Abstract

Background

This cross-cultural study was designed to examine cultural differences in empathy levels of first-year medical students.

Methods

A total of 257 students from the academic year 2010/11, 131 at Jimma University, Ethiopia, and 126 at the Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, Germany, completed the Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES), the Reading the Mind in the Eyes (RME-R) test, and a questionnaire on sociodemographic and cultural characteristics. Furthermore, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the students' personal views on the definition of empathy and possible influencing factors. Group comparisons and correlation analyses of empathy scores were performed for the entire cohort and for the Jimma and Munich students separately. We used a regression tree analysis to identify factors influencing the BEES.

Results

The male students in Jimma (39.1 ± 22.3) scored significantly higher in the BEES than those male students from Munich (27.2 ± 22.6; p = 0.0002). There was no significant difference between the female groups. We found a moderate, positive correlation between the BEES and RME-R test, i.e. between emotional and cognitive empathy, within each university. Nevertheless, the RME-R test, which shows only Caucasian eyes, appears not to be suitable for use in other cultures.

Conclusions

The main findings of our study were the influence of culture, religion, specialization choice, and gender on emotional empathy (assessed with the BEES) and cognitive empathy (assessed with the RME-R test) in first-year medical students. Further research is required into the nature of empathy in worldwide medical curricula.

Keywords: Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale, Cross-cultural, Empathy, Medical Students

Introduction

Empathy in medical students was measured for the first time in 1977 in Australia (1). Since then, numerous studies have investigated empathy at medical schools all over the world (for an overview see (2–8)), although so far not in Africa. The main findings of the studies were a decline in empathy during medical school (3–5, 9–15), a higher empathy level in females than in males (4;5;7;9;12;14–19), and a relationship between the students' choice of future medical specialization and their empathy level scores (4, 15, 19, 20).

So far, no comparative study on empathy has been performed that considered possible effects on medical students' empathy of culture or other factors such as sociodemographic and personal characteristics. For example, the extent of students' religiousness might influence their empathetic and pro-social behavior (21) and thus also should be taken into account.

There is a general consensus that empathy is crucial to the physician-patient relationship and thus an important part of medical education (22): Being an empathetic doctor improves the patient's confidence (23), compliance (24), and satisfaction in the physician-patient relationship (25). Empathy represents the “touch” in modern medicine, which has a somewhat bad reputation as being “high tech, low touch” (26). The theoretical constructs of empathy are complex, and the appropriate empathy level for physicians, therefore, is still under discussion. Jodi Halpern suggested an answer to the question “What is clinical empathy?” (27). She wrote that physicians should focus on paying attention to the patient and do not have to experience vicariously their patients' emotions. Empathy originates from the German word “Einfühlung,” meaning the “feeling within” a person (28). Up to now, most authors divide empathy into emotional/vicarious and cognitive empathy, alluding to the discussion in cognitive science about the simulation theory, which proposes that a physician identifies with a patient (emotional empathy), versus the theory theory, which describes the quality of the “as if” condition (cognitive empathy).

Like Newton did in his study on changes in empathy during medical school (15), we chose to use the self-reported Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES) (29) to assess “heart-reading,” i.e. emotional empathy in the present study.

Gaze perception plays a crucial role in an individual's ability to reason about the intentions and feelings of others (30). The Reading the Mind in the Eyes test (RME-R test) (31) is an intuitive measurement that assesses the participants' ability to identify emotions from photographs of eye regions and does not allow them to answer in a socially desirable manner. For this reason, we used this test to evaluate “mind-reading,” i.e. cognitive empathy, rather than the test most commonly used in previous studies, the self-reported Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (33). The RME-R test has become a useful instrument for studying the neurobiological substrates of social and emotional skills (32).

In addition to the above scales, we developed a 20-item questionnaire (on ethnicity, relationships, religion, etc.) to investigate possible sociodemographic factors that influence empathy. Our analysis was motivated by the following research hypotheses:

Empathy is an innate and universal feeling, so medical students in different countries can be expected to show similar levels of empathy.

The sociodemographic background of medical students influences their empathy level.

Methods and Materials

Participants: The data for the study were gathered in two medical schools: The Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU), Germany, and Jimma University (JU), Ethiopia.

Munich is a city with approximately 1.4 million inhabitants, located in southern Germany. The Ludwig Maximilian University (LMU) had about 4,500 medical students altogether, about 900 of whom were first-year students. Jimma is a town in Ethiopia located 350 km southwest of the capital, Addis Ababa. Jimma University (JU) had about 1,000 medical students in total, including 200–220 first-year students. The two universities have different selection criteria for their medical students: While students applying to JU have to take an entrance examination, LMU students are selected predominantly on the basis of their high school grades. These two medical schools were chosen for this study because in 2002 the LMU and JU established cooperation with the objective of improving medical training and education in Jimma and Munich.

Assuming small to medium effect sizes (Cohen's d=0.4) and a power of 80%, we estimated that a sample size of 100 students per university would be required. In the end, a total of 257 first-year medical students from the academic year 2010/11 participated, 131 (16 [12%] women, 115 [88%] men) from JU and 126 (36 [29%] women, 90 [71%] men) from the LMU.

Survey instruments: We used two different survey instruments to measure the students' empathy levels: the 30-item Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES) (29) and the revised 36item version of the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RME-R test) (31).

The BEES is a reliable and valid instrument (34) consisting of 15 positively and 15 negatively worded items that measure emotional responses to fictitious situations and particular life events. It evaluates the extent to which the respondent is able to feel another's suffering or take pleasure in their happiness. Study subjects report the degree of their agreement or disagreement with each of the 30 items on a 9-point Likert scale. A higher total score represents a higher level of emotional empathy. The stated norms provided in the BEES manual (29) are 29 ± 28 for men and 60 ± 21 for women.

The RME-R test consists of 36 photographs depicting only the eye region of Caucasian individuals. A rectangular area of approximately 5 × 2 inches delineates the eye region, encompassing the entire width of the face from midway up the nose to right above the brow. Four mental states accompanying each stimulus (one target word and three foils) are presented at each corner of the high-resolution photograph. Both the Jimma and Munich students were given the English version of the RME-R test. English is the second official language in Ethiopia and is taught from primary school onward. To reduce linguistic difficulties, the test had a detailed glossary appended that explained all adjectives by using synonyms and example sentences. The stated norms for general population controls for the RME-T test are 26.0 ± 4.2 for male and 26.4 ± 3.2 for female adults (31). The advantage of the RME-R test over other methods for measuring cognitive empathy (35–37) is the non-verbal structure of the test, which reduces suggestibility and decreases the risk that participants might try to meet social expectations when answering.

The questionnaire on sociodemographic characteristics included questions on gender, age, university, ethnicity, country of birth, migration background, the people with whom the students grew up (mother/father/both/other), number of siblings, position among siblings (eldest/middle/youngest), major life events during childhood (divorce/illness/death of parents), place of residence (at home with relatives/moved out), parents' socio-economic status, active membership in a religious community, number of close relationships, involvement in a social network like Facebook, daily internet use, interest in a medical specialization (specialization with continuity of patient care such as internal medicine, psychiatry, or paediatrics versus specialization with less interpersonal contact such as surgery, radiology, or pathology) and a question on the students' personal experience with psychiatric or psychotherapeutic treatment. The influence of the different curricula on the students' empathy, including a comparison of first-and last-year medical students, is presented elsewhere (Dehning et al., in preparation).

In addition to the quantitative measurements, we conducted a qualitative analysis by using an “empathy interview” regarding the students' personal views on the definition of empathy and the correlation between empathy and a number of possible influencing factors (religion, number of siblings, etc.).

Procedures: The ethics committee of the LMU and the Ethical Clearance Board of JU approved the study.

The assessments were completed by the first-year medical students in Jimma in December 2010; and by the students in Munich, in February 2011.

Participation in the study was voluntary. The principal investigators explained the assessments to the students and remained with them while they completed the questionnaires to clarify possible questions. Students took about 25 minutes to complete the questionnaires. In addition, 10 students at each university were randomly selected for a qualitative interview, which was recorded and transcribed later.

Statistical analyses: In case of missing values in the BEES, the individual mean of the observed items for either the positively and negatively worded items was used, as long as no more than 5 of the 15 values in each category were missing. Otherwise, the questionnaire was treated as incomplete and excluded from the analyses. In the RME-R test, missing answers were interpreted as “the participant did not recognize the emotion.” However, completion of less than half of the RME-R questionnaire was interpreted as insufficient motivation to complete the test, and the questionnaire was excluded from the analyses.

The descriptive statistics are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Associations between sociodemographic factors and the BEES and RME-R were evaluated by Welch's t test and F tests (type II, two-way ANOVA), respectively. Because of the importance of gender in interpreting the test results and the small number of female students in our study, the analyses were only performed on the male subsample. Pearson correlations between the BEES and the RME-R were calculated. A p value below 0.05 was considered significant.

A regression tree was estimated (38) to identify sociodemographic characteristics that influence emotional empathy as measured by the BEES. In this inferential approach, the study population is recursively partitioned into subsets resulting from binary splits, each according to the input variable with the strongest association with the response variable. This hierarchical approach also enables the identification of interactions between variables, e.g. different background factors for Jimma and Munich. In this analysis, associations were evaluated with permutation tests and a univariate significance level of 5%, and splits were only allowed when each of the resulting subsets contains at least 10 respondents. All analyses were performed with the statistical software environment R 2.11.1 (39).

Results

Most items of the questionnaires were filled out according to the authors' instructions (29, 31). Some items were non-systematically missing in the BEES of 25 students from JU and 10 students from the LMU; these items were imputed by the respective student's item mean. One Jimma University students had to be excluded from BEES-related analyses because too many BEES items were missing; and one, because some data were invalid. For the RME-R-related analyses, two Jimma students had to be excluded because too many responses were missing.

Sociodemographic characteristics: A total of 257 first-year medical students participated in the study, 131 (16 women, 115 men) from JU and 126 (36 women, 90 men) from LMU. The Jimma students had a mean age of 19.3 years; the Munich students were slightly older, with a mean age of 21.0 years. Two ethnicities which dominated among the Jimma students: 37% were Amharic; and 41%, Oromo. The remaining students were from a variety of other ethnicities. In Munich, 95% of the students described themselves as Caucasians, and 13% of the students had a migration background (in Jimma, this was the case for only one student). In Jimma, 42% of the students had moved out of the family home, whereas 75% of the Munich students had moved out. A high proportion of the students had grown up with both parents: 82% in Jimma and 90% in Munich. The median number of siblings was 5 in Jimma and 1 in Munich. In Munich, 78% of the students described themselves as Christians, 21% did not state that they were members of a religious group, and 32% claimed to be actively practicing their religion. In Jimma, 77% of the students were Christians and 21% Muslims, and 74% practiced their religion actively. Regarding the specialization choice, 59% of the students from Jimma declared being interested in a specialty with continuity of patient care compared to 41% of the students in Munich (p=0.006).

In Munich, 53% of the students had at least five close relationships and no-one declared having none. In Jimma, only 18% of the students had at least five close relationships, and 9% had none. As regards social networking, e.g. Facebook, 90% of the LMU students participated but only 40% of those at JU.

The Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale: The JU male students scored significantly higher on the BEES (39.1 ± 22.3) than the LMU male students (27.2 ± 22.6; p=0.002). Thus, the scores of the Munich students were comparable to the male norm of 29, whereas those of the Jimma students were significantly higher (p<0.0001). BEES scores did not differ significantly between the two female groups (p=0.94). The female students from both JU (51.8 ± 30.6) and LMU (51.1 ± 17.1) had mean empathy scores below the female norm of 60. However, the common finding that women score higher in emotional empathy than men was confirmed for both JU and LMU, and the difference was statistically significant in both locations (p<0.0001, F test, two-way ANOVA).In Jimma, the BEES score of the male students was significantly associated with the students' activity in a religious community (p=0.022): actively religious students had higher BEES total scores (mean=42.6) than non-active students (31.0). The analysis showed also a significant association between specialization choice and empathy scores in Munich (p=0.014): students who preferred continuity of patient care had higher BEES scores (mean=33.3) than those preferring less interpersonal contact (18.9). No evidence for such an association was found among the JU students (p=0.94).

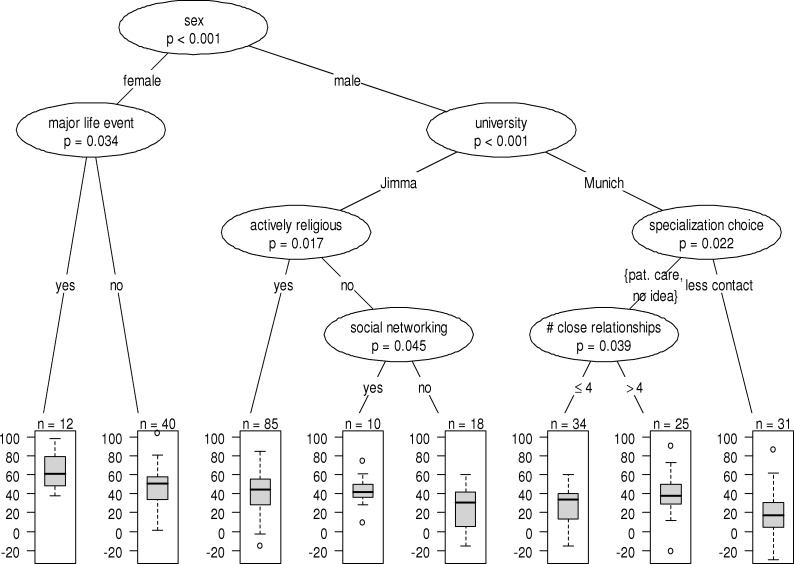

The regression tree showing the association of empathy scores with sociodemographic characteristics is presented in Figure 1. The most important distinction concerning the BEES score was between male and female students: female students who had experienced a major life event had higher empathy levels. Male students differed most according to the university they belonged to: In Jimma, active religiousness and involvement in social networking were significantly associated with higher BEES scores; in Munich, important characteristics associated with empathy levels were the specialization choice (less interpersonal contact related to lower empathy) and the number of close relationships (more relationships related to higher empathy).

Figure 1.

Regression tree for the Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES) on the basis of sociodemographic and cultural characteristics. Here, a p value corresponds to a permutation test on differences in the BEES with respect to the conducted binary split. The boxplots show the distributions of the BEES in the subgroups resulting from the recursive partitioning.

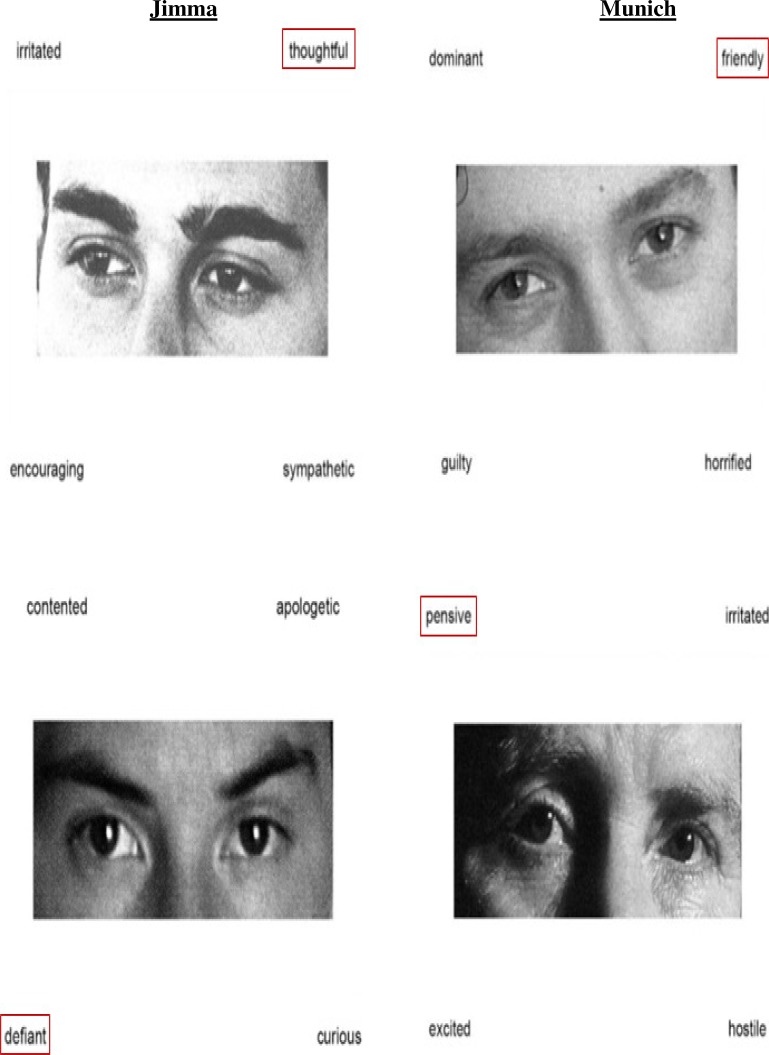

The Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test: The analyses of the RME-R test revealed significant differences between the two universities, with students from Munich scoring significantly higher (p<0.0001). On average, Jimma students assigned the correct mental state to 14.4 (males: 14.1, females: 16.3) of the 36 photographs; Munich students were able to assign 22.0 (males: 21.6, females: 23.1) photographs correctly. The difference between Jimma and Munich students was significant for both males and females (p<0.0001). The mean scores of the male and female students in Jimma were lower than those stated above (26.0 ± 4.2 for males, 26.4 ± 3.2 for females) (31), and females generally scored higher than their fellow male students (p=0.015, F test). The emotions most often correctly identified by males were “friendly” in Munich (by 92% of male students) and “thoughtful” in Jimma (60.2%); the least commonly identified emotions were “pensive” in Munich (25.6%) and “defiant” in Jimma (15.9%) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Emotions identified correctly most and least often by first-year medical students in Jimma and Munich in the Reading the Mind in the Eyes test

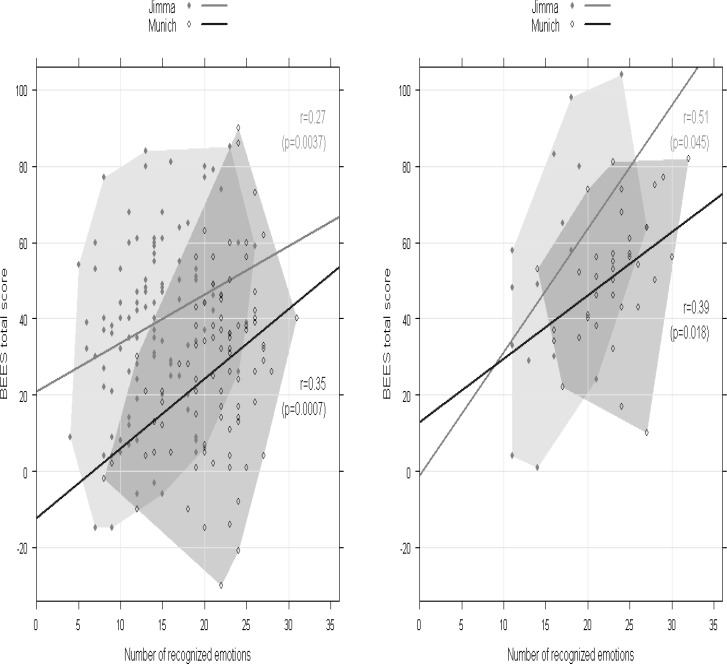

Within the universities, we found a moderate, positive correlation between the BEES scores and performance in the RME-R test, i.e. between emotional and cognitive empathy. This correlation was statistically significant (p<0.05) for both males and females at JU (male: r=0.27, female: r=0.51) and LMU (male: r=0.35, female: r=0.39,); see Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Correlation between emotional (Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale; BEES) and cognitive empathy (Reading the Mind in the Eyes test; RME-R test) in first-year medical students in Jimma and Munich; left: male, right: female

Discussion

Contrary to the initial hypothesis that empathy is an innate and universal feeling that is not influenced by ethnicity or culture, male Ethiopian students had significantly higher BEES scores than their counterparts in Munich. The students interviewed for the qualitative analysis had different opinions on this topic. Here are some excerpts:

“There is more empathy in Ethiopia. What I know from films and movies, the people in Europe are more or less selfish. The interpersonal competition is so high, and the people are so busy doing their things, they have no time. Everyone lives his own life.” (male, 19 years, Jimma)

“Empathy is stronger in Germany. The low standard of our living conditions makes the people in Ethiopia feel risky. When poverty dominates their mind, they lack the ability to feel for others,” (male, 20 years, Jimma)

“I think regional provenance has nothing to do with empathy. There are empathetic people all over the world,” (male, 22 years, Munich).

What could be the possible causes for the comparatively low BEES scores in Munich? One possible factor could be the higher numbers of students in Munich than in Jimma: There are about four to five times more medical students at LMU than at JU. Large numbers of students might increase competition between the students and reinforce anonymity, which in turn could cause a decrease in empathy and increase in egoism (40). Similarly, in the “Hardening of the Heart” study performed in Arkansas, the classes with a low number of students (about 100 per year) had higher BEES scores than the Munich students (male freshman mean score: 37.87) (15).

The fact that more JU students preferred a continuity of patient care (59%) than LMU students (41%) also could be discussed in line with the different BEES scores: Higher BEES scores can easily be connected with the idea of closer physician-patient contact. However, one must consider that JU students might have a smaller choice of specialization alternatives, particularly those with low patient contact, because of the lack of technical equipment. This fact might explain the necessity for “low tech-high touch” in Jimma.

The content of the BEES items is certainly culturally tuned, as some emotional behaviour might be more acceptable among males in Ethiopia than in Germany and vice versa. In Ethiopia, for example, young males commonly have closer physical contact in terms of walking hand-in-hand in public, hugging, and putting food in each other's mouths. Particular items of the BEES such as “Unhappy movie endings haunt me for hours afterward” or “I cannot feel much sorrow for those who are responsible for their misery” reflect the focus of the test on emotionality and the potentially resultant divergence of different cultures.

Can the different BEES levels between the male medical students in Jimma and Munich be explained also in part by the cultural differences? Several partly surprising main findings in studies on empathy in medical school in different countries suggest that empathy is influenced by cultural aspects. For example, empathy scores increased in a Japanese medical school (12) over the years, possibly due to the early inclusion of studies in the humanities and arts in medical education, which is not the case in other countries. A study in Korea (7) found no gender difference, no decline in empathy during medical school, and poor empathy scores in first-year medical students; the last finding was attributed to the paternalistic role expected in the physician-patient relationship. Rahimi-Madiseh et al. (6) explained that low empathy scores among Iranian medical students are due to Iranian patients' desire to be treated by doctors rather than having doctors empathizing with their emotions. Moreover, Iranian medical schools do not include courses in communication skills in the curriculum; the education system is very traditional and highly-structured, and lecture theatres often are very crowded.

Considering the high BEES scores in Jimma, the results of the RME-R test among Ethiopian students are surprisingly low: The JU students identified the emotions correctly in a mean of 14.4 of the 36 photographs, i.e. a 40% success rate, which is well below the general average noted for the RME-R test (26.0 ± 4.2 for male adults; 26.4 ± 3.2 for female adults). Nevertheless, the positive correlation between the BEES and RME-R test confirms that the RME-R test is suitable for measuring cognitive empathy. However, a limited comparability between different cultures is still very likely: The RME-R test uses pictures showing Caucasian eyes, which might be more difficult to read for non-Caucasians. People tend to ascribe more complex mental states to members of their own than to those of other social groups (41). The question of the influence of culture on the ability to read emotions in someone's eyes as a possible cause for the findings in this study are discussed in detail elsewhere (Gasperi, Dehning et al., submitted).

Our findings suggest that empathy in medical school is influenced not only by culture but also by sociodemographic characteristics, which confirms our second hypothesis. Significant associations were found between empathy and active religiousness in Jimma and between empathy and future medical specialization in Munich. As humanism, altruism, and charity are fundamental to religions, the relation between religiously more active Jimma students and empathy is obvious (21). As to the influence of religion on empathy, the opinion among the students was divided: “Religion encourages empathy in itself.” (male, 20 years, Jimma); “Religion and empathy are entirely unrelated.” (female, 23 years, Munich). Furthermore, there is some evidence for an association between empathy and the number of close relationships as well as the number of major life events experienced. No association was found with the other sociodemographic characteristics. One cannot dismiss that the scores may have differed between Jimma and Munich because of a differential suitability of the measurement tools in the two cultures.

The main findings of our study were the influence of culture, religion, specialization choice, and gender on emotional and cognitive empathy scores in the BEES and RME-R test among first-year medical students in Jimma, Ethiopia, and Munich, Germany. However, the kind of empathy required in medical students and future physicians may not necessarily be represented properly in the scales used in this study. Further research should be directed towards the nature of empathy in worldwide medical curricula.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ayalkibet Jiru, Desta Thushune, Hailemarian Hailesilasiie, and Kenfe Tesfaye for general support in Jimma, and Bianka Leitner, Fabian Jacobs, Florian Boss, Florian Seemüller, Josef Christan, Karin Koelbert, Laurenz Wurzinger, Michael Meyer, Nico Kühner, Paula Messner, Richi Musil, and Thomas Ludwig for general support in Munich. Special thanks go to the first-year medical students in Jimma and Munich! We thank also Jacquie Klesing, ELS, for editing assistance with the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hornblow AR, Kidson MA, Jones KV. Measuring medical students' empathy: a validation study. Med Educ. 1977 Jan;11(1):7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1977.tb00553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pedersen R. Empirical research on empathy in medicine-A critical review. Patient Educ Couns. 2009 Sep;76(3):307–322. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen DC, Pahilan ME, Orlander JD. Comparing a self-administered measure of empathy with observed behavior among medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2010 Mar;25(3):200–202. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1193-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, Brainard G, Herrine SK, Isenberg GA, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med. 2009 Sep;84(9):1182–1191. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b17e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nunes P, Williams S, Sa B, Stevenson K. A study of empathy decline in students from five health disciplines during their first year of training. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahimi-Madiseh M, Tavakol M, Dennick R, Nasiri J. Empathy in Iranian medical students: A preliminary psychometric analysis and differences by gender and year of medical school. Med Teach. 2010;32(11):e471–e478. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.509419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roh MS, Hahm BJ, Lee DH, Suh DH. Evaluation of empathy among Korean medical students: a cross-sectional study using the Korean Version of the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy. Teach Learn Med. 2010 Jul;22(3):167–171. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2010.488191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Todres M, Tsimtsiou Z, Stephenson A, Jones R. The emotional intelligence of medical students: an exploratory cross-sectional study. Med Teach. 2010 Jan;32(1):e42–e48. doi: 10.3109/01421590903199668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen D, Lew R, Hershman W, Orlander J. A cross-sectional measurement of medical student empathy. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Oct;22(10):143–148. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0298-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diseker RA, Michielutte R. An analysis of empathy in medical students before and following clinical experience. J Med Educ. 1981 Dec;56(12):1004–1010. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, Rattner S, Erdmann JB, Gonnella JS, et al. An empirical study of decline in empathy in medical school. Med Educ. 2004 Sep;38(9):934–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kataoka HU, Koide N, Ochi K, Hojat M, Gonnella JS. Measurement of empathy among Japanese medical students: psychometrics and score differences by gender and level of medical education. Acad Med. 2009 Sep;84(9):1192–1197. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b180d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kliszcz J, Hebanowski M, Rembowski J. [Level and dynamics of empathy in I and VI year students at the Medical Academy of Medicine in Gdansk] Pol Tyg Lek. 1996 Jan;51(1–5):55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kliszcz J, Hebanowski M, Rembowski J. Emotional and cognitive empathy in medical schools. Acad Med. 1998 May;73(5):541. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199805000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newton BW, Barber L, Clardy J, Cleveland E, O'Sullivan P. Is there hardening of the heart during medical school? Acad Med. 2008 Mar;83(3):244–249. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181637837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Austin EJ, Evans P, Magnus B, O'Hanlon K. A preliminary study of empathy, emotional intelligence and examination performance in MBChB students. Med Educ. 2007 Jul;41(7):684–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernndez-Olano C, Montoya-Fernndez J, Salinas-Snchez AS. Impact of clinical interview training on the empathy level of medical students and medical residents. Med Teach. 2008;30(3):322–324. doi: 10.1080/01421590701802299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pawelczyk A, Pawelczyk T, Bielecki J. [Differences in medical specialty choice and in personality factors among female and male medical students] Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2007 Nov;23(137):363–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hojat M. Empathy in medical students as related to specialty interest, personality, and perceptions of mother and father. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39:1205–1215. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kliszcz J, Hebanowski M. [Studies on empathy in doctors and medical students] Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2001 Aug;11(62):154–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norenzayan A, Shariff AF. The origin and evolution of religious prosociality. Science. 2008 Oct 3;322(5898):58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1158757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mercer SW, Reynolds WJ. Empathy and quality of care. Br J Gen Pract. 2002 Oct;52 Suppl:S9–S12. S9–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kliszcz J, Nowicka-Sauer K, Trzeciak B, Nowak P, Sadowska A. Empathy in health care providers—validation study of the Polish version of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51:219–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisenthal S, Emery R, Lazare A, Udin H. “Adherence” and the negotiated approach to patienthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979 Apr;36(4):393–398. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780040035003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blatt B, LeLacheur SF, Galinsky AD, Simmens SJ, Greenberg L. Does perspective-taking increase patient satisfaction in medical encounters? Acad Med. 2010 Sep;85(9):1445–1452. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eae5ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Public Image Investigation. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Othopaedic Surgeons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halpern J. What is clinical empathy? J Gen Intern Med. 2003 Sep;18(8):670–674. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipps T. Einfühlung, Innere Nachahmung und Organempfindung. Archiv für gesamte Psychologie. 1903;1:465–519. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehrabian A. Manual for the Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES) 2000. (Available from Albert Mehrabian, 1130 Alta Mesa Road, Monterey, CA 93940) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baron-Cohen S. Mindblindness: an essay on autism and theory of mind. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Hill J, Raste Y, Plumb I. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: a study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001 Feb;42(2):241–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Domes G, Heinrichs M, Michel A, Berger C, Herpertz SC. Oxytocin improves “mind-reading” in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2007 Mar 15;61(6):731–733. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Di LM, Cicchetti A, Lo SA, Taroni F, Hojat M. The Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: preliminary psychometrics and group comparisons in Italian physicians. Acad Med. 2009 Sep;84(9):1198–1202. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b17b3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehrabian A. Relations Among Personality Scales of Aggression, Violence, and Empathy: Validation Evidence Bearing on the Risk of Eruptive Violence Scale. Aggressive Behavior. 1997;23:433–445. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. Catalogue of Selected Documents in Psychology. 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44(1):113–126. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hojat M. MSNT. The Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: development and preliminary psychometric data. Educ Psychol Meas. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hothorn T, Hornik K, Zeileis A. Unbiased recursive partitioning: A conditional inference framework. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2006;15(3):651–674. [Google Scholar]

- 39.R Development Core Team, author. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kasper S. Personal Communication. 2011 24-32011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paladino MP, Leyens JP. Differential Association of Uniquely and Non-Uniquely Human Emotions with the Ingroup and the Outgroup. Group Processes Intergroup Relations. 2002;5(2):105–117. [Google Scholar]