Background: Alginolytic systems from marine bacteria are crucial for algal biomass conversion, yet their molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood.

Results: Structural and biochemical characterization of two paralogous marine alginate lyases highlights details on complementary roles and differences with terrestrial enzymes.

Conclusion: Bacterial alginolytic enzymes are specifically adapted to the unique characteristics of the natural substrate.

Significance: Marine microbes evolved complex degradation systems targeting habitat-specific polysaccharides.

Keywords: Carbohydrate Metabolism, Enzyme Mechanisms, Enzyme Structure, Evolution, X-ray Crystallography, Marine Origin

Abstract

Cell walls of brown algae are complex supramolecular assemblies containing various original, sulfated, and carboxylated polysaccharides. Among these, the major marine polysaccharide component, alginate, represents an important biomass that is successfully turned over by the heterotrophic marine bacteria. In the marine flavobacterium Zobellia galactanivorans, the catabolism and uptake of alginate are encoded by operon structures that resemble the typical Bacteroidetes polysaccharide utilization locus. The genome of Z. galactanivorans contains seven putative alginate lyase genes, five of which are localized within two clusters comprising additional carbohydrate-related genes. This study reports on the detailed biochemical and structural characterization of two of these. We demonstrate here that AlyA1PL7 is an endolytic guluronate lyase, and AlyA5 cleaves unsaturated units, α-l-guluronate or β-d-manuronate residues, at the nonreducing end of oligo-alginates in an exolytic fashion. Despite a common jelly roll-fold, these striking differences of the mode of action are explained by a distinct active site topology, an open cleft in AlyA1PL7, whereas AlyA5 displays a pocket topology due to the presence of additional loops partially obstructing the catalytic groove. Finally, in contrast to PL7 alginate lyases from terrestrial bacteria, both enzymes proceed according to a calcium-dependent mechanism suggesting an exquisite adaptation to their natural substrate in the context of brown algal cell walls.

Introduction

Brown algae dominate the primary production in temperate and polar rocky shores and represent a huge marine biomass. Indeed, coastal regions are considered as carbon sinks, retaining about 200·1012 g of carbon/year (1). Their cell walls include a minor fraction of crystalline cellulose and a majority of anionic polysaccharides, alginates, and sulfated fucoidans (2). Phlorotannins, which consist of halogenated and/or sulfated phenolic compounds (3, 4), and 5% of proteins (5) complete this complex supramolecular assemblage. Among these compounds, alginate can account for up to 40% of the dry weight of the algal biomass (6). This linear polysaccharide is composed of β-d-mannuronate (M)3 and its C5 epimer α-l-guluronate (G), which are arranged in three types of repeating structures as follows: poly-G stretches, poly-M stretches, and heteropolymeric random sequences (poly-MG) (7). The gelling properties strongly depend on the poly-G content of the algal polysaccharide, because these G blocks form highly viscous solutions and gels through interconnected metal ion chelation (mainly Ca2+) (8). Within the algal cell wall, the functional properties of alginate are modulated through changes in G and M content. These variations can be species-specific or depend on season and environmental conditions; however, to date only very few studies exploring such relationships are available (9–12). Phylogenomic analysis of the carbohydrate metabolism of the model brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus has revealed that brown algae horizontally acquired the alginate biosynthetic pathway from an ancestral Actinobacterium (13). Indeed, alginates are also produced as exopolysaccharides by some bacteria, such as those belonging to the genera Azotobacter and Pseudomonas (14, 15). The main differences at the molecular level between algal and bacterial alginates are the presence of O-acetyl groups at C2 and/or C3 in the bacterial alginates (7, 16) and their higher proportion of M units. From an ancestral bacterial exopolymer, alginate further evolved in brown algae into a pivotal cell wall polysaccharide, which is constrained by the necessity to interact with other cell wall components (2, 13). These evolutionary constraints likely explain the loss of acetyl groups in algal alginates together with the increased importance of the G units and of their interactions with calcium ions to control gel properties. This hypothesis is consistent with the expansion of the mannuronan C5-epimerase gene families observed in the brown algae Laminaria digitata (17–19) and E. siliculosus (13).

Alginate constitutes an abundant nutrient resource for heterotrophic marine bacteria and thus in coastal ecosystems plays an ecological role similar to that of cellulosic and hemicellulosic biomass in terrestrial environments. However, the comprehension of the molecular bases for the assimilation of algal alginates by marine bacteria remains at best fragmentary. We have recently reported the first operons specific for alginate assimilation in a marine bacterium, Zobellia galactanivorans (20). This flavobacterium, which is well known to degrade sulfated galactans from red seaweeds (21–23), is also able to use alginates from brown algae as the sole carbon source (24). The alginolytic system of Z. galactanivorans encompasses seven alginate lyases (AlyA1 to AlyA7) belonging to four distinct families of polysaccharide lyases (PL (25)), families PL6, -7, -14, and -17. Although alyA1 and alyA7 are isolated genes, alyA4, alyA5, and alyA6 are transcribed on the same mRNA. alyA2 and alyA3 are localized in a large operon comprising other carbohydrate-related genes, notably a TonB-dependent receptor and its associated SusD-like protein likely involved in oligo-alginate uptake (20). Such gene organization is typically found in Bacteroidetes and is referred to as a polysaccharide utilization locus (26, 27). With the exception of alyA7, all these genes are up-regulated in the presence of alginate (20). The complexity of this degradation system questions the exact role of the different alginate lyases. Notably, is there a functional redundancy providing a robustness to this alginolytic system? Do these enzymes display distinct substrate specificities? Do they proceed by different modes of action, which could have synergistic effects? To discriminate between these hypotheses, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive, the in-depth biochemical study of these enzymes is a prerequisite.

AlyA1 is a secreted modular protein with an N-terminal carbohydrate-binding module of the family 32 (CBM32) appended to a C-terminal PL7 module, and AlyA5 is predicted to be an outer membrane lipoprotein consisting of a lone PL7 catalytic domain. Moreover, these PL7 modules are extremely divergent with only 16% sequence identity, and several large insertions are present in AlyA5 in comparison with AlyA1 (20). We describe here the detailed study of structure-function relationships of the catalytic modules of two paralogous alginate lyases AlyA1 and AlyA5 from Z. galactanivorans, by a combination of crystallographic and biochemical approaches, including reaction product analysis by NMR spectroscopy.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Substrate Materials

Sodium alginate samples with three different M/G ratios (0.5, 0.9, and 2.0) were provided by Danisco. Fractions of oligoguluronates, oligomannuronates, and mixed MG oligosaccharides were prepared according to Haug et al. (9). This method has been reported to yield fragments with DP ranging from 4 to ∼30 (28). Their respective M/G composition was controlled by NMR (data not shown).

Reduction of Oligoguluronates

Oligosaccharides were reduced following a protocol adapted from Abdel-Akher and Sandstrom (29). Briefly, 3 mg of sodium borohydride were added to 500 μl of oligoguluronates (1 mg·ml−1), and the mixture was incubated overnight at room temperature. The reaction was acidified by adding drops of acetic acid until no more H2 production was observed. The sample was then dried under vacuum and resuspended in 1 drop of 17.5 m acetic acid and 1 ml of methanol. Solvent was evaporated under a nitrogen flux. The amount of reducing ends was estimated by the ferricyanide assay (30) using a calibration curve with 20–400 μg·ml−1 glucose. Before the treatment, the ferricyanide assay measured 29.4 μg·ml−1 eq·glucose in the oligoguluronate solution. No reducing ends could be detected by the same assay after the reduction.

Phylogenetic Analyses

Members of the PL7 family were selected in the CAZY database (31), and their sequences were aligned using MAFFT with the L-INS-i algorithm and the scoring matrix Blosum62 (32). The alignment was manually edited in MEGA 4.1 (33). 180 sites were used to derive a phylogenetic tree using a maximum likelihood method conducted with the PhyML program (34) implemented online on Phylogeny.fr (35). Bootstrap values were calculated from 100 resamplings of the dataset.

Cloning of Two Genes Coding for PL7 Alginate Lyases

Primers were designed to amplify the coding region corresponding to the mature protein for AlyA5 and for the catalytic module of AlyA1 only, hereafter called AlyA1PL7. The genes were amplified by PCR from Z. galactanivorans genomic DNA using the oligonucleotide primers as follows: forward ggggggGGATCCtgtaaagacaaacctaaggccactacg and reverse ccccccGAATTCtcactgggcttctggggcgcttc for AlyA5; forward ggggggAGATCTtccggtggttcgtccacccttc and reverse ccccccGAATTCttaattgtgggttacgcttaggtttttg for the catalytic domain of AlyA1PL7. Using the restriction sites EcoRI and BamHI for AlyA5, and EcoRI and BglII for AlyA1PL7, the PCR products were then ligated into the expression vector pFO4, resulting in a recombinant protein with an N-terminal hexa-histidine tag. The plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) expression strains. All cloning procedures were performed as described in Groisillier et al. (36).

Protein Expression and Purification Procedures

For both enzymes, the same procedure was applied. Two-milliliters pre-cultures of the recombinant E. coli BL21(DE3) cells were grown overnight at 37 °C in LB medium containing ampicillin (100 μg.ml−1). 200 ml of autoinducible ZYP medium with ampicillin (37) were inoculated with 200 μl of pre-culture and incubated for 3 days at 20 °C and 200 rpm. Cells were centrifuged for 20 min at 5000 rpm at 4 °C, and pellets were stored at −20 °C. Cells were resuspended in 20 ml of Buffer A (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, 5 mm imidazole) containing a mixture of antiproteases (Complete EDTA-free, Roche Applied Science) and DNase. Cells were lysed with a French press. Samples were then centrifuged for 2 h at 20,000 × g. The supernatant was loaded on a Hyper Cell PAL column charged with 0.1 m NiSO4 and equilibrated with Buffer A. Proteins were eluted with a linear gradient between Buffer A and Buffer B (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, 1 m imidazole) in 60 ml at a flow rate of 1 ml·min−1 and collected in fractions of 1 ml. Fractions showing the presence of the recombinant proteins by SDS-PAGE were pooled. Aliquots of 5 ml were further purified on a size exclusion chromatography column (Superdex 75 16/60 pg, GE Healthcare) using Buffer C (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl) at a flow rate of 1 ml·min−1. Fractions showing the presence of the pure proteins were pooled for AlyA1PL7 (data not shown), although two samples, separating the fractions of monomeric and dimeric forms of AlyA5 (data not shown), were prepared. Dynamic light scattering measurements were performed on 40 μl of concentrated protein solutions (>1 mg·ml−1) in a quartz cuvette on a ZetaSizer Nano-S instrument (Malverne Instruments).

Enzymatic Assays

Protein concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm. Theoretical molar extinction coefficients ϵ280 were computed from the protein sequences on the ProtParam server. Alginate lyase activity was assayed by measuring the increase in absorbance at 235 nm (A235) of the reaction products (unsaturated uronates) for 5 min in a 1-cm quartz cuvette containing 0.5 ml of reaction mixture in a thermostated spectrophotometer. One unit of activity was defined as an increase of 1 unit in A235 per min.

The effects of temperature, NaCl, and chelating agents on AlyA1PL7 activity were tested in 100 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, using sodium alginate 0.05% as substrate and 5 μl of purified enzyme at 1.2 μm. The chelating agents EDTA or EGTA were either incubated at 1 mm final concentration with AlyA1PL7 (overnight, 4 °C) or added directly in the reaction mixture. The effect of pH on AlyA1PL7 activity was tested using various buffers at 100 mm: citrate, pH 3.0–6.0, MOPS/NaOH (MOPS, pH 6.0–7.9), HEPES, pH 7.0–8.0, Tris-HCl, pH 7.0–8.5, and glycine-NaOH, pH 8.5–10.0. Kinetic parameters were determined at 30 °C in 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, with 10 alginate concentrations ranging from 0.075 to 2.5 mg·ml−1. Substrate concentrations were derived from the molecular mass of an M or G monosaccharide (194 g·mol−1). Reactions were performed in triplicate. A molar extinction coefficient ϵ = 8500 liter·mol−1·cm−1 (38) was used for the reaction products (unsaturated uronic acids) The kinetic parameters were estimated by a hyperbolic regression algorithm with Hyper32.

AlyA5 enzymatic assays on alginate polysaccharides were conducted as for AlyA1PL7, using 5 μl of the purified enzyme at 2.7 μm. Reactions on saturated or unsaturated oligosaccharides were performed at 30 °C in 100 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, 4 mm CaCl2, 50 μg of substrate, and 5 μl of enzyme at 5.6 μm.

Carbohydrate Electrophoresis (C-PAGE)

After enzymatic degradation, aliquots were boiled for 10 min before analysis. Oligosaccharides were analyzed by C-PAGE. Aliquots (5 μl) were mixed with 15 μl of loading buffer (10% sucrose and 0.01% phenol red). 5 μl were electrophoresed through a 6% (w/v) stacking and a 28% running, 0.75-mm thick, polyacrylamide gel in 50 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm EDTA buffer, pH 8.7. Gels were stained with Alcian blue 0.5% (w/v) followed by silver nitrate 0.4% (w/v) (73, 74). The coloration was developed with 7% sodium carbonate (w/v) containing formaldehyde, and the reaction was stopped by adding concentrated acetic acid.

Monitoring of Alginate Lyases Reaction by 1H NMR

The action of alginate lyases was directly followed at 30 °C in the NMR tube on crude alginates, G-, M-, and alternating MG blocks. The substrates were dissolved at a concentration of 5 mg·ml−1 in a 100 mm deuterated phosphate buffer, pH 7.6, with 200 mm NaCl and 5 mm CaCl2. The NMR experiments were performed on a Bruker DRX-400 MHz spectrometer using a 5.0-mm 1H/13C/15N/31P QNP probe or on a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz spectrometer using a 5.0-mm 1H/13C/15N/31P inverse detection QXI probe, and a 2.5-mm 1H/13C inverse detection probe, all equipped with z-gradients and controlled by Topspin 1.3 and 2.1 software, respectively. The 1H NMR experiments were recorded at 30 and 70 °C using a spectral width of 3000 Hz, an acquisition time of 5.62 s, a pulse width of 8.5 μs, a relaxation delay of 4 s, and 128 scans. The residual HOD signal was suppressed using the NOESY pre-saturation pulse sequence in which saturation was applied during the relaxation delay of 4 s and the mixing time of 50 ms.

Prior to an enzymatic reaction, a reference spectrum of the substrate was acquired. The sample was then removed from the probe; the enzyme was added at the proper concentration, and the tube was put back into the probe. The reaction was monitored as a function of time. To monitor the progress of degradation of the sample, series of 1H NMR spectra were recorded at 30 °C using the multizg or multizgvd programs from the Bruker library.

Analysis of End Products by NMR and Mass Spectrometry

The enzymatic degradation was performed on 10 ml of 5 mg·ml−1 alginate samples with addition of alginate lyases from Z. galactanivorans at 30 °C for 18 h. The samples were then centrifuged; the supernatant was lyophilized and dissolved in 0.1 m ammonium acetate.

The oligouronates were fractionated according to their size by preparative gel filtration chromatography on a ÄKTA system with a 16·60 Superdex 30 column (Amersham Biosciences). Oligosaccharides were eluted with 0.1 m ammonium acetate at a flow rate of 0.8 ml·min−1 at room temperature. Unsaturated oligo-alginates were detected by A235, and the relative amounts of the different end products were determined as the peak area. The fractions belonging to the same peak were pooled, lyophilized, and purified further by repeating the size exclusion chromatography procedure on the Superdex 30 column. The pure fractions were lyophilized and analyzed by ESI-MS using a Bruker Esquire-LC mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics Inc., Billerica, MA). The samples were dissolved in 1:1 MeOH-H2O and were directly injected into the electrospray with a flow of 2 μl·min−1. The mass range scanned was from 100 to 1100 atomic mass units. All acquisitions were recorded in both negative and positive mode and treated by Bruker Daltonics Esquire LC 4.5, data analysis version 3.0. To determine the structure of the end products, the oligosaccharide signals were assigned from one-dimensional proton and selective CSSF TOCSY with Keeler filter (selcssfdizs.2) from Bruker library NMR spectra and from two-dimensional 1H-1H TOCSY NMR experiments using a mixing time of 90 ms. The NMR spectra were referenced at 30 °C using acetone (δH 2.225, δC 31.05) as internal reference.

Protein Crystallization and Three-dimensional Crystal Structure Determination

The first crystallization screening experiments for both the catalytic domain of AlyA1PL7 and the full-length dimeric sample of AlyA5 were carried out at 292 K with the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method in 96-well Corning plates (catalog no. 3551). The crystallization screening was performed with JCSG+ and PACT screens from Qiagen, which makes a total of 192 conditions in two 96-well plates. A crystallization robot (Proteomics Solutions, Honeybee) was used for dispensing the drops that contained 300 nl of protein solution that were mixed with 150 nl of reservoir solution. After visual identification of initial crystallization conditions, these were further optimized in 24-well Linbro plates by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method. For AlyA1PL7, optimal conditions were obtained for a protein solution of 11.3 mg·ml−1 concentration supplemented with oligoguluronate (0.1 mg·ml−1). Drops of 2 μl volume of this protein solution were mixed with 1 μl of crystallization solution that contained 0.2 m KSCN and 28% PEG-MME 2000 and equilibrated against a reservoir containing 500 μl. For AlyA5 (dimer) the optimized conditions were obtained for a protein solution of 7.7 mg·ml−1. Drops of 2 μl volume of this protein solution were mixed with 1 μl of crystallization solution that contained 22% PEG 3350 and 0.2 m sodium/potassium tartrate and equilibrated against a reservoir containing 200 μl. The native crystals of both alginate lyases were flash-frozen at 100 K in a crystallization solution supplemented with 10% glycerol. Data were collected to 1.43 Å resolution for AlyA1PL7 and 1.75 Å for AlyA5 on beamline PROXIMA-1 equipped with an ADSC Quantum Q315r detector (SOLEIL, St Aubin, France) and a wavelength of 0.98 Å. All data sets were treated, scaled, and converted with the program suite XDS (39). The three-dimensional structures were solved by the molecular replacement method with ALY-1 from Corynebacterium sp. (PDB 1UAI) for the crystals of AlyA1PL7 and A1-II′ from Sphingomonas sp. A1 (PDB 2Z42) as initial model, in the case of AlyA5. The starting phases were optimized using the programs ARP/wARP (40) and REFMAC 5 (41) as part of the CCP4 suite (42). The refinement was carried out with REFMAC 5 and the final model building with Coot (43). Water molecules were added automatically with REFMAC-ARP/wARP and visually verified. In all cases, the stereochemistry of the final structure was evaluated using PROCHECK (44). The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3zpy and 4be3) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic Analysis

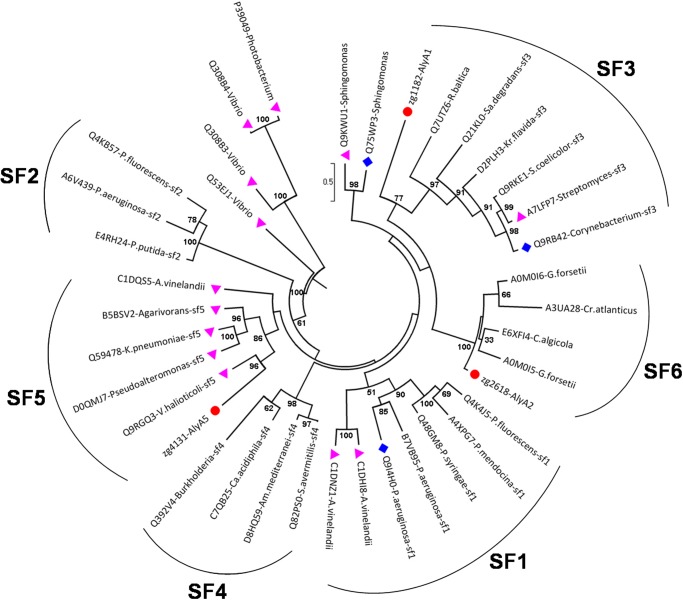

The PL7 family has been recently subdivided in subfamilies based on sequence similarities (25). To identify the subfamily for the three PL7 enzymes AlyA1, AlyA2, and AlyA5 from Z. galactanivorans, 35 additional selected sequences from the same family were used to derive a phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1). This approach clearly distinguished the five existing subfamilies within the PL7 family (SF1–SF5). It reveals that the three PL7 enzymes encoded in the Z. galactanivorans genome belong to different subfamilies. AlyA1 is distantly related to enzymes classified in SF3 and thus is a new member of this subfamily. AlyA5 can also be confidently assigned to SF5. AlyA2 was found to belong to a well supported group composed of four other enzymes from marine Flavobacteriaceae. A condition imposed by Lombard et al. (25) when creating subfamilies was that the group contained at least five members. Thus, we propose that AlyA2 and the four other enzymes in the same group belong to a new subfamily of PL7. This new subfamily, which we hereby define as SF6, appears to be conserved only in marine representatives of the Flavobacteriaceae, possibly representing a niche-specific evolution of PL7 enzymes. As subfamilies correlate in general with substrate specificities, they can help predict the preferred substrate of new enzymes (25). To date, two alginate lyases have been characterized in SF3 and seven in SF5 (CAZY database, December 2012). They all are classified as poly(α-l-guluronate) lyases (EC 4.2.2.11). Thus, we hypothesize that AlyA1 and AlyA5 should preferentially cleave G motifs (Fig. 2). No prediction can be made on AlyA2 specificity, because none of the proteins belonging to this new subfamily SF6 has yet been characterized.

FIGURE 1.

Unrooted phylogenetic tree of 38 enzymes of the PL7 family. This phylogenetic tree was calculated by the maximum likelihood approach with the program PhyML (34). Uniprot accession numbers are given. Numbers indicate the bootstrap values in the ML analysis. Values lower than 30 were not indicated. Red dots indicate enzymes from Z. galactanivorans. Pink triangles indicate enzymes characterized biochemically. Blue squares indicate that the structure of the protein has been solved. SF, subfamily. A, Azotobacter; Am. Amycolatopsis; C, Cellulophaga; Ca, Catenulispora; Cr, Croceibacter; G, Gramella; K, Klebsiella; Kr, Kribbella; P, Pseudomonas; R, Rhodopirellula; S, Streptomyces; Sa, Saccharophagus; V, Vibrio.

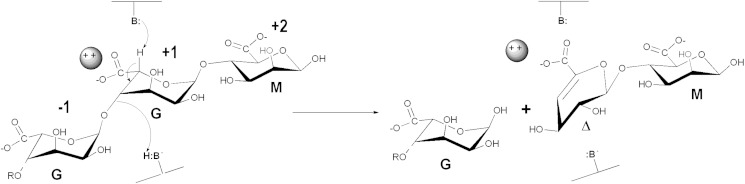

FIGURE 2.

Schematic representation of the catalytic mechanism of G-specific alginate lyases. The catalytic mechanism in G-specific alginate lyases is postulated to be an anti-elimination. The polysaccharide is cleaved to produce a 4-deoxy-l-erythro-hex-4-enepyranosyluronate moiety (Δ) at the newly formed nonreducing end of the chain; due to loss of the asymmetric center at C-4 and C-5; guluro- or mannurono-configured substrates yield essentially the same product (depending on the stereochemistry at C-1). As a prelude to chain scission, the C-5 proton adjacent to the carbonyl group is abstracted by a suitably poised basic amino acid side chain (B:). Departure of the glycosidic oxygen is likely to be facilitated by proton donation from a catalytic acid (B:H). Coordinating and charge-stabilizing cations, Ca2+, or a positively charged amino acid side chain are also a common feature of PL active sites.

Overexpression and Purification of AlyA1PL7 and AlyA5

To characterize the enzymatic activities and structural properties of the new PL7 enzymes from Z. galactanivorans, the coding sequences of the mature proteins (full-length for AlyA2 and AlyA5 and only the catalytic module for AlyA1) were cloned into pFO4 expression vector. Expression tests in E. coli BL21(DE3) grown in ZYP medium (37) were successful for the recombinant proteins AlyA1PL7 and AlyA5 but failed for AlyA2 (data not shown). We thus focused on the study of AlyA1PL7 and AlyA5. High amounts of soluble recombinant proteins were obtained and purified to homogeneity using a nickel affinity chromatography followed by gel filtration. The two steps of purification yielded 30 mg of recombinant AlyA1PL7 from 200 ml of ZYP medium. The apparent molecular mass was between 26.5 and 29 kDa (estimated from the calibration of the size exclusion column and the SDS-PAGE, respectively). This is concordant with the theoretical molecular mass of 27.5 kDa calculated for the protein sequence of the catalytic domain using ProtParam implemented in the ExPASy Proteomics Server (45). The recombinant AlyA5 eluted from the final size exclusion chromatography as two distinct peaks (data not shown), corresponding to apparent molecular masses of 69.5 and 38.3 kDa. SDS-PAGE analyses showed that these two populations contained only one protein form under denaturing conditions, with an apparent molecular mass of 42 kDa. Compared with the theoretical molecular mass of 38.3 kDa, the proteins eluted in the first and second peaks correspond roughly to a dimer and a monomer of AlyA5, respectively. This was confirmed by the difference in radius of gyration that was measured by dynamic light scattering as 2.5 and 3.2 nm for the mono-disperse samples of purified monomeric and dimeric forms of AlyA5, respectively. The purification of the recombinant AlyA5 yielded 2.2 mg of monomeric form and 10 mg of dimeric form from cultures of 200 ml. The dimeric form was stable in solution, as it eluted as a single peak after a second size exclusion chromatography, corresponding to a molecular mass of 69.5 kDa (data not shown).

Characterization of the Recombinant AlyA1PL7

Biochemical Properties of AlyA1PL7

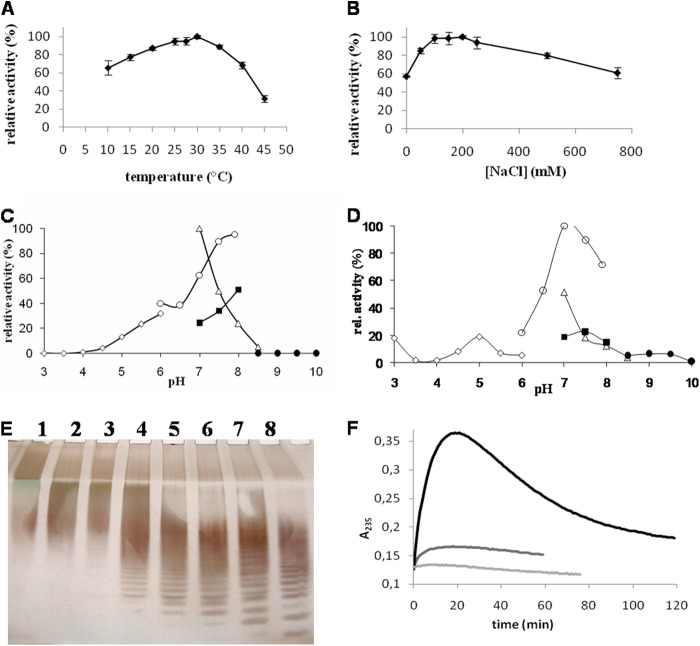

The action of the recombinant catalytic domain of AlyA1PL7 on alginate induced a strong increase in the absorbance at 235 nm, confirming that it is an alginate lyase acting via the β-elimination mechanism, producing the 4,5-unsaturated 4-deoxy-l-erythro-hex-4-enepyranosyluronate (Δ) on the nonreducing end (Fig. 2). The optimal temperature and salinity were 30 °C and 200 mm NaCl, respectively (Fig. 3, A and B). AlyA1PL7 showed the highest activity at pH 7.0 in Tris-HCl buffer (Fig. 3C). This is similar to the optimal pH determined for other alginate lyases from marine bacteria (46). No activity was detected outside the range of pH 4.0–8.5. The choice of the buffering molecule appeared to be critical, as exemplified by the 40% decrease in activity in MOPS buffer at pH 7.0 compared with Tris-HCl. Addition of the chelating agents, EDTA or EGTA, in the reaction mixture reduced the enzyme activity by 90 and 95%, respectively (data not shown). This inhibition was only incomplete when the chelating agents were incubated with the enzyme overnight but not added to the reaction mixture (43 and 58%, respectively). This suggests that the interaction between the enzyme and divalent cations takes place during substrate fixation and not before. To determine the mode of action of AlyA1PL7, the products resulting from the degradation of alginate were sampled periodically and analyzed by C-PAGE. After 2 min, the polysaccharide fraction was already largely degraded (Fig. 3E). Following the reaction from 2 min to 14 h, the size of the detected oligosaccharides decreased with time, rapidly reaching the smallest DP of 2. The appearance of intermediate larger oligosaccharides, DP4 to DP20, at early stages demonstrates that AlyA1PL7 was acting with an endolytic mode on alginate.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of temperature (A), concentration of NaCl (B) and pH (C) on AlyA1PL7 and pH (D) on AlyA5 activity, C-PAGE analysis of AlyA1PL7 degradation products (E) and degradation kinetics of alginate by AlyA5 (F). A and B, experiments were conducted in Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, using sodium alginate 0.05% as substrate and 12 nm of the purified enzyme. Values are mean ± S.D. (n = 3). A, effect of temperature. Activity at 30 °C was taken as 100%. B, effect of [NaCl]. Reactions were conducted at 30 °C. Activity with 200 mm NaCl was taken as 100%. C, effect of pH on AlyA1PL7 activity. Experiments were undertaken at 30 °C in 100 mm buffer using sodium alginate 0.05% as substrate and 27 nm of the purified enzyme. Sodium citrate (open rhombuses), MOPS (open circles), Tris-HCl (open triangles), HEPES (closed squares), and glycine-NaOH (closed circles) buffers were used in the assay. Activity in Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, was taken as 100%. D, effect of pH on AlyA5 activity. Experiments were done as above except that the protein concentration of purified AlyA5 was 56 nm. Activity in MOPS, pH 7.0, was taken as 100%. E, reaction was conducted at 30 °C in 100 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, using sodium alginate 0.05% as substrate and 12 nm of the purified enzyme. Aliquots were sampled before adding the enzyme (lane 1) and after 2 min (lane 2), 5 min (lane 3), 10 min (lane 4), 30 min (lane 5), 1 h (lane 6), 2 h (lane 7), and 14 h (lane 8). F, degradation kinetics of G (black), MG (dark gray), and M blocks (light gray) by AlyA5. A235 was measured at 30 °C for reaction mixtures (500 μl) composed of 100 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, 4 mm CaCl2, 50 μg of substrate, and 27 nm of enzyme.

Substrate Specificity of AlyA1PL7

The enzyme activity was measured on three polymeric alginate substrates, chosen for their difference in the M/G ratio. The kinetic parameters were clearly correlated with the guluronate content of the substrate. The Km value determined on G-rich alginate samples was 4-fold lower than on M-rich alginate samples, whereas the inverse relation is true for kcat/Km (Table 1). This suggests that AlyA1PL7 preferentially cleaves G stretches. The substrate specificity was then determined by carrying out the enzymatic reaction directly in the NMR tube. The 1H NMR chemical shifts were assigned according to previously published data on alginate poly- and oligosaccharides (47–51). The structure of the reducing end sugar can be easily identified by the characteristic chemical shift of its anomeric proton signal. Thus, lyase activity on a G-M or G-G diad will lead to the appearance of a doublet at 4.70–4.75 ppm with 3JHH = 8.6 Hz corresponding to the β-anomeric proton of a G residue. A lyase activity on M-M or M-G diads will give a signal at 4.75–4.80 ppm with a 3JHH <2 Hz corresponding to the β-anomer of an oligomer formed by the cleavage of such a diad. Fig. 4 shows that when the crude alginate was submitted to the action of AlyA1PL7, the characteristic doublet of G-reducing ends, H1 at 4.74 ppm with 3JHH = 8.6 Hz, appeared in the NMR spectrum, demonstrating that the enzyme requires a G unit adjacent to the cleavage site on the nonreducing end. The chemical shifts of the protons of the unsaturated nonreducing end (further denoted as “delta” and symbolized by Δ) are dependent on the nature of the nearest sugar residue. This neighbor sugar residue can be identified from the shift of the H-4 signal of Δ. An H4(Δ) doublet at δ 5.75 ppm indicates that the neighbor is a G residue, although the chemical shift of the H-4 signal appears at 5.67 ppm if the neighbor to the unsaturated nonreducing end is an M residue. As shown in Fig. 4, the intensity of the H4ΔG signal is much higher than that of H4ΔM, indicating that ΔG(X)nG oligosaccharides with X being a G or M sugar are predominantly formed by AlyA1PL7.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters of AlyA1PL7 activity on alginate with different guluronate contents

| Guluronate content in alginate | Km | kcat | kcat/Km |

|---|---|---|---|

| μm | s−1 | nm−1·s−1 | |

| 66.7% | 1753 | 12.66 | 7.22 |

| 52.6% | 3087 | 17.89 | 5.79 |

| 33.3% | 6180 | 19.51 | 3.16 |

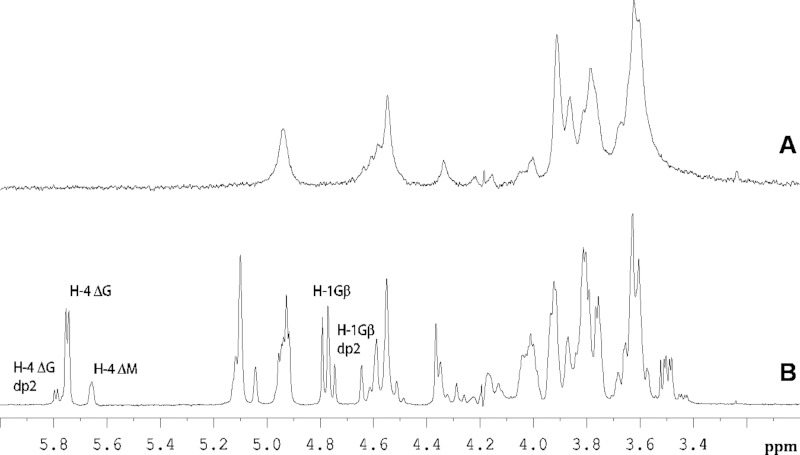

FIGURE 4.

Proton NMR spectra of alginate degradation by AlyA1PL7. Proton NMR spectra at 70 °C of 0.5-ml solutions (5 mg·ml−1 alginate in 100 mm deuterated phosphate buffer, pH 7.6, 200 mm NaCl and 5 mm CaCl2) of crude alginate, alone (A) and in the presence of AlyA1PL7 (B).

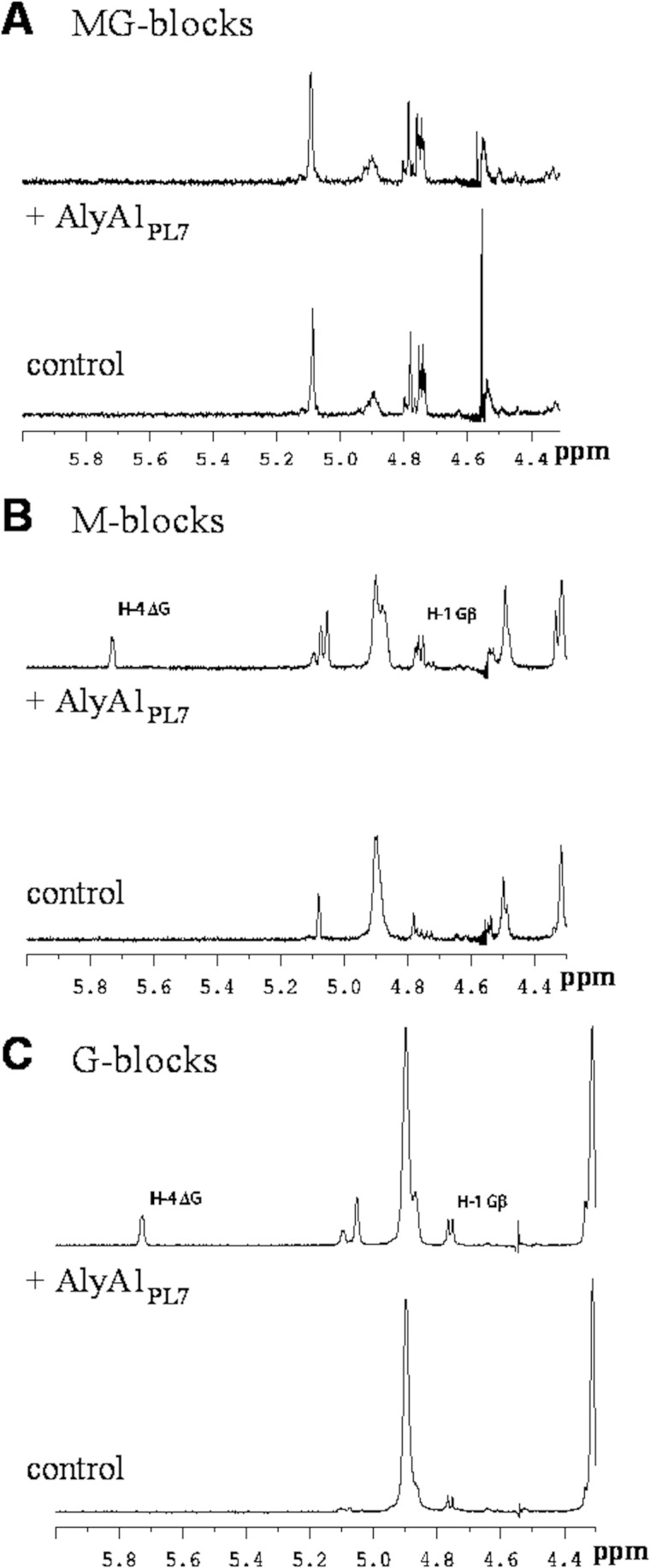

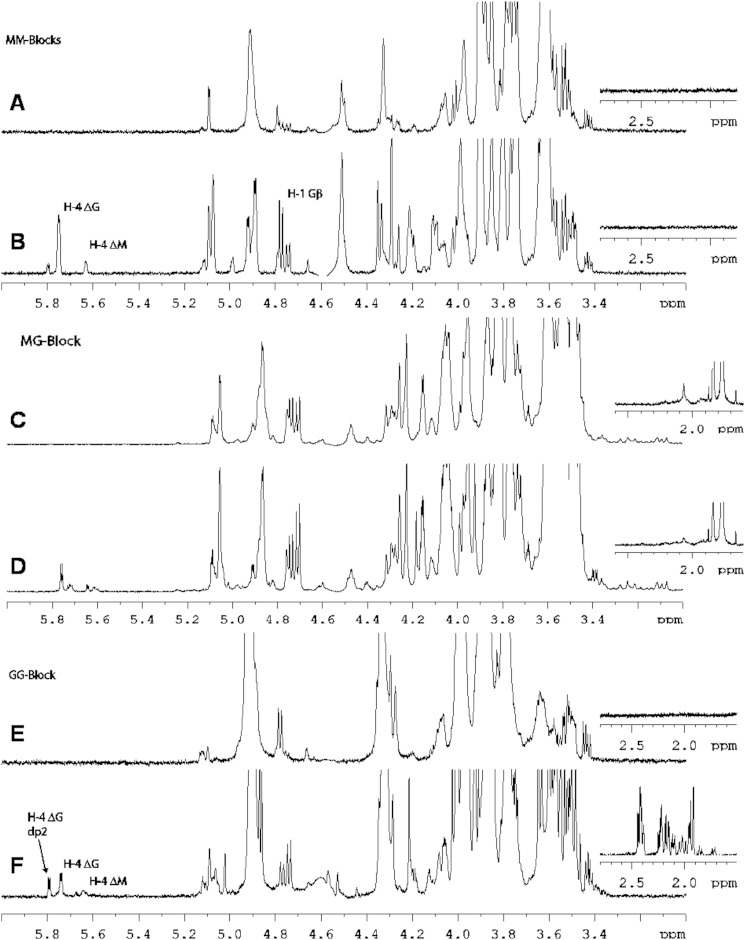

The uronic acid residue initially involved at the other end of the linkage cannot be identified from hydrolysis of crude alginate because β-elimination on β-d-mannuronosyluronate or on α-l-gulupyranosyluronate produces in both cases 4-deoxy-l-erythro-hex-4-enepyranosyluronate. Thus, to further investigate the substrate specificity of the enzyme, i.e. to determine whether AlyA1PL7 performs β-elimination indifferently on G-M and G-G diads, the degradation of poly-G, poly-M, and poly-MG purified blocks was also monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy. As shown in Fig. 5A, the spectrum of the poly-MG blocks remains unchanged, indicating that the enzyme is not active on this substrate. No cleavage is either observed for the MM diads (Fig. 5B). The minor products seen in the NMR spectrum arise from the cleavage of some GG diads present in the polymer, as demonstrated by the chemical shift of the H4Δ signal. Finally, a clear cleavage of GG blocks is observed (Fig. 5C), confirming that the enzyme cleaves only between two guluronate units of the polysaccharide chain.

FIGURE 5.

Proton NMR spectra of defined alginate samples after degradation by AlyA1PL7. Proton NMR spectra of poly-MG (A), poly-M (B), and poly-G (C) before and after incubation with AlyA1PL7.

Characterization of End Products

The oligosaccharides produced by degradation of the crude alginate with AlyA1PL7 were separated by size exclusion chromatography. The separation profile of the oligosaccharides showed three major peaks (data not shown), and the molar fractions of the different products were estimated from the size exclusion chromatography (Table 2). The ESI-MS analysis showed m/z of 351.0, 526.8, and 703.0 [M-H] indicating di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharide fragments, respectively. The lyase produced mainly trisaccharide and tetrasaccharide oligomers with a total content of 41 and 36%, respectively. Around 19% of the isolated oligomers were disaccharide and only a small amount of pentamers and hexamers were observed.

TABLE 2.

Amount of different oligosaccharides produced by AlyA1PL7 assessed by size exclusion chromatography and 1H NMR

| Oligomers | UV | NMR | Total contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlyA1PL7 | |||

| Dimers | 19% | ||

| ΔG | 100% | 19% | |

| Trimers | 41% | ||

| ΔGG | 88% | 36% | |

| ΔMG | 12% | 5% | |

| Tetramers | 36% | ||

| ΔGXG | 84% | 30% | |

| ΔMXG | 16% | 6% | |

| Pentamers | 2% | 2% | |

| Hexamers | 1% | 1% | |

| >dp6 | 1% | 1% |

The uniformly sized fractions were not separated further, and the structure and amount of the oligosaccharides present in each fraction were determined by NMR. The NMR spectrum of the disaccharide fraction showed that only ΔG was produced. The NMR spectra of the fraction corresponding to trisaccharides showed the existence of two products, ΔGG and ΔMG, present in amounts of 88 and 12% respectively. This was evidenced by the observation of two H4Δ signals, one at 5.75 ppm corresponding to Δ at the nonreducing end with a G neighbor and one at 5.67 ppm for Δ with an M neighbor. The H2 of G at the reducing end also has a characteristic chemical shift, depending on the neighboring sugar units, being 3.47 ppm with G as neighbor and 3.54 ppm with M. The amount of ΔGG (88%) and ΔMG (12%) was determined by integration of the H4ΔG and H4ΔM signals.

The NMR spectra of the fraction containing the tetrasaccharides also show the concomitant presence of several patterns. Three H4(Δ) signals were assigned to ΔGGX, ΔGMX, and ΔMXX, according to the value of their chemical shift at 5.74, 5.75, and 5.67 ppm, respectively. Two well separated signals were observed for the H2 G-reducing end with different neighbors, one with a characteristic chemical shift at 3.44 ppm for the reducing end with the G neighbor and 3.51 ppm for the reducing end with the M neighbor. Because only the G-reducing end sugars are present, the products are ΔGGG, ΔGMG, and ΔMXG. Also, two ΔH2M signals were observed in the selective TOCSY experiments (Fig. 6). Thus, four different tetrasaccharides are present ΔGGG, ΔGMG, ΔMGG, and ΔMMG. Integration of the H4ΔG and H4ΔM signals indicated that ΔGGG and ΔGMG together represent 84% of the total content of tetrasaccharides, whereas ΔMGG and ΔMMG account for 16% of the molecules.

FIGURE 6.

Proton NMR (TOCSY) spectra of defined tetrasaccharides and tetraoligo-alginate samples after degradation by AlyA1PL7. A, 1H NMR spectra of selective TOCSY on ΔH4(G) signal, including a magnification of the ΔH2(G) region. B, 1H NMR spectra of selective TOCSY on ΔH4(M) signal, including a magnification of the ΔH2(M) region. C, tetrasaccharide fraction containing ΔGGG, ΔGMG, ΔMGG, and ΔMMG. It is seen that two ΔH2(G) signals are present demonstrating the existence of ΔGGG and ΔGMG, in the same way the two ΔH2(M) signals show that both ΔMGG and ΔMMG are present.

Minimal Recognition Pattern of AlyA1PL7

The NMR analyses of the end products reveal a high content of di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharides and only very low contents of penta- and hexasaccharides. This would be in agreement with a minimal size of oligosaccharide recognized, bound, and cleaved by AlyA1PL7 being a pentasaccharide. Further experiments showed that at least the hexasaccharide G6 is indeed cleaved by AlyA1PL7 (data not shown), although the accumulation of tetrasaccharides in the end products indicates that these are not further cleaved. Purified pentasaccharides were not available, but their degradation pattern can be derived from the NMR analysis of the products obtained after enzymatic degradation. Accordingly, the structures of the pentasaccharides that can be cleaved by AlyA1PL7 are GGGGG, GGMGG, GGGMG, and GGMMG (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Pentasaccharides that can be cleaved by AlyA1PL7 and the possible degradation products

| Pentasaccharides | Possible degradation products | |

|---|---|---|

| GGGGG | → | ΔGGG + ΔGG + ΔG |

| GGMGG | → | ΔMGG |

| GGGMG | → | ΔGMG + ΔMG |

| GGMMG | → | ΔMMG |

Crystal Structure of AlyA1PL7

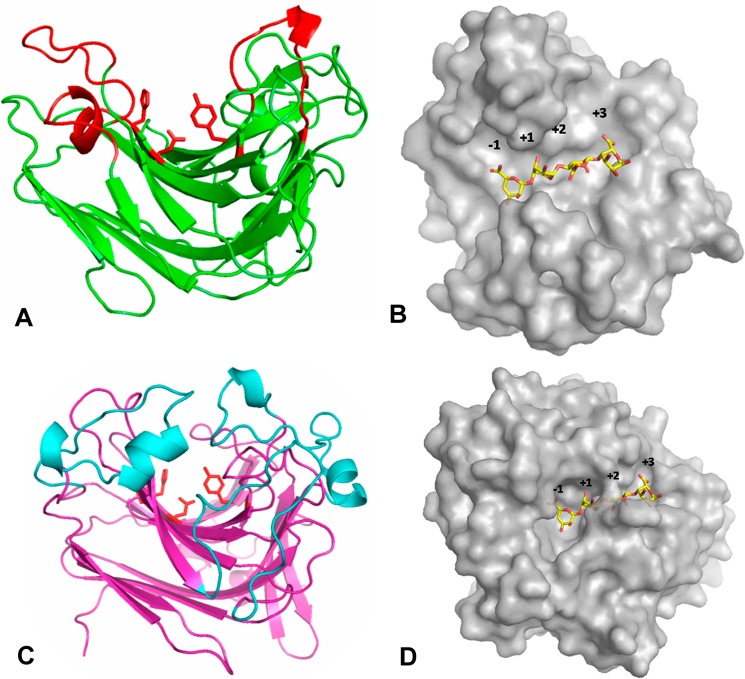

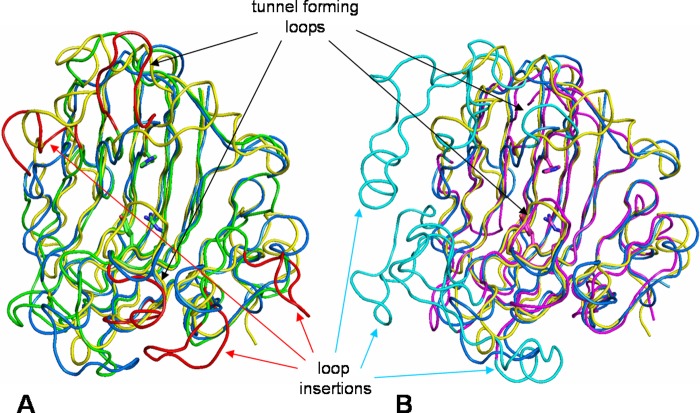

The three-dimensional crystal structure of AlyA1PL7 was determined at 1.43 Å resolution by molecular replacement (Table 4). The asymmetric unit of the triclinic unit cell contained two molecules giving rise to a global solvent content of 41%. For both molecules 248 out of 252 residues could be modeled into the electron density, with the missing residues located at the N-terminal end of the polypeptide chain. In addition, the crystal structure of AlyA1PL7 contains two calcium ions and 749 water molecules. The overall structure of AlyA1PL7 is that of a PL7 β-sandwich jelly roll-fold, formed by two anti-parallel β-sheets stacked against each other (Fig. 7A). The outer convex sheet is composed of five β-strands, and the inner concave sheet is composed of seven β-strands forming a groove that harbors the catalytic active site. Consistent with its membership in PL7_SF3, AlyA1PL7 displayed the lowest r.m.s.d. of 1.5 upon structural superimposition to Aly-1 from Corynebacterium sp. (PDB 1UAI). The structural similarity to A1-II′ from Sphingomonas sp. A1 is reflected by an r.m.s.d. of 1.76. As is typical for enzymes displaying this fold, the major structural differences are located in the flexible loops that delimit and surround the catalytic groove (Fig. 8A). In particular, and in contrast to A1-II′ from Sphingomonas sp. A1 (PDB 2ZAA), two of these loops display two short helical structures (residues Gly-265 to Asn-269 and Gly-359 to Gln-365, see Figs. 7, A and B, 8, and 9). A third loop localized between the strands β8 and β9 (Gly-324–Asp-335) is absent in the structure of Aly-1 (PDB 1UAI) and displays a largely different conformation than the equivalent loop in A1-II′, in this way participating in the open accessibility of the active site groove in AlyA1PL7 (Figs. 7A and 8A). This is in contrast to A1-II′, which displays a tunnel-shaped active site (52). Possibly, the three loops of AlyA1PL7 are trapped in an open conformation in this structure and move to form a tunnel upon substrate binding. The electron density maps defining these loops in our structure, however, are perfectly defined, and the potential flexibility of these loops thus remains an open question. At the bottom of the groove (Fig. 10A), three strictly conserved residues, Gln-321, His-323, and Tyr-420, that were reported to be involved in the lytic activity in A1-II′ from Sphingomonas sp. A1 (52) form the active site of AlyA1PL7.

TABLE 4.

Data collection and refinement statistics for the crystal structures of the native AlyA1PL7 and AlyA5

| AlyA1PL7 | AlyA5 dimer | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Beamline | PROXIMA 1 | |

| Wavelength | 0.98 Å | |

| Space group | P1 | P212121 |

| Unit cell | a = 43.86 Å; b = 50.39 Å; c = 55.52 Å | a = 93.42 Å; b = 93.91 Å; c = 130.15 Å |

| α = 69.14°; β = 90.02°; γ = 84.92° | α = β = γ = 90.00° | |

| Resolution rangea | 43.66 to 1.43 Å (1.47 to 1.43 Å) | 41.95 to 1.75 Å (1.80 Å 1.75 Å) |

| Total data | 358,902 | 967,134 |

| Unique data | 78,881 | 114,168 |

| Completeness | 96.1% (94,2%) | 99.4% (93,3%) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 14.16 (7.79) | 16.53 (2.30) |

| Rmerge | 7.8% (21.9%) | 9.6% (84.4%) |

| Redundancy | 4.55 | 8.47 |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Resolution range | 40.66 to 1.43 (1.47 to 1.43) | 41.95 to 1.80 (1.85 to 1.80) |

| Unique reflections | 74,933 (5454) | 101,057 (7343) |

| Reflections Rfree | 3944 (287) | 5319 (386) |

| R/Rfree | 14.6/20.1% (11.0/19.4%) | 15.4/17.8% (21.1/24.6%) |

| r.m.s.d. bond lengths | 0.024 Å | 0.039 Å |

| r.m.s.d. bond angles | 2.00° | 3.02° |

| Overall B factor | 12.74 Å2 | 29.16 Å2 |

| B factor, molecule A | 10.39 Å2 | 21.74 Å2 |

| B factor, molecule B | 10.32 Å2 | 21.31 Å2 |

| B factor, solvent | 25.00 Å2 | 22.67 Å2 |

| B factor, ligands | 31.56 Å2 | |

a Values in parentheses concern the high resolution shell.

FIGURE 7.

Crystal structure representations of AlyA1PL7 and AlyA5. Ribbon and surface representations of the crystal structures of AlyA1PL7 and AlyA5. A, conserved jelly roll scaffold of AlyA1PL7 catalytic module is colored in green, and the flexible additional loops are colored in red. B, surface representation of AlyA1PL7. C, conserved jelly roll scaffold of AlyA5 is colored in pink, and the additional loops are colored in blue. D, surface representation of AlyA5. A tetrasaccharide GGGG from A1-II′ was superimposed to both surface representations.

FIGURE 8.

Tube representation of the superimposition of the three-dimensional structure of PL7 alginate lyases. A, superimposition of AlyA1PL7 (green tube) onto AlyPG from Corynebacterium sp. ALY-1 (blue tube, PDB code 1UAI) and A1-II′ from Sphingomonas sp. A1 (yellow tube, PDB code 2ZAA). B, superimposition of AlyA5 (magenta tube) ontoAlyPG from Corynebacterium sp. ALY-1 (blue tube, PDB code 1UAI) and A1-II′ from Sphingomonas sp. A1 (yellow tube, PDB code 2ZAA). Loops that have different configurations or large loop insertions with respect to 1UAI and 2ZAA are highlighted by the arrows and colored in red for AlyA1PL7 and cyan for AlyA5. Residues in the colored loops all display significantly higher B-factors by 2 to 10 Å2 than the mean B-factor of the respective molecules.

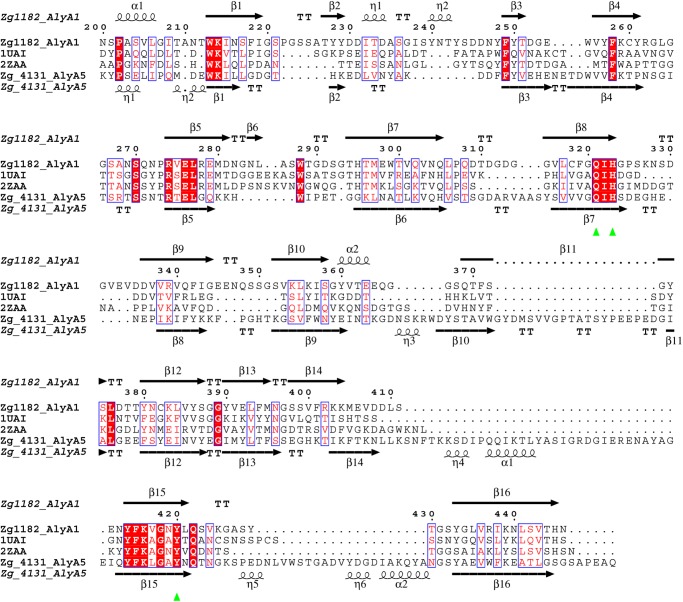

FIGURE 9.

Structure-based sequence alignment of AlyA1PL7 and AlyA5. The sequences are aligned with those from two other PL7 alginate lyases with known structure, AlyPG from Corynebacterium sp. ALY-1 (PDB code 1UAI) and A1-II′ from Sphingomonas sp. A1 (PDB code 2ZAA). The secondary structures of AlyA1PL7 and AlyA5 are shown above and below the alignment, respectively. Conserved amino acids in white letters highlighted on the red background are identical and those in red letters are similar. α-Helices are represented as schematically, and β-turns are marked with TT. Green triangles indicate the conserved residues involved in the catalytic machinery. This figure has been generated using the program ESPRIPT (72).

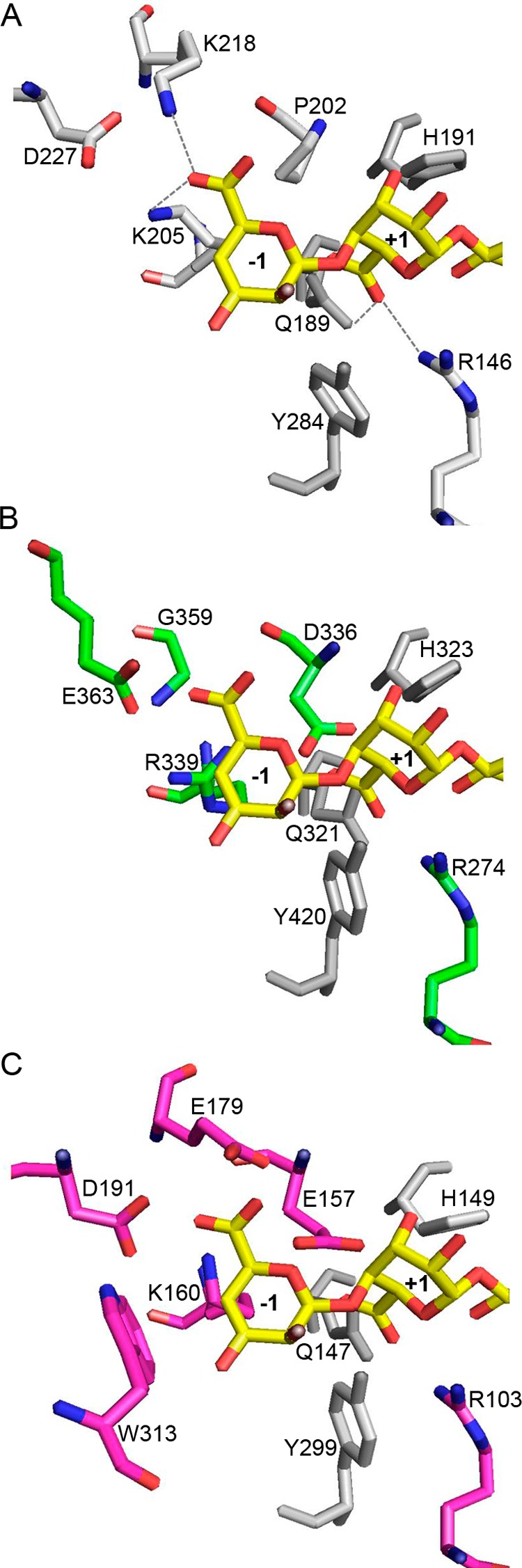

FIGURE 10.

Residues surrounding the conserved catalytic active site in AlyA1PL7 and AlyA5. Close-up view into the active site of A1-II′ (PDB code 2Z42) in complex with an oligo-guluronate tetrasaccharide (A); AlyA1PL7 (B), and AlyA5 (C). The potential positions of oligotetrasaccharide molecules were obtained by superimposition with A1-II′ in complex with substrate. The respective residues at equivalent positions are labeled. Both AlyA1PL7 and AlyA5 contain additional negatively charged residues close to the carboxylate groups of the substrate.

Characterization of the Recombinant AlyA5

Biochemical Properties of AlyA5

When the dimeric form of AlyA5 was incubated with alginate, recordings of A235 showed a kinetic in two phases (Fig. 3F). In the first phase, the absorption increased, showing that AlyA5 cleaved alginate by a β-elimination mechanism and confirming its annotation as an alginate lyase. This was followed by a decrease in A235, suggesting the transitory nature of the UV-absorbing material. Such a profile is typical for exolytic lyases producing unsaturated monosaccharides (53). Indeed, these reaction products subsequently convert nonenzymatically to the most stable 5-keto-structure, i.e. 4-deoxy-l-erythro-5-hexoseulose uronic acids (DEH), which does not absorb at 235 nm due to the transfer of the unsaturation to the ketone group (38, 54, 55). The addition of at least 2 mm Ca2+ in the reaction mixture was essential for the activity (data not shown). AlyA5 showed the highest activity at pH 7.0 in MOPS buffer (Fig. 3D) and displayed a narrow range of tolerance. The choice of the buffering molecule was critical, as exemplified by the 50% decrease in activity in Tris-HCl buffer at pH 7.0 compared with MOPS. To analyze from which end of the substrate the exolytic enzyme attacks, AlyA5 activity was monitored on poly-G blocks that had their reducing ends reduced using sodium borohydride prior to the digestion. Compared with the reaction with classical poly-G substrate, AlyA5 retained 75% of its activity on such reduced substrates, indicating that the enzyme cleaves the unit at the nonreducing end. The 25% decrease in activity can be attributed to loss of material during the successive evaporation/resolubilization steps that are part of the reduction protocol.

Substrate Specificity of AlyA5

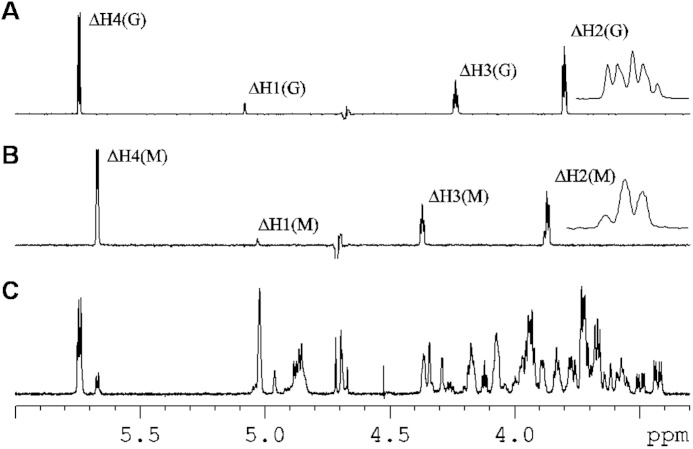

To assess the substrate specificity of AlyA5, the activity was tested on MG, M, and G blocks. The reactions were followed by the absorbance at 235 nm and by 1H NMR (Figs. 3F and 11). The three substrates were degraded, indicating that the enzyme has a broad substrate tolerance and can cleave M-M, M-G, and G-G linkages at the nonreducing end. The activity was depending on the block structure. Specific activities were calculated in the first phase of the reaction, corresponding to the increase in A235 (Fig. 3F). AlyA5 was much more active on G blocks (449.3 units·mg−1) than on MG blocks (13.5 units·mg−1) or M blocks (2.0 units·mg−1). On the NMR spectra (Fig. 11), in addition to the characteristic H4Δ signals indicating formation of unsaturated oligosaccharides, other signals were observed in the region 1.6–2.6 and 3–4 ppm (see below).

FIGURE 11.

Proton NMR spectra of alginate degradation by AlyA5. Proton NMR spectra for poly-M alone (A), poly-M in presence of AlyA5 (B), poly-MG (C), poly-MG after addition of AlyA5 (D), poly-G (E), and poly-G after addition of AlyA5 (F).

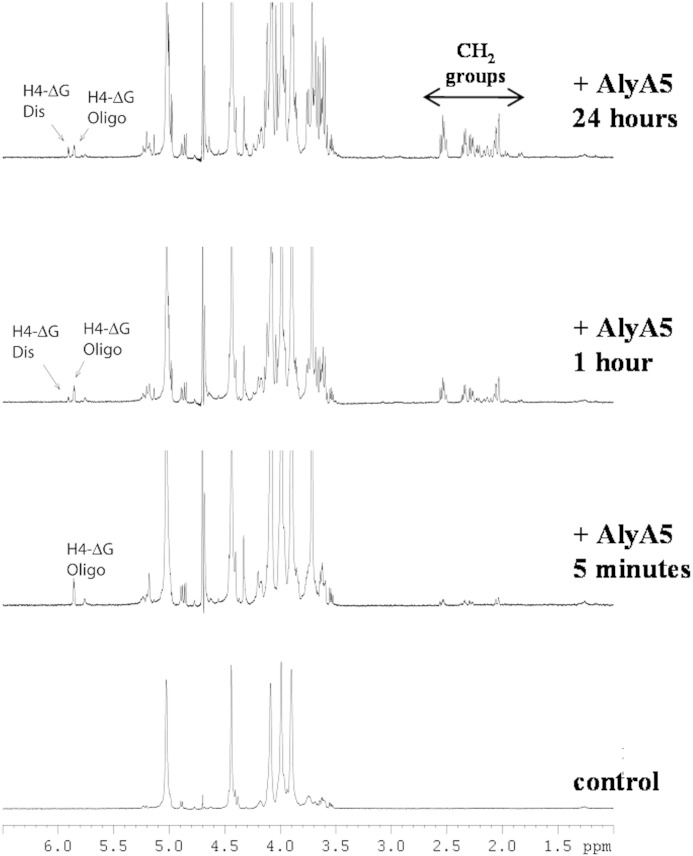

Characterization of End Products

The degradation of poly-G was followed by NMR to characterize the end products resulting from AlyA5 activity. Fig. 12 shows that during the course of the reaction, the concentration of the disaccharide ΔG increased although the concentration of the longer unsaturated oligosaccharides decreased. A small amount of the unstable Δ-(4,5)-unsaturated pyranose monomer was also identified in the NMR spectra. As the reaction progressed, signals corresponding to protons from CH2 groups appeared in the NMR spectra (Fig. 12). These proton signals have chemical shifts typical for CH2 groups close to a keto group or hemiketal (56). Thus, the NMR data confirm that one of the reaction products is DEH resulting from the spontaneous conversion of the unsaturated monosaccharide Δ. The concentration of the unsaturated disaccharide always stays low during the course of the reaction, compared with the signal intensities from DEH. This indicates that ΔG is a minor product of the degradation reaction.

FIGURE 12.

Proton NMR spectra of alginate degradation by AlyA5. 1H NMR spectra monitoring the degradation of G blocks by AlyA5 as a function of time.

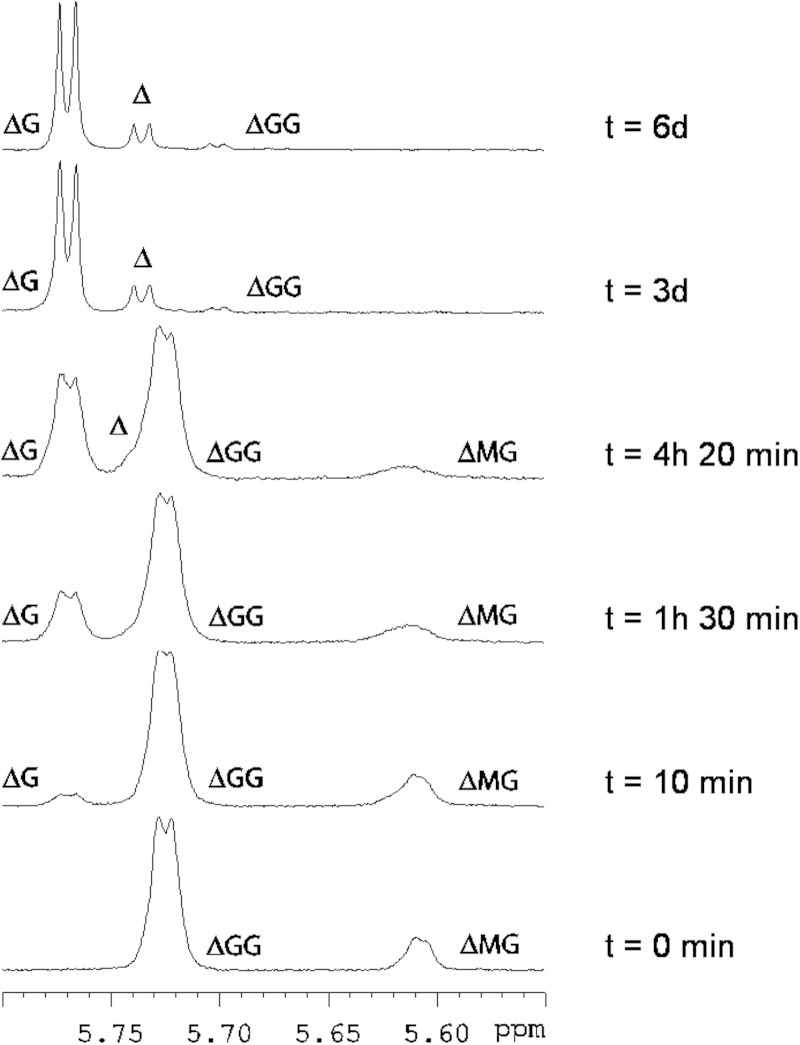

Minimal Recognition

Incubation of the unsaturated trisaccharide ΔGG with AlyA5 resulted in the formation of Δ and ΔG detected by 1H NMR (Fig. 13). The amount of ΔG was much higher than that of Δ confirming that the unsaturated monosaccharide is not stable in aqueous solution. Concordantly, signals corresponding to deoxy protons appeared in the 1.5–2.6 ppm region of the 1H NMR spectra. As seen in Fig. 13, some ΔMG was present as traces in the solution containing ΔGG. ΔMG was degraded during the course of the reaction into Δ and ΔG indicating that AlyA5 is also able to cleave the ΔM glycosidic linkage. The fact that ΔM was not observed strengthens the conclusion that AlyA5 attacks its substrate from the nonreducing end. The enzyme was also active on ΔMM producing Δ + ΔM (data not shown). The activity on ΔGM was not studied, but the combined data above suggest that this compound should also be a substrate for AlyA5. The saturated oligosaccharides MMM and GGG were also found to be substrates of AlyA5, producing ΔM and ΔG, respectively. Disaccharides were not substrate for the enzyme. Thus, the minimal recognition oligosaccharides are saturated and unsaturated trisaccharides, and the enzyme is able to cleave a G, M, or Δ unit from the nonreducing end.

FIGURE 13.

Proton NMR spectra of the degradation of a defined alginate-oligosaccharide by AlyA5. 1H NMR spectra showing the degradation of ΔGG by AlyA5 as a function of time in minutes and days (d). Only the region corresponding to unsaturated H4 protons at the nonreducing end is shown. Bottom spectra, ΔGG before addition of the enzyme.

Crystal Structure of AlyA5

AlyA5 represents the first three-dimensional crystal structure of an exolytic alginate lyase belonging to the family PL7 SF5. The structure was determined at 1.75 Å resolution, and the asymmetric unit contains two independent molecules. For both molecules, the atomic positions for 312 amino acids out of 337 residues could be constructed into the electron density, with 22 residues missing at the N-end terminal and 3 missing at the C-terminal end of the polypeptide chains. The crystal structure trapped tartrate and glycerol molecules, present in the buffer solutions, for both independent AlyA5 molecules. In addition the asymmetric unit contained 623 water molecules, equally distributed around the two alginate lyase molecules. The overall fold is very similar to that of AlyA1PL7 (r.m.s.d. between AlyA1PL7 and AlyA5 is 2.02) but is even closer to both A1-II′ (2Z42) and Aly-1 (1UAI) with an r.m.s.d. of 1.4 (Fig. 8B). The structural determinant leading to the exolytic activity can easily be identified as three large additional loops, Trp-197–Asp-217, Ser-257–Glu-284, and Gly-304–Asp-318 (Figs. 7, C and D, 8B, and 9) that close up at one end the catalytic groove of the concave β-sheet. In particular, Trp-313 is located close to the three conserved catalytic residues, Gln-147, His-149, and Tyr-299, constituting a hydrophobic wall obstructing the continuation of the groove (Fig. 10C). As a consequence, the catalytic active site of AlyA5 is located at the bottom of a pocket (Fig. 7D), in contrast to the wide-open cleft observed in AlyA1PL7. Interestingly, although our structure does not contain any bound ligand, the loop between β4 and β5 (Ser-92–Asn-101 in AlyA5, equivalent to Gly-263–Gln-271 in AlyA1PL7, Figs. 8 and 9) displays exactly the same closed tunnel conformation as the equivalent loop in A1-II′ with trapped substrate (closed form).

DISCUSSION

Heterotrophic bacteria have evolved diverse strategies to efficiently assimilate the polysaccharides available in their habitat. In general, polysaccharide degrading organisms will produce several enzymes that together, synergistically or by complementary actions, will break down the complex polymers into smaller mono- and oligosaccharide building units. These degradation products are subsequently taken up and further catabolized. A large number of studies are available on such enzyme systems for microorganisms degrading terrestrial plant cell walls. On the contrary, only few studies are available on the molecular bases of marine algal cell wall utilization. For example, work on catabolic systems targeting the polysaccharide alginate has in general focused on enzymatic pathways for the complete degradation of bacterial alginate, rather then on alginate present in the brown algal cell wall. These studies have shown that bacterial alginate breakdown by terrestrial species such as Pseudomonas sp. (38, 57), Sphingomonas sp. (58), or Agrobacterium (59) relies on a system that utilizes a particular ABC-transporter complex to channel the polymer to cytoplasmic lyases. In contrast, as evidenced by our recent study, the marine flavobacterium Z. galactanivorans produces a series of intracellular, outer membrane-bound, and secreted alginate lyases, most of which are encoded by polysaccharide utilization locus operon structures comprising SusCD-like genes coding a putative oligo-alginate import system (20). Interestingly, in the context of a bioengineering project aimed at building an E. coli strain able to produce bioethanol from brown seaweed, Wargacki et al. (60) have shown by an indirect genetic approach that the outer membrane porin KdgMN (V12B01_24269 and V12B01_309) and the sodium/solute symporter V12B01_24194 (plasma membrane) are responsible for the uptake of oligo-alginates in Vibrio splendidus 12B01, pointing toward the hypothesis that alginate uptake systems in Flavobacteriaceae and Vibrionaceae are unrelated.

Enzymes specifically recognizing and cleaving d-mannuronate or l-guluronate units in alginate have been identified in the following PL families: PL5, PL7, PL14, PL15, PL17, PL18, and PL20 (31). The substrate specificities and modes of action of these alginate lyases vary between families. Namely, the family PL14 enzyme shows a pH dependent exo- and endolytic activity (61), and the PL5 enzyme with known structure is an M-M-specific lyase that efficiently liquefies acetylated alginates (62), and the structurally characterized enzyme belonging to family PL15 cleaves off the unsaturated sugar in an exolytic manner (63). Most examples of characterized enzymes come from family PL7, where G-, M-, and MG-specific enzymes have been described (52, 64–66). Despite the wealth of biochemical data and the occurrence of numerous annotated gene sequences, only a few structural studies of alginate lyases are available. Among these structural studies, three are about family PL7 enzymes from different terrestrial bacteria (65–67). All PL7 enzymes for which structures have been determined so far are endolytic, and they randomly degrade alginate chains to produce unsaturated oligo-alginates with various chain lengths.

The genome of Z. galactanivorans contains seven putative alginate lyase genes, three of which are members of family PL7. The transcription of the PL7 coding genes (alyA1, alyA2, and alyA5) was strongly induced when Z. galactanivorans used alginate as sole carbon source (20). The phylogenetic analyses of the sequences of the three PL7 enzymes show that they fall into three distinct subfamilies, namely SF3, SF5, and the new SF6, which supports the hypothesis that these lyases play different roles and have complementary activities. In this study, the biochemical and structural characterization of two family PL7 alginate lyases from the alginolytic system of Z. galactanivorans, the secreted AlyA1PL7 and the outer membrane-bound AlyA5, reveals that at least two of these PL7 enzymes have very complementary activities.

Indeed, our results show that together and in vitro, these two enzymes can transform naturally occurring algal alginate completely into disaccharide units (ΔG or ΔM) plus the unsaturated monosaccharide that spontaneously converts into DEH.

In agreement with substrate specificities observed in PL7_SF3, AlyA1PL7 is a true G-specific, endo-acting enzyme that specifically cleaves between two G units. However, AlyA5 represents the first exolytic PL7 member so far described. Interestingly, AlyA5 appears to be able, albeit having a preference for Δ or G units, to cleave any of the three types of nonreducing ends, Δ, G, or M, from oligo-alginate chains. This versatility is rather rare among described alginate lyases, which are in general specific toward one of the three types of block-structures occurring in alginate. One other endolytic PL7 alginate lyase, A1-II′ (accession code Q75WP3, not included in any attributed subfamily, see Fig. 1), has been reported to display broad substrate specificity (68), although these two enzymes do not fall into the same subfamily (54).

Together with PL14 (61, 69), this is the second example of an alginate lyase family containing both enzymes active on polymer chains and on short oligosaccharides. This is in agreement with the general rule that endo- or exolytic activity is not defined by family membership (25) but rather by specific structural differences in loops surrounding the active site formed by the conserved scaffold. Here, large loop insertions of up to 27 residues in the sequence of AlyA5 block the catalytic groove at one end leading to a pocket architecture, whereas most of the secondary structures and residues involved in catalysis are well conserved with the other PL7 members (Fig. 9).

A superimposition of the crystal structure of A1-II′ in complex with an oligo-alginate allows positioning the substrate with respect to the catalytic residues in AlyA1PL7 or AlyA5. In AlyA1PL7, in addition to the conserved catalytic triad (Gln-321, His-323, and Tyr-420), several residues, such as Lys-214, Arg-274, Arg-278, Tyr-414, and Lys-416, take equivalent positions as those described to be in contact with the ligand molecule in the complex structure of A1-II′ (Fig. 10). The major differences between AlyA1PL7 and the A1-II′-substrate complex are as follows. First, there is no equivalent to Asn-141 (A1-II′ numbering) that is part of the first loop (residues Cys-260 to Pro-273 in AlyA1PL7; Fig. 9). Second, Gln-97 is replaced by a shorter residue, Asn-216 in AlyA1PL7, making the distance to interact with the substrate much longer. Third, in AlyA1PL7, an aspartate residue (Asp-336, absent in A1-II′) is positioned close to the catalytic active site.

But the most striking feature that differentiates AlyA1PL7 and AlyA5 from other PL7 alginate lyases is the presence of several more negatively charged aspartate and glutamate residues in the vicinity of the −1,+1 cleavage site (Fig. 10). In AlyA1PL7, the equivalent position of Pro-202 of A1-II′ (Fig. 10A) is occupied by Asp-336 (Fig. 10B), which would be both in sterical clash and electrostatic repulsion with the uronate group if the +1 G unit would bind exactly in the same position as deduced from the superimposition with A1-II′. In A1-II′, Lys-218 interacts with the G unit bound to the −1-binding site. The equivalent region in AlyA1PL7 includes strand β9 and helix α2. The corresponding strand in A1-II′ is badly superimposed with β9, and there is no equivalent of helix α2. As a consequence, the Cα of Lys-218 is roughly substituted by a glycine (Gly-359), and its side chain is spatially replaced by the acidic group of Glu-363. Again, this conformation appears incompatible with a similar binding of a G unit in −1.

In AlyA5 there are even three acidic residues that would come into sterical clash with alginate G units if bound as in A1-II′ (Fig. 10C); here, Pro-202 is replaced by Glu-157, and again the region, including Lys-218 in A1-II′, is poorly conserved, with strands β9 and β10 of AlyA5 significantly displaced in comparison with the corresponding strands in A1-II′. Thus, Lys-218 is spatially substituted in AlyA5 by a cluster of two acidic residues, Glu-179 and Asp-191, with their side chains pointing toward the carboxylic group of the modeled G unit in subsite +1. Remarkably, these residues are situated in the extended loops that are found in variable conformations in the different PL7 alginate lyase structures. In our crystal structure of AlyA5 the loops are closed above the active site groove, although closed forms in other PL7 enzymes are only observed in presence of substrate. Overall, the different loop conformations observed in the various crystal structures are indicative of flexible loops, and most probably loop movements assist substrate binding and release. Together with the finding that chelating agents inhibited the lyase activities, these structural features lead us to hypothesize that substrate binding and recognition in AlyA1PL7 and AlyA5 includes interactions mediated by calcium ions. Loop movements displacing the acidic residues together with calcium binding could bring the residues from their actual conformations into positions for productive interactions of the enzyme with its natural calcium-chelated alginate substrate. A similar substrate-binding mode, involving acidic amino acids and calcium ions to a negatively charged substrate, is observed in other polysaccharide lyases, such as chondroitin B lyase (70) and pectate lyases (71). The rationale of such a variation in the binding and recognition mode of the here studied PL7 alginate lyases, as compared with that of the previously described enzymes, would be found in the different nature of alginate originating from bacteria or from brown seaweeds. Indeed, the negative charges of algal alginates are not masked by acetyl group as in bacterial alginates. Moreover, alginate chains have multiple interactions with other cell wall compounds, polysaccharides, phlorotannins, and proteins but also inorganic ligands such as calcium or iodine ions (2, 13). In conclusion, our biochemical and structural analyses of these first marine alginate lyases demonstrate that they have indeed complementary roles in the degradation of algal alginate. Moreover, these results shed light on the molecular basis for adapted specificity and binding mode to their natural substrate. Further work is under way to confirm the hypothesis described here and to proceed with the characterization of all the other enzymatic players of the complete alginolytic system of Z. galactanivorans.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Andrew Thompson and Pierre Legrand for help and support during data collection and treatment at beamline PROXIMA 1, SOLEIL (French Synchrotron at St. Auban).

This work was supported by European Community's Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007-2013 under Grant Agreement 222628 and by the Region Bretagne and the CNRS.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3zpy and 4be3) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- M

- β-d-mannuronate

- G

- α-l-guluronate

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- C-PAGE

- carbohydrate electrophoresis

- DEH

- 4-deoxy-l-erythro-5-hexoseulose uronic acid

- PL

- polysaccharide lyase

- DP

- degrees of polymerization.

REFERENCES

- 1. Duarte C. C., Middelburg J. J., Caraco N. (2005) Major role of marine vegetation on the oceanic carbon cycle. Biogeosciences 2, 1–8 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Popper Z. A., Michel G., Hervé C., Domozych D. S., Willats W. G., Tuohy M. G., Kloareg B., Stengel D. B. (2011) Evolution and diversity of plant cell walls: from algae to flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 62, 567–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vreeland V., Waite J. H., Epstein L. (1998) Polyphenols and oxidases in substratum adhesion by marine algae and mussels. J. Phycol. 34, 1–18 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schoenwaelder M. E., Wiencke C. (2000) Phenolic compounds in the embryo development of several Northern Hemisphere fucoids. Plant Biol. 2, 24–33 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Quatrano R. S., Stevens P. T. (1976) Cell wall assembly in Fucus zygotes: I. Characterization of the polysaccharide components. Plant Physiol. 58, 224–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smidsrod O., Draget K. I. (1996) Chemistry and physical properties of alginates. Carbohydr. Eur. 14, 6–13 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gacesa P. (1988) Alginates. Carbohydr. Polym. 8, 161–182 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grant G. T., Morris E. R., Rees D. A., Smith P. J., Thom D. (1973) Biological interactions between polysaccharides and divalent cations: the egg-box model. FEBS Lett. 32, 195–198 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haug A., Larsen B., Smidsrød O. (1974) Uronic acid sequence in alginate from different sources. Carbohydr. Res. 32, 217–225 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kloareg B., Quatrano R. (1988) Structure of the cell walls of marine algae and ecophysiological functions of the matrix polysaccharides. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Ann. Rev. 26, 259–315 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Skriptsova A., Khomenko V., Isakov V. V. (2004) Seasonal changes in growth rate, morphology and alginate content in Undaria pinnatifida at the northern limit in the Sea of Japan. J. Appl. Phycol. 16, 17–21 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Craigie J. S., Morris E. R., Rees D. A., Thom D. (1984) Alginate block structure in Phaeophyceae from Nova-Scotia-Variation with species, environment and tissue-type. Carbohydr. Polym. 4, 237–252 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Michel G., Tonon T., Scornet D., Cock J. M., Kloareg B. (2010) The cell wall polysaccharide metabolism of the brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus. Insights into the evolution of extracellular matrix polysaccharides in Eukaryotes. New Phytologist. 188, 82–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ramsey D. M., Wozniak D. J. (2005) Understanding the control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate synthesis and the prospects for management of chronic infections in cystic fibrosis. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 309–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Remminghorst U., Rehm B. H. (2006) Alg44, a unique protein required for alginate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEBS Lett. 580, 3883–3888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Skjåk-Braek G., Grasdalen H., Larsen B. (1986) Monomer sequence and acetylation pattern in some bacterial alginates. Carbohydr. Res. 154, 239–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Charrier B., Coelho S. M., Le Bail A., Tonon T., Michel G., Potin P., Kloareg B., Boyen C., Peters A. F., Cock J. M. (2008) Development and physiology of the brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus: two centuries of research. New Phytologist. 177, 319–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nyvall P., Corre E., Boisset C., Barbeyron T., Rousvoal S., Scornet D., Kloareg B., Boyen C. (2003) Characterization of mannuronan C-5-epimerase genes from the brown alga Laminaria digitata. Plant Physiol. 133, 726–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roeder V., Collén J., Rousvoal S., Corre E., Leblanc C., Boyen C. (2005) Identification of stress gene transcripts in Laminaria digitata (phaeophyceae) protoplast cultures by expressed sequence tag analysis. J. Phycol. 41, 1227–1235 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thomas F., Barbeyron T., Tonon T., Génicot S., Czjzek M., Michel G. (2012) Characterization of the first alginolytic operons in a marine bacterium: from their emergence in marine Flavobacteria to their independent transfers to marine Proteobacteria and human gut Bacteroides. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 2379–2394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jam M., Flament D., Allouch J., Potin P., Thion L., Kloareg B., Czjzek M., Helbert W., Michel G., Barbeyron T. (2005) The endo-β-agarases AgaA and AgaB from the marine bacterium Zobellia galactanivorans: two paralogue enzymes with different molecular organizations and catalytic behaviours. Biochem. J. 385, 703–713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rebuffet E., Groisillier A., Thompson A., Jeudy A., Barbeyron T., Czjzek M., Michel G. (2011) Discovery and structural characterization of a novel glycosidase family of marine origin. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 1253–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hehemann J. H., Correc G., Thomas F., Bernard T., Barbeyron T., Jam M., Helbert W., Michel G., Czjzek M. (2012) Biochemical and structural characterization of the complex agarolytic enzyme system from the marine bacterium Zobellia galactanivorans. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 30571–30584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thomas F., Barbeyron T., Michel G. (2011) Evaluation of reference genes for real time quantitative PCR in the marine flavobacterium Zobellia galactanivorans. J. Microbiol. Methods 84, 61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lombard V., Bernard T., Rancurel C., Brumer H., Coutinho P. M., Henrissat B. (2010) A hierarchical classification of polysaccharide lyases for glycogenomics. Biochem. J. 432, 437–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koropatkin N. M., Martens E. C., Gordon J. I., Smith T. J. (2008) Starch catabolism by a prominent human gut symbiont is directed by the recognition of amylose helices. Structure 16, 1105–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koropatkin N. M., Cameron E. A., Martens E. C. (2012) How glycan metabolism shapes the human gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 323–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shimokawa T., Yoshida S., Kusakabe I., Takeuchi T., Murata K., Kobayashi H. (1997) Some properties and action mode of (1→4)-α-l-guluronan lyase from Enterobacter cloacae M-1. Carbohydr. Res. 304, 125–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abdel-Akher M. A., Sandstrom W. M. (1951) The abnormal reaction of glycine and related compounds with nitrous acid. Arch Biochem. 30, 407–413 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kidby D. K., Davidson D. J. (1973) A convenient ferricyanide estimation of reducing sugars in the nanomole range. Anal. Biochem. 55, 321–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cantarel B. L., Coutinho P. M., Rancurel C., Bernard T., Lombard V., Henrissat B. (2009) The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D233–D238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Katoh K., Toh H. (2008) Improved accuracy of multiple ncRNA alignment by incorporating structural information into a MAFFT-based framework. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. (2007) MEGA4: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guindon S., Gascuel O. (2003) A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52, 696–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dereeper A., Guignon V., Blanc G., Audic S., Buffet S., Chevenet F., Dufayard J. F., Guindon S., Lefort V., Lescot M., Claverie J. M., Gascuel O. (2008) Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the nonspecialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W465–W469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Groisillier A., Hervé C., Jeudy A., Rebuffet E., Pluchon P. F., Chevolot Y., Flament D., Geslin C., Morgado I. M., Power D., Branno M., Moreau H., Michel G., Boyen C., Czjzek M. (2010) MARINE-EXPRESS: taking advantage of high throughput cloning and expression strategies for the post-genomic analysis of marine organisms. Microb. Cell Fact. 9, 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Studier F. W. (2005) Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein Expr. Purif. 41, 207–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Preiss J., Ashwell G. (1962) Alginic acid metabolism in bacteria. I. Enzymatic formation of unsaturated oligosaccharides and 4-deoxy-l-erythro-5-hexoseulose uronic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 237, 309–316 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kabsch W. (2010) XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Perrakis A., Harkiolaki M., Wilson K. S., Lamzin V. S. (2001) ARP/wARP and molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57, 1445–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Murshudov G. N., Skubák P., Lebedev A. A., Pannu N. S., Steiner R. A., Nicholls R. A., Winn M. D., Long F., Vagin A. A. (2011) REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 355–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Collaborative Computational Project No. 4 (1994) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S., Wilkins M. R., Appel R. D., Bairoch A. (2005) in The Proteomics Protocols Handbook (Walker J. M., ed) pp. 571–607, Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wong T. Y., Preston L. A., Schiller N. L. (2000) ALGINATE LYASE: Review of major sources and enzyme characteristics, structure-function analysis, biological roles, and applications. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54, 289–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chavagnat F., Heyraud A., Colin-Morel P., Guinand M., Wallach J. (1998) Catalytic properties and specificity of a recombinant, overexpressed d-mannuronate lyase. Carbohydr. Res. 308, 409–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ertesvåg H., Erlien F., Skjåk-Braek G., Rehm B. H., Valla S. (1998) Biochemical properties and substrate specificities of a recombinantly produced Azotobacter vinelandii alginate lyase. J. Bacteriol. 180, 3779–3784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gimmestad M., Ertesvåg H., Heggeset T. M., Aarstad O., Svanem B. I., Valla S. (2009) Characterization of three new Azotobacter vinelandii alginate lyases, one of which is involved in cyst germination. J. Bacteriol. 191, 4845–4853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Heyraud A., Gey C., Leonard C., Rochas C., Girond S., Kloareg B. (1996) NMR spectroscopy analysis of oligoguluronates and oligomannuronates prepared by acid or enzymatic hydrolysis of homopolymeric blocks of alginic acid. Application to the determination of the substrate specificity of Haliotis tuberculata alginate lyase. Carbohydr. Res. 289, 11–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang Z., Yu G., Guan H., Zhao X., Du Y., Jiang X. (2004) Preparation and structure elucidation of alginate oligosaccharides degraded by alginate lyase from Vibro sp. 510. Carbohydr. Res. 339, 1475–1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ogura K., Yamasaki M., Mikami B., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2008) Substrate recognition by family 7 alginate lyase from Sphingomonas sp. A1. J. Mol. Biol. 380, 373–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Preiss J., Ashwell G. (1963) Polygalacturonic acid metabolism in bacteria. I. Enzymatic formation of 4-deoxy-l-threo-5-hexoseulose uronic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 238, 1571–1583 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hashimoto W., Miyake O., Momma K., Kawai S., Murata K. (2000) Molecular identification of oligoalginate lyase of Sphingomonas sp. strain A1 as one of the enzymes required for complete depolymerization of alginate. J. Bacteriol. 182, 4572–4577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ochiai A., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2006) A biosystem for alginate metabolism in Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58: molecular identification of Atu3025 as an exotype family PL-15 alginate lyase. Res. Microbiol. 157, 642–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kuorelahti S., Jouhten P., Maaheimo H., Penttilä M., Richard P. (2006) l-Galactonate dehydratase is part of the fungal path for d-galacturonic acid catabolism. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 1060–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Preiss J., Ashwell G. (1962) Alginic acid metabolism in bacteria. II. The enzymatic reduction of 4-deoxy-l-erythro-5-hexoseulose uronic acid to 2-keto-3-deoxy-d-gluconic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 237, 317–321 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Momma K., Okamoto M., Mishima Y., Mori S., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2000) A novel bacterial ATP-binding cassette transporter system that allows uptake of macromolecules. J. Bacteriol. 182, 3998–4004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hashimoto W., Kawai S., Murata K. (2010) Bacterial supersystem for alginate import/metabolism and its environmental and bioenergy applications. Bioeng. Bugs 1, 97–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wargacki A. J., Leonard E., Win M. N., Regitsky D. D., Santos C. N., Kim P. B., Cooper S. R., Raisner R. M., Herman A., Sivitz A. B., Lakshmanaswamy A., Kashiyama Y., Baker D., Yoshikuni Y. (2012) An engineered microbial platform for direct biofuel production from brown macroalgae. Science 335, 308–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ogura K., Yamasaki M., Yamada T., Mikami B., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2009) Crystal structure of family 14 polysaccharide lyase with pH-dependent modes of action. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 35572–35579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yoon H. J., Hashimoto W., Miyake O., Murata K., Mikami B. (2001) Crystal structure of alginate lyase A1-III complexed with trisaccharide product at 2.0 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 307, 9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ochiai A., Yamasaki M., Mikami B., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2010) Crystal structure of exotype alginate lyase Atu3025 from Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24519–24528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]