Abstract

Adult Treatment Panel (ATP), an expert panel to supervise cholesterol management was set up under the aegis of National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) in 1985. Since then NCEP-ATP has been revising and framing guidelines to enable clinician to deliver better treatment to cardiovascular patients and to educate general people. As a result, considerable reduction in cardiovascular related deaths has been observed in recent times. All three ATP guidelines viz. ATP-I, ATP-II and ATP-III have targeted low density lipoprotein as their primary goal. The ATP-III guideline was updated in the light of evidences from 5-major clinical trials and was released in 2004. It added therapeutic lifestyle changes, concept of risk equivalents, Framingham CHD-risk score non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C) as secondary target and gave strong emphasis on metabolic risk factors. The earlier treat-to-target paradigm faced fierce criticism from clinicians across the globe because of insufficient proof of safety and benefits of treating patients with respect to an individual's low density lipoprotein (LDL) level. Further, demonstration of non-HDL-C and total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio as strong predictors of overall cardiovascular risk foresees new guidelines. A tailored-treatment approach was suggested instead of LDL-C target based treatment approach which was soundly based on direct clinical trials evidences and proposes treatment based on individual's overall 5- to 10-year cardiovascular risk irrespective of LDL-C level, leading to lower number of people on high dose/s of statins. Recent report of the Cholesterol Treatment Trialist's Collaborators meta-analysis strongly supported primary prevention of LDL with statins in low risk individuals and showed that its benefits completely outweighed its known hazards. Markers other than LDL-C like apolipoprotein B, non-HDL-C and total cholesterol/HDL-C ratio would take precedence in the risk assessment and strong emphasis would be given on tailored-treatment approach in the upcoming ATP-IV guideline.

Keywords: Adult treatment panel, coronary heart disease, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

INTRODUCTION

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is one of the most prevailing causes of morbidity and mortality in the developed countries. There are several modifiable risk factors, including high blood cholesterol, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, obesity and psychosocial factors which play a crucial role in development and progression of cardiovascular disease. High blood cholesterol has been considered as one of the most important modifiable risk factor associated with CHD.[1] In 1984, the Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial provided definitive evidence of CHD risk reduction with lowering of high blood cholesterol.[2]

Cholesterol, an integral component of cell membranes and a precursor for bile acids and steroid hormones, travels in the blood with the help of proteins called lipoproteins. There are three major classes of lipoproteins: Low density lipoprotein (LDL), high density lipoprotein (HDL), and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), which typically constitutes 60-70%, 20-30%, and l0-15% of the total cholesterol, respectively. As LDL-C binds to maximal concentration of cholesterol, it can be considered as a mirror image of total cholesterol concentration in blood. Hence LDL-C has been considered as the primary target of cholesterol lowering efforts. It has been observed that statins, the cholesterol-lowering drugs, dramatically reduce heart attacks, CHD deaths, and overall mortality rates with lowering of LDL-C.[3]

The present review strives to throw light on salient features of NCEP-ATP guidelines that had evolved with continual advances in clinical research and cholesterol management guidelines.

Search strategy used

We identified electronic databases, mainly MEDLINE, HighWire, Cochrane and Google Scholar for searching articles from 1980 through February, 2012 by using keywords “Cholesterol Management Guidelines,”, “National Cholesterol Education Program”, “Adult Treatment Panel”. In MEDLINE, we have used “(cholesterol) AND (Adult treatment panel) AND (Guidelines)” as the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms.

NATIONAL CHOLESTEROL EDUCATION PROGRAM: GUIDELINES FOR TREATMENT OF HYPERLIPIDEMIA

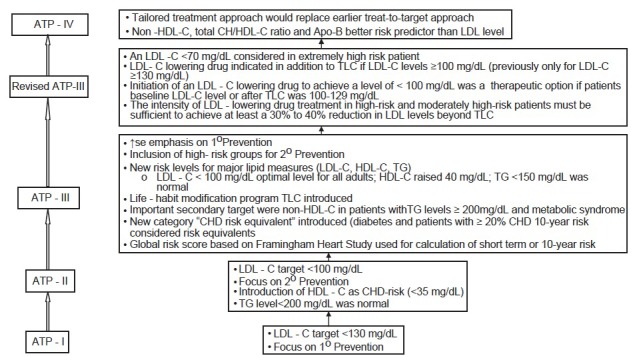

In 1985, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institute of Health constituted NCEP with an objective to educate general public and medical community about the need to identify and treat high blood cholesterol in reducing CHD risk.[4] Therefore, the adult treatment panel (ATP), a panel represented by experts from major medical and health professional associations, voluntary health organizations, community programs, and governmental agencies was constituted. The aim of this panel was to develop guidelines for detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults. The ATP guidelines are currently the most accepted reference guideline for clinical management of high blood cholesterol. With continual clinical advances in the science of cholesterol management, these guidelines are periodically updated. The first ATP guideline i.e., ATP-I was published in the year 1988 which outlined a strategy for primary prevention of CHD in individuals with high LDL-C (>160 mg/dL) or with borderline-high LDL-C (130-159 mg/dL) including more than two risk factors.[5,6] In 1993, ATP-II, the second ATP guideline, supported the approach of ATP-I and added a new feature of intensive management of LDL-C in patients with established CHD (secondary prevention) and fixed a new, lower LDL-C goal of <100 mg/dL in CHD patients.[7,8] Six years later, in 2001, the third ATP guideline, ATP-III[6,9] was developed on the foundation of previous ATP guidelines and represented an update of recommendations for clinical management of high blood cholesterol and related abnormalities and at the same time maintaining continuity with ATP-I and ATP-II guidelines. The prominent features of ATP-III included consideration of LDL-C <100 mg/dL as optimal level, introduction of Framingham risk score (10-year CHD risk) to calculate treatment intensity and life-habit modification program termed “therapeutic lifestyle modification” (TLC). Other important secondary targets in ATP-III guidelines were non-HDL-C in patients with a triglycerides (TG) values ≥200 mg/dL and metabolic syndrome. Since ATP-III, five major clinical trials involving statin have been published. The updated ATP-III was based on reviews of these five clinical trials and was released in 2004.[10,11] These trials brought into light several startling facts that critically influenced cardiovascular treatment and addressed important issues that were not taken care of by ATP-III. The most noticeable change in updated ATP III guideline was the LDL-C goal of <70 mg/dL which was considered as a reasonable clinical strategy for patients at extremely high risk. This gradual evolution of NCEP guidelines in the form of ATP guidelines (ATP-I till ATP-III) has posed a tremendous impact on cholesterol management with regard to the lives of cardiac patients.[12] A new updated ATP guideline, ATP-IV is expected sometimes in July/August 2012 and most likely would have its recommendations in the light of sound clinical evidences till date. Previous treat-to-target paradigm in ATP-III which was LDL target based approach might be replaced with new more evidence based tailored treatment in ATP-IV guideline [Figure 1].[13]

Figure 1.

Evolution of adult treatment panel: ATP-I through updated ATP-III ATP: Adult treatment panel, ATP III’: Updated ATP-III, CHD: Coronary heart disease, HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein, LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein, TLC: Therapeutic lifestyle changes, TG: Triglycerides, 1° Prevention: Primary prevention, 2° Prevention: Secondary prevention

Adult treatment panel-I

Adult Treatment Panel-I was a high cholesterol management guideline in adults aged more than 20 years. It greatly helped in identifying patients who required lipoprotein analysis for cholesterol lowering therapy and helped in evaluating them with respect to other CHD risk factors. It also emphasized on primary prevention of CHD and recommended an LDL-C goal of 130 mg/dL. Patients with CHD having either high LDL-C (>160 mg/dL and above) or borderline-high (130-150 mg/dL) levels and multiple risk factors were considered for primary prevention.[5,6] ATP-I guideline stressed on the dietary therapy, specified LDL-C levels at which dietary therapy must be initiated and the nature of dietary changes. In addition, recommended drug therapy if LDL-C level was above their specified level even after 6 months of intensive dietary therapy. Based on the level of cholesterol in blood, three categories were formulated: (1) Desirable level-cholesterol <200 mg/dL; (2) Borderline-high level-cholesterol at 200-239 mg/dL; and (3) High level-cholesterol >240 mg/dL.

Adult treatment panel-II

Adult treatment panel-II was based on observational epidemiological review, lipoprotein metabolism, animal studies, and early clinical trials.[7,8] Pooling of data from early clinical trials revealed a definite trend towards reduced total mortality in patients with CHD but no clinical trial or meta-analysis showed reduction in total mortality in the primary prevention patients.[14] ATP-II recommended a cautious use of lipid lowering agents in primary prevention of CHD since benefits from pharmacological treatment of lower risk patients would diminish by increased relative risks and cost of the therapy. Further, at nascent stages of ATP-II publication several studies pertaining to safety of statins yield an inconclusive data. Hence this guideline preferred nicotinic acid and bile acid sequestrates over statins in several conditions.[7,8] According to ATP-II guideline, CHD risk status of the patient was used as a guide to the intensity of therapy and categorized patients into one of the 3 groups based on known atherosclerotic disease, multiple CHD risk factors and isolated hypercholesterolemia without other risk factors. For primary prevention, the target LDL-C were <160 mg/dL with <2 CHD risk factors; target LDL-C <130 mg/dL with ≥2 risk factors; and LDL-C <100 mg/dL was considered for secondary prevention of patients.[15] Various studies have considered HDL-C as an important and independent contributor to CHD risk.[4,16,17] ATP-II guideline considered HDL-C levels in therapeutic decision making and was added in initial patient screening along with total cholesterol level. HDL-C <35 mg/dL was recognized as a major risk factor and HDL-C >60 mg/dL was considered as a protector of CHD risk. ATP-II stressed on delaying the use of hypolipidaemic agents in young adults and preferred cholesterol lowering diets and exercise mostly in males aged <35 years, including premenopausal women. It also indicated hypolipidaemic agents for patients with LDL-C >220 mg/dL or with multiple CHD risk factors but in very young patients it usually preferred resins.[18] Even in elderly patients, caution must be taken while using cholesterol lowering medication in primary and secondary CHD prevention cases since risks of adverse effects may outweigh the likelihood of drug benefits. By the time ATP-II guideline was published, no clinical trials evaluated the effects and means of lowering TG in patient with severe hypertriglyceridemia which was once regarded as an additive risk factor for CHD. Therefore, ATP-II did not specify any goal for TG lowering.[19] In patients with diabetes, ATP-II recommended similar treatment goal to that of the established CHD cases due to high occurrence of CHD events in type 2 diabetics. Hence, ATP-II considered type 2 diabetics without known vascular disease as an additive CHD risk factor in absence of any plausible clinical trial data and recommended treatment with bile acid sequestrates or statins generally in combination with fibric acids in diabetic patients. Later, American Diabetes Association (ADA) clinical practice recommended initiation of hypolipidaemic therapy in all patients with type 2 diabetes and LDL-C >130 mg/dL. In addition, also fixed LDL-C goal of <100 mg/dL for secondary CHD prevention.[20]

Adult treatment panel-III

The adult treatment panel-III, comparatively a recent ATP guideline was supported by evidence from continuing research and widespread consensus on the benefits of aggressive treatment of high blood cholesterol.[6] The ATP-III guideline provided evidence based strategies for identifying and reducing CHD risk.[21] The most distinctive feature of ATP-III that differentiated it from ATP I and ATP II guideline was introduction of the concept of risk and risk assessment as the first step in risk management strategies, considering both long-term (lifetime) and short-term (10-year) risks. According to this guideline, it was important to identify a lifetime risk in people who were relatively at low short-term risk but had a single major-risk factor. This helped to identify apparently healthy individuals even with a single aberrant risk factor. It also emphasized on exhaustive risk lowering strategies (especially drug therapies) in patients with higher short-term risk while exhaustive TLC was considered for patients with higher lifetime risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD).[22]

As per ATP-III guideline, the intensity of risk reduction intervention/s must be matched to an individual's absolute risk as a fundamental principle to prevention.[4] Other remarkable insertion in the guideline was an introduction of the concept of CHD risk-equivalents, multiple-risk factors and expansion of the concept of primary prevention which was one of the feature of ATP-I guideline. In comparison to ATP-II, ATP-III guideline added a new intensity to LDL-C lowering in patients with more than two CHD risk factors.

ATP-III guideline involved the following 9 steps: [23]

Step I: Determination of lipoprotein levels where complete lipoprotein profile was obtained after 9-12hrs fasting.

Step II: Identification of the presence of atherosclerotic disease that heightens the risk for CHD events (CHD risk equivalent) e.g. clinical CHD, symptomatic carotid artery disease, peripheral arterial disease and abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Step III: Determination of the presence of major risk factors, excluding LDL. The major risk factors modifying LDL-C goals included cigarette smoking, blood pressure (≥140/90 mmHg), low HDL-C (<40 mg/dL), family history of premature CHD and age (men ≥45 years; women ≥55 years). HDL-C ≥60 mg/dL was counted as a “negative” risk factor as its presence was assumed to remove one risk factor from the total count of risk factors.

Step IV: Presence of >2 risk factors (excluding LDL) without CHD or CHD-risk equivalents necessitated an assessment of short-term (10 year) CHD risk. Based on 10-year risk, 3 risk categories were developed: (1) CHD risk equivalent (10 year risk >20%); (2) more than 2 risk factors (10 year risk of 10-20%); and (3) 0-1 risk factor (10 year risk < 10%).

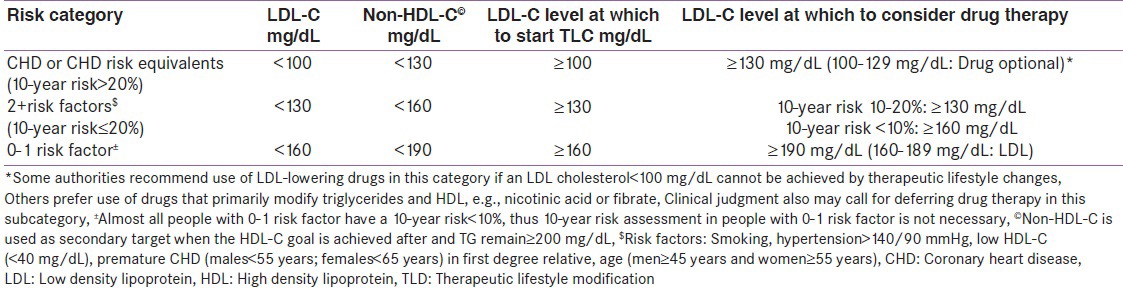

Step V: These 3 risk categories helps to establish LDL-C goal of therapy, determine a need for TLC and the level for drug consideration. Table 1 summarizes LDL-C goals and cut-points for TLC and drug therapies in different risk categories.

Table 1.

LDL-c and non-HDL-c goals, and cut points for TLC in different risk categories in adult treatment panel-III guideline

Step VI: TLC must be initiated if LDL was above the goal level [Table 1]. TLC includes diet management (saturated fat <7% of calories, cholesterol <200 mg/day, increased use of viscous [soluble] fiber [10-25 g/day] and plant stanols/sterols [2 g/day] for enhancing LDL reduction), weight management and increased physical activity.

Step VII: Drug therapy must be initiated if the level of LDL exceeds extremely above the target goal [Table 1]. For CHD and CHD equivalents, drug along with TLC was recommended and for other risk categories, addition of drug to TLC after three months was recommended.

Step VIII: Identification of metabolic syndrome, and treat, if present, after three months of TLC. Treatment of metabolic syndrome included (1) treatment of underlying causes (overweight/obesity and physical activity) by intensive weight management and increased physical activity and (2) treatment of lipid/non-lipid risk factors, if persisted despite lifestyle therapies by treatment of hypertension, use of aspirin to reduce prothrombotic state in CHD patients and by treatment of elevated TG and/or low HDL (described in step IX).

Step IX: There are four levels of serum TG: <150 mg/dL (normal), 150-199 mg/dL (borderline high), 200-499 mg/dL (high) and ≥500 mg/dL (very high). Patients with elevated TG (levels ≥150 mg/dL) were treated to achieve the LDL goal. The treatment included intensification of weight management and increased physical activity. After achieving LDL goal, if the TG level was ≥200 mg/dL, then the secondary goal for non-HDL-C (total cholesterol – HDL-C) was set 30 mg/dL (fixed increment over LDL goal) higher than the LDL goal. If the level of TGs was 200-499 mg/dL even after achieving LDL goal, addition of drug was required to reach non-HDL goal. The drug may be a LDL-lowering drug which intensifies the therapy or add nicotinic acid/fibrates to further lower down the level of very low-density lipoprotein. If TG ≥500 mg/dL, the first step was to reduce TGs to prevent pancreatitis by (1) the use of very low fat diet (≤15% of calories from fat); (2) weight management and physical activity; and (3) use of fibrate or nicotinic acid. Once TG is below 500 mg/dL, the treatment was switched to LDL-lowering therapy. Patients with low HDL-C (<40 mg/dL) were first treated to reach the LDL goal followed by intensive weight management and increased physical activity. If these patients had TG as 200-499mg/dL, they were targeted to achieve non-HDL goal and if had TG <200 mg/dL in CHD/CHD equivalent then nicotinic acid or fibrates were considered.

Revised adult treatment panel-III

Adult treatment panel-III was revised and published in 2004.[10,11] The revised ATP-III guideline was based on the review of five statin trials conducted since the release of ATP-III.[24,25,26,27,28] These trials addressed issues that were not adequately addressed in previous statin trials and forecasted important implications for the management of patients with lipid disorders, particularly high-risk patients. Hence, there was a demand to revise treatment thresholds in ATP-III guideline. The revised ATP-III guideline offered options for further intensive cholesterol-lowering treatment for patients at high and moderately-high risk for a heart attack. It also emphasized on TLC which served as the cornerstone of treatment for lowering cholesterol levels. The salient features of revised ATP-III guideline are as follows:

For high-risk patients, LDL-C treatment goal was LDL <100 mg/dL but an LDL-C goal of <70 mg/dL was considered a therapeutic option for very high risk patients who had recent heart attacks, cardiovascular disease with diabetes, metabolic syndrome, or severe/poorly controlled risk factors.

If LDL-C ≥100 mg/dL in high-risk patients, LDL-C lowering drug along with TLC (formerly indicated for ≥130 mg/dL) was recommended.

If LDL-C <100 mg/dL in high-risk patients, initiation of LDL-C lowering drug to achieve LDL-C <70 mg/dL was a therapeutic option.

For moderately high-risk patients, LDL-C goal remains <130 mg/dL but LDL-C <100 mg/dL was considered a therapeutic option when baseline LDL-C or LDL-C after treatment was between 100-129 mg/dL and LDL-C lowering drugs were initiated to achieve LDL-C <100 mg/dL.

Advised that intensity of LDL-C lowering drug treatment in high-and moderately high-risk patients be sufficient to achieve a reduction in LDL-C levels of at least 30-40% beyond TLC.

Adult treatment panel-IV

Previous ATP guidelines targeted LDL-C as the primary target for treating patients of atherosclerotic vascular diseases, including CHD. However, few reports highlighted LDL to no longer serve as a plausible risk factor for determining patients at cardiovascular risk in comparison to non-HDL-C or total cholesterol/HDL ratio[29,30,31,32,33] reflecting its reduced use in cardiovascular risk assessment. In 2008, Glasziou et al. demonstrated that LDL-based guidelines lead to either under-treatment (by not recommending adequate statin therapy in high cardiovascular risk/low LDL-patients) or over-treatment of patients with CVD (by recommending statin treatment in low cardiovascular risk/high LDL patients).[34] This may be due to the fact that LDL target levels considered in ATP-III were mostly extrapolated from results of randomized clinical trials that were not directly tested, failing to identify patients who are more likely to be benefited from statin therapy. Hence, LDL target based approaches indirectly promoted treatments that were not safe and resulted in over-treatment of patients with low risk of cardiovascular outcomes. Therefore, it was assumed that markers other than LDL-C like non-HDL-C and Apo B have higher significance in cardiovascular risk management.

Previous clinical trials mostly used fixed doses of drugs instead of titrating its doses to goal strategies. Therefore, it was contended that additional trials must look for evidence in support of LDL-C goals for secondary prevention.[35]

Cholesterol treatment trialists’ (CTT) collaborators recently published the results after meta-analyses of data from 27 trials (n = 174,149). They firmly supported primary prevention of LDL with statins. Based on the baseline five-year risk of major vascular events, the participants were grouped into five categories (<5, ≥5 to <10, ≥10 to <20, ≥20 to <30 and ≥30%) and were treated with either no statin or low-intensity statin. In the lowest two-risk categories (<5 and ≥5 to <10%) almost equivalent reduction in major vascular events was observed when compared to high risk categories.[36] In people with five-year risk <10%, each 1 mmol/L decrement in LDL-C led to an absolute reduction in major vascular events of about 11 per 1000 over five years. Though statins are known to predispose risk of myopathy/rhabdomyolysis, stroke (ischaemic and haemorrhagic) and diabetes[37,38,39] but this meta-analyses indicated extremely higher benefits of statin therapy in terms of overall reduction in cardiovascular events than its known hazards.[37] Thus, this study strongly supported statins to be safe and effective for patients with five-year risk of major vascular events <10% and also emphasized that the present cardiovascular guidelines should be re-revised. Hence, the new upcoming guideline should evaluate any new medications for its effect on patient outcome before including it in the guidelines since they are the vital part of quality measures. Another recent article “three reasons to abandon LDL targets” was published by Krumholz and Hayward in 2012 where they anticipated the treat-to-target paradigm and supported an approach distinct from target-based approach.[13] This potentially served as a harbinger of new guidelines wherein treatment targets must be replaced with extensive tailored treatment approach. All these reports strongly suggested that the new guideline (ATP-IV) should consider 1) markers other than LDL; 2) primary prevention of LDL with statins as they are safe and effective in patients with five-year risk of major vascular events <10%; and 3) the use of treat-to-target approach rather than target-based approach in cardiovascular risk management.

In a recent 72nd American Diabetes Association conference held on 8-12th June 2012 in Philadelphia, USA, it was declared that ATP-IV cardiovascular guideline integrating blood pressure, cholesterol, obesity, lifestyle and risk assessment considerations would be slated for the first draft publication sometimes in July/August 2012. The ATP-IV component of the guideline would address following three critical areas: 1) Evidence supporting LDL-C for secondary prevention; 2) Primary prevention of LDL; and 3) Efficacy and safety of major cholesterol drugs. In addition, would also address following critical questions regarding lifestyle considerations for lipid-lowering: 1) Effects of dietary patterns and/or macronutrient composition on lipids and blood pressure compared with no treatment or other intervention underweight-stable conditions; 2) Dietary effects of sodium and potassium on coronary heart disease/CVD outcomes and risk factors, also under weight-stable conditions; and 3) Effects of physical activity on CVD risk factors, also under weight-stable conditions.

The ATP-IV guideline would be using markers like Apo B, non-HDL-C (non-LDL-C markers) and tailored-treatment approach (personalized or individualized care) in making therapeutic decisions. This tailored-treatment approach was based more directly on clinical trial evidence than treat-to-target paradigm and may potentially translate into better outcomes in terms of patient management, at the same time reduce harm and cost of the therapy incurred by over-treating low-risk/low benefit individuals.[40,41] In this approach, the intensity of statin therapy was based on an individual's overall five to 10-year cardiovascular risk irrespective of LDL level which saved approximately 100,000 more quality-adjusted life years per annum, leading to a lower number of patients on high statin dose/s. Furthermore, it showed unexpected high effectiveness or efficiency than treat-to-target approach that even 10 international lipid experts, who strongly supported an LDL-based approach were not able to provide any scientific rationale to use treat-to-target approach.[42] Summarizing, the new ATP-IV guideline would preferably use tailored-treatment approach and promise to align its recommendations with strong clinical evidence regarding cardiovascular risk and risk reduction with lipid lowering agents, especially the statins and would also help in minimizing over-and under-treatment and in promoting optimized treatment with statin therapy.

CONCLUSION

Since inception in 1985, NCEP recognized the value of accurate and precise lipid and lipoprotein testing for effective implementation of its mission to lower death and disability from CVD by reducing the percentage of patients with high blood cholesterol. ATP I to III guidelines recognized LDL-C as the primary target and recognized treating patients to LDL-C targets. But over time, LDL target based approaches indirectly promoted treatments that were not safe and resulted in over-treatment of patients with low risk of cardiovascular outcomes. Various studies supported statins to be safe and effective for patients with five-year risk of major vascular events <10% and supported novel “tailored-treatment approach distinct from target-based approach. This tailored approach was soundly based on direct clinical trials evidences and proposes treatment based on individual's overall five to 10-year cardiovascular risk irrespective of LDL-C level, leading to lower number of people on high dose/s of statins. Hence, markers other than LDL including tailored treatment approach may see horizon of a new emerging guideline in the form of ATP-IV.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Max Neeman International, New Delhi, was responsible for preparation of the review article.

Footnotes

Source of Support: AstraZeneca wrt to Medical Writing support

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Castelli WP, Anderson K, Wilson PW, Levy D. Lipids and risk of coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1992;2:23–8. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(92)90033-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cholesterol Education Program, Program description: The NCEP science base. [Last Accessed on 2012 Mar 9]. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/ncep/ncep_pd.htm .

- 3.Grundy SM. Statin trials and goals of cholesterol-lowering therapy. Circulation. 1998;97:1436–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.15.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warnick GR, Myers GL, Cooper GR, Rifai N. Impact of the third cholesterol report from the adult treatment panel of the national cholesterol education program on the clinical laboratory. Clin Chem. 2002;48:11–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. The Expert Panel. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:36–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Summary of the second report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel II) JAMA. 1993;269:3015–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ansell BJ, Watson KE, Fogelman AM. An evidence-based assessment of the NCEP Adult Treatment Panel II guidelines. National Cholesterol Education Program. JAMA. 1999;282:2051–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.21.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel. Executive summary of the (NCEP) on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB, Jr, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–39. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone NJ, Bilek S, Rosenbaum S. Recent National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III update: Adjustments and options. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:53E–9E. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conti CR. Evolution of NCEP guidelines: ATP1-ATPIII risk estimation for coronary heart disease in 2002. National Cholesterol Education Program. Clin Cardiol. 2002;25:89–90. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960250302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayward RA, Krumholz HM. Three reasons to abandon low-density lipoprotein targets: An open letter to the Adult Treatment Panel IV of the National Institutes of Health. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:2–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.964676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braunstein JB, Cheng A, Cohn G, Aggarwal M, Nass CM, Blumenthal RS. Lipid disorders: Justification of methods and goals of treatment. Chest. 2001;120:979–88. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.3.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood D, De Backer G, Faergeman O, Graham I, Mancia G, Pyörälä K. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Summary of recommendations of the Second Joint Task Force of European and other Societies on Coronary Prevention. J Hypertens. 1998;16:1407–14. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816100-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Assmann G, Gotto AM., Jr HDL cholesterol and protective factors in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;109:III8–14. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131512.50667.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruckert E. Epidemiology of low HDL-cholesterol: results of studies and surveys. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2006;8:F17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guidelines for using serum cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglyceride levels as screening tests for preventing coronary heart disease in adults. American College of Physicians. Part 1. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:515–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-5-199603010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stampfer MJ, Krauss RM, Ma J, Blanche PJ, Holl LG, Sacks FM, et al. A prospective study of triglyceride level, low-density lipoprotein particle diameter, and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1996;276:882–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Diabetes Association. Management of dyslipidemia in adults with diabetes (position statement) Diabetes Care. 1999;22:S56–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipsy RJ. Effective management of patients with dyslipidemia. Am J Manag Care. 2003;9:S39–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasternak RC. Report of the Adult Treatment Panel III: The 2001 National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines on the detection, evaluation and treatment of elevated cholesterol in adults. Cardiol Clin. 2003;21:393–8. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(03)00080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cholesterol Education program. ATP III guidelines at-a-glance quick desk reference. [Last Accessed on 2012 Mar 15]. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/cholesterol/atglance.pdf .

- 24.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:7–22. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, Bollen EL, Buckley BM, Cobbe SM, et al. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1623–30. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11600-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive patients randomized to pravastatin vs usual care: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT) JAMA. 2002;288:2998–3007. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sever PS, Dahlöf B, Poulter NR, Wedel H, Beevers G, Caulfield M, et al. Prevention of coronary and stroke events with atorvastatin in hypertensive patients who have average or lower-than-average cholesterol concentrations, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Lipid Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1149–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12948-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Rader DJ, Rouleau JL, Belder R, et al. Pravastatin or atorvastatin evaluation and infection therapy-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 22 investigators. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495–504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel IV) [Last Accessed on 2012 Mar 12]. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/cholesterol/atp4/index.htm .

- 30.Hayward RA, Hofer TP, Vijan S. Narrative review: Lack of evidence for recommended low-density lipoprotein treatment targets: A solvable problem. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:520–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-7-200610030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sniderman AD, Williams K, Contois JH, Monroe HM, McQueen MJ, deGraaf J, et al. A meta-analysis of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B as markers of cardiovascular risk. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:337–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.959247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson KM, Wilson PW, Odell PM, Kannel WB. An updated coronary risk profile. A statement for health professionals. Circulation. 1991;83:356–62. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.1.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ridker PM, Paynter NP, Rifai N, Gaziano JM, Cook NR. C-reactive protein and parental history improve global cardiovascular risk prediction: The Reynolds Risk Score for men. Circulation. 2008;118:2243–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.814251. 4p following 2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glasziou PP, Irwig L, Heritier S, Simes RJ, Tonkin A. Monitoring cholesterol levels: measurement error or true change? Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:656–61. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-9-200805060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. [Last Accessed on 2012 Jun 29]. Available from: http://www.acli.com/Events/Documents/Tue22812%20-%20Lipidology%20-%20Pamela%20Morris.pdf .

- 36.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, Keech A, Simes J, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: Meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;380:581–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60367-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armitage J. The safety of statins in clinical practice. Lancet. 2007;370:1781–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60716-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, Holland LE, Reith C, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: A meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, Welsh P, Buckley BM, de Craen AJ, et al. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet. 2010;375:735–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61965-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krumholz HM, Hayward RA. Shifting views on lipid lowering therapy. BMJ. 2010;341:c3531. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayward RA. All-or-nothing treatment targets make bad performance measures. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13:126–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayward RA, Krumholz HM, Zulman DM, Timbie JW, Vijan S. Optimizing statin treatment for primary prevention of coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:69–77. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]