Abstract

Background:

A low-glycemic index diet is effective in blood glucose control of diabetic subjects, reduces insulin requirement in women with gestation diabetes mellitus (GDM) and improves pregnancy outcomes when used from beginning of the second trimester. However there are limited reports to examine the effect of low glycemic load (LGL) diet and fiber on blood glucose control and insulin requirement of women with GDM. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the effect of low glycemic load diet with and without fiber on reducing the number of women with GDM requiring insulin.

Materials and Methods:

All GDM women (n = 31) were randomly allocated to consume either a LGL diet with Fiber or LGL diet.

Results:

We found that 7 (38.9%) of 18 women with GDM in Fiber group and 10 (76.9%) in “Without Fiber” group required insulin treatment.

Conclusion:

The LGL diet with added fiber for women with GDM dramatically reduced the number needing for insulin treatment.

Keywords: Low glycemic load diet, gestational diabetes, wheat bran

INTRODUCTION

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as “carbohydrate intolerance resulting in hyperglycemia with first recognition during pregnancy. The GDM affects a substantial number of pregnancies. The overall incidence of 3-6% has steady increased over time, ranging from 2.2% in South America to 15% in the India.[1]

Maternal hyperglycemia causes a greater transfer of glucose to the fetus, causing fetal hyperinsulinemia and an overgrowth of insulin-sensitive (mainly adipose) tissues, with excessive fetal growth, resulting in more trauma at birth, shoulder dystocia and perinatal deaths.[2] Carbohydrate is main dietary source for fetal brain development and at least 175 g/day of carbohydrates are recommended in the pregnant women.[3] Carbohydrates intake with a low-glycemic index (GI) result in smaller increase in postprandial glucose concentration than after high GI diet in normal and also type 2 diabetic patients.[4,5] Ingestion of 25 g fiber induces 10-15% reduction in 2 hr postprandial glucose level in impaired glucose tolerance subjects,[6] and lower dietary fiber intake and higher dietary glycemic load (GL) are positively related to the incident of GDM.[7] The medical nutrition therapy (MNT) is the cornerstone approach to treatment of women with GDM,[8] and almost up to 80-90% cases of GDM can be effectively managed with MNT.[1] However limited information is available to allow evidence-based recommendations regarding specific nutritional approaches such as total calories, nutrient distribution, fiber content, GI and GL to the management of GDM.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the role of low GI-low GL diet in postprandial blood concentration, specifically the effect of wheat bran on blood glucose of GDM subjects and on reducing the number of women with GDM requiring insulin. We hypothesized that low GI-low GL diet ingested with wheat bran compared with low GI-low GL diet would improve postprandial blood glucose of GDM subjects and reduces the number of women with GDM requiring insulin, because of lowering GI value.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thirty six GDM women (aged 20-40), pre-pregnancy BMI = 18.5-29, and at their gestation age of 24-28 weeks who were referred to endocrine clinic were recruited for this study. The diagnostic criteria for GDM was based on the ‘standards of medical care in diabetes’ and HAPO study.[8,9] The proposed criteria for the 75g, OGTT considered that any of the following thresholds be met or exceeded.

Fasting plasma glucose 92 mg/dl

One-hour plasma glucose 180 mg/dl

Two-hour plasma glucose 153 mg/dl

The monitoring criteria for GDM considered as fasting plasma glucose ≤ 90 mg/dl and 2 hr PP plasma glucose ≤ 120 mg/dl.[8]

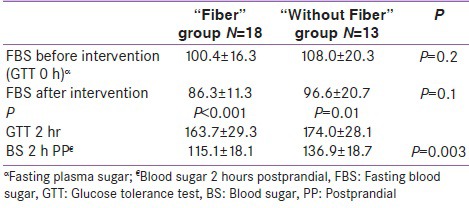

Patients were either IFG (FBS > 92, impaired fasting glucose) or IGT (FBS < 92; IGT 1 h, 2 h > 180, 153 mg/dl; impaired glucose tolerance). IFG patients randomly allocated to “Fiber group” and “Without Fiber” group, also IGT patients were randomized the same manner in two diet groups. There were similar number of IFG patients in each group of “Fiber” and “Without Fiber” group. Similarly the IGT patients were equal in each group. In fact we eliminated the confounding factors by allocating similar blood glucose level in each group and the difference in FBS in two groups at the beginning was not significant [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of blood glucose concentration between “Fiber” and “Without Fiber” groups

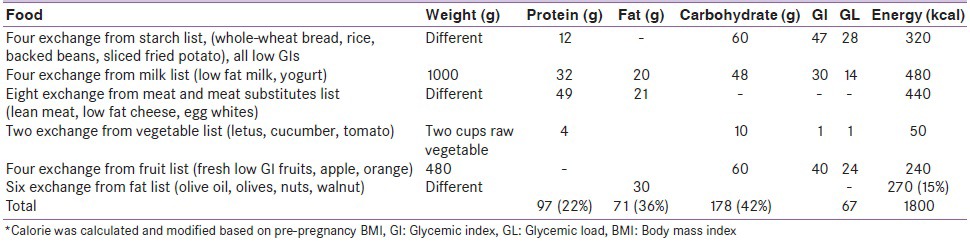

Dietary plane

The LGIs-LGLs ascribed to the foods used have been taken from international and local published data.[10,11] The diet in the two weeks experimental period consisted of ordinary food item having GI ≤ 55 and each main meal had GL ≤ 20 with overall daily GL = 67-72. Subjects were received LGI-LGL or LGI-LGL plus 15g wheat bran in each main meal. This was accomplished by providing a list to each individual of the recommended daily intake of commonly used foods and a substitution list allowing exchanges within food groups. According to American Diabetes Association (ADA), we recommended a daily calorie intake of 30 kcal/kg body weight plus 340 kcal/day for women with a normal pre-pregnancy weight (BMI = 19.8-26) and 24 kcal/day (plus 340 kcal/daily) for women with pre-pregnancy overweight (BMI = 26.1-29).[12] The nutrients distribution were almost based on ADA[12] guideline [Table 1] and the calorie intake was distributed in three main meals and three between meals and bed time. Subjects were ordered to do their daily routine life style during intervention. After two weeks women who achieved FBS and BS 2 hr pp blood glucose control continued their diet, otherwise commenced insulin treatment

Table 1.

Composition of low glycemic load diet with 1800 kcal administrated to diabetics patients*

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean ± SD. Blood glucose data were analyzed by independent sample t-test and Chi-square test to compare blood glucose concentration before and after intervention and between two groups of “Fiber” and “Without Fiber”.

Blood glucose monitoring

After two weeks dietary intervention plasma blood glucose monitored using fasting blood glucose and 2 hours postprandial plasma blood glucose.

Statement of ethics

The protocol was approved by the Qazvin University of Medical Science, Human Ethics Committee and each subjects provided informed consent prior to participation. We certify that all applicable institutional regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during this research.

RESULTS

Five women in “Without Fiber” group at last stage of study withdrew from study and did not complete the study. We continue the study with 18 subjects in “Fiber” group and 13 subjects in “Without Fiber” group. Based on diagnosis of GDM all participated subjects were diabetes without significant differences in fasting blood glucose of two groups at the beginning of the study (100.4 ± 16.3 and 108.0 ± 20.3 in “Fiber” and “Without Fiber” groups respectively, P = 0.2). In “Fiber” group fasting blood glucose concentration before intervention and after intervention were 100.4 ± 16.3 and 86.3 ± 11.3 respectively which resulted in 14% (14 mlg/dl) reduction (P = 0.001). Similarly, these changes in “Without Fiber” group were 108.0 ± 20.3 and 96.6 ± 20.7 respectively with 12% (12 ml/dl) reduction (P = 0.01). Similarly 2 hr pp blood concentration in “Fiber” and “Without Fiber” group reduced by 29.6% and 21.3% respectively compare to 2 hr GTT. However comparing fasting blood glucose after two weeks period of intervention in two groups was not significant (P = 0.1) [Table 2].

The postprandial blood glucose in two groups of “Fiber” and “Without Fiber” after intervention were 115.1 ± 18.1 and 136.9 ± 18.7 respectively, which the difference was significant (P = 0.003) [Table 2].

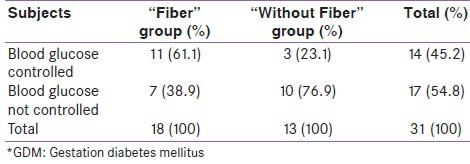

Regarding to blood glucose control based our study's criteria, 11 (61.1%) patients in “Fiber” group and 3 (23.1%) patients in “Without Fiber” groups achieved blood glucose control (Chi-square, P = 0.04) [Table 3]. In other word 7 (38.9%) in “Fiber” group and 10 (76.9%) in “Without Fiber” group required insulin treatment. In comparison with “Without Fiber” group, patients who consumed fiber demonstrated OR of 5.2 in achieving blood glucose control (P = 0.04)

Table 3.

Crosstab, effect of low glycemic load diet with and without fiber on blood glucose of GDM* subjects

DISCUSSION

This study revealed that, the low-glycemic load diet significantly reduces blood glucose concentration and specifically the low-glycemic load diet with added 15 gr fiber had clinically significant effect on post prandial blood glucose of GDM patients.

Our previous studies has demonstrated that the low glycemic load diet has significant effect on blood glucose reduction of diabetic subjects[13] and wheat bran in normal diet significantly reduces postprandial glucose response of subjects with impaired fasting glucose (IFG).[6] Although, there are limited studies about the usefulness of a low-glycemic index diet in pregnancy,[14] one study demonstrated that consumption of a low-glycemic index diet from the beginning of the second trimester resulted in better fetal outcomes.[15] The monitoring criteria for GDM is considered as fasting plasma glucose ≤ 90 mg/dl and 2 hr PP plasma glucose ≤ 120 mg/dl after starting the meal.[8] This can be achieved by administration of low glycemic load diet or diet containing sufficient fiber to delay obsorbtion of carbohydrate. In our previous study, the LGL diet significantly effect on FBS and HbA1c of diabetic patients[13] and administration of 25 gr wheat bran to normal diet of IFG subjects resulted in 11% reduction in blood glucose response in compare to control group.[6] Two other reports also have shown the advantages of a low-glycemic index diet for the management of subjects with type 2 diabetes.[16,17]

In current study 15 gr wheat bran intake by GDM subjects reduced the fasting blood glucose concentration by 16.1%, which was comparable with 11.8% reduction in “LGL” control diet. Similarly 2 hrs pp blood concentration reduced by 29.6% and 21.3% in “Fiber” and “Without Fiber” group respectively compare to 2 hrs GTT. We found that 7 (38%) of 18 women in Fiber group and 10 (76%) in “Without Fiber” group needed insulin treatment. In similar study conducted in Wollongong city in Australia.[18] Of the 31 women randomly assigned to a low-glycemic index diet, 9 (29%) required insulin, and a significant higher proportion, 19 out of 32 (59%) women who assigned to a higher glycemic index diet underwent insulin treatment. While there were similar a minimum amount of around 175 g/day LGI carbohydrate in both studies, the differences can be explained by different GDM diagnosed and monitoring criteria approached in two studies. In our study GDM diagnosis was according to guideline of the “Standards of medical care in diabetes”,[8] while in Wollongong study GDM diagnosis was based on the modified Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society (ADIPS) criteria;[19] fasting blood glucose level (BGL) ≥5.5 mmol/L (_100 mg/dl), 1 hr BGL ≥ 10.0 mmol/L (_181 mg/dl), or 2 hrs BGL ≥ 8.0 mmol/L (_145 mg/dl) vs. 92, 181, 152 mg/dl in our study. Also in another study conducted by Louie et al.,[20] in comparing LGI diet (GI ≤ 50) with high fiber diet (GI ~ 60) among 99 GDM women, 53% of first group vs. 65% in second group required insulin treatment.

The mechanism behind the fact that the LGL diet plus fiber intake was more effective in blood glucose of GDM subjects is that fiber slows carbohydrate absorption and reducing GI of meal. It is worthy to notice that the most of the GDM women in our study who were candidate for insulin treatment were unwilling to commence insulin treatment and 6 of them in “Without Fiber” group switched to “Fiber” group. Similarly, 47% of the women in the Wollongong study,[18] in high-GI group who met the criteria for insulin commencement avoided insulin by switching to an LGI diet.

Our current study has strength and limitation. The strengths are that the LGL with fiber diet is not harsh treatment and is acceptable by patients. The limitation of study is that the LGL diet which contains low carbohydrate percentage is not food habits of patients and food choice limitation may not result in sufficient weight gain that is goal of pregnant women. However the diet will be ideal to GDM women with BMI > 25 which need the minimum of weight gain during pregnancy.

In summary our finding was consistence with others finding. Low glycemic index diet containing extra added fiber for women with GDM is appropriate, safe and well tolerated and a low GL diet with fiber significantly reduces the need for the use of insulin.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was funded by Qazvin Metabolic Diseases Research Center, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Magon N, Seshiah V. Gestational diabetes mellitus: Non-insulin management. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15:234–53. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.85580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lapolla A, Dalfra M, Fedele D. Management of gestation diabetes mellitus. Diabetic Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. 2009;2:73–82. doi: 10.2147/dmsott.s3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Washington DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Science; 1990. Food and Nutrition Board. Nutrition during pregnancy. Part 1: Weight gain. Part 2: Nutrient supplement. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afaghi A, O’Connor H, Chow CM. High-glycemic-index carbohydrate meals shorten sleep onset. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:426–30. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizkalla SW, Taghrid L, Laromiguiere M, Huet De, Boillot J, Rigoir A, et al. Improved plasma glucose control, whole-body glucose utilization, and lipid profile on a low-glycemic index diet in type 2 diabetic men. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1866–72. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.8.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Afaghi A, Omidi R, Sarreshtehdari M, Ghanei L, Alipour M, Azadmehr A, et al. Effect of wheat bran on postprandial glucose response in subjects with impaired fasting glucose. Curr Top Nutraceutical Res. 2011;9:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang C, Liu S, Solomon C, Hu F. Dietary fiber intake, dietary glycemic load, and the risk for gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2223–30. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Care diabetesjournal.org, Standards of medial care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012:S11–63. doi: 10.2337/dc12-s011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metzger B, Lowe L, Dyer A, Trimble E, Chaovarinder U. HAPO Study cooperative research group, hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1991–2002. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brand-Miller JC. Home of the glycaemic index, glycaemic load. [Last accessed on 2012 May 10]. Internet: Available from: http://www.glycemicindex.com .

- 11.Taleban FA, Esmaeili M. Tehran: National nutrition and food technology of Iran, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science; 1999. Glycemic index of Iranian foods: Guideline for diabetic and hyperlipidemic patients. [Google Scholar]

- 12.American diabetes association. Gestational diabetes mellitus (position statement) Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl 1):S88–90. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Afaghi A, Ziaee A. Effect of low glycemic load diet on glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) in poorly-controlled diabetes patients. Glob J Health Sci. 2012:4. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v4n1p211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dietary advice in pregnancy for preventing gestational diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD006674. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006674.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moses R, Luebcke M, Davis W, Coleman K, Tapsell L, Petocz P, et al. The effect of a low-glycemic index diet during pregnancy on obstetric outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:807–12. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolever T, Mehling C, Chiasson JL, Josse R, Leiter LA, Maheux P, et al. Low glycaemic index diet and disposition index in type 2 diabetes (the Canadian trial of Carbohydrates in Diabetes): A randomisedcontrolled trial. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1607–15. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, McKeown-Eyssen G, Josse RG, Silverberg J, Booth GL, et al. Effect of a low glycemic index or a high cereal fiber diet on Type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2008;300:2742–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moses RG, Barker M, Winter M, Petocz P, Brand-Miller JC. Can a low-glycemic index diet reduce the need for insulin in gestational diabetes Mellitus? Diabetes Care. 2009;32:996–1000. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman L, Nolan C, Wilson J, Oats J, Simmons D. Gestational diabetes mellitus management guidelines: The Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society. Med J Aust. 1998;169:93–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb140192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Louie J, Markovic T, Perera N, Foote D, Petocz P, Ross G, et al. A randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of a low-glycemic index diet on pregnancy outcomes in gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2341–6. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]