Many public health educators have noted the rapid growth and proposed sustainability of undergraduate programs in public health.1,2 Several educators have also articulated the reasons for developing such programs,3,4 most notably in the 2003 Institute of Medicine Report, “Who Will Keep the Public Healthy?,”5 and the kinds of students who are attracted to them.6 Administrators of graduate programs in public health can safely assume that their students are primarily interested in either practice or research in the health sciences. Therefore, it is reasonable that the curricular and co-curricular expectations are designed to produce competent public health practitioners with an adequate understanding of research. Such an assumption cannot be made, however, about students who enroll in undergraduate public health programs.

Undergraduate public health programs across the country are attracting students who will enter the public health workforce or continue to graduate school in the health sciences. Undergraduate training in public health can help to address the looming public health workforce shortage by preparing students for entry-level positions.6,7 In addition, many students study public health because it is an interesting field that provides a foundation for a future outside of the health sciences. The critical thinking of social sciences, the mechanistic knowledge of hard sciences, and the real-world application of allied health professions can all be found in an undergraduate public health curriculum.4

The proliferation of undergraduate public health programs is changing public health education. The consistency that the public health community has come to expect from Master of Public Health (MPH) programs, especially with the advent of competency-based curricula, will likely not be possible with the flourishing of undergraduate programs. Allowing for diversity at the undergraduate level, even a diversity that inevitably complicates our efforts, is the best way to serve our students and the field of public health.

PHILOSOPHIES OF UNDERGRADUATE PUBLIC HEALTH PROGRAMS

There are several strategies for incorporating public health into general undergraduate studies: individual courses, minors, and academic majors.6,8,9 In this article, we are concerned with academic majors—whether connected to schools of public health or not. Based on our analysis, two major philosophies are emerging related to the academic majors: programs within a liberal arts framework and programs within a practice-based framework.10,11

Liberal arts framework

An undergraduate public health degree can emerge quite naturally out of the liberal arts tradition. A liberal arts degree is not designed to graduate students competent in any particular skill set but to produce educated citizens who are able to apply skills of -critical and creative thinking and communication in any number of situations.11 A liberal arts degree in public health adds the value of experiential learning, intercultural competence, ethical reasoning and action, and interdependent teamwork.4,11 Liberals arts degrees can lead a student directly to employment in a wide variety of fields or can serve as a pre-professional degree. Such degrees require a broad-based core curriculum, and the multidisciplinary nature of public health lends itself well to this kind of study.

A purely liberal arts framework, however, has its challenges. Nearly all stakeholders in higher education are increasingly concerned with the linkage between obtaining a degree and gaining meaningful employment. This linkage is harder to make with liberal arts degrees than it is with business, clinical, or technical degrees. Moreover, the training of public health faculty and the lens through which education has traditionally been viewed have been practice oriented. Therefore, if the undergraduate degree is emerging out of an established graduate-level program, public health faculty may be uncomfortable with the significant differences associated with a liberal arts education. On the other hand, if the undergraduate degree is emerging out of a liberal arts faculty who are trained to teach in this manner, the challenge becomes whether they have the depth of public health knowledge necessary to deliver the content of a public health degree.

Practice-based framework

The practice-based framework for undergraduate public health education is also understandable. With a tradition of practice-based education at the graduate level, competency-based curricula, and faculty trained to teach from a practice-based perspective, it is reasonable to want to replicate success and capitalize on expertise for expansion at the undergraduate level. Public health is an inherently action-oriented discipline, which is a major part of the attraction for students at all levels. In addition, the public health workforce will be in need of replenishment in the years to come,12,13 and producing well-trained undergraduates can be a cost-effective way for supply to meet demand,6 a fact especially true in areas of the country where graduate degrees are uncommon and the public health needs are particularly pronounced.

Nevertheless, a purely practice-based framework has its own challenges. The most obvious comes from the need to differentiate undergraduate and graduate practice-based degrees. Programs that require undergraduate students to have 30 or more hours of practice-based coursework will inevitably create substantial overlap with graduate programs. In addition, such a focus could miss opportunities to expose talented students interested in pursuing careers other than public health practice to the applicability of public health for people in any discipline. It is no secret within the field that public health suffers from a lack of understanding among the public. An undergraduate degree program narrowly focused to attract future public health practitioners may solve one problem while ignoring another.

BLENDING LIBERAL ARTS AND PRACTICE-BASED PHILOSOPHIES

Pursuing either a purely liberal arts or purely practice-based program may make sense for some programs. A college or university with a mission to serve the needs of the local population may choose a practice-based approach because its area has a low density of trained public health professionals and such a program can help ameliorate that problem. A college or university with a student body that typically pursues graduate education may choose liberal arts because their students who are interested in practicing public health will subsequently pursue a practice-based graduate degree. These and many other reasons may drive a program's decision to track in one direction or the other.

There is also great value in developing a program that blends liberal arts and practice-based philosophies. A blended program has the opportunity to attract a great diversity of students. If students see myriad possibilities with a degree in public health (as evidenced by graduates pursuing many different paths), there is a likelihood of bringing together students from diverse backgrounds with distinct interests. A blended program also has the ability to draw on existing strengths within a faculty while inviting new possibilities, such as collaboration in core curriculum classes with other departments. A blended program also finds a middle ground between the competing philosophies of education—that of learning as a means to an end and the other of learning as an end unto itself. This middle ground fits well with the ethos of public health as a discipline that recognizes health as having intrinsic value and as being an instrumental good.4

At Saint Louis University, we have attempted to create a blended program. Because the interdisciplinary nature of public health has been a key dimension to public health's success for our undergraduate program, we have intentionally placed value on liberal arts and practice-based work. As a relatively new academic program housed in the College for Public Health and Social Justice, we have taken lessons from the strong liberal arts core of the College of Arts and Sciences (hereafter, A&S) and the practice-based curriculum of the College of Nursing and the College of Allied Health Professions. The blending of liberal arts and practice-based work not only occurs across the curriculum (e.g., Introduction to Global Health focuses on the values of public health while Contemporary Issues in Global Health focuses on the practice of public health) but also within coursework itself (e.g., Public Health and Social Justice requires students to evaluate public health interventions for their effect on vulnerable populations but also articulate why attention to vulnerable populations is an inherently desirable value).

Developing learning outcomes

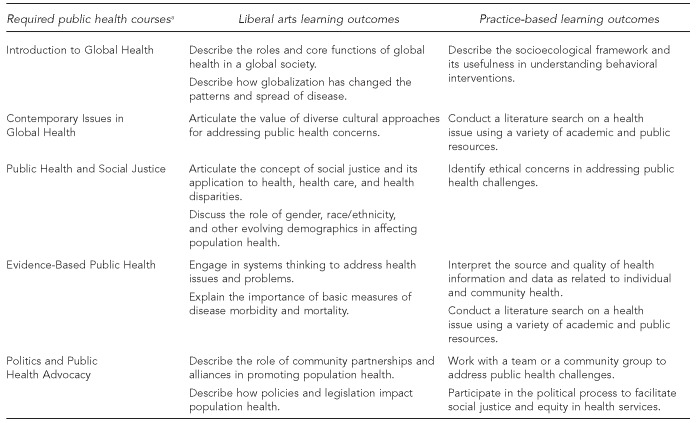

When developing the curriculum, two types of learning outcomes emerged. Some outcomes were oriented around specific actions (e.g., “conduct a literature search” or “work with a team”), while others were general knowledge-based learning outcomes that we contextualized in public health (e.g., “articulate the value” of social justice and its application to health, health care, and health disparities; or “engage in systems thinking” to address health issues and problems). The Figure lists the liberal arts and practice-based learning outcomes for five of the public health courses. Certainly, one cannot separate action from the theory that underlies it, nor can an educated citizen be so without action. The two are not entirely separable. However, as we refine our curriculum, we attempt to include some learning outcomes in each course that emphasize public health practice and some that use public health theory as a lens for broad-based (liberal arts) thinking.

Figure.

Selected liberal arts and practice-based learning outcomes in undergraduate public health coursework at Saint Louis University

aRequired for students pursuing a Bachelor of Science in Public Health. All listed courses also have service-learning requirements, which have liberal arts and practice-based dimensions.

As a way of integrating this balance, four of the first six undergraduate courses require a substantial commitment to service learning. Service learning is enjoying a renaissance in higher education and provides learning outcomes that range from “understanding and application of subject-matter learning” to “citizenship skills and values.”14 To help achieve these outcomes, our faculty facilitate individual/small-group reflection and require written assignments on the connections between classroom concepts and community experiences. In so doing, we develop a resonance between what they do and who they are. A mutual reinforcement of these ideas, we believe, is a vital reason for blending practice-based and liberal arts education.

As a Jesuit, Catholic university, Saint Louis University draws upon a rich history of “contemplation in action.”15 Typical of the Jesuit tradition in education, our university mission statement speaks of the “knowledge and skills required to transform society.” Knowledge is both self-knowledge that emerges from critically engaging the world as well as material knowledge that comes from classroom settings. The skills are not only about what to do but also the discerning wisdom of when, why, and how to do it. All practice-oriented degrees at Saint Louis University are expected to have a liberal arts core curriculum, and academic majors are expected to integrate the values of the liberal arts into the major-related coursework. Therefore, a blended liberal arts and practice-based approach is natural for our academic environment.

Students in A&S, the largest college at Saint Louis University, are required to take two classes on diversity as part of their core curriculum. One class must focus on global citizenship, and the other class should focus on diversity in the United States. Introduction to Global Health, the foundation course for students in the College for Public Health and Social Justice, has been approved to fulfill the global citizenship requirement for A&S students, and Public Health and Social Justice meets the A&S requirement for diversity in the United States. These two courses, required for every public health undergraduate student, are also valued by faculty in the humanities for the courses' ability to help students think about the way health, culture, and community inform how we behave as educated citizens—a liberal arts dimension. At the same time, non-majors are exposed to practice-based methods of public health through these courses. This cooperation with the humanities helps faculty in public health better understand the liberal arts and also advances the goals of the widely accepted Liberal Education and America's Promise framework to educate students for responsible citizenship within a global economy.11

The blended nature of the program at Saint Louis University has been a key factor in the diversity of students who are not public health majors or minors who choose to take public health courses as electives during their undergraduate studies. Introduction to Global Health and Public Health and Social Justice attract a wide variety of students. Theology and philosophy majors take the courses as supplements to their liberal arts degree. Nursing and physical therapy majors take the courses as additions to their clinical, practice-oriented programs. Additionally, exposure from one course often results in students changing majors and minors from political science, economics, sociology, biology, and many other programs to public health. Changes are not necessarily because students have discarded an old passion for a new one, but because they find public health to be an interesting application of longstanding interests.

Challenges of a blended program

The blending of liberal arts and practice-based curricula at Saint Louis University is not without its challenges. Many students enjoy the action-oriented nature of public health, so it can sometimes be difficult to create value for reflection and theory when they are in the midst of community projects. Yet, insisting on a depth of philosophical reflection, no matter how resistant students or faculty might be, in the end will produce more thoughtful and creative practitioners. It can be challenging to find a balance in course content, assessment methods, and service-learning expectations so that they meet the needs of students who want to be public health practitioners and students who see public health as a good social science foundation for other careers. In the end, both groups as well as faculty can be dissatisfied if the philosophy of the program is not properly explained. To address this challenge, we regularly gather as undergraduate faculty to review course content and assessment methods, and assure that they adequately cover public health learning outcomes. Moreover, we try to ensure faculty have the necessary resources to successfully transition from graduate-level practice-based education to undergraduate-level education more characterized by liberal arts. Providing necessary resources is done to exchange best practices and to ensure we maintain a balanced curriculum.

MOVING THE CONVERSATION FORWARD

Graduate-level programs in public health have achieved a consistency in philosophy because of the expectations of their accrediting body. This consistency is appropriate because employers and colleagues have a right to expect certain knowledge and skills from anyone with an MPH. A baccalaureate degree in public health, however, should not search for this level of consistency. The flexibility to meet the many different needs of undergraduate students should remain even if undergraduate programs go through an accreditation process.

The recently completed Undergraduate Public Health Learning Outcomes Model, developed by the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH) in collaboration with the Association of American Colleges and Universities, the Association for Prevention -Teaching and Research, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has both liberal arts and practice-based dimensions.16 The inclusion of a capstone experience that can be tailored to a student's future plans is a good sign that even a largely liberal arts-based program will require students to apply knowledge gained in the classroom in a community-based setting.

Allowing for this flexibility will lead to the benefits associated with the three types of programs described previously. One consideration might be the difference between a Bachelor of Arts (BA) in Public Health and a Bachelor of Science (BS) in Public Health. Although we at Saint Louis University value the blended nature of our program, other programs that tend to one end of the spectrum or the other might consider naming a liberal arts degree a BA and a practice-oriented degree a BS. Accrediting bodies might also consider retaining flexibility in curriculum development and learning outcomes by differentiating between the two degrees.

This discussion has obvious implications not only for the future of undergraduate programs but also for the future of graduate programs.17 Most graduate curricula are currently designed assuming that students enter with very little formal background in public health. It will be necessary to ensure that students who have an undergraduate background in public health do not unnecessarily repeat content. Rather, strategies for eliminating redundancy will have to reflect the difference in types of undergraduate programs. Graduate programs will not be able to waive or substitute classes simply based on whether or not a student has a degree in public health, as undergraduate programs will emphasize different types of knowledge and competence. The need for articulation between the undergraduate and graduate degrees has been discussed previously,10 and ASPPH has embarked on a project to set the future direction for public health education, which will naturally help to define the articulation.16

In an attempt to respond to these changes, Saint Louis University has begun the articulation discussion and developed an accelerated BS/MPH program. Although our coursework is blended throughout, it generally moves from liberal arts to practice-based coursework as students progress through the curriculum. In so doing, students' senior year is primarily practice-based, and many courses are borrowed from the first year of the graduate program (e.g., biostatistics, epidemiology, and behavioral science). This reconfiguring of courses allows capable students to achieve an MPH in five years. It also allows students who earn a baccalaureate degree without continuing into the fifth year of studies to emerge with a liberal arts foundation (i.e., the first several semesters of coursework), as well as the basics of public health practice (i.e., overlapping courses taken in the fourth year of studies).

An accelerated degree is not a universal solution because many undergraduate programs are emerging at universities that do not have accredited graduate programs in public health.8 Modeling undergraduate program development off of graduate program development and accreditation could have a stifling effect on these and other programs at a time when public health is positioned to gain a larger role in public consciousness. Discussions will continue about the growth of undergraduate programs, the difference between and the articulation of undergraduate and graduate programs, and the accreditation of undergraduate programs. Openness to different models right now will provide the necessary data to make more informed decisions in the future.

REFERENCES

- 1.Petersen DJ. Public health learning outcomes for all undergraduates. Divers Democr. 2011;14:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riegelman RK, Garr DR. Healthy People 2020 and Education for Health: what are the objectives? Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:203–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riegelman RK. Undergraduate public health education: supporting the future of public health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13:237–8. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000267680.93034.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koh HK, Nowinski JM, Piotrowski JJ. A 2020 vision for educating the next generation of public health leaders. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:199–202. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine (US), Board on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, Committee on Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st century. Who will keep the public healthy? In: Gebbie K, Rosenstock L, Hernandez LM, editors. Educating public health professionals for the 21st century. Washington: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnold LD, Schneider D. Advising the newest faces of public health: a perspective on the undergraduate student. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1374–80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bass SB, Guttmacher S, Nezami E. Who will keep the public healthy? The case for undergraduate public health education: a review of three programs. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14:6–14. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000303407.81732.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hovland K, Kirkwood BA, Ward C, Osterweis M, Silver GB. Liberal education and public health: surveying the landscape. Peer Rev. 2009;11:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown D. For a global generation, public health is a hot field. The Washington Post. 2008 Sep 19; [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JM. Articulation of undergraduate and graduate education in public health. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 2):12–7. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riegelman RK. Undergraduate public health education: past, present, and future. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:258–63. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gebbie K, Merrill J, Hwang I, Gebbie EN, Gupta M. The public health workforce in the year 2000. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003;9:79–86. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenstock L, Silver GB, Helsing K, Evashwick C, Katz R, Klag M, et al. Confronting the public health workforce crisis: ASPH statement on the public health workforce. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:395–8. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eyler J, Giles DE., Jr . Where's the learning in service-learning? San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barry WA, Doherty RJ. Contemplatives in action: the Jesuit way. Mahwah (NJ): Paulist Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Association of Schools of Public Health, Association of American Colleges and Universities, Association for Prevention Teaching and Research, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Undergraduate public health learning outcomes model. Washington: ASPH; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleming ML, Parker E, Gould T, Service M. Educating the public health workforce: issues and challenges. Aust N Z Health Policy. 2009;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1743-8462-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]