Abstract

The airway mucosa and the alveolar surface form dynamic interfaces between the lung and the external environment. The epithelial cells lining these barriers elaborate a thin liquid layer containing secreted peptides and proteins that contribute to host defense and other functions. The goal of this study was to develop and apply methods to define the proteome of porcine lung lining liquid, in part, by leveraging the wealth of information in the Sus scrofa database of Ensembl gene, transcript, and protein model predictions. We developed an optimized workflow for detection of secreted proteins in porcine bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and in methacholine-induced tracheal secretions [airway surface liquid (ASL)]. We detected 674 and 3,858 unique porcine-specific proteins in BAL and ASL, respectively. This proteome was composed of proteins representing a diverse range of molecular classes and biological processes, including host defense, molecular transport, cell communication, cytoskeletal, and metabolic functions. Specifically, we detected a significant number of secreted proteins with known or predicted roles in innate and adaptive immunity, microbial killing, or other aspects of host defense. In greatly expanding the known proteome of the lung lining fluid in the pig, this study provides a valuable resource for future studies using this important animal model of pulmonary physiology and disease.

Keywords: proteomics, airway surface liquid, bronchoalveolar lavage, porcine lung

the passageways of the mammalian respiratory tract are bathed by secretions that play critically important roles in protecting the organism from microbial and environmental insults and promoting normal lung function. In the conducting airways, this fluid layer is known as airway surface liquid (ASL). ASL, a complex mixture of secreted proteins, peptides, and mucins as well as electrolytes and water, represents the combined contributions of the surface and submucosal gland epithelia of the conducting airways (5, 85). The varied roles of these gene products include modulating inflammation, promoting wound healing, maintaining ASL volume homeostasis, and transporting various nutrients and lipids in the extracellular milieu. In particular, ASL possesses a redundant and polyfunctional array of secreted peptides and proteins with host defense and immunomodulatory properties (reviewed in Ref. 7). In the gas-exchange regions of the lung, epithelia secrete a liquid known as the alveolar subphase, which contains pulmonary surfactant, a potent mixture of lipids and proteins necessary for proper mechanical functioning of the lung. In addition, like the ASL of the conducting airways, alveolar secretions include a number of innate immune factors involved in pulmonary host defenses. The coordinated functions of these secreted products help maintain lung health.

To better understand the functions of these compartments, proteomics approaches have been used to help identify the secreted proteins that comprise the ASL and alveolar subphase (collectively termed lung lining liquid). In past studies, researchers have used two-dimensional gel electrophoresis or other fractionation methods coupled with mass spectrometry (MS) to investigate lung lining liquid composition in a variety of fluids sampled from the human respiratory tract: nasal lavage fluid (49, 50), bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid (14, 28, 44, 47, 48, 50, 53, 58, 83, 84, 87), induced sputum (38, 60), and apical washings from cultured human bronchial epithelia (38). A serous cell model of airway submucosal glands using apical fluid from Calu-3 cells was used to investigate the regulation of antiprotease and antimicrobial secreted proteins (37). Notably, these proteomic tools provide a means to assess global changes in the composition of respiratory secretions in response to various inflammatory stimuli (12, 47–50) or in association with certain disease states (44, 53, 58, 83, 84, 87). Proteomic techniques have also been used to identify the BAL fluid proteins from wild-type mice (28, 31) and in murine models of lung injury and disease (13, 17, 28, 89). Here, we used a shotgun MS approach to define the repertoire of secreted peptide and protein components of the porcine lung.

The pig offers several advantages as an animal model for studies of lung biology and disease states. Porcine lungs share many similarities with human lungs in terms of size and structure (71). Also, unlike mice, the relatively long lifespan of pigs (10–20 years on average) makes them well suited for studies of progressive lung diseases (71). Porcine lungs have previously been used in many areas of lung research, including studies of surfactant composition and function (76), lung development (29), infectious diseases including influenza and porcine specific infections (27, 51, 61, 65), lung transplantation (46, 52, 59), responses to various types of lung injury (11, 32), and testing of gene therapy vectors (20, 57). Additionally, pigs have been used to model a number of lung diseases and conditions, including pulmonary hypertension (9), bronchiolitis obliterans (2), asthma (82), and cystic fibrosis (CF) (15, 43, 71, 77). Notably, the CF pig model has provided insights into the development of CF lung disease, an aspect that was previously difficult or impossible to study in murine CF models (15, 62, 66, 77).

In contrast to the human and the mouse, the lung lining liquid composition of pig airways is poorly characterized. The components of the ASL and BAL in the normal pig lung are largely unknown and it is likely that there are hundreds of proteins and peptides that have never been identified. Proteomic analysis of BAL and ASL has posed formidable challenges due to variable protein composition and small sample volumes, which make it difficult to identify relevant biomarkers against the background of intracellular proteins from cell shedding and other processes (28, 31). Additionally, the number of well-annotated porcine protein sequences lags far behind the available genomic information. In this study, a global proteomic analysis to identify the proteins in wild-type porcine ASL and BAL was performed to establish a foundation for future research. To create a useful pig-specific protein database for MS data analysis, we annotated Ensembl Sus scrofa FASTA protein entries with protein and gene names. These data provided a comprehensive profile of lining liquid components in healthy lung and new insights into the biology of this important animal model. This repository is an important resource for future comparative studies of the alterations in secreted factors that may occur in association with CF and other porcine models of pulmonary disease states.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Protocols and Collection of Bronchoalveolar Lavage and Airway Surface Liquid

Samples were collected from wild-type pigs as previously described (62, 71, 72, 77). All experimental techniques were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Iowa.

For BAL collection, six newborn pigs were euthanized within 12 h of birth by administering Euthasol (90 mg/kg iv) and lungs were excised by aseptic technique. To lavage, 1/16-in.-diameter sterile polyethylene tubing was inserted into the mainstem bronchi and lungs were washed with 5 ml of normal saline. This procedure was repeated three times for each excised lung and the collected washes from an individual animal were immediately pooled and placed on ice. Then each pooled BAL was centrifuged at a low speed (228 g) and the supernatant transferred to a fresh tube. Clarified BAL was buffer exchanged against 100 mM tetraethylammonium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) by using Amicon Ultra-15 3-kDa molecular weight cutoff filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Total protein concentrations were estimated by the Bradford assay. Samples were stored frozen at −80°C until use.

Porcine ASL was collected from five wild-type pigs within 12 h of birth. For this procedure, we used an established bronchoscopic microprobe method (23) to collect native secretions from the trachea and first generation bronchi. Methacholine was used to stimulate secretion after initial studies revealed that it was not possible to collect secretions from newborn animals without stimulation (66). We reasoned that this method would allow us to collect the net contributions of airway and submucosal gland cells in response to a strong neurochemical stimulus. Pigs were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (20 mg/kg im) and xylazine (2 mg/kg im), followed by propofol (2 mg/kg iv); saline was given intravenously to prevent dehydration. Once an animal had reached the proper plane of anesthesia, the neck was dissected to expose the trachea. Tracheal secretion was stimulated by administering methacholine (2.5 mg/kg iv). After ∼5 min, tracheal secretions were collected by making a small incision in the tracheal wall and inserting a sterile polyester-tipped applicator (Puritan Medical Products, Guilford, ME) to swab the lumen of the trachea. Then the probe was inserted into a microcentrifuge tube and secretions were recovered by centrifugation. This procedure generally resulted in recovery of ∼10–20 μl of ASL from each animal. Samples were immediately placed on ice and frozen at −80°C until use. Following ASL collection, pigs were euthanized with Euthasol.

Protein Preparation and Mass Spectrometry

Bronchoalveolar lavage.

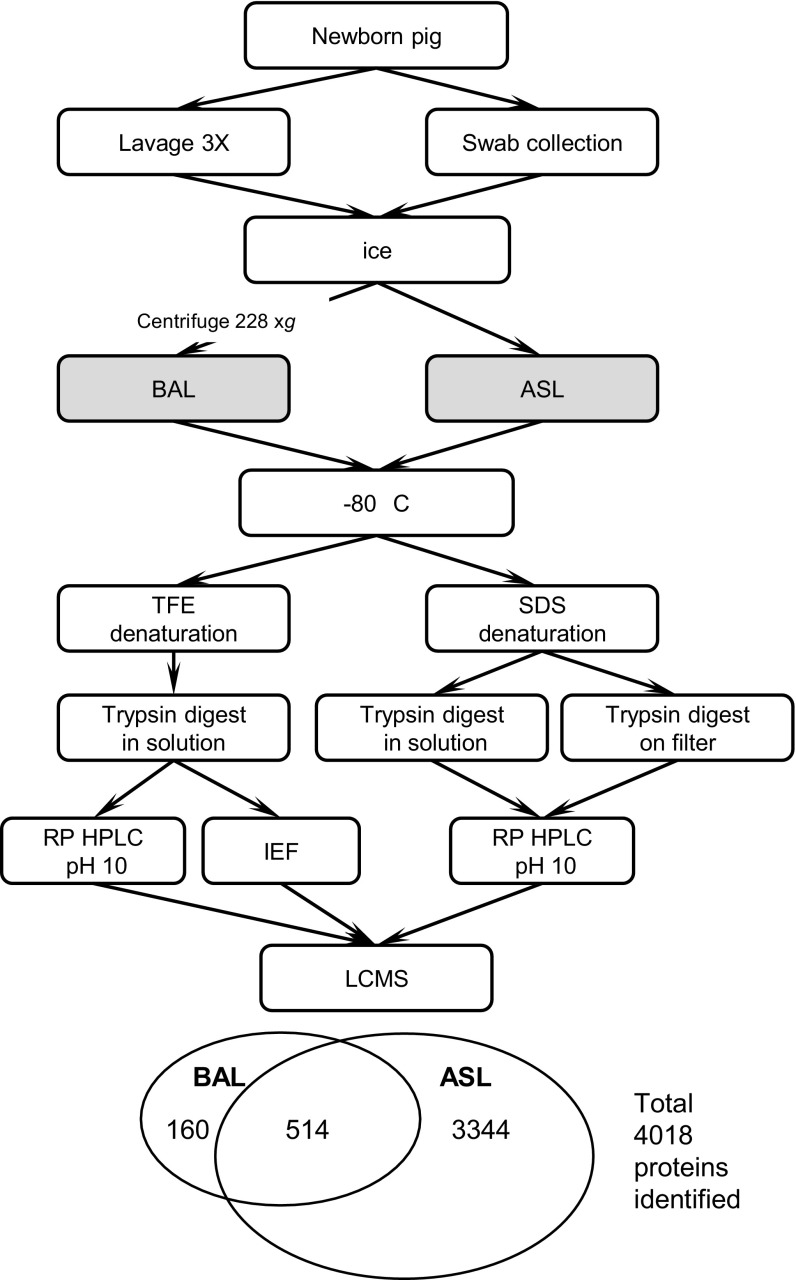

The workflow for BAL preparation and processing is shown in Fig. 1. Upon thawing, 100 μg of protein was denatured with trifluoroethanol (TFE), trypsin digested (81), divided into two aliquots, and fractionated by isoelectric focusing (16, 25, 34) and alkaline reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (reverse-phase HPLC) (21, 22, 24). For BAL1 and BAL2, eight HPLC fractions were collected and for BAL3–6 a total of 30 fractions were collected. Peptide fractions were analyzed by LCMS on a QSTAR Elite mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Foster City, CA).

Fig. 1.

Workflow for collection, processing, and mass spectrometric analyses of pig bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and airway surface liquid (ASL). TFE, trifluoroethanol; IEF, isoelectric focusing.

Airway surface liquid.

The workflow for ASL preparation and processing is shown in Fig. 1. ASL proteins were solubilized in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), reduced, alkylated, and trypsin digested either by a filter-assisted solubilization protocol or by in-solution digestion followed by SDS removal using strong cation exchange (68, 75). Peptides were fractionated offline (n = 20) by using alkaline reverse-phase HPLC followed by LCMS on an LTQ Velos Orbitrap (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA).

Pig Protein Sequence Database Development and Protein Identification

The Ensembl Sus scrofa 10.2.67.pep. all protein FASTA database, containing 23,118 entries, was annotated with protein and gene names as follows. First, a program was developed to query all Ensembl entries for each protein accession code. The gene name, description, database source (e.g., UniProt, NCBI, HGNC), and entry name, if present, were parsed out and assembled to replace the original Ensembl annotation. For those entries for which the description was “uncharacterized protein” or “novel transcript,” the gene name, if present, was used to search the human UniProt Knowledgebase v2012_07 and the human protein description used. The source for these entries is designated UniProtKB(Hu). The final database contained protein sequences and Ensembl accession codes for all of the original 23,118 entries with 18,664 entries fully annotated with descriptive protein names.

Protein identification was accomplished by using ProteinPilot 4.0 software (AB Sciex) and the integrated false discovery rate (FDR) analysis function (79) with a concatenated reversed database. Search parameters were trypsin enzyme specificity, carbamidomethyl cysteine, and thorough search effort. Proteins with ≤5% local FDR and peptides with ≤1% global FDR were reported. For pig Ensembl entries that did not contain a protein name, the gene name was mapped to the human protein name. For the novel transcripts and uncharacterized proteins lacking a gene name that were detected at an FDR threshold of ≤5%, a sequence similarity search was performed by using BLAST (4) and the protein with the highest score was reported. If equivalent top-scoring BLAST matches occurred, the human match was reported whenever present. A subset of the data was also searched by using mammalian sequences in the UniProt SwissProt database. For both BAL and ASL, proteins detected from each individual sample were aligned to a master search result comprised of all data by using the Protein Alignment Template V2.000p beta (78). The master search was a reference protein identification list produced by searching the MS data from all samples to produce a single result. To perform the analysis of the intersection of protein identifications, the threshold for the master search was set at 1% global FDR and the threshold for the individual samples set to 5% local FDR. These settings were chosen to ensure that high-quality identifications from each set were matched. The annotation of protein molecular function and biological processes was performed by using PANTHER Gene Ontology (GO) (80).

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

To visualize proteins in lung lining fluid, BAL and ASL samples (2 μg total protein per lane) were electrophoresed through 4–20% Tris·HCl gradient gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and silver stained by use of the Silver Stain Plus kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). To immunoblot for PLUNC and SP-D, total protein from pig BAL and ASL was separated on 4–20% Tris·HCl gels (20 μg/lane for BAL and 5 μg/lane for ASL) and transferred to PVDF membranes, followed by blocking overnight in TBS-Tween containing 2% BSA. To detect PLUNC protein, membranes were incubated with a monoclonal antibody recognizing human and porcine palate, lung, nasal epithelium clone (PLUNC; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) diluted 1:250 in TBS-Tween, for 1.5 h at room temperature. Membranes were washed four times with TBS-Tween, then incubated with secondary antibody (Immunopure goat anti-mouse conjugated to horseradish peroxidase; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a 1:20,000 dilution for 1 h. After five more washes in TBS-Tween, protein bands were detected with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For SP-D detection, membranes were incubated with anti-porcine SP-D diluted 1:500 in TBS-Tween for 1.5 h at room temperature, followed by four washes in TBS-Tween. Membranes were incubated with secondary antibody (Immunopure goat anti-rabbit conjugated to horseradish peroxidase; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 1:20,000 for 1 h, followed by five washes in TBS-Tween and chemiluminescent detection as described above. Immunoblotting for MUC5AC was carried out under nonreducing conditions as described by Lacunza and colleagues (45). Briefly, BAL and ASL samples were diluted in SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 25% SDS (125 mM Tris·HCl, pH 6.8; 25% SDS; 20% glycerol; 0.004% bromophenol blue) prior to boiling at 95°C. Samples were loaded onto 7.5% Tris·HCl gels (5 μg/lane) and electrophoresed for ∼2 h. Then proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes by electroblotting overnight at 4°C, by using methanol-free transfer buffer containing 0.1% SDS. To block nonspecific immunoreactivity, the membranes were incubated for 1–2 h at room temperature in TBS-Tween containing 2% BSA. Then they were incubated for 1.5 h with a monoclonal antibody recognizing MUC5AC (Clone 45M1; Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted 1:500 in TBS-Tween. Next they were washed four times in TBS-Tween and incubated for 1 h with secondary antibody (Immunopure goat anti-mouse conjugated to horseradish peroxidase; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a 1:20,000 dilution. After five washes in TBS-Tween, bands were detected as described above for PLUNC. Electrophoresis and immunoblotting of MUC5AC under these conditions is expected to produce a predominant band of ∼200 kDa (45).

RESULTS

Diversity of Proteins in BAL and ASL

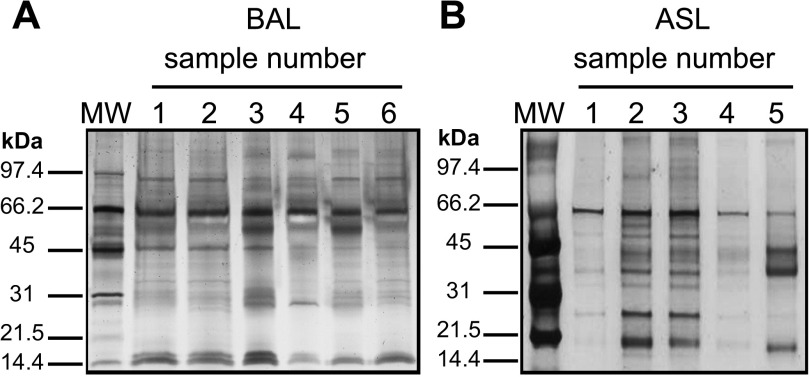

To investigate the composition of the lung lining fluid in the newborn pig, we sampled the alveolar subphase and the conducting airways by BAL as well as by direct collection of ASL from the trachea. The overall abundance and complexity of proteins in the BAL and ASL samples was assessed by separating proteins using SDS-PAGE and visualizing by silver stain. As shown in Fig. 2, both the BAL and ASL samples displayed a diverse complement of proteins across a wide range of molecular weights. Total protein concentrations were 0.050–0.42 mg/ml in newborn pig BAL samples and 5–15 mg/ml in ASL.

Fig. 2.

SDS-PAGE separation/silver staining of BAL and ASL proteins. A: BAL fluid from 6 individual newborn wild-type pigs, 2 μg protein/lane. B: ASL collected from 5 individual newborn wild-type pigs, 2 μg/lane. MW, molecular weight standard (SDS-PAGE Molecular Weight Standard, Low Range; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Shotgun Proteomics Detection of BAL Proteins

To better understand the composition of BAL, six samples were processed for LCMS analysis (as summarized in Fig. 1) using TFE for denaturation prior to trypsin digestion. To gain maximum coverage of the proteome, peptide mixtures were fractionated offline by two orthogonal methods, isoelectric focusing and alkaline pH reversed phase HPLC, prior to LCMS data acquisition. For the first two samples, a total of eight offline alkaline pH HPLC fractions were collected. The remaining BAL samples were more extensively fractionated for a total of 30 fractions. To maximize protein identification, spectra were searched against the pig Ensembl pep. all database, the superset of all translations resulting from Ensembl known or novel gene predictions. The general format of these entries was “ID Sequence type:Status:Location:Gene:Transcript.” To make this database useful for protein identification, we developed software to configure the header information for each protein to include the protein name, the gene name, and the source database. The annotated database is available for download at https://wiki.library.ucsf.edu/x/vSzWAw.

The number of proteins detected at ≤5% FDR in individual BAL samples ranged widely, from 46 to 558, with a total of 674 distinct proteins identified from all BAL samples (Table 1). More extensive fractionation at the peptide level prior to LCMS resulted in a significant increase in the number of peptides and proteins detected (BAL 1 and 2 vs. BAL 3–6). Over 89% of the proteins identified in the Ensembl database were mapped to porcine species-specific entries in Swiss-Prot, RefSeq, or TrEMBL (Supplemental Table S1; supplemental material for this article is available online at the Journal website). A sequence similarity search using BLAST (4) was performed for the 70 confidently detected sequences listed as “uncharacterized” or “novel transcript,” containing neither a protein name nor a gene name. For all but two proteins, very-high-scoring homologous sequences were identified (Supplemental Table S2).

Table 1.

Number of unique peptides and proteins detected in porcine BAL and ASL

| Sample | Distinct Peptides | Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| BAL1 | 826 | 119 |

| BAL2 | 149 | 46 |

| BAL3 | 4,096 | 384 |

| BAL4 | 3,898 | 161 |

| BAL5 | 4,270 | 422 |

| BAL6 | 4,957 | 558 |

| Master BAL | 9,313 | 674 |

| ASL1 | 3,513 | 1134 |

| ASL2 | 2,316 | 803 |

| ASL3 | 3,207 | 975 |

| ASL4 | 18,012 | 2,959 |

| ASL5 | 22,888 | 3,289 |

| Master ASL | 30,591 | 3,858 |

Data are presented for each individual bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and airway surface liquid (ASL) sample. Distinct peptides at the ≤1% global false discovery rate (FDR) and proteins with a ≤5% local FDR are shown. The “Master” search result of all BAL or ASL sample sets searched together was used to disambiguate the protein groups and align the proteins across data sets (Supplemental Tables S1 and S3).

As expected, the BAL dataset included many well-recognized lung gene products, such as α1-antitrypsin, the alveolar surfactant proteins [surfactant proteins B (SP-B) and C (SP-C)], and mucins such as MUC1 and MUC16 (Supplemental Table S1). Of interest, we identified numerous proteins associated with mammalian host defense, including lactoferrin, lipocalin 2, the collectins, SP-A and SP-D, the PLUNC protein and related family members, lactoperoxidase, S100-A8 (calgranulin-A) and S100-A9 (calgranulin-B), histones, and several components of the complement system. Additionally, we identified the pig-specific cathelicidin antimicrobial protein protegrin-1. Other proteins expected to be found in BAL, e.g., PR-39, PMAP-37, and the highly abundant MUC5AC and MUC5B, were not present in the Ensembl database. To verify the presence of these abundant BAL proteins in our samples, we searched the UniProt pig database, which contained full-length sequences for PR-39 and PMAP-37 and a partial sequence of MUC5AC (MUC5B was not in this database). PMAP-37 and MUC5AC were detected with multiple high-scoring peptides (Table 2). The relatively small size and high arginine content (10 of 39 amino acids) of PR-39 limited the number of observable tryptic peptides to one, which could explain why this abundant antimicrobial protein was not detected.

Table 2.

MUC5AC and PMAP-37 peptides that were used for protein identification

| Accession | Name | Coverage, % | Conf., % | Sequence | Cleavages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O97866 | MUC5AC (Fragment, 357 AA) | 56.9 | |||

| 99 | AESFPDTPLQALGQDVIC(CAM)DK | ||||

| 99 | WFDVDFPSPGPHGGDFETYSNILR | ||||

| 99 | LGQVVEC(CAM)RPEVGLVC(CAM)R | ||||

| P49932 | Antibacterial peptide PMAP-37 | 76.7 | |||

| 99 | AVDRLNEQSSEANLYR | Missed R-L@4 | |||

| 99 | LLELDQPPKADEDPGTPKPVSFTVK | Missed K-A@9 | |||

| 99 | LNEQSSEANLYR | ||||

| 99 | LLELDQPPK | ||||

| 96 | ADEDPGTPKPVSFTVK | ||||

| 99 | RPPELC(CAM)DFKEN(Dea)GR | W-R@N-term |

Mass spectrometry (MS) data from BAL samples were searched by using the pig Uniprot SwissProt and TrEMBL databases. Peptides detected with confidence levels ≥95% are shown. Coverage is the percent of matching amino acids (AAs) from identified peptides with any confidence (Conf.) divided by the total number of amino acids in the sequence. CAM, carbamidomethyl; Dea, deamidation; Cleavages, nontryptic cleavage sites.

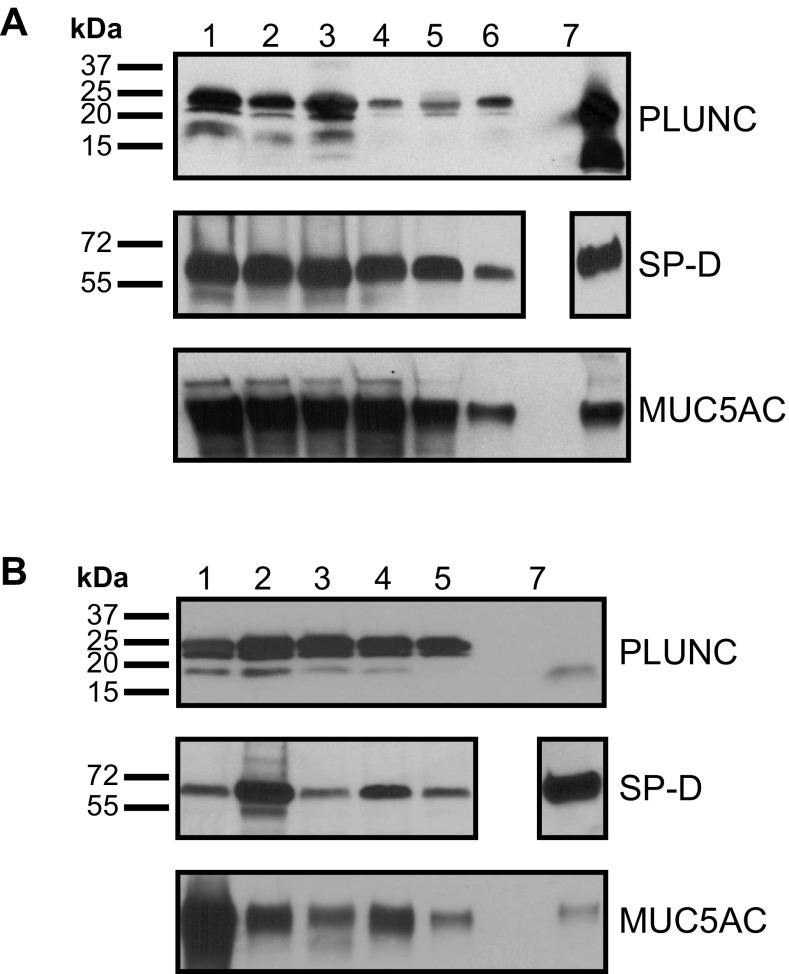

To independently verify our results, we selected a subset of BAL proteins (PLUNC, SP-D, and MUC5AC) to confirm by immunoblotting (Fig. 3). These proteins were selected for their known roles in the lung lining liquid milieu and the availability of cross-reacting antibodies. All BAL samples contained these proteins as determined by immunoblotting.

Fig. 3.

Verification of selected proteins identified in LC-MS/MS analysis. A: BAL fluid from wild-type newborn pigs was electrophoretically separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions (top and middle) and nonreducing conditions (bottom). Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes prior to immunoblotting with antisera specific for the PLUNC protein (top), surfactant protein-D (SP-D; middle), and MUC5AC (bottom). Lanes 1-6 contained lavage samples from 6 individual pigs. Secretions from the apical surface of pig primary airway epithelial cultures (2 μl) served as a positive control for the PLUNC antibody (lane 7). Recombinant porcine SP-D (50 ng) was a positive control for the SP-D antibody (lane 7; noncontiguous lane from the same blot). Total protein from pig stomach scraping (10 ng) served as a positive control for the MUC5AC antibody (lane 7). B: the strategy described for A was used for the immunoanalyses of 5 individual porcine ASL samples from wild-type newborn pigs.

ASL Protein Analysis

ASL from the conducting airways was harvested via a modified collection approach that was designed to avoid sampling the alveolar contribution. On the basis of experience gained with the BAL analysis, we refined our workflow as outlined in Fig. 1, using SDS as a denaturant with trypsin digestion in solution or on filters (55, 86). The number of distinct peptides identified was 6.5-fold higher with the in-solution trypsin digestion protocol, averaging 18,872, compared with 2,888 with the filter-assisted digestion protocol. This translated to an average of 2,407 protein groups compared with 969, respectively (Table 1). The presence of highly abundant glycosylated, difficult-to-proteolyze proteins in ASL could potentially clog the filter and reduce peptide recovery. Overall, the ASL analyses resulted in a significantly larger number of unique protein identifications compared with BAL, with 3,858 distinct proteins detected in toto (Supplemental Table S3). Confidently detected Ensembl sequences lacking a protein or gene name were searched by using BLAST as described for BAL proteins (Supplemental Table S4). Additional lung and host defense proteins detected in ASL included MUC-4, -13, and -19, LPLUNC2, lipocalin 1, antileukoproteinase (SLPI), PMAP-23, PLAT, protegrin 3, SPPI, and serpinB5. A subset of proteins (PLUNC, SP-D, and MUC5AC) was confirmed by immunoblotting and all ASL samples contained these proteins (Fig. 3B).

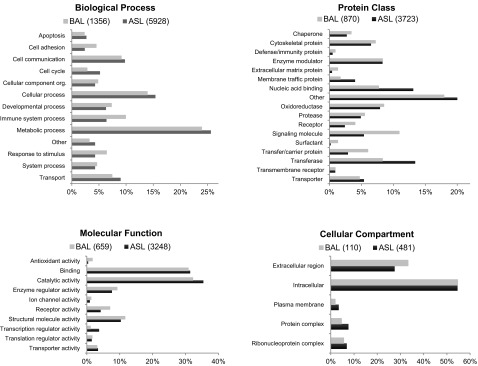

Functional Classification of BAL and ASL Proteins

We observed significant overlap between the BAL and ASL proteomes; 88% of BAL-associated proteins were also detected in ASL. Using PANTHER GO classifications, we categorized proteins in both datasets by biological process, protein class, molecular function, and cellular compartment (Fig. 4). The distribution of proteins was similar between BAL and ASL and included a broad range of protein classes associated with diverse processes such as responses to stimuli, immune system functions, cell communication, and transport. In addition to extracellular and secreted proteins, a number of intracellular proteins such as metabolic enzymes were identified.

Fig. 4.

Classifications for proteins identified in porcine BAL and ASL. Using PANTHER (80), we classified proteins by Gene Ontology terms describing biological process (A), protein class (B), molecular function (C), and cellular compartment (D). Results are displayed as percent of genes classified to a category over the total number of class hits. Class hit means independent ontology terms; if a gene was classified to more than 1 independent ontology terms that are not parent or child to each other, it counts as multiple class hits. The total number of class hits for each category is shown in parentheses after the sample type.

We previously profiled mRNA expression in trachea, bronchus tissue, and well-differentiated primary cultures of tracheal and bronchial epithelia isolated from wild-type and CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)-null newborn piglets (66). A set of 973 genes (secreted host defense proteins as well as those involved in inflammation, bacterial responses, and wounding) was compared with the proteins detected in BAL and ASL. A total of 314 proteins were found, 87 of which were secreted host defense proteins (Table 3).

Table 3.

Secreted host defense proteins detected in BAL and ASL

| Protein Identified in BAL/ASL | Gene from MicroArray | Protein Identified in BAL/ASL | Gene from MicroArray |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-2-macroglobulin | A2M | High mobility group protein B1 | HMGB1 |

| ATP-binding cassette F1 | ABCF1 | Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome 5 protein | HPS5 |

| RAGE Protein | AGER | 60-kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial | HSPD1 |

| Angiotensinogen | AGT | Interleukin-6 receptor subunit beta | IL6ST |

| Serum albumin | ALB | Integrin, beta 4 | ITGB4 |

| Protein AMBP | AMBP | Kininogen-1 | KNG1 |

| Annexin A1 | ANXA1 | Alpha-lactalbumin | LALBA |

| Annexin A5 | ANXA5 | Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein | LBP |

| Apolipoprotein A-I | APOA1 | Protein-lysine 6-oxidase | LOX |

| Apolipoprotein A-IV | APOA4 | Lactoperoxidase | LPO |

| Apolipoprotein E | APOE | Lactotransferrin | LTF |

| Beta-2-glycoprotein 1 | APOH | Lysozyme C-2 | LYSC2 |

| Beta-2-microglobulin | B2M | Lysozyme-like protein 6 | LYZL6 |

| Bactericidal permeability-increasing protein | BPI | Macrophage migration inhibitory factor | MIF |

| Complement C1r subcomponent | C1R | Growth/differentiation factor 8 | MSTN |

| C4b-binding protein alpha chain | C4BPA | Mucin 5AC | MUC5AC |

| Complement C5a anaphylatoxin | C5 | Tissue-type plasminogen activator | PLAT |

| Complement component C6 | C6 | Plasminogen | PLG |

| Complement component C7 | C7 | BPI fold-containing family A member 1 | PLUNC |

| Complement component C9 | C9 | Peroxiredoxin-5, mitochondrial | PRDX5 |

| Carbonic anhydrase 2 | CA2 | Vitamin K-dependent protein C | PROC |

| monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 | CD14 | Saposin-B-Val Saposin-B | PSAP |

| CD59 glycoprotein | CD59 | Protein S100-A8 | S100A8 |

| CD97 antigen | CD97 | Protein S100-A9 | S100A9 |

| Complement factor D | CFD | Serum amyloid A2 | SAA4 |

| Complement factor I | CFI | Alpha-1-antitrypsin | SERPINA1 |

| Properdin | CFP | Plasma serine protease inhibitor | SERPINA5 |

| Clusterin | CLU | Thyroxine-binding globulin | SERPINA7 |

| Cystatin-C | CST3 | Leukocyte elastase inhibitor | SERPINB1 |

| Cystatin-M | CST6 | Serpin B5 | SERPINB5 |

| Cystatin-B | CSTB | Heparin cofactor 2 | SERPIND1 |

| Lysosomal protective protein | CTSA | Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 | SERPINE1 |

| Cathepsin B | CTSB | alpha-2 antiplasmin member 1 | SERPINF1 |

| Cathepsin C | CTSC | alpha-2 antiplasmin member 2 | SERPINF2 |

| Procathepsin H | CTSH | Plasma protease C1 inhibitor | SERPING1 |

| Cathepsin L1 | CTSL1 | Pulmonary surfactant-associated protein D | SFTPD |

| Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor | CXADR | Superoxide dismutase | SOD1 |

| Acyl-CoA-binding protein DBI(32-86) | DBI | SPARC | SPARC |

| Epidermal growth factor | EGF | Osteopontin | SPP1 |

| Coagulation factor XII | F12 | Serotransferrin | TF |

| Coagulation factor V | F5 | Thyroglobulin | TG |

| Fibrinogen beta chain Fibrinopeptide B | FGB | Thrombospondin 1 | THBS1 |

| Fibronectin | FN1 | Tenascin | TNC |

| Fibronectin | FN1 | Vitronectin | VTN |

Proteins detected in BAL and ASL were cross referenced to a curated list of mRNA transcripts with recognized host defense and antimicrobial functions (66).

DISCUSSION

Here we developed techniques to identify proteins from the porcine lung and conducting airways by using BAL fluid and ASL as starting materials. To our knowledge, this study provides the most comprehensive database to date of proteins in porcine lung lining fluid. Because BAL has traditionally been the method of choice for sampling lung and airway secretions for proteomic studies, we began by characterizing BAL from newborn pigs. Although earlier studies used proteomics-based approaches to monitor pig BAL for changes in response to bacterial (33) and viral (88) pathogens, ours is the first attempt to compile the proteome of normal pig BAL, which resulted in the identification of 674 proteins. This level of detection was in line with previous reports that used mass spectrometry-based methods to identify BAL proteins in human (28, 44, 53, 58, 87), mouse (13, 17, 28, 31, 67), rat (74), cow (8), and horse (10). For example, Guo and colleagues (31) identified 297 proteins in BAL from a single mouse, and analysis of BAL from six healthy horses yielded 582 identifications (10). Notably, protein discovery has often been greatest in studies designed to investigate differential protein expression in the context of various pulmonary diseases or challenges. To date, the greatest number of BAL proteins reported for any species was 959, observed in a study investigating the effects of cigarette smoke inhalation in mice (67). In a study of biomarkers in lung transplant patients with chronic graft dysfunction, Kosanam et al. (44) reported a total of 531 proteins in human BAL. In another study, as many as 889 proteins were identified in BAL from antigen-challenged asthmatic patients and control individuals (87).

One drawback of using BAL fluid as the analyte for proteomics is that the collection technique necessarily involves significant and variable dilution, potentially complicating efforts to make quantitative comparisons among study subjects. As an alternative, several groups attempted to characterize lung lining fluid in humans using induced sputum, which can be collected without dilution of the sample (38, 60). We addressed this issue by collecting methacholine-induced tracheobronchial secretions directly from pig airways (ASL). We originally collected tracheal ASL using the capillary technique; however, it was not possible to collect sufficient material for MS analysis from individual animals. Although the composition of secretions with methacholine induction might be different than steady state, the proteins detected are those that the epithelium might release under resting conditions, or in response to neurohumoral or environmental stimuli (18, 19, 36, 40).

The number of protein identifications increased markedly when we shifted our focus from BAL samples to ASL. However, it is not clear whether the ASL samples are intrinsically more protein rich and diverse, or whether this is a consequence of refinements in our methods of sample collection and preparation, peptide fractionation, and/or LCMS instrumentation, making a direct comparison of the data difficult. For example, increasing the number of BAL peptide fractions analyzed from 8 to 30 resulted in an average 4.5-fold increase in protein identifications on the QSTAR Elite. Although fewer ASL fractions (n = 20) were analyzed, more proteins were detected by using the LTQ Orbitrap Velos. It is not possible to determine how much of this effect was due to the MS platform or inherent to the sample type. We note that both instruments undergo quality control measures assuring 1 fmol protein digest sensitivity. A confounding factor in the analysis of lung lining fluids is the presence of highly abundant proteins (e.g., albumin, serotransferrin, α2-macroglobulin, α1-acid glycoprotein) that contribute to the dynamic range of these complex mixtures and confound detection of medium- and low-abundance species. Affinity-depletion strategies have been used to ameliorate this issue in human BAL, although no pig-specific antibodies are currently available for this purpose. We found that 88% of the proteins detected in BAL were also found in ASL. However, since other studies have reported ∼900 proteins in BAL (67, 87), the overlap of common proteins in these fluids could be greater. We speculate that avoidance of the sample dilution associated with BAL collection may have enhanced the number of proteins detected. In addition to minimizing sample dilution, this approach also afforded the opportunity to investigate the protein repertoire of the tracheobronchial epithelium, representative of the conducting airways, separately from the alveolar compartment. Although this sampling technique appears to be unique to our study, other investigators have attempted to examine the composition of ASL by using mass spectrometry to identify proteins in apical secretions from air-liquid interface cultures of human primary airway epithelia (3, 12, 38) or cell lines (37).

In the course of these experiments, we optimized database searching methods for identification of proteins in pig-derived samples. A critical factor was selection of the protein database. The porcine protein databases still have large gaps, although the number of entries is increasing monthly due to continued progress on the pig genome (30). The UniProt Knowledgebase (KB) version used in this study contained only 1,406 manually curated, nonredundant (SwissProt) entries for Sus scrofa proteins, compared with 20,248 entries in the human and 65,102 in the mammalian databases (54). To overcome the paucity of fully annotated entries, MS data from porcine samples are often searched against either human plus pig or mammalian protein databases (6, 35, 56, 70). An additional UniProtKB database, TrEMBL, contains protein sequences associated with computationally generated annotation but is not reviewed nor curated for redundancy. Protein fragments, isoforms and variants, encoded by the same gene, are found in separate entries. We annotated the 23,118 Ensembl Sus scrofa 10.2.67.pep. all database entries with protein name, gene name, and source database. Then we compiled databases that contained various combinations of the curated and noncurated pig and mammalian entries and tested various search parameters to determine the optimal strategy for identifying the greatest number of proteins with low FDRs for peptide and protein detection. In summary, searching the Ensembl Sus scrofa protein FASTA database explained the greatest number of spectra at a given FDR and reduced the number of redundant proteins found compared with searching the larger mammalian databases. We detected many pig peptides and proteins whose existence was previously only predicted from available genomic (DNA) and transcriptomic (mRNA, EST) data. The Ensembl protein database is not complete, and we noted that some known lung proteins, such as the mucins MUC5AC and MUC5B as well as the pig-specific antimicrobial proteins PR-39 and PMAP-37, are not present. However, MUC5AC and PMAP-37 were identified in BAL and ASL by using the pig UniProt SwissProt and TrEMBL. The abundant MUC5B, which has been detected on the luminal surface of the bronchiolar epithelium of piglets airways by using immunohistochemistry (41), is not present in any of the porcine protein databases thus precluding MS-based identification in these data sets.

The most abundant proteins in both the BAL and ASL datasets included plasma proteins: serotransferrin, serum albumin, complement factor C3, α2-HS-glycoprotein (fetuin-A), α-fetoprotein, α1-acid glycoprotein 1, α2-macroglobulin, immunoglobulins, fetuin-B, and haptoglobin. In this respect, our study is in very good agreement with earlier proteomic analyses, which consistently reported plasma proteins in BAL and other airway fluids (14, 28, 44, 47, 48, 50, 53, 58, 83, 84, 87). This finding may reflect physiological transudates of plasma proteins from the circulation into the airways or alveoli and/or may be due to low level blood contamination introduced during sample collection procedures. However, there is also evidence that at least some of these proteins are normal secretory products of airway epithelia. Proteomic studies of apical secretions from cultured human airway epithelia have documented release of complement factor C3, α2-macroglobulin, α2-HS-glycoprotein, and serum albumin from these cells (3, 12, 38).

As shown in Fig. 4, we found that the proteins detected in BAL and ASL were similarly distributed across protein classes, biological processes, and molecular functions. Interestingly, the largest proportion (∼25%) of proteins in both sample types was categorized as having a role in metabolic processes, likely reflecting the fact that a significant proportion of the detected proteins was predicted to be cytoplasmic or intracellular. The detection of intracellular proteins has been noted in earlier studies of airway secretions (3, 12, 38, 87). It is possible that some of these proteins may be derived from apoptotic cells, the result of normal turnover of airway epithelium, or possibly from cell debris due to disruption of the epithelium during sample collection. However, a review of the literature suggests that a certain number of intracellular proteins might actually be expected in the lung lining fluid of mammals, due to the secretory machinery of the airway epithelium and submucosal glands. Studies in humans, mice, and rabbits have provided evidence for both merocrine and apocrine secretion by goblet cells of the airway epithelium (and Clara cells in mice) (26, 42, 63, 64, 73). In merocrine secretion, secretory products are packaged into vesicles and exocytosed directly to the extracellular milieu; apocrine secretion involves release of cargo as part of membrane-bound vesicles that bud off the apical surface of the cell. Thus it is anticipated that apocrine secretion could result in disruption of cell membranes and introduction of intracellular and membrane proteins into the ASL. In support of this possibility, a recent proteomic study demonstrated that membrane-bound granules secreted from airway epithelial goblet cells contain cytoskeletal and regulatory proteins as well as mucins, suggesting that such granules may be a source for some of the intracellular proteins detected in ASL (69). Additionally, several groups have reported the presence of exosomes, microvesicles implicated in host defense and cell communication, in human BAL and cell culture secretions (1, 39). Exosomes have been shown to be associated with mucins, cytoskeletal proteins, and cytosolic enzymes, suggesting that these structures may also be a source of some of the intracellular proteins we identified.

Among the lung lining liquid (BAL and ASL) proteins identified were many associated with host defense (Supplemental Tables S1 and S3), including histone fragments, lactoferrin, lactoperoxidase, lysozyme, lipocalin 1, lipocalin 2, PLUNC, LPLUNC1, LPLUNC2, SLPI, surfactant proteins A and D, S100A8 (calgranulin-A), S100A9 (calgranulin-B), and the pig-specific antimicrobial cathelicidin proteins (PMAP-23, PMAP-37) and protegrins-1 and -3. It is also interesting to note that several proteins of the complement family were present in lung lining liquid. These included complement components (C1r, C4, CB, C5, C6, C7, C9) and complement factors (B, D, H, and I). The complement system is recognized for its roles in innate immunity, with activities that include opsonization, chemotaxis, and membrane destruction. However, the functions of complement protein components in lung lining liquid are not well studied. Several protease inhibitors (e.g., the serine protease inhibitors, serpins) and proteases (e.g., the cathepsins) were also resident in lung lining liquid. This speaks to the importance of a balance of these forces in modulating protein function. Mucociliary clearance is an important component of airway host defenses, and both tethered and secreted components of the mucin layer were identified, including Muc1, -2, -3A, -4, -5AC, -13, -16, and -19. Our data focus on an important early time point after birth. Thus the BAL and ASL proteome may change over time as the animal develops.

In summary, this study is the first to define the proteome of the lung lining fluid in the newborn pig. For this task, we used both BAL fluid as well as methacholine-stimulated tracheal secretions in an effort to ensure that our results encompass both the conducting airways and the gas-exchange regions of the lung. In doing so, we greatly expanded the known proteome of the porcine lung, while also contributing to the greater body of literature documenting the composition of airway secretions across all mammalian species. Our database of porcine airway proteins should provide a framework for future studies utilizing porcine models of airway infection, disease, or injury. In particular, it can serve as a reference for proteomic studies of pathogenesis and/or progressive lung changes in porcine models of CF and other inflammatory lung conditions. Additionally, these findings may also be useful for studies investigating responses to economically relevant pig pathogens such as porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome and influenza. Thus this “pig airway proteome” is a resource that will enhance the utility of the pig as an animal model for studies of lung biology, disease, and therapeutics.

GRANTS

We acknowledge support from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation RDP (P. B. McCray and S. J. Fisher), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants P50 HL-61234 (P. B. McCray) and P01 HL-091842 (P. B. McCray), as well as the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust (P. B. McCray). The UCSF Sandler-Moore Mass Spectrometry Core Facility is partially funded by a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant, the Sandler Family Foundation, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

At the request of the author(s), readers are herein alerted to the fact that additional materials related to this manuscript may be found at the institutional website of one of the authors, which at the time of publication is https://wiki.library.ucsf.edu/x/vSzWAw. These materials are not a part of this manuscript and have not undergone peer review by the American Physiological Society (APS). APS and the journal editors take no responsibility for these materials, for the website address, or for any links to or from it.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.A.B., J.Z., S.J.F., P.B.M., and K.E.W. conception and design of research; J.A.B., M.E.A., C.W.-L., A.A.P., and K.E.W. performed experiments; J.A.B., M.E.A., R.K.N., and K.E.W. analyzed data; J.A.B., P.B.M., and K.E.W. interpreted results of experiments; J.A.B., M.E.A., and K.E.W. prepared figures; J.A.B., P.B.M., and K.E.W. drafted manuscript; J.A.B., S.J.F., P.B.M., and K.E.W. edited and revised manuscript; J.A.B., M.E.A., C.W.-L., A.A.P., J.Z., R.K.N., S.J.F., P.B.M., and K.E.W. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Paula Ludwig for technical support. Polyclonal antiserum against porcine SP-D was generously provided by Dr. Henk Haagsman (Utrecht University, The Netherlands).

REFERENCES

- 1. Admyre C, Grunewald J, Thyberg J, Gripenback S, Tornling G, Eklund A, Scheynius A, Gabrielsson S. Exosomes with major histocompatibility complex class II and co-stimulatory molecules are present in human BAL fluid. Eur Respir J 22: 578–583, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alho HS, Maasilta PK, Vainikka T, Salminen US. Platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor-beta, and connective tissue growth factor in a porcine bronchial model of obliterative bronchiolitis. Exp Lung Res 33: 303–320, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ali M, Lillehoj EP, Park Y, Kyo Y, Kim KC. Analysis of the proteome of human airway epithelial secretions. Proteome Sci 9: 4, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215: 403–410, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ballard ST, Inglis SK. Liquid secretion properties of airway submucosal glands. J Physiol 556: 1–10, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barallobre-Barreiro J, Didangelos A, Schoendube FA, Drozdov I, Yin X, Fernandez-Caggiano M, Willeit P, Puntmann VO, Aldama-Lopez G, Shah AM, Domenech N, Mayr M. Proteomics analysis of cardiac extracellular matrix remodeling in a porcine model of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation 125: 789–802, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bartlett JA, Fischer AJ, McCray PB., Jr Innate immune functions of the airway epithelium. Contrib Microbiol 15: 147–163, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boehmer JL, Degrasse JA, Lancaster VA, McFarland MA, Callahan JH, Ward JL. Evaluation of protein expression in bovine bronchoalveolar fluid following challenge with Mannheimia haemolytica. Proteomics 11: 3685–3697, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brandler MD, Powell SC, Craig DM, Quick G, McMahon TJ, Goldberg RN, Stamler JS. A novel inhaled organic nitrate that affects pulmonary vascular tone in a piglet model of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Pediatr Res 58: 531–536, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bright LA, Mujahid N, Nanduri B, McCarthy FM, Costa LR, Burgess SC, Swiderski CE. Functional modelling of an equine bronchoalveolar lavage fluid proteome provides experimental confirmation and functional annotation of equine genome sequences. Anim Genet 42: 395–405, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Budas GR, Churchill EN, Mochly-Rosen D. Cardioprotective mechanisms of PKC isozyme-selective activators and inhibitors in the treatment of ischemia-reperfusion injury. Pharm Res 55: 523–536, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Candiano G, Bruschi M, Pedemonte N, Musante L, Ravazzolo R, Liberatori S, Bini L, Galietta LJ, Zegarra-Moran O. Proteomic analysis of the airway surface liquid: modulation by proinflammatory cytokines. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292: L185–L198, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang CC, Chen SH, Ho SH, Yang CY, Wang HD, Tsai ML. Proteomic analysis of proteins from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid reveals the action mechanism of ultrafine carbon black-induced lung injury in mice. Proteomics 7: 4388–4397, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen J, Ryu S, Gharib SA, Goodlett DR, Schnapp LM. Exploration of the normal human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid proteome. Proteomics Clin Appl 2: 585–595, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen JH, Stoltz DA, Karp PH, Ernst SE, Pezzulo AA, Moninger TO, Rector MV, Reznikov LR, Launspach JL, Chaloner K, Zabner J, Welsh MJ. Loss of anion transport without increased sodium absorption characterizes newborn porcine cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. Cell 143: 911–923, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chenau J, Michelland S, Sidibe J, Seve M. Peptides OFFGEL electrophoresis: a suitable pre-analytical step for complex eukaryotic samples fractionation compatible with quantitative iTRAQ labeling. Proteome Sci 6: 9, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chiu KH, Lee WL, Chang CC, Chen SC, Chang YC, Ho MN, Hsu JF, Liao PC. A label-free differential proteomic analysis of mouse bronchoalveolar lavage fluid exposed to ultrafine carbon black. Anal Chim Acta 673: 160–166, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cho HJ, Joo NS, Wine JJ. Defective fluid secretion from submucosal glands of nasal turbinates from CFTR−/− and CFTR (DeltaF508/DeltaF508) pigs. PLoS One 6: e24424, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cooper JL, Quinton PM, Ballard ST. Mucociliary transport in porcine trachea: differential effects of inhibiting chloride and bicarbonate secretion. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 304: L184–L190, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cunningham S, Meng QH, Klein N, McAnulty RJ, Hart SL. Evaluation of a porcine model for pulmonary gene transfer using a novel synthetic vector. J Gene Med 4: 438–446, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Delmotte P, Sanderson MJ. Effects of albuterol isomers on the contraction and Ca2+ signaling of small airways in mouse lung slices. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 38: 524–531, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dowell JA, Frost DC, Zhang J, Li L. Comparison of two-dimensional fractionation techniques for shotgun proteomics. Anal Chem 80: 6715–6723, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Durairaj L, Neelakantan S, Launspach J, Watt JL, Allaman MM, Kearney WR, Veng-Pedersen P, Zabner J. Bronchoscopic assessment of airway retention time of aerosolized xylitol. Respir Res 7: 27, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dwivedi RC, Spicer V, Harder M, Antonovici M, Ens W, Standing KG, Wilkins JA, Krokhin OV. Practical implementation of 2D HPLC scheme with accurate peptide retention prediction in both dimensions for high-throughput bottom-up proteomics. Anal Chem 80: 7036–7042, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ernoult E, Bourreau A, Gamelin E, Guette C. A proteomic approach for plasma biomarker discovery with iTRAQ labelling and OFFGEL fractionation. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010: 927917, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Etherton JE, Purchase IF, Corrin B. Apocrine secretion in the terminal bronchiole of mouse lung. J Anat 129: 305–322, 1979. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gauger PC, Vincent AL, Loving CL, Henningson JN, Lager KM, Janke BH, Kehrli ME, Jr, Roth JA. Kinetics of lung lesion development and pro-inflammatory cytokine response in pigs with vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory disease induced by challenge with pandemic (2009) A/H1N1 influenza virus. Vet Pathol 49: 900–912, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gharib SA, Nguyen E, Altemeier WA, Shaffer SA, Doneanu CE, Goodlett DR, Schnapp LM. Of mice and men: comparative proteomics of bronchoalveolar fluid. Eur Respir J 35: 1388–1395, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Glenny R, Bernard S, Neradilek B, Polissar N. Quantifying the genetic influence on mammalian vascular tree structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 6858–6863, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Groenen MA, Archibald AL, Uenishi H, Tuggle CK, Takeuchi Y, Rothschild MF, Rogel-Gaillard C, Park C, Milan D, Megens HJ, Li S, Larkin DM, Kim H, Frantz LA, Caccamo M, Ahn H, Aken BL, Anselmo A, Anthon C, Auvil L, Badaoui B, Beattie CW, Bendixen C, Berman D, Blecha F, Blomberg J, Bolund L, Bosse M, Botti S, Bujie Z, Bystrom M, Capitanu B, Carvalho-Silva D, Chardon P, Chen C, Cheng R, Choi SH, Chow W, Clark RC, Clee C, Crooijmans RP, Dawson HD, Dehais P, De Sapio F, Dibbits B, Drou N, Du ZQ, Eversole K, Fadista J, Fairley S, Faraut T, Faulkner GJ, Fowler KE, Fredholm M, Fritz E, Gilbert JG, Giuffra E, Gorodkin J, Griffin DK, Harrow JL, Hayward A, Howe K, Hu ZL, Humphray SJ, Hunt T, Hornshoj H, Jeon JT, Jern P, Jones M, Jurka J, Kanamori H, Kapetanovic R, Kim J, Kim JH, Kim KW, Kim TH, Larson G, Lee K, Lee KT, Leggett R, Lewin HA, Li Y, Liu W, Loveland JE, Lu Y, Lunney JK, Ma J, Madsen O, Mann K, Matthews L, McLaren S, Morozumi T, Murtaugh MP, Narayan J, Nguyen DT, Ni P, Oh SJ, Onteru S, Panitz F, Park EW, Park HS, Pascal G, Paudel Y, Perez-Enciso M, Ramirez-Gonzalez R, Reecy JM, Rodriguez-Zas S, Rohrer GA, Rund L, Sang Y, Schachtschneider K, Schraiber JG, Schwartz J, Scobie L, Scott C, Searle S, Servin B, Southey BR, Sperber G, Stadler P, Sweedler JV, Tafer H, Thomsen B, Wali R, Wang J, Wang J, White S, Xu X, Yerle M, Zhang G, Zhang J, Zhang J, Zhao S, Rogers J, Churcher C, Schook LB. Analyses of pig genomes provide insight into porcine demography and evolution. Nature 491: 393–398, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guo Y, Ma SF, Grigoryev D, Van Eyk J, Garcia JG. 1-DE MS and 2-D LC-MS analysis of the mouse bronchoalveolar lavage proteome. Proteomics 5: 4608–4624, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gushima Y, Ichikado K, Suga M, Okamoto T, Iyonaga K, Sato K, Miyakawa H, Ando M. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases in pigs with hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury. Eur Respir J 18: 827–837, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hennig-Pauka I, Jacobsen I, Blecha F, Waldmann KH, Gerlach GF. Differential proteomic analysis reveals increased cathelicidin expression in porcine bronchoalveolar lavage fluid after an Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae infection. Vet Res 37: 75–87, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hubner NC, Ren S, Mann M. Peptide separation with immobilized pI strips is an attractive alternative to in-gel protein digestion for proteome analysis. Proteomics 8: 4862–4872, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jiang P, Sangild PT, Siggers RH, Sit WH, Lee CL, Wan JM. Bacterial colonization affects the intestinal proteome of preterm pigs susceptible to necrotizing enterocolitis. Neonatology 99: 280–288, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Joo NS, Cho HJ, Khansaheb M, Wine JJ. Hyposecretion of fluid from tracheal submucosal glands of CFTR-deficient pigs. J Clin Invest 120: 3161–3166, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Joo NS, Lee DJ, Winges KM, Rustagi A, Wine JJ. Regulation of antiprotease and antimicrobial protein secretion by airway submucosal gland serous cells. J Biol Chem 279: 38854–38860, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kesimer M, Kirkham S, Pickles RJ, Henderson AG, Alexis NE, Demaria G, Knight D, Thornton DJ, Sheehan JK. Tracheobronchial air-liquid interface cell culture: a model for innate mucosal defense of the upper airways? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 296: L92–L100, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kesimer M, Scull M, Brighton B, DeMaria G, Burns K, O'Neal W, Pickles RJ, Sheehan JK. Characterization of exosome-like vesicles released from human tracheobronchial ciliated epithelium: a possible role in innate defense. FASEB J 23: 1858–1868, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Khansaheb M, Choi JY, Joo NS, Yang YM, Krouse M, Wine JJ. Properties of substance P-stimulated mucus secretion from porcine tracheal submucosal glands. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 300: L370–L379, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim CH, Oh Y, Han K, Seo HW, Kim D, Park C, Kang I, Chae C. Expression of secreted and membrane-bound mucins in the airways of piglets experimentally infected with Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Vet J 192: 120–122, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Klinger JD, Tandler B, Liedtke CM, Boat TF. Proteinases of Pseudomonas aeruginosa evoke mucin release by tracheal epithelium. J Clin Invest 74: 1669–1678, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klymiuk N, Mundhenk L, Kraehe K, Wuensch A, Plog S, Emrich D, Langenmayer MC, Stehr M, Holzinger A, Kroner C, Richter A, Kessler B, Kurome M, Eddicks M, Nagashima H, Heinritzi K, Gruber AD, Wolf E. Sequential targeting of CFTR by BAC vectors generates a novel pig model of cystic fibrosis. J Mol Med (Berl) 90: 597–608, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kosanam H, Sato M, Batruch I, Smith C, Keshavjee S, Liu M, Diamandis EP. Differential proteomic analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from lung transplant patients with and without chronic graft dysfunction. Clin Biochem 45: 223–230, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lacunza E, Bara J, Segal-Eiras A, Croce MV. Expression of conserved mucin domains by epithelial tissues in various mammalian species. Res Vet Sci 86: 68–77, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lehtola A, Harjula A, Heikkila L, Hammainen P, Taskinen E, Kurki T, Mattila S. Single-lung allotransplantation in pigs following donor pretreatment with intravenous prostaglandin E-1. Morphologic changes after preservation and reperfusion. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 23: 193–199, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lindahl M, Ekstrom T, Sorensen J, Tagesson C. Two dimensional protein patterns of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from non-smokers, smokers, and subjects exposed to asbestos. Thorax 51: 1028–1035, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lindahl M, Stahlbom B, Svartz J, Tagesson C. Protein patterns of human nasal and bronchoalveolar lavage fluids analyzed with two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 19: 3222–3229, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lindahl M, Stahlbom B, Tagesson C. Identification of a new potential airway irritation marker, palate lung nasal epithelial clone protein, in human nasal lavage fluid with two-dimensional electrophoresis and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight. Electrophoresis 22: 1795–1800, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lindahl M, Stahlbom B, Tagesson C. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of nasal and bronchoalveolar lavage fluids after occupational exposure. Electrophoresis 16: 1199–1204, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Loving CL, Vincent AL, Pena L, Perez DR. Heightened adaptive immune responses following vaccination with a temperature-sensitive, live-attenuated influenza virus compared with adjuvanted, whole-inactivated virus in pigs. Vaccine 30: 5830–5838, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Macris MP, Nakatani T, Myers TJ, Lammermeier DE, Igo SR, Frazier OH, Cooley DA. An experimental technique for heart-lung transplantation in subprimate models. Tex Heart Inst J 17: 228–233, 1990. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Magi B, Bini L, Perari MG, Fossi A, Sanchez JC, Hochstrasser D, Paesano S, Raggiaschi R, Santucci A, Pallini V, Rottoli P. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid protein composition in patients with sarcoidosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a two-dimensional electrophoretic study. Electrophoresis 23: 3434–3444, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Magrane M, UniProt Consortium UniProt Knowledgebase: a hub of integrated protein data. Database (Oxford) 2011: bar009, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Manza LL, Stamer SL, Ham AJ, Codreanu SG, Liebler DC. Sample preparation and digestion for proteomic analyses using spin filters. Proteomics 5: 1742–1745, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Martins RP, Collado-Romero M, Martinez-Gomariz M, Carvajal A, Gil C, Lucena C, Moreno A, Garrido JJ. Proteomic analysis of porcine mesenteric lymph-nodes after Salmonella typhimurium infection. J Proteomics 75: 4457–4470, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Martins S, de Perrot M, Imai Y, Yamane M, Quadri SM, Segall L, Dutly A, Sakiyama S, Chaparro A, Davidson BL, Waddell TK, Liu M, Keshavjee S. Transbronchial administration of adenoviral-mediated interleukin-10 gene to the donor improves function in a pig lung transplant model. Gene Ther 11: 1786–1796, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Merkel D, Rist W, Seither P, Weith A, Lenter MC. Proteomic study of human bronchoalveolar lavage fluids from smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by combining surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry profiling with mass spectrometric protein identification. Proteomics 5: 2972–2980, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nazari S, Prati U, Berti A, Hoffmann JW, Moncalvo F, Zonta A. Successful bronchial revascularization in experimental single lung transplantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 4: 561–566; discussion 567, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Nicholas B, Skipp P, Mould R, Rennard S, Davies DE, O'Connor CD, Djukanovic R. Shotgun proteomic analysis of human-induced sputum. Proteomics 6: 4390–4401, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Opriessnig T, Xiao CT, Gerber PF, Halbur PG. Emergence of a novel mutant PCV2b variant associated with clinical PCVAD in two vaccinated pig farms in the U. S. concurrently infected with PPV2. Vet Microbiol 163: 177–183, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ostedgaard LS, Meyerholz DK, Chen JH, Pezzulo AA, Karp PH, Rokhlina T, Ernst SE, Hanfland RA, Reznikov LR, Ludwig PS, Rogan MP, Davis GJ, Dohrn CL, Wohlford-Lenane C, Taft PJ, Rector MV, Hornick E, Nassar BS, Samuel M, Zhang Y, Richter SS, Uc A, Shilyansky J, Prather RS, McCray PB, Jr, Zabner J, Welsh MJ, Stoltz DA. The ΔF508 mutation causes CFTR misprocessing and cystic fibrosis-like disease in pigs. Sci Transl Med 3: 74ra24, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pack RJ, Al-Ugaily LH, Morris G. The cells of the tracheobronchial epithelium of the mouse: a quantitative light and electron microscope study. J Anat 132: 71–84, 1981. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pack RJ, Al-Ugaily LH, Morris G, Widdicombe JG. The distribution and structure of cells in the tracheal epithelium of the mouse. Cell Tissue Res 208: 65–84, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Park C, Oh Y, Seo HW, Han K, Chae C. Comparative effects of vaccination against porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) in a PCV2-PRRSV challenge model. Clin Vaccine Immunol 20: 369–376, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Pezzulo AA, Tang XX, Hoegger MJ, Alaiwa MH, Ramachandran S, Moninger TO, Karp PH, Wohlford-Lenane CL, Haagsman HP, van Eijk M, Banfi B, Horswill AR, Stoltz DA, McCray PB, Jr, Welsh MJ, Zabner J. Reduced airway surface pH impairs bacterial killing in the porcine cystic fibrosis lung. Nature 487: 109–113, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pounds JG, Flora JW, Adkins JN, Lee KM, Rana GS, Sengupta T, Smith RD, McKinney WJ. Characterization of the mouse bronchoalveolar lavage proteome by micro-capillary LC-FTICR mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 864: 95–101, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Qian WJ, Liu T, Monroe ME, Strittmatter EF, Jacobs JM, Kangas LJ, Petritis K, Camp DG, 2nd, Smith RD. Probability-based evaluation of peptide and protein identifications from tandem mass spectrometry and SEQUEST analysis: the human proteome. J Proteome Res 4: 53–62, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Raiford KL, Park J, Lin KW, Fang S, Crews AL, Adler KB. Mucin granule-associated proteins in human bronchial epithelial cells: the airway goblet cell “granulome.” Respir Res 12: 118, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ramirez-Boo M, Garrido JJ, Ogueta S, Calvete JJ, Gomez-Diaz C, Moreno A. Analysis of porcine peripheral blood mononuclear cells proteome by 2-DE and MS: analytical and biological variability in the protein expression level and protein identification. Proteomics 6, Suppl 1: S215–S225, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rogers CS, Abraham WM, Brogden KA, Engelhardt JF, Fisher JT, McCray PB, Jr, McLennan G, Meyerholz DK, Namati E, Ostedgaard LS, Prather RS, Sabater JR, Stoltz DA, Zabner J, Welsh MJ. The porcine lung as a potential model for cystic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L240–L263, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rogers CS, Stoltz DA, Meyerholz DK, Ostedgaard LS, Rokhlina T, Taft PJ, Rogan MP, Pezzulo AA, Karp PH, Itani OA, Kabel AC, Wohlford-Lenane CL, Davis GJ, Hanfland RA, Smith TL, Samuel M, Wax D, Murphy CN, Rieke A, Whitworth K, Uc A, Starner TD, Brogden KA, Shilyansky J, McCray PB, Jr, Zabner J, Prather RS, Welsh MJ. Disruption of the CFTR gene produces a model of cystic fibrosis in newborn pigs. Science 321: 1837–1841, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Rogers DF. Airway goblet cells: responsive and adaptable front-line defenders. Eur Respir J 7: 1690–1706, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Signor L, Tigani B, Beckmann N, Falchetto R, Stoeckli M. Two-dimensional electrophoresis protein profiling and identification in rat bronchoalveolar lavage fluid following allergen and endotoxin challenge. Proteomics 4: 2101–2110, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Siu KW, DeSouza LV, Scorilas A, Romaschin AD, Honey RJ, Stewart R, Pace K, Youssef Y, Chow TF, Yousef GM. Differential protein expressions in renal cell carcinoma: new biomarker discovery by mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res 8: 3797–3807, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sommerer D, Suss R, Hammerschmidt S, Wirtz H, Arnold K, Schiller J. Analysis of the phospholipid composition of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid from man and minipig by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in combination with TLC. J Pharm Biomed Anal 35: 199–206, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Stoltz DA, Meyerholz DK, Pezzulo AA, Ramachandran S, Rogan MP, Davis GJ, Hanfland RA, Wohlford-Lenane CL, Dohrn CL, Bartlett JA, Nelson GA, Chang EH, Taft PJ, Ludwig PS, Estin M, Hornick EE, Launspach JL, Samuel M, Rokhlina T, Karp PH, Ostedgaard LS, Uc A, Starner TD, Horswill AR, Brogden KA, Prather RS, Richter SR, Shilyansky J, McCray PB, Jr, Zabner J, Welsh MJ. Cystic fibrosis pigs develop lung disease and exhibit defective bacterial eradication at birth. Sci Transl Med 2: 29ra31, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Tambor V, Hunter CL, Seymour SL, Kacerovsky M, Stulik J, Lenco J. CysTRAQ — a combination of iTRAQ and enrichment of cysteinyl peptides for uncovering and quantifying hidden proteomes. J Proteomics 75: 857–867, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Tang WH, Shilov IV, Seymour SL. Nonlinear fitting method for determining local false discovery rates from decoy database searches. J Proteome Res 7: 3661–3667, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Thomas PD, Kejariwal A, Campbell MJ, Mi H, Diemer K, Guo N, Ladunga I, Ulitsky-Lazareva B, Muruganujan A, Rabkin S, Vandergriff JA, Doremieux O. PANTHER: a browsable database of gene products organized by biological function, using curated protein family and subfamily classification. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 334–341, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wang H, Qian WJ, Mottaz HM, Clauss TR, Anderson DJ, Moore RJ, Camp DG, 2nd, Khan AH, Sforza DM, Pallavicini M, Smith DJ, Smith RD. Development and evaluation of a micro- and nanoscale proteomic sample preparation method. J Proteome Res 4: 2397–2403, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Watremez C, Liistro G, deKock M, Roeseler J, Clerbaux T, Detry B, Reynaert M, Gianello P, Jolliet P. Effects of helium-oxygen on respiratory mechanics, gas exchange, and ventilation-perfusion relationships in a porcine model of stable methacholine-induced bronchospasm. Intensive Care Med 29: 1560–1566, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Wattiez R, Hermans C, Bernard A, Lesur O, Falmagne P. Human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid: two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, amino acid microsequencing and identification of major proteins. Electrophoresis 20: 1634–1645, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Wattiez R, Hermans C, Cruyt C, Bernard A, Falmagne P. Human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid protein two-dimensional database: study of interstitial lung diseases. Electrophoresis 21: 2703–2712, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Wine JJ, Joo NS. Submucosal glands and airway defense. Proc Am Thorac Soc 1: 47–53, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wisniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat Methods 6: 359–362, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Wu J, Kobayashi M, Sousa EA, Liu W, Cai J, Goldman SJ, Dorner AJ, Projan SJ, Kavuru MS, Qiu Y, Thomassen MJ. Differential proteomic analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in asthmatics following segmental antigen challenge. Mol Cell Proteomics 4: 1251–1264, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Xiao S, Wang Q, Jia J, Cong P, Mo D, Yu X, Qin L, Li A, Niu Y, Zhu K, Wang X, Liu X, Chen Y. Proteome changes of lungs artificially infected with H-PRRSV and N-PRRSV by two-dimensional fluorescence difference gel electrophoresis. Virol J 7: 107, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Zhao J, Zhu H, Wong CH, Leung KY, Wong WS. Increased lungkine and chitinase levels in allergic airway inflammation: a proteomics approach. Proteomics 5: 2799–2807, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.