Abstract

Little is known about how patterns of cell proliferation and arrest are generated during development, a time when tight regulation of the cell cycle is necessary. In this study, the mechanism by which the developmental signaling molecule Wingless (Wg) generates G1 arrest in the presumptive Drosophila wing margin is examined in detail. Wg signaling promotes activity of the Drosophila retinoblastoma family (Rbf) protein, which is required for G1 arrest in the presumptive wing margin. Wg promotes Rbf function by repressing expression of the G1-S regulator Drosophila myc (dmyc). Ectopic expression of dMyc induces expression of Cyclin E, Cyclin D, and Cdk4, which can inhibit Rbf and promote G1-S progression. Thus, G1 arrest in the presumptive wing margin depends on the presence of Rbf, which is maintained by the ability of Wg signaling to repress dmyc expression in these cells. In addition to advancing the understanding of how patterned cell-cycle arrest is generated by the Wg signaling molecule during development, this study indicates that components of the Rbf/E2f pathway are targets of dMyc in Drosophila. Although Rbf/E2f pathway components mediate the ability of dMyc to promote G1 progression, dMyc appears to regulate growth independently of the RBF/E2f pathway.

Despite many advances in our understanding of the molecules that regulate the cell cycle, comparatively little is known about how patterns of cell proliferation or cell-cycle arrest are generated during development (1). Current studies indicate that some of the same molecules responsible for regulating patterning and differentiation also regulate cell proliferation and growth. For example, in addition to regulating expression of target genes that mediate its ability to promote cell patterning and differentiation, the developmental signaling molecule Hedgehog (Hh) induces expression of Cyclins D and E during Drosophila development. Induction of these G1-S cyclins mediates the ability of Hh to drive cell growth and proliferation (2).

Wingless (Wg), a member of the Wnt family of secreted signaling proteins, functions as both a patterning molecule and a cell-cycle regulator during Drosophila development. The presumptive wing margin of the third-instar wing disk consists of a strip of cells located at the dorso-ventral boundary. Patterning of the margin, which will eventually contain an organized array of mechano- and chemosensory bristles, takes place during the third instar. This patterning process is regulated in part by Wg, which induces expression of proneural genes, such as achaete (ac) and scute (sc) (3, 4).

Before their differentiation as bristles, presumptive wing margin cells undergo cell-cycle arrest (5, 6). Because of the fact that this arrest occurs while most other wing disk cells are still cycling, the presumptive wing margin is often referred to as the zone of nonproliferating cells (ZNC). Notch promotes this arrest by sustaining Wg expression at the dorsal/ventral boundary. Wg-induced expression of ac and sc in the dorsal- and ventral-anterior regions of the ZNC induces G2 arrest (6). Ac and Sc promote G2 arrest in these cells by down-regulating expression of string, the Drosophila homologue of the mitosis-inducing phosphatase Cdc25. Thus, through induction of proneural gene expression, Wg functions to promote both patterning and G2 arrest in the dorsal and ventral anterior domains of the ZNC (6).

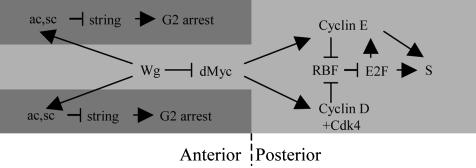

Although dorsal and ventral anterior ZNC cells arrest in G2, other ZNC cells, including central anterior and all posterior cells, arrest in G1 (ref. 6; Fig. 1A). In the anterior central region, Notch activity prevents G2 arrest by repressing ac and sc. Notch-dependent Wg expression is required to promote G1 arrest in the anterior central and posterior regions. Thus, although Wg is often associated with induction of cell proliferation (7, 8), in the wing, it can promote cell-cycle arrest (6). Recent studies also have indicated that Wg can constrain growth during Drosophila wing development (9).

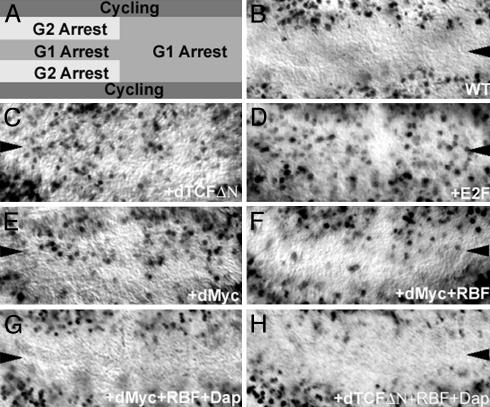

Fig. 1.

Rbf regulates G1 arrest in the ZNC. (A) Patterns of cell-cycle arrest induced by Wg in the Drosophila ZNC, adapted from ref. 6. (B-H) BrdUrd incorporation (black in B-H) marks cells in S phase. Cell-cycle arrest in the ZNC (wild type shown in B) is inhibited when a dominant-negative form of dTCF (dTCFΔN) is expressed in the ZNC with the C96>Gal4 wing-margin-specific driver (C). Overexpression of dE2f1 (D) or dMyc (E) with the C96>Gal4 driver promotes G1 progression in regions of the ZNC that are normally arrested in G1. Coexpression of Rbf-280 with dMyc (F) slightly inhibits the ability of dMyc to promote G1 progression in the ZNC. Overexpression of Dap and Rbf-280 with dMyc (G) or with dTCFΔN (H) promotes G1 arrest. Third-instar wing discs oriented anterior left and dorsal up are shown here and in all subsequent figures.

The mechanism by which Wg induces G1 arrest in the ZNC is not understood. Interestingly, Wg signaling inhibits expression of the growth inducer Drosophila myc (dmyc) in the ZNC (ref. 10; Fig. 2G). Myc is a transcription factor that heterodimerizes with Max; Myc-Max heterodimers promote transcription of genes with proximal E box consensus binding sites (11-13). dMyc is known to promote G1-S progression in Drosophila (10). However, the transcriptional targets that mediate dMyc's ability to promote G1 progression in flies have not yet been identified. Identification of such targets could lead to a better understanding of how Wg-mediated G1 arrest is obtained in the ZNC, where dMyc expression is normally inhibited.

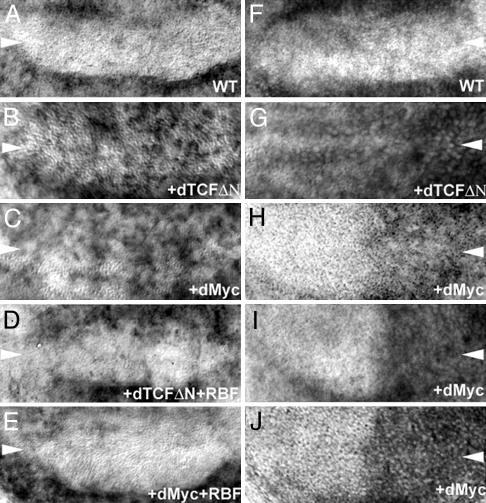

Fig. 2.

Regulation of gene expression in the ZNC. Expression of the dE2f1 target gene PCNA is normally inhibited in the ZNC (A). Expression of either dTCFΔN (B) or dMyc (C) with the C96>Gal4 driver induces ectopic PNCA expression. Using the C96>Gal4 driver to coexpress Rbf-280 with dTCFΔN (D) or dMyc (E) restores repression of PCNA expression. Expression of dmyc is normally inhibited by Wg in the ZNC (F). When Wg signaling is disrupted by expression of dTCFΔN with the C96>Gal4 driver, dmyc expression is no longer repressed (G). Expression of dMyc with the En>Gal4 driver (H-J), which drives gene expression in the posterior of the wing, induces higher Cyclin E (H), Cyclin D (I), and cdk4 (J) levels (compare to wild-type RNA levels in the anterior of each disk). Expression levels were analyzed through in situ hybridization.

The retinoblastoma (Rb) pathway, a key regulator of the G1-S phases of the cell cycle (14, 15), is a potential Wg target that could function to regulate the cell cycle in the ZNC. In its hypophosphorylated state, Rb proteins [such as Drosophila Retinoblastoma family (Rbf)] bind to and inhibit E2f, a heterodimer composed of an E2f and a DP subunit. E2f proteins, such as Drosophila E2f1 (dE2f1), regulate the transcription of a number of genes that function to promote S phase, such as DNA polymerase and Cyclin E. Binding of Rbf to dE2f1 inhibits the transcription activating function of dE2f1 and mediates G1 arrest. Rbf could therefore mediate the ability of Wg to promote G1 arrest in the ZNC. The role of Rbf in the ZNC, as well as the potential relationship between dMyc and the Rbf/E2f pathway, is examined here.

Materials and Methods

Fly Strains. Fly strains used in this study include: FRT18A; MKRS,Hs-Flp/TM6b (16); Rbf14 (17); UAS-dmyc42 (18); UAS-Rbf- 280 (19); UAS-dap (20); UAS-dTCFΔN1 (21); C96>Gal4, UAS-GFPNLSS65T (6, 22); and en>Gal4, UAS-GFPNLSS65T (23).

Generation of Clones. The FLP/FRT system (16) was used to generate Rbf-/- clones in larvae of the following genotype: Rbf14, FRT18A/FRT18A; MKRSHs-Flp/+. Heat shocks (38°C for 1 h) were given to generate FLP expression ≈48 h after the midpoint of the egg collection.

Immunohistochemistry and in Situ Hybridization. The following antibodies were used in this investigation: anti-BrdUrd mouse monoclonal (Becton Dickinson); FITC-conjugated anti-BrdUrd mouse monoclonal (Boehringer Mannheim); anti-Rbf (17); and anti-Digoxygenin mouse monoclonal (Roche Diagnostics). Secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch. Discs were removed from wandering third-instar larvae and fixed for 15-30 min in 4% paraformaldehyde. Antibody staining was performed generally according to the procedure described by Patel (24). In situ hybridization was performed by using a modified version of the Patel (25) protocol.

BrdUrd Incorporation. Third-instar larvae were dissected in M3 culture media (Sigma), and discs were transferred immediately to M3 containing 0.3 mg/ml BrdUrd (U.S. Biologicals, Swampscott, MA). The discs were incubated in BrdUrd for 60 ± 10 min, rinsed with M3 for 15 min, rinsed with PBS for 15 min, and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. After fixation, discs were rinsed with PBS plus 0.1% Triton X-100 (PT) and then treated with 4 M HCl for 30 min. After the acid treatment, discs were rinsed, and primary antibody was applied.

Flow Cytometry. Wing discs expressing UAS-transgenes under C96>Gal4; UAS-GFP (22) control were dissociated as described (10, 23). GFP expression marked cells under control of C96>Gal4. Analysis of cell-cycle phasing and cell size [by forward scatter (FSC)] was carried out by using a Beckman Coulter Ultra Hypersort. Seventy wing discs were examined per experiment. Data analysis was done with cellquest (BD Biosciences) software. Cell-cycle phasing was estimated by gating the G1 and G2 peaks in cellquest. Gates were imposed on the G1 and G2 peaks in controls and then used to estimate the fraction of experimental cells in each phase of the cell cycle. Values reported in Fig. 4 represent a typical experiment. Cell size was measured by examining FSC distributions as described (23). Mean FSC values of experimental cells marked with GFP were normalized to the mean FSC value of control cells expressing GFP alone.

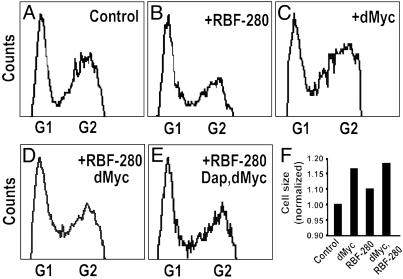

Fig. 4.

dMyc can promote cell-cycle progression and growth in the wing margin. (A-E) Cell-cycle phasing. The indicated genes were expressed with the C96>Gal4 driver and marked by coexpression of GFP. GFP-expressing ZNC cells were analyzed through fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Estimated percentages of cells in each phase of the cell cycle are as follows. Control: 35.8% G1, 8.8% S, 55.4% G2; +Rbf-280: 39.7% G1, 8.7% S, 51.6% G2; +dMyc: 28.6% G1, 10.3% S, 61.1% G2; +Rbf-280, dMyc: 35.1% G1, 10.3% S, 54.6% G2; +Rbf-280, dMyc, Dap: 33.9% G1, 7.1% S, 59.0% G2. dMyc promotes G1-S phase progression; Rbf-280 and Dap block this progression. (F) Cell size. GFP again was used to mark ZNC cells of the indicated genotypes. FSC distributions of GFP-positive experimental cells/GFP-positive control cells are shown. Expression of dMyc with C96>Gal4 increases cell size, but coexpression of Rbf-280 with dMyc or Rbf-280 plus Dap plus dMyc (data not shown) does not block induction of growth by dMyc.

Results

Rbf Is Required for G1 Arrest in the ZNC. Cells in the posterior and anterior central region of the ZNC arrest in G1 during the third instar, as illustrated through their failure to incorporate BrdUrd (ref. 6; Fig. 1B). Wg is required for this G1 arrest, as well as for the G2 arrest of a subset of cells in the anterior ZNC (ref. 6; Fig. 1A). In the ZNC of wgts mutants, or in presumptive wing margins in which dTCFΔN, a dominant-negative form of the Wg-transducer Drosophila TCF (21), has been expressed, cells that normally undergo cell-cycle arrest fail to do so (ref. 6; Fig. 1C). Although it is known that Wg induces G2 arrest in the anterior dorsal and ventral domains of the ZNC through inhibition of string (6), the mechanism by which Wg induces G1 arrest in the anterior central and posterior regions of the ZNC (Fig. 1A)is not well understood.

Inhibition of dE2f1 target genes such as RNR-2 (6) and PCNA (Fig. 2A) in the wild-type ZNC suggests that Wg signaling might function to inhibit the transcription factor dE2f1, which is expressed in the ZNC (data not shown). To study this, dTCFΔN was expressed ectopically by using the C96>Gal4 (22) driver, which is specific to the presumptive wing margin; previous studies show that expression of dTCFΔN in the ZNC mimics results obtained with the wgts mutant (6). Expression of dTCFΔN leads to ectopic PCNA expression in the ZNC (Fig. 2B), suggesting that loss of Wg signaling results in activation of dE2f1. When Rbf-280, a constitutively active form of Rbf (19), is coexpressed with dTCFΔN in the ZNC, the normal inhibition of PCNA expression is restored (Fig. 2D). These observations suggest that Wg signaling might promote G1 arrest in the ZNC by activating Rbf, which would then inhibit dE2f1.

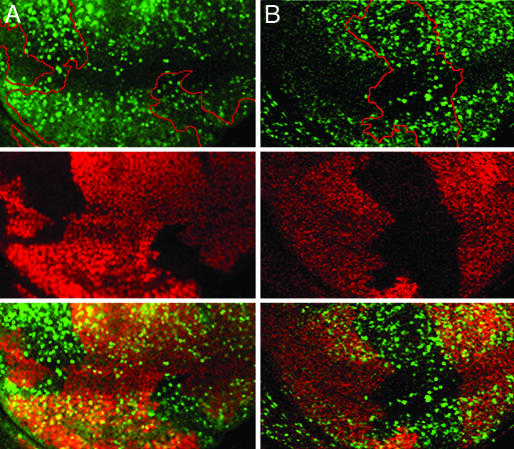

To examine whether Rbf is required to induce cell-cycle arrest in the ZNC, the effect of Rbf loss on ZNC G1 arrest was investigated. BrdUrd incorporation was examined in clones of cells that lack a functional copy of Rbf. Cells lacking Rbf fail to arrest in G1 in both the anterior central and posterior regions of the ZNC (Fig. 3). Overexpression of dE2f1 in these G1 arrested regions results in a similar loss of arrest (Fig. 1D). These data indicate that Rbf is, in fact, required for G1 arrest in the ZNC.

Fig. 3.

Rbf is required for G1 arrest in the ZNC. Loss of Rbf (indicated by loss of Rbf staining, red, in the circled Rbf-/- clones shown in Middle) results in S-phase entry in regions of the ZNC that are normally arrested in G1 (BrdUrd in green, Top; overlay shown in the Bottom). Two clones are visible in A, and a single clone is visible in B.

Repression of dmyc Expression by Wg Is Required for Rbf Function in the ZNC. The mechanism by which Wg promotes Rbf function in the ZNC was examined. Expression of dTCFΔN in the wing margin has no impact on levels of Rbf (data not shown), indicating that Wg does not regulate Rbf expression. However, previous studies have shown that Wg signaling does function to inhibit expression of dmyc in the presumptive wing margin (ref 10; Fig. 2G). When Wg signaling is inhibited through expression of dTCFΔN, dmyc is expressed ectopically in the ZNC (10). Expression of dMyc, like overexpression of dE2f1 (Fig. 1D) or loss of Rbf (Fig. 3), is sufficient to prevent the block to G1-S phase transition in the ZNC, as evidenced through BrdUrd incorporation (Fig. 1E) and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Fig. 4C) experiments (10). These observations suggest that inhibition of dMyc expression in the ZNC is critical for Rbf-mediated G1 arrest.

To examine whether dMyc activates the E2f pathway in the ZNC, the effect of dMyc expression on dE2f1 target gene transcription was examined. When dMyc is expressed in the presumptive wing margin with C96>Gal4, PCNA expression is induced (Fig. 2C). Thus, ectopic expression of dMyc, like inhibition of Wg signaling, activates the Rbf/E2f pathway in the ZNC. These observations indicate that during normal development of the wing margin, repression of dmyc expression by Wg is required for Rbf-mediated G1 arrest.

dMyc Can Inactivate Rbf Through Induction of G1-S Cyclin and Cdk4 Expression in the ZNC. To better understand why repression of dMyc expression by Wg is required for Rbf-mediated G1 arrest in the ZNC, the mechanism by which dMyc activates dE2f1 was examined in more detail. Cyclins D and E, inhibitors of Rbf (14), both are expressed at low levels in the ZNC (see anterior portion of presumptive wing margins in Fig. 2 H and I). The effects of dMyc on expression of these G1 cyclins were examined. When dMyc is expressed by using the En>Gal4 driver (which promotes UAS-transgene expression in the posterior of the wing), high levels of Cyclin E mRNA (Fig. 2H) expression are induced in the posterior of the wing disk, including the ZNC. Similarly, expression of dMyc promotes ectopic expression of Cyclin D mRNA in the presumptive wing margin (Fig. 2I). Higher levels of Cyclin E and D proteins also were noted in the ZNC when dMyc was expressed with either the En>Gal4 or C96>Gal4 drivers (data not shown). Furthermore, dMyc can induce expression of Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (cdk4) mRNA, Cyclin D's kinase partner (Fig. 2J). These observations suggest that the ability of dMyc to promote G1 progression in the ZNC (Fig. 1E) occurs through induction of cdk4, Cyclin D, and Cyclin E, known inhibitors of Rbf (14).

To test this hypothesis, constitutively active Rbf-280, which cannot be regulated by G1-S cyclins (19), was coexpressed with dMyc in the presumptive wing margin. Overexpression of the dE2f1 target gene PCNA is observed when dMyc is expressed ectopically in the ZNC (Fig. 2C). This induction of PCNA expression can be inhibited by coexpression of constitutively active Rbf-280 with dMyc (Fig. 2E). These studies suggest that when dMyc is expressed ectopically in the ZNC, cells express high levels of Cyclin D, Cyclin E, and Cdk4, which can inactivate Rbf, resulting in dE2f1-activated transcription.

Because coexpression of Rbf-280 with dMyc inhibits the ability of dMyc to induce PCNA expression, its ability to inhibit dMyc-promoted G1 progression was tested. Coexpression of Rbf-280 with dMyc does not completely restore G1 arrest in the ZNC (Fig. 1F). Similarly, coexpression of Rbf-280 with dTCFΔN does not completely restore G1 arrest in the ZNC (data not shown). The inability of Rbf-280 to completely block dMyc-promoted G1-S progression is not surprising, because Cyclin E appears to promote S phase in the presence of Rbf-280 (2). Thus, increased levels of Cyclin E that are still observed when dMyc plus Rbf-280 are coexpressed in the wing margin (data not shown; this is also true of Cyclin D levels) might be capable of inducing S phase independently of Rbf in the ZNC. To test this idea, Dacapo (Dap), the Drosophila P21/27 homolog and inhibitor of CyclinE/Cdk2 (20, 26), was coexpressed with dMyc. Although Dap alone cannot block dMyc-promoted G1 progression (data not shown), when Rbf-280 and Dap are coexpressed with dMyc in the ZNC, no ectopic S phases are observed (Figs. 1G and 4E). Furthermore, coexpression of Rbf-280 and Dap with dTCFΔN restores G1 arrest in the ZNC (Fig. 1H). These results suggest that inhibition of both Cyclin D/Cdk 4 activity (by Rbf-280) and Cyclin E/Cdk2 activity (by Dap and Rbf-280) are required to block dMyc promoted G1-S progression. Thus, during normal development, inhibition of dMyc expression in the ZNC is necessary to prevent accumulation of high levels of Cyclin D/Cdk4 and Cyclin E, which could prevent G1 arrest.

dMyc Promotes Growth Independently of the Rbf/E2f Pathway. Exclusion of dMyc expression from the ZNC is a prerequisite for the growth arrest of these cells (growth is defined here as an increase in cell mass and cell size). Overexpression of dMyc in the ZNC results in a visible increase in cell size, which also can be detected through FSC analysis (ref. 10; Fig. 4F). Recent studies indicate that overexpression of Rbf-280 inhibits Cyclin D/Cdk4-induced cell growth and proliferation in the wing disk (19). These results suggested that dMyc, which induces cell proliferation in part through inhibition of Rbf, also might induce growth by inhibiting Rbf. To test this hypothesis, Rbf-280 was coexpressed with dMyc, and cell size was evaluated. Visual inspection of cells coexpressing Rbf-280 plus dMyc indicates that dMyc can still induce cellular growth in the presence of Rbf-280 (data not shown). This observation was confirmed with FSC analysis. The average size of cells expressing dMyc is higher than that of control cells (ref. 10; Fig. 4F), and this size is not reduced when dMyc plus Rbf-280 are coexpressed (Fig. 4F) or when Rbf-280 plus Dap are expressed in conjunction with dMyc (data not shown). These data suggest that dMyc induces cellular growth independently of the Rbf/E2f pathway.

Discussion

Rbf-Induced Cell-Cycle Arrest in the ZNC. This investigation examines the mechanism by which Wg signaling promotes G1 arrest in the presumptive Drosophila wing margin. It was postulated that Rbf might mediate the ability of Wg to induce G1 arrest, as loss of Wg signaling promotes expression of dE2f1 target genes (Fig. 2B). Overexpression of Rbf can block this induction of dE2f1 target gene expression (Fig. 2D). Strikingly, loss of Rbf in the ZNC prevents G1 arrest, as evidenced by ectopic BrdUrd incorporation in Rbf mutant clones (Fig. 3). This requirement for Rbf in the ZNC is notable. Surprisingly few developing fly tissues display such an absolute requirement for Rbf to promote G1 arrest. To date, Rbf has been shown to be required to limit DNA replication in the embryo (17) and in the ovary (27). However, in many tissues, loss of Rbf does not result in ectopic S phase (W.D., unpublished observation); a likely explanation for this finding is that in other developing tissues, Rbf may function as one of several redundant mechanisms that function to promote G1 arrest. Such redundancy would help to ensure that the cell cycle is regulated tightly during development.

Interactions Between Rbf/E2f and dMyc in Drosophila. In an attempt to better understand the mechanism by which Wg promotes Rbf function, this investigation uncovered interactions between dMyc and components of the Rbf/E2f pathway. Wg signaling normally inhibits dMyc expression in the ZNC (ref. 10; Fig. 2G). Ectopic expression of dMyc in the ZNC can induce expression of dE2f1 target genes (Fig. 2C), which can be blocked by the addition of Rbf-280 (Fig. 2E). Thus, overexpression of dMyc, which results from loss of Wg signaling in the ZNC, must somehow inactivate Rbf. These data indicate that inhibition of dMyc expression in the ZNC is critical for Rbf function.

The results presented in Fig. 2 H-J indicate why exclusion of dMyc from the ZNC is necessary for Rbf activity. Overexpression of dMyc leads to high levels of Cyclin E, Cyclin D, and Cdk4 transcripts. dMyc also regulates Cyclin E posttranscriptionally in Drosophila (28). G1-S Cyclins/Cdks function to phosphorylate and inhibit Rbf, suggesting that dMyc blocks Rbf activity through activation of G1-S Cyclins/Cdks. Thus, inhibition of dMyc by Wg helps to ensure that G1-S Cyclins/Cdks do not activate S phase. This idea is supported by the results shown in Fig. 1 G and H, which indicate that only a combination of both Dap and constitutively active Rbf (that cannot be regulated by Cyclins/Cdks) can restore G1 arrest when Wg signaling is blocked or when dMyc is expressed. These results are summarized in Fig. 5. These data suggest that either Cyclin D or Cyclin E activity can mediate the ability of dMyc to promote S phase in the ZNC. Coexpressing Dap alone with dMyc, which would block only Cyclin E/Cdk2 activity, does not restore G1 arrest (data not shown). Furthermore, overexpression of dMyc in a cdk4 mutant background still results in ectopic S phases (data not shown), suggesting that Cyclin E/Cdk2 also are sufficient to mediate dMyc's ability to promote G1 progression. Thus, either Cyclin D/Cdk4 or Cyclin E/Cdk2 is sufficient to mediate the ability of dMyc to promote G1 progression. The ability of Wg to inhibit dMyc expression is thus critical for RBF activation and G1 arrest in the ZNC. Still, it is possible that Wg promotes G1 arrest through other mechanisms that have not yet been uncovered. Our observation that overexpression of dTCFΔN with C96>Gal4 can promote S phase even in a dmyc mutant background (data not shown) supports this idea.

Fig. 5.

Model for the induction of G1 arrest by Wg in the ZNC. The genetic interactions for induction of G2 arrest by Wg were described previously (6). This study indicates that induction of G1 arrest by Rbf depends on the inhibition of dMyc expression by Wg.

It is likely that dMyc/dMax directly up-regulate transcription of Cyclin D and cdk4 in Drosophila. Myc/Max heterodimers regulate transcription by binding to various consensus sequences, such as the E box (11-13, 29). Previous studies indicated that cMyc induces Cyclin D2 expression in mice by binding to two consensus E boxes in the Cyclin D2 promoter (30). cdk4 also was identified as a transcriptional target of c-Myc (31). Furthermore, Orian et al. (29), who recently used the DamID method to carry out global genomic mapping of the Drosophila Myc, Max, and Mad/Mnt proteins, have suggested that cdk4 is a transcriptional target of dMyc and Cyclin D is a transcriptional target of dMax. Although future studies should analyze the Drosophila Cyclin D and Cdk 4 regulatory regions in more detail, these results suggest that the observed ability of dMyc to induce Cyclin D and Cdk4 expression in the ZNC most likely occurs through transcriptional regulation of these proteins by dMyc/dMax. In contrast, Cyclin E was not identified as a target of dMyc or dMax (29). It is more likely that the ability of dMyc to induce growth in the wing (see below) indirectly leads to increased Cyclin E transcript levels.

dMyc Regulates Growth Independently of the Rbf Pathway. Recent studies indicate that both dMyc (10) and Rbf (19) can regulate cellular growth in the Drosophila wing. dMyc induces cellular growth, whereas Rbf inhibits cellular growth and proliferation. dMyc can promote cellular growth in the presence of constitutively active Rbf (Fig. 4F), suggesting that dMyc can induce growth independently of the Rbf/E2f pathway. Such results are consistent with previous studies that indicate that Ras, which can induce growth by increasing levels of dMyc protein (28), also is capable of inducing growth in the presence of Rbf (19). It is likely that dMyc regulates growth through induction of genes encoding regulators of protein synthesis, such as ribosomal proteins and the DEAD-box helicase Pitchoune, as well as other proteins that regulate cellular metabolism (18, 29).

Activation and Repression of Cell Proliferation by Wnt Signaling. Wnt signaling is generally associated with the stimulation of cell proliferation during development and in tumor cells (7, 8). However, in the ZNC, Wnt/Wg signaling actually promotes cell-cycle arrest (6). Ironically, in the ZNC, Wg signaling suppresses expression of dmyc (10); however, a cMyc reporter was found to be directly up-regulated by Tcf4 in a colon carcinoma cell line (32). Thus, Wg appears to be able to up-regulate Myc expression in some tissues and to repress it in others.

The ability of Wg signaling to either activate or repress the same target gene in different situations has been observed in other cases. For example, in the developing Drosophila midgut, low levels of Wg signaling, in conjunction with Dpp, stimulate expression of Ubx and lab; high levels of Wg signaling result in the repression of Ubx and lab by means of the transcriptional repressor Teashirt (33, 34). Thus, expression of Wnt target genes can be turned on or off in response to the modulation of Wg levels as well as by the presence or absence of the various proteins that can regulate transcription in conjunction with, or in response to, Wg signaling. Such flexibility is advantageous to a developing organism.

Developmental Morphogens: Patterning, Differentiation, and Cell Cycle Regulation. Wg signaling can be modulated to affect expression of the same target gene differently in various situations. Moreover, Wg signaling can be modulated to promote or inhibit the different, somewhat conflicting cellular processes of patterning, growth, proliferation, and differentiation. The same is true for Hh signaling, which also regulates all of these cellular processes (2). Thus, it seems, at least in the case of Hh and Wg, that one signaling molecule can regulate many different types of cellular and developmental events. In order for various cellular programs to be implemented and coordinated during development, the way that a particular cell type responds to Wg or Hh signaling at any given time must be tightly regulated. The delicate balance between various processes that can occur in response to Hh or Wg signaling is likely maintained through tight control of the temporal and spatial expression patterns of Hh and Wnt targets and the molecules that regulate them.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Du lab and the Ben May Institute for helpful discussions and comments. We also thank the Bloomington Stock Center (Indiana University, Bloomington) for fly stocks, A. Sanders for technical help, and T. Jessel and I. Schieren for fluorescence-activated cell sorter use and assistance. This work was supported by an Albion College Faculty Development grant (to M.D.-S.) and a National Institutes of Health grant (to W.D.). L.A.J. is supported by the V Foundation for Cancer Research and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD42770. W.D. is a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar. L.A.J. is a V Foundation Scholar.

Abbreviations: Wg, Wingless; Rb, retinoblastoma; Rbf, Rb family; Hh, Hedgehog; ZNC, zone of nonproliferating cells; dmyc, Drosophila myc; FSC, forward scatter; cdk, cyclin-dependent kinase; Dap, Dacapo.

References

- 1.Skaer, H. (1998) Trends Genet. 14, 337-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duman-Scheel, M., Weng, L., Xin, S. & Du, W. (2002) Nature 417, 299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cubas, P., de Celis, J. F., Campuzano, S. & Modolell, J. (1991) Genes Dev. 5, 996-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skeath, J. B. & Carroll, S. B. (1991) Genes Dev. 5, 984-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Brochta, D. A. & Bryant, P. J. (1985) Nature 313, 138-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston, L. A. & Edgar, B. A. (1998) Nature 394, 82-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serrano, N. & O'Farrell, P. H. (1997) Curr. Biol. 7, R186-R195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taipale, J. & Beachy, P. A. (2001) Nature 411, 349-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston, L. A. & Sanders, A. L. (2003) Nat. Cell. Biol. 5, 827-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston, L. A., Prober, D. A., Edgar, B. A., Eisenman, R. N. & Gallant, P. (1999) Cell 98, 779-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackwood, E. M., Kretzner, L. & Eisenman, R. N. (1992) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2, 227-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amati, B. & Land, H. (1994) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 4, 102-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henriksson, M. & Luscher, B. (1996) Adv. Cancer Res. 68, 109-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinberg, R. A. (1995) Cell 81, 323-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyson, N. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 2245-2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu, T. & Rubin, G. M. (1993) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 117, 1223-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du, W. & Dyson, N. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 916-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaffran, S., Chartier, A., Gallant, P., Astier, M., Arquier, N., Doherty, D., Gratecos, D. & Semeriva, M. (1998) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 125, 3571-3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xin, S., Weng, L., Xu, J. & Du, W. (2002) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 129, 1345-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lane, M. E., Sauer, K., Wallace, K., Jan, Y. N., Lehner, C. F. & Vaessin, H. (1996) Cell 87, 1225-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van de Wetering, M., Cavallo, R., Dooijes, D., van Beest, M., van Es, J., Loureiro, J., Ypma, A., Hursh, D., Jones, T., Bejsovec, A., et al. (1997) Cell 88, 789-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gustafson, K. & Boulianne, G. L. (1996) Genome 39, 174-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neufeld, T. P., de la Cruz, A. F., Johnston, L. A. & Edgar, B. A. (1998) Cell 93, 1183-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel, N. H. (1994) Methods Cell Biol. 44, 445-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel, N. (1996) In Situ Hybridization to Whole Mount Drosophila Embryos (Wiley-Liss, New York).

- 26.de Nooij, J. C., Letendre, M. A. & Hariharan, I. K. (1996) Cell 87, 1237-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bosco, G., Du, W. & Orr-Weaver, T. L. (2001) Nat. Cell. Biol. 3, 289-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prober, D. A. & Edgar, B. A. (2000) Cell 100, 435-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orian, A., van Steensel, B., Delrow, J., Bussemaker, H. J., Li, L., Sawado, T., Williams, E., Loo, L. W., Cowley, S. M., Yost, C., et al. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 1101-1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouchard, C., Thieke, K., Maier, A., Saffrich, R., Hanley-Hyde, J., Ansorge, W., Reed, S., Sicinski, P., Bartek, J. & Eilers, M. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 5321-5333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hermeking, H., Rago, C., Schuhmacher, M., Li, Q., Barrett, J. F., Obaya, A. J., O'Connell, B. C., Mateyak, M. K., Tam, W., Kohlhuber, F., et al. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 2229-2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He, T. C., Sparks, A. B., Rago, C., Hermeking, H., Zawel, L., da Costa, L. T., Morin, P. J., Vogelstein, B. & Kinzler, K. W. (1998) Science 281, 1509-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu, X., Riese, J., Eresh, S. & Bienz, M. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 7021-7032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waltzer, L., Vandel, L. & Bienz, M. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 137-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]