Abstract

Background:

Hypothyroidism is believed to be a common health issue in India, as it is worldwide. However, there is a paucity of data on the prevalence of hypothyroidism in adult population of India.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional, multi-centre, epidemiological study was conducted in eight major cities (Bangalore, Chennai, Delhi, Goa, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Ahmedabad and Kolkata) of India to study the prevalence of hypothyroidism among adult population. Thyroid abnormalities were diagnosed on the basis of laboratory results (serum FT3, FT4 and Thyroid Stimulating Hormone [TSH]). Patients with history of hypothyroidism and receiving levothyroxine therapy or those with serum free T4 <0.89 ng/dl and TSH >5.50 μU/ml, were categorized as hypothyroid. The prevalence of self reported and undetected hypothyroidism, and anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) antibody positivity was assessed.

Results:

A total of 5376 adult male or non-pregnant female participants ≥18 years of age were enrolled, of which 5360 (mean age: 46 ± 14.68 years; 53.70% females) were evaluated. The overall prevalence of hypothyroidism was 10.95% (n = 587, 95% CI, 10.11-11.78) of which 7.48% (n = 401) patients self reported the condition, whereas 3.47% (n = 186) were previously undetected. Inland cities showed a higher prevalence of hypothyroidism as compared to coastal cities. A significantly higher (P < 0.05) proportion of females vs. males (15.86% vs 5.02%) and older vs. younger (13.11% vs 7.53%), adults were diagnosed with hypothyroidism. Additionally, 8.02% (n = 430) patients were diagnosed to have subclinical hypothyroidism (normal serum free T4 and TSH >5.50 μIU/ml). Anti – TPO antibodies suggesting autoimmunity were detected in 21.85% (n = 1171) patients.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of hypothyroidism was high, affecting approximately one in 10 adults in the study population. Female gender and older age were found to have significant association with hypothyroidism. Subclinical hypothyroidism and anti-TPO antibody positivity were the other common observations.

Keywords: Anti-TPO positive, epidemiology, free T3, free T4, hypothyroidism, India, prevalence, subclinical hypothyroidism, undetected hypothyroidism

INTRODUCTION

Hypothyroidism is characterized by a broad clinical spectrum ranging from an overt state of myxedema, end-organ effects and multisystem failure to an asymptomatic or subclinical condition with normal levels of thyroxine and triiodothyronine and mildly elevated levels of serum thyrotropin.[1,2,3,4] The prevalence of hypothyroidism in the developed world is about 4-5%.[5,6] The prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism in the developed world is about 4-15%.[5,7]

In a developing and densely populated country like India, communicable diseases are priority health concerns due to their large contribution to the national disease burden.[8] In India, hypothyroidism was usually categorized under the cluster of iodine deficient disorders (IDDs), which were represented in terms of total goiter rates and urinary iodine concentrations, typically assessed in school-aged children.[9,10,11] Ever since India adopted the universal salt iodization program in 1983,[12] there has been a decline in goiter prevalence in several parts of the country, which were previously endemic.[13,14,15] In 2004, a WHO assessment of global iodine status classified India as having ‘optimal’ iodine nutrition,[16,17] with a majority of households (83.2% urban and 66.1% rural) now consuming adequate iodized salt[18,19] India is supposedly undergoing a transition from iodine deficiency to sufficiency state. A recent review of studies conducted in the post-iodization phase gives some indication of the corresponding change in the thyroid status of the Indian population.[20] However, most of these studies are limited to certain geographical areas or cities, and undertaken in children with modest sample sizes.[21,22,23,24] There have been no nationwide studies on the prevalence of hypothyroidism from India, either in the pre- or post-iodization periods. A large, cross-sectional, comprehensive study was required to provide a true picture of the evolving profile of thyroid disorders across the whole country, especially as the country is in the post-iodization era. The aim of the present study was to estimate the prevalence of hypothyroidism among the adult population in India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and enrollment criteria

This was a cross-sectional, multi-centered epidemiology study conducted at eight sites in India namely Bangalore, Chennai, Delhi, Goa, Ahmedabad, Hyderabad, Kolkata and Mumbai. These cities were selected to ensure participation of a diverse study population with respect to geographic origin, occupation, socioeconomic status and food habits. Primary outcome measure of the study was the prevalence of hypothyroidism assessed by measurement of thyroid hormones. Secondary outcome measures were the prevalence of: i) self-reported and undetected hypothyroidism, ii) sub-clinical hypothyroidism (SCH) and iii) anti-thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody positivity in the study population. All male or female natives (residing in that area for at least 5 years) aged ≥18 years, were invited to participate in a general health checkup camp, and those willing to sign a written informed consent and provide blood sample for laboratory investigations were included in the study. Participants were excluded if they were pregnant, or had any acute or chronic systemic illnesses as judged by investigator; or if they were receiving drugs (like lithium or steroids) that could interfere with thyroid function tests. The study was approved by a Central Ethics Committee (CEC) and carried out in accordance with the approved protocol, principles of Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices. It was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry India (registration no: CTRI/2011/11/002180). All participants were required to provide written informed consent before study entry.

Subjects

Enrolment of 5277 participants was planned to form a target population that constituted 0.01% of the total population of the eight cities. Sample size for each city was calculated by performing stratification according to the 2001 national census data. Participants were selected through a single visit they made to any one of the 94 general health camps organized across the eight cities. For creating awareness of each general health camp, 5000-6000 invitation leaflets were distributed door to door covering approximately five kilometers area around the camp venue, banners were exhibited at appropriate areas and 8-10 general health camp posters were displayed in the vicinity of the camps. The general health camps were led by physicians certified in internal medicine.

Study procedure

Before enrolment, participants underwent medical history assessment, a general physical examination (including anthropometry and thyroid gland examination) and laboratory investigations. A central certified laboratory performed the hematological and biochemical investigations. Assays for thyroid hormone (FT3, FT4 and TSH) were performed by the chemiluminescence method using Advia Centaur automated immunoassay analyzer (Siemens Diagnostics Tarrytown, NY, USA). Anti-TPO antibodies were measured by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using Immulite 2000 (Siemens Diagnostics Llanberis, Gwynedd, UK). Analytical sensitivity of the kit used to measure TSH, FT3, FT4 and anti-TPO antibodies was 0.010 μIU/mL, 0.1 ng/mL, 0.3 μg/dL and 5.0 IU/mL, respectively.

Based on previous thyroid history and current thyroid function test results, participants were classified using following definitions: Hypothyroid: Serum-free thyroxine (FT4) <0.89 ng/dL and thyroid stimulation hormone (TSH) >5.50 μU/mL, Hyperthyroid: Serum FT4 >1.76 ng/dL and TSH <0.35 μIU/mL, Subclinical hypothyroidism: Normal serum FT4 and TSH >5.50 μIU/mL. Subclinical hyperthyroidism: Normal serum FT4 and TSH <0.35 μIU/ml, Self-reported hypothyroidism: Subjects with history of hypothyroidism and taking levothyroxine therapy. Undetected Hypothyroidism: Subjects without history of hypothyroidism and detected to have hypothyroidism through thyroid function tests. Anti-TPO antibody positive: Presence of anti-TPO antibodies above 35 IU/ml.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS® for Windows (Version 9.2, SAS Institute). The analysis was performed on the set of all eligible subjects enrolled in the study according to the study protocol. The prevalence of hypothyroidism and other thyroid disorders was summarized as counts and percentages. A Chi-square test was used to assess the trends in the prevalence of hypothyroidism, among different age groups and gender categories. Multiple Logistic Regression was used to describe factors associated with hypothyroidism, using ‘whether the subject has hypothyroidism or not’ as the dependent variable and ‘Age’ and ‘Gender’ as the independent variables. Similar analyses were performed for SCH and anti-TPO antibody positivity.

RESULTS

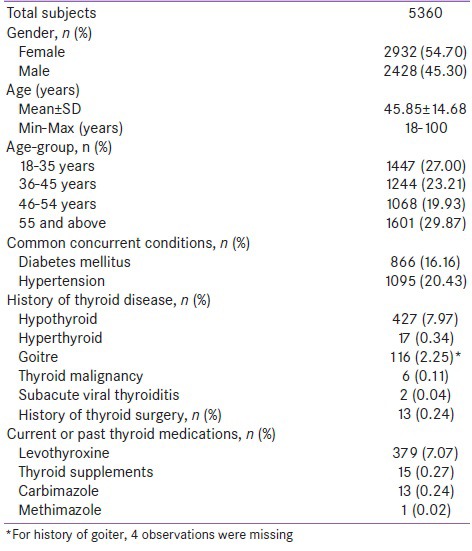

Five thousand three hundred and seventy six (5376) participants were enrolled across eight urban cities in India, from March 2011 to July 2011. Sixteen participants were withdrawn due to ineligibility (n = 11) or lack of laboratory data (n = 5). Out of the 5360 analyzable subjects, 2932 (54.70%) were females [Table 1]. The mean age of the study subjects was 45.85 with a range of 18 to 100 years. Hypertension (n = 1095; 20.4%) and diabetes mellitus (n = 866; 16.2%) were the most common concomitant diseases observed in the study population. Five hundred and ninety eight (11.15%) participants gave history of thyroid dysfunction including thyroid surgery. Thyroid medications were in current or previous use in approximately 8% (n = 408) of the population. A majority (88.27%; n = 4731) of the study population (n = 5360) was reportedly consuming iodized salt.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and thyroid related history of the study population

Hypothyroidism

The prevalence of hypothyroidism in the overall study population was 10.95% (n = 587, 95% CI, 10.11-11.78) of which 3.47% (n = 186) were previously undetected and 7.48% (n = 401) were self-reported cases. Positive history of hypothyroidism was given by 427 subjects, however only 401 of them were on thyroxine therapy. Out of these 401 self reported cases accurate dosing details of thyroxine therapy were available with 379 patients. Among these 379 patients 272 (71.77%) had a TSH <5.5 μIU/mL) on a mean dose of 1.19 mcg/kg, while the remaining (n = 107, 28.23%) had a TSH >5.5 μIU/mL on a mean dose of 1.10 mcg/kg.

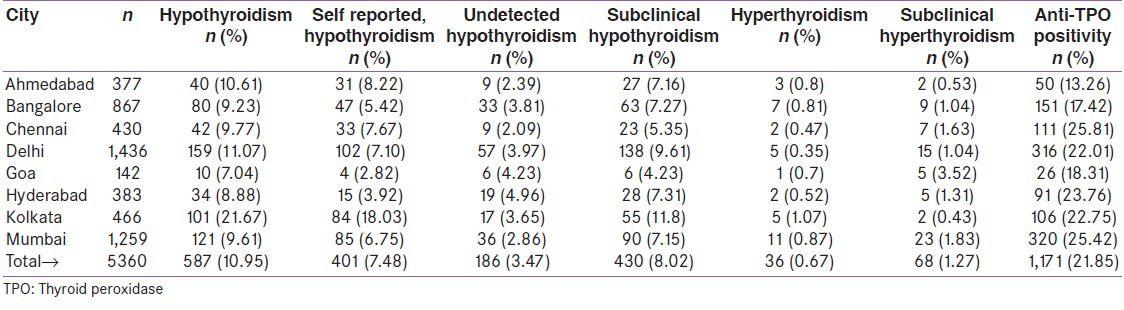

Among all cities, Kolkata recorded the highest prevalence of hypothyroidism (21.67%), while others showed comparable rates ranging from 8.88% (Hyderabad) to 11.07% (Delhi) [Table 2]. Cities located in the in-land regions of India (Delhi, Ahmedabad, Kolkata, Bangalore and Hyderabad) reported a significantly higher prevalence of hypothyroidism (11.73%) than those (Mumbai, Chennai and Goa) in the coastal areas (9.45%), P = 0.01. Logistic Regression Analysis demonstrated a statistically significant (P < 0.05) interaction of patient age and gender with the prevalence of hypothyroidism. As compared to young adults (aged 18-35 years), older adults had greater chances of being diagnosed of hypothyroidism (36-45 years: OR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.14-1.94, P = 0.0036; 46-54 years: OR = 1.53, 95% CI: 1.16-2.01, P = 0.0024; 55 years and above: OR = 1.560, 95% CI: 1.21–2.02, P = 0.0006). The prevalence of hypothyroidism was the highest in the age-group of 46 to 54 years (13.11%) and the lowest in that of 18 to 35 years (7.53%).

Table 2.

Prevalence of thyroid disorders in eight urban cities of India

A larger proportion of females than males (15.86% vs. 5.02%; P < 0.0001) were found to be affected by hypothyroidism. Females were also more likely to be detected with hypothyroidism than males (OR = 3.36, 95% CI: 2.720-4.140; P < 0.0001).

Subclinical hypothyroidism

Subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) was observed in 430 (8.02%, 95% CI: 7.29-8.74) participants. Frequency of SCH was highest (8.93%) in the age group of above 55 years and lowest in the age group of 18-35 years (6.91%), though no statistically significant association was found with age (P = 0.1534). A significantly higher number of females (8.73%) than males (7.17%, P = 0.0358) were detected to have SCH.

Anti-TPO antibodies

A total of 1171 (21.85%, 95% CI, 20.74-22.95) subjects tested positive for anti-TPO antibody. The anti-TPO positivity was consistently high, with five cities recording a prevalence of more than 20%. Lowest prevalence of anti-TPO antibodies was seen in Ahmedabad (13.26%) while highest prevalence was seen in Chennai (25.81%).

There was no significant association (P = 0.1796) between age and the presence of anti-TPO antibodies. Females showed a greater prevalence (26.04%) than males (16.81%), P < 0.05. Females in the age group of 46-54 had the highest prevalence (27.86%) of anti-TPO antibodies.

Hyperthyroidism

A total of 36 (0.67%, 95% CI, 0.45-0.89) participants including 21 females (0.72%) were diagnosed with hyperthyroidism. There was no association (P > 0.05) between hyperthyroidism and age or gender. Subclinical hyperthyroidism was seen in 68 (1.27%, 95% CI, 0.96-1.56) patients.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we assessed the nationwide prevalence of thyroid disorders, particularly hypothyroidism, in adults residing in various urban cities that represent diverse geographical regions of India. Hypothyroidism was found to be a common form of thyroid dysfunction affecting 10.9% of the study population. The prevalence of undetected hypothyroidism was 3.47% i.e., almost one-third of the hypothyroid patients (186 out of 587) were diagnosed for the first time during the course of study-related screening. This suggests that a significant proportion of patient population may go undetected and untreated even as it continues to impair the daily quality of life, work performance and economic productivity of an individual.

On the other hand, among the subjects who self-reported themselves to be hypothyroid, a significant proportion (28%) still had a high TSH value. This calls for a review of current practices in the management of thyroid disorders, including active screening of endocrine function among patients at greater risks and an emphasis on regular monitoring of the thyroid status and dose adjustments to provide effective therapy in those with established diagnosis.

In general, India is now considered to be in the post-iodization phase.[17] Our results suggest that, nationwide, the prevalence of hypothyroidism in adults is very high in this era. Unfortunately, no prevalence data exist on the occurrence of hypothyroidism among adults in the pre-iodization phase. The slight, but statistically significant increased prevalence of hypothyroidism among the inland vs. coastal cities in our study leads us to speculate whether iodine deficiency may continue to play a role in hypothyroidism in India.

The emergence of Kolkata as the worst affected city was unanticipated, particularly as the city was established to be iodine replete over a decade back.[25] However, in a comparable geographical area of Gangetic basin in West Bengal, the prevalence of hypothyroidism in 3814 subjects from all age groups was even higher (29%).[26] The high prevalence figures in Kolkata have ascertained that thyroid disorders in India are not confined to the conventional iodine-deficient sub-Himalayan zone but also extended to the plain fertile lands. A possible etiological role of cyanogenic foods acting as goitrogens to interfere with iodine nutrition has been previously suggested for, but not limited to this area.[27,28] Increasing exposure to thyroid disruptors including industrial and agricultural contaminants has been identified as a growing health concern throughout India.[29]

There was a predominance of thyroid dysfunction in women in our study, and is consistent with worldwide reports, especially those in midlife (46-54 years). Given the association between thyroid disorders and cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and dyslipidemia,[30] the prevalence figures noted for women in this study draw attention to the growing health needs of this important segment of the Indian population.

Another significant observation was that approximately one fifth of the study population had anti-TPO positivity, which is an established marker of autoimmune thyroid disease.[31] There seems to be a steady rise in the prevalence of anti-TPO positive in India. In a study conducted from 2007 to 2010 in Delhi, the percentage of adults testing TPO antibody positive was 13.3%;[32] the figure was 22.01% in the current study. A similar increase was apparently observed in the southern part of India. Earlier, Kerala saw a 16.7%[33] prevalence of anti-TPO positivity in adults, and the rate in a neighboring state (represented by Chennai) reported in the current study is 25.81%. Reasons for the increase in anti-TPO positivity remain unclear; the underlying pathogenesis may involve a complex interplay of genetic, environmental and endogenous factors.[15,34,35,36]

Our study has important limitations: Firstly, it was done in urban India, and the prevalence of hypothyroidism in rural India remains unknown. Secondly, from the consumption of iodized salt, the study presumed that the target population was iodine sufficient, without testing for reliable markers such as iodine content in salt samples or urinary iodine excretion.[37] Thus, with regard to the cause of hypothyroidism, there may be etiological factors other than the iodization status.

To summarize the present study is to first provide nationwide data on the prevalence of hypothyroidism in the adult population. The study shows a high prevalence of hypothyroidism and positivity to anti-TPO antibodies. This poses a public health concern and an important challenge to the policy makers and health professionals.

CONCLUSIONS

Hypothyroidism is a commonly prevailing disorder in adult Indian population. Older overweight females seem to be more prone. Autoimmune mechanisms appear to play an etiological role in a significant proportion of patients. Iodine intake ceases to be the sole etiological contender for thyroid disorders in urban areas. Identification of multiple risk factors and plausible underlying mechanisms is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was funded by Abbott India Limited. The authors acknowledge the valuable contribution of the following participating investigators (centers in alphabetical order): Dr. Sanjeev Phatak, MD (Ahmedabad), Dr. Arun Vadavi, MD (Bangalore), Dr. E. Prabhu, MD (Chennai), Dr. Raj Kumar Lalwani, MD (Delhi); Dr. Rufino Monteiro, MD (Goa), Dr. Loy Camoens, MD (Hyderabad); Dr. Mary D’Cruz, MD (Kolkata) and Dr. Mahesh Padsalge, MD (Mumbai).

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Cooper DS. Clinical practice. Subclinical hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:260–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107263450406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts CG, Ladenson PW. Hypothyroidism. Lancet. 2004;363:793–803. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15696-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biondi B, Klein I. Hypothyroidism as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Endocrine. 2004;24:1–13. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:24:1:001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krassas GE, Poppe K, Glinoer D. Thyroid function and human reproductive health. Endocr Rev. 2010;31:702–55. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, Hannon WH, Gunter EW, Spencer CA, et al. Serum TSH, T (4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:489–99. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoogendoorn EH, Hermus AR, de Vegt F, Ross HA, Verbeek AL, Kiemency LA, et al. Thyroid function and prevalence of anti-thyroperoxidase antibodies in a population with borderline sufficient iodine intake: Influences of age and sex. Clin Chem. 2006;52:104–11. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.055194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bemben DA, Hamm RM, Morgan L, Winn P, Davis A, Barton E. Thyroid disease in the elderly. Part 2. Predictability of subclinical hypothyroidism. J Fam Pract. 1994;38:583–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.New Delhi: Background Papers-Burden of Disease in India; 2005. National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sood A, Pandav CS, Anand K, Sankar R, Karmarkar MG. Relevance and importance of universal salt iodization in India. Natl Med J India. 1997;10:290–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapil U, Saxena N, Ramachandran S, Balamurugan A, Nayar D, Prakash S. Assessment of iodine deficiency disorders using the 30 cluster approach in the National Capital Territory of Delhi. Indian Pediatr. 1996;33:1013–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dodd NS, Godhia ML. Prevalence of iodine deficiency disorders in adolescents. Indian J Pediatr. 1992;59:585–91. doi: 10.1007/BF02832996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tiwari BK, Ray I, Malhotra RL. New Delhi: Government of India; 2006. Policy Guidelines on National Iodine Deficiency Disorders Control Programme-Nutrition and IDD Cell. Directorate of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toteja GS, Singh P, Dhillon BS, Saxena BN. Iodine deficiency disorders in 15 districts of India. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:25–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02725651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marwaha RK, Tandon N, Gupta N, Karak AK, Verma K, Kochupillai N. Residual goitre in the postiodization phase: Iodine status, thiocyanate exposure and autoimmunity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;59:672–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapil U, Sharma TD, Singh P. Iodine status and goiter prevalence after 40 years of salt iodisation in the Kangra District, India. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:135–7. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geneva: WHO; 2004. Iodine status worldwide, WHO global database on iodine deficiency, Department of nutrition for health and development. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersson M, Takkouche B, Egli I, Allen HE, Benoist B. Current global iodine status and progress over the last decade towards the elimination of iodine deficiency. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:518–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sunderesan S. Progress achieved in universal salt iodization programme in India. In: Prakash R, Sunderesan S, Kapil U, editors. Proceedings of symposium on elimination of IDD through universal access to iodized salt. New Delhi: Shivnash Computers and Publications; 1998. pp. 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yadav K, Pandav CS, Karmarkar MG. Adequately iodized salt covered seventy-one percent of India in 2009. [Last accessed on 2012 Jun 11];IDD newsletter. 2011 39:2–5. Available from: http://www.seen.es/pdf/IDD%20NL%20email%20May%202011.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unnikrishnan AG, Menon UV. Thyroid disorders in India: An epidemiological perspective. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15:S78–81. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.83329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao RS, Kamath R, Das A, Nair NS, Keshavamurthy Prevalence of goitre among school children in coastal Karnataka. Indian J Pediatr. 2002;69:477–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02722647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sankar R, Moorthy D, Pandav CS, Tiwari JS, Karmarkar MG. Tracking progress towards sustainable elimination of iodine deficiency disorders in Bihar. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73:799–802. doi: 10.1007/BF02790389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapil U, Sethi V, Goindi G, Pathak P, Singh P. Elimination of iodine deficiency disorders in Delhi. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:211–2. doi: 10.1007/BF02724271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marwaha RK, Tandon N, Garg MK, Desai A, Kanwar R, Sastry A, et al. Thyroid status two decades after salt iodization: Country-wide data in school children from India. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012;76:905–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinha RK, Bhattacharya A, Roy BK, Saha SK, Nandy P, Doloi M, et al. Body iodine status in school children and availability of iodised salt in Calcutta. Indian J Public Health. 1999;43:42–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandra AK, Tripathy S, Mukhopathyay S, Lahari D. Studies on endemic goitre and associated iodine deficiency disorders (IDD) in a rural area of the Gangetic West Bengal. Indian J Nutr Diet. 2003;40:53–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandra AK, Tripathy S, Lahari D, Mukhopadhyay S. Iodine nutritional status of school children in a rural area of Howrah district in the Gangetic West Bengal. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;48:219–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chandra AK, Mukhopadhyay S, Lahari D, Tripathy S. Goitrogenic content of Indian cyanogenic plant foods and their in vitro anti-thyroidal activity. Indian J Med Res. 2004;119:180–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalra S, Unnikrishnan AG, Sahay R. Thyroidology and public health: The challenges ahead. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15:S73–5. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.83326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luboshitzky R, Herer P. Cardiovascular risk factors in middle-aged women with subclinical hypothyroidism. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2004;25:262–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demers LM, Spencer CA. Laboratory medicine practice guidelines: Laboratory support for the diagnosis and monitoring of thyroid disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;58:138–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marwaha RK, Tandon N, Ganie MA, Kanwar R, Garg MK, Singh S. Status of thyroid function in Indian adults: Two decades after universal salt iodization. J Assoc Physicians India. 2012;60:32–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Usha Menon V, Sundaram KR, Unnikrishnan AG, Jayakumar RV, Nair V, Kumar H. High prevalence of undetected thyroid disorders in an iodine sufficient adult south Indian population. J Indian Med Assoc. 2009;107:72–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gopalakrishnan S, Singh SP, Prasad WR, Jain SK, Ambardar VK, Sankar R. Prevalence of goitre and autoimmune thyroiditis in schoolchildren in Delhi, India, after two decades of salt iodisation. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19:889–93. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2006.19.7.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papanastasiou L, Vatalas IA, Koutras DA, Mastorakos G. Thyroid autoimmunity in the current iodine environment. Thyroid. 2007;17:729–39. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brent GA. Environmental exposures and autoimmune thyroid disease. Thyroid. 2010;20:755–61. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.WHO/UNICEF/ICCIDD. Geneva: WHO/NUT/94.6; 1994. Indicators for assessing Iodine Deficiency Disorders and their control through salt iodization. [Google Scholar]