Abstract

As the major site of self-nonself discrimination in the immune system, the thymus, if successfully transplanted, could potentially carry with it the induction of central tolerance to any other organ or tissue from the same donor. We have recently developed a technique for transplantation of an intact, vascularized thymic lobe (VTL) in miniature swine. In the present study, we have examined the ability of such VTL allografts to support thymopoiesis and induce transplantation tolerance across fully MHC-mismatched barriers. Six miniature swine recipients received fully MHC-mismatched VTL grafts with a 12-day course of tacrolimus. Three of these recipients were thymectomized before transplantation and accepted their VTL allografts long-term, with evidence of normal thymopoiesis. In contrast, three euthymic recipients rejected their VTL allografts. Donor renal allografts, matched to the donor VTL grafts, were transplanted without immunosuppression into two of the three thymectomized recipients, and one of the three euthymic recipients. These renal allografts were accepted by thymectomized recipients, but rejected by the euthymic recipient in an accelerated fashion. This study thus demonstrates that successful transplantation of a vascularized thymus across a fully MHC-mismatched barrier induces tolerance in this preclinical, large-animal model. This procedure should enable studies on the role of the thymus in transplantation immunology as well as offer a potential strategy for tolerance induction in clinical transplantation.

Keywords: thymus transplantation, vascularization

The clinical application of organ transplantation is currently limited by a critical shortage of donor organs, as well as by the requirement for chronic, nonspecific immunosuppressive therapy for the remainder of a patient's life. Therefore, new strategies directed toward both the supply of organs and the induction of tolerance, have become major goals in the field of transplantation immunology. The induction of tolerance to transplanted organs or tissues could avoid the morbidity associated with prolonged immunosuppression. The extension of tolerance-inducing regimens from allogeneic to xenogeneic barriers holds the additional promise of alleviating the worldwide shortage of organs. Therefore, tolerance induction strategies have represented a major goal of preclinical transplantation research.

As the origin of T cell immunity, the thymus has the unique potential to tolerize allogeneic and/or xenogeneic responses to transplanted organs and tissues (1). This laboratory has previously reported a strategy for the induction of xenogeneic immunological tolerance in the pig-to-mouse model by directly transplanting nonvascularized porcine thymic tissue beneath the renal capsular space of mice (2, 3). However, attempts to perform similar nonvascularized thymic tissue transplants in large animals have had limited success (1, 4). Therefore, by using miniature swine as a large-animal model, the potential of vascularized thymic tissue to induce tolerance has been examined. Vascularized thymic transplants were initially performed by prevascularization of autologous thymic tissue grafts within a kidney's subcapsular space (prepared as single-donor composite grafts: thymokidneys). We have recently reported the ability of these composite grafts to induce allogeneic tolerance (1, 5, 6), suggesting that prevascularization of the thymic tissue before transplantation was crucial for success in large animals (1, 6).

Although thymokidneys were able to induce tolerance (1, 6), the full potential of vascularized thymus transplantation will only be realized if the scope of its applicability can be broadened to additional organs, less amenable to the preparation of composite grafts. In this regard, the ability to perform thymus transplantation as an isolated vascularized thymic lobe (VTL) graft could permit thymic-facilitated tolerance induction with any solid organ or tissue transplanted simultaneously. We recently reported our first attempts to perform VTL transplantation across minor mismatched barriers in Massachusetts General Hospital miniature swine, and have demonstrated that (i) the technique of VTL transplantation in swine can be performed successfully, and (ii) minor antigen-mismatched VTL allografts have the ability to support thymopoiesis (7).

Given our initial success across minor antigen-mismatched barriers, we have now extended our work to a greater antigenic disparity. We report here the successful application of VTL graft transplantation to the induction of tolerance and thymopoiesis across two-haplotype, fully MHC-mismatched barriers in thymectomized miniature swine recipients. Our data indicate that VTL grafts induce donor-specific systemic tolerance while maintaining immunocompetence to third-party antigens. Our results also demonstrate that the host thymus interferes with the induction of tolerance in this model. We believe that this technique offers a promising strategy to support long-term thymopoiesis and to induce transplantation tolerance across allogeneic or even xenogeneic barriers.

Materials and Methods

Animals. Animals were selected from our herd of MHC-inbred miniature swine (8, 9) at 2-4 months of age (juvenile animals) to serve as VTL donors, and swine of 3-6 months of age were used as recipients.

Experimental Groups. Six recipient pigs received two-haplotype fully MHC-mismatched VTL grafts. Three of these animals (group A) were completely thymectomized 3 weeks before transplantation whereas the other three (group B) remained euthymic.

Immunosuppressive Therapy. Tacrolimus (FK506; Fujisawa, Deerfield, IL) was administered for 12 days, starting on the day of transplantation (day 0). In an attempt to minimize side effects associated with high peak levels, the drug was infused continuously through an infusor pump (Baxter Health Care, Deerfield, IL). Dosing was started at 0.15 mg per kg per day and was subsequently adjusted to maintain a blood level of 30-40 ng/ml. Whole-blood levels were determined by microparticle enzyme immunoassay (Tacrolimus II, IMx system, Abbott Laboratories).

Surgery. Complete thymectomy in the recipient. Complete thymectomy was performed before allogeneic transplantation in three recipients as described (10). Briefly, the pretracheal muscles were retracted, exposing the cervical thymus and trachea from the cervicothoracic junction to the mandibular area. The cervical thymus was excised, after which the mediastinal thymus was removed through a sternotomy.

VTL transplantation. The procedure of VTL graft transplantation has been reported (7). Two animals in group A (thymectomized), and two animals in group B (nonthymectomized) had VTL grafts transplanted to the s.c. neck space by using the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein; in the remaining two recipients VTL grafts were transplanted in the retroperitoneum by using the abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava. This transplantation technique provided the VTL grafts with an immediate blood supply.

Biopsy of the VTL allografts. Biopsies were carried out on days 0, 30, 60, and >100. Approximately 1 × 0.5 × 0.5 cm of thymic tissue was biopsied for histology (formalin and frozen samples) and flow cytometric analysis.

Kidney transplantation. The procedure of kidney transplantation has been reported (10). Both native kidneys were removed on the day of kidney transplantation.

Preparation of Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes (PBLs). Blood was drawn from the external jugular vein at the time of biopsy. For separation of PBLs, freshly heparinized whole blood was diluted ≈1:2 with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) (GIBCO/BRL), and the mononuclear cells were obtained by gradient centrifugation using lymphocyte separation medium (Organon Teknika, Durham, NC). The mononuclear cells were washed once with HBSS, and contaminating red cells were lysed with ammonium chloride potassium buffer (B&B Research Laboratory, Fiskeville, RI). Cells were then washed with HBSS and were resuspended in tissue culture medium. All cell suspensions were kept at 4°C until used in cellular assays.

Preparation of Thymocytes. Parts of the biopsied tissue from thymic grafts (100-200 mg) were finely minced with a scalpel blade and were then dispersed with a syringe plunger into HBSS buffer. The cell suspension was then filtered through 200-μm nylon mesh, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in flow cytometry media.

Histological Examination. Formaldehyde-processed specimens were stained by using hematoxylin/eosin and periodic acid/Schiff reagent stains, and frozen samples were used for immunohistochemical analysis with the avidin-biotin horseradish-peroxidase complex technique (5).

Flow Cytometry. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of PBLs and thymocytes was performed by using a Becton Dickinson FACScan (San Jose, CA). Cells were stained by using directly conjugated murine mAbs, which were the same as those used for immunohistochemistry (see below). Phenotypic analysis of cells was performed by three-color staining. The staining procedure was performed as follows: 1 × 106 cells were resuspended in flow cytometry buffer (HBSS containing 0.1% BSA and 0.1% NaN3) and were incubated for 30 min at 4°C with saturating concentrations of a FITC-labeled mAb. After two washes, the secondary phycoerythrin-conjugated Ab was added and cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C. After a further wash, the final biotinylated Ab was added and incubated for 30 min. The cells were washed, and cytochrome was added for an 8-min incubation to stain the biotinylated Ab. Cells were then washed twice and were analyzed by FACScan.

Abs for Detection of Thymopoiesis and Peripheral Chimerism. Thymocyte development and peripheral chimerism were assessed by immunohistochemistry and FACS analyses using the murine anti-pig mAbs 74-12-4 (IgG2b, anti-swine CD4), 76-2-11 (IgG2a, anti-swine CD8), 76-7-4 (IgG2a, anti-swine CD1) (11), MSA4 (IgG2a, anti-swine CD2, BB23-8E6 (IgG2b, anti-swine CD3), 2-27-3a (IgG2a, anti-swine class I), and 10-9 [anti-swine pig allele-specific antigen (PAA) (12)].

Cell-Mediated Lymphocytotoxicity (CML) Assay. CML assays were performed as described (10, 13-15). Briefly, lymphocyte cultures containing 4 × 106 responder and 4 × 106 stimulator PBLs (irradiated with 2,500 cGy) per ml were incubated for 6 days at 37°C in 7.5% CO2 and 100% humidity. Bulk cultures were harvested and effectors were tested for cytotoxic activity on 51Chromium (Amersham Pharmacia)-labeled lymphoblast targets. The results were expressed as percent specific lysis (PSL), calculated as:

|

Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction (MLR) Assays. MLR assays were performed by plating 4 × 105 responder peripheral blood mononuclear cells in triplicate in 96-well flat bottom plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) (16). Cells were stimulated with 4 × 105 stimulator peripheral blood mononuclear cells irradiated with 2,500 cGy. Cultures were incubated for 5 days and 3H-thymidine was then added for an additional 6 h of culture.

Results

All VTL grafts were successfully transplanted, and different sites of transplantation did not appear to affect graft function. The VTL grafts turned pink within 2 min after completion of vascular anastomoses.

VTL Grafts Supported Thymopoiesis and Induced Tolerance in Thymectomized Hosts (Group A) but Failed to Do So in Euthymic Hosts (Group B). All three thymectomized animals were followed for >3 months. Two of these animals subsequently received kidneys MHC-matched to the VTL grafts without immunosuppression, 2-3 months after VTL transplantation.

The first euthymic animal rejected its VTL graft acutely and was killed on day 34, showing both histological (fibrosis and mononuclear cell infiltrate) and immunological (positive MLR and CML) evidence of sensitization. The second animal died on day 62 from sepsis secondary to an indwelling catheter infection, and also demonstrated histological evidence of VTL graft rejection. The third animal showed histological evidence of VTL graft rejection in the day 30 biopsy. Transplantation of a kidney matched to the VTL graft was performed on day 120 in this animal (see below).

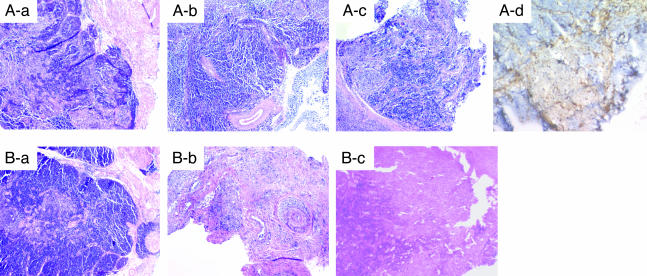

Histological Examination of VTL Grafts in Thymectomized and Euthymic Hosts. Fig. 1A demonstrates representative findings of biopsy specimens from group A recipients. As seen in Fig. 1, the VTL graft biopsy specimens at day 14 demonstrated intact thymic structure, with both cortex and medulla being well preserved. These VTL grafts remained intact in all subsequent biopsies, showing no evidence of rejection at any time. Immunohistochemistry by using an anti-donor MHC class I allele-specific Ab revealed many donor type class I-positive thymocytes in the medullary area of the VTLs graft on day 14, but the number of these cells markedly decreased by day 30 (data not shown). By day 60, there were no donor class I-positive thymocytes in the medullary thymus, but donor class I-positive thymic stromal cells (epithelial cells and morphologically dendritic-like cells) were still observed (Fig. 1 Ad).

Fig. 1.

Representative histology of VTL grafts stained with hematoxylin/eosin. Successive biopsies from thymectomized (A) and euthymic (B) hosts on days 14 (Aa and Ba), 30 (Ab and Bb), and 60 (Ac and Bc). Immunohistochemical staining of a thymectomized recipient with anti-donor MHC class I Abs on day 60 (Ad).

Long-term followup (day 259) of a VTL graft specimen from a thymectomized recipient demonstrated a macroscopically atrophic gland, with a thin cortical structure noted histologically; however, thymic structure was still maintained, including the presence of Hassall's corpuscles (data not shown). The changes observed could be due to the natural aging process, because naiïve thymus of age-matched swine had the same appearance (data not shown).

Fig. 1B demonstrates representative findings of biopsy specimens from group B recipients. As for group A recipients, day 14 biopsies showed intact cortical and medullar structures within the VTL, indicating the technical success of both groups of recipients. However, in contrast to the thymectomized recipients in group A, biopsy specimens on day 30 from euthymic hosts showed hypocellular thymic tissue, chronic vasculopathy with associated intimal hyperplasia, and a mononuclear cell infiltrate (Fig. 1Bb), all indicative of graft rejection. Autopsy or biopsy specimens of the VTL grafts on day 62 (autopsy) and day 70 (biopsy) in two of the three remaining euthymic hosts showed diffuse fibrosis.

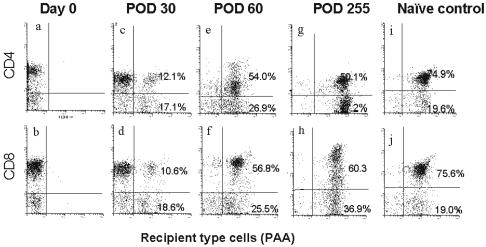

Thymopoiesis Assessed by FACS. Three-color FACS analysis following VTL transplantation was carried out to determine whether thymopoiesis of recipient-type cells occurred after migration into the donor VTL graft. PAA-positive pigs were used as recipients and PAA-negative pigs were used as the VTL graft donors. Unfortunately, PAA as a marker for immunohistochemical analysis was difficult to use due to its calcium dependence (17). However, in contrast to the class I allele-specific Ab, which detects only mature thymocytes (18), the PAA Ab allowed for the characterization of recipient type CD4- and CD8-positive thymocytes, including most immature thymocytes.

Fig. 2 demonstrates thymopoiesis within the donor VTL graft after transplantation to one of the thymectomized recipients. The results obtained from this animal were representative for all group A animals. The phenotypic analyses of PAA-positive/CD4 and PAA-positive/CD8 thymocytes, isolated following thymic biopsy (Fig. 2), showed donor thymocytes to be PAA-negative. Following transplantation, PAA/CD4 double-positive cells and PAA/CD8 double-positive cells were detected by day 30 FACS analysis. The number of these recipient-type cells markedly increased by day 60 with a phenotypic pattern at day 60 similar to that seen in the naiïve recipient thymus (PAA-positive) removed 3 weeks before VTL transplantation. Thympoiesis continued long-term after VTL transplantation, indicating that both CD4 and CD8 host T cells developed in the fully MHC-mismatched donor VTL grafts. In addition, the majority of these cells were CD1-positive (Fig. 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) and CD4/CD8-double-positive (Fig. 4c), confirming their identity as thymocytes. Approximately 30% of the total thymocytes expressed CD3 (Fig. 4a), indicating active maturation occurring in the VTL graft similar to that seen in the recipient naiïve thymus removed 3 weeks before transplantation (Fig. 4b). The number of CD3-positive thymocytes on day 255 was higher than that seen at earlier time points from a thymectomized recipient, which is consistent with the histological evidence of widening of the medullary thymus. In addition, CD1 single-positive cells decreased over time; however, CD1/CD3 double-positive cells increased with time, indicating that thymopoiesis continued at later time points. (data not shown)

Fig. 2.

FACS analysis of thymocytes in VTL grafts. Analysis of successive biopsies from a representative PAA(-) VTL graft transplanted into a thymectomized PAA(+) pig. On the day of transplant (day 0), all cells were negative for PAA staining (a and b). The pattern of staining became progressively more similar to that of the naiïve PAA(+) control thymus (i and j) on days 30 (c and d), 60 (e and f), and 255 (g and h).

Results of FACS analysis for euthymic recipients were consistent with the histologic findings, and demonstrated no thymopoiesis within the VTL grafts on day 30 thymic biopsies. The thymic grafts were hypocellular. There was a lack of host CD1 cells in the VTL graft specimens, and the majority of the mononuclear cells were host CD3-positive cells. The phenotypic analysis observed by FACS was consistent with the presence of graft infiltrating cells causing rejection of the VTL grafts (data not shown).

Macrochimerism. Macrochimerism, defined as chimerism that is readily detectable by FACS analysis of PBLs, was evaluated in two of the three thymectomized recipients of group A. Both animals showed donor cell macrochimerism on day 14, which increased by day 60 (Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Further analysis of the phenotypic pattern of these donor cells (Fig. 5Ac) showed that two-thirds were CD3-positive. It is likely that these donor cells originated and emigrated from the transplanted graft, allowing for peripheral detection by FACS analysis after transplantation.

Macrochimerism in the peripheral blood of the euthymic recipients was low, compared with the levels in thymectomized recipients of VTL grafts. On day 14, group B recipients had fewer donor class I-positive cells in lymphocyte-gated populations (Fig. 5Ba and Bb), compared with thymectomized recipients of VTL grafts (Fig. 5Aa and Ab). Thereafter, the macrochimerism in euthymic recipients of VTL grafts disappeared by day 60, most likely secondary to rejection of the grafts. (data not shown)

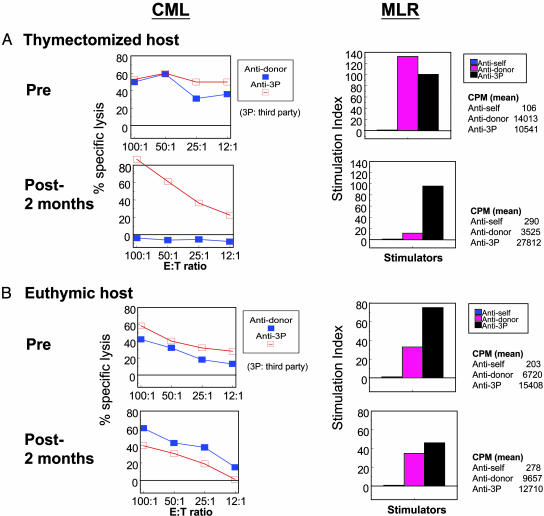

Immunological Status. Fig. 3A demonstrates representative data for group A animals in CML and MLR assays. These animals showed anti-donor-specific unresponsiveness on day 30, whereas anti-third-party allogeneic responses were present, but were relatively weak (data not shown). By day 60, anti-third-party responses returned to normal strength, whereas anti-donor unresponsiveness remained in both CML and MLR assays. These data indicated that VTL allografts induced donor-specific unresponsiveness in thymectomized recipients, while maintaining immunocompetence in vitro to third-party stimulation.

Fig. 3.

In vitro responses from representative CML and MLR assays. (A) Thymectomized animals developed anti-donor-specific unresponsiveness after transplantation in both MLR and CML assays. (B) Euthymic recipients failed to develop donor-specific unresponsiveness.

CML and MLR assays in euthymic recipients demonstrated that the VTL grafts failed to induce donor-specific unresponsiveness. One animal had a stronger CML and MLR response against donor antigens than against third-party antigens on day 28, indicating sensitization (data not shown). This animal was killed on day 34 to obtain complete histological analysis.

The other two animals showed general hyporesponsiveness on day 30 (data not shown); however, these animals went on to develop anti-donor CTL responses by day 60 (Fig. 3B).

Renal Allograft Transplantation in Thymectomized and Euthymic Recipients of VTL Grafts to Test Donor-Specific Tolerance. We next examined whether group A recipients, which were long-term acceptors of VTL grafts with evidence of donor-specific unresponsiveness in vitro, would be systemically tolerant in vivo. Renal allografts MHC-matched to the original donor VTL grafts (therefore, two-haplotype, fully MHC-mismatched to the recipients) were transplanted without immunosuppression in two of the three recipients, 3-4 months after VTL transplantation. Both recipients accepted these renal allografts, with one animal demonstrating stable renal function after kidney transplantation (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), and only minimal cellular infiltrate by histological analysis (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). In the second animal, the creatinine rose on day 25, although other clinical parameters of rejection were absent. Therefore, an emergency laparotomy was performed, and the ureter of the transplanted kidney was found to have become twisted, secondary to a fibrous adhesion involving the animal's ovary. As shown in Fig. 6A, the plasma creatinine levels decreased immediately after repair of the ureter. A biopsy specimen on the day of ureterovesicular reanastomosis showed only a focal mononuclear cell infiltrate without vasculitis (data not shown), indicating mechanical failure, not rejection, as the source of the rise in creatinine. Creatinine levels remained stable for the next 2 months, at which time the kidney was removed and a third-party renal allograft was transplanted as a specificity control (see below).

The same two group A recipients that had received renal allografts MHC-matched to the original donor VTL grafts, were tested further for immunocompetence by transplantation of a third-party renal allograft without immunosuppression 3 or 6 months after the first kidney transplants. The ureter of the donor-matched renal allograft was tied during the transplantation procedure in the first animal to permit assessment of third-party renal allograft function while still being able to observe histological changes might occur in the tolerant kidney due to third-party renal allograft transplantation. The donor-matched kidney in the second animal was removed to make space for the third-party kidney graft, and histology of this donor-matched allograft showed only a minimal cell infiltrate (data not shown). Both recipients rejected these third-party kidneys within 9 days with severe histological evidence of cellular and humoral rejection (Fig. 7c), indicating immunocompetence to third-party antigens. At the time of third-party kidney graftectomy, the VTL donor-matched renal allograft in the first animal showed no evidence of rejection (Fig. 7b).

A renal allograft MHC-matched to the original donor VTL graft (therefore two-haplotype, fully MHC-mismatched to the euthymic recipient) was transplanted without immunosuppression 4 months after the initial VTL transplant in one of the euthymic recipients. As shown in Fig. 6B, this animal rejected the kidney graft on day 4 in an accelerated fashion, indicative of prior sensitization to donor antigen by VTL graft transplantation. Histologically, the kidney graft showed a diffuse mononuclear cell infiltrate with severe vasculitis and fibrinoid necrosis (data not shown). These data confirmed that the host thymus interfered with the induction of tolerance by donor VTL graft transplantation across a fully MHC-mismatched barrier.

Discussion

VTL transplantation has the potential to permit the cotransplantation of any organ or tissue, and therefore greatly expands the general applicability of thymus transplantation, as compared with composite thymokidney transplantation (5). In addition to its tolerance-inducing capabilities, the thymopoietic capacity within the VTL graft has the potential to supply a form of T cell reconstitution to immunodeficient individuals, such as those infected with HIV. To our knowledge, we believe the present study to be the first demonstration of tolerance induction, and supporting thymopoiesis, by VTL graft transplantation in a fully allogeneic large-animal model. Our data indicate (i) that VTL grafts induce donor specific systemic tolerance while maintaining immunocompetence to third-party antigens, and (ii) that the presence of a juvenile host thymus interferes with the induction of tolerance.

Two mechanisms, which could act in concert, seem plausible as immunologic events that allow the vascularized thymic graft to induce tolerance. The first mechanism involves thymic stromal cells, and possibly dendritic cells, in the VTL graft that may induce central tolerance after transplantation by achieving deletion or anergy of T cells reactive to the donor haplotype (19). The second potential mechanism involves thymic emigrants from the VTL graft, which could be responsible for the induction of tolerance by means of a peripheral mechanism of regulation that leads to the silencing of alloreactive cells. Such peripheral tolerance could be mediated by a change in cytokine milieu or by the generation of another regulatory T cell population (20, 21). Further investigations will be required to determine whether either of these mechanisms is responsible for the induction of transplantation tolerance in the present study. Future experiments involving the transplantation of irradiated VTL grafts, indicating that thymic stromal cells may play an important role in the induction of tolerance, are warranted.

We have shown that the presence of a host thymus interferes with the induction of tolerance. This finding is similar to that previously reported in mice, reported by our colleagues (2), in which euthymic animals failed to develop tolerance to pig antigens after receiving porcine thymic grafts, as compared with thymectomized mice that demonstrated stable tolerance. It seems that a period is required for the donor VTL graft to clonally delete or anergize newly developing host thymocytes that are reactive to donor antigens. Host thymectomy presumably extinguishes the production of new alloreactive T cells, while the 12-day course of FK506 silences those cells already present peripherally. The combination of these two effects may permit a selective advantage for the donor VTL graft to not only be accepted but also to begin the process of tolerizing the host to donor antigen. In addition, mature T cells already present peripherally could enter the donor thymic graft. Reentry of activated T cells into the host thymus has been reported (22, 23), and a similar mechanism of reentry could be operating in allogeneic VTL grafts. It would thus seem that thymectomy would be essential for the successful induction of tolerance by VTL grafts, especially in juvenile recipients with active host thymic function. However, because complete thymectomy may not be acceptable in clinical transplantation, thymic irradiation may serve as a less invasive alternative to complete thymectomy.

The blood levels of FK506 used in this study have been reported by our group to induce tolerance to fully mismatched renal allografts in miniature swine (16). Although these levels are high for chronic use in a clinical setting, continuous infusions of high-dose FK506 have been used, without serious complications, for short periods (3-5 days) after ABO-incompatible renal transplantation (24), and for acute graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation (25). Toxicities caused by those high levels for short periods are generally reversible (24).

In our allogeneic and xenogeneic thymokidney studies, as well as in reports from rodent studies, the ability of the thymic graft to induce tolerance depended on complete T cell depletion (3, 6). In our present investigation of VTL transplantation, we demonstrated that thymectomy alone without T cell depletion, was sufficient to allow for tolerance induction, even though residual recipient T cell populations survived in the periphery. Because the thymic graft in the mouse model was nonvascularized, a greater extent of T cell depletion may have been required during the period of revascularization to minimize alloreactive T cell responses. The high level of T cell depletion in the mouse model would allow for the thymus graft to assume gradual function without succumbing to T cell-mediated rejection. Our own allogeneic thymokidney studies required T cell depletion in the form of both thymectomy and an anti-CD3 immunotoxin (6). We believe that the greater reduction of T cell numbers afforded by the anti-CD3 immunotoxin was required because the amount of vascularized thymic tissue present beneath the kidney capsule was much less than that in transplanted VTL grafts. The larger amount of thymic tissue present in VTL grafts may have a greater capacity to induce either anergy or deletion of residual circulating alloreactive T cells that enter the graft (22, 23), therefore allowing for the induction of tolerance, with thymectomy serving as the only form of T cell depletion.

The induction of transplantation tolerance remains an important goal for clinical transplantation, and the path to achieving this goal will require a clear understanding of the role of the thymus in the induction of tolerance. In addition to its potential clinical applications for allogeneic and xenogeneic tolerance induction, we believe the technique of VTL transplantation will offer a promising strategy for further this understanding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Yong-Guang Yang and Katsuhito Teranishi for their helpful review of the manuscript; Scott Arn for herd management and quality control typing; Maria J. Doherty for assistance in manuscript preparation; and Fujisawa Healthcare, Inc. (Deerfield, IL) for generously providing FK506. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants 5RO1 AI31046, 5PO1 HL18646, 5PO1 AI39755, and 5PO1 AI45897, and by an unrestricted educational grant from Fujisawa Healthcare, Inc. P.A.V. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Medical Student Research Fellow.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: CML, cell-mediated lymphocytotoxicity; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorter; FK506, tacrolimus; HBSS, Hanks' balanced salt solution; MLR, mixed lymphocyte reaction; PAA, pig allele-specific antigen; PBL, peripheral blood lymphocyte; VTL, vascularized thymic lobe.

References

- 1.Yamada, K., Shimizu, A., Utsugi, R., Ierino, F. L., Gargollo, P., Haller, G. W., Colvin, R. B. & Sachs, D. H. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 3079-3086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee, L. A., Gritsch, H. A., Sergio, J. J., Arn, J. S., Glaser, R. M., Sablinski, T., Sachs, D. H. & Sykes, M. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 10864-10867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao, Y., Rodriguez-Barbosa, J. I., Swenson, K., Barth, R. N., Shimizu, A., Arn, J. S., Sachs, D. H. & Sykes, M. (2000) Transplantation 69, 1447-1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haller, G. W., Esnaola, N., Yamada, K., Wu, A., Shimizu, A., Hansen, A., Ferrara, V. R., Allison, K. S., Colvin, R. B., Sykes, M., et al. (1999) J. Immunol. 163, 3785-3792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamada, K., Shimizu, A., Ierino, F. L., Utsugi, R., Barth, R., Esnaola, N., Colvin, R. B. & Sachs, D. H. (1999) Transplantation 68, 1684-1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada, K., Vagefi, P. A., Utsugi, R., Kitamura, H., Barth, R., LaMattina, J. C. & Sachs, D. H. (2003) Transplantation 76, 530-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaMattina, J. C., Kumagai, N., Barth, R. N., Yamamoto, S., Kitamura, H., Moran, S. G., Mezrich, J. D., Sachs, D. H. & Yamada, K. (2002) Transplantation 73, 826-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lunney, J. K., Pescovitz, M. D. & Sachs, D. H. (1986) in Swine in Biomedical Research, ed. Tumbleson, M. E. (Plenum, New York), pp. 1821-1836.

- 9.Sachs, D. H., Leight, G., Cone, J., Schwartz, S., Stuart, L. & Rosenberg, S. (1976) Transplantation 22, 559-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamada, K., Gianello, P. R., Ierino, F. L., Lorf, T., Shimizu, A., Meehan, S., Colvin, R. B. & Sachs, D. H. (1997) J. Exp. Med. 186, 497-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pescovitz, M. D., Lunney, J. K. & Sachs, D. H. (1984) J. Immunol. 133, 368-375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuchimoto, Y., Huang, C. A., Shimizu, A., Seebach, J., Arn, J. S. & Sachs, D. H. (1999) Tissue Antigens 54, 43-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirkman, R. L., Colvin, R. B., Flye, M. W., Williams, G. M. & Sachs, D. H. (1979) Transplantation 28, 24-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pescovitz, M. D., Lunney, J. K. & Sachs, D. H. (1985) J. Immunol. 134, 37-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kortz, E. O., Sakamoto, K., Suzuki, T., Guzzetta, P. C., Chester, C. H., Lunney, J. K. & Sachs, D. H. (1990) Transplantation 49, 1142-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Utsugi, R., Barth, R. N., Lee, R. S., Kitamura, H., LaMattina, J. C., Ambroz, J., Sachs, H. & Yamada, K. (2001) Transplantation 71, 1368-1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, C. A., Lorf, T., Arn, J. S., Koo, G. C., Blake, T. & Sachs, D. H. (1999) Xenotransplantation 5, 201-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schuurman, H.-J., van de Wijngaert, F. P., Huber, J., Schuurman, R. K. B., Zegers, B. J. M., Rood, J. J. & Kater, L. (1985) Hum. Immunol. 13, 69-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sprent, J., Lo, D., Gao, E. K. & Ron, Y. (1988) Immunol. Rev. 101, 173-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakaguchi, S. (2000) Cell 101, 455-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Modigliani, Y., Coutinho, A., Pereira, P., Le Douarin, N., Thomas-Vaslin, V., Burlen-Defranoux, O., Salaun, J. & Bandeira, A. (1996) Eur. J. Immunol. 26, 1807-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agus, D. B., Surh, C. D. & Sprent, J. (1991) J. Exp. Med. 173, 1039-1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gopinathan, R., DePaz, H. A., Oluwole, O. O., Ali, A. O., Garrovillo, M., Engelstad, K., Hardy, M. A. & Oluwole, S. F. (2001) Transplantation 72, 1533-1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi K. (2001) in ABO-Incompatible Kidney Transplantation, ed. Takahashi, K. (Elsevier, Amsterdam), pp. 128-143.

- 25.Ohashi, Y., Minegishi, M., Fujie, H., Tsuchiya, S. & Konno, T. (1997) Bone Marrow Transplant 19, 625-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.