Abstract

Background

Physical activity has been consistently associated with lower postmenopausal breast cancer risk, but its relationship with premenopausal breast cancer is unclear. We investigated whether physical activity is associated with reduced incidence of premenopausal breast cancer, and if so, what age period and intensity of activity are critical.

Methods

A total of 64,777 premenopausal women in the Nurses’ Health Study II reported, starting on the 1997 questionnaire, their leisure-time physical activity from age 12 to current age. Cox regression models were used to examine the relationship between physical activity categorized by age period (adolescence, adulthood, and lifetime) and intensity (strenuous, moderate, walking, and total) and risk of invasive premenopausal breast cancer.

Results

During 6 years of follow-up, 550 premenopausal women developed breast cancer. The strongest associations were for total leisure-time activity during participants’ lifetimes rather than for any one intensity or age period. Active women engaging in 39 or more metabolic equivalent hours per week (MET-h/wk) of total activity on average during their lifetimes, had a 23% lower risk of premenopausal breast cancer (relative risk =0.77; 95% confidence interval = 0.64 to 0.93) than women reporting less activity. That level of total activity is equivalent to 3.25 h/wk of running or 13 h/wk of walking. The age-adjusted incidence rates of breast cancer for the highest (≥ 54 MET-h/wk) and lowest (<21 MET-h/wk) total lifetime physical activity categories were 136 and 194 per 100 000 person-years, respectively. High quantities of physical activity during ages 12–22 years contributed most strongly to the association.

Conclusions

Leisure-time physical activity was associated with a reduced risk for premenopausal breast cancer in this cohort. Premenopausal women regularly engaging in high amounts of physical activity during both adolescence and adulthood may derive the most benefit.

A quarter of all breast cancer diagnoses occur among premenopausal women (1), but few modifiable risk factors have been identified. Breast cancers among young women are more likely to have a higher grade, increased proliferation rate, and higher vascular invasion and may be more difficult to treat than breast cancers among older women (2, 3). Moreover, risk factors such as body mass index (BMI) (4, 5), oral contraceptive use (6), and reproductive characteristics (7) vary by menopausal status, suggesting different etiologies for pre- and postmenopausal breast cancers. An expert panel of the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer research (8) and a recent systematic review (9) suggest that physical activity is associated with lower postmenopausal breast cancer incidence but that the relationship for premenopausal breast cancer is uncertain. Further unresolved questions include the role of physical activity at different age periods and intensity of activity on premenopausal breast cancer risk.

Physical activity has been hypothesized to reduce breast cancer risk through several mechanisms, including lowering the production or bioavailability of endogenous hormones such as estrogen, insulin, and insulin-like growth factor (IGF), which can act as mitogens (10, 11). Estrogen stimulates the growth and division of epithelial breast cells, which can potentially increase cancer risk by allowing for the propagation of genetic errors. Insulin and IGF may raise cancer risk by increasing cellular proliferation and survival (12). Moreover, it has been hypothesized that the mechanism by which physical activity acts varies over time. Exposures during adolescence may be particularly relevant for breast cancer development, because this period is characterized by increases in sex hormone levels and rapid proliferation of incompletely differentiated breast tissue. Among girls, strenuous activity is associated with later menarche and delayed establishment of regular menstrual cycles (13–16). Among adult women, exercise is related to decreased sex hormone levels, increased frequency of anovulation, and increased incidence of amenorrhea (17–19). Physical activity during both adolescence and adulthood may confer the greatest benefit for breast cancer risk by lowering lifetime levels of hormone risk factors (20). However, only three prospective studies (21–23), including one with only 12 breast cancer patients, have examined physical activity before adulthood and none have examined lifetime activity in detail.

In this study, we investigated whether physical activity is associated with reduced incidence of premenopausal breast cancer, and if so, what age period and intensity of exercise are most critical. In two earlier prospective investigations, we did not detect an association between premenopausal breast cancer and leisure-time physical activity during adolescence (22) or adulthood (24). Here, we used a more detailed measure of adolescent physical activity and investigated the role of lifetime (ages 12 year to current) physical activity. Based on proposed biologic mechanisms and some observational findings, we hypothesized that physical activity is associated with reduced risk of premenopausal breast cancer.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study Population

The Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) is an ongoing cohort study that began in 1989, when 116,608 female registered nurses (aged 25–42 years) completed a self-administered questionnaire about risk factors for cancer. Biennially, participants are sent a follow-up questionnaire to update information on lifestyle factors and to report newly diagnosed conditions; response rates are approximately 90%. Reports of death are confirmed by searches of the National Death Index (25, 26).

For this analysis, we followed women for 6 years, starting in 1997, when participants, who were then 33 to 51 years of age, reported their adolescent and adult physical activity. Women were excluded if they died before 1997, had a report of cancer (except for nonmelanoma skin cancer) before 1997, were diagnosed with breast cancer that was not invasive, did not report their physical activity during their youth, or were postmenopausal. After these exclusions, 64,777 eligible premenopausal women remained. This study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. Written informed consent was assumed upon completion and return of the questionnaire.

Assessment of Physical Activity

In 1997, participants were asked about their walking or leisure-time activity (i.e., outside of work) during five age periods: grades 7–8 (ages 12–13), grades 9–12 (ages 14–17), ages 18–22, ages 23–29, and ages 30–34. For each period, participants reported the average hours per week they engaged in each of three activity categories, with examples given for each: strenuous (eg, running, aerobics, swimming laps), moderate (eg, hiking, walking for exercise, casual cycling, and yard work), and walking to and from school or work. In 1997 and again in 2001, participants reported the average hours per week spent on the following walking or leisure-time activities in the previous year: jogging, running, bicycling (including stationary machine), racquet sports, swimming laps, walking or hiking outdoors, calisthenics or aerobics, and other aerobic activity.

Occupational activity was assessed in 1997 when participants were asked to best describe their work activity during ages 23–29 and 30–34; answer choices were: not employed, mostly sitting, mostly standing, mostly walking with little lifting, mostly walking with much lifting, and heavy manual labor. Similar questions have been used in other studies (27, 28). In this investigation, we chose, a priori, to primarily examine activity outside of work, because there was little variation in participants’ reported occupational levels (86% reported mostly walking with little or some amount of lifting).

All these physical activity questions are available online (29). When we evaluated the leisure-time physical activity measures, they had good reproducibility and validity. Recalled activity during the first three life periods had high 4-year reproducibility in a subgroup of 160 NHSII participants (average correlation r= .76 for strenuous, r=.70 for strenuous plus moderate, and r=.64 for total activity) (30). As for validity, our measure of physical activity in the previous year performed well when compared with previous week activity recalls (r=.79, 95% CI= 0.64 to 0.88) and separately, with four 7-day activity diaries (r=.62, 95% CI=0.44 to 0.75) in a subsample of NHSII participants (31). Moreover, in a validation study among 238 men, higher past-year vigorous activity, as self-reported on a similar activity assessment, was associated with lower resting pulse (r=−.45) (32). Furthermore, among 50 women aged 20 to 59, the physical activity score, as determined on a similar questionnaire, was correlated with maximal oxygen consumption (a measure of physical fitness) (r=.54) (33).

Estimation of Physical Activity by Intensity and Age

To classify intensity of leisure-time activity, each past-year activity was assigned a metabolic equivalent (MET) value (31) based on the categorizations by Ainsworth et al. (34). The MET value is the ratio of the metabolic rate of an activity divided by the resting metabolic rate and generally describes the effort required for that activity (34). For example, running (12 METs) requires 12 times the energy as sitting quietly. We defined jogging, running, bicycling (including stationary machine), racquet sports, and swimming laps as strenuous (≥ 7.0 METs). Calisthenics or aerobics and other aerobic activity were moderate (4.0–6.0 METs); walking was categorized separately, with METs assigned according to pace (average = 3 METs). The intensity categories were based on Center for Disease Control (CDC) designations (35) and are consistent with a recent 2007 consensus (36).

In these analyses, strenuous, moderate, and walking activities were expressed in hours per week and calculated by summing the hours per week of each activity. Total activity, expressed in MET-hours per week (MET h/wk), was computed by multiplying the hours per week of strenuous, moderate, and walking activities with their corresponding MET value and summing the values. To estimate activity levels for the five life periods, we assigned strenuous, moderate, and walking categories MET values of 7.0, 4.5, and 3.0, respectively.

To obtain mean leisure-time activity (for strenuous, moderate, walking, and total) during different age periods, we averaged activity levels for specific ages and across a woman’s lifetime. We used linear interpolation to calculate yearly adult activity between the last life period report for ages 30–34 and the past-year assessments. For example, in the case of a woman who was 45 in 1997, linear interpolation was used to estimate her activity for each age between 34 and 45, assuming that activity changed at the same rate. Mean lifetime physical activity was calculated by averaging activity from age 12 to the participant’s current age. For example, if the sum of a 45-year-old woman’s total activity from ages 12 to 45 (as weekly averages for each year) was 1320 MET h/wk, her lifetime average would be 38.8 MET h/wk (1320 MET/34). We similarly computed mean activity levels of women at ages 12–22 (referred to as “youth” for simplicity), 23–34, and greater than or equal to age 35.

For occupational activity, we assigned MET values based on the occupational activity categorizations of Ainsworth et al. (37): mostly sitting (1.5 METS), mostly standing (3.0 METS), mostly walking with little lifting (3.8 METS), mostly walking with much lifting (4.5 METS), and heavy manual labor (7.0 METS). We estimated work activity in MET h/wk by multiplying 40 h/wk (the average work week in the United States) by the activity’s corresponding MET value. Thus, if a respondent chose mostly sitting during ages 23–29, her estimated work activity would be 60 MET-hr/wk (1.5 METS × 40 hr/wk). Occupational activity during ages 23–34 was obtained by calculating a weighted average of activity levels from ages 23–29 and 30–34 with the weights being the number of years in each period. Leisure plus occupational activity, in MET h/wk, was the average of the two values. Individuals who reported not being employed were excluded from the occupation-related analyses.

Assessment of Incident Breast Cancer

Self-reported diagnoses of breast cancer on biennial NHSII questionnaires were confirmed by study physicians who, blinded to patient exposure status, reviewed participants’ medical records and pathology reports. Details about the diagnosis, including hormone-receptor status, were also recorded. We identified 739 premenopausal women with a breast cancer diagnosis between 1997 and 2003 who had physical activity data. We excluded all in situ cancers (n=159) and 30 unconfirmed breast cancer diagnoses, leaving 550 women with diagnoses of invasive premenopausal breast cancer during follow-up. There were too few invasive postmenopausal breast cancers (n=129) during the follow-up period to analyze separately.

Covariates

Age at menarche, height, childhood body shape, and menstrual length and pattern during ages 18–22 years were reported on the 1989 questionnaire. Birthweight was reported in 1991, and alcohol and fat intakes were obtained on the 1995 questionnaire. Information on other risk factors used in this investigation, including parity, age at first birth, history of benign breast disease, oral contraceptive use, menopausal status, use of multivitamins, smoking, and body weight were reported on the 1997 questionnaire and updated every 2 years on subsequent questionnaires. Television watching was reported in 1997. Information about family history of breast cancer in mother and/or sister was obtained in 1989 and 1997, and data on socioeconomic status was collected in 1999 and 2001.

Statistical Analysis

Each participant contributed person-time from the return date of her questionnaire in 1997 until menopause, a diagnosis of breast cancer or other cancer (except nonmelanoma skin cancer), death, or the end of follow-up on June 1, 2003, whichever came first, giving 335,681 person-years of follow-up. Person-time was assigned to the appropriate level of physical activity and covariate categories at the beginning of each 2-year questionnaire cycle.

Spearman rank correlation coefficients between physical activity categories and their associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were based on the arsin transformation approach (38). For breast cancer risk, Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the age-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted relative risks (RRs) and their 95% CIs. Age in months was the time scale. Physical activity exposures were divided into approximate quintiles and grouped into categories divisible by 3, the MET of average-paced walking. Relative risks represented the ratio of breast cancer incidence rates comparing each upper category of physical activity with the lowest group, adjusting for risk factors.

In multivariable analyses, we adjusted for several established risk factors for breast cancer: age (months), average childhood body shape [collapsed pictogram scale from 1 to ≥ 5, (39)], duration and recency of oral contraceptive use (never, past <4 y, past ≥ 4 y, current < 4 y, and current ≥ 4 y), history of benign breast disease (yes, no), mother or sister with breast cancer (yes, no), parity and age at first birth (afb) (nulliparous; parity 1–2, afb<25; parity 1–2, afb ≥ 30; parity ≥ 3, afb <25 parity ≥ 3, afb 25–29; parity ≥ 3, afb ≥ 30), current alcohol consumption (none, >0.0–1.4 g/day, 1.5–4.9 g/day, 5.0–9.9 g/day, ≥ 10 g/day), and height (inches). Adjustment for other possible confounders (smoking, smoking cessation, animal fat intake, birthweight, television watching, multivitamin use, and socioeconomic status) did not change the relative risk estimates and were omitted from our final model. We did not include BMI or age at menarche as core covariates because we considered them intermediates in the causal pathway between physical activity and breast cancer. However, these and other hypothesized intermediates were evaluated in additional models to examine potential mechanisms for the activity-breast cancer associations (discussed in Results). Tests for linear trend were performed by modeling the exposure as a continuous variable (there were no outliers). We examined effect modification by factors (BMI, oral contraceptive use, parity) that had biologic plausibility and for which we had sufficient numbers to conduct stratified analyses; tests of interaction were based on a Wald test of the interaction term. We observed no violation of proportional hazards by age. In ad-hoc analyses to further investigate which age periods were critical for the association with breast cancer risk, we examined whether adolescent and adult activity were statistically significantly different from each other by entering both in the same regression model as continuous terms and evaluating the whether the difference between their betas was statistically significant. For this, we used the test statistic (beta1–beta2)/standard error (beta1–beta2) and a standard normal table to evaluate the P value. All P values were two-sided. A P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. These analyses were performed using SAS version 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

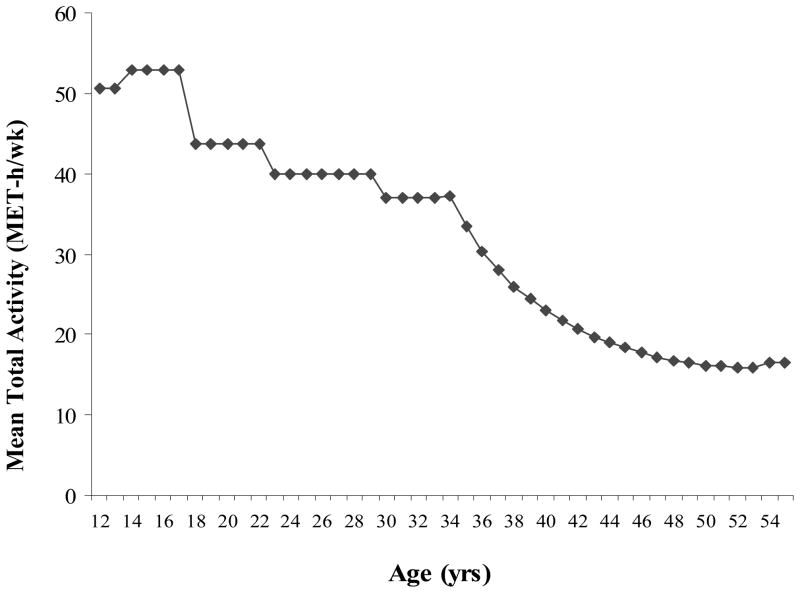

We first examined the pattern of total levels of leisure-time physical activity over time when participants were between the ages 12 and 55 (eldest in 2001). Women’s average total activity levels declined appreciably with age (Figure 1). At young ages, women engaged in mostly strenuous or moderate activities; for adults, walking was most common.

Figure 1.

Mean (diamonds) total leisure-time activity (MET h/wk) of women ages 12–55 (eldest in 2001). There are steps in the figure because activity data before age 35 were obtained for specific life periods.

Several established or possible risk factors for breast cancer were associated with leisure-time physical activity at the start of follow-up in 1997 (Table 1). After adjusting for age, physically active women were more likely to currently use oral contraceptives, to be nulliparous, to be taller, to consume greater than 10 grams of alcohol per day (about one glass of wine), to take multivitamins, and to be current smokers. They had lower BMI (childhood, at age 18, and current) and animal fat intakes. More active women also were less likely to have an early age at menarche (<12 years) and long (>40 days) menstrual cycles than less active women. The magnitude of these associations was modest.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 64,777 Women in 1997 According to Categories of Average Lifetime Total Activity, Nurses’ Health Study II*

| Characteristic | MET-h/wk (median)

|

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <21 (14.5) | 21–29.9 (25.5) | 30–38.9 (34.3) | 39–53.9 (45.4) | ≥ 54 (68.2) | ||

| No. of participants | 16015 | 12592 | 11187 | 12390 | 12593 | — |

| Age, y | 42.8 | 42.1 | 41.7 | 41.3 | 41.0 | <.001 |

| Mother or sister with breast cancer, % | 9.2 | 9.2 | 9.3 | 9.5 | 8.9 | .82 |

| History of benign breast disease, biopsy confirmed, % | 14.7 | 14.5 | 14.8 | 14.9 | 14.7 | .13 |

| Current oral contraceptive user, % | 9.0 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 9.9 | .004 |

| Nulliparous, % | 17.9 | 17.7 | 18.5 | 19.6 | 22.7 | <.001 |

| Parity† | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | .009 |

| Age at first birth, y† | 26.5 | 26.7 | 26.8 | 26.9 | 26.9 | <.001 |

| Height, inches | 64.7 | 64.9 | 64.9 | 65.0 | 65.1 | <.01 |

| Birthweight, ≥ 8.5 lbs, % | 11.9 | 12.0 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 12.2 | .07 |

| Overweight during ages 5 and 10, % | 6.7 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 5.6 | <.001 |

| BMI at age 18, kg/m2 | 21.5 | 21.3 | 21.2 | 21.1 | 21.0 | <.001 |

| Current BMI, kg/m2 | 26.7 | 26.0 | 25.6 | 25.5 | 25.2 | <.001 |

| Alcohol intake ≥ 10 g/day, %‡ | 6.7 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 10.3 | 11.1 | <.001 |

| Multivitamin use, % | 46.8 | 50.0 | 52.1 | 52.7 | 55.5 | <.001 |

| Animal fat, % energy from‡ | 17.9 | 17.2 | 16.9 | 16.5 | 16.1 | <.001 |

| Current smoker, % | 8.6 | 8.5 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 10.2 | <.001 |

| Age at menarche, < 12 y, % | 25.7 | 23.0 | 23.1 | 22.7 | 22.9 | .06 |

| Irregular menstrual cycles or no periods at age 18–22 y, % | 10.2 | 9.9 | 8.9 | 9.2 | 10.3 | .66 |

| length of menstrual cycle at ages 18–22, >40 days, % | 8.6 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 7.6 | 7.7 | <.001 |

| Television watching, h/wk | 8.6 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 8.3 | 8.6 | .50 |

All means and percentages refer to data in 1997, unless otherwise noted and are standardized to the age distribution of the study population. P values (two-sided) were obtained using test. Wald tests, from an age-adjusted linear regression with normalized total activity as the continuous outcome.

Among parous women only.

Refers to data collected in 1995.

We investigated the role of intensity of leisure-time physical activity by conducting separate analyses of average lifetime strenuous, moderate, walking, and total activities (Table 2). The strongest association was for total activity. Risk of breast cancer was lower for women reporting 54 or greater MET-h/wk of total activity than for those reporting less than 21 MET-h/wk (RR=0.77, 95% CI= 0.59 to 1.01; Ptrend=.04). The age-adjusted incidence rates of breast cancer for these highest (≥54 MET-h/wk) and lowest (<21 MET-h/wk) total activity categories were 136 and 194 per 100 000 person-years, respectively. Because the results (Table 2) suggested a threshold effect, we compared women with 39 or greater MET-h/wk of total activity (equivalent to 3.25 h/wk of running) versus less than 39 MET-h/wk. We found a similar association (RR=0.77, 95% CI = 0.64 to 0.93), suggesting a threshold effect. Results for strenuous, moderate, and walking activities were not statistically significant and were further attenuated when we mutually adjusted for each activity, suggesting that the association was not dependent on a single intensity but rather on total activity. The moderate correlations between the different intensities limited the ability to identify one as most important.

Table 2.

Relative Risk (RR) of Premenopausal Breast Cancer by Intensity of Lifetime Physical Activity, Nurses’ Health Study II 1997–2003*

| Type of activity | Person-years | No. of cancers | Age-adjusted RR | Multivariable adjusted RR† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strenuous | ||||

| <1.0 h/wk | 69517 | 129 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| 1.0–1.9 | 82780 | 149 | 1.03 | 1.01 (0.79 to 1.28) |

| 2.0–2.9 | 68541 | 109 | 0.98 | 0.94 (0.72 to 1.22) |

| 3.0–3.9 | 46098 | 65 | 0.89 | 0.86 (0.64 to 1.17) |

| ≥ 4.0 | 68746 | 98 | 0.96 | 0.90 (0.68 to 1.18) |

| Ptrend | .14 | |||

| Moderate | ||||

| <1.0 h/wk | 38066 | 70 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| 1.0–1.9 | 86284 | 159 | 1.07 | 1.06 (0.80 to 1.41) |

| 2.0–2.9 | 76046 | 133 | 1.04 | 1.01 (0.75 to 1.36) |

| 3.0–3.9 | 53755 | 81 | 0.92 | 0.91 (0.66 to 1.26) |

| ≥ 4.0 | 81530 | 107 | 0.82 | 0.81 (0.59 to 1.10) |

| Ptrend | .08 | |||

| Walking | ||||

| <0.5 h/wk | 63008 | 98 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| 0.5–0.9 | 67493 | 132 | 1.16 | 1.14 (0.88 to 1.49) |

| 1.0–1.4 | 59723 | 86 | 0.86 | 0.85 (0.63 to 1.14) |

| 1.5–2.4 | 74012 | 135 | 1.08 | 1.04 (0.80 to 1.36) |

| ≥ 2.5 | 71445 | 99 | 0.83 | 0.79 (0.59 to 1.05) |

| Ptrend | .09 | |||

| Total activity | ||||

| <21.0 MET-h/wk | 81563 | 158 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| 21.0–29.9 | 65264 | 121 | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.77 to 1.25) |

| 30.0–38.9 | 58299 | 97 | 0.95 | 0.93 (0.72 to 1.20) |

| 39.0–53.9 | 64947 | 85 | 0.76 | 0.74 (0.56 to 0.97) |

| ≥ 54.0 | 65609 | 89 | 0.83 | 0.77 (0.59 to 1.01) |

| Ptrend | .04 | |||

RR=relative risk; CI = confidence interval; MET = metabolic equivalents; AFB = age at first birth.

Adjusted for the following covariates: age (months), average childhood body shape (collapsed pictogram scale from 1 to ≥ 5), duration and recency of oral contraceptive use (never, past <4 y, past ≥ 4 y, current < 4 y, and current ≥ 4 y), history of benign breast disease (yes, no), mother or sister with breast cancer (yes, no), parity and age at first birth [afb] (nulliparous; parity 1–2, afb<25; parity 1–2, afb ≥ 30; parity ≥ 3, afb <25 parity ≥ 3, afb 25–29; parity ≥ 3, afb ≥ 30), current alcohol consumption (none, >0.0–1.4 g/day, 1.5–4.9 g/day, 5.0–9.9 g/day, ≥ 10 g/day), and height (inches). Ptrend values (two-sided) were computed using the Wald test statistic.

To evaluate the role of leisure-time physical activity during specific ages of life, we examined total activity during three different life periods (Table 3). Activity during ages 12–22 had the strongest association. Higher total activity during that period was statistically significantly associated with a 25% lower breast cancer risk (for ≥ 72 vs <21 MET-h/wk, RR=0.75, 95% CI= 0.57 to 0.99; Ptrend = .05). The RRs were attenuated after mutually adjusting for activity before ages 23 years and at age 23 or greater (data not shown; between 12–22 and ≥23 age periods, r = 0.55, 95% CI= 0.56 to 0.57). The associations with activity during ages 12–17 years were similarly inverse (for ≥ 78 vs <21 MET-h/wk, RR=0.76, 95% CI= 0.58 to 0.99; Ptrend=.09; data not shown). We observed a suggestion of lower breast cancer risk with higher total activity during ages 23–34 (P trend=.06), but no association with reduced risk was apparent after age 35.

Table 3.

Relative Risk (RR) of Premenopausal Breast Cancer by Age Periods of Total Physical Activity, Nurses’ Health Study II 1997–2003*

| Age period | Person-years | No. of cancers | Age-adjusted RR | Multivariable adjusted RR* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages 12–22 years | ||||

| <21 MET-h/wk | 63582 | 128 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| 21.0–35.9 | 76770 | 136 | 0.95 | 0.94 (0.74 to 1.21) |

| 36.0–47.9 | 55607 | 86 | 0.85 | 0.82 (0.62 to 1.09) |

| 48.0–71.9 | 73251 | 112 | 0.85 | 0.82 (0.63 to 1.06) |

| ≥ 72.0 | 66471 | 88 | 0.76 | 0.75 (0.57 to 0.99) |

| Ptrend | .05 | |||

| For 21 MET h/wk increase† | −6% | |||

| Ages 23–34 years | ||||

| <15 MET-h/wk | 58559 | 91 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| 15.0–26.9 | 75723 | 155 | 1.38 | 1.38 (1.06 to 1.80) |

| 27.0–38.9 | 62353 | 102 | 1.13 | 1.12 (0.84 to 1.49) |

| 39.0–56.9 | 70410 | 110 | 1.08 | 1.04 (0.78 to 1.39) |

| ≥ 57.0 | 68636 | 92 | 0.93 | 0.88 (0.65 to 1.19) |

| Ptrend | .06 | |||

| For 21 MET h/wk increase† | −6% | |||

| Ages ≥ 35 years | ||||

| <9.0 MET-h/wk | 75004 | 117 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| 9.0–14.9 | 61015 | 115 | 1.15 | 1.19 (0.92 to 1.55) |

| 5.0–20.9 | 53001 | 90 | 1.02 | 1.02 (0.77 to 1.35) |

| 21.0–32.9 | 71402 | 99 | 0.81 | 0.80 (0.61 to 1.05) |

| ≥ 33.0 | 71943 | 128 | 1.05 | 1.00 (0.77 to 1.30) |

| Ptrend | .27 | |||

| For 21 MET h/wk increase† | −4% | |||

Adjusted for covariates listed in asterisk of footnote in Table 2. Ptrend values (two-sided) were computed using the Wald test statistic.

Percent change in RR for a 21 MET h/wk increase in total physical activity during the specific age period, from regression models with activity as a continuous term. For total activity averaged across the lifetime (ages 12 to present), a 21 MET-h/wk increase in activity was statistically significantly associated with a −9% risk (Ptrend=0.04).

Because activity declined with age, we modeled activity during the three age periods as continuous terms and calculated the relative risks for the same 21 MET-h/wk increment of total activity to be able to make direct comparisons between relative risks. The estimates for the different age periods were similar (−4% to −6%, Table 3) and not independently statistically significant. A 21 MET-h/wk increase of lifetime activity was statistically significantly associated with −9% risk.

We next categorized activity for 12–22 years (youth) and for 23 years and older (adulthood) into tertiles and cross-classified them to examine whether a specific pattern of activity was related to breast cancer risk (Table 4). The RR for the high during youth and low during adulthood (high-low) activity pattern (RR=0.63, 95% CI =0.35 to 1.11) was similar to that of the high-high activity pattern (RR = 0.70, 95% CI =0.53 to 0.93), suggesting that high levels of leisure-time physical activity during ages 12–22 were important, no matter the activity level during later years. However, most women were either inactive (low–low) or active (high–high) during both youth and adulthood, limiting our ability to examine specific age periods. Moreover, the associations with risk for activity during youth and adulthood were not statistically significantly different from each other when we entered each type of activity in the same regression model as continuous terms and evaluated the statistical significance of the difference between their betas.

Table 4.

Relative Risk (RR) of Premenopausal Breast Cancer by Patterns of Total Physical Activity During Youth (12–22 years) and Adulthood ( ≥ 23 years), Nurses’ Health Study II 1997–2003*

| Activity by age group | Person-years | No. of cancer | Multivariable adjusted RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low youth/low adulthood | 59947 | 118 | 1.00 (referent) |

| Low youth/high adulthood | 13945 | 22 | 0.83 (0.53 to 1.32) |

| High youth/low adulthood | 11874 | 13 | 0.63 (0.35 to 1.11) |

| High youth/high adulthood | 69462 | 89 | 0.70 (0.53 to 0.93) |

Multivariable relative risks are adjusted for core covariates listed in the asterisk of Table 2 footnote. The “low youth” category consisted of women in the bottom tertile of total activity (average of < 8 MET h-wk) during ages 12–22, whereas “high youth” represented those in the top tertile of total activity (average of >43 MET h-wk) during that age. The “low adulthood” category consisted of women in the top tertile of total activity (average of < 13 MET h-wk) from ages 23 years to present, whereas “high adulthood” represented women in the top tertile of total activity (> 26 MET h-wk) during that age. Not included in this table are 308 breast cancer patients and 180,454 person-years of women in the other cross-classifications of low, medium, and high categories of activity during youth and adulthood.

CI = confidence interval.

Because error in self-reporting can bias results, we corrected for measurement error by regression calibration (40, 41) using past-year adult activity from an earlier validation study (31). With the correction, we observed a 39% lower breast cancer risk for total lifetime physical activity comparing the most to the least active women, suggesting that our original estimate of a 23% lower risk was an underestimate of reduced risk.

We also evaluated the relationship between total lifetime physical activity and breast cancer risk by hormone receptor status. We observed a non–statistically significant inverse association for both estrogen receptor (ER)-positive (RR=0.76, 95% CI = 0.54 to 1.06; P trend=.15, for 363 patients) and ER-negative (RR=0.89, 95% CI= 0.48 to 1.63; Ptrend=.21, for 103 patients) breast cancers for the highest versus lowest categories of activity. Moreover, there were similar, non–statistically significant, inverse associations for breast cancers with concordant ER and progesterone receptor (PR) status (comparing the most versus least active women: for ER+/PR+, RR= 0.80, 95% CI= 0.56 to 1.15, and for ER−/PR−, RR= 0.86, 95% CI = 0.46 to 1.61). There were too few patients to examine discordant receptor status (e.g., ER−/PR+ or ER+/PR−).

Physical activity has been hypothesized to influence breast cancer risk by changing menstrual characteristics or BMI. Thus, we assessed the association between total lifetime activity and breast cancer risk after adjusting for age at menarche, regularity and length of menstrual cycle during youth and adulthood, and BMI (at age 18, current, and cumulatively updated). Relative risks were not appreciably different.

Lastly, we examined whether the relationship between total lifetime activity and breast cancer risk varied according to BMI, parity, or oral contraceptive use (Table 5, stratified analyses). Among women with a BMI of <25.0 kg/m2 in 1997, the most active women had a 32% lower risk compared with the least active women (RR=0.68, 95% CI= 0.48 to 0.98; Ptrend= .02). However, among overweight women (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2), activity was not statistically significantly associated with breast cancer risk (RR=0.85, 95% CI= 0.56 to 1.30; Ptrend= .60). In addition, we observed a statistically significant inverse activity-breast cancer risk association among parous women (most vs least active; RR=0.72, 95% CI = 0.53 to 0.98; Ptrend= .02) but not among nulliparous women (RR=1.08; Ptrend=.68). However, formal tests for interaction with current BMI (P= .10) and parity (P=.45) were not statistically significant. Moreover, there were no substantial differences by subgroups of BMI at age 18 (<20.5 kg/m2, ≥20.5 kg/m2, approximate median) or by oral contraceptive use (never, past, present use) in stratified analyses.

Table 5.

Relative Risks (RR) of Breast Cancer by Total Lifetime Activity, Stratified by Adult BMI and Parity, Nurses’ Health Study II 1997–2003*

| Activity, Met-h/wk | BMI <25 kg/m2 | BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 | Nulliparous | Parous | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| No. of cancers | RR (95% CI) | No. of cancers | RR (95% CI) | No. of cancers | RR (95% CI) | No. of cancers | RR (95% CI) | |

| < 21.0 | 86 | 1.00 (referent) | 72 | 1.00 (referent) | 29 | 1.00 (referent) | 128 | 1.00 (referent) |

| 21.0–29.9 | 66 | 0.88 (0.63 to 1.22) | 55 | 1.14 (0.80 to 1.63) | 19 | 0.79 (0.43 to 1.45) | 99 | 1.01 (0.77 to 1.32) |

| 30.0–38.9 | 62 | 0.95 (0.68 to 1.32) | 35 | 0.92 (0.61 to 1.38) | 20 | 1.09 (0.60 to 1.97) | 76 | 0.91 (0.68 to 1.21) |

| 39.0–53.9 | 52 | 0.72 (0.50 to 1.02) | 33 | 0.76 (0.49 to 1.16) | 19 | 0.84 (0.45 to 1.55) | 65 | 0.72 (0.53 to 0.97) |

| ≥ 54.0 | 53 | 0.68 (0.48 to 0.98) | 35 | 0.85 (0.56 to 1.30) | 26 | 1.08 (0.61 to 1.90) | 63 | 0.72 (0.53 to 0.98) |

| Ptrend | .02 | .60 | .68 | .02 | ||||

Adjusted for covariates listed in asterisk of footnote in Table 2. Current body mass index (BMI), as reported at 1997. CI = confidence interval. Ptrend values (two-sided) were calculated using the Wald test statistic.

There was little variation in work-related activity, with 86% of participants reporting mostly walking. The association of occupational activity during ages 23–34 years with breast cancer risk was non–statistically significantly inverse (for >171 MET-h/wk vs <114, RR= 0.83, 95% CI = 0.63 to 1.09; Ptrend= .42). The RR for leisure plus occupational activity during ages 23–34 years was 0.80 (for ≥ 216 MET-h/wk vs <147, 95% CI =0.61 to 1.04, Ptrend=.07). The correlation between occupational and total leisure-time activity during ages 23–34 years was low (r= .10, 95% CI = 0.10 to 0.11).

DISCUSSION

In this large prospective study, total activity was most strongly associated with lower risk of premenopausal breast cancer. Women who had engaged in at least 39 MET-h/wk of total activity on average from ages 12 years onward had a 23% lower risk of premenopausal breast cancer than the least active women. This activity level translates to about 3.25 h/wk of running or 13 h/wk of walking. High quantities of total activity during youth (12–22 years) appeared to contribute most to this benefit.

Epidemiologic results for the association of physical activity with premenopausal breast cancer risk have been inconsistent (8, 9)). Direct comparisons between investigations are particularly challenging due to the diversity in physical activity assessments, types of activity (e.g., leisure-time, occupational, household, total), units of activity, and the various study populations examined (42). For adolescent or lifetime leisure-time activity, there have been at least three prospective studies (21–23) and 15 case–control studies (20, 43–56) examining premenopausal breast risk. Wyshak (21) observed a very strong association between physical activity and reduced risk for breast cancer (RR=0.16, 95% CI= −0.04 to −0.64) in a prospective analysis comparing US college athletes versus nonathletes, but results were unstable, based on 12 patients. In a Swedish cohort, Margolis (23) did not detect a relationship for physical activity at age 14 or for consistently high activity levels of at ages 14, 30, and enrollment and premenopausal breast cancer risk. In an earlier NHSII analysis, we did not detect statistically significant associations between strenuous activity during high school or ages 18–22 and risk of premenopausal breast cancer (22); however, the two-question activity measure used for the analysis was probably not sufficiently detailed. Among case–control studies reporting on premenopausal breast cancer, six observed statistically significant associations (20, 43–48), ranging from moderate to strong decreased relative risks, and one (49) reported borderline, non–statistically significant inverse associations. Our study is consistent with these findings. Other case–control studies (50–56) have not found statistically significant associations.

For adult leisure-time activity, previously conducted cohort studies (23, 24, 27, 57–63) have not observed statistically significant associations with premenopausal breast cancer risk, consistent with our current study and an earlier NHSII analysis (24). This finding may be due, in part, to declining levels of physical activity after age 35; for example, few participants in our study reported very vigorous activities such as running. Few studies have examined associations between occupational physical activity and breast cancer risk. Among four cohort studies, two observed statistically significantly decreased risks (27, 64) with occupational activity, whereas two reported no statistically significant associations (63, 65). Among six case–control studies (47, 49, 52, 66–68), no statistically significant associations with occupational activity were reported. Studies have varied in the quality and completeness of their assessments of physical activity, and in some investigations, sample sizes have been small.

Our study adds to the current literature by being, to our knowledge, the first prospective study to collect data for a broad range of etiologically relevant ages (in this study, from ages, 12 to a maximum of 55) and to prospectively examine the role of activity throughout life. Further strengths of this investigation include its relatively large number of premenopausal invasive breast cancers and the medical confirmation of cancer diagnoses. In addition, the age- and multivariable-adjusted relative risks were similar, suggesting no major sources of confounding.

This study also has some limitations. First, we relied on self-reported activity, which will inevitably be imperfect. In our previous investigations, these physical activity questions had good reproducibility (30) and validity as compared with 7-day activity diaries in a subgroup of NHSII participants (31). Moreover, self-reported physical activity using a similar questionnaire was well correlated with lowered resting pulse in men (32) and maximal oxygen consumption in women (33). Second, adult activity between questionnaire cycles was linearly interpolated. Although errors due to reporting and estimation of activity levels are inevitable, when we corrected for such errors in the analysis, we observed a stronger risk reduction (39%), indicating that our original estimate may have underestimated the association. Third, physical activity was correlated across different ages and intensities, as has been seen in other studies (69, 70); this limited the ability to statistically identify one age period and intensity with the strongest association.

Our results are applicable to premenopausal white women. Although participants were registered nurses at the initiation of the study, previous exposure-disease relationships in this cohort, including those for breast cancer, have been confirmed in other populations, suggesting that our findings are generalizable on a population level. While this study focused primarily on leisure-time activity, we did not observe much variation in physical activity at work (most reported walking) or a statistically significant association between occupational physical activity with breast cancer risk. Despite homogeneity in occupation levels, there was sufficient variation in leisure-time activity to examine associations with breast cancer risk.

Physical activity has been hypothesized to lower breast cancer incidence through several hormone-related mechanisms (71). Estrogen is strongly implicated in breast cancer etiology (72, 73). Physical activity can delay menarche or change menstrual cycle characteristics (71, 74), and, thus, alter women’s lifetime exposure to the mitogenic effects of sex hormones (16). We observed modest changes in menstrual characteristics with increasing activity levels. Furthermore, among NHSII women, physical activity during adulthood has been inversely associated with plasma concentrations of luteal-phase estrodiol, free estradiol, and estrogen (75). Second, physical activity is known to lower insulin concentrations (76). Insulin can increase hepatic production of IGF (12, 77) and may raise levels of bioactive IGF and estrogen by lowering hepatic secretion of their respective binding proteins. IGF has been associated with increased premenopausal breast cancer risk (78), but results are conflicting (79, 80). We observed suggestive inverse associations for both ER+ and ER− breast cancers, as had a previous study (81), suggesting that both ovarian and nonovarian hormonal mechanisms could be involved.

Although most studies suggest that physical activity during adulthood is associated with at least a 20% reduced risk of postmenopausal breast cancer (9, 82), this and other investigations indicate that women need to regularly engage in physical activity starting at a young age to achieve a comparable benefit for premenopausal breast cancer. Unresolved questions for future investigations include whether higher physical activity during adolescence is associated with reduced risk of postmenopausal breast cancer, the role of physical activity at earlier ages such as during childhood, the role of occupational activity, and the mechanisms underlying a potential association with breast cancer risk. Only a handful of case–control studies have reported results in African-American (46, 48) and Hispanic (48, 83) populations, and it is unclear whether the physical activity-breast cancer association differs by ethnicity.

In conclusion, these results suggest that consistent physical activity during a woman’s lifetime is associated with decreased breast cancer risk. Unlike many risk factors for breast cancer, physical activity is an exposure that can be modified. This association, if found to be causal, has public health implications for prevention. Moreover, physical activity at any age promotes health in many ways (84, 85), and even walking has several well-documented benefits (86). Although the underlying mechanisms require further study, this research supports the benefits of regular exercise during all ages among women.

Acknowledgments

Funding

National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (grant CA50385 and R25 CA98566 to S.S.M.). G.A.C was supported by an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professorship.

The funding agency did not have a role in the design, conduct, analysis, decision to report, or writing of the study.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts and Figures 2005–2006. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris J, Lippman ME, Morrow M, Osborne CKE. Diseases of the Breast. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klauber-Demore N. Tumor biology of breast cancer in young women. Breast Dis. 2005;23:9–15. doi: 10.3233/bd-2006-23103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Brandt PA, Spiegelman D, Yaun SS, Adami HO, Beeson L, Folsom AR, et al. Pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies on height, weight, and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(6):514–27. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.6.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedenreich CM. Review of anthropometric factors and breast cancer risk. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2001;10(1):15–32. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200102000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Lancet. 1996;347(9017):1713–27. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90806-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedenreich CM. Physical activity and breast cancer risk: the effect of menopausal status. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2004;32(4):180–4. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200410000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington, D.C: AICR; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monninkhof EM, Elias SG, Vlems FA, van der Tweel I, Schuit AJ, Voskuil DW, et al. Physical activity and breast cancer: a systematic review. Epidemiology. 2007;18(1):137–57. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000251167.75581.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedenreich CM, Orenstein MR. Physical activity and cancer prevention: etiologic evidence and biological mechanisms. J Nutr. 2002;132(11 Suppl):3456S–3464S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.11.3456S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman-Goetz L. Physical activity and cancer prevention: animal-tumor models. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(11):1828–33. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000093621.09328.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giovannucci E. Nutrition, insulin, insulin-like growth factors and cancer. Horm Metab Res. 2003;35(11–12):694–704. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malina RM, Spirduso WW, Tate C, Baylor AM. Age at menarche and selected menstrual characteristics in athletes at different competitive levels and in different sports. Med Sci Sports. 1978;10(3):218–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frisch RE, Wyshak G, Vincent L. Delayed menarche and amenorrhea in ballet dancers. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(1):17–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198007033030105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frisch RE, Gotz-Welbergen AV, McArthur JW, Albright T, Witschi J, Bullen B, et al. Delayed menarche and amenorrhea of college athletes in relation to age of onset of training. Jama. 1981;246(14):1559–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernstein L, Ross RK, Lobo RA, Hanisch R, Krailo MD, Henderson BE. The effects of moderate physical activity on menstrual cycle patterns in adolescence: implications for breast cancer prevention. Br J Cancer. 1987;55(6):681–5. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1987.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Consitt LA, Copeland JL, Tremblay MS. Endogenous anabolic hormone responses to endurance versus resistance exercise and training in women. Sports Med. 2002;32(1):1–22. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sternfeld B, Jacobs MK, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Gold EB, Sowers M. Physical activity and menstrual cycle characteristics in two prospective cohorts. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(5):402–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loucks AB, Horvath SM. Athletic amenorrhea: a review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1985;17(1):56–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernstein L, Henderson BE, Hanisch R, Sullivan-Halley J, Ross RK. Physical exercise and reduced risk of breast cancer in young women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86(18):1403–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.18.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wyshak G, Frisch RE. Breast cancer among former college athletes compared to non-athletes: a 15-year follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2000;82(3):726–30. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rockhill B, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Physical activity and breast cancer risk in a cohort of young women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(15):1155–60. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.15.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margolis KL, Mucci L, Braaten T, Kumle M, Trolle Lagerros Y, Adami HO, et al. Physical activity in different periods of life and the risk of breast cancer: the Norwegian-Swedish Women’s Lifestyle and Health cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(1):27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colditz GA, Feskanich D, Chen WY, Hunter DJ, Willett WC. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer in premenopausal women. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(5):847–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Dysert DC, Lipnick R, Rosner B, et al. Test of the National Death Index. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119(5):837–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rich-Edwards JW, Corsano KA, Stampfer MJ. Test of the National Death Index and Equifax Nationwide Death Search. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140(11):1016–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thune I, Brenn T, Lund E, Gaard M. Physical activity and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(18):1269–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705013361801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartman TJ, Albanes D, Rautalahti M, Tangrea JA, Virtamo J, Stolzenberg R, et al. Physical activity and prostate cancer in the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene (ATBC) Cancer Prevention Study (Finland) Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9(1):11–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1008889001519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nurses’ Health Study Website: Questionnaires. Channing Laboratory, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School; Boston, MA: 2007. ( http://www.channing.harvard.edu/nhs/questionnaires/index.shtml) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baer HJ, Schnitt SJ, Connolly JL, Byrne C, Willett WC, Rosner B, et al. Early life factors and incidence of proliferative benign breast disease. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(12):2889–97. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Corsano KA, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23(5):991–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.5.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chasan-Taber S, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Spiegelman D, Colditz GA, Giovannucci E, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire for male health professionals. Epidemiology. 1996;7(1):81–6. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199601000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobs DR, Jr, Ainsworth BE, Hartman TJ, Leon AS. A simultaneous evaluation of 10 commonly used physical activity questionnaires. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25(1):81–91. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, Jacobs DR, Jr, Montoye HJ, Sallis JF, et al. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25(1):71–80. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, Powell KE, Blair SN, Franklin BA, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1423–34. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616b27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, Haskell WL, Macera CA, Bouchard C, et al. Physical activity and public health. A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. Jama. 1995;273(5):402–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9 Suppl):S498–504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosner B, Glynn RJ. Interval estimation for rank correlation coefficients based on the probit transformation with extension to measurement error correction of correlated ranked data. Stat Med. 2007;26(3):633–46. doi: 10.1002/sim.2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baer HJ, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Michels KB, Rich-Edwards JW, Hunter DJ, et al. Body fatness during childhood and adolescence and incidence of breast cancer in premenopausal women: a prospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7(3):R314–25. doi: 10.1186/bcr998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosner B, Willett WC, Spiegelman D. Correction of logistic regression relative risk estimates and confidence intervals for systematic within-person measurement error. Stat Med. 1989;8(9):1051–69. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080905. discussion 1071–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spiegelman D, McDermott A, Rosner B. Regression calibration method for correcting measurement-error bias in nutritional epidemiology. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(4 Suppl):1179S–1186S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.4.1179S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ainsworth BE, Sternfeld B, Slattery ML, Daguise V, Zahm SH. Physical activity and breast cancer: evaluation of physical activity assessment methods. Cancer. 1998;83(3 Suppl):611–20. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980801)83:3+<611::aid-cncr3>3.3.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang D, Bernstein L, Wu AH. Physical activity and breast cancer risk among Asian-American women in Los Angeles: a case-control study. Cancer. 2003;97(10):2565–75. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matthews CE, Shu XO, Jin F, Dai Q, Hebert JR, Ruan ZX, et al. Lifetime physical activity and breast cancer risk in the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(7):994–1001. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verloop J, Rookus MA, van der Kooy K, van Leeuwen FE. Physical activity and breast cancer risk in women aged 20–54 years. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(2):128–35. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adams-Campbell LL, Rosenberg L, Rao RS, Palmer JR. Strenuous physical activity and breast cancer risk in African-American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2001;93(7–8):267–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorn J, Vena J, Brasure J, Freudenheim J, Graham S. Lifetime physical activity and breast cancer risk in pre- and postmenopausal women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(2):278–85. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000048835.59454.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.John EM, Horn-Ross PL, Koo J. Lifetime physical activity and breast cancer risk in a multiethnic population: the San Francisco Bay area breast cancer study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(11 Pt 1):1143–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steindorf K, Schmidt M, Kropp S, Chang-Claude J. Case-control study of physical activity and breast cancer risk among premenopausal women in Germany. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):121–30. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taioli E, Barone J, Wynder EL. A case-control study on breast cancer and body mass. The American Health Foundation--Division of Epidemiology. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A(5):723–8. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00046-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gammon MD, Schoenberg JB, Britton JA, Kelsey JL, Coates RJ, Brogan D, et al. Recreational physical activity and breast cancer risk among women under age 45 years. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(3):273–80. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Friedenreich CM, Bryant HE, Courneya KS. Case-control study of lifetime physical activity and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(4):336–47. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.4.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen CL, White E, Malone KE, Daling JR. Leisure-time physical activity in relation to breast cancer among young women (Washington, United States) Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8(1):77–84. doi: 10.1023/a:1018439306604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sprague BL, Trentham-Dietz A, Newcomb PA, Titus-Ernstoff L, Hampton JM, Egan KM. Lifetime recreational and occupational physical activity and risk of in situ and invasive breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(2):236–43. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu YH, Nagata C, Shimizu H, Kaneda N, Kashiki Y. Association of body mass index, physical activity, and reproductive histories with breast cancer: a case-control study in Gifu, Japan. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1997;43(1):65–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1005745824388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Slattery ML, Edwards S, Murtaugh MA, Sweeney C, Herrick J, Byers T, et al. Physical activity and breast cancer risk among women in the southwestern United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(5):342–53. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rockhill B, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA. A prospective study of recreational physical activity and breast cancer risk. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(19):2290–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.19.2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Breslow RA, Ballard-Barbash R, Munoz K, Graubard BI. Long-term recreational physical activity and breast cancer in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I epidemiologic follow-up study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10(7):805–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luoto R, Latikka P, Pukkala E, Hakulinen T, Vihko V. The effect of physical activity on breast cancer risk: a cohort study of 30,548 women. Eur J Epidemiol. 2000;16(10):973–80. doi: 10.1023/a:1010847311422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Albanes D, Blair A, Taylor PR. Physical activity and risk of cancer in the NHANES I population. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(6):744–50. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.6.744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee SY, Kim MT, Kim SW, Song MS, Yoon SJ. Effect of lifetime lactation on breast cancer risk: a Korean women’s cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2003;105(3):390–3. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Lee IM. Physical activity and breast cancer risk in the College Alumni Health Study (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9(4):433–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1008827903302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lahmann PH, Friedenreich C, Schuit AJ, Salvini S, Allen NE, Key TJ, et al. Physical activity and breast cancer risk: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(1):36–42. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rintala PE, Pukkala E, Paakkulainen HT, Vihko VJ. Self-experienced physical workload and risk of breast cancer. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2002;28(3):158–62. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moradi T, Adami HO, Bergstrom R, Gridley G, Wolk A, Gerhardsson M, et al. Occupational physical activity and risk for breast cancer in a nationwide cohort study in Sweden. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10(5):423–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1008922205665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coogan PF, Newcomb PA, Clapp RW, Trentham-Dietz A, Baron JA, Longnecker MP. Physical activity in usual occupation and risk of breast cancer (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8(4):626–31. doi: 10.1023/a:1018402615206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kruk J, Aboul-Enein HY. Occupational physical activity and the risk of breast cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27(3):187–92. doi: 10.1016/s0361-090x(03)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ueji M, Ueno E, Osei-Hyiaman D, Takahashi H, Kano K. Physical activity and the risk of breast cancer: a case-control study of Japanese women. J Epidemiol. 1998;8(2):116–22. doi: 10.2188/jea.8.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bernstein L, Patel AV, Ursin G, Sullivan-Halley J, Press MF, Deapen D, et al. Lifetime recreational exercise activity and breast cancer risk among black women and white women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(22):1671–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alfano CM, Klesges RC, Murray DM, Beech BM, McClanahan BS. History of sport participation in relation to obesity and related health behaviors in women. Prev Med. 2002;34(1):82–9. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Westerlind KC. Physical activity and cancer prevention--mechanisms. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(11):1834–40. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000093619.37805.B7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eliassen AH, Missmer SA, Tworoger SS, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Dowsett M, et al. Endogenous steroid hormone concentrations and risk of breast cancer among premenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(19):1406–15. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pike MC, Spicer DV, Dahmoush L, Press MF. Estrogens, progestogens, normal breast cell proliferation, and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15(1):17–35. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hoffman-Goetz L, Apter D, Demark-Wahnefried W, Goran MI, McTiernan A, Reichman ME. Possible mechanisms mediating an association between physical activity and breast cancer. Cancer. 1998;83(3 Suppl):621–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980801)83:3+<621::aid-cncr4>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tworoger SS, Missmer SA, Eliassen AH, Barbieri RL, Dowsett M, Hankinson SE. Physical activity and inactivity in relation to sex hormone, prolactin, and insulin-like growth factor concentrations in premenopausal women - exercise and premenopausal hormones. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(7):743–52. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schulze MB, Hu FB. Primary prevention of diabetes: what can be done and how much can be prevented? Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:445–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kaaks R. Nutrition, insulin, IGF-1 metabolism and cancer risk: a summary of epidemiological evidence. Novartis Found Symp. 2004;262:247–60. discussion 260–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Michaud DS, Deroo B, et al. Circulating concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-I and risk of breast cancer. Lancet. 1998;351(9113):1393–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10384-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hankinson SE, Schernhammer ES. Insulin-like growth factor and breast cancer risk: evidence from observational studies. Breast Dis. 2003;17:27–40. doi: 10.3233/bd-2003-17104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rinaldi S, Peeters PH, Berrino F, Dossus L, Biessy C, Olsen A, et al. IGF-I, IGFBP-3 and breast cancer risk in women: The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13(2):593–605. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Adams SA, Matthews CE, Hebert JR, Moore CG, Cunningham JE, Shu XO, et al. Association of physical activity with hormone receptor status: the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(6):1170–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vanio H, Bianchini F. Weight control and Physical activity. Vol. 6. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. IARC handbooks of cancer prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gilliland FD, Li YF, Baumgartner K, Crumley D, Samet JM. Physical activity and breast cancer risk in hispanic and non-hispanic white women. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(5):442–50. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.5.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rowland TW. Promoting physical activity for children’s health: rationale and strategies. Sports Med. 2007;37(11):929–36. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737110-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brown WJ, Burton NW, Rowan PJ. Updating the evidence on physical activity and health in women. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(5):404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Morris JN, Hardman AE. Walking to health. Sports Med. 1997;23(5):306–32. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199723050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]