Abstract

The therapeutic potential of human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells, especially human adipose tissue-derived stem cells (hASC), is promising. However, there are concerns about the safety of infusion of hASC in human. Recently, we have experienced pulmonary embolism and infarct among family members who have taken multiple infusions of intravenous autologous hASC therapy. A 41-year-old man presented with chest pain for one month. Chest CT showed multiple pulmonary artery embolism and infarct at right lung. Serum D-dimer was 0.8 µg/mL (normal; 0-0.5 µg/mL). He had received intravenous autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cell therapy for cervical herniated intervertebral disc three times (one, two, and three months prior to the visit). His parents also received the same therapy five times and their chest CT also showed multiple pulmonary embolism. These cases represent artificial pulmonary embolisms and infarct after IV injection of hASC. Follow-up chest CT showed spontaneous resolution of lesions in all three patients.

Keywords: Stem cell, pulmonary embolism, infarct, family

INTRODUCTION

The most common application of stem cell therapy in medicine is to replace cell lines that have been lost or destroyed.1 Adult human adipose tissue originates from the embryonic mesoderm, and represents an abundant and less invasive source of mesenchymal stem cells than bone marrow.2 Human adipose tissue-derived stem cells (hASC) are an attractive cell source for generating other cells because these cells can secrete multiple growth factors and cytokines that exert beneficial effects on organ or injured tissue.3 hASC can be easily isolated from routine liposuction and reconstructive surgery waste materials. The accessibility, abundance, and immunosuppressive properties of hASC have attracted attention for uses in regenerative medicine.4 Despite this potential, however, hASC therapy in general is in its infancy. Problems, including heterogeneity of stem cells, uncertainty of correct differentiation into target tissue, and the risk of tumor formation, still remain to be addressed before application is justified in clinical settings.5 In addition to these difficulties, stem cell therapy can produce unexpected outcomes depending on the route of administration. Recently, we have observed pulmonary embolism and infarct among family members (index patient and his parents) who have taken multiple infusions of intravenous autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cells.

CASE REPORT

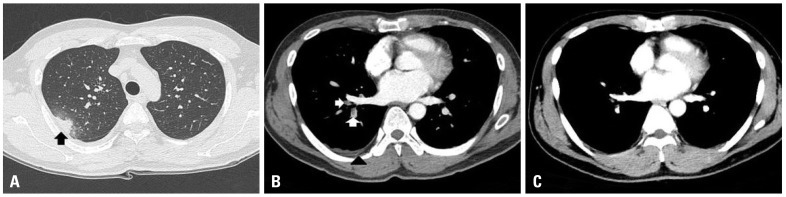

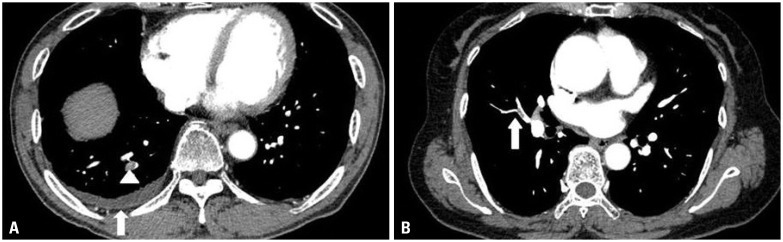

A forty-one year old man visited our hospital because of chest pain starting one month earlier. During the diagnostic work-up, chest CT revealed wedge-shaped consolidation at the subpleural area of the right upper lobe (Fig. 1A). In addition, multiple emboli were found in small pulmonary artery branches of both lungs with right pleural effusion (Fig. 1B). There was mild elevation of D-dimer (0.8 µg/mL, normal; 0-0.5 µg/mL) which suggested the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism and infarct. Full diagnostic work-up for hypercoagulability was done. Antinuclear antibody, anti-dsDNA and lupus anticoagulant were all negative. Levels of anti-cardiolipin antibody, homocysteine and anti-thrombin III and activity of protein C and S were within normal range. Factor V Leiden gene mutation was not detected. There was no evidence of deep vein thrombosis in his lower extremities by Doppler ultrasound. He was a non-smoker and did not have chronic illnesses. He did not take a medicine and had not recently taken airplane for a long period. We were puzzled about the cause of the multiple embolism and infarct. We checked his medical history more closely and he confessed to having taken autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cell therapy for cervical herniated intervertebral disc three times intravenously. The each stem cell therapy was at intervals of one month and the last treatment was finished one month before his visit. We considered the possibility of pulmonary embolism by intravenous infusion of hASC. The suspicion of IV stem cell therapy as the cause of pulmonary embolism became more solidified when we came to know that his parents had taken the same therapy for treatment of knee osteoarthritis five times. We invited them for diagnostic work up. They had no specific respiratory symptoms. His father was a current smoker (40 pack years) and his mother was a non smoker. Except for old age, they did not have risk factors for thromboembolism. His father's chest CT showed similar findings: there were multiple emboli at both pulmonary artery branches with right pleural effusion (Fig. 2A). In addition, pulmonary infarct was noted at the periphery of right lower lobe. Serum D-dimer was also elevated (1.0 µg/mL). As for his mother, we also confirmed multiple emboli in the pulmonary artery branches in both lungs (Fig. 2B) with mild elevation of serum D-dimer (1.1 µg/mL). They had no abnormal findings in the tests for hypercoagulability either. The index patient was first treated with enoxafarin, and then overlapped and switched to warfarin. Anti-coagulant therapy was stopped after a month because of the development of hematuria. His parents were observed without anti-coagulation therapy. Follow-up chest CT taken three month later showed disappearance of pleural effusion in index patient (Fig. 1C) and in his father. Pulmonary emboli were not detected in any of them.

Fig. 1.

Chest CT of patient. (A) Chest CT demonstrates wedge-shaped, peripheral consolidation at upper lobe of right lung (black arrow), which is consistent with pulmonary infarct. (B) Chest CT shows multiple filling defects (white arrows) at segmental pulmonary artery branches of right lung along with right pleural effusion (black arrow head). (C) Follow-up chest CT taken three month later showed disappearance of pleural effusion and pulmonary emboli.

Fig. 2.

Chest CT of his father (A) revealed multiple emboli at segmental pulmonary artery branch (white arrow head) and right pleural effusion (white arrow). Chest CT of his mother (B) showed linear emboli (white arrow) along the lumen of pulmonary artery branch of right lung.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have shown that hASC can be induced to express the cartilage-like gene and to synthesize cartilage matrix molecule.6,7 In animal studies, injection of ASC improved symptoms of osteoarthritis and decreased functional disability.8,9 However, as far as we are aware of, it is illegal in South Korea to inject stem cells into human body without special Institutional Review Board permission whether it is autologous or not. The local Korean bioengineering company responsible for this therapy which specializes in adult stem cells tried to avoid the legal issue by administering stem cells in foreign countries (China and Japan).10 The sampling, purification and collection of hASC are performed in Korean territory. The strategy may allow them to avoid the legal jurisdiction of Korean authorities. However, they cannot escape from ethical issue in that they tried stem cell therapy for the treatment of cervical herniated intervertebral disc for the index patient and knee osteoarthritis of his parents, which are totally unacceptable indications. It is not only unreasonable but also quite dangerous to inject stem cells intravenously. It has already been reported that IV infusion of stem cells can result in pulmonary embolism and even death in animal study.11,12 Takahashi, et al.11 tried intralesional, intrathecal or intravenous stem cell therapy for spinal cord injury in mice. In the IV group, no grafted cells were detected in the injury site. All of the mice showed pulmonary embolism and one-third of them died immediately after IV injection of stem cells. In other study, when hASC was injected into abdominal aorta, the blood microcirculation was interrupted and 25-40% of animals died of pulmonary embolism.12

It has been shown that tissue factor is highly expressed and localized on the cell surface of cultured ASC, and that tissue factor is a triggering factor in the coagulation pathway activated by infused ASC.13 It is, therefore, highly likely that injected hASC provoked coagulation pathway and resulted in multiple pulmonary embolism in our three cases.

To our best knowledge, this is the first case report of pulmonary embolism after IV stem cell therapy which occurred in all three recipients who are all family members. Intravenous injection of autologous hASC therapy can result in pulmonary embolism (and infarction too). However promising it may be, therefore, unauthorized administration of stem cells via intravenous route cannot be justified until scientifically proven otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This Research was supported by the Chung-Ang University Research Grants in 2013.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Robinton DA, Daley GQ. The promise of induced pluripotent stem cells in research and therapy. Nature. 2012;481:295–305. doi: 10.1038/nature10761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen JF, Sugawara A, Yamashita J, Ogura H, Sato S. Dedifferentiated fat cells: an alternative source of adult multipotent cells from the adipose tissues. Int J Oral Sci. 2011;3:117–124. doi: 10.4248/IJOS11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sensebé L, Bourin P. Mesenchymal stem cells for therapeutic purposes. Transplantation. 2009;87(9 Suppl):S49–S53. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a28635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parker AM, Katz AJ. Adipose-derived stem cells for the regeneration of damaged tissues. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2006;6:567–578. doi: 10.1517/14712598.6.6.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brignier AC, Gewirtz AM. Embryonic and adult stem cell therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 Suppl 2):S336–S344. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erickson GR, Gimble JM, Franklin DM, Rice HE, Awad H, Guilak F. Chondrogenic potential of adipose tissue-derived stromal cells in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290:763–769. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winter A, Breit S, Parsch D, Benz K, Steck E, Hauner H, et al. Cartilage-like gene expression in differentiated human stem cell spheroids: a comparison of bone marrow-derived and adipose tissue-derived stromal cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:418–429. doi: 10.1002/art.10767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black LL, Gaynor J, Adams C, Dhupa S, Sams AE, Taylor R, et al. Effect of intraarticular injection of autologous adipose-derived mesenchymal stem and regenerative cells on clinical signs of chronic osteoarthritis of the elbow joint in dogs. Vet Ther. 2008;9:192–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black LL, Gaynor J, Gahring D, Adams C, Aron D, Harman S, et al. Effect of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem and regenerative cells on lameness in dogs with chronic osteoarthritis of the coxofemoral joints: a randomized, double-blinded, multicenter, controlled trial. Vet Ther. 2007;8:272–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cyranoski D. Korean deaths spark inquiry. Nature. 2010;468:485. doi: 10.1038/468485a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi Y, Tsuji O, Kumagai G, Hara CM, Okano HJ, Miyawaki A, et al. Comparative study of methods for administering neural stem/progenitor cells to treat spinal cord injury in mice. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:727–739. doi: 10.3727/096368910X536554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furlani D, Ugurlucan M, Ong L, Bieback K, Pittermann E, Westien I, et al. Is the intravascular administration of mesenchymal stem cells safe? Mesenchymal stem cells and intravital microscopy. Microvasc Res. 2009;77:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tatsumi K, Ohashi K, Matsubara Y, Kohori A, Ohno T, Kakidachi H, et al. Tissue factor triggers procoagulation in transplanted mesenchymal stem cells leading to thromboembolism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;431:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]