In its seminal 1988 report, “The Future of Public Health,” the Institute of Medicine (IOM) called public health “what we do as a society collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy.”1 Public health interventions may occur in myriad institutions, through a variety of direct and indirect mechanisms in communities across the country. Yet, despite the many proven benefits of health approaches based on prevention and the well-being of populations, public health does not enjoy popular support and is poorly understood by most Americans.2 The dominance of medical solutions to health challenges, even in the face of overwhelming evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based preventive approaches, is illustrative of this broad lack of understanding. In 2003, the IOM suggested that the nation's health would benefit from a greater understanding of the profession's potential. To promote this enhanced awareness among the public, the IOM report called for every undergraduate to have access to education in public health.3

This call for broader public health education led to the formation of the Educated Citizen and Public Health initiative led by the Association for Prevention Teaching and Research, the Council of Colleges of Arts and Sciences, the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH), and the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U). The initiative intended to respond to growing demand in the field and bring leadership to the suddenly explosive growth of courses and programs. The initiative further intended to introduce undergraduate study of integrative public health to all institutions of higher education and to take an interdisciplinary and inter-professional approach to collaboration.4

In recognition of the growth in undergraduate public health programs at colleges and universities, many without schools or programs of public health, ASPPH determined that it should actively engage in defining the learning outcomes and design of undergraduate public health programs. Many questions immediately surfaced: Should the traditional liberal arts be the recommended framework? Should programs prepare associate and baccalaureate graduates to enter the workforce? Should curricula include an internship or apprenticeship? Should programs focus on lifelong learning? How would an undergraduate public health degree articulate to existing master's degrees in public health? And what faculty development opportunities would be needed to support the integration of public health theory and content into other areas of inquiry in an undergraduate setting? In September 2009, ASPPH convened an Undergraduate Task Force to consider these issues and to develop a strategy for integrating public health knowledge and principles in undergraduate education.

TASK FORCE GOALS AND OUTCOMES

The ASPPH Undergraduate Task Force included representatives from Council on Education for Public Health-accredited schools and programs, AAC&U, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The group considered various approaches to guidance for existing and emerging undergraduate public health programs, including responses to the demand for clear guidelines for the structure and content of undergraduate public health majors. The meaning and approach to the need for an educated citizenry in response to the IOM's call likewise demanded attention. The task force concluded that there was a need for an educated citizenry and subsequently drafted a set of learning outcomes that could be used to infuse public health concepts into the existing undergraduate curriculum and co-curriculum.

The group was further inspired by the AAC&U Liberal Education and America's Promise (LEAP) initiative,5 a 10-year effort to transform 21st-century undergraduate education, addressing a set of essential learning outcomes and a commitment to highly effective engaged or high-impact educational practices. The LEAP framework readily supports and addresses the objectives of public health learning and is philosophically attuned to public health. AAC&U surveys indicate that the LEAP essential learning outcomes represent consensus in the field of undergraduate education; therefore, their potential to support learning in public health is considerable.6,7 The essential learning outcomes for all undergraduates include knowledge of human cultures and the physical and natural world, intellectual and practical skills, personal and social responsibility, and integrative and applied learning. These outcomes call for undergraduates to engage in learning that seeks inter- and multidisciplinary answers to unscripted real-world problems.

Armed with the IOM call, the Educated Citizen and Public Health effort, and the LEAP framework, the task force was inspired to advance the public's knowledge of public health over time by reaching young adults while they are in college. The task force determined that the effort would be broadly focused on educating all undergraduates about public health, and that the audience would then necessarily be faculty, students, and administrative leaders in two- and four-year institutions. Hence, the group chose to use the essential learning outcomes framework of the AAC&U LEAP initiative rather than a more traditional public health framework to organize its work. The group further elected to develop a set of public health learning outcomes within the first three domains of the LEAP framework (knowledge, skills, and personal and social responsibility) and to return to the fourth domain—integrative and applied learning—after the first three domains had been populated with public health content, concepts, tools, and values.

The learning outcomes within each of these three domains were developed by a 10-member workgroup that included an equal number of representatives from the liberal arts and sciences and from public health. Cochairs represented each constituency. To accommodate the numerous people who wanted to participate, resource groups were created to support each appointed workgroup; in total, more than 130 people contributed to the development of undergraduate public health learning outcomes.

The workgroups that were formed around the first three domains developed a core set of learning outcomes within each domain, using an online modified Delphi approach to propose, consider, vet, and specify learning outcomes. Workgroup members offered as many suggested learning outcomes as they wished. Each workgroup culled the list in the first Delphi round following the modified Delphi survey results and corresponding workgroup discussion. Workgroup members voted to keep, discard, or modify each item and, in the ensuing discussion, duplicate items were eliminated, similar items were consolidated, and the highest-ranking items were retained and rephrased as deemed appropriate by the workgroup. For rounds two and three, workgroup members were joined by the resource groups in carefully considering and selecting the best set of learning outcomes through a similar voting approach.

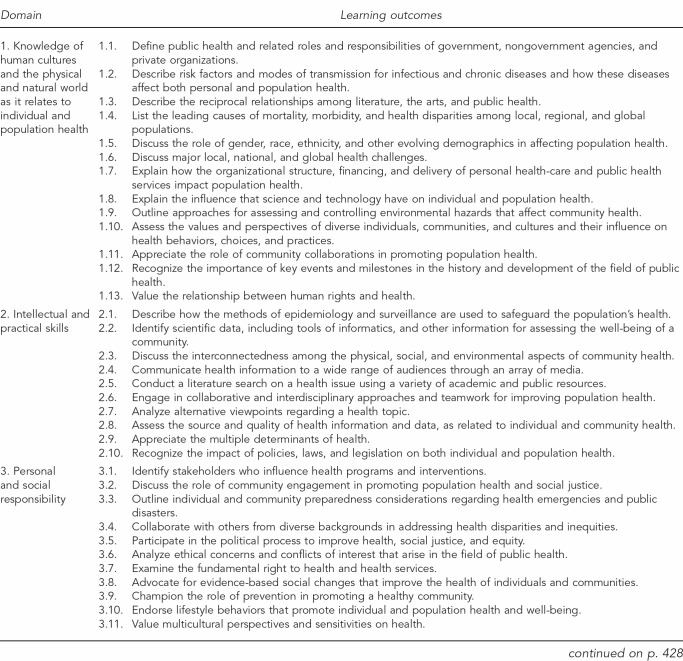

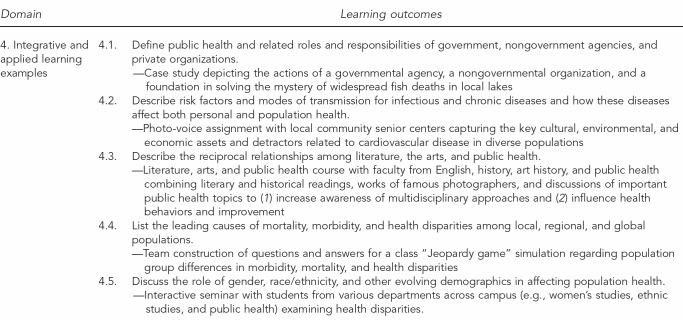

From an initial list of 394 potential learning outcomes, the workgroups agreed on a set of 34 recommended learning outcomes (Figure), representing what the overall group believed all undergraduates, as educated members of society, should know and be able to do to promote their own and their communities' health. The concepts and skills articulated in these 34 learning outcomes are not intended to be prescriptive but selected as appropriate and integrated meaningfully into curricular and co-curricular learning opportunities. The list is not exhaustive; rather, it provides illustrative examples of how public health contributes to quality of life locally and globally. In addition, it illustrates how the science and art of public health can enhance understanding of the essential learning outcomes, as well as promote adoption of the LEAP framework in undergraduate education. This approach was designed for simplicity and flexibility in deployment. The learning outcomes do not call for a particular course or a specified curriculum; instead, they provide opportunities for the diffusion of knowledge across an existing set of educational experiences.

Figure.

Members of the Undergraduate Public Health Education Expert Panel convened by the Association of Schools of Public Health to specify critical component elements of an undergraduate major in public health: 2011a

aDeveloped in collaboration with the Association of American Colleges and Universities and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A complete list of domains and outcomes can be found on the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health website at: http://www.asph.org/userfiles/learningoutcomes.pdf

Learning outcomes

The 13 learning outcomes selected within the first domain—knowledge of human cultures and the physical and natural world as it relates to individual and population health—cover a variety of topics relevant to the humanities and the sciences. Some outcomes focus directly on public health knowledge, including its definition, governmental roles, and sentinel events in the development of the field. Other outcomes encourage an appreciation of community collaboration and an understanding of how diverse demographics within a community influence health. The outcomes invite comparisons of factors at the local, national, and global levels, including environmental hazards, risk factors for infectious and chronic diseases, and the leading causes of death. They further promote valuing the relationships among human rights and health, science and technology and health, and medical and public health services and health. One particular learning outcome, unique to this domain, points to the reciprocal relationships among literature, the arts, and public health.

The second domain—intellectual and practical skills—contains 10 learning outcomes that together focus on understanding health information and data and the methods of discovering and investigating related evidence; appreciating the multiple determinants of health and the interconnectedness of the physical, social, and environmental aspects of -community health, including the impact of policies, laws, and legislation; and developing skills in research, analysis, teamwork, and communication.

The 11 learning outcomes in the third domain—personal and social responsibility—range from endorsing prevention and promoting healthy lifestyle behaviors to engaging in both community-level health-promotion activities and the political process. Also included in this domain are ethics and social justice, the confluence of individual rights and the greater social good, diversity, valuing multicultural perspectives, and collaborating across the social spectrum to improve public health.

Developing the specific learning outcomes within these domains was a challenging and invigorating process. When the group progressed to considering the fourth domain—integrative and applied learning—the level of discovery rose even higher. The ways in which learning outcomes are applied contributes to the actual learning, skill development, and appreciation that will occur among undergraduate students and the faculty that embrace their incorporation into curricula. Public health shines in this area because so much of what is accomplished in public health is carried out through integrative and applied approaches.

Domain four provides innovative and dynamic ways to integrate and apply the 34 learning outcomes from the first three domains in both in-classroom and out-of-classroom settings. For example, the focus of learning outcome four, domain two (intellectual and practical skills) is to “communicate health information to a wide range of audiences through an array of media.” One way this outcome could be accomplished under domain four might be to engage a group of journalism students to develop a multimedia public information campaign promoting influenza vaccines among older adults. Students would need to understand the influenza virus, why a new vaccine is developed every year, why older adults are particularly susceptible to influenza, how that susceptibility translates into premature mortality and costly hospitalizations, and how that result impacts society at large. They would learn how health messaging and social marketing differ from other communication strategies and could be used to engage local health-care, public health professionals, and the media to complete this project.

Similarly, a political science or public policy class could stage a mock town hall meeting in which various stakeholders, including the local hospital, police department, school board, and leading employers in the community, review the latest health status report prepared by the local health department and consider approaches to improving health outcomes in the community. This activity would also address learning outcome one, domain three, “identify stakeholders who influence health programs and interventions.” While the workgroup members were able to identify examples for every one of the 34 learning outcomes, it is more important that examples of the integration and application of the learning outcomes come directly from those using the learning outcomes in their educational settings. In this way, the adoption of undergraduate public health learning outcomes remains dynamic and fluid, leading to a continuously expanding knowledge base of ways to achieve the IOM's call for every undergraduate to be exposed to education in public health. Suggestions and examples on using the learning outcomes are welcome at -learningoutcomes@aspph.org.

The benefits of a better-educated citizenry

If one can imagine a future in which greater numbers of people understand and appreciate public health and value its contributions to their lives, one can also envision a number of possible scenarios. It could be less common for college-educated people to argue against fluoridation of municipal water systems or the promotion of healthy foods in school cafeterias. And it could be more common for people to demand better access to safe places for recreation, work-site wellness programs, or more consistent information about the performance of health facilities and providers in their communities. Expectations could evolve regarding improved consumer information, better labeling, enhanced accessibility to data, more walking and bike trails, increased efficiencies in public transportation, more open green spaces and community gardens, added openness to discussing various health-care reform strategies, as well as greater compassion and understanding of needs for those who become ill or disabled.

In addition to the overall benefits that could accrue from a better-educated citizenry, the public health workforce could potentially have a much larger pool from which to fill critical positions. State and local agencies and other institutions engaged in public health work are often willing to offer internships or, in some locales, employment to undergraduates with some knowledge of public health, even if their major is in a different field. Having undergraduates with a working knowledge of public health in other employment sectors should enhance the effectiveness of our overall systems and improve our success in efforts to promote community health. Finally, graduate schools and programs should benefit from a more informed applicant pool seeking advanced public health degrees and may be challenged to upgrade graduate-level courses and curricula in response.

Launching the initiative

Like many public health interventions, this initiative shows that developing the tool is the easy part; the challenge is in its adoption and implementation.8 For the undergraduate public health learning outcomes to achieve their ultimate vision, they must be actively incorporated into learning opportunities in and outside of classrooms in two- and four-year institutions of higher education across the country. Public health professionals can contribute in many meaningful ways to realize this goal.

The primary audience for this effort includes colleges and universities without schools or programs of public health. As such, interested faculty and students will be looking for public health expertise in their communities. Local and state health agency personnel are a natural resource for this effort, as they bring not only a set of fundamental knowledge and skills but also important and timely issues that can be addressed by interested groups of students and faculty. Community-based public health professionals could provide guest lectures, lead discussions, host field trips, mentor individuals or groups of students, review student projects, supervise short-term internships, or advise student organizations that are interested in community health.

Faculty or student organization advisors in two- and four-year institutions who are interested in exploring relationships with local public health professionals should reach out to these individuals and agencies. The National Association of County and City Health Officials and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials provide online directories to state and local health agencies and officials. Similarly, public health professionals can also be found in hospitals and long-term care facilities; in mental health, substance abuse, and homeless programs; in laboratories, schools, pharmacies, and health-care institutions; and in voluntary and professional organizations. Other community-based agencies such as law enforcement, fire departments, water and waste management, pollution control, and highway safety are often engaged in public health work and can be excellent resources for discussing public health issues through a variety of disciplines.

Students who are interested in the undergraduate learning outcomes can engage faculty in developing interesting ways to incorporate material within existing courses in all disciplines and fields. They can also use student organizations or create venues for adapting learning outcomes to various community or campus-based projects. Likewise, they can access social media to engage in discussions of how learning outcomes are reflected in current events, both on campus and in the larger community. They can further invite local, state, national, or international public health leaders to address the campus community on topics of particular interest to them. Finally, students who are interested in building their public health knowledge can create portfolios demonstrating their achievement of a set of learning outcomes.

CONCLUSION

For the first time, the most recent set of health objectives for the nation, Healthy People 2020, includes an objective directly related to undergraduate public health education.9 It is clear that increased collaboration and concerted efforts need to be deployed to promote a deeper understanding of public health and its implications in communities around the country and around the world. Not everyone needs a degree in public health, but the benefits of public health enhancements to curricula in every discipline are evident. A better-educated public, a better-educated workforce, and a more cohesive community response to public health and health-care challenges are all worth the effort to engage academicians and professionals from across the disciplinary spectrum. Public health is a social and economic imperative, and we can no longer afford to hold this knowledge within our profession. The time is now to work toward a truly educated citizenry if we are to achieve our health objectives and our humanitarian ideals.

Footnotes

This article was supported under a cooperative agreement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH) grant #CD300430. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. The future of public health. Washington: National Academy Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor H. New York: Louis Harris and Associates, Inc.; 1997. “Public health:” two words few people understand even though almost everyone thinks public health functions are very important. Harris Poll # 1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebbie K, Rosenstock L, Hernandez LM, editors. Who will keep the public healthy? Educating public health professionals for the 21st century. Washington: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association of American Colleges and Universities. The educated citizen and public health. [cited 2012 Feb 2]. Available from: URL: http://www.aacu.org/public_health/index.cfm.

- 5.Association of American Colleges and Universities. Liberal Education and America's Promise (LEAP) [cited 2012 Feb 2]. Available from: URL: http://www.aacu.org/leap/index.cfm.

- 6.Association of American Colleges and Universities. National survey of AAC&U members (2009) [cited 2012 Feb 2]. Available from: URL: http://www.aacu.org/membership/membersurvey.cfm.

- 7.New Leadership Alliance for Student Learning and Accountability. Committing to quality: guidelines for assessment and accountability in higher education. [cited 2012 Feb 2]. Available from: URL: http://www.newleadershipalliance.org/what_we_do/committing_to_quality.

- 8.Calhoun JG, Spencer HC, Buekens P. Competencies for global health graduate education. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2011;25:575–92. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Healthy people 2020. [cited 2013 May 10]. Available from: URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx.