“Much of life can be understood in rational terms if expressed in the language of chemistry. It is an international language, a language for all of time, and a language that explains where we came from, what we are, and where the physical world will allow us to go. Chemical language has great esthetic beauty and links the physical sciences to the biological sciences.” from the “Two Cultures”

by Arthur Kornberg 1

On the special occasion of the awarding of the Tetrahedron Prize, I have been asked to provide an article on our research. In keeping with custom, this will start with some autobiographical background and proceed with an overview of some research conducted by my coworkers and collaborators. At the outset, I wish to acknowledge the many mentors, students, colleagues, family and friends who have figured and continue to figure in this journey. I have had and continue to have the good fortune of working with exceptional coworkers, over 300 and counting including over 70 now in academic positions around the globe and many others in leading positions in industry including directors, VPs and CEOs. While only some of their projects can be presented here and those at best in abbreviated form, the topics are more fully developed in the referenced primary literature from our laboratory and in references cited therein to noteworthy contributions from other laboratories. Additional contributions from several remarkable friends and scientists whose work is a source of continuing inspiration follow in this issue. I have benefited greatly from many teachers and have had the special benefit and pleasure of conducting research with and being mentored by Bill Stine (Wilkes), Fred Ziegler (Yale) and Gilbert Stork (Columbia). Each has generously shared special insights on chemistry, science and education and each has profoundly influenced my career. They are remarkable. My wonderful colleagues at Harvard and now at Stanford have also figured significantly in shaping our research program and its vision. Of special significance is Jacqueline Bryan Wender, a partner in life, whose wisdom, vision, style, and grace have been and continue to be a source of exceptional inspiration.

Like many fascinated with space travel at the time, I spent much of my childhood literally doing “research” on rocket fuels and testing their capacity to propel designed model rockets into “space” in the hills around my home. Some exploded, some burned, but many worked amazingly well. My transition from this “October Sky”2 world of model rockets and dreams to the excitement of undergraduate research was guided by Bill Stine. His patience in the laboratory, enthusiasm for science and breadth of interests from piloting planes to competitive tennis, made for extraordinarily diverse and rich learning experiences. Flying in his plane to Syracuse University to record NMR spectra on compounds we made is one of many unforgettable “research” experiences. It was Bill who encouraged me to think more broadly about chemistry and who with his colleagues at Wilkes put me on the path to graduate school. I arrived at Yale for graduate studies with an interest in biophysical chemistry but found on meeting with faculty that most research programs, whether focused on photochemistry, biosynthesis, mechanistic chemistry, biochemistry or spectroscopy, were heavily involved with and often slowed by problems with making molecules of interest. The message here was clear: if one could learn how to make molecules more quickly and efficiently one would have more time to spend on their study. I knew too little then to understand the broader ramifications of this perception but, as partly elaborated herein, it has indeed been a career long theme taking the form some years later of “step and time economy” and “function oriented synthesis” directed at “the ideal synthesis”,3 a goal we defined in 1985 in a form that most would agree with today: “ideal syntheses [are] those in which the target molecule is assembled from readily available starting materials in one simple, safe, economical, and efficient operation.”4

Learning to make molecules thus became the immediate focus of my graduate studies and Fred Ziegler provided the exceptional expertise to make that happen. His group was dynamic and intensely interactive, adding greatly to the learning experience and serving as a model for my own group’s operation a few years later. Most days at Yale were rich with discussions about problems and ideas. It was there that I also found time to scour the literature not for some homework assignment but simply to treat myself to what I considered then and now “recreational reading”. It was there that I first read about arene-alkene photo-cycloadditions, processes unrelated to my PhD research that later would figure significantly in the start of my own independent research.5 It was there that I also learned about cuprate chemistry, an experience that would years later figure in my group’s introduction of a new family of reagents, organobiscuprates.6 It was there that I also first explored the fascinating prototropic rearrangement of imines, again unrelated to my research but a subject that was to figure in my own independent research.7 At Yale, I had the pleasure of conducting a “methods” project8 and also completing the first total synthesis of a sesquiterpene by the name of eremophilone9. The former in retrospect was an exceptional test of laboratory technique as it required generating liquid HCN several times a week by the dropwise mixing of concentrated sulfuric acid and a saturated solution of NaCN and trapping the resultant bursts of HCN gas (bp = 26°C) in a cold trap. Coffee was not needed on those days. The eremophilone total synthesis elicited less adrenaline but was also rich with learning experiences and indeed provided my initial experimental introduction to organometallic chemistry and photochemistry. Some seeds were thus sown.

My plans for life-after-Yale, while long under consideration, were finalized with unanticipated speed. I had a discussion one morning with Fred Ziegler about possible postdoctoral positions and by the end of that morning Fred told me that Gilbert Stork had accepted me into his group. It was a great day. I arrived at Columbia University in September 1973, at which time Gilbert Stork proposed an exciting idea directed at the synthesis of reserpine. I was thus off exploring the world of heterocycle synthesis. This experience, not unlike my studies at Yale, was enhanced greatly by members of the Stork group and other groups at Columbia, and figured subsequently in projects pursued at the outset of my independent career, including a synthesis of reserpine, and continue to figure in a special collaboration on drug delivery research up to this very day. While I had NIH Postdoctoral Fellowship support for two years, my time with Gilbert Stork, while exceptional,10 was brief. Within weeks of my arrival at Columbia, I received a call from Robert Woodward asking if I would be interested in a faculty position at Harvard. My subsequent visit went well and was capped by a discussion with Woodward that started, after a full day of science and an evening meal, at 10 PM and ended the following morning around 7. I started at Harvard in July 1974.

At the outset of a journey it is often valuable to have a sense of where one is headed and, from a song of the period, “a code that one can live by”. The early view that emerged was simple. My interest in chemistry had always been fueled by its potential to address medical problems and that was now integrated with an interest in synthesis. This exciting fusion provided the path forward: advance synthesis and medicine by focusing on and studying molecules that might figure in the prevention, diagnosis or treatment of disease. The questions of which molecules to make and how to achieve clinical relevancy spawned some ideas and plans that remain central to our research even today and are touched upon herein.

At the outset of our independent research, while our synthetic interests focused on specific targets, the structures were selected based on their being representative of more general synthetic and biological problems. Both were important. As for the synthesis component of this fusion, a brief analysis of natural products revealed that while they differ in many ways, they can be universally categorized as acyclic and cyclic and the latter further organized as monocyclic and fused-, bridged- or spirocyclic with most having ring sizes between 3 and 16 members, and containing all carbon or carbon heteroatom compositions. No matter what the specific natural or non-natural target, it was a composite of one or more of these “general synthetic problems”. A check of the literature at the time revealed that methodology for the construction of rings of 7 or more members was not very advanced. In fact, the first syntheses of pseudoguaianes,11 5–7 ring systems with interesting biological activities, appeared only in 1976. More complex and more biologically important tiglianes, daphnanes and ingenanes had not been synthetically approached. Indeed the first member of this large triad of natural products families was not synthesized until many years later (1989).12 As we noted at the time: “the facile synthesis and further elaboration of functionalized bicyclo[5.3.0]decanes constitute an objective of considerable dimension in synthesis as suggested, in part, by the number and complexity of natural product families characterized by this subunit (e.g., pseudoguaiane, guaiane, daphnane, tigliane, ingenane, asebotoxin). The significance of this objective is further amplified by [their] potent and varied biological activity and, in particular, significant antitumor or cocarcinogenic activity.”13 And so the starting synthetic, biological and medicinal framework for our studies was put in place.

Our first independent studies were directed at the synthesis of spirocycles, seven-membered ring containing natural products, and medium ring containing natural products. While our introduction of the term “step economy” would come later, it was clear that our approaches were designed with that goal in mind.14 A method for constructing spirocycles using novel organobiscuprate reagents was designed to construct the key quaternary center in “only one synthetic operation” (Scheme 1).15 Our approach to seven-membered rings started with the introduction of a vinylcyclopropane (VCP) into a molecule that upon work up produced a divinylcyclopropane (DVCP), which upon distillative purification underwent a Cope rearrangement to give the seven-membered ring product (Scheme 2). As we noted at the time, “a particularly attractive feature of [this] method is that the entire annelation sequence can be performed in one synthetic operation, i.e., initial reaction (1,2 addition of the reagent), acidic workup (formation of the divinylcyclopropane), and distillation (rearrangement and purification).”16 This strategy for 7-membered ring synthesis subsequently figured in our syntheses of the pseudoguaianes damsinic acid and confertin, both additionally featuring a highly efficient CH activation process (Scheme 3).17 It also served as a gateway to the bigger synthetic challenges associated with more complex and more biologically important targets such as the tiglianes, daphnanes and ingenanes.18 The reader is referred to work from the groups of Marino19 and Piers20 for alternative, contemporaneous DVCP approaches to seven-membered rings.

Scheme 1.

Organo-bis-cuprates: New Reagents for a Single Step Spiroannelation

Scheme 2.

A Single Step Method for 7-membered Ring Synthesis based on a Divinylcyclopropane Rearrangement

Scheme 3.

An 11-step Synthesis of the Pseudoguaiane Damsinic Acid

Our concurrent studies on medium rings (i.e., 8-members and larger) borrowed on a concept that decades later in another form would dominate many facets of synthetic chemistry, namely the olefin metathesis reaction. When we initiated our research on this theme in the 1970s, there were no complex molecule studies involving the metathesis reaction and this no doubt reflected the limited capabilities of the catalysts at the time. Of conceptual importance, there was also some earlier debate about whether the metal catalyzed metathesis reaction proceeds in a pair-wise fashion or through a metal carbene. We saw the pair-wise mechanism as having special synthetic value. Given the limitations associated with the catalysts at the time and the potentially unique synthetic utility of a pair-wise cross metathesis, we sought to create a pair-wise metathesis process using what we called a photo-thermal olefin metathesis reaction (Scheme 4). While differing mechanistically from the now well studied metal catalyzed metathesis reaction, this pair-wise metathesis idea had its virtues as it allowed one to combine two simple, even commercially available cycloalkenes to produce added value medium ring products. Its use in the synthesis of the germacranolide isabelin (18), a cyclodecadiene, served to exemplify the utility of this concept for accessing targets that at the time were largely “unsolved” synthetic problems (Scheme 4). Our enthusiasm for this approach was reflected in the conclusion of the isabelin synthesis manuscript: “this (metathesis) strategy…should prove useful in establishing a general approach to germacradiene synthesis and in extending the metathesis concept to other natural and non-natural objectives”.21 It is interesting that the editor processing our first contribution22 suggested that we change the title because he felt no one would understand what a “metathetical route” might be. The pair-wise metathesis concept has been more recently beautifully deployed by White and coworkers in their synthesis of byssochlamic acids.23 Related work on what we call the photo-thermal metathesis reaction had also been reported by the groups of Lange, Wilson, Williams, and Mehta.24 A noteworthy additional aspect of our pair-wise metathesis studies is that the student who succeeded with this effort went on to become the CEO of Eli Lilly & Co.

Scheme 4.

A Photo-Thermal Olefin Metathesis Strategy: Total Synthesis of Isabelin

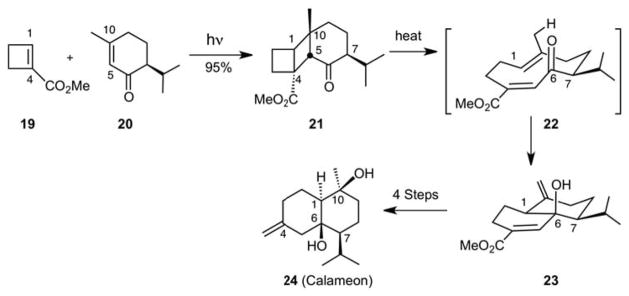

With step economical access to medium rings afforded by the photo-thermal metathesis reaction, the reservation about using medium rings as precursors for polycyclic targets was greatly reduced. For example, while computer based design at the time justifiably argued against designing approaches to bicyclics based on macrocyclic precursors due to the lack of easy access to the latter,25 the pair-wise crossed metathesis allowed for the two-step, one operation (photolysis followed by thermolysis) synthesis of such medium rings. Moreover, the resultant medium rings were strategically functionalized for transannular closure, a strategy used by Nature in polycycle assembly. Illustrative of this point, photolysis of piperitone and cyclobutene ester gave a crossed cycloadduct 21 in 95% yield based on piperitone (Scheme 5). Thermolysis of this cycloadduct afforded exclusively the trans-fused bicycle 23 in 95% yield through generation of a cyclodecadiene intermediate 22 followed by its transannular ene reaction closure. The ene product was converted in 5 steps to calameon (24), representing overall a 7 step, stereocontrolled route from simple common rings to bicyclic systems based on a transannular closure of a medium ring precursor.26 Reflecting its generality, this strategy also led to a concise 12-step synthesis of warburganal (27, Scheme 6) and access to other targets.27 A final point of significance is that in contrast to some perceptions about the practicality of photochemical reactions, the photochemical step in the photo-thermal olefin metathesis reaction can be conducted at high reactant concentrations (2.0 M) and on a multigram scale. Solvent, generally the greatest cause of atom loss in most reactions,28 is only needed in minor amounts to reduce the viscosity of the two reactants. Flow reactor photochemistry makes such processes even more practical.29

Scheme 5.

A Photo-Thermal Olefin Metathesis/Ene Cascade: Total Synthesis of Calameon.

Scheme 6.

Photo-Thermal Olefin Metathesis/Ene Sequence: Total Synthesis of Warburganal.

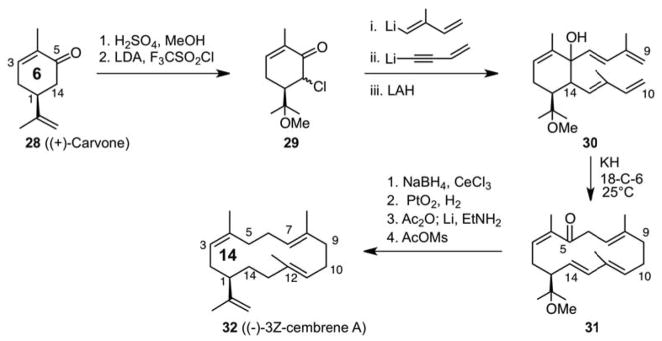

The photo-thermal olefin metathesis strategy for medium ring synthesis drives a ring expansion process through strain release involving the cycloreversion of a bicyclo[2.2.0]hexane. It provides a net four-atom expansion. At the time, this process and other ring expansion strategies were limited to expansions of 4 or fewer members. As such, the pool of commercially available common rings (5-, 6-, and 7-membered) could be parlayed only into 9-, 10-, and 11-membered rings. In considering how one might access larger rings from common rings, we developed a macroexpansion process involving an 8-atom ring expansion, thereby connecting the common rings to 13-, 14-, and 15-membered rings (Scheme 7). The concept, evolving from the observation that a Cope rearrangement expands a ring by 4-atoms through a [3.3] sigmatropic rearrangement, was based on the notion that an 8-atom expansion could arise from the “bis-vinylog” of the Cope process, namely a [5.5] sigmatropic rearrangement.30 Our study of this idea brought with it mechanistic questions about whether the [5.5] rearrangement proceeds actually through two consecutive [3.3] rearrangements and if so whether the latter [3.3] is an example of a charge (enolate) accelerated rearrangement.31 On the synthetic front, this concept allowed one to retrosynthetically connect medium ring targets to commercially-available, chiral-pool, common rings. The value of this connection is made clear in an 8-step synthesis of the 14-membered ring target, (−)-3-Z-cembrene A (32), starting from the commercially available 6-membered ring chiral precursor (+)-carvone (Scheme 7). This was the first route to cembranes based on ring expansion strategies. As noted at the time, this strategy represented a “fundamentally new approach to the preparation of chiral cembranoids and macrocycles from common ring precursors”.32 As emphasized in all of our target-oriented syntheses, the strategy has generality derived from step economy, providing a medium ring intermediate in only 4 steps and thus a “point of divergence” for accessing other members of the cembrane class. We also developed methodology for constructing dibutadienylcycloalkanes, a key to the general implementation of this concept, and illustrated its use in the synthesis of the 15-membered ring target muscone (35, Scheme 8).33

Scheme 7.

Macroexpansion Methodology: An 8-step Synthesis of 3Z-Cembrene A.

Scheme 8.

Macroexpansion Methodology: Synthesis of Muscone.

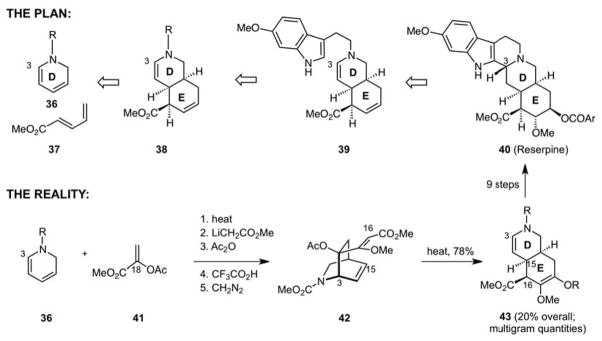

Concurrent efforts in our group to produce step economical access to the common heterocyclic systems were directed at cis-hydroisoquinolines, a problem encountered in the form of reserpine during my brief stay with Gilbert Stork. Departing completely from the intriguing plan proposed by Stork, and influenced as in the above noted work by the importance of step economy, our strategy was directed at effecting a Diels-Alder reaction between a dihydropyridine and pentadienyl ester with the expectation that under the thermal conditions of the cycloaddition reaction, the initially formed cycloadduct would convert to the cis-hydroisoquinoline through a Cope rearrangement (Scheme 9). It was an exciting idea but never realized. On the other hand, while requiring a few more steps (16 from pyridine), the plan ultimately led to one of the shortest syntheses of eserpine (40).34 An excellent comparative review of solutions to this synthetic problem from the labs of Woodward, Pearlman, Stork, Fraser- Reid, Liao, Hanessian, Mehta, Martin, Shea and our own has recently appeared.35

Scheme 9.

Diels-Alder/Cope Strategy for Hydroisoquinolines: 16-step Synthesis of Reserpine

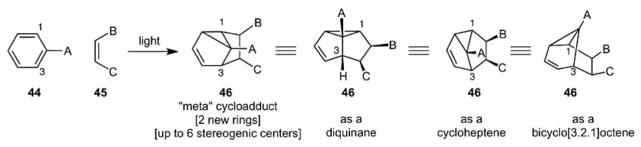

Drawing on some “recreational reading” done as a graduate student at Yale, another project activated for study in our lab at the time involved the arene-alkene photocycloaddition (Scheme 10). Discovered in 1966 by Bryce-Smith, Gilbert and Orger36 and by Wilzbach and Kaplan,37 and explored by Morrison,38 Srinivasan,39 and others,40 this reaction had largely been the focus of only photophysical and theoretical studies when we started. While unexplored in total synthesis at the time, it was clear that its capacity to convert simple starting materials into complex polycyclic products with up to 6 stereocenters was unique, even when judged against the complexity increase of the venerable Diels-Alder cycloaddition, a point that we emphasized in our first manuscript on this project. Adding further to the potential utility of this process in synthesis, it allows for a formal [3+2] cycloaddition to make 5-membered rings or, if the cycloadduct is processed differently, a [5+2] cycloaddition to make 7-membered rings or bicyclo[3.2.1]octane derivatives (Scheme 10). Aside from photophysical work, there was little known about factors that would control the regioselectivity, diastereoselectivity, and endo-exo selectivity of the process. Even less was known about how to deconvolute the cycloadducts to reach target polycycles although we recognized that the reaction “provides a cycloadduct which could serve as a precursor to a variety of synthetically important ring systems”.41 Again, the generality of the problem and potential generality of the solution provided the justification and motivation to explore this process.

Scheme 10.

The Arene-Alkene Meta-Photocycloaddition: A Unique, Complexity Increasing Strategy Level Reaction

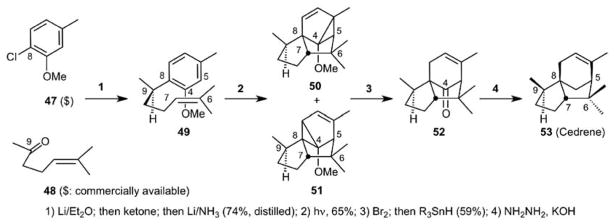

The importance of understanding the “rules” that govern selectivity cannot be overemphasized in a reaction that proceeds with a great complexity increase because non-selectivity manifests itself in product diversity. For example, in an intermolecular reaction between a trisubstituted arene and alkene with one stereocenter, up to 168 products could be formed if mode-, regio-, exo-endo and diastereoselectivity are not controlled. To address this formidable challenge but also broad opportunity, we elected to explore the use of this reaction in the synthesis of cedrene (53, Scheme 11).41 Our analysis (Scheme 12) was as follows and serves now as a mechanistic and selectivity template for the application of this reaction to any relevant target. Mode selectivity (1,3 vs, 1,2 vs 1,4) is governed by a difference in the ionization potential of the interacting species with 1,3 (or meta) cycloadditions favored when the difference is small. Of the meta adducts, only additions across activating alkyl and alkoxyl groups would be expected. The former would be disfavored in the cedrene approach, we reasoned, due to a syn pentane interaction. Exo/endo selectivity favors endo for intermolecular reactions, but our models indicated that exo would be preferred for the intramolecular process due to better orbital overlap. Finally, diastereoselectivity was expected to favor minimal interaction between the activating alkoxy group and the secondary methyl group. In the event, photolysis of arene-alkene 49 produced cycloadducts 50 and 51 in 65% yield. Both were converted together to cedrene (53) in two steps. Thus, this first exploration of the arene-alkene cycloaddition in total synthesis produced cedrene in only four synthetic operations from commercially available starting materials. As noted previously, we sought generality in our methods and this inaugural study now teed up the potentially general use of this process in the synthesis of 5- and 7-membered rings, bicyclo[3.3.0]octanes and bicyclo[3.2.1]octanes, as it defined how selectivities can be controlled (Scheme 12).

Scheme 11.

The Arene-Alkene Meta-Photocycloaddition: A 4-Step Synthesis of Cedrene

Scheme 12.

A Template for Selectivity Predictions in Arene-Alkene Photocycloadditions

For our group and many others, the connection between target relevant complexity (TRC) increase42 and step economy was again made clear in the cedrene synthesis: greater TRC increases generally correlate with greater step economy. This concept is evident in the step economy of subsequent total syntheses of numerous other natural as well as non-natural products based on the arene-alkene photocycloaddition, including a rather remarkable 3-step synthesis of the triquinane silphinene (58, Scheme 13)43 and a 3-step synthesis of novel-fenestranes44. The silphinene synthesis serves to reinforce and extend selectivity predictions made in the cedrene synthesis and clearly provides another demonstration of the striking correlation of complexity increase and step economy: the greater the increase in target relevant complexity per step, the shorter the synthesis.

Scheme 13.

The Arene-Alkene Meta-Photocycloaddition: A 3-Step Synthesis of Silphinene

In the silphinene study from 1985, we capture a view of the ideal synthesis that we have articulated and advanced for decades45, 46, 47, 48:

“Notwithstanding the major advances and impressive efficacy of contemporary synthesis, a considerable gap exists between current realities and the routine realization of ideal syntheses, i.e., those in which the target molecule is assembled from readily available starting materials in one simple, safe, economical, and efficient operation. The discovery or design and development of strategy level reactions figure significantly in reducing this disparity, particularly in the case of those transformations which allow for a great increase in structural complexity since the judicious use of such processes invariably results in a decrease in the number of operations needed to convert simple starting materials to complex targets.”43

This view evolved to include a more explicit sensitivity to time (economy) and the environment, goals now of unsurpassed contemporary importance in synthesis. “An ideal (the ultimate practical) synthesis is generally regarded as one in which the target molecule (natural or designed) is prepared from readily available, inexpensive starting materials in one simple, safe, environmentally acceptable, and resource-effective operation that proceeds quickly and in quantitative yield. Because most syntheses proceed from simple starting materials to complex targets, there are two general ways of approaching this ideal synthesis (i.e., achieving maximum relevant complexity increase while minimizing step count): the use of strategy-level reactions (e.g., the Diels –Alder reaction) that allow in one step for a great increase in target-relevant complexity or the use of multistep processes (e.g., polydirectional synthesis, tandem, serial, cascade, domino, and homo- and heterogenerative sequences) that produce similar or greater complexity changes in one operation. The design and development of new reactions and reaction sequences that allow for a great increase in target-relevant complexity are clearly essential for progress toward the next level of sophistication in organic synthesis.”46 While definitions of the “Ideal Synthesis” have been framed insightfully for various purposes over the years, like Hendrickson’s49 to fit computer analyses of synthetic routes, a 21st century definition of the goals of synthesis should be based, as we have emphasized for some time, on safety, step and time economy, and environmental considerations.3, 50 Increasingly, these principles are being emphasized in academia and industry.51

The 25th anniversary of the cedrene synthesis was impressively reviewed in 2006 by Chappell and Russell who beautifully surveyed other work in the field and concluded in their analysis: “we can see how the α-cedrene synthesis has set in train a series of studies that have demonstrated the immense power of this strategic level reaction”.52, 53 Further examples of the diverse studies of the arene-alkene cycloaddition in our laboratory are tabulated in Scheme 14 which underscores the reach of this strategy level reaction, delivering linear and angular triquinanes, propellanes, 5- and 7-membered rings, bridged bicyclics and other motifs with often unsurpassed step economy. A striking recent example of the continuing power of the arene-alkene photocycloaddition process to deliver step economical syntheses has been reported by Gaich and Mulzer in connection with the 5–8 step synthesis of penifulvin.54

Scheme 14.

Representative Syntheses based on the Arene-Alkene Meta-Photocycloaddition55

As the arene-alkene photocycloaddition, photothermal metathesis, macroexpansion and divinylcyclopropane projects moved forward, we also began to invest increasing effort in synthetic strategies based on metal catalyzed reactions. Our emphasis on cycloadditions followed logically from a global analysis of synthetic problems mentioned at the outset of this overview. Specifically, most targets contain rings of 3 to 16 members arrayed as monocycles, fused-, bridged- or spiro-cycles, underscoring the importance and general utility of methods for accessing these systems. Given that arene-alkene meta-photocycloadditions provide 5- and 7-membered rings through formal [3+2] and [5+2] cycloadditions, that the DVCP project provides 7-membered rings, and that the metathesis and macroexpansion projects provide access to 9–15 membered rings, our initial attention was directed at 8-membered ring synthesis. Further justification for this focus arose in part from the relatively limited cycloaddition methodology for accessing such rings and the increasing number of naturally occurring targets incorporating such rings, including taxol.

In the 1940s, in some of the earliest work in the field of metal catalyzed cycloadditions, Reppe and coworkers impressively showed that acetylene could be cyclotetramerized to form cyclooctatetraene in one step.56 It was also shown later that butadiene could be cyclodimerized to form cyclooctadiene. Both processes went on to become industrially important. At the time, these processes were not used in complex molecule synthesis as even modest substitution of butadiene would, if tolerated, provide complex mixtures of regio- and stereoisomers.57 In 1986, we reported the first nickel catalyzed intramolecular [4+4] cycloadditions as a strategy to overcome substitution problems and to control regio- and diastereoselectivity (Scheme 15).58 Remarkably, the intramolecular process proved to be tolerant of diene substitution and proceeded with complete regioselectivity, high diastereoselectivity (97%) and high yield (93%), in part fueling our view that these reactions could provide “fundamentally new approaches to several structural classes including taxanes, ophiobolins, and fusicoccins”. The relationship of the cycloadduct stereochemistry and functionality to taxol is noteworthy and synthetically attractive as dihydroxylations of the double bonds would provide the B-ring oxidation pattern of this, then unsolved, target.59 The intramolecular [4+4] cycloaddition process served well in other syntheses as illustrated by step economical syntheses of asteriscanolide (64, 13 steps, Scheme 16)60 and of salsolene oxide (67, 8 steps, Scheme 17)61.

Scheme 15.

The First Intramolecular Metal Catalyzed [4+4] Cycloaddition

Scheme 16.

Intramolecular Metal Catalyzed [4+4] Cycloadditions: Synthesis of Asteriscanolide

Scheme 17.

Intramolecular Metal Catalyzed [4+4] Cycloadditions: Synthesis of Salsolene Oxide

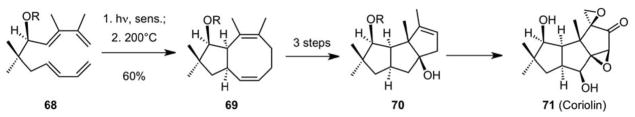

A point that cannot be over-emphasized in looking to create new solutions to problems is the value of diverse experiences. With all of our photo[2+2]cycloaddition work in mind, with prior success in strain driven DVCP Cope rearrangements, and with bis-dienes in hand, we were in a position to “connect the dots” and explore whether intramolecular photocycloadditions of bis-dienes could provide a practical route to divinylcyclobutanes (DVCB) which through a strain driven Cope rearrangement would provide a non-metal approach to 8-membered rings (Scheme 18). This study went well, providing the first examples of the intramolecular [2+2] photocycloaddition of bis-dienes and a powerful route to DVCB, from which 8-membered rings as well as their triquinane derivatives are derived through a transannular closure. This latter process was a theme in our earlier medium ring work.62 This strategy led to a formal63 synthesis of coriolin (71, Scheme 18) in our lab and more recently figured in a related transannular closure to other triquinanes based on a different way to make 8-membered rings64.

Scheme 18.

A Photo[2+2]/Cope Sequence for 8-membered Rings: Formal Synthesis of Coriolin

While serendipity is often given more credit than opportunistic observation and hypothesis driven research, all play a role in the advancement of science. In the course of our studies on the intramolecular [4+4] cycloaddition of bis-dienes, we observed, for example, a competing process, the nickel catalyzed [4+2] cycloaddition of a diene across an alkene (74, Scheme 19).58 This was not unexpected as Reppe and others had observed this competing pathway with simple butadienes. However, its utility in complex molecule synthesis was little advanced but potentially of great value, especially if it could be controlled in an intramolecular process similar to that which we observed with the [4+4] cycloaddition. While this metal catalyzed [4+2] reaction is a process that provides a Diels-Alder-like product, for many diene-dienophile combinations, the Diels-Alder cycloaddition would not be viable because of a poor HOMO-LUMO gap. Drawing on our prior investigation of intramolecular reactions of bis-dienes, in 1989 we reported the first nickel catalyzed intramolecular [4+2] cycloadditions of diene-ynes.65 Illustrative of the utility of this process, diene-yne 76 is converted in 98% yield to cycloadduct 78 at 25°C (16h) while the thermal conversion of 76 requires heating for days at 160°C (Scheme 19).

Scheme 19.

Metal Catalyzed [4+2] Cycloadditions of Dienes and Alkynes

We66 and others67 extended this method to alkenes and allenes and to other metal catalysts. The allenes proved especially interesting as they work well with 5-, 6-, and 7-atom tethers giving rise to 5-6, 6-6, and 6-7 bicycles, common to a variety of important targets. Moreover, depending on the nature of the catalyst one can effect cycloaddition across the terminal or internal allene double bond, the former giving a 6-6 bicycle 83 and the latter a 6-5 bicycle 85 with a quaternary center (Scheme 20).

Scheme 20.

Metal Catalyzed [4+2] Cycloadditions of Dienes and Allenes.

There are many uses for such metal catalyzed [4+2] cycloadditions in synthesis as they circumvent the frontier molecular orbital constraints of conventional concerted reactions. For example, in an approach to steroid synthesis, diene-yne 86 does not undergo a Diels-Alder reaction upon heating. Rather, it is unreactive up to 175°C, at which point it undergoes decomposition. In contrast, 86 in the presence of a nickel catalyst undergoes a smooth multistep [4+2] cycloaddition, giving the cyclohexadiene product 87 with an angular methyl group and complete diastereoselectivity in 90% yield at 80°C (Scheme 21).

Scheme 21.

Metal Catalyzed [4+2] Cycloadditions of Dienes and Alkynes: Steroid Synthesis

Inspired by the highly effective Diels-Alder strategy to indole alkaloids reported by the Martin Group,68 we examined the corresponding metal catalyzed approach, which allowed for a room temperature metal-mediated cycloaddition (89 to 90) that proceeded in 88% yield (Scheme 22).69 The cyclohexadiene product was subsequently converted to 19,20-didehydroyohimbane 91. The corresponding thermal reaction of our diene-yne precursor (89) proceeded only at 150°C with cleavage of the Boc group and gave only a 45% yield of the desired product.

Scheme 22.

Metal Catalyzed [4+2] Cycloadditions: Yohimban Alkaloid Synthesis

A theme was emerging in these metal catalyzed cycloadditions that echoed lessons learned from Gilbert Stork. He of course was part of the Stork-Eschenmoser hypothesis on biosynthetic cation-alkene cyclizations70 which has been interpreted in many ways but in my view called attention to how Nature recycles or sustains reactivity, by generating a carbocation to initiate a cyclization, which in turn generates a second carbocation and so on. Thus a simple one-bond forming reaction proceeding with only a modest complexity gain becomes a controlled oligomerization, regenerating reactivity at each bond-forming event until a termination step occurs, affording a highly complex product. When examined through this lens, the metal-catalyzed [4+4] cycloadditions involve initial metal activation to produce a first CC bond forming event, generating a metal complexed intermediate that undergoes reductive elimination (RE) to afford 4-, 6-, or 8-membered rings (Scheme 23). Reactivity is thus terminated. It was clear that the reactivity of the metal-complexed intermediate, shown here as a bis-η-1 metallacyclopentane, could be propagated by capture with various 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-carbon additives to access other rings through novel multicomponent processes. Indeed, butadiene itself gives rise to 6-, 8- and 12-membered rings depending on the catalyst and conditions. All but one of the following multicomponent processes has since been observed.

Scheme 23.

Metal Catalyzed Multicomponent [m+n+o] Cycloadditions and Cascades

In the case of our metal catalyzed [4+2] cycloadditions, this concept of “sustaining reactivity” suggested that the metallacycles formed in the initial steps of the reaction might be trapped with 1-, 2-, 3- or 4-carbon co-reactants to access rings of 5- to 10-members. For example, with CO, 5- and 7-membered rings would be formed through three-component processes (Scheme 24). When this idea of extending the [4+2] process to a three-component process was tested, all three modes ([4+2], [2+2+1], and [4+2+1]) of reaction were observed (Scheme 25).71, 72 The [2+2+1] process was selected for optimization, providing the first examples of intra- and intermolecular dienyl Pauson-Khand reactions (Scheme 26).71, 73 This concept of “sustaining reactivity” or “regenerating reactivity” laid out by us in the form of “connectivity analysis” in 1993, is a core principle in multicomponent reaction design.3a,74 Collectively, such reactivity sustaining cascades are amongst the most powerful ways of building complexity, and thus value, with step economy.

Scheme 24.

Metal Catalyzed Multicomponent [2+2+1], [4+2+1] and [4+2+2] Cycloadditions

Scheme 25.

Diverting a [4+2] Cycloaddition into Multicomponent [2+2+1] and [4+2+1] Cycloadditions

Scheme 26.

The Dienyl Pauson-Khand [2+2+1] Cycloaddition

A further illustration of this concept of sustaining reactivity involving [4+2] intermediates was reported by the Gilbertson group in the form of a [4+2+2] three-component process for 8-membered ring synthesis in which the previously noted metallacycles were captured by an alkyne.75 The Evans group reported a variant involving enynes and dienes as precursors for a [4+2+2] process.76 Unrelated to our diene-yne work, the Murakami group reported another noteworthy example of a [4+2+2] process in which a cyclobutanone is used as a 4-carbon component.77 Our own studies used a diene-ene to form the initial metallacycle and an alkyne trap to form an 8-membered ring product (109, Scheme 27).78 A recent example pertinent to the above diene-ene capture with CO is provided by using a methylenecyclopropane to achieve a [4+2+3] MCR.79

Scheme 27.

An Alkyne Diverted [4+2] Reaction: A 3-Component [4+2+2] Cycloaddition

An especially important aspect of our studies up to that point centered on the special reactivity of dienes, which we dubbed the “diene effect”.80 The general importance of this effect is that dienes serve as 2-electron partners in many reactions for which conventional 2-electron pi-systems (alkenes, alkynes and allenes) fail to react. We interpret this as an energy lowering coordination effect between the metal catalyst and the second double bond of the diene. For example, the Pauson-Khand reaction is based on an alkyne serving as a 2C/2e component with an alkene partner. Bis-alkenes do not undergo this three-component [2+2+1] reaction. In striking contrast, we found that a diene can be used instead of an alkyne to effect, with alkenes and CO, the first three-component [2+2+1] reaction leading to cyclopentanones (112, Scheme 28).81 We subsequently showed that allenes and dienes in the presence of CO also afford a [2+2+1] product in high yield.82,83

Scheme 28.

The Diene Effect: Diene-activated [2+2+1] Cycloadditions with Alkenes

In addition to the unique reactivity of dienes in the above processes, we found that dienes more generally also participate in a variety of interesting [2+2], [2+2+2] and [2+2+2+2] reactions with various pi-systems.84 The crossed cyclo-pseudo-trimerization of 3 alkenes is of special significance as it proceeds in 99% yield and produces as illustrated 6 stereocenters (115, Scheme 29). While this rare process benefits from enhanced reactivity due to proximity and strain, it provides encouragement that one might eventually be able to make such processes more general with conventional alkenes.

Scheme 29.

The Diene Effect: Rare [2+2] and [2+2+2] Cycloadditions of Alkenes

Representing a confluence of our earlier studies on vinylcyclopropanes and metal catalyzed [4+2] cycloadditions, we reported in 1995 the first metal catalyzed [5+2] cycloadditions of vinylcyclopropanes and pi-systems, a homolog of the Diels-Alder cycloaddition.85 Drawing inspiration from the Diels-Alder [4+2] cycloaddition, our idea was to replace the 4-carbon diene with a 5-carbon vinylcyclopropane (VCP) to access 7-membered rings through a formal [5+2] cycloaddition (Scheme 30). However, VCPs are in general insufficiently activated for such a thermal process. As noted by others, simple vinylcyclopropanesdo not react “even [with] the strongest dienophiles”.86

Scheme 30.

The Diels-Alder [4+2] Cycloaddition as Inspiration for a New [5+2] Cycloaddition

Our approach to address the lack of reactivity of VCPs was to use pi-directed metal-mediated CC bond activation. It was known that VCPs could be converted to cyclopentenes in the presence of metal catalysts.87 We reasoned that the latter metal catalyzed “carbon-carbon bond activation” process might lead to a metallacyclic intermediate sufficiently long lived to be captured by a second pi-system to provide, after insertion and reductive elimination, a 7-membered ring product (Scheme 31).

Scheme 31.

Pi-directed Metal Catalyzed CC Bond Activation: Genesis of the [5+2] Cycloaddition

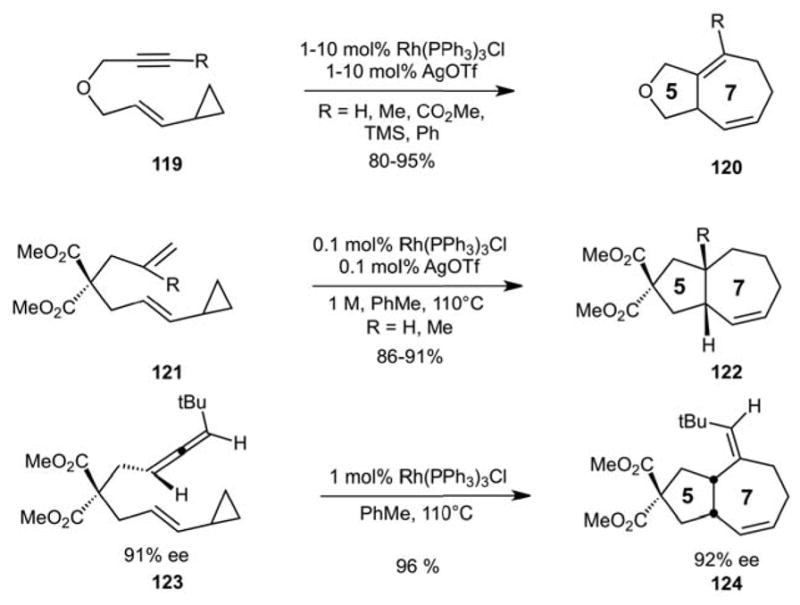

This idea of CC activation and trapping proved to be a remarkable success and opened a field of methodological studies based on vinylcyclopropanes explored and expanded by us (Scheme 32) and subsequently and impressively by many others.88 The process proved to be remarkably robust, working with alkynes, alkenes and allenes. We and others subsequently showed that it can be effected with other catalysts. As noted in our inaugural manuscript “This method establishes the experimental framework for conceptually new approaches to seven-membered-ring compounds and suggests a greater role for vinylcyclopropanes as diene homologues in a wide range of transition metal catalyzed reactions and more generally for the catalyzed addition of strained rings across pi-systems.”

Scheme 32.

The First Metal Catalyzed [5+2] Cycloadditions

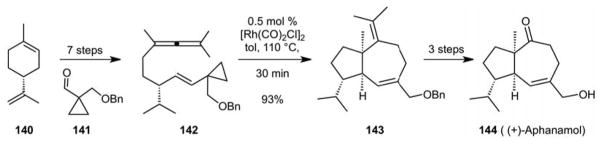

In 1998, we reported a further major advance in this area: the first metal catalyzed intermolecular [5+2] cycloadditions of VCPs and pi-systems (Scheme 33).89 This breakthrough was not readily achieved as mono-substituted VCPs react only slowly and this was missed in our early work. Introduction of a second group, such as OTMS, geminal to the vinyl group was the key as it served to populate a reactive conformation for the activation process.90 This study significantly extended the reach of this new reaction as it now allowed one to use alkynes, some of the most abundant commercial feedstocks, to produce added value and previously difficult to access 7-membered ring building blocks. We subsequently reported the extension of this reaction to allenes.91 The first applications of this reaction in synthesis followed with a synthesis of (+)- dictamnol (139, Scheme 34)92 and (+)-aphanamol I (144, Scheme 35).93, 94

Scheme 33.

The First Intermolecular Metal Catalyzed [5+2] Cycloadditions

Scheme 34.

The First Metal Catalyzed [5+2] Cycloadditions: Synthesis of Dictamnol

Scheme 35.

The First Metal Catalyzed [5+2] Cycloadditions: Synthesis of Aphanamol

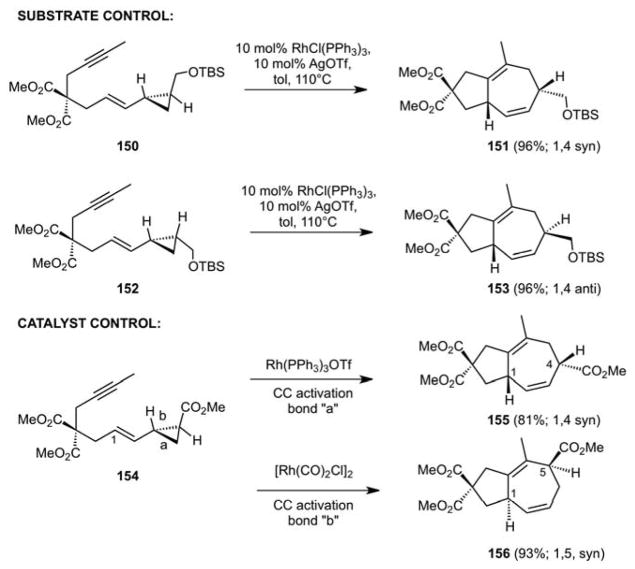

Our subsequent studies on the [5+2] cycloaddition of VCPs and pi-systems examined the effect of substitution of the C1-95 and C2-positions96,97 of the VCP (Scheme 36). In the absence of selectivity, one would expect a mixture of constitutional isomers as indicated. Significantly, we found that cleavage of the less substituted bond (bond “a”) is preferred, and not unlike double bond geometry being preserved in the Diels-Alder cycloaddition, we found that cyclopropane stereochemistry is conserved in the [5+2] cycloaddition. Thus, a trans-disubstituted VCP 150 gives diastereomer 151 while the cis-disubstituted VCP 152 gives the complementary diastereomer 153 (Scheme 37). Significantly, the catalyst can also be used to control selectivity as indicated by the conversion of 154 to 155 or 156 depending on the choice of catalyst.

Scheme 36.

Diastereo- and Regio-control in CC Activation and Cycloaddition of VCPs

Scheme 37.

Substrate and Catalyst Control of Diastereo- and Regioselectivity

In addition to diastereoselectivity studies, we also reported the first asymmetric version of the [5+2] cycloaddition using a chiral cationic Rh BINAP catalyst (Scheme 38).98 The Hiyashi Group has more recently also reported a highly effective chiral phosphoramidite catalyst for this process.99 We and others have also reported other catalysts that effect [5+2] cycloadditions between VCPs and pi-systems, including cationic rhodium,100 rhodium NHC,101 nickel,102 ruthenium,103 and iron104 systems. Using a water-solubilizing tetrasulfonic acid ligand 163 we were able to show that the [5+2] cycloaddition can be conducted in water.105 In addition to the “green” value of water as a solvent, an attractive aspect of this approach is that the water-soluble catalyst can be reused and the new substrate can be added without solvent. When the reaction is complete, one simply removes the organic product layer and recharges the remaining catalyst water layer with new starting material. While some have expressed reservations about water as a reaction solvent, many fields of opportunity, especially in the life sciences, will be opened through the use of catalysts that function in cells and organisms. Nature’s limited use of the periodic table could be vastly supplemented through the introduction of water functioning bioorthogonal catalysts.

Scheme 38.

New Catalysts: Chiral, Water-Soluble, Cationic, and Carbene Catalysts

In the late 1980s, we initiated a now decades-long collaboration with Ken Houk and his coworkers, initially directed at our studies on arene-alkene meta-photocycloadditions and then nickel and eventually other metal catalyzed cycloadditions.106 These mechanistic and theoretical studies have expanded to other new reactions and continue to the present with studies on our [5+2] cycloaddition and various other metal catalyzed processes. These collaborative efforts have been exceptionally important, generating much-valued hypotheses for the mechanisms of the reactions, substitution effects, and their chemoselectivity, regioselectivity, and diastereoselectivity. Of great significance are the coworkers who have come out of this collaboration, including Peng Liu, Paul Ha-Yeon Cheong (Oregon State University), and Zhi-Xiang Yu (Peking University), the last now a major figure in advancing the [5+2] cycloaddition and related reactions.107 The reader is encouraged to explore several significant reviews on seven-membered ring synthesis that capture many of the creative contributions to this field from many laboratories.108

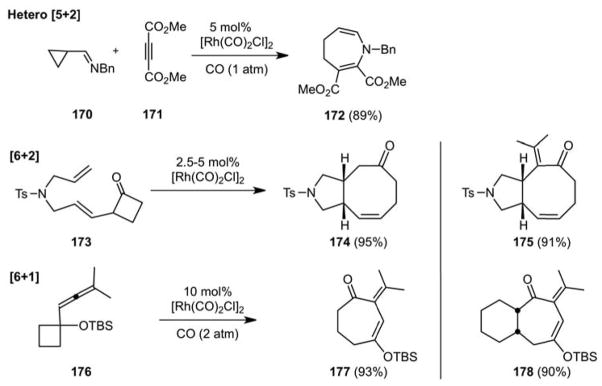

New reactions beget new reactions as they change the way we think about bond construction. The first idea that derived from studies on the metal catalyzed reactions of vinylcyclopropanes is that vinylcyclobutanes might behave similarly. This proved on first pass not to be possible, presumably owing to the decreased “per bond” strain of the latter ring. To circumvent this diminished reactivity, we reasoned that a vinylcyclobutanone (VCB) would work well as it would be more strained and its carbonyl oxygen would also direct the metal catalyst for CC activation of the proximate bond. This proved to be a successful approach and gave rise to the first [6+2] cycloaddition of VCBs and pi-systems for 8-membered ring synthesis (Scheme 39).109 Allene directed CC bond cleavage provided another strategy to activate simple cyclobutanes, now in a [6+1] process (Scheme 39). The concept of “atom analogy” suggests that these reactions could be extended to heteroatom counterparts and indeed this was observed in the first hetero [5+2] cycloaddition of an iminocyclopropane and a pi system (Scheme 39).110

Scheme 39.

New Reactions beget New Reactions: Hetero [5+2] Cycloadditions and [6+2] and [6+1] Cycloadditions

In the course of the above studies, we observed that the [6+2] cycloaddition would proceed in some cases with the loss of CO and the formation of a [5+2] product, i.e., a 7-membered ring. While the result was serendipitous, the response was hypothesis driven. If a [6+2] cycloaddition of a VCB could through the loss of CO produce a [5+2] product (i.e., a [6+2−1] product), then a [5+2] cycloaddition of a VCP could in the presence of CO produce a [5+2+1] product. The math made sense and the chemistry did as well. In 2002, we reported the first [5+2+1] cycloadditions of VCPs, pi-systems and CO, a 3-component process for 8-membered ring synthesis (Scheme 40).111 This was extended to allenes112 and in collaborative studies with the Yu group applied to intramolecular [5+2+1] cycloadditions.113 The Yu group has impressively deployed the intramolecular [5+2+1] cycloaddition in total synthesis.114 We subsequently also found that certain aryl alkynes react with VCPs in the presence of CO to produce a [5+2+1+1] cycloadduct, a relatively rare four-component process and one of the most mechanistically and strategically unexpected ways to make indanones from a 9-membered ring intermediate.115

Scheme 40.

A New 3-Component [5+2+1] Reaction for 8-membered Ring and Diquinane Synthesis

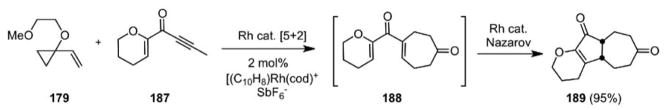

As noted previously, new reactions beget new reactions which in turn allow for the invention of new reaction cascades or serialized processes. While reactions typically proceed with the formation of one or two new bonds, serialized or multicomponent reactions “sustain reactivity”, allowing for more bond forming events and thus a greater increase in molecular complexity before reaction “termination”. Early in our work, and in this overview, we described such a serialized pairwise metathesis-transannular ene combination that produces in one operation (light and heat) a bicyclic product via a medium ring intermediate. With our growing knowledge of the [5+2] cycloaddition, a formal homologous Diels-Alder reaction, we were attracted by the notion that teaming it with the complexity increasing value of the conventional Diels-Alder cycloaddition, i.e., deploying back-to-back cycloadditions, would allow step economical access to a variety of 5-7 polycycles. This idea proved to be highly effective in practice. The alkyne specificity of the [5+2] cycloaddition resulted in the formation and capture of a Diels-Alder diene, producing in one operation and on scale (100 mmol) from commercially available starting materials, polycycles of interest as kinase inhibitors (186, Scheme 41).116 An often under-appreciated aspect of such serialized reactions is that the one operation process can be more effective than the stepwise process, as the first formed product (the diene in this case) is removed as it forms in a second reaction, thereby avoiding its involvement in side reactions.

Scheme 41.

[5+2]/[4+2] Cascades: A One-Step, Scalable Route to Kinase Inhibitors

More recently, we teamed the [5+2] cycloaddition with a Nazarov cyclization to produce in one operation 5-7 ring systems (Scheme 42).117 Significantly, the cationic rhodium complex [(C10H8)Rh(cod)+SbF6−] was able to catalyze both reaction steps, cleanly providing 189 in a remarkable 95% isolated yield in this catalyst cascade.

Scheme 42.

Cascade Catalysis: The Metal Catalyzed [5+2]/Metal Catalyzed Nazarov Cascade

Our work with new, serialized, and multicomponent reactions continues to be driven, as articulated in our 1985 silphinene manuscript, by the goal of achieving complexity and thus value in a step economical if not ideal way.4 While not all covered in this overview, we have thus far designed and developed a number of novel or new metal catalyzed processes including two component [4+4], [2+2], [4+2], [3+2], [5+2], [6+1] and [6+2] cycloadditions, three component [2+2+1], [2+2+2], [5+2+1], [4+2+1], and [4+2+2] cycloadditions, and four component [2+2+2+2] and [5+2+1+1] cycloadditions.118, 119 There are more under evaluation now and more that are theoretically possible.120 Indeed, in the 1990s we started to explore the latter issue using simple graph theory.121 As background for our thinking, it is important to recall that when one is confronted with the challenge of producing a synthetic target, one is encouraged to reason in reverse, in essence to perform a retrosynthetic analysis. In that process, one disconnects bonds that in a forward synthesis direction would be made through known reactions. A complementary approach that attracted our attention was to not restrict retrosynthetic analyses to known reactions, i.e., what is known, but rather open such analyses to what is possible. The problem of generating a synthetic strategy thus changes from using what is known to imagining what might be possible. Of course, because all of reaction space is not now known from a chemical perspective, this approach was designed to focus only on possible graphical connections and add the chemistry afterwards as needed. This generally is not an impediment as most bond forming connections are made through concerted or stepwise reactions and the latter generally through one or more of seven reactive intermediates (anions, cations, radicals, carbenes, radical anions, radical cations, and organometallic systems). Synthetic chemists are well versed in choreographing such connections. This search for pure graphical connectivity advantages also avoids chemical bias at the initial level of analysis because the retrosynthetic analysis is driven only by the magnitude of decrease in graphical complexity and as emphasized previously that correlates with step economy.

Using this approach, termed “connectivity analysis”, one can quickly analyze all possible graphical solutions to a given problem. For example, there are only 3 ways to make a 3-membered ring: acyclic closure (including rearrangements), [2+1], and [1+1+1] strategies. For a 4-membered ring there are 5 graph theoretical solutions of which 4 are known: acyclic closure, two 2-component processes ([2+2] and [3+1]), one 3-component process ([2+1+1]) and an as yet unexplored 4-component process ([1+1+1+1]). An attractive part of this approach is that one can define what is possible and its creative component is to then imagine what chemistries would enable it. It can also be applied to the task of generating all graphical solutions to synthetic targets. For example, we have used this heavily in considering all possible approaches to the synthesis of taxol and other targets.122 By selecting for the retrosynthetic path of greatest complexity decrease and thus in a synthetic direction greatest complexity increase, one can easily identify all strategies and rank them by complexity change and thus step economy.123 A computer program based on our connectivity analysis, dubbed CONAN (Scheme 43), was produced by our collaborators in Marseille, R. Barone and M. Chanon.124 Some CONAN predicted121 disconnections are given in Scheme 43.

Scheme 43.

Connectivity Analysis (COANAN): A Chemically Unbiased Graph Theoretical Approach to Identifying Preferred Complexity Increasing, Step Economical Strategies

CONAN coevolved with our interest in another structural class – 8-membered ring containing targets, of which the most important target at the time was taxol. We have published a CONAN analysis of all possible graph theoretical approaches to taxol.122 Taxol had a rocky development path encountering some science challenges but mostly “naysayer” problems that almost blocked its clinical testing. Fortunately, it was championed by some scientists with vision, and it proved its value and the value of their commitment in human trials initially against breast and ovarian cancers. As its clinical success grew, so too did issues associated with its then limited availability. Over 50 groups at one point were involved in studies directed at the synthesis of taxol, producing a range of rich contributions to the field. Eventually, only 7 groups produced a total or formal synthesis.125 A global search for natural sources of taxol proceeded concurrently. Even landscaping nurseries that sold yew trees were considered. Eventually, taxol was supplied through semi-synthesis from a natural precursor found in a renewable source.126 Our own approach to this problem “was guided by the goal of producing a practical synthesis of taxol that could also be used to make analogues as needed to elucidate the novel mode of action of taxol at the molecular level and to develop second generation drugs.” Then and now, it was our view that designed analogs could be realized which would be clinically superior and synthetically more accessible. Simply put, natural products are great leads but they are not evolved for human use.

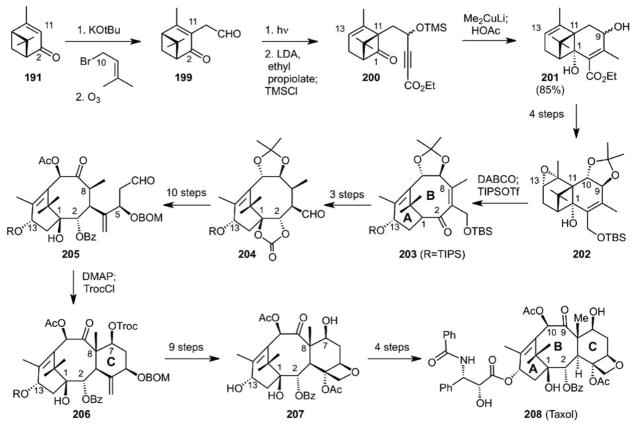

Our initial approach to the synthesis of taxol was based on the above-noted nickel catalyzed [4+4] cycloaddition. While advancing this forward, we also initiated an approach that eventually led to the shortest synthesis of taxol thus far and from our perspective an even more important goal: a 5-step route to the homo-chiral, carbotricyclic taxane core from which better analogs could be created. This synthesis started with homo-chiral pinene (190), a major component of turpentine abundantly available from pine trees.127 Multi-mole allylic CH activation with a cobalt catalyst using air as the oxidant produced verbenone (191) which upon alkylation and photochemical rearrangement was converted to the alkylated chrysanthenone 194. Lithium halogen exchange resulted in closure of the pro-B-ring to give 192. Epoxidation of the C12–C13 alkene from the sterically less congested face and strain-driven fragmentation gave the homo-chiral carbotrycyclic core of the taxanes (197) in 5 steps from pinene. Oxidation of the bridgehead enolate and reduction gave the core tricycle with differentiated functionality ready for further synthetic elaboration (195, Scheme 44). This synthesis was scalable with starting runs of 1–2 moles. While modified somewhat to access taxol (208, Scheme 45), this strategy delivered a uniquely short solution to the taxol synthesis problem based again on pinene and featuring an aldol closure (205 to 206) to complete the C-ring. The reader is referred to the primary literature on this synthesis as it more fully covers some remarkable bond forming choreography. Significantly, this strategy enabled access to analogs. We will return to this point at the end of this overview as our ability to make and modify taxol figured significantly in a novel strategy that we introduced later to overcome taxol resistant cancer.

Scheme 44.

The Pinene Path to Taxol Analogs: 5-Steps to the Homo-Chiral Taxane Tricyclic Core

Scheme 45.

The Pinene Path: Total Synthesis of Taxol

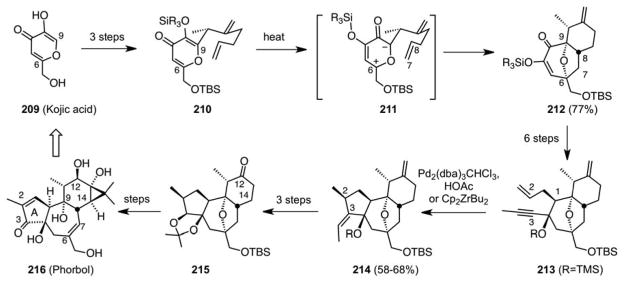

As noted at the outset of this overview, our synthetic interests over the years have been heavily coupled to therapeutic opportunities, such as taxol, and more generally studies directed at the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of disease. Our initial interest in seven-membered ring synthesis, for example, was fueled at the time by the anticancer activity of certain pseudoguaianes and more significantly by the fascinating tumor promoting activity of tiglianes such as phorbol esters. At the outset of our work, members of both families of targets had not been synthesized and relatively little was known about the basis for their activities. The phorbol esters were especially intriguing as they are among the most potent tumor promoters, agents that are not carcinogenic but amplify the effects of carcinogens. Our interest was driven by a fundamental perspective, the best way to address disease is to prevent it and that in turn requires a molecular understanding of how it starts. It had long been known that tumor promoters figure in carcinogenesis but the mechanism(s) of amplification was not known. Our thinking at the time focused initially on the development of the expertise needed to make phorbol esters and then to use that to make related probes of mechanism and targets. Our initial approach to the synthesis of phorbol esters was based on the divinylcyclopropane rearrangement and was designed explicitly to address comprehensively tigliane, daphnane and ingenane targets.128 We also explored a Diels-Alder strategy,129 and eventually succeeded in accessing tiglianes using a different but equally useful strategy involving a [5+2] cycloaddition of a pyrylium zwitterion and an alkene (Scheme 46).130 A second generation synthesis quickly followed131 and an asymmetric version was reported several years later.132, 133

Scheme 46.

Oxido-Pyrylium [5+2] Cycloadditions: The Total Synthesis of Phorbol

Uncovered in the 1950s and advanced contemporaneously by Hendrickson,134 Sammes,135 and our group amongst others, the oxidopyrylium [5+2] cycloaddition proved to be a robust process for seven-membered ring synthesis.136 It served not only as a key strategy level reaction137 for our phorbol ester synthesis (213, Scheme 46) but also figured in the synthesis of the even more complex daphnane target, resiniferatoxin (220, Scheme 47).138, 139 It has also provided a gateway synthetic route to daphnane diterpene orthoesters, leading to des-epoxy-yuanhuapin and related analogs (224, Scheme 48).140

Scheme 47.

Oxido-Pyrylium [5+2] Cycloadditions: The Total Synthesis of Resiniferatoxin

Scheme 48.

Oxido-Pyrylium [5+2] Cycloadditions: Synthesis of Des-epoxy-Yuanhuapin, a Gateway Strategy for accessing Diterpene Orthoesters

While unrelated to the above methodological studies, our successful efforts with the synthesis of phorbol provided the expertise needed more recently to address another tigliane problem of synthetic and therapeutic significance. Prostratin (227, Scheme 49) is currently a pre-clinical lead being advanced for the eradication of HIV/AIDS. Current anti-retroviral therapy (ART) stops disease progression by reducing or eliminating active virus. However, it does not eradicate disease. Genomically encoded provirus harbored in reservoir cells in infected individuals resupplies active virus over time. To eradicate the disease, this latent viral source must be eliminated. Prostratin activates latent cells, potentially allowing for their clearance by viral cytopathic effects, immune effector mechanisms, or other processes. If used in combination with ART, eradication of both the active and latent sources could be realized. Until recently, prostratin was available only in limited and variable amounts from plant sources.141 In 2008, we reported a five-step semi-synthesis of prostratin from phorbol, exploiting our prior synthetic studies with the latter system (Scheme 49).142 Our approach recognized that deoxygenation next to a cyclopropane would proceed with strain-driven cleavage of the latter. This was indeed observed. While seemingly undesired, the process did serve to remove the C12 oxygen of phorbol and thus what remained was to rebuild the cyclopropane ring. Using a variant of chemistry explored by Kishner and Freeman,143 we were able to rejoin carbons 13 and 15 to produce prostratin (227) and, more importantly, designed analogs. The power of synthesis and design is apparent here as this synthesis not only provides a reliable and scalable laboratory source of the natural product and clinical lead but also a source of more active analogs. Our designed analogs are up to 100-fold more potent that prostratin in binding to PKC, the target implicated in the HIV activation pathway. Significantly, these are also effective in inducing activation of reservoirs cells ex vivo in blood samples taken from patients on suppressive therapy.

Scheme 49.

Leads for HIV/AIDS Eradication: Semi-synthesis of Prostatin and its Analogs

At the outset of our phorbol ester research, no prior work had been reported on its synthesis. We were understandably discouraged by some from taking on this formidable task because in addition to the lack of prior art, the tigliane targets themselves were complex for the time and known to be sensitive to acid, base, heat and light. They also decompose in the air and are biohazards at nanomolar concentrations. The ultimate solution to these formidable problems was found in the courage, creativity and determination of co-workers. That noted, it did take years to achieve the synthesis of phorbol, leaving one wondering, as I did earlier during my Yale interviews, about better and quicker ways to reach such goals. For many problems, the “better and quicker” way unfolded in the form of what we call “function oriented synthesis”. In many cases and increasingly so now, interest in synthetic targets is in part driven by their synthetic challenge but also in large measure by their biological activity or use as materials, imaging agents, research tools or therapeutic leads, in other words, by their function. Our target oriented synthesis approach sought a step economical route to the target structure but the complexity of the problem and the state of methodology precluded realization of a timely, step-economical solution. Over the years, this same situation has been experienced by many and has, in turn, more recently, dampened the enthusiasm by some for natural products. “They are too complex”, “they don’t fit the ‘rules’ ”, and “they are too difficult to make or isolate” are familiar refrains. At the same time, it does not make sense to turn away from the treasure trove of latent knowledge provided by 3.8 billion years of chemical evolution, the largest, self-renewing library known.144

Obviously, one solution that continues to merit attention is to grow the base of synthetic methodology so that it would be able to deliver even more complex targets in a practical and timely fashion, i.e., with step and time economy. That takes development time and, for many current problems, time is in short supply. For some systems, another approach is to recognize that a major factor driving interest in natural products is not only the synthetic challenge associated with their structure but also that associated with their function, including biological activity. Thus, if instead of focusing only on target structure one would focus also on target function, one could, with careful and creative analysis of a natural product lead, identify key features that might be necessary for activity and design new, more accessible and even more active targets. Translating nature’s library in this way provides a blueprint for the design of targets that would exhibit superior function and be accessed in a more step and time economical fashion.145 As this author has noted in other venues, when we humans learned that the concavity of a bird’s wings was a key to flight, we did not seek to synthesize birds but instead used that fundamental knowledge to create planes and jets whose functions vastly exceeds natural systems. This “function oriented synthesis” (FOS)146 approach thus addresses many of the problematic issues associated with natural products as synthesis- and function-informed design allows one to create molecules with potentially superior activity that can be produced in a practical fashion. Creative design can win the day, producing more readily accessed targets with superior activity.

Scheme 50 graphically illustrates the value of a shift in emphasis from structure to function and how a hypothesis on the pharmacophore requirements coupled with synthesis informed design can be used to access simpler targets with comparable or better function in a timely step economical fashion. Our first experimental exploration of this approach was reported in the 1980s in connection with phorbol esters (228).18 While the phorbol ester synthesis, then in progress, required several years to complete, it is noteworthy that the synthesis of the designed functional arene analog 229 (R = lipids) required only 2 weeks. Both compounds activate protein kinase C (PKC). This study thus produced the first designed PKC modulators.147 The power and unique benefit of this FOS approach to leads lies principally between random screening and lead optimization. In the former, one screens for activity, while in the latter one seeks to optimize activity. FOS tests hypotheses and seeks to design for activity inspired by, but not constrained to, the structure of the natural lead.

Scheme 50.

Function Oriented Synthesis: Step Economy and Superior Function by Design

The emergence in the late 1980s of “ene-diyne” DNA cleaving agents with unprecedented and complex structures and promising in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity provided an early test of the FOS strategy. Dynemicin (231, Scheme 51) was one of the early natural product leads in this series.148 While stable with an epoxide in place that maintains a transoid butane-like subunit in the 10-membered ring, dynemicin undergoes epoxide cleavage removing this constraint and triggering a Bergman cyclization149 to an arene diyl capable of abstracting hydrogens from the deoxyribosyl backbone of DNA, leading to DNA cleavage. Impressive syntheses of dynemicin were subsequently reported.150 We took an FOS approach designing a highly simplified functional core structure (232) based on mechanistic analysis and computer models which predicted the then unknown absolute stereochemistry of dynemicin.151, 152 Our idea was that the group on nitrogen would be the trigger, retaining electron density until released. Cleavage of that group under a variety of conditions (e.g., acidic, photochemical, biological) would increase electron density on nitrogen and thus trigger epoxide opening and Bergman cyclization (Scheme 51).153 Initial acid catalyzed epoxide opening was indeed shown to work, giving smoothly 234. The performance of a photoactivable derivative (235, Scheme 52) was tested next in the presence of circular, supercoiled DNA.154, 155 When incubated with pBR322 DNA and irradiated, this designed agent caused both single and double strand cleavage of DNA. No DNA cleavage occurred in the absence of light and more cleavage occurred when irradiation was extended. Thus, through FOS, a designed functionally competent DNA cleaving agent was achieved in a synthesis requiring only 8 steps. It is noteworthy that FOS does not preclude one of the important other justifications for natural product synthesis, namely the inspiration of new methodology. Natural product inspired design can be used similarly and in this case led to an effective desilylative closure of a silyl terminated alkyne to produce the strained 10-member ring.

Scheme 51.

Function Oriented Synthesis: Designed Dynemicin Analogs

Scheme 52.

FOS Designed Photonucleases cleave DNA: Light Activatable DNA Cleavage

An even simpler approach to DNA cleaving agents was inspired by our studies on a route to indoles as applied to the synthesis of 7-methoxymitosene (241, Scheme 53) in which a triazole is used to photochemically generate a diyl which is trapped to form an indole.156 Reasoning by analogy we proposed that abundantly available benzotriazoles upon proper derivatization would upon photolysis generate a DNA cleaving diradical (244, Scheme 53). This led to the successful demonstration that such simple and simply-derived triazole systems can serve as “photonucleases”.157, 158, 159 Both single and double strand DNA cleavage was observed. Significantly, by attaching a DNA recognition element to the DNA cleaving triazole element (246), one can achieve selective DNA cleavage, in this case predominantly at one site in a 167 base pair sequence (Scheme 54).

Scheme 53.

FOS Designed Triazole Photonucleases cleave DNA: Light Activatable DNA Cleavage

Scheme 54.

FOS Designed Photonucleases with DNA Recognition Elements Selectively Cleave DNA

Concurrent with our phorbol ester and ene-diyne synthesis and function oriented synthesis (FOS) studies, we became interested in the synthesis, structure and activity of bryostatin (247, Scheme 55). Isolated by Pettit first in 1968, bryostatin at the time was a new and unique marine derived natural product incorporating three hydropyranyl rings into a macrocyclic lactone.160 It exhibited a range of novel activities and while beyond the scope of this overview, it has since been entered into numerous clinical trials for the treatment of cancer and shows promise for the treatment of cognitive dysfunction. Indeed the author is affiliated with a new company directed at using this and related agents to treat Alzheimer’s disease. Remarkably, bryostatin, by analogy to prostratin noted previously, is also a lead in an as yet unrealized but hugely important goal of eradicating HIV/AIDS by depleting latent viral reservoirs, the source of continuing infection. These activities are thought to be associated with modulation of PKC isoforms, although other protein targets have been suggested. Our interest in this class of compounds followed naturally from our initial interest in phorbol ester mediated tumor promotion and carcinogenesis. Both the phorbol esters and bryostatins target PKC although they induce different activities presumably through differential modulation of PKC isoforms. Phorbol esters are tumor promoters while bryostatin is not and appears to block many of the activities of the phorbol esters.

Scheme 55.

Translating Nature’s Library: Computer Assisted Design of the First Bryostatin Analogs (Bryologs)

As might be expected from the previous FOS analysis, we saw at the outset of our studies in the mid 1980s, an opportunity to use our proposed model for phorbol ester PKC binding to identify the structural features in bryostatin that might contribute to its activity. This information would then be used to design simpler bryostatin analogs, since dubbed “bryologs”, that would be more synthetically accessible and potentially offer superior activity as well as tunability. A major problem with bryostatin is its supply.161 Fourteen tons of Bugula neritina, the marine source organism, were required to produce only 18 grams of pure compound, which has supplied all clinical and pre-clinical trials since its isolation. We started on this FOS path before total synthesis studies were initiated, but this FOS effort anticipated that realizing a practical total synthesis might take time. At present, seven total syntheses of natural bryostatins have been reported by the groups of Masamune, Evans, Yamamura, Trost, Keck, Krische, and Wender.162 The first total syntheses weighed in with total step counts in the 79–89 step range. Importantly, they provided a foundation for subsequent syntheses that have now lowered the step counts to 37–63 steps. With these advances and further improvement in methodology, this step count can be expected to further improve. Alternatively, and more importantly, since the natural products themselves are not evolved for human therapeutic use, it is clear that they might not be the optimal target but rather a starting inspiration for an FOS approach to new and better agents.

Following our proposed computer derived pharmacophore model for bryostatin,163 we designed and subsequently prepared the first non-natural bryostatin analog (bryolog 248) in 1998. Because the affinity-determining features of bryostatin were proposed to be largely localized in the C-ring region, we took the liberty in this first generation approach to eliminate features of the molecule that would simplify its synthesis without sacrificing its activity. The Cring was retained as it is proposed to contact the PKC surface. A highly simplified A- and B-ring subunit was used to conformationally control this C-ring recognition domain (Scheme 55). We used a dioxane surrogate for the B-ring pyran. This allowed for a highly convergent design in which the target is produced from two simpler fragments coupled initially through a Yamaguchi esterfication and then through a little exploited but mild macrotransacetalization (Scheme 56). The first analog synthesized based on these design elements exhibited remarkably encouraging activity, binding to PKC with nanomolar affinity and inhibiting the growth of human cancer cell lines at levels comparable to and for certain cell lines significantly better than bryostatin. The latter study conducted by the National Cancer Institute was so striking that the compounds were re-tested and again showed superb potencies. It is noteworthy that the syntheses of these designed analogs weighed in at under 30 steps at a time when the reported total syntheses required 79–89 steps. This 1998 advance showed clearly what we had proposed earlier that better analogs could be prepared and accessed in a step economical way, opening the door for us and others to now advance this promising field.

Scheme 56.

FOS: The First Designed Bryostatin Analogs – Step Economical Synthesis and Superior Function