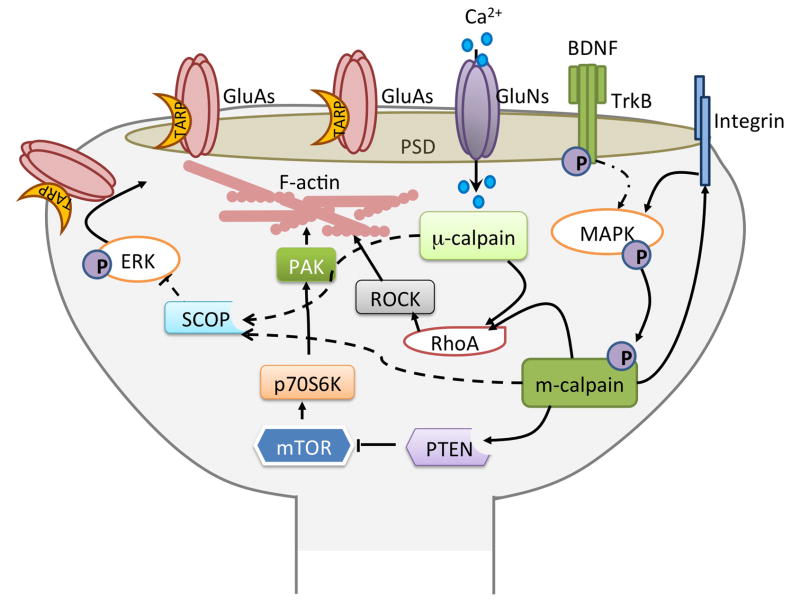

5.2. Role of calpain in cytoskeletal reorganization

Our original hypothesis postulated that calpain, by truncating the cytoskeletal spectrin, was important to initiate structural modifications of dendritic spines, and in particular to trigger the elongation of actin filaments. Taking into account the information collected over the last 25 years it is clear that calpain plays a more complex role in LTP and its associated structural reorganization of dendritic spines than what we originally proposed. Thus, we are proposing that the initial step for LTP induction requires the equivalent of a de-adhesion step, which would involve calpain-mediated degradation of FAK and integrins. Specifically, calpain degrades integrins and adaptor proteins needed for their activation and signaling (Du et al., 1995; Flevaris et al., 2007; Sawhney et al., 2006). This step could be rapid and account for the latrunculin effect observed during the first 10 min after TBS, but could also trigger over signaling cascades required for later stages of consolidation. We also propose that BDNF release would contribute to initiate later stages of m-calpain activation through ERK-mediated phosphorylation (Zadran et al., 2010). m-Calpain, by truncating PTEN, would then activate the mTOR pathway and sets in motion a series of downstream cascades, leading on one hand to further regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, and on the other hand, to stimulation of local protein synthesis (Fig. 3) (Briz et al., 2013).

Figure 3. Roles of calpain in synaptic plasticity.

While activation of NMDA receptor is required for the initiation of the changes leading to long-term potentiation, the detailed mechanisms involved in LTP consolidation and maintenance are still not completely understood. The schematic illustrates several cascades that are regulated by μ- or m-calpain. Calpain degrades RhoA and is thus linked to actin polymerization. Calpain also degrades suprachiasmatic nucleus [SCN] circadian oscillatory protein (SCOP), a negative ERK regulator (Shimizu et al., 2007), thereby regulating AMPA receptor exocytosis. m-Calpain activated by MAPK-mediated phosphorylation degrades PTEN leading to mTOR activation and increases in local protein synthesis. mTOR activation has also been shown to activate PAK and to regulate actin plolymerization. Thus, the concerted spatio-temporal integration of these different pathways is critical to determine the direction of synaptic plasticity.

The complex processes described in the preceding sections implicate several pathways that are likely to be engaged in both LTP induction and consolidation. It is therefore clear that the spatio-temporal concerted activation of these multiple pathways is the key regulatory process that determines the localization as well as the degree of synaptic modifications resulting from a particular set of experimental conditions. In this revised model, we maintain our original argument that calpain activation helps orchestrate the sequence and timing of signaling cascades that are involved in the assembly and then stabilization of newly formed actin filaments in the minutes following LTP induction (Fig. 3).

5.3. Links between actin polymerization and local protein synthesis

As mentioned above, incorporating calpain-mediated degradation of a number of proteins involved in the regulation of cell cytoskeleton with synaptic growth requires the existence of mechanisms linking cytoskeleton regulation and local protein synthesis regulation. We already discussed one of these mechanisms, which involves calpain-mediated PTEN truncation and mTOR activation, followed by stimulation of translation of locally present mRNAs. Recent findings have revealed the existence of additional bidirectional mechanisms linking extracellular signals to cytoskeletal modification and regulation of protein translation. Thus, FAK activation by extracellular signals has been shown to directly phosphorylate/activate mTOR and one of its downstream effectors, 70S6K, which in turn can directly phosphorylate and activate PAK, leading to actin remodeling (Gu et al., 2013). Activity-dependent cytoskeletal (Arc) protein, aka, Arg3.1, is another actin binding protein, whose transcription and translation are rapidly stimulated by activity. Thus, high-frequency stimulation and NMDA receptor activation produces rapid Arc transcription, targeting of Arc mRNA to activated dendrites, and Arc translation (Steward et al., 1998). Interestingly, these rapid events are mediated by activation of Rho kinase and actin polymerization, together with the activation of ERK (Huang et al., 2007). Finally, several miRNAs, including miR132, mir134 and miR138, have been shown to regulate actin cytoskeleton and to be present in dendritic spines (Fortin et al., 2012). Thus, activation of miR138 results in spine shrinkage whereas activation of miR132 and miR134 results in spine enlargement. Recently, calpain was shown to produce cleavage and subsequent activation of dicer, a rate-limiting endoribunuclease involved in the formation of miRNAs (Lugli et al., 2005). Dicer processes pre-miRNAs into miRNAs, which are then incorporated into RNA-induced silencing complexes (RISC) within or near dendritic spines. This pathway provides an additional mechanism linking calpain activation to regulation of actin cytoskeleton.

Summary

Synaptic plasticity is an adaptation of cell motility, as it involves the same complex machinery that regulates cell motility, and in particular actin filament polymerization/depolymerization. Calpain activation links synaptic activity to actin filament regulation and local protein synthesis.

6. Implications for learning and memory disorders

We recently discussed how the understanding of the molecular/cellular mechanisms of synaptic plasticity, and by extension of learning and memory, could help us understand the causes of learning and memory impairments observed in a wide range of human disorders (Baudry et al., 2011). In particular, we reviewed recent findings indicating that mental retardation associated with Fragile X syndrome could be accounted for by a failure of TBS to activate Rac and PAK (Chen et al., 2010). More generally, many psychiatric disorders, including autism, schizophrenia and mental retardation, are associated with mutations of genes coding for proteins involved in synapse formation and plasticity, and in cell motility regulation (Melom and Littleton, 2011).

The mTOR pathway is also deregulated in several disorders associated with intellectual disability, including Fragile X syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, mouse models of Down syndrome and Rett’s syndrome (Crino, 2011; Troca-Marin et al., 2012). Several mutations in TSC1, neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1), and PTEN, all upstream modulators of mTOR, lead to mTOR overactivation, and excessive local protein synthesis and alterations in actin cytoskeletom (Sawicka and Zukin, 2012). Therefore, it has been suggested that rapamycin could be a potential therapeutic treatment for these types of disorders (Ehninger and Silva, 2011).

In a rare neurological disorder, Lissencephaly, mutations in Lis1 result in brain malformation, mental retardation and seizure activity. The protein encoded by Lis1 is a non-catalytic subunit of platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase IB, and controls the dynamics of neuronal filopodia through interaction with dynein and the actin cytoskeleton. Mutations in Lis1 result in numerous spine alterations and abnormal organization of the cortical layers. As the protein encoded by Lis1 is a calpain substrate, it has been proposed that treatment with a calpain inhibitor could revert some of the symptoms of the disorder in heterozygous Lis+/− mice (Yamada et al., 2010), and recent results with a blood-brain barrier permeable calpain inhibitor confirmed these findings (Toba et al., 2013).

More generally, the notion that learning and memory is an adaptation of the mechanisms of cell motility accounts for the observations that mutations in a large number of genes result in an apparently similar phenotype, and in similar abnormalities in spine structure and in mechanisms of synaptic plasticity. This notion also suggests that it should be possible to find a small number of targets that could be used to reverse the learning disability associated with a wide range of psychiatric disorders.

Summary

Understanding the similarities between cell motility and synaptic plasticity provides new insight into the mechanisms underlying a number of neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders associated with learning and memory impairment.

7. Conclusion

Actin polymerization and increasingly complex mechanisms of cell motility were early events in life evolution, and were then used over and over by cells to perform a multitude of functions. With the apparition of neurons, the cellular mechanisms underlying cell motility were adapted to not only underlie neuronal migration, axonal elongation and spine formation, but also to produce rapid activity-dependent modifications of synaptic contacts, the cellular mechanism of synaptic plasticity and of learning and memory. The calpain family of calcium-dependent proteases also evolved early, and was incorporated in the mechanisms of cell motility as an ideal tool to integrate extracellular signals with a variety on intracellular cascades. We argued that calpains represent a major regulator of the complex cascades of events linking neuronal interactions with the extracellular milieu, local protein synthesis, and synaptic plasticity. This novel understanding of the mechanisms of synaptic plasticity provides a new framework to better understand a wide range of disorders associated with learning and memory impairment.

Highlights.

Cell motility and synaptic plasticity share many molecular components

Calpain plays critical roles in both cell motility and synaptic plasticity

Calpain provides the link between extracellular signals, actin cytoskeleton regulation and local protein synthesis

Synaptic plasticity is an adaptation of cell motility

This framework accounts for similar phenotypes observed in many learning and memory disorders

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants P01NS045260-01 from NINDS (PI: Dr. C.M. Gall), and grant R01NS057128 from NINDS to MB. XB is also supported by funds from the Daljit and Elaine Sarkaria Chair. We wish to thank Drs. G. Lynch and C. Gall for numerous discussions and ideas discussed in the review. We also want to acknowledge the work of all the students, postdocs and technicians who have worked in our laboratories over the years.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allard J, Mogilner A. Traveling waves in actin dynamics and cell motility. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:107–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amini M, Ma CL, Farazifard R, Zhu G, Zhang Y, Vanderluit J, et al. Conditional Disruption of Calpain in the CNS Alters Dendrite Morphology, Impairs LTP, and Promotes Neuronal Survival following Injury. J Neurosci. 2013;33:5773–5784. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4247-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspenstrom P. Integration of signalling pathways regulated by small GTPases and calcium. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1742:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry M, Lynch G. Remembrance of arguments past: how well is the glutamate receptor hypothesis of LTP holding up after 20 years? Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2001;76:284–97. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry M, Bi X, Gall C, Lynch G. The biochemistry of memory: The 26 year journey of a ‘new and specific hypothesis’. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;95:125–33. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear JE, Svitkina TM, Krause M, Schafer DA, Loureiro JJ, Strasser GA, et al. Antagonism between Ena/VASP proteins and actin filament capping regulates fibroblast motility. Cell. 2002;109:509–21. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfenati F. Synaptic plasticity and the neurobiology of learning and memory. Acta Biomed. 2007;78(Suppl 1):58–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlucchi G, Buchtel HA. Neuronal plasticity: historical roots and evolution of meaning. Exp Brain Res. 2009;192:307–19. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Lomo T. Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. J Physiol. 1973;232:331–56. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramham CR. Control of synaptic consolidation in the dentate gyrus: mechanisms, functions, and therapeutic implications. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:453–71. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briz V, Hsu YT, Li Y, Lee E, Bi X, Baudry M. Calpain-2-Mediated PTEN Degradation Contributes to BDNF-Induced Stimulation of Dendritic Protein Synthesis. J Neurosci. 2013;33:4317–28. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4907-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell RL, Davies PL. Structure-function relationships in calpains. Biochem J. 2012;447:335–51. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carragher NO, Frame MC. Calpain: a role in cell transformation and migration. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34:1539–43. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carragher NO, Westhoff MA, Fincham VJ, Schaller MD, Frame MC. A novel role for FAK as a protease-targeting adaptor protein: regulation by p42 ERK and Src. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1442–50. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00544-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LY, Rex CS, Casale MS, Gall CM, Lynch G. Changes in synaptic morphology accompany actin signaling during LTP. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5363–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0164-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LY, Rex CS, Babayan AH, Kramar EA, Lynch G, Gall CM, et al. Physiological activation of synaptic Rac>PAK (p-21 activated kinase) signaling is defective in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10977–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1077-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Kim S, Lee J, Ko SG, Lee W, Han IO, et al. The oligomeric status of syndecan-4 regulates syndecan-4 interaction with alpha-actinin. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;87:807–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick F. Do dendritic spines twitch? Trends in Neurosciences. 1982;5:44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Crino PB. mTOR: A pathogenic signaling pathway in developmental brain malformations. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:734–42. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Roo M, Klauser P, Garcia PM, Poglia L, Muller D. Spine dynamics and synapse remodeling during LTP and memory processes. Prog Brain Res. 2008;169:199–207. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Cerro S, Larson J, Oliver MW, Lynch G. Development of hippocampal long-term potentiation is reduced by recently introduced calpain inhibitors. Brain Res. 1990;530:91–5. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90660-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny JB, Polan-Curtain J, Ghuman A, Wayner MJ, Armstrong DL. Calpain inhibitors block long-term potentiation. Brain Res. 1990;534:317–20. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovanni S, Knights CD, Rao M, Yakovlev A, Beers J, Catania J, et al. The tumor suppressor protein p53 is required for neurite outgrowth and axon regeneration. EMBO J. 2006;25:4084–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson BJ. Rho GTPases in growth cone guidance. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:103–10. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez R, Holmes KC. Actin structure and function. Annu Rev Biophys. 2011;40:169–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X, Saido TC, Tsubuki S, Indig FE, Williams MJ, Ginsberg MH. Calpain cleavage of the cytoplasmic domain of the integrin beta 3 subunit. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26146–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudanova I, Klein R. Integration of guidance cues: parallel signaling and crosstalk. Trends Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehninger D, Silva AJ. Rapamycin for treating Tuberous sclerosis and Autism spectrum disorders. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emes RD, Pocklington AJ, Anderson CN, Bayes A, Collins MO, Vickers CA, et al. Evolutionary expansion and anatomical specialization of synapse proteome complexity. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:799–806. doi: 10.1038/nn.2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian Z, Vecsernyes M, Pap M, Szeberenyi J. The effects of a mutant p53 protein on the proliferation and differentiation of PC12 rat phaeochromocytoma cells. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:1431–41. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flevaris P, Stojanovic A, Gong H, Chishti A, Welch E, Du X. A molecular switch that controls cell spreading and retraction. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:553–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin DA, Srivastava T, Soderling TR. Structural modulation of dendritic spines during synaptic plasticity. Neuroscientist. 2012;18:326–41. doi: 10.1177/1073858411407206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox JE. On the role of calpain and Rho proteins in regulating integrin-induced signaling. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:385–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame MC, Fincham VJ, Carragher NO, Wyke JA. v-Src’s hold over actin and cell adhesions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:233–45. doi: 10.1038/nrm779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G. RhoA-kinase coordinates F-actin organization and myosin II activity during semaphorin-3A-induced axon retraction. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3413–23. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardel ML, Schneider IC, Aratyn-Schaus Y, Waterman CM. Mechanical integration of actin and adhesion dynamics in cell migration. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:315–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.011209.122036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannini MG. The role of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway in memory encoding. Rev Neurosci. 2006;17:619–34. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2006.17.6.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glading A, Uberall F, Keyse SM, Lauffenburger DA, Wells A. Membrane proximal ERK signaling is required for M-calpain activation downstream of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23341–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glading A, Bodnar RJ, Reynolds IJ, Shiraha H, Satish L, Potter DA, et al. Epidermal growth factor activates m-calpain (calpain II), at least in part, by extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mediated phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2499–512. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2499-2512.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez TM, Zheng JQ. The molecular basis for calcium-dependent axon pathfinding. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:115–25. doi: 10.1038/nrn1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S, Kounenidakis M, Schmidt EM, Deshpande D, Alkahtani S, Alarifi S, et al. Rapid activation of FAK/mTOR/p70S6K/PAK1-signaling controls the early testosterone-induced actin reorganization in colon cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2013;25:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpain S. Actin and the agile spine: how and why do dendritic spines dance? Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:141–6. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris EW, Cotman CW. Long-term potentiation of guinea pig mossy fiber responses is not blocked by N-methyl D-aspartate antagonists. Neurosci Lett. 1986;70:132–7. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotulainen P, Llano O, Smirnov S, Tanhuanpaa K, Faix J, Rivera C, et al. Defining mechanisms of actin polymerization and depolymerization during dendritic spine morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:323–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotulainen P, Hoogenraad CC. Actin in dendritic spines: connecting dynamics to function. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:619–29. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou ST, Jiang SX, Smith RA. Permissive and repulsive cues and signalling pathways of axonal outgrowth and regeneration. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2008;267:125–81. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(08)00603-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruska M, Dalva MB. Ephrin regulation of synapse formation, function and plasticity. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2012;50:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Chotiner JK, Steward O. Actin polymerization and ERK phosphorylation are required for Arc/Arg3.1 mRNA targeting to activated synaptic sites on dendrites. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9054–67. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2410-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher A, Palecek SP, Lu Q, Zhang W, Mellgren RL, Lauffenburger DA, et al. Regulation of cell migration by the calcium-dependent protease calpain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32719–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.32719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdi H, Hsu YT, Zhou M, Qin Q, Bi X, Baudry M. Positive AMPA receptor modulation rapidly stimulates BDNF release and increases dendritic mRNA translation. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8688–97. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6078-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels HW, Malinow R. Synaptic AMPA receptor plasticity and behavior. Neuron. 2009;61:340–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi C, Aoki C, Kojima N, Yamazaki H, Shirao T. Drebrin a content correlates with spine head size in the adult mouse cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2007;503:618–26. doi: 10.1002/cne.21408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramar EA, Lin B, Rex CS, Gall CM, Lynch G. Integrin-driven actin polymerization consolidates long-term potentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5579–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601354103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramar EA, Babayan AH, Gavin CF, Cox CD, Jafari M, Gall CM, et al. Synaptic evidence for the efficacy of spaced learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5121–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120700109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S, Saido TC, Suzuki K, Fox JE. Calpain mediates integrin-induced signaling at a point upstream of Rho family members. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21265–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S, Goll DE, Fox JE. Calpain cleaves RhoA generating a dominant-negative form that inhibits integrin-induced actin filament assembly and cell spreading. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24435–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203457200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Molli PR, Pakala SB, Bui Nguyen TM, Rayala SK, Kumar R. PAK thread from amoeba to mammals. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107:579–85. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson J, Wong D, Lynch G. Patterned stimulation at the theta frequency is optimal for the induction of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Brain Res. 1986;368:347–50. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levayer R, Lecuit T. Biomechanical regulation of contractility: spatial control and dynamics. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:61–81. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Kramar EA, Bi X, Brucher FA, Gall CM, Lynch G. Theta stimulation polymerizes actin in dendritic spines of hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2062–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4283-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Lu Y, Lee JK, Samara R, Willenberg R, Sears-Kraxberger I, et al. PTEN deletion enhances the regenerative ability of adult corticospinal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1075–81. doi: 10.1038/nn.2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohof AM, Quillan M, Dan Y, Poo MM. Asymmetric modulation of cytosolic cAMP activity induces growth cone turning. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1253–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-04-01253.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B. BDNF and activity-dependent synaptic modulation. Learn Mem. 2003;10:86–98. doi: 10.1101/lm.54603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugli G, Larson J, Martone ME, Jones Y, Smalheiser NR. Dicer and eIF2c are enriched at postsynaptic densities in adult mouse brain and are modified by neuronal activity in a calpain-dependent manner. J Neurochem. 2005;94:896–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher C, Malenka RC. NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation and long-term depression (LTP/LTD) Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012:4. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch G, Baudry M. The biochemistry of memory: a new and specific hypothesis. Science. 1984;224:1057–63. doi: 10.1126/science.6144182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch G, Kramar EA, Rex CS, Jia Y, Chappas D, Gall CM, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor restores synaptic plasticity in a knock-in mouse model of Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci. 2007a;27:4424–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5113-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch G, Rex CS, Gall CM. LTP consolidation: substrates, explanatory power, and functional significance. Neuropharmacology. 2007b;52:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machesky LM, Insall RH. Scar1 and the related Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein, WASP, regulate the actin cytoskeleton through the Arp2/3 complex. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1347–56. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)00015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattila PK, Lappalainen P. Filopodia: molecular architecture and cellular functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:446–54. doi: 10.1038/nrm2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matus A, Ackermann M, Pehling G, Byers HR, Fujiwara K. High actin concentrations in brain dendritic spines and postsynaptic densities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:7590–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melom JE, Littleton JT. Synapse development in health and disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:256–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelot A, Drubin DG. Building distinct actin filament networks in a common cytoplasm. Curr Biol. 2011;21:R560–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming GL, Song HJ, Berninger B, Holt CE, Tessier-Lavigne M, Poo MM. cAMP-dependent growth cone guidance by netrin-1. Neuron. 1997;19:1225–35. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers JP, Robles E, Ducharme-Smith A, Gomez TM. Focal adhesion kinase modulates Cdc42 activity downstream of positive and negative axon guidance cues. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:2918–29. doi: 10.1242/jcs.100107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narisawa-Saito M, Iwakura Y, Kawamura M, Araki K, Kozaki S, Takei N, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates surface expression of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazoleproprionic acid receptors by enhancing the N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor/GluR2 interaction in developing neocortical neurons. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40901–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202158200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning K, Drepper C, Valori CF, Ahsan M, Wyles M, Higginbottom A, et al. PTEN depletion rescues axonal growth defect and improves survival in SMN-deficient motor neurons. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:3159–68. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver MW, Baudry M, Lynch G. The protease inhibitor leupeptin interferes with the development of LTP in hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 1989;505:233–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palecek SP, Huttenlocher A, Horwitz AF, Lauffenburger DA. Physical and biochemical regulation of integrin release during rear detachment of migrating cells. J Cell Sci. 1998;111 ( Pt 7):929–40. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.7.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang PT, Teng HK, Zaitsev E, Woo NT, Sakata K, Zhen S, et al. Cleavage of proBDNF by tPA/plasmin is essential for long-term hippocampal plasticity. Science. 2004;306:487–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1100135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin BJ, Huttenlocher A. Calpain. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34:722–5. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard TD, Borisy GG. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 2003;112:453–65. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard TD, Cooper JA. Actin, a central player in cell shape and movement. Science. 2009;326:1208–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1175862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Q, Baudry M, Liao G, Noniyev A, Galeano J, Bi X. A novel function for p53: regulation of growth cone motility through interaction with Rho kinase. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5183–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0420-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Q, Liao G, Baudry M, Bi X. Cholesterol Perturbation in Mice Results in p53 Degradation and Axonal Pathology through p38 MAPK and Mdm2 Activation. PLoS One. 2010a doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009999. April 6th, journal.pone.0009999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Q, Liao G, Baudry M, Bi X. Role of calpain-mediated p53 truncation in semaphorin 3A-induced axonal growth regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010b;107:13883–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008652107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex CS, Lauterborn JC, Lin CY, Kramar EA, Rogers GA, Gall CM, et al. Restoration of long-term potentiation in middle-aged hippocampus after induction of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:677–85. doi: 10.1152/jn.00336.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex CS, Lin CY, Kramar EA, Chen LY, Gall CM, Lynch G. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes long-term potentiation-related cytoskeletal changes in adult hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3017–29. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4037-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex CS, Chen LY, Sharma A, Liu J, Babayan AH, Gall CM, et al. Different Rho GTPase-dependent signaling pathways initiate sequential steps in the consolidation of long-term potentiation. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:85–97. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200901084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles E, Huttenlocher A, Gomez TM. Filopodial calcium transients regulate growth cone motility and guidance through local activation of calpain. Neuron. 2003;38:597–609. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca-Cusachs P, Iskratsch T, Sheetz MP. Finding the weakest link: exploring integrin-mediated mechanical molecular pathways. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:3025–38. doi: 10.1242/jcs.095794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Wiedemann U, Stuurman N, Vale RD. Molecular requirements for actin-based lamella formation in Drosophila S2 cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:1079–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottner K, Stradal TE. Actin dynamics and turnover in cell motility. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:569–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Kawashima S. Calpain function in the modulation of signal transduction molecules. Biol Chem. 2001;382:743–51. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney RS, Cookson MM, Omar Y, Hauser J, Brattain MG. Integrin alpha2-mediated ERK and calpain activation play a critical role in cell adhesion and motility via focal adhesion kinase signaling: identification of a novel signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8497–510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicka K, Zukin RS. Dysregulation of mTOR signaling in neuropsychiatric disorders: therapeutic implications. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:305–6. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scelfo B, Sacchetti B, Strata P. Learning-related long-term potentiation of inhibitory synapses in the cerebellar cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:769–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706342105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura I, Essmann CL, Weinges S, Acker-Palmer A. Grb4 and GIT1 transduce ephrinB reverse signals modulating spine morphogenesis and synapse formation. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:301–10. doi: 10.1038/nn1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekino Y, Kojima N, Shirao T. Role of actin cytoskeleton in dendritic spine morphogenesis. Neurochem Int. 2007;51:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selcher JC, Weeber EJ, Christian J, Nekrasova T, Landreth GE, Sweatt JD. A role for ERK MAP kinase in physiologic temporal integration in hippocampal area CA1. Learn Mem. 2003;10:26–39. doi: 10.1101/lm.51103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalin SC, Hernandez CM, Dougherty MK, Morrison DK, Sweatt JD. Kinase suppressor of Ras1 compartmentalizes hippocampal signal transduction and subserves synaptic plasticity and memory formation. Neuron. 2006;50:765–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K, Phan T, Mansuy IM, Storm DR. Proteolytic degradation of SCOP in the hippocampus contributes to activation of MAP kinase and memory. Cell. 2007;128:1219–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanyon CA, Bernard O. LIM-kinase1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;31:389–94. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staubli U, Larson J, Thibault O, Baudry M, Lynch G. Chronic administration of a thiol-proteinase inhibitor blocks long-term potentiation of synaptic responses. Brain Res. 1988;444:153–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90922-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O, Wallace CS, Lyford GL, Worley PF. Synaptic activation causes the mRNA for the IEG Arc to localize selectively near activated postsynaptic sites on dendrites. Neuron. 1998;21:741–51. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter DM, Miller KE. The emerging role of forces in axonal elongation. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;94:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Mizui T, Shirao T. Down-regulation of drebrin A expression suppresses synaptic targeting of NMDA receptors in developing hippocampal neurones. J Neurochem. 2006;97(Suppl 1):110–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Svoboda K, Malinow R. Experience strengthening transmission by driving AMPA receptors into synapses. Science. 2003;299:1585–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1079886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura M, Gu J, Danen EH, Takino T, Miyamoto S, Yamada KM. PTEN interactions with focal adhesion kinase and suppression of the extracellular matrix-dependent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt cell survival pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20693–703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi N, Shinoda Y, Takei N, Nawa H, Ogura A, Tominaga-Yoshino K. Possible involvement of BDNF release in long-lasting synapse formation induced by repetitive PKA activation. Neurosci Lett. 2006;406:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoenen H. Neurotrophins and activity-dependent plasticity. Prog Brain Res. 2000;128:183–91. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)28016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To KC, Church J, O’Connor TP. Combined activation of calpain and calcineurin during ligand-induced growth cone collapse. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;36:425–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toba S, Tamura Y, Kumamoto K, Yamada M, Takao K, Hattori S, et al. Post-natal treatment by a blood-brain-barrier permeable calpain inhibitor, SNJ1945 rescued defective function in lissencephaly. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1224. doi: 10.1038/srep01224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga-Yoshino K, Kondo S, Tamotsu S, Ogura A. Repetitive activation of protein kinase A induces slow and persistent potentiation associated with synaptogenesis in cultured hippocampus. Neurosci Res. 2002;44:357–67. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troca-Marin JA, Alves-Sampaio A, Montesinos ML. Deregulated mTOR-mediated translation in intellectual disability. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;96:268–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderklish P, Bednarski E, Lynch G. Translational suppression of calpain blocks long-term potentiation. Learn Mem. 1996;3:209–17. doi: 10.1101/lm.3.2-3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwolf CH. Hippocampal electrical activity and voluntary movement in the rat. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1969;26:407–18. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(69)90092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitriol EA, Zheng JQ. Growth cone travel in space and time: the cellular ensemble of cytoskeleton, adhesion, and membrane. Neuron. 2012;73:1068–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Mizuno M, Nabeshima T. Role for brain-derived neurotrophic factor in learning and memory. Life Sci. 2002;70:735–44. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01461-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Hirotsune S, Wynshaw-Boris A. A novel strategy for therapeutic intervention for the genetic disease: preventing proteolytic cleavage using small chemical compound. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1401–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Urakubo T, Tominaga-Yoshino K, Ogura A. Long-lasting synapse formation in cultured rat hippocampal neurons after repeated PKA activation. Brain Res. 2005;1042:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadran S, Jourdi H, Rostamiani K, Qin Q, Bi X, Baudry M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and epidermal growth factor activate neuronal m-calpain via mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2010;30:1086–95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5120-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadran S, Akopian G, Zadran H, Walsh J, Baudry M. RVG-Mediated Calpain2 Gene Silencing in the Brain Impairs Learning and Memory. Neuromolecular Med. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s12017-012-8196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Yan W, Chen X. p53 is required for nerve growth factor-mediated differentiation of PC12 cells via regulation of TrkA levels. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:2118–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XF, Schaefer AW, Burnette DT, Schoonderwoert VT, Forscher P. Rho-dependent contractile responses in the neuronal growth cone are independent of classical peripheral retrograde actin flow. Neuron. 2003;40:931–44. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng JQ, Poo MM. Calcium signaling in neuronal motility. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:375–404. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]