Abstract

The increasing rate of opiate pain reliever (OPR) use is a pressing concern in the United States. This article uses a drug epidemics framework to examine OPR use among arrestees surveyed by the Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring program. Results demonstrate regional and demographic variation in use across nine focal cities. High rates of OPR use on the West Coast illustrate the expansion of use from its initial epicenter. By 2010, OPR use had plateaued in all focal cities. Findings suggest directions for ongoing research into pathways to use and vectors of diffusion and for regionally specific interventions sensitive to age and ethnic diversity.

Keywords: drug epidemics, opiate pain relievers, arrestees

INTRODUCTION

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011) announced that deaths from prescription painkillers reached epidemic proportions, surpassing deaths from heroin and cocaine overdose combined. To address the increasing concerns regarding opiate pain reliever (OPR) misuse in the United States, this article uses a drug epidemic perspective that has been used to study dynamic changes in the popularity of other substances. The strength of this approach is that it builds on the underlying social nature of a drug’s use in a particular place at a particular time. The developed framework explores the past course of a drug epidemic, indicates where we are within a current epidemic, and identifies the expected changes for the near-term future. Findings are of value to drug treatment providers, law enforcement, and policy makers committed to curtailing the misuse of OPRs by designing carefully tailored interventions for those user subpopulations experiencing the greatest harm from them. The background section that follows presents a summary of the recent literature on opiate use within the context of a drug epidemics framework.

BACKGROUND

The Drug Epidemics Framework

For many years, empirical research into substance abuse trends have drawn on disease epidemics as a model for understanding the changes over time in use of illicit drugs (Becker, 1967; Behrens, Caulkins, Tragler, & Feichtinger, 2002; Hamid, 1992; Hunt & Chambers, 1976; Johnston, 1991; Musto, 1993, 1999; Winkler, Caulkins, Behrens, & Tragler, 2004). As empirical research has demonstrated, the course of a drug epidemic is often mathematically similar to disease outbreaks (Anderson & May, 1991) and to other diffusion of innovation phenomena, such as the spread of new agricultural technology, teaching methods, or fashions (Katz, Levin, & Hamilton, 1963; Rogers, 1995). Golub and his colleagues have identified four distinct phases—incubation, expansion, plateau, and decline—that characterized the rise and decline of the Crack Epidemic, its expected course for the near future, and the variation across locations (Bennett & Golub, 2012; Golub & Johnson, 1994, 1996, 1997; Johnson, Golub, & Dunlap, 2006). This framework (depicted in Figure 1 ) has been used to analyze the emergence of the Marijuana/Blunts 1 Epidemic of the 1990s (Golub, 2005; Golub & Johnson, 2001; Golub, Johnson, Dunlap, & Sifaneck, 2004), the Heroin Injection Epidemic in the 1960s and early 1970s (Golub & Johnson, 2005; Johnson & Golub, 2002), and an increase in the use of hallucinogens and ecstasy/MDMA 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine during the 1990s (Golub, Johnson, Sifaneck, Chesluk, & Parker, 2001). For each of these epidemics, increasing patterns of use, particularly among youth, were closely linked to processes of subcultural change (Golub et al., 2005).

FIGURE 1.

The four phases of drug epidemic (A Theoretical Perspective; color figure available online).

Incubation phase

A drug epidemic typically starts among a highly limited subpopulation in which the significance of cultural practices surrounding use is developed and refined. Ethnographic research has indicated that the incubation phases for recent drug epidemics have been associated with specific contexts involving social gatherings, music, and fashion. For example, the Heroin Injection Epidemic originated in the jazz music scene (Jonnes, 2002), the Crack Epidemic originated with inner-city drug dealers at after-hours clubs (Hamid, 1992), and the Marijuana/Blunts Epidemic originated in the hip-hop movement (Sifaneck, Kaplan, Dunlap, & Johnson, 2003).

Expansion phase

Sometimes, pioneering drug users successfully introduce their practices to the broader population, resulting in a rapidly escalating number of new users. During this period, the number of users initially increases exponentially, as is common with diffusion of innovation and disease epidemic processes. This rapid growth then tapers off, resulting in the S-shape depicted in Figure 1. This period of rapid expansion often leads to opinion leaders and media outlets decrying the drug as a scourge that is sweeping the nation (Brownstein, 1991; Hartman & Golub, 1999; Jenkins, 1999; Reinarman & Levine, 1997).

Plateau phase

Eventually, those with greatest risk of using a particular drug (typically those who use other illicit drugs) have either initiated use or at least had the opportunity to do so. This point marks the end of expansion and the beginning of the plateau phase. For a time, widespread use prevails. During this period, youth coming of age who become involved with drug use typically use drugs that are currently popular, determined by which drug epidemics are in their plateau phase. These youth come to constitute a drug generation for whom the use of a drug comes at a critical period of their development and takes on special significance.

Decline phase

Eventually, the use of a particular drug declines in popularity. The process may involve the emergence of new conduct norms that hold that use of that drug is dangerous, unsavory, or simply old-fashioned. Similarly, a new drug may emerge to take its place among users because it is less expensive or more readily available or because its effects are preferable . These phenomena are well illustrated by the decline of the Crack Epidemic. Ethnographic research revealed that early in the decline phase of the Crack Epidemic the word crackhead became a dirty word in inner-city New York, and youths avoided peers they suspected had used crack (Curtis, 1998; Furst, Johnson, Dunlap, & Curtis, 1999). During this period, youths marijuana use increased, suggesting the increase in marijuana use was related to the decline in crack use (Golub & Johnson, 2001). Such a shift in the prevailing youth culture marks the start of a decline phase. The subsequent diffusion of anti-use sentiment then competes with the prevailing pro-use norms. This leads to a gradual decline phase of a drug epidemic. During the decline phase, a decreasing proportion of youths coming of age become users. However, the overall use of the drug endures for many years as some members of a drug generation continue their habits.

The Opiate Pain Reliever Epidemic in the United States

This section uses the drug epidemics perspective as a framework for reviewing the prior literature on recent trends in OPR use. OPRs have emerged as a pressing topic for public health research due to their potential to create dependence in frequent users and to present risks of overdose and death, particularly when combined with other central nervous system depressants, such as tranquilizers and alcohol. Although these hazards have been recognized by medical and public health officials, like other drug epidemics, OPR use in the mid-1990s was driven by key distribution, pharmaceutical, and administration innovations.

Incubation

During the mid-1990s, Internet pharmacies offering online consultations and prescriptions became popular—an innovation that was central to the emergent OPR Epidemic (Collins & McAllister, 2006; Forman, 2003; Lessenger & Feinberg, 2008; Lineberry & Bostwick, 2004). During this same period, the pure synthetic Fentanyl, which is more than 100 times more powerful than morphine, reached illicit markets, where its sale (sometimes as heroin), has been linked to at least 12 overdose deaths , primarily in California (Henderson, 1991). Purdue Pharmaceutical’s new formulation of oxycodone (branded OxyContin) also brought OPRs into the spotlight as substances with serious abuse and overdose potential, especially at the higher doses (80 and 160 mg) that were being marketed and prescribed. Although OxyContin was marketed for its palliative efficacy resulting from an extended-release coating, this feature of the drug was circumvented by users who crushed and separated the tablets to snort (Young, Havens, & Leukefeld, 2010) or inject it (Havens, Walker, & Leukefeld, 2007; Lankenau et al., 2011; McLean & Bruno, 2010).

Beyond these three areas of innovation in the way OPRs were formulated, distributed, and administered, little is known about important geographical and social dimensions of the incubation period for the OPR Epidemic. Shortly after OxyContin’s release in 1996, observers noted that OxyContin was being abused among rural populations in Maine and Appalachia, and news media began referring sensationally to the rise of hillbilly heroin (Tunnell, 2004). One study using a key informant network to track OPR abuse found a general tendency in 2002-2004 for the epidemic to “migrate from the Northeast and Appalachia to the Southeast and West” (Cicero, Inciardi, & Muñoz, 2005, p. 667), although the authors provided no explanation for the mechanism behind this geographical diffusion and ethnic and other demographic shifts were not included in the analysis.

Much of the current attention to the OPR Epidemic has been focused on youth (Compton & Volkow, 2006b). Other reports suggest the root of OPR use may be among aging populations, possibly resulting from social isolation and other stressors (Gfroerer, Penne, Pemberton, & Folsom, 2003; Han, Gfroerer, & Colliver, 2009). The pathways between use among older and younger individuals would appear to be complex. Many of the OPRs being diverted by youth come from their parents’ medicine cabinets (Friedman, 2006). On the other hand, the flow of drugs is bidirectional. Approximately half of Michigan high school students who diverted medications reported providing them to a parent (Boyd, McCabe, Cranford, & Young, 2007).

Evidence for Expansion

Some speculate that the OPR Epidemic has become a part of a prevailing youth drug culture, with its own distinct social contexts for use and behavioral expectations. Several major news outlets have covered the emergence of what have been dubbed “pharm parties” at which teens reportedly contribute pharmaceuticals stolen from their parents’ medicine cabinets to collective bowls from which party goers take handfuls of random drugs, sometimes referred to as trail mix (Bernstein, 2008; Jones, 2008; Leinwand, 2006). However, other reports dispute these claims, contending that adolescents are far more discriminating in their use of pharmaceutical drugs and that the pharm party is a myth concocted by unscrupulous news media (Shafer, 2008). Another potential vector for the reported expansion of OPR use among adolescents (and African American youth in particular) is the use of codeine and promethazine hydrochloride cough syrup—known as lean, purple drank, or sizzurp (Peters et al., 2003; U.S. Department of Justice, 2011b). This use has been celebrated in the recent work by several Southern African American hip-hop artists (Mann, 2011). Lil Wayne’s anthem “Me and My Drank,” extols the benefits of codeine syrup and makes a request that the artist not be judged for using it:

My girl trippin’ and damn I gotta hear my momma mouth

My homeboys say I should slow down a little

But this shit that I’m on make me slow down a lot …

This is how we do it, do it in the South

One more ounce will make me feel so great

Wait … now I can’t feel my face …

And everybody please, please don’t judge me

Will somebody please, please double cup me. 2 (Lil Wayne & Short Dawg, 2010)

Frayser Boy’s “I Got Dat Drank” describes the slowing effect of codeine/ promethazine syrup, as well as its potential effects on one’s conversational competence:

I’m getting full of drank leanin’ movin slow seeming

Unda the influence will make you fall asleep dreaming …

Yeah I know these suckas on the town gotta hate me

Doin’ real big and my system full of that promethazine

Have you kinda dumb, sayin’ thangs that you don’t really mean …

Once that codeine hits your system it gon’ make you lean

Another fiend, compliments of promethazine (2005)

Slim Thug’s “Leanin” presents a celebration of the Houston (H-town) hiphop and (vintage) automobile subculture and the pleasures of driving under the influence of hydroponic cannabis and lean:

I’ma young ghetto boy, that’s why I act this way

Rollin’ in the candy car, leanin’ sittin’ sideways …

Drank and dro, got me floss mode, doin’ a hundred on the toll road

Slab crusha, dome busta, promethazine mixed with the tussa …

Ten years, still putting it down, representin’ for that H-town. (2009)

Other tributes to codeine/promethazine indicate that the trend has moved beyond the South, such as Philadelphia rapper Beanie Sigel’s “Purple Rain,” which begins with a medical warning:

Caution

Do Not Mix Wit’ Alcohol

It May Cause Drowsiness

Keep Out Of Reach of Small Children

Promethazine wit’ Codeine? That’s My twizist

It might lean you to the left, or make you izitch …

Yo be careful, It ain’t ya ordinary liquid

The first time you sip it, you might get addicted

Matter of fact, I know you’re gonna get addicted

Cause it’s so sweet, life liquid, plus it’s good for your sickness (Siegel, 2005)

Jim Jones’ song “What You Been Drankin’ On?” suggests that true intoxication requires the dangerous combination of sizzurp and Hennessey Cognac (affectionately, “Henny”):

Cuz you ain’t drunk, Nigga

You ain’t drunk, Nigga

Til’ that sizzurp and Henny is in yo’ cup, Nigga (Jones, 2005)

Although much of the music making explicit reference to codeine/promethazine syrup is fundamentally glorifying, the high risk of addiction and resulting legal issues are also central themes in several works, such as Z-RO’s “I Can’t Leave Drank Alone”:

I can’t leave drank alone, it got a Nigga fiendin’

I ain’t even gonna lie, this drank got me feelin’ like I’m walkin’ on the sky

Y’all would think after 3 felony cases

I would leave drank alone

But I’m still out on bond

And I’ma keep dranking ‘til all the drank is gone (2009)

Available epidemiological evidence suggests that overall there was an expansion of OPR use nationwide during the late 1990s. During this period, use of many illicit substances other than marijuana and OPRs decreased significantly among teens. The Monitoring the Future survey indicates that lifetime use of heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine, ecstasy, LSD, alcohol, and cigarettes among 12th graders all decreased steadily throughout the 1990s (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2011). However, Figure 2 identifies how use of narcotics other than heroin increased among 12th graders during the late 1990s to a much higher level in the 2000s. Data from Monitoring the Future survey presented in Figure 2 strongly suggest that an expansion in OPR use among high school seniors was underway in 1994 or even earlier, and that a slowdown into plateau was evident by 2000.

FIGURE 2.

Past-year nonmedical OPR use among youths and young adults nationwide, MTF and NSDUH 1994–2010 (from Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2011, p.91). Note: NSDUH Data are presented for 1999 to 2001 because of design changes in the survey. These design changes preclude direct comparisons of estimates from 2002 to 2010 with estimates prior to 1999. Note: Data for MTF are for “narcotics other than heroin.” MTF estimates from 1994 to 2001 are not comparable with MTF estimates for 2002 and later due to questionnaire changes.

The most pressing indicator of upswings in OPR use is the rate at which users (including those OPR users with valid prescriptions) confront dependence, overdose, and death. One recent study indicated that 7% of 12 to 17 year olds reported non-prescribed OPR use in the past year, and that 7% of those reported symptoms of abuse (Wu, Ringwalt, Mannelli, & Patkar, 2008). Between 1998 and 2002, opiate painkiller mentions in deaths referred to medical examiners increased in 28 of the 31 reporting locations (Compton & Volkow, 2006a; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011) reported that prescription painkiller overdoses tripled between 1999 and 2008. The U.S. Drug Abuse Warning Network noted that emergency department visits related to opiates and opioids had increased 24%, and that methadone-related visits had increased 29% between 2004 and 2005 alone (McCarthy, 2007). The National Drug Threat Survey reports that 13.9% of the state and local law enforcement they surveyed reported that controlled prescription drugs were their greatest drug threat in 2010, increasing from 9.8% in 2009 (US Department of Justice 2010). Furthermore, 51% of state and local law enforcement agencies reported street gang involvement in diverted pharmaceuticals, increased from 49% in 2009 (US Department of Justice, 2011a). Similarly, an increasing number of these agencies reported increases in property and violent crime related to prescription OPR diversion between 2009 and 2010 (US Department of Justice, 2011).

A Plateau Reached?

As depicted in Figure 2, OPR use among youths and young adults saw a significant increase in the early 2000s and then held steady at approximately 9% among high school seniors and approximately 12% among slightly older young adults aged 18–25 years (Johnston et al., 2011). Figure 2 strongly suggests that the OPR Epidemic plateaued around 2000. However, this represents a nation-wide average that does not consider distinct regions or sociocultural and ethnic contexts, wherein the stage of the epidemic may vary considerably. This study analyzes a multi-city dataset to provide information about a geographically diverse group of locations and to discern whether the expansion phase has given way to plateau (or even decline) in at least some of the cities represented in the Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM) II dataset.

METHODS

Arrestee data provide information about drug use trends of great interest to public health, law enforcement, and other related service agencies. Heavy drug users are much better represented among arrestee samples than in general population studies (Golub & Johnson, 2002), and trends among arrestees often parallel (or are at the forefront of) trends in the general population. Accordingly, this article analyzes self-report of past 3-day OPR use by arrestees from 9 of the 10 geographically diverse locations served by the ADAM program during the 2000s. We use descriptive statistical procedures and logistic regression to identify patterns and trajectories in arrestee OPR use that illuminate variations in use among adult arrestees over time as well as by region, age, and race/ethnicity.

Sample

The Drug Use Forecasting program was established in 1987 by the National Institute of Justice (2003) to measure trends in illicit drug use among booked arrestees across a geographically diverse group of local jurisdictions. In 2000, the Drug Use Forecasting program underwent substantial improvement, especially with regard to obtaining a representative sample, and was renamed the ADAM Program (National Institute of Justice, 2003, 2004). The program was temporarily discontinued after 2003. In 2007, the ADAM program was reintroduced by the Office of National Drug Control Policy as the ADAM II program. The ADAM II program purposefully follows the same recruitment and interview procedures as its predecessor to maintain compatibility (Hunt & Rhodes, 2009; Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2009). ADAM II collects data from adult male arrestees at 10 geographically diverse locations: Atlanta, Georgia; Charlotte, North Carolina; Chicago, Illinois; Denver, Colorado; Indianapolis, Indiana; Manhattan, New York; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Portland, Oregon; Sacramento, California; and Washington, DC. Participants are offered a small incentive (e.g., a candy bar) for participation, and participation rates are generally strong. From 2000 to 2010, 75% to 86% of selected respondents who were available agreed to participate in a 20 to 25 minute survey.

This analysis uses the public use data available from the National Archive of Criminal Justice Data for ADAM covering 2000-2003 and for ADAM II covering 2007–2010. Because of the gap between the ADAM and ADAM II programs, no data are available for 3 years (2004–2006). The current analysis focuses on the 41,501 adult male arrestees aged 18 years and older who participated in the ADAM program at one of the ADAM II locations other than Washington, DC. Approximately one-quarter as many arrestees were interviewed in Washington, DC as they were at other locations, which precluded reliable estimates of OPR prevalence rates among youthful adult arrestees, so that location was excluded from data analysis.

One of the greatest advantages of the ADAM program is that it obtains an urinalysis, which is used to obtain an objective measure of recent drug use. Unfortunately, these measures could not be used for the study of OPR use. In a preliminary analysis, we determined that only about one-quarter of arrestees who reported use of opiate-based painkillers in the past 3 days were detected as recent opiate users according to the Enzyme multiplied imminoassy technique (EMIT) test used by the ADAM program. In contrast, the rate of detection for self-reported heroin use was 89%. There are numerous reasons for this possible discrepancy, including low opiate levels in painkillers, synthetic versus natural compounds, and frequency and quantity of use. Because of these inaccuracies in urinalysis with regard to OPR use, the current study examines self-report data. This likely represents a serious undercount of OPR use. Prior studies of the ADAM data have found that that typically about half of detected opiate users self-report use (Golub, Johnson, Taylor, & Liberty, 2002; Harrison, Martin, Enev, & Harrington, 2007; Lu, Taylor, & Riley, 2001).

Measure

The ADAM II questionnaire asks the following:

Now I’d like to ask you about your use of other drugs, including prescription drugs. As I read down the list, please tell me if you used any of these drugs in the past 3 days. In the past 3 days, did you use any: … e) Any of the following painkillers: Codeine, Dilaudid, Vicodin, OxyContin, or Percocet; … g) Demerol, Fentanyl. (Hunt & Rhodes, 2010, unit MU361)

For the purposes of the analyses that follow, all of the above OPRs were treated together. Fentanyl and Demerol, both pure synthetic opioids, were considered for separate analyses, but the low rates of their use limited the analytic value of disaggregation. Importantly, the ADAM II questionnaire does not ask whether arrestees have prescriptions for the OPRs they report using. This is a limitation of the ADAM program’s data. Accordingly, the outcome variable in this research is OPR use rather than misuse or abuse.

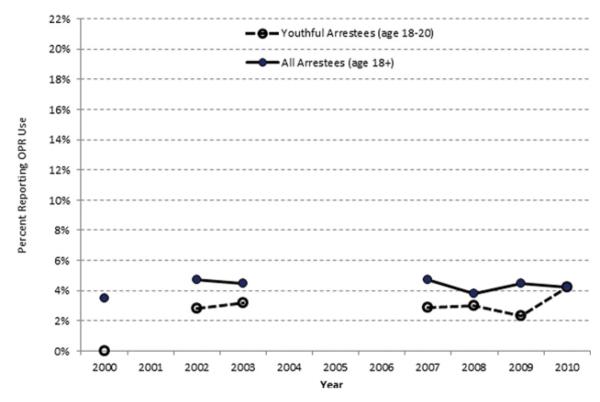

Graphical Trend Analysis

A graphical trend analysis was used to identify the timing of transitions between phases of the OPR Epidemic at each of nine ADAM II locations studied. The four phases of the drug epidemic can be distinguished from a graph similar to Figure 1 showing the trend in use of a drug over time. Figure 1 serves as a roadmap of what to expect over the natural course of a drug epidemic. During the expansion phase, the prevalence in use of a drug increases dramatically. The expansion phase can be distinguished from the plateau phase by visual inspection. During the plateau phase, use of a drug remains relatively constant at a high level, as shown in Figure 2. The start of the decline phase is more difficult to identify from the overall trend in use. This is because the shift occurring at this point primarily affects youths and may have a limited effect on older existing users. Accordingly, the graphical trend analysis also examines use among arrestees aged 18 to 20 years. The decline phase can be distinguished by a sharply decreasing prevalence of use among these youthful adult arrestees.

There are several other factors that can affect the prevalence estimated in any year, including policing priorities, changes in supply, and random chance. This is particularly a problem with regard to estimates of OPR use among youthful adult arrestees. On average, there were 75 arrestees aged 18 to 20 years at each location in each year, and often as few as 50. The unweighted standard error (SE) for a prevalence rate is calculated according to the following formula: SE = [P(1-P)/N]½. A minimum sample size (N) of 50 cases and a typical OPR prevalence rate (P) of 10% assures a maximum SE of 4.2%. Accordingly, in reading the graphs, limited credence was given to single-year changes in prevalence among youthful adult arrestees of less than 8.4% (this margin of error of twice the SE corresponds with an approximate 95% confidence interval) unless rates were comparably high in successive years. Generally, we looked for changes that were sustained across 2 or 3 years. The overall rate of use among all adult arrestees was generally more reliable because the sample sizes were typically larger than 500 participants. A minimum sample of 500 participants assures a maximum SE of 1.3%, for which the appropriate margin of error is 2.6%.

Logistic Regression Analysis

Logistic regression was used to identify significant variations across interview year, birth year, and race and ethnicity, as well as arrest charge and charge severity. Logistic regression has the important property of estimating the variation associated with each independent variable simultaneously and thereby controlling for the influence of all other variables included in the analysis (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 2000). In this manner, it was possible to estimate how much detected use varied across birth years controlling for policing priorities that could be identified by a difference in the mix of arrestees and arrest charges, variations across race and ethnicity, and any other factors that could affect year-to-year variation. The Wald statistic was used to test whether the variation associated with each independent variable was statistically significant. This statistic also provides a rough indication of the relative importance of each factor, net of all other variables included in the model. In this manner, the regression model was able to approximate how much more the variation in detected drug use was associated with birth year than with interview year, race or ethnicity, arrest charge, and charge severity.

Logistic regression models show how the odds of detected use vary systematically across arrestees. Odds are an alternative method for expressing the probability (P) or percentage of arrestees having a characteristic (e.g., reported OPR use). The formula for calculating odds is as follows: Odds = P/(1-P). Logistic regression represents the systematic variation as odds ratios (ORs). By convention, a parameter value of 1.0 is associated with the reference category for each variable. For example, 1975–1979 was selected as the reference category for birth year. Logistic regression provided an estimated for how use differed with birth year. For example, the parameter associated with 1990 identified the extent that arrestees in 1990 were more (or less) likely to report use. An estimate of 2.0 would indicate that arrestees born in 1990 were twice as likely (had twice the odds) of being users than those born in 1975–1979. A parameter estimate below 1.0 would indicate that a group was less likely to have used.

RESULTS

This section examines OPR use among adult arrestees (aged 18 years and older) at nine locations served by the ADAM II program. Figure 3 reveals substantial regional variation in OPR use by arrestees as of 2010. Use was most common at two West Coast locations (Portland and Sacramento) and one Midwest location (Minneapolis). OPR use was about half as common or less in Denver, other Midwest locations, and at Eastern locations. Table 1 presents the results of the logistic regression analyses. The parameter estimates associated with interview year and birth year are used to confirm the course of the drug epidemic at each location and are described along with the graphical trend analyses later in this section. Drug charge proved statistically significant at only one location (Indianapolis), but the variation was only marginally significant (at α = .05 but not the more rigorous α = .01 level). Charge severity was not significant in any of the models. From this data, we concluded that OPR use generally does not tend to vary among arrestees based on charge type or severity.

FIGURE 3.

Variation in OPR use among ADAM II arrestees across locations.

TABLE 1.

Multivariate Analysis (Logistic Regression) of Variation in Reported Past 3-day Use of Opiate Painkillers using Data from the Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring Program, 2000–2010

| Odds ratio (Wald Statistic) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| West |

Midwest |

Northeast |

Southeast | ||||||

| Portland | Sacramento | Denver | Minneapolis | Indianapolis | Chicago | Manhattan | Charlotte | Atlanta | |

| Interview year | (29.0)** | (7.6) | (15.7)* | (24.4)** | (50.8)** | (9.5) | (50.5)** | (9.4) | (1.9) |

| 2000a | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | — | 1.0 | — | — |

| 2001 | 1.5 | — | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.0 | — | 0.9 | — | — |

| 2002 | 1.6 | — | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.6 | — | 1.0 | — | — |

| 2003 | 2.1 | — | 1.3 | 2.0 | 1.1 | — | 1.4 | — | — |

| 2007 | 2.6 | — | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.2 | — | 3.0 | — | — |

| 2008 | 1.9 | — | 1.8 | 2.4 | 1.5 | — | 1.8 | — | — |

| 2009 | 2.3 | — | 1.6 | 2.8 | 2.2 | — | 3.4 | — | — |

| 2010 | 2.2 | — | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.7 | — | 3.6 | — | — |

| Birth Year | (20.2) | (28.4)* | (31.2)* | (34.6)** | (11.6) | (20.0) | (35.5)** | (7.3) | (8.3) |

| <1960 | — | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.6 | — | — | 2.3 | — | — |

| 1960–64 | — | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.4 | — | — | 2.2 | — | — |

| 1965–69 | — | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.0 | — | — | 1.3 | — | — |

| 1970–74 | — | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.5 | — | — | 1.5 | — | — |

| 1975–79a | — | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | — | — | 1.0 | — | — |

| 1980 | — | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | — | — | 0.9 | — | — |

| 1981 | — | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.0 | — | — | 0.4 | — | — |

| 1982 | — | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.6 | — | — | 1.1 | — | — |

| 1983 | — | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.5 | — | — | 0.7 | — | — |

| 1984 | — | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | — | — | 0.4 | — | — |

| 1985 | — | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.2 | — | — | 0.6 | — | — |

| 1986 | — | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.0 | — | — | 0.8 | — | — |

| 1987 | — | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0.8 | — | — | 1.3 | — | — |

| 1988 | — | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.3 | — | — | 0.8 | — | — |

| 1989 | — | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.6 | — | — | 0.9 | — | — |

| 1990 | — | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.9 | — | — | 0.6 | — | — |

| 1991 | — | 1.3 | 0.4 | 1.3 | — | — | 0.7 | — | — |

| 1992 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.8 | — | — |

| Race/ethnicity | (12.8)** | (3.4) | (7.7) | (36.4)** | (74.3)** | (49.1)** | (12.6)** | (84.8)** | (18.0)** |

| African Americana |

1.0 | — | — | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| White | 1.1 | — | — | 2.4 | 2.0 | 5.2 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 1.9 |

| Hispanic | 1.2 | — | — | 1.1 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 2.2 |

| Other/missing | 0.6 | — | — | 0.9 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Arrest charge | (7.2) | (3.0) | (0.5) | (2.9) | (8.6)* | (0.3) | (5.1) | (6.2) | (3.1) |

| Drugsa | — | — | — | — | 1.0 | — | — | — | — |

| Violent | — | — | — | — | 1.2 | — | — | — | — |

| Income | — | — | — | — | 1.1 | — | — | — | — |

| Other | — | — | — | — | 0.8 | — | — | — | — |

| Charge severity | (1.6) | (3.2) | (4.1) | (1.1) | (4.5) | (2.3) | (2.0) | (5.8) | (0.5) |

| Felonya | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Misdemeanor | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Other | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Base odds | .09 | .11 | .04 | .04 | .07 | .02 | .02 | .05 | .03 |

Reference Category

Parameter estimates not shown because variation with this variable was not statistically significant.

Statistically significant at the α = .05 level.

Statistically significant at the α = .01 level.

Variation with Race or Ethnicity

Findings demonstrated that OPR use among African American and Hispanic subpopulations differed by geographical location. There was substantial variation in OPR use with race/ethnicity at seven of nine locations. In the Midwest, Northeast, and Southeast, OPR use was typically about twice as common among White arrestees than among African Americans, except in Chicago where it was five times more common. The prevalence among Hispanics was closer to the rate among Whites than African Americans at four locations (Indianapolis, Chicago, Charlotte, and Atlanta) and closer to the rate for African Americans at two locations (Minneapolis and Manhattan). In contrast, in Western locations the rates among White, African American, and Hispanic arrestees were similar.

WEST

Portland: Plateau

OPR use among arrestees in Portland increased from 7% in 2000 to 13% in 2003 ( Figure 4 ). From 2007 to 2010, the prevalence was approximately 14%, with a 1-year decrease to 11% in 2008. Because the 1-year decrease was relatively modest and did not persist into a 2009, we attributed this fluctuation to random chance as opposed to it being part of any larger trend. This trend through expansion into plateau is confirmed in the variation associated with interview year in Table 1, which indicates a steady and statistically significant increase in OPR use from an OR of 1.0 in 2000 to 2.6 in 2007. Because no data are available from 2004 to 2006, it is unclear as to the exact year that the OPR Epidemic entered the plateau phase. However, the data suggest that the expansion phase likely ended in 2003 because the rate in 2003 is close to the rates observed 2007–2010 and even higher than the rate in 2008. Figure 4 indicates a modest decline in OPR use in 2009 followed by a larger decline in 2010. This drop in use among youthful adult arrestees is consistent with the possibility that the OPR Epidemic could have entered the decline phase in 2009. However, Table 1 indicates that the variation across birth years was not statistically significant, which suggests that this apparent decline could be the result of a random fluctuation. Accordingly, we would wish to see additional data before declaring that the OPR Epidemic had entered a decline phase in Portland.

FIGURE 4.

Portland (OR): Reported use of opiate painkillers in past 3 days, ADAM 2000–10 (color figure available online).

Sacramento: Plateau

The data suggest that the OPR Epidemic in Sacramento had already been in the plateau phase by 2000 ( Figure 5 ). The prevalence of use fluctuated from 10% to 15% from 2000 through 2010. The stability of this plateau phase is confirmed by the lack of statistically significant variation across interview years identified in Table 1. There was some variation across birth years. However, this variation was only marginally significant, and there was no clear pattern to the variation.

FIGURE 5.

Scaramento: Reported use of opiate painkillers in past 3 days, ADAM 2000–10 (color figure available online).

Denver: Decline

The variation in OPR use among arrestees in Denver does not neatly fit the predictions of the drug epidemic model ( Figure 6 ). As opposed to a rapid and substantial expansion phase, Denver experienced a modest jump from 6% in 2001–2003 to 8% in 2007. This variation is reflected in a marginally significant variation across interview years (Table 1). Figure 6 shows a decrease in use among youthful arrestees from 8% in 2007 to 3% in 2009-2010. Of note, there had been a previous decline from 4% in 2001 to 0% in 2003. Table 1 indicates that the variation across birth years is only marginally significant. We conclude that the OPR Epidemic was never particularly widespread in Denver, and that it entered a decline phase beginning in 2008.

FIGURE 6.

Denver: Reported use of opiate painkillers in past 3 days, ADAM 2000–10 (color figure available online).

Midwest

Minneapolis: Plateau

Minneapolis shows a clear expansion in OPR use from 2000 to 2002 ( Figure 7 ), after which it entered a plateau phase. Table 1 confirms that there was a statistically significant increase across interview years. Figure 7 presents some evidence consistent with the possibility that the OPR Epidemic entered a decline in 2009, but there is other substantial evidence to suggest discounting this possible trend. The prevalence of OPR use decreased substantially from 14% in 2008 to 6% in 2010. However, the rate among youthful adult arrestees of 14% in 2008 was substantially above the rate among all arrestees of 10%. This suggests that the high level of OPR use among youthful arrestees in 2008 may have been due to random chance. Furthermore, the decline from 2009 to 2010 mirrored a decline among all arrestees, indicating that the decline in OPR use among youthful adult arrestees may have been due to broader contextual trends such as a decline in availability or a change in policing priorities. Lastly, the prevalence of OPR use among youthful adult arrestees in 2010 is about the same as it is among all adult arrestees. During the decline phase, the rate of use among youthful adult arrestees is expected to decrease significantly below the rate prevailing among the broader arrestee population. Accordingly, we identified the OPR Epidemic among arrestees in Minneapolis to be in a plateau as of 2010.

FIGURE 7.

Minneapolis: Reported use of opiate painkillers in past 3 days ADAM 2000–10 (color figure available online).

Indianapolis: Plateau

Figure 8 shows that the increase in OPR use in Indianapolis came in sporadic jumps as opposed to the continuous increases elsewhere observed during the expansion phase. However, there was a substantial increase in OPR use from 8% in 2000 to twice that amount in 2010. Given the plateau observed at 11% to 14% during 2007– 2009, we estimate that the plateau phase was reached somewhere during 2004 to 2006, when no data was collected, but most likely in 2006. Table 1 confirms that there was a significant increase in OPR use from 2000 to 2007. Figure 8 shows a moderate 2-year decrease in OPR use among youthful adult arrestees from 12% in 2007 to 8% in 2009. However, this decline was followed by an increase back to 12% in 2010. Moreover, the variation across birth years in Table 1 was not statistically significant. Accordingly, we estimated that by 2010 the OPR Epidemic was still in plateau in Indianapolis.

FIGURE 8.

Indianapolis: Reported use of opiate painkillers in past 3 days, ADAM 2000–10 (color figure available online).

Chicago: No Epidemic

Figure 9 shows a moderate fluctuation in OPR use among arrestees between 3% and 7% from 2000 to 2010. Table 1 indicates that there were no substantial changes in prevalence over time or across birth years. This type of a stable pattern is characteristic of both the plateau phase of an epidemic and the incubation phase. Because of the relatively low prevalence of use in Chicago, particularly compared with other locations, we estimated that OPR use had not entered an epidemic in Chicago as of 2010. We distinguish this level of use as no epidemic as opposed to being in the incubation phase. Because of the existence of OPR use in Chicago, there is the potential that an OPR Epidemic could break out. However, it is also possible that Chicago will never experience a broader epidemic with widespread use of OPRs.

FIGURE 9.

Chicago: Reported use of opiate painkillers in past 3 days, ADAM 2000–10 (color figure available online).

Northeast

Manhattan: Plateau

Figure 10 indicates that the OPR Epidemic in Manhattan was still in its incubation phase in 2000–2003, with reported use rates of 2% to 3% among all arrestees and only 0% to 1% among youthful adult arrestees. By 2007, the prevalence had increased to 6%, where it remained through 2010, with a 1-year decrease to 3% in 2008. This increase was substantiated by statistically significant variation in the logistic regression model reported in Table 1. We estimate that the OPR Epidemic went through its expansion phase during 2004–2006, the period for which there is no data. We estimate that the OPR Epidemic reached the plateau phase around 2006.

FIGURE 10.

Manhattan: Reported use of opiate painkillers in past 3 days, ADAM 2000–10 (color figure available online).

Southeast

Charlotte: Plateau

Figure 11 indicates that OPR use had been relatively constant at 5% to 7% in 2000–2003. These same rates prevailed in 2008–2009. However, there was an anomalous 1-year peak at 10%, which we attribute to random chance. There was a substantial 1-year decrease in OPR use among youthful adult arrestees from 8% to 2% in 2010. This decline is consistent with expectations for the beginning of the decline phase. However, because this is a 1-year decline, it would be premature to estimate that the OPR Epidemic among arrestees in Charlotte had entered the decline phase. In addition, the logistic regression analysis in Table 1 indicates that there were no significant variations in OPR use across interview or birth years. This statistical finding is consistent with the possibility that the OPR Epidemic was in its plateau phase in Charlotte throughout 2000–2010.

FIGURE 11.

Charlotte: Reported use of opiate painkillers in past 3 days, ADAM 2000–10 (color figure available online).

Atlanta: No Epidemic

Figure 12 shows virtually no variation in OPR use, with a steady and low 4% to 5% rate among arrestees from 2000 to 2010. Table 1 indicates that there were no substantial changes in prevalence over time or across birth years. This stable pattern is characteristic of both the plateau and the incubation phase. Because of the relatively low prevalence of use, we estimated that OPR use had not entered an epidemic in Atlanta as of 2010.

FIGURE 12.

Atlanta: Reported use of opiate painkillers in past 3 days, ADAM 2000–10 (color figure available online).

DISCUSSION

Analyses of OPR trends during the 2000s in the nine locations reveal several important aspects of the OPR Epidemic in the United States. First, there was strong regional variation in OPR use among arrestees. Cities such as Manhattan demonstrated extremely low rates of OPR use, especially during the latter half of the 2000s. In comparison, reported use in Minneapolis and Indianapolis confirm that the epidemic observed in the Appalachian states during the mid- to late-1990s (Tunnell, 2004) is of nationwide concern, at least with regard to individuals who are arrested. Similarly, high OPR use rates in Portland and Sacramento suggest that OPRs have expanded to California and the Pacific Northwest, even as East Coast cities, including Manhattan, Atlanta, and Washington, DC, showed much lower rates of use.

Demographic predictors of OPR use appear also to vary considerably by city and region. Being White has been identified as a risk factor for OPR misuse in extant research (Havens et al., 2007). The ADAM data indicate similar variation with race and ethnicity in the East and Midwest. However, in the two Western cities, race played no discernible role in rates of use. Hispanic ethnicity had an idiosyncratic relationship with OPR use. Use among Hispanic arrestees was similar to their White counterparts in four locations and to their African American counterparts in the other five. Notably, even in the Southeastern cities of Atlanta and Charlotte, African American arrestees reported less use of OPRs than Whites and Hispanics. Further research will be needed to determine the extent to which the celebration of codeine/promethazine syrup in Southern hip-hop music is emblematic of a drug use trend among youth that has spread beyond Louisiana and Texas. It may also be necessary to investigate the extent to which youth recognize sizzurp as an opiate painkiller and can accurately report on use of OPRs when taking surveys such as Monitoring the Future.

Despite these substantial variations in the OPR Epidemic across locations, the overall evidence suggests that OPR use among arrestees is not increasing in any of the nine locations studied. Table 2 summarizes the state of the OPR Epidemic as of 2010 by location. By 2010, a substantial OPR Epidemic among arrestees had not yet materialized at two locations (Chicago and Atlanta), was in plateau at another five, (Sacramento, Minneapolis, Indianapolis, Manhattan, Charlotte), and may have entered a decline at two (Portland and Denver). This finding has important policy implications for those seeking to create sensitive and timely interventions. During the plateau phase of a drug epidemic, the goal is to move the epidemic into decline through prevention programs that may establish anti-use norms among youths. Further research into adolescent OPR abuse will need to examine the trajectories of substance use that lead to OPR abuse and the correlates and pathways that characterize progression from casual or medically authorized use to illicit, problematic forms of use and abuse.

TABLE 2.

Timing of Major Changes in the Opiate Pain Reliever Epidemic from 2000–2010 by Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring II Location

| West |

Midwest |

Northeast |

Southeast |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portland | Sacramento | Denver | Minneapolis | Indianapolis | Chicago | Manhattan | Charlotte | Atlanta | |

| Shift from expansion to plateau |

2003 | <2000 | unclear | 2002 | ~2006 | — | ~2006 | <2000 | — |

| Shift from plateau to decline phase |

2009 | (?) | — | 2008 | — | — | — | — | — |

This study has several limitations. First, there is the 3-year gap between 2004 and 2006 during which no ADAM data were collected, which limited our ability to clearly establish the consistency of prevailing trends throughout the 2000s. Moreover, the analysis involves only those individuals who get in trouble with the law. Potentially the timing and certainly the intensity of the OPR Epidemic varied across subpopulations. The prevalence of recent use may have been lower among the general population of individuals at each location who do not tend to get arrested. However, the reviewed Monitoring the Future survey and the National Survey of Drug Use and Health data suggest that the rates of OPR use among youths in the general population are similar to those estimated among youthful adult arrestees in this analysis (Johnston et al., 2011). Furthermore, the ADAM program’s broad focus on OPR use, irrespective of whether that use involves a legitimate doctor’s prescription, serves to cluster licit and illicit use of the drug to the detriment of more detailed analyses of potential differences between these two user groups. Finally, the location of the ADAM programs in urban areas leaves open questions about how trends in OPR use may differ between rural and urban locations.

Despite these limitations, this study has provided a foundational analysis of OPR use in the United States among arrestees that demonstrates the ongoing importance of studying drug epidemics within carefully delimited populations. The prevailing OPR Epidemic appears to be highly diffuse and diverse in its regional and social constitution. Accordingly, it would appear to be important for criminal justice, drug abuse, and related decision makers to obtain location specific data and not to rely exclusively on aggregate trends in national data.

Footnotes

A blunt is an inexpensive cigar in which the tobacco is replaced with marijuana. Many youths, especially African Americans, prefer to smoke marijuana in a blunt as opposed to a joint or pipe. We use the term Marijuana/Blunts Epidemic to distinguish the more recent upsurge in marijuana use starting in the 1990s from the widespread marijuana use that prevailed in the 1960s and 1970s.

Lil Wayne “Me and My Drank” lyrics copied from MetroLyrics.com: http://www.metrolyrics.com/me-and-my-drank-lyrics-lil-wayne.html#ixzz1iJRQZvUM

NOTES

REFERENCES

- Anderson RM, May RM. Infectious diseases of humans: Dynamics and control. Oxford; Oxford, UK: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Becker HS. History, culture, and subjective experience: An exploration of the social bases of drug-induced experiences. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1967;8:163–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens DA, Caulkins JP, Tragler G, Feichtinger G. Why present-oriented societies undergo cycles of drug epidemics. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control. 2002;26:919–936. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett AS, Golub A. Sociological factors and addiction. In: Shaffer HJ, LaPlante DA, Nelson SE, editors. Addiction syndrome handbook. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2012. pp. 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E. New addiction on campus: Raiding the medicine cabinet. Wall Street Journal. 2008 Mar 24; Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB12063987711716075.html.

- Boyd CJ, McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Young A. Prescription drug abuse and diversion among adolescents in a southeast Michigan school district. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:276–281. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownstein HH. The media and the construction of random drug violence. Social Justice. 1991;18(4):85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vital signs: Prescription pain-killer overdoses in the US. Mobidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;60(43):1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Inciardi JA, Muñoz A. Trends in abuse of OxyContin® and other opioid analgesics in the United States: 2002-2004. The Journal of Pain. 2005;6:662–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GB, McAllister MS. Combating abuse and diversion of prescription opiate medications. Psychiatric Annals. 2006;36:410. [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Volkow ND. Abuse of prescription drugs and the risk of addiction. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006a;83:S4–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Volkow ND. Major increases in opioid analgesic abuse in the United States: concerns and strategies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006b;81:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis R. The improbably transformation of inner-city neighborhoods: Crime, violence, drugs and youth in the 1990s. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology. 1998;88:1233–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Forman RF. Availability of opioids on the Internet. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:889. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frayser Boy. I got dat drank. On Me being me. Wanner Brother/Asylum/Hypnotize Minds Records; Los Angels, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RA. The changing face of teenage drug abuse—the trend toward prescription drugs. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354:1448–1450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furst RT, Johnson BD, Dunlap E, Curtis R. The stigmatized image of the crack head: A sociocultural exploration of a barrier to cocaine smoking among a cohort of youth in New York City. Deviant Behavior. 1999;20:153–181. [Google Scholar]

- Gfroerer J, Penne M, Pemberton M, Folsom R. Substance abuse treatment need among older adults in 2020: The impact of the aging baby-boom cohort. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A. The cultural/subcultural contexts of marijuana use at the turn of the twenty-first century. Haworth; Binghamton, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD. A recent decline in cocaine use among youthful arrestees in Manhattan (1987-1993) American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:1250–1254. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.8.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD. The crack epidemic: Empirical findings support a hypothesized diffusion of innovation process. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences. 1996;30:221–231. [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD. Crack’s decline: Some surprises across U.S. cities. National Institute of Justice Research in Brief. 1997;165707:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD. The rise of marijuana as the drug of choice among youthful adult arrestees. National Institute of Justice Research in Brief. 2001;187490:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD. The misuse of the “gateway theory” in U.S. policy on drug abuse control: A secondary analysis of the muddled deduction. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002;13(1):5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD. The new heroin users among Manhattan arrestees: Variations by race/ethnicity and mode of consumption. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2005;37:51–61. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2005.10399748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD, Dunlap E. Subcultural evolution and illicit drug use. Addiction Research & Theory. 2005;13:217–229. doi: 10.1080/16066350500053497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD, Dunlap E, Sifaneck S. Projecting and monitoring the life course of the marijuana/blunts generation. Journal of Drug Issues. 2004;34:361–388. doi: 10.1177/002204260403400206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD, Sifaneck S, Chesluk B, Parker H. Is the U.S. experiencing an incipient epidemic of hallucinogen use? Substance Use and Misuse. 2001;36:1699–1729. doi: 10.1081/ja-100107575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD, Taylor A, Liberty HJ. The validity of arrestees’ self-reports: Variations across questions and persons. Justice Quarterly. 2002;19:477–502. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid A. The developmental cycle of a drug epidemic: The cocaine smoking epidemic of 1981–1991. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1992;24:337–348. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1992.10471658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Gfroerer J, Colliver J. OAS Data Review. Office of Applied Studies (OAS), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA); Washington, DC: 2009. An examination of trends in illicit drug use among adults aged 50–59 in the United States; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison LD, Martin SS, Enev T, Harrington D. Comparing drug testing and self-report of drug use among youths and young adults in the general population. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman DM, Golub A. The social construction of the crack epidemic in the print media. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1999;31:423–433. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1999.10471772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens JR, Oser CB, Leukefeld CG, Webster JM, Martin SS, O’Connell DJ, et al. Differences in prevalence of prescription opiate misuse among rural and urban probationers. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:309–317. doi: 10.1080/00952990601175078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens JR, Walker R, Leukefeld CG. Prevalence of opioid analgesic injection among rural nonmedical opioid analgesic users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson G. Fentanyl-related deaths: Demographics, circumstances, and toxicology of 112 cases. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 1991;36(2):422–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd edition Wiley; New York, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt D, Rhodes W. Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring Program II in the United States, 2008: Technical documentation report. 2009 Retrieved from www.icpsr.umich.edu.

- Hunt D, Rhodes W. Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring Program II in the United States: 2009 Data Collection Instrument. ICPSR; Ann Arbor, MI: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LG, Chambers CD. The heroin epidemic: A study of heroin use in the US, 1965–1975 (Part II) Spectrum; Holliswood, New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins P. Synthetic panics: The symbolic politics of designer drugs. NYU Press; New York, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Golub A. Generational trends in heroin use and injection among arrestees in New York City. In: Musto D, editor. One hundred years of heroin. Auburn House; Westport, CT: 2002. pp. 91–128. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Golub A, Dunlap E. The rise and decline of drugs, drug markets, and violence in New York City. In: Blumstein A, Wallman J, editors. The crime drop in America. revised ed Cambridge; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 164–206. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD. Toward a theory of drug epidemics. In: Donohew DH, Sypher H, Bukoski W, editors. Persuasive communication and drug abuse prevention. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1991. pp. 93–132. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2010. Volume I: Secondary school students. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, Michigan: 2011. p. 744. [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. What you been drankin’ on? On Harlem: Diary of a summer. Koch/eOne Records; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jones RG. Heroin’s hold on the young. New York Times. 2008 Jan 13; Retrieved from http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9803EFD81F3CF930A25752C0A96E9C8B63&scp=2&sq=Heroin’s+Hold+on+the+Young&st=nyt.

- Jonnes J. Hip to be high: Heroin and popular culture in the Twentieth Century. In: Musto DF, editor. One hundred years of heroin. Auburn House; Westport, CT: 2002. pp. 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Katz E, Levin ML, Hamilton H. Traditions of research on the diffusion of innovation. American Sociological Review. 1963;28:237–252. [Google Scholar]

- Lankenau SE, Teti M, Silva K, Jackson Bloom J, Harocopos A, Treese M. Initiation into prescription opioid misuse amongst young injection drug users. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2011;23:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinwand D. Prescription drugs find place in teen culture. USA Today. 2006 Jun 12; Retrieved from http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2006-06-12-teens-pharm-drugs_x.htm.

- Lessenger JE, Feinberg SD. Abuse of prescription and over-the-counter medications. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2008;21(1):45–54. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.01.070071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lil Wayne, Short Dawg. Me and my drank. On Lil Wayne—Young money empire part 3. White Owl Drop That Records; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lineberry TW, Bostwick JM. Taking the physician out of “physician shopping”: A case series of clinical problems associated with Internet purchases of medication. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2004;79(8):1031–1034. doi: 10.4065/79.8.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu NT, Taylor BG, Riley KJ. The validity of adult arrestee self-reports of crack cocaine use. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27:399–419. doi: 10.1081/ada-100104509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann L. Top ten songs about ingesting cough syrup for leisure. 2011 Jul 20; Retrieved from http://blogs.dallasobserver.com/dc9/2011/07/listomania_top_ten_songs_about.php.

- McCarthy M. Prescription drug abuse up sharply in the USA. Lancet. 2007;369:1505–1506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60690-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean S, Bruno R. Harm reduction by syringe filters: A cost-effective means of improving the health of injecting drug users. Australian National Drug Strategy; Canberra, Australia: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Musto D. The rise and fall of epidemics: Learning from history. In: Edwards G, Strang J, Jaffe JH, editors. Drugs, Alcohol, and Tobacco: Making the Science and Policy Connections. Oxford; New York: 1993. pp. 278–284. [Google Scholar]

- Musto DF. The American disease: Origins of narcotic control. Oxford University Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Justice . 2000 Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring: Annual report. U.S. Department of Justice; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Justice Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM) Program in the United States, 2003: Codebook, data collection instruments, and other documentation. 2004 Retrieved from www.icpsr.umich.edu.

- Office of National Drug Control Policy ADAM II: 2008 annual report. 2009 Retrieved from www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov.

- Peters J, R J, Kelder SH, Markham CM, Yacoubian J, G S, Peters LCA, Ellis A. Beliefs and social norms about codeine and promethazine hydrochloride cough syrup (CPHCS) onset and perceived addiction among urban Houstonian adolescents: an addiction trend in the city of lean. Journal of drug education. 2003;33:415–425. doi: 10.2190/NXJ6-U60J-XTY0-09MP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinarman C, Levine HG. Crack in America: Demon drugs and social justice. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovation. 4th edition Free Press; New York, NY: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer J. Down on the pharm, again: Debunking “pharm parties” for the third time. Slate. 2008 Mar 25; Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/press_box/2008/03/down_on_the_pharm_again.single.html#pagebreak_anchor_2.

- Siegel B. On The b.Coming. Def Jam Records; New York, NY: 2005. Purple rain. [Google Scholar]

- Sifaneck SJ, Kaplan CD, Dunlap E, Johnson BD. Blunts and blowtjes: Cannabis use practices in two cultural settings and their implications for secondary prevention. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology. 2003;31:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Slim Thug. On Boss of all bosses. Koch/eOne Records; New York, NY: 2009. Learnin’. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (SAMHSA) Overview of findings from the 2003 National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Department of Health and Human Service, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administrative, Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tunnell KD. Cultural constructions of the Hillbilly Heroin and crime problem. In: Ferrell J, Hayward K, Morrison W, Presdee M, editors. Cultural criminology unleashed. Glass House; London: 2004. pp. 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Justice . National drug threat assessment. National Drug Intelligence Center (NDIC); Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Justice . National drug threat assessment. National Drug Intelligence Center (NDIC); Washington, DC: 2011a. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Justice . Drug Alert Watch. National Drug Intelligence Center (NDIC); Johnstown, PA: 2011b. Resurgence in Abuse of ‘Purple Drank’ (EWS Report 000008) pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler D, Caulkins JP, Behrens DA, Tragler G. Estimating the relative efficiency of various forms of prevention at different stages of a drug epidemic. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences. 2004;38:43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Ringwalt CL, Mannelli P, Patkar AA. Prescription pain reliever abuse and dependence among adolescents: a nationally representative study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:1020–1029. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31817eed4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, Havens JR, Leukefeld CG. Route of administration for illicit prescription opioids: A comparison of rural and urban drug users. Harm Reduction Journal. 2010;7:24. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-7-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Z-Ro . On Cocaine. Rap-A-Lot Records; Houston, TX: 2009. Can’t leave drank alone. [Google Scholar]