Abstract

Aims:

To assess the sensitivity and specificity of right subcostal ultrasound view to confirm correct endotracheal tube intubation (ETT).

Materials and Methods:

In this prospective study, apneic or paralyzed patients who had an indication of intubation were selected. Intubation and ventilation with bag were performed by the skilled third-year emergency medicine residents. The residents, following a brief training course of ultrasonography, interpreted the diaphragm motion, and identified either esophageal or tracheal intubation. The confirmation of ETT placement was done by the sonographer. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy were calculated for tracheal versus esophageal intubation.

Results:

A total of 57 patients aged 59 ± 5 who underwent ETT insertion were studied. Thirty-four of them were male (60%). Ultrasound correctly identified 11 out of 12 esophageal intubations for a sensitivity of 92% (95% CI = 62-100), but misidentified one esophageal intubation as tracheal. Sonographers correctly identified 43 out of 45 (96%) tracheal intubations for a specificity of 96% (95% CI = 85-99), but misdiagnosed two tracheal intubations as esophageal.

Conclusions:

This study suggests that diaphragm motion in right subcostal ultrasound view is an effective adjunct to diagnose ETT place in patients undergoing intubation in emergency department.

Keywords: Diaphragm motion, endotracheal tube intubation, ultrasound

INTRODUCTION

Intubation with endotracheal tube (ETT) is the key management of airway control in emergency situations.[1,2]

Endotracheal intubation has an approximate failure rate of 8%.[3] Unrecognized intubation of the esophagus is relatively infrequent, but is followed by morbidity and mortality.[4,5,6]

Direct visualization of an endotracheal tube passing through vocal cords into the trachea during intubation is a proper confirmation of correct tube placement. However, when a patient has a Cormack and Lehane scoring of 3 or 4,[7] the vocal cord aperture is not easily visible; therefore, it is always necessary to confirm ETT intubation with a secondary technique.[8,9]

There are many described techniques for confirming correct ETT intubation, including the colorimetric capnography, negative pressure devices, visualization of a condensed vapor settled on a tube, and chest radiography. However, each of them has its own limitations and none of them are ultimate.[3,10,11,12] Although capnography has high sensitivity and specificity, it has false-negative results in severe airway obstructions, low cardiac output, serious hypotension, and pulmonary emboli.[13]

Ultrasound is an accessible, convenient, fast, portable, relatively inexpensive, pain-free, and safe method that offers the confirmation of ETT independent of the patient's physiology. Frontal and lateral walls of almost all upper airway segments are visible by the ultrasound either partially or completely.[14] The material of an endotracheal tube which is mainly plastic is hyperechoic, which makes it distinguishable from the surrounding tissues and facilitates the visualization.

Ultrasound can quickly and efficiently visualize the motion of the diaphragm and pleura, which are indirect quantitative and qualitative indicators of lung expansion indirectly.[15,16] If ETT is placed in a correct position, bilateral motion of the diaphragm toward the abdomen can be visible.[17] Besides, by intercostal view, simultaneous motion of the pleura with ventilation can be viewed as a lung sliding sign.[18]

In this study, we assessed the sensitivity and specificity of the diaphragm motion in right subcostal ultrasound view in confirmation of the correct intubation in the setting of an emergency department (ED).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study setting was the ED of a large teaching hospital. The subject group included patients admitted in the ED that had the indication of intubation for any reason. Candidates who were awake and had been spontaneously breathing after intubation were excluded; only apneic or paralyzed patients were selected to view their diaphragm motion only with artificial ventilation. Moreover, patients who had cardiopulmonary arrest were excluded from the study, because the accurate control of their conditions was impossible.

The third-year emergency medicine residents familiar with the general application of emergency ultrasound performed ultrasound imaging after an initial training. The training consisted of 1-hour course of upper abdomen ultrasound imaging, especially diaphragm and liver. The confirmation of ETT placement was done by the sonographer. The other residents were skilled in ETT placement and could properly identify esophageal intubation. All procedures were supervised by an emergency medicine attending.

The intubation was performed using a 7.5 or 8.0-mm ETT and direct laryngoscopy for visualization of the glottis.

Following the rapid sequence intubation, the patients were ventilated with the bag by residents and ultrasonography was simultaneously performed. The ultrasonographer and intubator did not communicate with each other all through the trial.

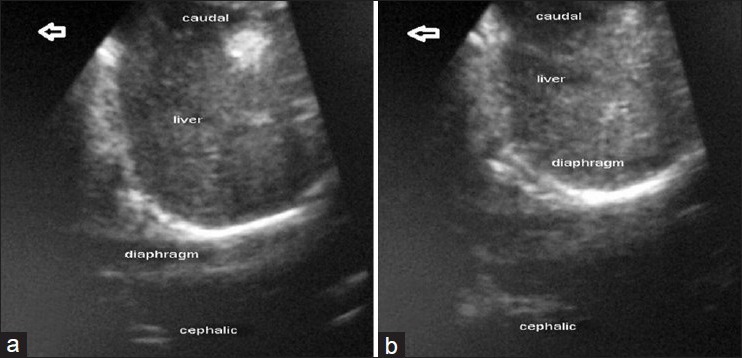

A portable ultrasound machine, Fukuda Denshi 4300R (Type: Portable Ultrasound; Brand Name: FUKUDA DENSHI; Place of Origin: Japan; Model Number: FF Sonic UF-4300R) with a 3.5-MHz curved probe, was used. The probe was placed in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, exactly below the edge of the ribs with a 45 degree angle toward the chest near the midclavicular line. The probe was toward the right side of the patient [Figure 1]. This view provides a suitable vision of the liver and echogenic diaphragm [Figure 2a]. During positive pressure via ventilation with bag (inspiratory phase), diaphragm motion toward the abdomen was registered as an intratracheal intubation. In contrast, the observation of diaphragm motion toward chest or non-significant motion was in favor of esophageal intubation [Figure 2b].

Figure 1.

Position of the probe on the patient's abdomen

Figure 2.

(a) Diaphragm view in the right subcostal area before ventilation. (b) right side diaphragm position during the positive-pressure ventilation

In all patients, postintubation evaluations like pulse-oximetry and auscultation were performed simultaneously with ultrasound. If the ultrasound view supported esophageal intubation or equivocal ultrasound findings, and the intubator was not sure about seeing the tracheal tube passing via the vocal cords, the patient would be immediately evaluated with repeated laryngoscopy by an emergency physician. If the laryngoscopy confirmed esophageal placement, the patient would be extubated, re-intubated, and the previous intubation would be set as an esophageal intubation. In case the sonographer reported tracheal intubation and pulse-oximetry and auscultation confirmed it, no laryngoscopy was performed and the patient was under control by pulse-oximetry and heart monitoring for 15 minutes. When the oxygen saturation did not drop or the hemodynamic of the patient was stable during the 15 minutes, it was registered as successful ETT placement. In cases when the intubator was sure about seeing the passage of ETT via the vocal cords, the final confirmation was set as the correct tracheal intubation. Finally, X-ray was taken for diagnosing right bronchus intubation after confirming the intubations.

Statistical analysis

Sensitivity and specificity were calculated with 95% confidence interval (CI). Results were generated using a STAT_DAG excel spreadsheet.[19]

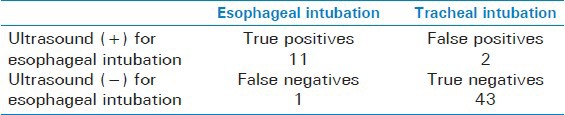

A 2-by-2 table was used to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of the ultrasonography to help identify tracheal and esophageal tube placement.

Approval

Approval was obtained from Local Research Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Our study conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

Thirty-four (60%) men and 23 (40%) women were enrolled in the study. The average age was 59 ± 5 years.

The ultrasound identified 11 out of 12 correctly placed esophageal intubations for a sensitivity of 92% (95% CI = 62-100), but misidentified one esophageal intubation as tracheal.

The sonographers correctly identified 43 out of 45 (96%) tracheal intubations for a specificity of 96% (95% CI = 85-99), but misdiagnosed two tracheal intubations as esophageal. The positive predictive value was 85% (95% CI = 55-98) with the negative predictive value of 98 (95% CI = 55-98). The accuracy was 95% (95% CI = 85-99). The values are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Ultrasound identification of esophageal vs. tracheal intubation

DISCUSSION

The American College of Emergency Physicians recommends the confirmation of correct ETT placement in all patients at the time of initial intubation. They assert that an ultrasound may be useful as an adjunct to identify and monitor the proper location of ETT. However, enough evidence is unavailable to support the widespread implementation of it.[9] Pfeiffer, et al.[20] in their study manifested that ETT placement with ultrasound is faster than the standard method of auscultation and capnography and is as fast as auscultation alone.

Although the observation of the chest rise, the auscultation of the abdomen and lungs, and visualizing “misting” in the ETT are the primary confirmation of ETT, these are mistaken in 30% of inexperienced examiners and are highly dependent on one's skill. Therefore, it is rational to use secondary methods to confirm the proper placement of ETT intubation.[13]

Capnography seems to be the most sensitive tool as the secondary method with the sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 97%.[13]

Studies have evaluated the role of ultrasound in non-emergency situations.[20,21,22,23] Our study was worthy of note, because it was performed in a real emergency setting.

In previous studies, multiple views of ultrasound imaging have been used to confirm ETT placement: Vertical or horizontal transcricothyroidal,[23] suprasternal,[23,24] and lung sliding sign.[21,22] All of these studies support the sensitive use of ultrasound in ETT confirmation.

In addition, studies have shown that ultrasound can diagnose paralyzed diaphragm.[16,17] Therefore, it seems practical to detect diaphragm motion during the positive-pressure ventilation by using ultrasound imaging of it. Hsieh, et al. studied the use of diaphragm motion for confirmation of ETT correct placement on 59 children in prenatal intensive care unit (PICU) setting. They diagnosed all intubations correctly with ultrasound imaging with sensitivity and specificity of 100%; however, they had only two esophageal intubations.[25] Kerrey, et al.[26] used diaphragm motion view of ultrasound in confirmation of correct ETT placement in 66 children in PICU. They evaluated the diagnosis of right main bronchus intubation. In their study, the sensitivity and specificity were 88% and 64%, respectively. Although sensitivity and specificity of the ultrasound in our study were high, we cannot strongly state that the ultrasound is a sensitive and specific method, because the confidence interval for sensitivity and specificity were rather wide.

Studies have identified the intubation of the right main bronchus using diaphragm motion or observation of the lung sliding sign by placing the probe in the left side of the chest; however, left side of the chest is not as good as the right side for seeing the diaphragm motion.[22,26] If the patient is paralyzed or apneic, it would be suitable to evaluate the diaphragm motion in the right side of the chest to diagnose the esophageal intubation.

The passage of ETT using cricothyroidal ultrasound in a dynamic view has a high sensitivity and specificity; however, the sensitivity decreases following the intubation.[23]

It is not necessary to use the ultrasound throughout the procedure of intubation. Because we evaluate the diaphragm motion during the ventilation, the ultrasound is preferably used at the end of intubation.

Different areas of the body are available to evaluate ETT position. In emergency settings, performing ultrasonography in the neck area can disturb the process of intubation. In addition, performing transcricothyroidal or suprasternal ultrasonography needs more experience and a linear probe with a frequency of greater than 7.5 MHz which may not be found in the majority of EDs. Subcostal ultrasonography does not disturb the intubation process, because it is far from the intubation site. On the other hand, it needs less experience than the other sites. Therefore, it seems that in emergency situations, subcostal and intercostal views (sliding lung sign) are more applicable.

Because of the high-quality view of the diaphragm motion on the right side of the chest and less need for skill compared with the intercostal view, the right subcostal view could be a more suitable view for diagnosing correct tracheal intubation in ED.

One of the major limitations of using lung expansion in evaluation of correct ETT place is when the patient breathes spontaneously. These patients already have diaphragm motions during their inspirations. Therefore, it is better to utilize diaphragm motion in paralyzed, apneic, or bradypneic patients; moreover, a big mucus plug can prevent adequate lung expansion and can lead to false-positive ultrasound imaging supporting esophageal intubation. Although breathing would be a bias to diagnose the correct ETT placement, the extent of diaphragm motion in spontaneous breathing is totally different from a positive-pressure-supported breathing. As a result, further studies are needed to evaluate diaphragm motion quantitatively in a spontaneously breathing patient.

Limitations

The incidence of misplaced ETT intubation in ED is not obvious; however, studies based on out-of-hospital intubations reflect the rate of 6.7%[27] to 25%.[28] In our study, the esophageal intubation rate was not clear because of the high exclusion rate. Also, this method can fail to diagnose right bronchus intubations. Other methods like auscultation can be used as an adjunct in order not to miss the right bronchus intubation.

Another limitation of our study is that we did not confirm the correct place of ETT by capnometer. Although end-tidal carbon dioxide detection is the most accurate method to estimate ETT position, our study lacked this method.

CONCLUSION

This study suggests that diaphragm motion in right subcostal ultrasound view is a sensitive and specific secondary confirmatory method for diagnosing ETT place in apneic or paralyzed patients undergoing intubation in ED. Further studies should be performed to carry out more comparisons between methods.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Mr. Erfan Heidari and Mrs. Bita Pourmand for their careful edit of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Emergency Medicine Department of Shariati Hospital. Tehran University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: No.

REFERENCES

- 1.Graham CA, Brittliff J, Beard D, McKeown DW. Airway equipment in Scottish emergency departments. Eur J Emerg Med. 2003;10:16–8. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winchell RJ, Hoyt DB. Endotracheal intubation in the field improves survival in patients with severe head injury. Trauma Research and Education Foundation of San Diego. Arch Surg. 1997;132:592–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430300034007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grmec S. Comparison of three different methods to confirm tracheal tube placement in emergency intubation. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:701–4. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adriani J. Unrecognized esophageal placement of endotracheal tubes. South Med J. 1986;79:1591–3. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198612000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adriani J, Naraghi M, Ward M. Complications of endotracheal intubation. South Med J. 1988;81:739–44. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198806000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clyburn P, Rosen M. Accidental oesophageal intubation. Br J Anaesth. 1994;73:55–63. doi: 10.1093/bja/73.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cormack RS, Lehane J. Difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia. 1984;39:1105–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeBoer S, Seaver M, Arndt K. Verification of endotracheal tube placement: A comparison of confirmation techniques and devices. J Emerg Nurs. 2003;29:444–50. doi: 10.1016/s0099-1767(03)00268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verification of endotracheal tube placement. [Last accessed on 2013 Jan 08]. Available from: http://www.acep.org/Content.aspx?id=29846 and terms=Verification%20of%20Endotracheal%20Tube%20Placement .

- 10.Andersen KH, Schultz-Lebahn T. Oesophageal intubation can be undetected by auscultation of the chest. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1994;38:580–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1994.tb03955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knapp S, Kofler J, Stoiser B, Thalhammer F, Burgmann H, Posch M, et al. The assessment of four different methods to verify tracheal tube placement in the critical care setting. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:766–70. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199904000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vukmir RB, Heller MB, Stein KL. Confirmation of endotracheal tube placement: A miniaturized infrared qualitative CO2 detector. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:726–9. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)80831-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J. Capnography alone is imperfect for endotracheal tube placement confirmation during emergency intubation. J Emerg Med. 2001;20:223–9. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(00)00318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sustic A. Role of ultrasound in the airway management of critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:S173–7. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000260628.88402.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller NL. Imaging of the pleura. Radiology. 1993;186:297–309. doi: 10.1148/radiology.186.2.8421723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerscovich EO, Cronan M, McGahan JP, Jain K, Jones CD, McDonald C. Ultrasonographic evaluation of diaphragmatic motion. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:597–604. doi: 10.7863/jum.2001.20.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottesman E, McCool FD. Ultrasound evaluation of the paralyzed diaphragm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1570–4. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lichtenstein DA, Menu Y. A bedside ultrasound sign ruling out pneumothorax in the critically ill. Lung sliding. Chest. 1995;108:1345–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.5.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mackinnon A. A spreadsheet for the calculation of comprehensive statistics for the assessment of diagnostic tests and inter-rater agreement. Comput Biol Med. 2000;30:127–34. doi: 10.1016/s0010-4825(00)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfeiffer P, Rudolph SS, Borglum J, Isbye DL. Temporal comparison of ultrasound vs. auscultation and capnography in verification of endotracheal tube placement. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55:1190–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chun R, Kirkpatrick AW, Sirois M, Sargasyn AE, Melton S, Hamilton DR, et al. Where's the tube? Evaluation of hand-held ultrasound in confirming endotracheal tube placement. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2004;19:366–9. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00002004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weaver B, Lyon M, Blaivas M. Confirmation of endotracheal tube placement after intubation using the ultrasound sliding lung sign. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:239–44. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma G, Davis DP, Schmitt J, Vilke GM, Chan TC, Hayden SR. The sensitivity and specificity of transcricothyroid ultrasonography to confirm endotracheal tube placement in a cadaver model. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:405–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milling TJ, Jones M, Khan T, Tad-y D, Melniker LA, Bove J, et al. Transtracheal 2-d ultrasound for identification of esophageal intubation. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:409–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsieh KS, Lee CL, Lin CC, Huang TC, Weng KP, Lu WH. Secondary confirmation of endotracheal tube position by ultrasound image. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(9 Suppl):S374–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000134354.20449.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerrey BT, Geis GL, Quinn AM, Hornung RW, Ruddy RM. A prospective comparison of diaphragmatic ultrasound and chest radiography to determine endotracheal tube position in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e1039–44. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Timmermann A, Russo SG, Eich C, Roessler M, Braun U, Rosenblatt WH, et al. The out-of-hospital esophageal and endobronchial intubations performed by emergency physicians. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:619–23. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000253523.80050.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz SH, Falk JL. Misplaced endotracheal tubes by paramedics in an urban emergency medical services system. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:32–7. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.112098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]