Abstract

The timing of neurotransmitter release from neurons can be modulated by many presynaptic mechanisms. The retina uses synaptic ribbons to mediate slow graded glutamate release from bipolar cells that carry photoreceptor inputs. However, many inhibitory amacrine cells, which modulate bipolar cell output, spike and do not have ribbons for graded release. Despite this, slow glutamate release from bipolar cells is modulated by slow GABAergic inputs that shorten the output of bipolar cells, changing the timing of visual signaling. The time course of light-evoked inhibition is slow due to a combination of receptor properties and prolonged neurotransmitter release. However, the light-evoked release of GABA requires activation of neurons upstream from the amacrine cells, so it is possible that prolonged release is due to slow amacrine cell activation, rather than slow inherent release properties of the amacrine cells. To test this idea, we directly activated primarily action potential-dependent amacrine cell inputs to bipolar cells with electrical stimulation. We found that the decay of GABAC receptor-mediated electrically evoked inhibitory currents was significantly longer than would be predicted by GABAC receptor kinetics, and GABA release, estimated by deconvolution analysis, was inherently slow. Release became more transient after increasing slow Ca2+ buffering or blocking prolonged L-type Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Our results suggest that GABAergic amacrine cells have a prolonged buildup of Ca2+ in their terminals that causes slow, asynchronous release. This could be a mechanism of matching the time course of amacrine cell inhibition to bipolar cell glutamate release.

Keywords: inhibition, retina, GABAC receptor, patch clamp, neurotransmitter release

retinal bipolar cells (BCs) are slow-potential, nonspiking neurons that release glutamate through a synaptic ribbon specialized to mediate prolonged neurotransmitter release. However, inhibitory amacrine cells (ACs) that modulate BC output are often spiking neurons (Bloomfield 1992; Taylor 1999). Spiking in ACs is important for enhancing inhibition, since blocking spiking with tetrodotoxin (TTX) significantly decreases the inhibitory surround of retinal neurons (Taylor 1999; Volgyi et al. 2002). However, at most central synapses spike-mediated neurotransmitter release is primarily synchronous, tightly coupled in time to the presynaptic stimulus, and dependent on brief, large Ca2+ increases near the site of vesicle release (Geppert et al. 1994; Kochubey and Schneggenburger 2011; Nishiki and Augustine 2004). If release from ACs was equally fast, we would expect inhibition to have little effect on the slow glutamate release from BCs.

In fact, many studies have found that inhibitory input from ACs makes the output of BCs more transient (Dong and Werblin 1998; Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b; Sagdullaev et al. 2006), suggesting AC input is slow enough to modify slow BC output. In agreement with this, previous experiments have shown that light-evoked neurotransmitter release from ACs is prolonged, lasting several hundred milliseconds past a single brief light stimulus (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b; Eggers et al. 2007). However, because light-evoked release from ACs also requires activation of and glutamate release from photoreceptors and BCs upstream of the ACs, any point in this pathway could cause the observed prolonged release. A few prior studies have directly observed prolonged GABA release from ACs onto GABAA receptors (R) on other ACs. GABA release between pairs of cultured chick ACs could be prolonged by slow Ca2+ signals, but only by a stimulus that was >50 ms (Borges et al. 1995; Gleason et al. 1994, 1993), suggesting that long depolarization of Ca2+ channels was necessary to achieve this prolonged release. Prolonged release of GABA was also observed between pairs of starburst ACs (Zheng et al. 2004), although again this was in response to a prolonged presynaptic AC stimulus (200–500 ms) and stimuli of shorter duration were not tested.

These results suggest that release from ACs could be a different type of release: inherently slow asynchronous release that depends on prolonged Ca2+ signals that may be farther from the sites of release (Cummings et al. 1996; Lu and Trussell 2000; Otsu et al. 2004) and uses distinct presynaptic mechanisms (Pang and Sudhof 2010). Although at some synapses prolonged asynchronous release becomes prevalent after multiple presynaptic stimuli (Awatramani et al. 2005; Cummings et al. 1996; Hefft and Jonas 2005; Kirischuk and Grantyn 2003; Lu and Trussell 2000; Otsu et al. 2004) and the amount of asynchronous release can vary between neurons (Hefft and Jonas 2005), it has not been shown after a single brief presynaptic stimulus. To determine if slow light-evoked inhibition in response to a single brief stimulus is mediated by asynchronous release, we have focused on the retinal rod pathway.

Rod photoreceptors sense dim light and release glutamate onto rod BCs (RBCs), which relay signals downstream in the retina. RBC glutamate release is modulated by inhibitory inputs from ACs. We have focused on the largest input to RBCs that is mediated by GABAergic AC input to GABACRs, a GABA-gated Cl− channel (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b; Euler and Wässle 1998; Shields et al. 2000). The time course of GABACR light-evoked currents is influenced both by the slow kinetics of GABACRs (Chang and Weiss 1999; Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b; Palmer 2006) and by the slow GABA release from GABAergic ACs (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b). The GABACR presents an ideal target to study the kinetics of neurotransmitter release, in contrast to the previous investigations of GABA release from ACs onto GABAARs (Borges et al. 1995; Gleason et al. 1993, 1994). The GABACR, unlike the GABAAR (MacDonald and Twyman 1992), does not desensitize in response to prolonged GABA activation (Chang and Weiss 1999), so GABACR-mediated currents should more accurately reflect the time course of GABA release. To test if AC release could be inherently slow, asynchronous release, we activated AC release directly and briefly by placing a stimulating electrode in the layer where AC processes are. In this study, we have found a unique example: the GABAergic retinal AC that uses prolonged GABA release as its primary mechanism of neurotransmitter release.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of retinal slices.

Animal protocols were approved by the University of Arizona Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. As described previously (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006a), C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME), ages 35–60 days, were euthanized using carbon dioxide, and the eyes were enucleated. The cornea and lens were removed, and the eyecup was incubated in cold extracellular solution (see Solutions and drugs) containing 800 U/ml hyaluronidase for 20 min. The retina was removed from the eyecup, trimmed approximately square, and mounted onto 0.45-μm nitrocellulose filter paper (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The filter paper was sliced into 250-μm-thick slices and mounted onto vacuum grease on glass coverslips after rotating 90°. All experiments were done in light-adapted conditions.

Solutions and drugs.

Extracellular solution used as a control bath and for dissection contained (in mM) 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 Mg2Cl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 20 glucose, 26 NaHCO3, and 2 CaCl2 and was bubbled with a mixture of 95%-5% O2-CO2. The intracellular solution in the recording pipette contained (in mM) 120 CsOH, 120 gluconic acid, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 10 tetraethylammonium (TEA)-Cl, 10 phosphocreatine-Na2, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.5 Na-GTP, and 50 μM Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and was adjusted to pH 7.2 with CsOH.

To isolate receptor types, 500 nM–1 μM strychnine was used to block glycine receptors, 20 μM SR95531 was used to block GABAARs, and 50 μM (1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid hydrate (TPMPA) was used to block GABACRs. 6-Cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX; 20 μM) was used to block AMPA/kainate receptors. TTX (500 nM; Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) was used to block voltage-gated Na+ channels. To block Ca2+ channels, 10 μM nifedipine was used to block L-type Ca2+ channels, 20 nM ω-conotoxin GVIA (Alomone Labs) was used to block N-type Ca2+ channels, and 100 μM CdCl was used to blocked all voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. To block Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR), 50 μM ryanodine (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was used. To increase intracellular Ca2+ buffering, 50 μM BAPTA-AM (Invitrogen) and 50 μM EGTA-AM (Invitrogen) were used. Antagonists were applied to the slice by a gravity-driven superfusion system (Cell Microcontrols, Norfolk, VA) at a rate of ∼1 ml/min. Unless otherwise indicated, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Electrically stimulated recordings.

Glass coverslips containing retinal slices were placed in a custom chamber. The preparation was heated to 32° by temperature-controlled thin-stage and in-line heaters (Cell Microcontrols). Whole cell patch recordings were made from RBCs from retinal slices as described previously (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b). RBCs were clamped at 0 mV, the reversal potential for currents mediated by nonselective cation channels. Electrodes with resistances of 5–7 MΩ were pulled from borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) using a P97 Flaming/Brown puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). Liquid junction potentials of 20 mV were corrected at the beginning of each recording. RBCs were identified and axon terminals located by briefly exciting the dye contained in the intracellular solution using a fluorescence microscope.

Electrically evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (eIPSCs) were recorded from RBCs. Responses were filtered using a 5-kHz 4-pole low-pass Bessel filter on an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and digitized at 10 kHz with a Digidata 1140A data acquisition system (Molecular Devices) and Clampex software (Molecular Devices).

The stimulating pipette, containing extracellular solution, was placed in the region of the RBC axon terminals in the inner plexiform layer (IPL), and a 1-ms, 4- to 20-μA stimulus was applied by an S48 stimulator (Grass, Warwick, RI) with an attached PSIU6 photoelectric isolation unit (Grass). The stimulating interval was 60 s. RBC morphology (Ghosh et al. 2004) was confirmed at the end of the recording with the use of an Intensilight fluorescence lamp and Digitalsight camera operated with Elements software (Nikon Instruments, Tokyo, Japan). Because the eIPSC amplitude was very sensitive to variations in the stimulus intensity and had the potential to run down if the stimulus was too high, for each BC we used a stimulus level that gave us a moderate amount of current and was a repeatable response.

Data analysis and statistics.

eIPSC traces from a given response condition were averaged using Clampfit (Molecular Devices), and the charge transfer (Q), peak amplitude, time to peak, and decay to 37% of the peak (D37) were measured in each condition. To calculate the release time course underlying eIPSCs, averaged traces of control GABACR-mediated and drug application conditions were analyzed in custom Matlab software.

Release functions were calculated by convolution analysis (Diamond and Jahr 1995) using the relationship

| (1) |

such that

| (2) |

where sIPSC(t) is the average spontaneous GABACR-mediated IPSC and F and F−1 represent the Fourier transform and inverse Fourier transform of the function, respectively. Briefly, software data processing occurred as follows: data were downsampled from 10 to 1 kHz and smoothed using a moving average filter (20 points). The software calculated vesicle release from current-time curves by performing deconvolution of the average RBC GABACR-mediated current evoked by a single vesicle release [sIPSC(t)], from a previous study (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b). The deconvolution was performed by dividing the fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the single vesicle release into the FFT of the electrically evoked response [eIPSC(t)] and again smoothed similarly to the initial current trace. The resulting release traces were further analyzed in Clampfit, similarly to the eIPSCs.

Paired Student's t-tests were used to compare values between conditions for the same cell. For each cell, a normalized data value of the percentage of total GABACR-mediated eIPSC that remained after the drug treatment was calculated. Regular Student's t-tests were used to compare these values across two groups of cells. For comparisons of three or more groups of cells, these values were compared across drug conditions with analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests, using the Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) method to test the pairwise comparisons post hoc. Differences were considered significant when P ≤ 0.05. All data are means ± SE.

RESULTS

GABA release from ACs is prolonged after a brief stimulus.

Estimates of release underlying light-evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (L-IPSCs) from RBCs showed that GABA release was prolonged relative to a brief (30 ms) light stimulus (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b). However, the timing of L-IPSCs can be affected at many points in the retinal circuitry: the activation of photoreceptors, glutamate release from photoreceptors, BC activation, glutamate release from BCs, activation of ACs, and GABA release from ACs. To determine if GABA release from GABAergic ACs is inherently prolonged and asynchronous, we isolated the input from GABAergic ACs onto GABACRs on RBCs with a brief electrical stimulus in the IPL, where AC processes lie.

In response to a 1-ms electrical stimulus, the GABACR-mediated eIPSC onto RBCs was quite prolonged (Fig. 1A). The response to this stimulus for isolated GABACR eIPSCs was not significantly decreased by blocking glutamate receptors with CNQX (98.0 ± 7.7%, P = 0.8), showing that this stimulus isolated the AC input to RBCs. Although the kinetics of GABACRs are slow (Chang and Weiss 1999), the slow time course of the eIPSCs measured here is likely due to slow GABA release, since the eIPSC D37 is much longer than the decay of GABACR-mediated spontaneous currents (34.1 ± 2.1 ms) that reflect receptor kinetics (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b; Palmer 2006).

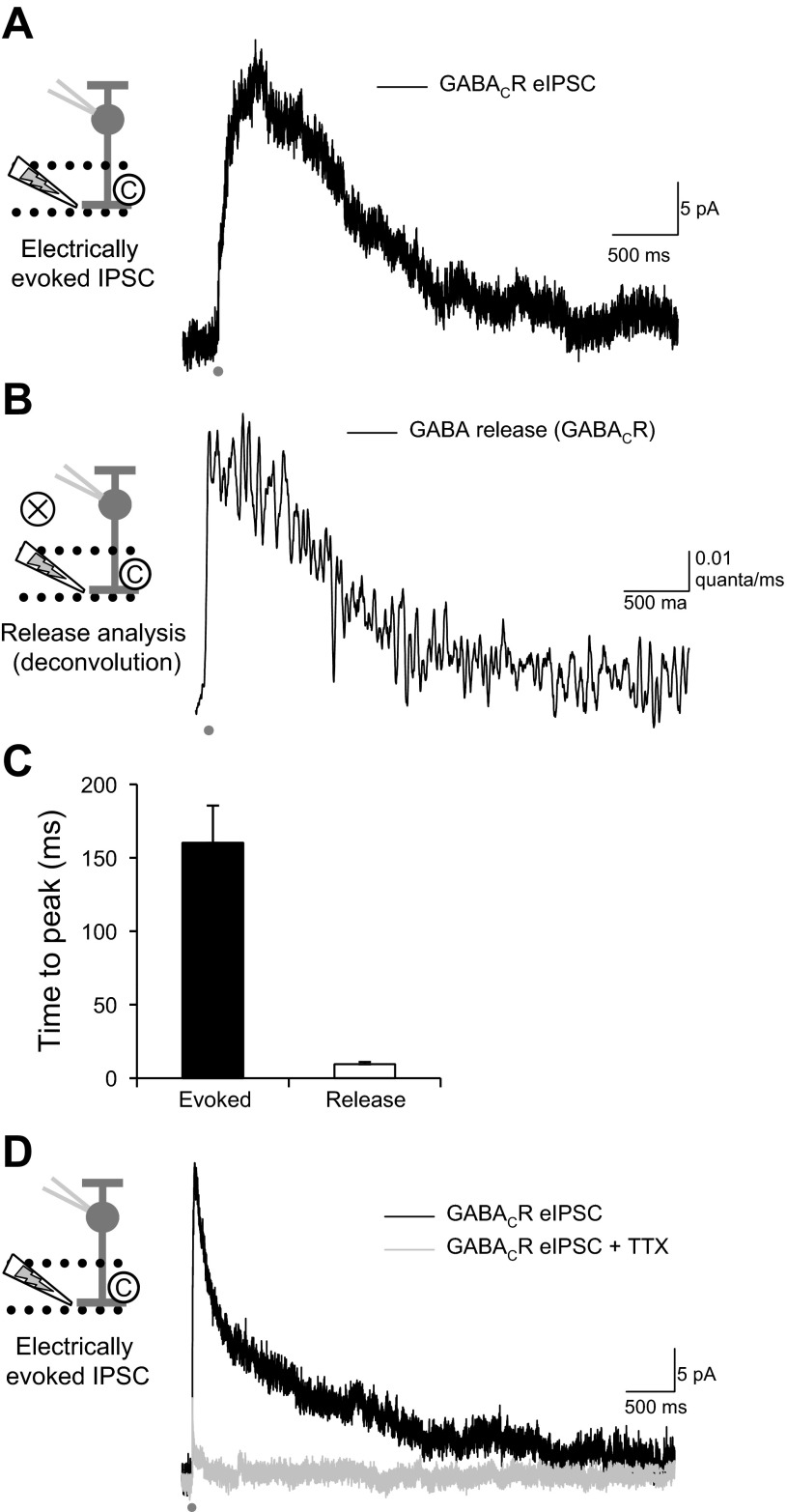

Fig. 1.

Electrically evoked GABAC receptor (GABACR) inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) resulting from amacrine cell (AC) action potentials are prolonged by slow GABA release. A: evoked IPSC (eIPSCs) were recorded from rod bipolar cells (RBCs) with an electrical stimulating pipette in the inner plexiform layer (stimulus artifact has been removed). The eIPSC was significantly prolonged past the initial stimulus (1 ms, dark gray bar). B: the release underlying the eIPSC was estimated with the deconvolution of an average GABACR spontaneous IPSC (sIPSC) from RBCs. The release was significantly prolonged past the initial stimulus (decay to 37% of peak, D37 = 877 ± 111 ms). The average charge transfer (Q) of the GABACR eIPSCs was 75,873 ± 11,247 pA·ms, which evoked an average of 146.9 ± 20.0 vesicles of neurotransmitter. C: the release waveform had a significantly shorter time to peak than the eIPSC. The release began very soon after the initial stimulus, suggesting some coordinated release from the AC. D: eIPSCs depend on action potential generation in presynaptic ACs, since they are significantly blocked by tetrodotoxin (TTX; 500 nM), with only 12.5 ± 5.4% (n = 5) of the eIPSC Q remaining.

To estimate the time course of GABA release onto GABACRs that underlies the eIPSC, we used deconvolution analysis (Diamond and Jahr 1995; Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b) of eIPSCs from individual RBCs combined with the average spontaneous GABACR-mediated current from mouse RBCs (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b). The deconvolution of eIPSCs with the sIPSC showed that GABA release onto RBC GABACRs is prolonged (Fig. 1B). We found that an average of 146.9 ± 20.0 vesicles of neurotransmitter were released by our electrical stimulus, and the release decreased with a D37 of 877 ± 111 ms, significantly prolonged past the initial stimulus. From anatomic studies, RBCs have an average of 48–60 GABACR containing synapses on their axon terminals (Chun et al. 1993; Fletcher et al. 1998). Our stimulus pipette likely did not activate all synapses onto RBCs because of its small size (∼2 μm) and might have activated release onto only one lobule of the RBC axon terminal (∼16–20 synapses per lobule) (Chun et al. 1993; Fletcher et al. 1998). Our estimate is that our stimulus evoked three to nine vesicles per release site. GABA release had a much faster time to peak than the GABACR-mediated eIPSC (Fig. 1C), which was expected since the release must come before the evoked current and GABACRs show significant cooperativity (Chang and Weiss 1999). Of the average 146.9 ± 20.1 vesicles released during a stimulus, an average of 1.8 ± 0.2 vesicles were released during the first 10 ms after the stimulus (3.3 ± 0.8%, n = 39). This suggests that the remaining 96.7% of the vesicles are released asynchronously from the neurotransmitter release site. This is also suggested by our estimate of multiple vesicles released per release site onto the RBCs.

RBCs receive feedback inhibitory input from the GABAergic A17 AC, which is exclusively activated by RBCs (Hartveit 1999; Nelson and Kolb 1985), as well as other GABAergic and glycinergic ACs (Kim et al. 1998; Strettoi et al. 1990) that are activated by cone BCs. A unique aspect in the activation of these ACs is that A17 ACs depend primarily on Ca2+ entry through Ca2+-permeable AMPARs instead of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Chavez et al. 2006; Grimes et al. 2009) to release GABA back onto RBCs and do not generate action potentials (Grimes et al. 2010; Hartveit 1999; Menger and Wässle 2000; Nelson and Kolb 1985). In contrast, the majority of the non-A17 AC-mediated inhibition to RBCs, in response to a glutamate puff, is mediated by action potential-generating ACs (Chavez et al. 2010).

A previous study suggested that inhibition to salamander BCs in response to electrical stimulation in the OPL (outer plexiform layer between photoreceptors and bipolar cells) depends primarily on the generation of action potentials in ACs and so may exclude the activation of ACs that do not have spikes (Shields and Lukasiewicz 2003). To determine if this was the case with our IPL stimulation in mammalian retinas, we recorded GABACR eIPSCs and applied TTX (500 nM) to block action potentials (Fig. 1D). When action potentials were blocked, very little of the GABACR eIPSC remained (12.5 ± 5.4%, n = 5, P < 0.001), suggesting that our electrical stimuli are primarily activating AC inputs that depend on action potential generation. This enables us to use electrical stimulation to investigate likely non-A17 AC input to RBCs (Chavez et al. 2010), which cannot easily be targeted through paired recordings, since the presynaptic AC identities are unknown. This electrical stimulation enables us to isolate action potential-dependent GABAergic AC inputs to RBCs. This is a situation where mechanisms of prolonged release may be especially important, since action potential-dependent release is generally very transient.

A prolonged Ca2+ signal causes prolonged GABA release.

This slow GABA release suggests that ACs are releasing GABA-containing vesicles primarily asynchronously. In studies in other brain systems (Cummings et al. 1996; Lu and Trussell 2000; Otsu et al. 2004), asynchronous release results from a prolonged Ca2+ signal in the presynaptic terminal that may originate at a distance from release sites. Because of this, asynchronous release is reduced by increasing slow Ca2+ buffering with EGTA, which reduces a prolonged Ca2+ signal, whereas synchronous release is only decreased by increasing fast Ca2+ buffering with BAPTA, which can reduce very fast, local Ca2+ signals (Cummings et al. 1996; Hefft and Jonas 2005; Lu and Trussell 2000; Otsu et al. 2004). To test if RBC GABA responses exhibited these characteristics of asynchronous release, we tested the effects of increasing slow Ca2+ buffering with EGTA-AM, a membrane-permeable analog of EGTA. Since EGTA is a slow buffer of Ca2+, EGTA-AM should not affect synchronous release where the Ca2+ channels are close to the release sites of neurotransmitter, but it will decrease a global Ca2+ buildup that is responsible for slow asynchronous release. We used a relatively low concentration of EGTA-AM (50 μM) and had 10 mM EGTA in the intracellular recording solution, so EGTA-AM should only have affected the presynaptic terminals. We found that EGTA-AM significantly decreased the charge transfer Q (Fig. 2, A and C; Table 1), D37 (Fig. 2D; Table 1), and peak of eIPSCs (Table 1). There was no change in the time to peak (P = 0.8), suggesting that increasing slow Ca2+ buffering does not speed the time course of release from ACs. This implies that global Ca2+ buildup is responsible for the slow release from ACs.

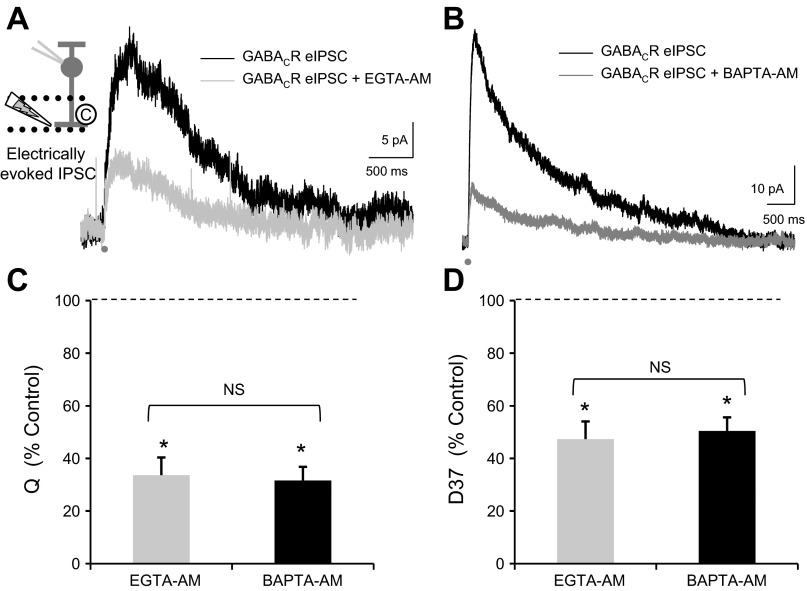

Fig. 2.

Increased Ca2+ buffering decreases RBC GABACR eIPSCs and shortens the decay. A and B: slow (EGTA-AM, 50 μM; A) and fast Ca2+ buffers (BAPTA-AM, 50 μM; B) were added to the extracellular solution while GABACR eIPSCs were recorded. C: both EGTA-AM and BAPTA-AM significantly decreased Q (EGTA-AM, n = 7, P < 0.001; BAPTA-AM, n = 11, P < 0.001) by similar amounts [EGTA-AM vs. BAPTA-AM: not significant (NS), t-test, P = 0.8]. D: both EGTA-AM and BAPTA-AM also significantly decreased D37 (EGTA-AM, P < 0.001; BAPTA-AM, P < 0.001) by similar amounts (EGTA-AM vs. BAPTA-AM: NS, t-test, P = 0.3). Values in C and D are normalized to the control GABACR current for each cell. *P < 0.001.

Table 1.

Average values for GABACR-mediated eIPSCs (normalized to GABACR eIPSC control)

| Q, %control | D37, %control | Peak, %control | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGTA-AM | 33.6 ± 6.7‡ | 57.3 ± 5.8‡ | 58.2 ± 8.1† | 7 |

| BAPTA-AM | 31.6 ± 5.2‡ | 50.5 ± 4.0‡ | 53.5 ± 8.3‡ | 11 |

| Nifedipine | 42.0 ± 7.3‡ | 74.3 ± 8.6* | 47.8 ± 6.9‡ | 10 |

| Cd2+ | 4.4 ± 3.2‡ | 6 | ||

| ω-Conotoxin | 71.7 ± 7.8* | 101.5 ± 6.7 | 62.6 ± 5.2† | 5 |

| ω-Conotoxin + nifedipine | 14.7 ± 1.9‡ | 51.5 ± 3.2† | 34.2 ± 9.3* | 4 |

| Ryanodine | 36.8 ± 8.6‡ | 38.8 ± 6.8‡ | 54.0 ± 8.9† | 6 |

| Nifedipine + ryanodine | 12.5 ± 5.1† | 14.0 ± 6.7† | 53.7 ± 12.2 | 3 |

Data are average values of charge transfer (Q), decay to 37% of peak (D37), and peak amplitude for GABAC receptor (GABACR)-mediated evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (eIPSCs), normalized to GABACR eIPSC control.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001 compared with control.

We also tested the effects of BAPTA-AM, which causes the faster Ca2+ buffer BAPTA to go into the presynaptic AC terminals. BAPTA-AM decreases synchronous and asynchronous types of release (Cummings et al. 1996; Lu and Trussell 2000; Otsu et al. 2004) because it can act quickly and thus prevent Ca2+ channels local to release sites from triggering release. BAPTA-AM also caused a significant decrease in Q (Fig. 2, B and C; Table 1), D37 (Fig. 2D; Table 1), and peak (Table 1). However, the decreases in Q (Fig. 2C, EGTA vs. BAPTA; t-test, P = 0.8), D37 (Fig. 2D; P = 0.3), and peak (P = 0.7) between EGTA-AM and BAPTA-AM are very similar. This suggests that ACs are primarily releasing GABA due to a large global increase in Ca2+ concentration. In agreement with this, BAPTA-AM caused no significant change in time to peak (P = 0.6), suggesting that there is not a large component of synchronous release that can be removed by increased Ca2+ buffering. This agrees with previous studies recording from cultured chick ACs that found prolonging the presynaptic Ca2+ signal could induce prolonged GABA release (Gleason et al. 1994).

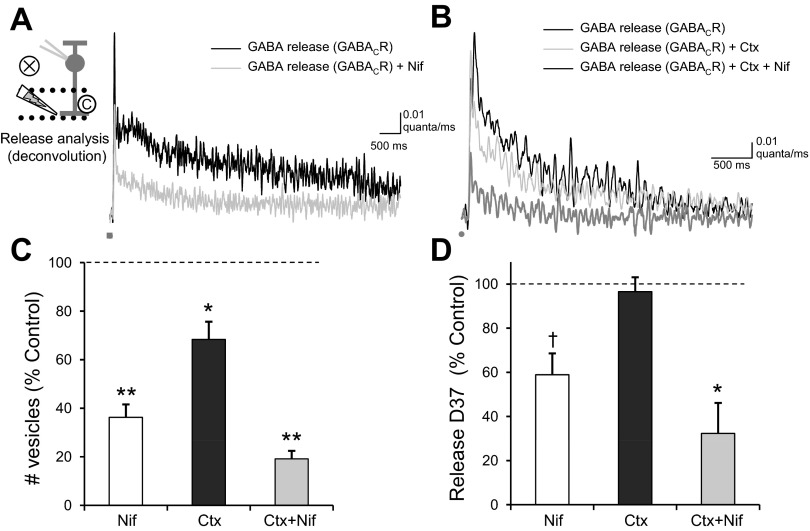

To investigate this further, we used deconvolution analysis to estimate the GABA release underlying the response to EGTA-AM and BAPTA-AM. Both EGTA-AM (Fig. 3A) and BAPTA-AM (Fig. 3B) significantly decreased the total number of vesicles released, measured as the area under the curve (Fig. 3C; Table 2). EGTA-AM and BAPTA-AM also decreased D37 (Fig. 3D; Table 2), which represents how long GABA is present through vesicle release and diffusion, and the peak of vesicle release (Table 2), which is the maximum number of vesicles released. There was no significant difference in the decrease in either Q, D37, or peak between EGTA-AM and BAPTA-AM (Q, P = 0.3; D37, P = 0.3; peak, P = 0.7). Neither EGTA-AM nor BAPTA-AM caused a significant change in the time to peak of release (EGTA-AM, P = 0.9; BAPTA-AM, P = 0.3). Slow buffering of Ca2+ causes a significant decrease in GABA eIPSCs and GABA release onto RBCs. This suggests that a prolonged Ca2+ signal in the presynaptic ACs is necessary to create this prolonged release.

Fig. 3.

Increased Ca2+ buffering decreases prolonged GABA release. A and B: the GABA release time course analyzed from the traces in Fig. 2, A and B, respectively. C: both EGTA-AM and BAPTA-AM significantly decreased the total number of vesicles released (EGTA-AM, n = 7, P < 0.05; BAPTA-AM, n = 11, P < 0.001) by similar amounts (EGTA-AM vs. BAPTA-AM: NS, t-test, P = 0.3). D: both EGTA-AM and BAPTA-AM also significantly decreased D37 (EGTA-AM, P < 0.05; BAPTA-AM, P < 0.05) by similar amounts (EGTA-AM vs. BAPTA-AM: NS, t-test, P = 0.3). Values in C and D are normalized to the release onto GABACRs for each cell. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001.

Table 2.

Average values for release from deconvolution of GABACR-mediated eIPSCs (normalized to release from GABACR eIPSC control)

| Q, %control | D37, %control | Peak, %control | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGTA-AM | 56.6 ± 14.7* | 77.2 ± 8.7† | 65.4 ± 15.0 | 7 |

| BAPTA-AM | 37.0 ± 5.0‡ | 54.6 ± 16.2‡ | 62.1 ± 12.5* | 11 |

| Nifedipine | 36.3 ± 5.3‡ | 65.1 ± 12.4† | 45.1 ± 8.1‡ | 10 |

| ω-Conotoxin | 68.4 ± 7.3* | 86.1 ± 10.5 | 70.8 ± 7.0* | 5 |

| ω-Conotoxin + nifedipine | 19.1 ± 3.3‡ | 66.5 ± 4.5* | 32.0 ± 10.2† | 4 |

| Ryanodine | 32.1 ± 8.3‡ | 45.9 ± 12.1‡ | 45.6 ± 12.2† | 6 |

| Nifedipine + ryanodine | 15.9 ± 1.9‡ | 9.63 ± 4.4† | 41.44 ± 12.11* | 3 |

Data are average values for Q, D37, and peak amplitude for release from deconvolution of GABACR-mediated eIPSCs, normalized to release from GABACR eIPSC control.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001 compared with control.

Slow Ca2+ channels mediate part of the slow Ca2+ signal.

To determine the origin of the Ca2+ signals in the presynaptic ACs, we first blocked all voltage-gated Ca2+ channels with Cd2+. This eliminated the GABACR-mediated eIPSC (Fig. 4A; Table 1). Since the response was eliminated, no peak or D37 could be measured after application of Cd2+. This suggests that all the GABA current we observe is due to the activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. A previous report (Chavez et al. 2006) showed that the majority of GABA release from A17 ACs, a major GABAergic input to RBCs, was triggered by Ca2+ movement through Ca2+-permeable AMPARs, not voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Given that Cd2+ blocks our entire eIPSC, this is another piece of evidence that we are directly activating AC processes and not presynaptic BC terminals.

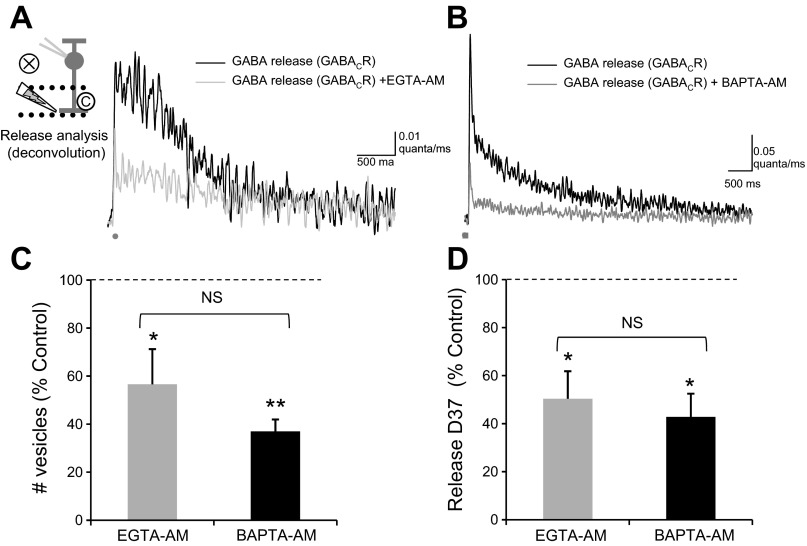

Fig. 4.

L-type and N-type Ca2+ channels contribute to RBC GABACR eIPSCs. A: blocking voltage-gated Ca2+ channels with Cd2+ (100 μM) eliminated the GABACR eIPSC (Q, n = 6, P < 0.001). B: blocking L-type Ca2+ channels with nifedipine (Nif; 10 μM) significantly reduced the Q of GABACR eIPSCs (n = 10, P < 0.001) and moderately decreased the D37 (P < 0.05). C: blocking N-type Ca2+ channels with ω-conotoxin (Ctx; 20 nM) caused a small decrease in Q (n = 5, P < 0.05) but no change in D37 (NS, P = 0.8). The addition of nifedipine to the ω-conotoxin (Nif+Ctx) caused an additional significant decrease in both Q (n = 4, P < 0.001) and D37 (P < 0.01). D: although all drug conditions significantly decreased Q (P < 0.05), there were significant differences between the drug conditions [ANOVA, P < 0.001, Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) post hoc]. Blocking all Ca2+ channels with Cd2+ caused a larger decrease in Q than either Nif (P < 0.005) or Ctx (P < 0.001), but there was no difference between Cd2+ and Ctx+Nif (NS, P = 0.37), suggesting that the eIPSCs were primarily mediated by L-type and N-type Ca2+ channels. The combination of Ctx+Nif caused a larger decrease in Q then either Nif (P < 0.05) or Ctx (P < 0.001) alone. E: there were also significant differences between the drug conditions in effects on D37 (ANOVA, P < 0.05, SNK post hoc). Nif (P < 0.05) and Ctx+Nif (P < 0.05) caused a significantly larger D37 decrease than Ctx alone, but there was no difference between the 2 nifedipine conditions (NS, P = 0.1). *P < 0.05; †P < 0.01; **P < 0.001.

We then wanted to test specific types of Ca2+ channels to determine if this global Ca2+ buildup is due to prolonged Ca2+ channel activation. We first tested L-type Ca2+ channels, because they have prolonged open times with little desensitization that could lead to a prolonged Ca2+ signal, as was seen previously in pairs of cultured chick ACs (Gleason et al. 1994). We recorded GABACR-mediated eIPSCs from RBCs and blocked L-type Ca2+ channels with nifedipine (Fig. 4B). Nifedipine significantly reduced Q, D37, and peak of GABACR-mediated eIPSCs (Fig. 4, D and E; Table 1) with no change in time to peak (P = 0.7). This suggests that L-type Ca2+ channels are mediating at least part of the prolonged Ca2+ signal.

In contrast, blocking fast N-type Ca2+ channels with ω-conotoxin (Fig. 4C) caused a small decrease in Q and peak (Fig. 4D; Table 1) but no change in D37 (Fig. 4E; P = 0.8) or time to peak (P = 0.7). The addition of nifedipine to the ω-conotoxin caused an additional significant decrease in Q, peak, and D37 (Fig. 4, D and E; Table 1) but not in time to peak (P = 0.12), leaving a Q that was not significantly different from that with Cd2+ [ANOVA Q, P < 0.001; SNK post hoc: Cd2+ vs. ω-conotoxin + nifedipine, not significant (NS), P = 0.37]. The decrease in D37 due to nifedipine (alone or applied after ω-conotoxin) was significantly different from the effect on D37 due to ω-conotoxin alone (ANOVA, P < 0.05; SNK post hoc: nifedipine vs. ω-conotoxin, P < 0.05; nifedipine + ω-conotoxin vs. ω-conotoxin, P < 0.05). This suggests that although the fast N-type Ca2+ channels mediate a portion of the Ca2+ signal in ACs, they do not contribute to the prolonged Ca2+ signal, as expected from their kinetics. A previous study analyzing the role of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in glutamate-evoked GABA release also showed that L-type and N-type Ca2+ channels played the largest roles in GABA release (Chavez et al. 2006), although they did not test the relative roles of the channels on the kinetics of the GABA response.

L-type and N-type Ca2+ channels also had significantly different effects on GABA release, as analyzed by deconvolution. Nifedipine, ω-conotoxin, and the combination of the two significantly decreased the total number of vesicles released (Fig. 5; Table 2) and the peak number of vesicles released (Table 2). However, nifedipine and ω-conotoxin + nifedipine caused a significant decrease in D37 (Table 2; Fig. 5D), whereas ω-conotoxin alone did not (P = 0.6), and the D37 decrease due to nifedipine was significantly different from that due to ω-conotoxin (ANOVA, P < 0.008; SNK post hoc: nifedipine vs. ω-conotoxin, P < 0.05; ω-conotoxin + nifedipine vs. ω-conotoxin, P < 0.05). None of the treatments caused a significant change in time to peak (nifedipine, P = 0.3; ω-conotoxin, P = 0.5; ω-conotoxin + nifedipine, P = 0.13) These results suggest that GABA release is triggered by both L-type and N-type Ca2+ channels but that L-type Ca2+ channels cause a prolonged Ca2+ signal that prolongs GABA release.

Fig. 5.

Blocking N-type and L-type Ca2+ channels decreases GABA release. A and B: the GABA release time course analyzed from the traces in Fig. 4, A and B, respectively. Nif (n = 10, P < 0.001), Ctx (n = 5, P < 0.05, and Ctx+Nif (n = 4, P < 0.001) significantly decreased the total number of vesicles released. C: there were significant differences between the drug conditions (ANOVA, P < 0.001, SNK post hoc), since both Nif (P < 0.01) and Ctx (P < 0.001) caused a significantly greater decrease in the number of vesicles released than Ctx alone. D: Nif (P < 0.01) and Ctx+Nif (P < 0.05) caused significant decreases in D37, whereas Ctx did not (P = 0.6). There were significant differences between the drug conditions (ANOVA, P < 0.008, SNK post hoc), since both Nif (P < 0.05) and Ctx+Nif (P < 0.05) caused a significantly greater decrease in D37 than Ctx alone. *P < 0.05; †P < 0.01; **P < 0.001.

Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release prolongs the Ca2+ signal.

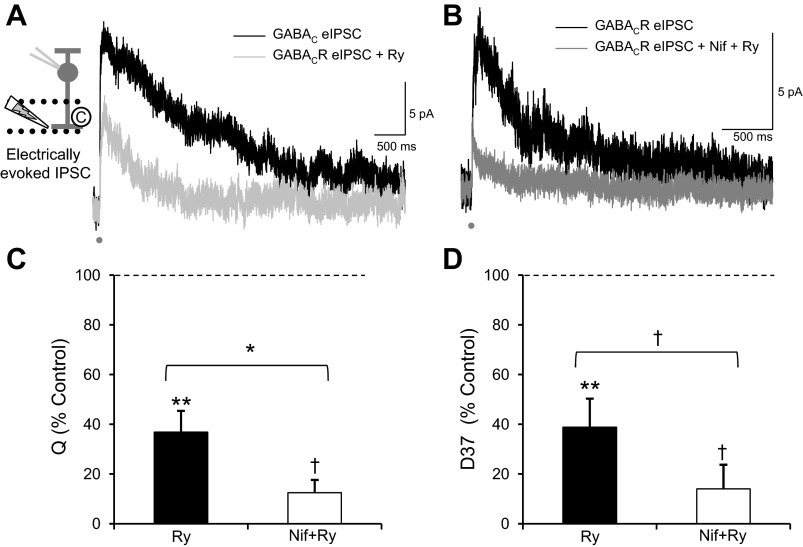

Although L-type Ca2+ channels are responsible for at least part of the prolonged Ca2+ signal, GABA release after L-type Ca2+ channels are blocked is still prolonged relative to the initial stimulus (Fig. 5A; D37 = 565.5 ± 203.5 ms). To determine what else could be mediating this slow Ca2+ signal, we tested the role of CICR by blocking ryanodine receptors with a high concentration of ryanodine (Fig. 6A). This caused a significant decrease in Q (Fig. 6C; Table 1), D37 (Fig. 6D; Table 1), and peak (Table 1). The change in Q differed among Ca2+ manipulations (ANOVA, P < 0.05; SNK post hoc). Ryanodine caused a similar amount of decrease in Q as increasing Ca2+ buffering with EGTA-AM (NS, P = 0.7) and blocking L-type Ca2+ channels with nifedipine (NS, P = 0.7) but a significantly greater decrease in Q than blocking N-type Ca2+ channels with ω-conotoxin (P < 0.05). The change in D37 also differed among Ca2+ manipulations (ANOVA, P < 0.001; SNK post hoc). Ryanodine caused a significantly greater decrease in D37 than nifedipine (P < 0.01) or ω-conotoxin (P < 0.001) but a decrease similar to that caused by EGTA-AM (NS, P = 0.1). Nifedipine and ryanodine applied together (Fig. 6B), to block both slow Ca2+ influx and CICR, caused an even greater decrease in Q (Fig. 6C) and D37 (Fig. 6D). This suggests that the Ca2+ signal that causes slow GABACR-mediated eIPSCs is prolonged by Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, in agreement with previous reports that tested the magnitude, but not the kinetics, of GABA release (Chavez et al. 2006, 2010; Medler and Gleason 2002; Sen et al. 2007).

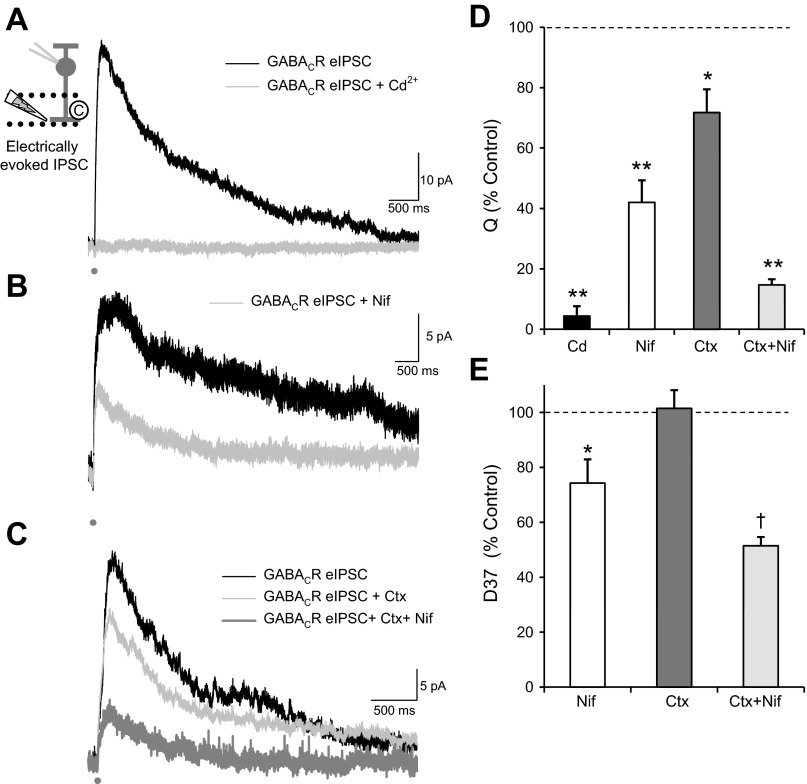

Fig. 6.

Ca2+ release from intracellular stores dominates the time course of RBC GABACR eIPSCs. A: blocking Ca2+ release from intracellular stores with ryanodine (Ry; 50 μM) to block Ry receptors significantly decreased Q (n = 6, P < 0.001) and D37 (P < 0.001) of GABACR eIPSCs. B: blocking both L-type Ca2+ channels with Nif and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores caused an even greater decrease in Q (n = 3, P < 0.01) and D37 (P < 0.01) of GABACR eIPSCs. C: adding both Nif and Ry caused a significantly greater decrease in Q than Ry alone (P < 0.05). D: the combination of Nif+Ry also caused a more significant decrease in D37 than Ry alone (P < 0.01). *P < 0.05; †P < 0.01; **P < 0.001.

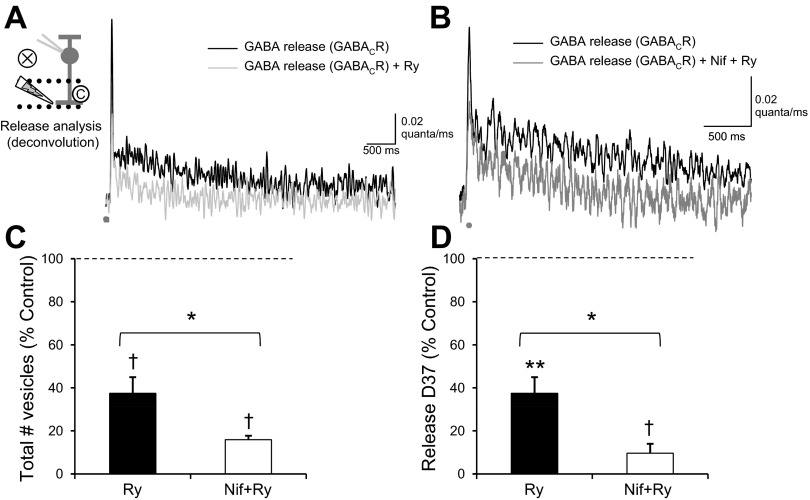

Blocking CICR also limited the release of GABA from ACs, as analyzed by deconvolution (Fig. 7A). Blocking ryanodine receptors decreased the amount of GABA release (Fig. 7C; Table 2), the peak of GABA release (Table 2), and the D37 of GABA release (Fig. 7D; Table 2) without a change in time to peak (P = 0.15). The change in the D37 of GABA release due to ω-conotoxin was significantly different (ANOVA P < 0.01, SNK) from that due to EGTA (P < 0.05), nifedipine (P < 0.05), and ryanodine (P < 0.01). Blocking both ryanodine receptors and L-type Ca2+ channels (Fig. 7B) caused a further decrease in the amount and decay of release. After both ryanodine receptors and L-type Ca2+ channels were blocked, the D37 of GABACR eIPSCs was only 110.0 ± 49.8 ms, a relatively synchronous time course of release. Together these results suggest that prolonged Ca2+ entry through L-type Ca2+ channels triggers CICR in GABAergic ACs. The combination of these two events produces the prolonged Ca2+ signal and prolonged GABA release onto RBCs.

Fig. 7.

Ca2+ release from intracellular stores prolongs GABA release onto GABACRs. A: the GABA release time course, analyzed from the traces in Fig. 6A, showed a decrease in the GABA release after application of Ry. B: GABA release was also decreased with the addition of Nif+Ry. C: blocking Ca2+ release from intracellular stores with ryanodine significantly decreased the number of vesicles released onto GABACRs (n = 6, P < 0.01). Nif+Ry significantly decreased the number of vesicles released onto GABACRs (n = 6, P < 0.01), more than Ry alone (P < 0.05). D: Ry also caused a significant decrease in the D37 of GABA release (P < 0.001), and Nif+Ry caused a larger decrease than Ry alone (P < 0.05). *P < 0.05; †P < 0.01; **P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that GABA release from ACs onto RBCs is inherently slow, due to a prolonged Ca2+ buildup in the presynaptic AC terminal. Slow L-type Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores contribute to this Ca2+ buildup and play a large role in creating the slow time course. ACs show prolonged, asynchronous release after an initial brief stimulus, which has not been previously seen in neurons. Retinal ACs may be unique interneurons that use the slow timing of neurotransmitter release as a way to match the timing of action potential-mediated neurotransmitter release from ACs to the slow potential synaptic ribbon release in BCs. Asynchronous release also presents a type of release that can be easily modulated by both the amplitude and the time course of Ca2+ signaling in the presynaptic terminal. This creates an additional potential avenue of differentiation of inhibition between signaling pathways in the retina.

Comparison with light stimuli.

Although we cannot record directly from the unidentified non-A17 presynaptic ACs that release GABA onto the RBCs, previous retina recordings suggest that our brief (1 ms) electrical stimulation does cause a brief depolarization in the retina. Brief electrical stimulation in the OPL (1 ms) produces brief BC depolarization (Higgs and Lukasiewicz 1999). Direct recordings from unidentified GABAergic ACs and starburst ACs have shown that a brief direct depolarization of ACs is likely to produce only one spike and a brief depolarization (Cohen 2001; Gleason et al. 1993). Also, a brief (10 ms) electrical stimulus in the ganglion cell (GC) layer evokes only one spike in recorded GCs (Margalit et al. 2011).

In a previous study L-IPSCs had an average D37 of 472.4 ± 82.7 ms, with average peak amplitude of 10.4 ± 1.4 pA (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b). However, it should be noted that the D37 of GABACR L-IPSCs increased with increasing light stimulus intensity, potentially due to spillover between GABAergic synapses, so this does not represent the maximum D37 for GABACR-mediated L-IPSCs. The eIPSCs we measured in the present study had larger response amplitudes (37.6 ± 5.2 pA) and a more prolonged D37 (1,349 ± 112 ms; Fig. 1B). This is likely due to the activation of more inputs with our focal stimulus than would normally be active during the light stimuli tested previously. Also, L-IPSCs are limited by network inhibition, but electrically evoked responses are not (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006a; 2010), since we are stimulating near the recorded RBC. These results show that prolonged GABACR-mediated IPSCs are present when the GABA input to RBCs is isolated. This suggests that upstream pathways influencing light-evoked GABAergic input to RBCs are not determining the time course of GABACR-mediated IPSCs.

Mechanisms of slow GABA release.

Our present results suggest that retinal ACs use primarily slow, asynchronous release, since EGTA-AM and BAPTA-AM have the same effects on GABACR-mediated eIPSCs. Synapses in other systems have shown varying proportions of asynchronous vs. synchronous release (Awatramani et al. 2005; Hefft and Jonas 2005; Lu and Trussell 2000), but a synapse that uses primarily asynchronous release after one stimulus has not been shown. However, a recent study showed neurons in the inferior olive that have primarily asynchronous release after multiple stimuli, but little synchronous release (Best and Regehr 2009). This synapse could have similar mechanisms to the GABAergic ACs, but potentially with less Ca2+ influx from a single stimulus or greater Ca2+ buffering capacity so that the synapse requires multiple stimuli to trigger prolonged release. Our results suggest that this slow GABA release is due to a prolonged Ca2+ signal in the GABAergic AC, triggered by the opening of L-type Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. However, other mechanisms have also been suggested to control the time course of Ca2+ signaling and neurotransmitter release from neurons.

A recent study, modeling Ca2+ signals in neurons, showed that differing amounts of parvalbumin, a natural Ca2+ buffer in neurons, can change the proportion of asynchronous release (Volman et al. 2011). The authors suggested that this change could underlie changes in GABA activity that happen in disease states such as schizophrenia. In other neurons, altered levels of survival motor neuron protein increased the bulk Ca2+ in the nerve terminals and significantly increased asynchronous release (Ruiz et al. 2010). Other studies have suggested that asynchronous release uses a distinct Ca2+ sensor for release, which has a higher affinity for Ca2+ and slower kinetics (Geppert et al. 1994; Sudhof 2002) than the synchronous Ca2+ sensor. Instead of synaptotagmin 1 or 2, which are the Ca2+ sensors for synchronous neurotransmitter release (Geppert et al. 1994; Kochubey and Schneggenburger 2011; Nishiki and Augustine 2004), asynchronous release has been suggested to use synaptotagmin 7 (Schonn et al. 2008; Wen et al. 2010) or Doc2 (Pang et al. 2011; Yao et al. 2011) as Ca2+ sensors. Synaptotagmin 1 and 2 have been shown to be expressed in BCs in the retina (Berntson and Morgans 2003; Fox and Sanes 2007), but it is not known what Ca2+ sensors GABAergic ACs express.

Functional role of slow GABA release in the retina.

We have previously shown that the time course of GABA and glycine release underlying light-evoked inhibition varies between inputs mediated by GABAC, GABAA, and glycine receptors (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b; Eggers et al. 2007). The proportion of these inputs shapes the time course of inhibition (Eggers et al. 2007; Sagdullaev et al. 2006), with slow GABACR-mediated inputs shaping the decay time of inhibition and faster GABAAR- and glycine receptor-mediated inputs shaping the peak of inhibition. The retina is organized to transmit multiple parallel pathways of information to the rest of the visual system, an organization that starts at the BC level. The most basic level of retinal organization is the separation between the pathways responding to dim light sensed by rod photoreceptors (RBCs) and the offset (OFF cone BC) and onset (ON cone BC) of brighter light sensed by cone photoreceptors. These three pathways have distinct excitatory inputs from rods vs. cones (RBCs vs. cone BCs) and metabotropic glutamate receptor 6 (mGluR6) vs. AMPA/kainate receptors (ON cone BCs vs. OFF cone BCs) that affect the timing of the inputs (Ashmore and Copenhagen 1980; Copenhagen et al. 1983; Li and DeVries 2006; Schnapf and Copenhagen 1982).

Several previous studies have shown that the proportions of the three inhibitory inputs vary between these pathways (Eggers et al. 2007; Sagdullaev et al. 2006), with inputs onto GABACRs comprising the largest inhibitory inputs in RBCs, moderate in ON cone BCs, and least in OFF cone BCs. The proportion of GABACR-mediated inhibition determines the timing of inhibition, potentially to match the timing of excitation to these pathways (Ashmore and Copenhagen 1980; Copenhagen et al. 1983; Eggers et al. 2007; Li and DeVries 2006; Schnapf and Copenhagen 1982). Tuning the time course of neurotransmitter release is an adaptable way for the retina to tune the time course of inhibition. If other AC inhibition is similar to GABA release onto RBC GABACRs, then changing the time course of the Ca2+ signal in the presynaptic AC would change the time course of GABA release. This could be done quickly by phosphorylating Ca2+ channels (Peterson et al. 1999; Yue et al. 1990) or on a longer time course by changing the expression levels of Ca2+ buffers or receptors for CICR. Additionally, several studies have shown that the short-term plasticity of GABA release onto BCs and glutamate release from BCs operate on distinct time scales that affect the signaling onto downstream GCs (Li et al. 2007; Sagdullaev et al. 2011). Distinct mechanisms of release could function in this process, as well.

AC inhibitory inputs tune BC outputs, either directly on the BC axon terminal or on the dendrites of retinal GCs that receive BC output. BCs are nonspiking neurons that have a unique mechanism of neurotransmitter release, the ribbon synapse. The ribbon synapse is specialized for allowing the graded release of neurotransmitter over longer periods of time (Innocenti and Heidelberger 2008; von Gersdorff and Matthews 1997), although it is also capable of very quick release (Singer and Diamond 2003). Thus the slow release from retinal ACs may also be a mechanism to match the slow release from BCs.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY018131 (to E. D. Eggers) and T32 HL007249 (to J. M. Moore-Dotson).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.D.E. conception and design of research; E.D.E., J.S.K., and J.M.M.-D. analyzed data; E.D.E. interpreted results of experiments; E.D.E. prepared figures; E.D.E. drafted manuscript; E.D.E., J.S.K., and J.M.M.-D. edited and revised manuscript; E.D.E., J.S.K., and J.M.M.-D. approved final version of manuscript; J.S.K. and J.M.M.-D. performed experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Eggers laboratory and Dr. Peter Lukasiewicz for helpful discussion and comments on this manuscript and Adam Bernstein for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- Ashmore JF, Copenhagen DR. Different postsynaptic events in two types of retinal bipolar cell. Nature 288: 84–86, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awatramani GB, Turecek R, Trussell LO. Staggered development of GABAergic and glycinergic transmission in the MNTB. J Neurophysiol 93: 819–828, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson AK, Morgans CW. Distribution of the presynaptic calcium sensors, synaptotagmin I/II and synaptotagmin III, in the goldfish and rodent retinas. J Vis 3: 274–280, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best AR, Regehr WG. Inhibitory regulation of electrically coupled neurons in the inferior olive is mediated by asynchronous release of GABA. Neuron 62: 555–565, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield SA. Relationship between receptive and dendritic field size of amacrine cells in the rabbit retina. J Neurophysiol 68: 711–725, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges S, Gleason E, Turelli M, Wilson M. The kinetics of quantal transmitter release from retinal amacrine cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 6896–6900, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Weiss DS. Channel opening locks agonist onto the GABAC receptor. Nat Neurosci 2: 219–225, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez AE, Grimes WN, Diamond JS. Mechanisms underlying lateral GABAergic feedback onto rod bipolar cells in rat retina. J Neurosci 30: 2330–2339, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez AE, Singer JH, Diamond JS. Fast neurotransmitter release triggered by Ca influx through AMPA-type glutamate receptors. Nature 443: 705–708, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun MH, Han SH, Chung JW, Wässle H. Electron microscopic analysis of the rod pathway of the rat retina. J Comp Neurol 332: 421–432, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen ED. Voltage-gated calcium and sodium currents of starburst amacrine cells in the rabbit retina. Vis Neurosci 18: 799–809, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhagen DR, Ashmore JF, Schnapf JK. Kinetics of synaptic transmission from photoreceptors to horizontal and bipolar cells in turtle retina. Vision Res 23: 363–369, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings DD, Wilcox KS, Dichter MA. Calcium-dependent paired-pulse facilitation of miniature EPSC frequency accompanies depression of EPSCs at hippocampal synapses in culture. J Neurosci 16: 5312–5323, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond JS, Jahr CE. Asynchronous release of synaptic vesicles determines the time course of the AMPA receptor-mediated EPSC. Neuron 15: 1097–1107, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong CJ, Werblin FS. Temporal contrast enhancement via GABAC feedback at bipolar terminals in the tiger salamander retina. J Neurophysiol 79: 2171–2180, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers ED, Lukasiewicz PD. GABAA, GABAC and glycine receptor-mediated inhibition differentially affects light-evoked signalling from mouse retinal rod bipolar cells. J Physiol 572: 215–225, 2006a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers ED, Lukasiewicz PD. Interneuron circuits tune inhibition in retinal bipolar cells. J Neurophysiol 103: 25–37, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers ED, Lukasiewicz PD. Receptor and transmitter release properties set the time course of retinal inhibition. J Neurosci 26: 9413–9425, 2006b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers ED, McCall MA, Lukasiewicz PD. Presynaptic inhibition differentially shapes transmission in distinct circuits in the mouse retina. J Physiol 582: 569–582, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euler T, Wässle H. Different contributions of GABAA and GABAC receptors to rod and cone bipolar cells in a rat retinal slice preparation. J Neurophysiol 79: 1384–1395, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher EL, Koulen P, Wässle H. GABAA and GABAC receptors on mammalian rod bipolar cells. J Comp Neurol 396: 351–365, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MA, Sanes JR. Synaptotagmin I and II are present in distinct subsets of central synapses. J Comp Neurol 503: 280–296, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geppert M, Goda Y, Hammer RE, Li C, Rosahl TW, Stevens CF, Sudhof TC. Synaptotagmin I: a major Ca2+ sensor for transmitter release at a central synapse. Cell 79: 717–727, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh KK, Bujan S, Haverkamp S, Feigenspan A, Wässle H. Types of bipolar cells in the mouse retina. J Comp Neurol 469: 70–82, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason E, Borges S, Wilson M. Control of transmitter release from retinal amacrine cells by Ca2+ influx and efflux. Neuron 13: 1109–1117, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason E, Borges S, Wilson M. Synaptic transmission between pairs of retinal amacrine cells in culture. J Neurosci 13: 2359–2370, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes WN, Li W, Chavez AE, Diamond JS. BK channels modulate pre- and postsynaptic signaling at reciprocal synapses in retina. Nat Neurosci 12: 585–592, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes WN, Zhang J, Graydon CW, Kachar B, Diamond JS. Retinal parallel processors: more than 100 independent microcircuits operate within a single interneuron. Neuron 65: 873–885, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartveit E. Reciprocal synaptic interactions between rod bipolar cells and amacrine cells in the rat retina. J Neurophysiol 81: 2923–2936, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefft S, Jonas P. Asynchronous GABA release generates long-lasting inhibition at a hippocampal interneuron-principal neuron synapse. Nat Neurosci 8: 1319–1328, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs MH, Lukasiewicz PD. Glutamate uptake limits synaptic excitation of retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci 19: 3691–3700, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti B, Heidelberger R. Mechanisms contributing to tonic release at the cone photoreceptor ribbon synapse. J Neurophysiol 99: 25–36, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IB, Lee MY, Oh S, Kim KY, Chun M. Double-labeling techniques demonstrate that rod bipolar cells are under GABAergic control in the inner plexiform layer of the rat retina. Cell Tissue Res 292: 17–25, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirischuk S, Grantyn R. Intraterminal Ca2+ concentration and asynchronous transmitter release at single GABAergic boutons in rat collicular cultures. J Physiol 548: 753–764, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochubey O, Schneggenburger R. Synaptotagmin increases the dynamic range of synapses by driving Ca2+-evoked release and by clamping a near-linear remaining Ca2+ sensor. Neuron 69: 736–748, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GL, Vigh J, von Gersdorff H. Short-term depression at the reciprocal synapses between a retinal bipolar cell terminal and amacrine cells. J Neurosci 27: 7377–7385, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, DeVries SH. Bipolar cell pathways for color and luminance vision in a dichromatic mammalian retina. Nat Neurosci 9: 669–675, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Trussell LO. Inhibitory transmission mediated by asynchronous transmitter release. Neuron 26: 683–694, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald RL, Twyman RE. Kinetic properties and regulation of GABAA receptor channels. Ion Channels 3: 315–343, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margalit E, Babai N, Luo J, Thoreson WB. Inner and outer retinal mechanisms engaged by epiretinal stimulation in normal and rd mice. Vis Neurosci 28: 145–154, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medler K, Gleason EL. Mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering regulates synaptic transmission between retinal amacrine cells. J Neurophysiol 87: 1426–1439, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menger N, Wässle H. Morphological and physiological properties of the A17 amacrine cell of the rat retina. Vis Neurosci 17: 769–780, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R, Kolb H. A17: a broad-field amacrine cell in the rod system of the cat retina. J Neurophysiol 54: 592–614, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiki T, Augustine GJ. Synaptotagmin I synchronizes transmitter release in mouse hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 24: 6127–6132, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsu Y, Shahrezaei V, Li B, Raymond LA, Delaney KR, Murphy TH. Competition between phasic and asynchronous release for recovered synaptic vesicles at developing hippocampal autaptic synapses. J Neurosci 24: 420–433, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer MJ. Functional segregation of synaptic GABAA and GABAC receptors in goldfish bipolar cell terminals. J Physiol 577: 45–53, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang ZP, Bacaj T, Yang X, Zhou P, Xu W, Sudhof TC. Doc2 supports spontaneous synaptic transmission by a Ca2+-independent mechanism. Neuron 70: 244–251, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang ZP, Sudhof TC. Cell biology of Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol 22: 496–505, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BZ, DeMaria CD, Adelman JP, Yue DT. Calmodulin is the Ca2+ sensor for Ca2+-dependent inactivation of L-type calcium channels. Neuron 22: 549–558, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz R, Casanas JJ, Torres-Benito L, Cano R, Tabares L. Altered intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in nerve terminals of severe spinal muscular atrophy mice. J Neurosci 30: 849–857, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagdullaev BT, Eggers ED, Purgert R, Lukasiewicz PD. Nonlinear interactions between excitatory and inhibitory retinal synapses control visual output. J Neurosci 31: 15102–15112, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagdullaev BT, McCall MA, Lukasiewicz PD. Presynaptic inhibition modulates spillover, creating distinct dynamic response ranges of sensory output. Neuron 50: 923–935, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnapf JL, Copenhagen DR. Differences in the kinetics of rod and cone synaptic transmission. Nature 296: 862–864, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonn JS, Maximov A, Lao Y, Sudhof TC, Sorensen JB. Synaptotagmin-1 and -7 are functionally overlapping Ca2+ sensors for exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 3998–4003, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen M, McMains E, Gleason E. Local influence of mitochondrial calcium transport in retinal amacrine cells. Vis Neurosci 24: 663–678, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CR, Lukasiewicz PD. Spike-dependent GABA inputs to bipolar cell axon terminals contribute to lateral inhibition of retinal ganglion cells. J Neurophysiol 89: 2449–2458, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CR, Tran MN, Wong RO, Lukasiewicz PD. Distinct ionotropic GABA receptors mediate presynaptic and postsynaptic inhibition in retinal bipolar cells. J Neurosci 20: 2673–2682, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JH, Diamond JS. Sustained Ca2+ entry elicits transient postsynaptic currents at a retinal ribbon synapse. J Neurosci 23: 10923–10933, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strettoi E, Dacheux RF, Raviola E. Synaptic connections of rod bipolar cells in the inner plexiform layer of the rabbit retina. J Comp Neurol 295: 449–466, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhof TC. Synaptotagmins: why so many? J Biol Chem 277: 7629–7632, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WR. TTX attenuates surround inhibition in rabbit retinal ganglion cells. Vis Neurosci 16: 285–290, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volgyi B, Xin D, Bloomfield SA. Feedback inhibition in the inner plexiform layer underlies the surround-mediated responses of AII amacrine cells in the mammalian retina. J Physiol 539: 603–614, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volman V, Behrens MM, Sejnowski TJ. Downregulation of parvalbumin at cortical GABA synapses reduces network gamma oscillatory activity. J Neurosci 31: 18137–18148, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gersdorff H, Matthews G. Depletion and replenishment of vesicle pools at a ribbon-type synaptic terminal. J Neurosci 17: 1919–1927, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H, Linhoff MW, McGinley MJ, Li GL, Corson GM, Mandel G, Brehm P. Distinct roles for two synaptotagmin isoforms in synchronous and asynchronous transmitter release at zebrafish neuromuscular junction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 13906–13911, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Gaffaney JD, Kwon SE, Chapman ER. Doc2 is a Ca2+ sensor required for asynchronous neurotransmitter release. Cell 147: 666–677, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue DT, Backx PH, Imredy JP. Calcium-sensitive inactivation in the gating of single calcium channels. Science 250: 1735–1738, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng JJ, Lee S, Zhou ZJ. A developmental switch in the excitability and function of the starburst network in the mammalian retina. Neuron 44: 851–864, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]