Background: PAR1 has been shown to regulate the response to vascular injury, however, the respective roles of its activating proteases, thrombin and MMP-1, are unknown.

Results: MMP-1-PAR1 signaling triggers SMC dedifferentiation and arterial stenosis, whereas thrombin-PAR1 promotes a contractile phenotype.

Conclusion: PAR1 exhibits biased agonism to the two activating proteases, MMP-1 versus thrombin.

Significance: Inhibition of MMP-1-PAR1 may provide benefits in suppressing arterial stenosis.

Keywords: Cardiovascular Disease, Cell Differentiation, Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP), Smooth Muscle, Thrombin, PAR1

Abstract

Vascular injury that results in proliferation and dedifferentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) is an important contributor to restenosis following percutaneous coronary interventions or plaque rupture. Protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR1) has been shown to play a role in vascular repair processes; however, little is known regarding its function or the relative roles of the upstream proteases thrombin and matrix metalloprotease-1 (MMP-1) in triggering PAR1-mediated arterial restenosis. The goal of this study was to determine whether noncanonical MMP-1 signaling through PAR1 would contribute to aberrant vascular repair processes in models of arterial injury. A mouse carotid arterial wire injury model was used for studies of neointima hyperplasia and arterial stenosis. The mice were treated post-injury for 21 days with a small molecule inhibitor of MMP-1 or a direct thrombin inhibitor and compared with vehicle control. Intimal and medial hyperplasia was significantly inhibited by 2.8-fold after daily treatment with the small molecule MMP-1 inhibitor, an effect that was lost in PAR1-deficient mice. Conversely, chronic inhibition of thrombin showed no benefit in suppressing the development of arterial stenosis. Thrombin-PAR1 signaling resulted in a supercontractile, differentiated phenotype in SMCs. Noncanonical MMP-1-PAR1 signaling resulted in the opposite effect and led to a dedifferentiated phenotype via a different G protein pathway. MMP-1-PAR1 significantly stimulated hyperplasia and migration of SMCs, and resulted in down-regulation of SMC contractile genes. These studies provide a new mechanism for the development of vascular intimal hyperplasia and suggest a novel therapeutic strategy to suppress restenosis by targeting noncanonical MMP-1-PAR1 signaling in vascular SMCs.

Introduction

Atherothrombotic disease remains the leading cause of death in the United States and Western nations (1). Despite successful percutaneous coronary interventions, 20% of patients still experience a recurrent major adverse cardiac event within 3 years of treatment (2). Furthermore, more than 60% of adverse events and nearly half of all deaths are a consequence of the initial culprit lesion, suggesting that destructive vascular remodeling continues even in the face of lesion ablation and widespread use of drug-eluting stents (2).

Aberrant repair processes following atherosclerotic plaque rupture or iatrogenic intervention are mediated by vascular SMCs (3–5).2 SMC proliferation, migration, and reversion of from a differentiated contractile phenotype to a dedifferentiated “synthetic” phenotype are crucial contributors to the pathology associated with maladaptive remodeling in culprit lesions (3, 4). SMC dedifferentiation results in morphological changes in the vessel wall that are initially adaptive but later can become injurious and lead to restenosis and recurrence of ischemic symptoms. Despite the recognition that SMCs have plastic differentiation capacity, the signaling cascades triggering phenotypic switching in the blood vessel wall remain poorly understood.

We recently showed that protease activated receptor-1 (PAR1), the major thrombin receptor on human platelets (6), regulates arterial stenosis (7); however, it is not known whether PAR1 on SMCs promotes or mitigates the hyperplastic response to arterial injury in the chronic setting (8). Thus, genetic deletion of PAR1 gave no net positive benefit in preventing medial thickening (9) but paradoxically resulted in increased intimal growth in mouse models of arterial injury (7). Likewise, studies with thrombin inhibitors have not demonstrated a beneficial effect in preventing restenosis of culprit lesions after percutaneous coronary intervention (2, 10, 11). Because PAR1 is activated by other proteolytic cascades besides thrombin, in particular the major interstitial collagenase MMP-1 (12), we hypothesized that differential proteolytic cascades may play opposing roles in regulating SMC behavior following vascular injury.

MMPs such as MMP-1 comprise a family of zinc-dependent proteases whose major function is the breakdown of extracellular matrix polymers (13). MMPs have also proven to be critical regulators of vessel wall homeostasis and inflammation through cleavage of soluble bioactive molecules (14). SMCs constitutively express certain MMPs that are up-regulated in diseased arteries (15–18). Clinical studies have shown significant increases in circulating MMPs in patients following vascular injury and rupture of atherosclerotic plaques (19, 20). In particular, MMP-1 has emerged as an important contributor to vascular remodeling, and atherothrombosis (15, 17, 19, 21). However, little is known regarding the effect of direct MMP-1 stimulation on SMC function. Here, we sought to determine whether chronic inhibition of the upstream activating proteases, MMP-1 versus thrombin, would have differing effects on the stenotic process following arterial injury. We made the unexpected discovery that noncanonical activation of PAR1 by MMP-1 led to dedifferentiation and hyperplasia of SMCs. Thrombin-PAR1 signaling resulted in a supercontractile, differentiated phenotype. Upstream inhibition of MMP-1 may provide the advantage of selectively antagonizing a noncanonical PAR1 signaling cascade that promotes restenosis without adversely affecting thrombin-PAR1 hemostasis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Carotid Artery Wire Injury

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines of the U.S. National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the Tufts Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male WT or PAR1-deficient C57BL/6 (14–16 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories or bred at Tufts Medical Center (7). The left common carotid arteries were denuded with a vascular wire as previously described (22). Briefly, the mice were anesthetized with aerosolized isoflurane gas, and a midline neck incision was made exposing the common carotid. A flexible wire was inserted caudally into the common carotid from the external carotid. The wire was threaded back and forth 10 times along the exposed length of the common carotid. Buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) was provided as a post-operative analgesic. The mice were treated daily with 100 μl of subcutaneous injections of 5 mg/kg FN-439 (Calbiochem), 10 mg/kg bivalirudin (Medicines Company), or 20% Me2SO vehicle starting the day of injury. The mice were sacrificed 21 days post-injury, and the arteries were harvested for sectioning and histological analysis. Contra-lateral carotids were used as uninjured controls.

Carotid Artery Morphometry and Immunofluorescence

Four sequential sections were taken from each paraffin-embedded artery just caudal to the bifurcation of the common carotid and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Sections taken for immunofluorescence were first deparaffinized and hydrated as follows: 100% xylene (twice for 10 min), 100% ethanol (3 min), 95% ethanol (3 min), 75% ethanol (3 min), 50% ethanol (3 min), with a rinse with PBS. Antigen retrieval was performed in 10 mm sodium citrate (pH 6) by microwaving on low for 5 min, repeated three times. The slides were subsequently blocked in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 15 min at room temperature, followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature with 2% BSA, 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS. The slides were washed with 2% BSA/PBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody (mPAR1 = SFFLRN-Ab, a rabbit polyclonal Ab raised against the mPAR1 ligand region SFFLRNPSENTFELV, 1:200; rabbit polyclonal Ab Mmp-1a, 1:200 (27); SMA-Cy3, 1:400) or IgG control (1:200). The slides were washed three times with Tris-buffered saline with 1% Tween (TBST) for 5 min. The slides were then incubated with a FITC-conjugated or IgG-Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (1:400) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by washing with TBST. The samples were then stained with DAPI (1:5000) and visualized. Hematoxylin and eosin micrographs were taken using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope and a Spot 7.4 Slider camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc.) at a magnification of 10–40×. The images were analyzed for intimal and medial thickness by measuring the length from the medial edge to the luminal surface in four quadrants of each section normalized to a known micron scale bar. The lengths were converted to microns using a known standard.

DQ-Collagen/Gelatin and S-2238 Cleavage Assays

Collagenase activity was measured using DQ-collagen or DQ-gelatin (Molecular Probes) as previously described (12). Briefly, 5 nm activated MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-8, MMP-9, and MMP-13 (Calbiochem) were diluted in 1× reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2, 0.2 mm sodium azide, pH 7.6) and used to cleave 20 μg of DQ-collagen/gelatin for 30 min at room temperature in triplicate in a 96-well plate. FN-439 (5 μm) and 1,10-phenanthroline (100 μm) were diluted in 1× reaction buffer and directly added to the wells. Fluorescence was measured at an absorption of 495 nm and emission of 515 nm on a Promega GloMax Multi Microplate Multimode reader. Thrombin protease activity was monitored by S-2238 cleavage (Chromogenix) as previously described (24). Thrombin (0.01–10 nm) was diluted in Tris buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 175 mm NaCl, 0.5 mg/ml BSA, pH 7.9) with or without bivlairudin (0.5–50 μm) to a final volume of 180 μl. 20 μl of S-2238 (2 mm) was added to each well, and the reaction was allowed to proceed at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm on a SpectraMax 340 (Molecular Devices).

Cell Culture

AO391 (derived from human aorta) and CD314 (derived from human carotid artery) cell lines were a generous gift from Wendy Bauer (Tufts Molecular Cardiology Research Institute) and were grown in DMEM (CellGro) supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Primary human coronary artery (HCA) smooth muscle cells were purchased from Invitrogen and grown in Medium-231 (Invitrogen) and smooth muscle growth supplement (Invitrogen). All experiments with HCA cells were performed between passages 2 and 5.

Immunostaining and Immunohistochemistry

SMCs were plated on 18-mm glass coverslips and serum-starved in 0.1% FBS/DMEM for 16 h and treated with 5 nm thrombin (Hematologic Technologies Inc.), 5 nm MMP-1 (Calbiochem) for 15 min. MMP-1 was activated from the proMMP-1 as follows: 500 ng of MMP-1 incubated for 7–10 min with 10 μg/ml trypsin (Calbiochem) and then trypsin-quenched with 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma) and 100 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor (Sigma). Cells treated with RWJ-56110 (5 μm) were pretreated for 15 min prior to protease exposure. Coverslips were then fixed with 4% PBS-buffered paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-300, and blocked in 0.1% Nonidet P-40/PBS. Phospho-myosin light chain 2-Ab (1:200; Cell Signaling), phospho-FAK397 (1:400; Cell Signaling), and FITC-conjugated phalloidin (1:400; Sigma) were incubated with coverslips for 1 h. A FITC-conjugated secondary (1:400; Jackson Immunolabs) was used for p-MLC and p-FAK. DAPI (Sigma) was used as a nuclear stain. For immunohistochemistry, unidentified banked patient samples were acquired from Tufts Medical Center with institutional review board approval. The slides were processed as above for immunofluorescence but stained with antibodies against hPAR1 (1:200; SFLLR-Ab), mPAR1 (1:200; mPAR1-Ab), MMP-1 (1:200; SB12e) (Santa Cruz), or smooth muscle actin (1:200; Dako). Biotinylated secondary antibody (1:400; Vector Labs) was added, followed by streptavidin-conjugated HRP (1:400; Vector Labs). Chemical reaction was initiated with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine reagent. (Pierce). Sections were then counterstained with Meyer's hematoxylin (Sigma).

Proliferation and Migration Assays

For proliferation, 2.5 × 103 cells were plated in 96-well plates in DMEM alone and serum-starved for 36 h, then treated with thrombin (5 nm), MMP-1 (5 nm), 10% FBS (Invitrogen), and/or RWJ-56110 (5 μm), and incubated at 37 °C for 3 days. The cells were washed and fixed/stained for 10 min with 0.05% (w/v) crystal violet (Sigma) in 10% ethanol. The plates were washed with distilled water and allowed to dry. Residual crystal violet was resuspended in 100% methanol (Sigma) and absorbance read at 595 nm. For BrdU incorporation experiments, 50 μm BrdU (Sigma) was added to 200,000 cells 24 h after adding proteases/inhibitors and allowed to incorporate for 2 h. Permeabilized cells were stained with 1:10 anti-BrdU monoclonal Ab (G3G4, DSHB-Univ Iowa)/FITC-conjugated secondary (1:10; Invitrogen), and the ratio of BrdU-positive cells/negative cells was assessed by FACS. For migration, 25 × 103 cells were plated in the top chamber of a 24-well Boyden chamber (Fisher) in 0.1% FBS/DMEM. Inhibitors (5 μm RWJ-56110 or 200 ng/ml pertussis toxin) were added directly to cells in the top chamber, chemoattractant was added to 0.1% FBS/DMEM in bottom chamber. The cells were allowed to migrate 16 h before membranes were stained (Wright stain), and nine fields (16×) were counted.

Wound Healing Assays

CD314 cells were grown to confluency in 6-well plates and then scratched in a cross-wise pattern four times/well with a P1000 pipette tip. Photos were taken at time 0, at which point treatment was added to each well (5 nm thrombin or MMP-1 ± 5 μm RWJ-56110). Cells were allowed to reconstitute the scratched region for 16 h, at which point additional photographs were taken. The mean number of cells migrated was quantified (n = 4 fields at 4×) and expressed as the mean ± S.E.

Immunoblots and RhoA Activation

For FAK Western blots, cells were serum-starved for 24 h in DMEM alone and then treated with 5 nm thrombin or MMP-1 for the times indicated. Nitrocellulose membranes were probed with anti-phospho-FAK (Tyr-397) antibody (1:1000; Cell Signaling) for 1 h at room temperature. Both total FAK (1:1000; Cell Signaling) and tubulin (1:5000; Sigma) antibodies were used as loading controls. For phospho-ERK Western blots, the cells were grown to confluency and serum-starved in DMEM alone for 36 h prior to treatment with thrombin (5 nm) or MMP-1 (5 nm) with or without inhibitors for 15 min at room temperature. Nitrocellulose membranes were probed for phospho-ERK (1:1000; Cell Signaling), total ERK (1:1000; Cell Signaling), and tubulin (1:5000; Sigma) For RhoA activation, confluent CD314 cells were treated with thrombin (5 nm) or MMP-1 (5 nm) with or without RWJ-56110 (5 μm) for 15 min. The cells were lysed, and Rho-GTP was precipitated from cell lysates with GST-rhotekin-reduced glutathione-agarose beads as described (23). Rho-GTP was then quantified by immunoblot analysis with monoclonal antibody to RhoA (1:400; 26C4; Santa Cruz). A portion of the SMC lysates was reserved and analyzed by immunoblot for total Rho and rhotekin as loading controls.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from SMCs using the RNeasy mini kit and treated with on-column DNase digestion (Qiagen). RNA was reverse transcribed, and real time quantitative PCR was conducted using a SYBR Green master mix (Qiagen) and a 40-cycle thermocycling protocol. The data are presented as relative fold changes in mRNA normalized to GAPDH. The following primers were used: myocardin forward primer, TGCACAGAACTCAGGAGCACACG; myocardin reverse primer, TGGGCTCCAGAGAAGGGCGG; SM-22 forward primer, CCAAGGAGCTTTCCCCAGACATGG; SM-22 reverse primer, TTGGACTGCACTTCGCGGCT; calponin forward primer, GGCCAGCATGGCGAAGACGAA; calponin reverse primer, CCCGGCTCGAATTTCCGCTCC; fibronectin forward primer, TCATCCCAGAGGTGCCCCAACTC; and fibronectin reverse, GTCCACCTCAGGCCGATGCTTG.

Endocytosis

SMCs were treated with thrombin (5 nm) or MMP-1 (5 nm) at 37 °C or 4 °C, and the cells were fixed at various time points with 1% formaldehyde and stained for PAR1 (SFLLR-Ab). FITC-conjugated secondary antibody was then added, and PAR1 surface expression was analyzed with a FACS Canto II (Becton-Dickinson). Mean fluorescence intensities were measured using FlowJo software and normalized to untreated samples to obtain a percentage of PAR1 surface expression.

Statistical Analysis

All of the values are expressed as means ± S.E. All comparisons between experimental and controls with three or more groups were performed by one-way ANOVA with the Student-Newman-Keul's post-test using Kaleidograph software. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. Student's t test was used to compare two groups.

RESULTS

MMP-1 Inhibition Reduces Medial and Intimal Lesion Area in Restenosis Models

To delineate the respective contributions of thrombin and MMP-1 to neointimal hyperplasia, wild-type mouse carotid arteries were injured (n = 14/group) with a vascular wire (22), and animals were treated daily for 21 days with either FN-439, a small molecule inhibitor that is selective for MMP-1 (12), or bivalirudin, a potent direct thrombin inhibitor that completely prevents thrombin-PAR1 cleavage (24, 25). FN-439 inhibited >94% of MMP-1 collagenase activity; 0–7% of MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-8; 21% of MMP-9; and 36% of MMP-13 activity and had no inhibitory effects against thrombin (Table 1 and supplemental Fig. S1A). At the day 21 end point, vehicle-treated animals had 4-fold increases in mean medial and intimal thickness and marked neointima formation following wire injury as compared with contralateral uninjured carotids (Fig. 1, A and B, and supplemental Table S1). Daily treatment with the MMP-1 inhibitor FN-439, gave a significant 2.4-fold (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA) protective effect against neointimal hyperplasia, whereas treatment with the thrombin inhibitor bivalirudin had no discernable effect as compared with untreated wild-type animals (Fig. 1, A and B). FN-439 lost its protective effect in mice deficient in PAR1 (PAR1 KO) and had no effect on medial and intimal thickness relative to vehicle treatment (supplemental Fig. S1B). These results indicate that unlike direct thrombin inhibition, blockade of MMP-1 activity significantly decreases arterial neointima formation and stenosis following wire injury in mice in a PAR1-dependent manner. Furthermore, these data imply that MMP-1 versus thrombin may play different roles in regulating vascular SMC hyperplasia. Because MMP-1 cleaves PAR1 at a site two amino acid residues from the thrombin cleavage site, creating a unique tethered ligand that is two residues longer than the canonical thrombin-generated ligand (Fig. 1C), we decided to test the notion that the observed divergent pathological outcomes could be dependent on the specific PAR1-activating protease.

TABLE 1.

Specificity profile of the small molecule MMP-1 inhibitor, FN-439, for various matrix metalloproteases

A panel of MMPs were tested for inhibition (mean ± S.E.; n = 3) of cleavage of Type I collagen by 5 μm FN-439 (5× IC50 for MMP-1) by hydrolysis of FITC-DQ-collagen over 30 min at 25 °C (12), using 5 nm of each enzyme including the three collagenases (MMP-1, MMP-8, and MMP-13), stromelysin (MMP-3), and matrilysin (MMP-7), or by hydrolysis of FITC-DQ-gelatin over 30 min for the two gelatinases, MMP-2 and MMP-9. 100% inhibition was defined by residual collagenase activity in the presence of 100 μm of the zinc chelator, 1,10-phenanthroline; 0% inhibition was defined as collagenase activity in reaction buffer alone.

| Enzyme | Inhibition by FN-439 |

|---|---|

| % | |

| MMP-1 | 94 ± 30 |

| MMP-2 | 0 ± 9 |

| MMP-3 | 4 ± 6 |

| MMP-7 | 1 ± 6 |

| MMP-8 | 7 ± 12 |

| MMP-9 | 21 ± 2 |

| MMP-13 | 36 ± 6 |

FIGURE 1.

MMP-1 inhibition reduces medial and intimal lesion thickness following carotid artery wire-injury in mice. A, representative photomicrographs (16×) of carotid arteries from the right uninjured contralateral artery or the left injured artery from male C57BL6 mice treated with daily subcutaneous injections of vehicle (20% Me2SO), 5 mg/kg FN-439, or 10 mg/kg bivalirudin (Bival) for 21 days (n = 14). B, medial plus intimal thickness based on a micromillimeter scale bar of injured carotid arteries harvested from mice in A. Each data point represents four averaged (quadrants) measurements from each mouse artery. Horizontal lines indicate mean medial plus intimal thickness in microns. The mean medial thickness (horizontal lines) for each treatment cohort was calculated from cross-sections of the arteries as described under “Experimental Procedures.” *, p < 0.05 by ANOVA. C, proposed mechanism of divergent signaling and outcomes resulting from PAR1 activation by MMP-1 versus thrombin at two different cleavage sites in arterial injury and restenosis. D, merged immunofluorescence of representative sections from wire-injured carotid arteries of vehicle-treated mice from A stained with Abs for smooth muscle actin (SMA-Cy3; monoclonal), mPAR1 (polyclonal), FITC-2°, or Mmp-1a (polyclonal), FITC-2°. The cell nuclei were counterstained (blue) with DAPI. The insets in the lower left corners represent magnified regions prominent co-localization in the neointima. Autofluorescence of the elastic lamina can be seen as distinct green bands.

MMP-1 Cleaves and Activates PAR1 on Smooth Muscle Cells

Like PAR1 (7, 23, 26), MMP-1 is expressed by numerous cell types in the blood vessel wall including endothelium, SMC, and macrophages (17, 18, 23, 27–29). We confirmed that both mPar1 and the mouse homolog of MMP-1, Mmp-1a (23, 27–29), were expressed in SMA-staining cells of the neointima in wire-injured carotid arteries of mice (Fig. 1D and supplemental Fig. S1D). Similarly, human MMP-1 was prominently co-localized with PAR1 in the SMCs of the neointima, media, and fibrous caps of human atherosclerotic lesions (Fig. 2, A and B). To investigate whether PAR1 is a possible target for MMP-1 on the cell surface of SMCs, we interrogated PAR1 surface expression in primary HCA and cultured AO391 and CD314 human SMCs. In all three cases, PAR1 was robustly expressed on the cell surface (2–8-fold increase above control; Fig. 2C). We then demonstrated that MMP-1 could cleave and activate PAR1 on SMCs using the Span12 antibody, which only binds uncleaved PAR1 (24). Incubation of CD314 cells with 5 nm MMP-1 resulted in a 50% loss of PAR1 Span12 epitope that was completely blocked by the MMP-1 inhibitor, FN-439 (Fig. 2D). To test whether MMP-1 could directly activate PAR1, we conducted Ca2+ flux measurements with immortalized and primary human SMCs. Treatment with 5 nm MMP-1 triggered intracellular calcium release to the same extent as equimolar thrombin, which was completely blocked by the PAR1 selective antagonist, RWJ-56110 (Fig. 2E). Like the MMP-1 inhibitor FN-439, RWJ-56110 had no effect on SMC viability (supplemental Fig. S1C). Together these data confirm that MMP-1 cleaves and activates PAR1 on SMCs.

FIGURE 2.

MMP-1 cleaves and activates PAR1 on human SMCs. A, immunohistochemistry of sections from human atherosclerotic lesions showing co-localization of SMA (1A4) with MMP-1 (SB12e) and PAR1 (SFLLR-Ab). A, adventitia; M, media; L, lumen. B, IHC of MMP-1, PAR1, and SMA depicting co-localization in the media, neointima, and endothelium of a human atherosclerotic plaque. Arrowheads point to areas of localization in the neointima. The triangles show staining in the endothelium. C, PAR1 surface expression (shaded fill) of three SMC lines analyzed by FACS using the SFLLR-Ab. 2° antibody control is shown as a black line with white fill. D, MMP-1 cleavage of PAR1 on CD314 SMCs after 30 min of treatment with 5 nm MMP-1 ± 5 μm FN-439. The Span12 antibody spanning the PAR1 cleavage site was used to recognize full-length receptor. Loss of antibody binding indicates receptor cleavage by MMP-1 (5 nm); 5 μm FN-439 MMP-1 inhibitor. E, calcium flux measurements of SMCs following challenge with MMP-1 or thrombin (5 nm thrombin or MMP-1). In the bottom traces, the cells were pretreated for 3 min with the PAR1 inhibitor 5 μm RWJ-56110 (RWJ) prior to the addition of agonist.

Because the MMP-1 inhibitor could also affect the release of bone marrow-derived stem/progenitor vascular cells into the circulation, which may modulate intimal growth, we examined the effect of FN-439 on circulating CD34+/Sca+ (stem cell antigen-1) cells following wire injury of the carotid arteries. Wire injury gave a 1.9-fold increase in circulating CD34+/Sca+ cells at day 3 after injury relative to uninjured controls (supplemental Table S2). Daily treatment with FN-439 caused a nonsignificant reduction in circulating CD34+/Sca+ cells (1.4-fold above control), whereas daily treatment with the thrombin inhibitor, bivalirudin, caused a slight nonsignificant increase (2.1-fold above control).

MMP-1 Is a Potent Chemoattractant for PAR1-dependent SMC Migration

The ability of SMCs to migrate and invade through the medial and neointimal layers toward the injured luminal surface are critical contributors to the pathology associated with neointimal hyperplasia and restenosis (4). Therefore, we compared the ability of MMP-1 versus thrombin to stimulate SMC migration. Chemotactic gradients of thrombin only slightly increased migration by 30% for AO391 and CD314 cell lines (Fig. 3A), which was completely inhibited by the PAR1 antagonist, RWJ-56110. By comparison, 5 nm MMP-1 acted as a powerful chemoattractant and gave a significant 2–2.5-fold increase in migratory response, similar to that of 10% FBS (Fig. 3A). Blockade of PAR1 with RWJ-56110 abrogated the migratory effects toward MMP-1 (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, in an alternative scratch assay of SMC migration, MMP-1 treatment significantly increased SMC migration into the wound space relative to untreated and thrombin-treated cells (Fig. 3B). The MMP-1 wound healing stimulatory activity was blocked by the PAR1 inhibitor RWJ-56110. Similar to the Boyden chamber results, thrombin gave a slight, nonsignificant increase in SMC wound healing activity.

FIGURE 3.

MMP-1 is a potent chemoattractant for PAR1-dependent SMC migration. A, 16 h of migration in Boyden chambers of AO391 and CD314 SMCs toward either 5 nm thrombin (Thr) or 5 nm MMP-1, with and without 5 μm RWJ-56110 (RWJ). B, CD314 cells were grown to confluency in 6-well plates and scratched using a sterile P1000 polypropylene pipette tip. The cells were then treated with either 5 nm thrombin or MMP-1 with or without 5 μm RWJ-56110 and allowed to migrate for 16 h. Four micrographs (4×) at times 0 and 16 h were used to compare treated and untreated (PBS buffer (vehicle)) wells. The mean numbers of cells migrated in (n = 4 fields) are quantified on the right. The data are shown as means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05 (Student's unpaired t test). C, 16 h migration of AO391, CD314, and HCA SMCs toward agonist peptides (Thr: TFLLRN, SFLLRN; MMP-1: PR-SFLLRN; Reversed MMP-1: RP-SFLLRN) at the concentrations indicated (30 and 300 μm). D, PAR1 surface expression on CD314 SMCs over 60 min as observed by FACS using the SFLLR-Ab following treatment with either 5 nm thrombin or 5 nm MMP-1. The experiments were either performed at 37 or 4 °C. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 by ANOVA.

Consistent with proteolytic activation of PAR1, the thrombin-generated PAR1 peptides SFLLRN and TFLLRN had modest effects on migration of all three PAR1-expressing SMC cell lines including primary HCA cells at 30 μm concentrations and were inhibitory or desensitizing at 10-fold higher concentration (Fig. 3C) as seen previously with other PAR1-expressing cells (30). Conversely, the MMP-1-generated noncanonical peptide ligand PR-SFLLRN, which is two residues longer than the canonical SFLLRN ligand (Fig. 1C), stimulated up to a 6-fold increase in migration in the SMC lines (Fig. 3C). A negative control MMP-1-generated peptide ligand with the first two residues reversed (31), RP-SFLLRN, had no effect on migration.

Because both thrombin and MMP-1 are capable of cutting and signaling through PAR1, albeit at sites two amino acids apart, we were surprised to observe such dramatic differences in their abilities to function as chemoattractants for vascular SMCs. Migration occurred even at high concentrations of the MMP-1 ligand (Fig. 3C), suggesting that MMP-1-PAR1 may have altered kinetics of endocytosis/recycling as a means of prolonging the protease signal (32). Both MMP-1 and thrombin stimulation (5 nm) resulted in rapid and efficient internalization (65 and 95%, respectively) of PAR1 by 5 min at 37 °C; however, activation by MMP-1 resulted in faster re-emergence of PAR1, with 100% surface expression returning by 30 min (Fig. 3D). Thrombin resulted in a return of only 40% PAR1 surface expression by 30–60 min. This is consistent with previous reports that thrombin-activated PAR1 is internalized and rapidly degraded (32). In contrast, MMP-1 activation allows accelerated appearance of PAR1. Suppression of endocytosis at 4 °C prevented loss of PAR1 surface expression by either protease agonist (Fig. 3D). The quicker reappearance of PAR1 after exposure to MMP-1 as compared with thrombin is consistent with the observation that MMP-1 is a more efficient chemoattractant for SMCs. Moreover, MMP-1 cleaved receptor may not be as efficiently targeted for destruction to the lysosome.

Thrombin-PAR1 Signaling Stimulates a Contractile Phenotype in SMCs

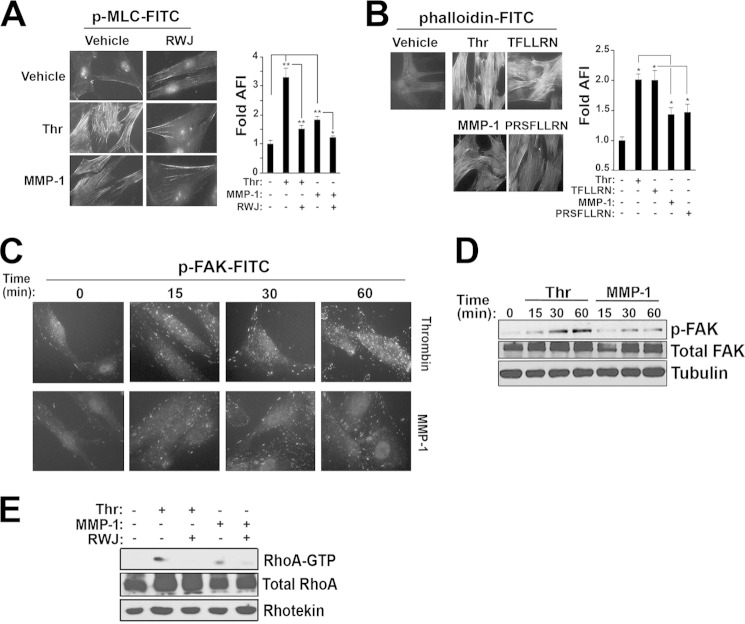

SMC contraction is important for hemostasis following large vessel injury and in regulating blood vessel hemodynamics. Furthermore, the ability to robustly contract is a major functional difference between differentiated/contractile versus dedifferentiated SMCs (4, 33). Because MMP-1 cleaves PAR1 at a unique noncanonical site from thrombin (Fig. 1C), we hypothesized that MMP-1 and thrombin differentially regulate SMC contractile function. To determine the efficacy of thrombin versus MMP-1 stimulation on SMC contractile markers, we assayed myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation and smooth muscle (F)-actin polymerization in CD314 SMCs. Thrombin-PAR1 significantly induced phosphorylation of MLC and thrombin-generated peptide agonists stimulated F-actin polymerization in the SMCs (Fig. 4, A and B) (34). MMP-1 treatment only modestly increased MLC phosphorylation, similar to the effect of the MMP-1-generated peptide on F-actin production (Fig. 4, A and B).

FIGURE 4.

Thrombin-PAR1 activates SMC contraction. A, immunofluorescence of FITC-phospho-MLC in CD314 cells treated for 15 min with either 5 nm thrombin (Thr) or 5 nm MMP-1, with and without 5 μm RWJ-56110 (RWJ). Quantification of mean green fluorescence intensity of six fields is shown on the right. DAPI was used as a nuclear counterstain. B, immunofluorescence of FITC-phalloidin in CD314 cells treated for 5 min with either 5 nm thrombin or 5 nm MMP-1, with and without 5 μm RWJ-56110. Quantification of mean green fluorescence intensity of six fields is shown on the right. DAPI was used as a nuclear counterstain. C and D, immunofluorescence of phospho-FAK-FITC (Tyr-397) following treatment with 5 nm thrombin or MMP-1 over 60 min (left). Western blot analysis of phospho-FAK (Tyr-397) following stimulation with either 5 nm thrombin or 5 nm MMP-1 at the time points indicated (right). E, Western blot analysis of RhoA bound to GTP 15 min following stimulation with either 5 nm thrombin or 5 nm MMP-1, with and without 5 μm RWJ-56110 pretreatment for 15 min.

Biochemical analysis of phosphorylation of FAK, which activates downstream proteins involved in cellular shape change and contraction (34), was also investigated as a marker of SMC contraction. FAK was phosphorylated over 60 min more robustly following stimulation with thrombin as compared with MMP-1 (Fig. 4, C and D). Because GPCR-induced cell shape change is mediated through the G12/13 family of G proteins with subsequent activation of RhoA-GTP, we tested whether thrombin and MMP-1 were capable of activating this pathway. Thrombin increased PAR1-RhoA activation to a greater extent than MMP-1; both effects were blocked by RWJ-56110 (Fig. 4E). Together, these data suggest that thrombin-PAR1 is capable of stimulating more robust contractile phenotype in SMCs as compared with MMP-1.

MMP-1-PAR1 Leads to a Dedifferentiated Phenotype in SMCs

To determine how thrombin or MMP-1 could affect the long term maintenance of a differentiated phenotype, we performed quantitative RT-PCR for several markers (33) in primary SMCs (HCA cells). Primary cells were utilized for this assay because they more closely mimic a naïve SMC state outside of the blood vessel wall. Thrombin treatment resulted in a 3–10-fold increased expression of differentiation/contractile markers of SMCs including myocardin (35, 36), SM-22 (4, 33), and calponin (4, 33), which was suppressed by the PAR1 inhibitor, RWJ-56110 (Fig. 5). Myocardin is the major transcriptional co-activator responsible for expression of the SMC gene box (35, 36) and is both necessary and sufficient for a differentiated smooth muscle phenotype. SM-22 and calponin are crucial members of the contractile apparatus and represent SMC specific gene products (4, 33). In contrast, MMP-1 treatment markedly suppressed (3–17-fold) contractile gene expression and myocardin, which was reversed by the PAR1 inhibitor (Fig. 5). Fibronectin, a component of the secreted extracellular matrix important for maintenance of a differentiated phenotype, was unaffected by thrombin but substantially decreased by MMP-1. These data indicate that activation of PAR1 by thrombin promotes a contractile/differentiated phenotype, whereas activation of PAR1 by MMP-1 triggers a dedifferentiated phenotype, which may contribute to the observed detrimental phenotypic modulation of SMCs associated with restenosis.

FIGURE 5.

MMP-1-PAR1 drives SMC dedifferentiation. Shown are the results of quantitative RT-PCR in 1° HCA cells of myocardin, SM-22, calponin, and fibronectin following 24 h of treatment with either 5 nm thrombin (Thr) or 5 nm MMP-1, with and without 5 μm RWJ-56110 (RWJ). The data are expressed as relative fold changes of triplicate samples normalized to GAPDH. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 by ANOVA.

MMP-1 and Thrombin Stimulate SMC Proliferation through PAR1

Another critical feature of dedifferentiated SMCs is their ability to re-enter the cell cycle and proliferate to repair the injured site (3, 4, 37). Overpersistence of the hyperplastic phenotype of SMCs can eventually narrow the vessel lumen resulting in a stenotic lesion. We found that both MMP-1 and thrombin stimulated PAR1-dependent proliferation (cell number) of cultured and primary SMCs to a similar extent (Fig. 6, A–C). The thrombin (TFLLRN) and MMP-1 (PR-SFLLRN)-generated peptide ligands recapitulated the proliferative effects on SMCs observed with either thrombin or MMP-1, which was blocked by the PAR1 antagonist, RWJ-56110 (Fig. 6A). Using BrdU incorporation, we confirmed that proliferative effects of thrombin and MMP-1 on primary SMCs were blocked by RWJ-56110 (supplemental Fig. S2A). Thrombin-stimulated phospho-ERK in CD314 SMCs was blocked by the PAR1 inhibitor; MMP-1 stimulation of phospho-ERK was blocked by both the MMP-1 and PAR1 inhibitors (supplemental Fig. S2B).

FIGURE 6.

Thrombin and MMP-1 differentially signal through PAR1-Gi pathways in SMC proliferation. A, fold change in proliferation (DNA crystal violet staining, A595 nm) after 3 days of treatment with 5 nm thrombin (Thr), 5 nm MMP-1, 300 μm TFLLRN, or 300 μm PR-SFLLRN, with or without 5 μm RWJ-56110 (RWJ) in AO391 cell line. B, fold change in proliferation of HCA cells after 3 days of treatment with 5 nm thrombin or 5 nm MMP-1, with and without 5 μm RWJ-56110. C, proliferative dose-response curves in CD314 cells to thrombin and MMP-1 over the concentrations (nm) indicated. D, representative calcium traces of AO391 cells treated with either 5 nm thrombin or 5 nm MMP-1. Cells were pretreated with 200 ng/ml PTx for 16 h. E, 24 h of proliferation of CD314 cells treated with either 5 nm thrombin or 5 nm MMP-1, with and without 200 ng/ml PTx. All proliferation assays are representative graphs expressing average fold changes from six individual replicates per treatment. F and G, ERK1/2 phosphorylation in AO391 (F) and CD314 (G) cells 15 min after treatment with either 5 nm thrombin or 5 nm MMP-1 in the presence of 5 μm RWJ-56110 or 200 ng/ml PTx. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 by ANOVA.

Thrombin and MMP-1 Differentially Signal through PAR1-Gi Pathways in SMCs

PAR1 exhibits promiscuous G protein coupling with three of the four Gα families: Gi, G12/13, and Gq. Following our observations that MMP-1 and thrombin produced different functional outcomes in SMCs, we first ascertained whether the Gi inhibitor pertussis toxin (PTx) could affect intracellular calcium mobilization in SMCs. Thrombin-stimulated calcium flux was completely inhibited by the addition of PTx, whereas the MMP-1 signal was only partially suppressed (Fig. 6D). Thrombin-PAR1-induced proliferation was inhibited by PTx, whereas MMP-1-PAR1-induced proliferation was not (Fig. 6E). Moreover, PTx blocked thrombin-stimulated ERK phosphorylation but instead enhanced MMP-1-ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 6, F and G). The βγ subunits coupled to PAR1-Gi are potent activators of PLC-β- and calcium-dependent pathways (38). Accordingly, inhibitors of PLC-β and calcium, U73122 and BAPTA-AM, respectively, suppressed ERK phosphorylation induced by thrombin, but conversely increased MMP-1-induced activation of phospho-ERK (supplemental Fig. S2C). These results demonstrate that thrombin-PAR1 activates mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways and proliferation through Gi, whereas MMP-1-PAR1 utilizes a non-Gi pathway in SMCs.

DISCUSSION

Matrix metalloprotease-1 has been implicated in the pro-inflammatory and tissue-remodeling events leading to cleavage of collagen in the vascular wall and promotion of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque formation (16–18). Recently, there has been an increasing awareness of the potential clinical utility of measuring circulating MMP-1 levels for risk stratification in acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing coronary intervention and stenting (39, 40). MMP-1 is also significantly elevated in patients with high intimal/medial ratios in their carotid artery plaques (41). Here, we provide evidence for a previously unknown vascular remodeling mechanism by which MMP-1-PAR1 drives arterial stenosis following injury of carotid arteries and leads to intimal hyperplasia and dedifferentiation of SMCs. Activated PAR1 exhibited metalloprotease-specific signaling patterns distinct from thrombin activation, known as biased agonism, that produced divergent functional outputs by the SMCs. Treatment of wild-type mice with the MMP-1-targeted small molecule inhibitor FN-439 led to significantly reduced neointimal formation following wire injury of carotid arteries, an effect that was lost in PAR1-deficient mice. Conversely, inhibition of thrombin showed no benefit. Thrombin-PAR1 signaling caused rapid induction of the contractile apparatus of SMCs and resulted in a supercontractile, differentiated phenotype. MMP-1-PAR1 resulted in the opposite effect and led to a dedifferentiated phenotype via a different G protein pathway.

Dedifferentiation of SMCs results in the transformation from a quiescent, contractile cell to a proliferative and migratory one, lacking an organized contractile apparatus (4). The pathologic role of phenotypic modulation of SMCs in cardiovascular disease has been well established (4), and current therapeutic strategies, including drug eluting stents, are aimed at targeting SMC dedifferentiation (42). Considering the role of MMPs in vascular matrix remodeling, especially in intimal thickening following balloon angioplasty and stenting (43, 44), MMP inhibitors have been evaluated in clinical trials for the prevention of restenosis following percutaneous coronary intervention (45). The BRILLIANT-EU study examined whether stents coated with the broad spectrum MMP inhibitor batimastat (IC50 values are 3, 4, 4, 6, and 20 nm for MMP-1, -2, -9, -7, and -3, respectively) would suppress restenosis. The study showed that batimastat-coated stents were safe in larger populations (n = 550), although there was no significant benefit at primary (major adverse cardiac events) or secondary (binary restenosis, subacute thrombosis, angiography) end points (45). Because some MMPs can provide beneficial effects, development of more selective MMP inhibitors, especially ones directed against MMP-1, could prove useful for upstream blockade of a MMP-1-PAR1 restenotic pathway following percutaneous coronary intervention.

Downstream inhibition of PAR1 has had salutary effects in animal models of restenosis (15), but orally active PAR1 inhibitors such as vorapaxar (46) can have adverse effects on hemostasis (47). Direct thrombin and Xa inhibitors have shown promise in the treatment of atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism (48), but similar to PAR1 inhibitors, there is a dose-dependent increased risk for bleeding, and they have not been thoroughly evaluated in phase III clinical trials for patients with acute coronary syndromes. Moreover, consistent with the in vivo results obtained here, clinical studies with thrombin inhibitors have not demonstrated a beneficial effect in preventing restenosis of culprit lesions after percutaneous coronary intervention (2, 10, 11). Inhibition of the upstream protease MMP-1 may provide the advantage of specifically impacting PAR1 signaling cascades that promote phenotypic switching and restenosis, without affecting thrombin-PAR1-driven hemostasis.

In addition to MMP-1, the second major vascular collagenase, MMP-13, was recently identified as having PAR1 agonist activity in cardiomyocytes leading to cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure (49). MMP-13 was found to cleave PAR1 at a slightly different site from both MMP-1 and thrombin, one residue toward the C-terminal side of the thrombin cleavage site (49). It is unclear whether MMP-13-PAR1 signaling plays a similar role to MMP-1 in SMC-mediated vascular remodeling. Although FN-439 has preferential selectivity for MMP-1, FN-439 gave partial (36%) inhibition of MMP-13. It is therefore possible that MMP-13 could be contributing to the observed in vivo inhibitory effects of FN-439 on arterial stenosis. Neutrophil collagenase MMP-8 has also been identified in unstable atherosclerotic plaques (50). However, FN-439 was unable to inhibit MMP-8 to any appreciable extent, and MMP-8 has not yet been documented to act as a functional PAR1 agonist.

In conclusion, we provide evidence for a MMP-1-PAR1 signaling axis that promotes SMC dedifferentiation, resulting in increased cell proliferation and migration, while down-regulating expression of proteins that are critical for SMC contraction. Conversely, thrombin-PAR1 signaling led to a differentiated, contractile phenotype that did not promote arterial stenosis. By targeting MMP-1 upstream and by sparing thrombin and PAR1, we suggest a new strategy to selectively impact this unique property of PAR1-biased agonism in SMC plasticity without adversely affecting normal repair processes or hemostasis.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants F30 HL108590 (to K. M. A.) and P50 HL110789 (to A. K.).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1 and S2.

- SMC

- smooth muscle cell

- PAR

- protease-activated receptor

- MMP

- matrix metalloprotease

- Ab

- antibody

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- MLC

- myosin light chain

- FAK

- focal adhesion kinase

- PTx

- pertussis toxin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Heidenreich P. A., Trogdon J. G., Khavjou O. A., Butler J., Dracup K., Ezekowitz M. D., Finkelstein E. A., Hong Y., Johnston S. C., Khera A., Lloyd-Jones D. M., Nelson S. A., Nichol G., Orenstein D., Wilson P. W., Woo Y. J. (2011) Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States. A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 123, 933–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stone G. W., Maehara A., Lansky A. J., de Bruyne B., Cristea E., Mintz G. S., Mehran R., McPherson J., Farhat N., Marso S. P., Parise H., Templin B., White R., Zhang Z., Serruys P. W. (2011) A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 226–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Doran A. C., Meller N., McNamara C. A. (2008) Role of smooth muscle cells in the initiation and early progression of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 812–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Owens G. K., Kumar M. S., Wamhoff B. R. (2004) Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol. Rev. 84, 767–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smyth S. S., Pathak A., Stouffer G. A. (2002) In-stent restenosis. More fuel for the fire. Am. Heart J. 144, 577–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang P., Gruber A., Kasuda S., Kimmelstiel C., O'Callaghan K., Cox D. H., Bohm A., Baleja J. D., Covic L., Kuliopulos A. (2012) Suppression of arterial thrombosis without affecting hemostatic parameters with a cell-penetrating PAR1 pepducin. Circulation 126, 83–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sevigny L. M., Austin K. M., Zhang P., Kasuda S., Koukos G., Sharifi S., Covic L., Kuliopulos A. (2011) Protease-activated receptor-2 modulates protease-activated receptor-1-driven neointimal hyperplasia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31, e100–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leger A. J., Covic L., Kuliopulos A. (2006) Protease-activated receptors in cardiovascular diseases. Circulation 114, 1070–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheung W. M., D'Andrea M. R., Andrade-Gordon P., Damiano B. P. (1999) Altered vascular injury responses in mice deficient in protease-activated receptor-1. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19, 3014–3024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burchenal J. E., Marks D. S., Tift Mann J., Schweiger M. J., Rothman M. T., Ganz P., Adelman B., Bittl J. A. (1998) Effect of direct thrombin inhibition with Bivalirudin (Hirulog) on restenosis after coronary angioplasty. Am. J. Cardiol. 82, 511–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Preisack M. B., Baildon R., Eschenfelder V., Foley D., Garcia E., Kaltenbach M., Meisner C., Selbmann H. K., Serruys P. W., Shiu M. F., Sujatta M., Bonan R., Karsch K. R. (1997) [Low molecular weight heparin, reviparin, after PTCA. Results of a randomized double-blind, standard heparin and placebo controlled multicenter study (REDUCE) Study]. Z. Kardiol. 86, 581–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boire A., Covic L., Agarwal A., Jacques S., Sherifi S., Kuliopulos A. (2005) PAR1 is a matrix metalloprotease-1 receptor that promotes invasion and tumorigenesis of breast cancer cells. Cell 120, 303–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Newby A. C. (2012) Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition therapy for vascular diseases. Vascul. Pharmacol. 56, 232–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Butler G. S., Overall C. M. (2009) Proteomic identification of multitasking proteins in unexpected locations complicates drug targeting. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8, 935–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Andrade-Gordon P., Derian C. K., Maryanoff B. E., Zhang H. C., Addo M. F., Cheung W., Damiano B. P., D'Andrea M. R., Darrow A. L., de Garavilla L., Eckardt A. J., Giardino E. C., Haertlein B. J., McComsey D. F. (2001) Administration of a potent antagonist of protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) attenuates vascular restenosis following balloon angioplasty in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 298, 34–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Galis Z. S., Sukhova G. K., Lark M. W., Libby P. (1994) Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases and matrix degrading activity in vulnerable regions of human atherosclerotic plaques. J. Clin. Invest. 94, 2493–2503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nikkari S. T., O'Brien K. D., Ferguson M., Hatsukami T., Welgus H. G., Alpers C. E., Clowes A. W. (1995) Interstitial collagenase (MMP-1) expression in human carotid atherosclerosis. Circulation 92, 1393–1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sukhova G. K., Schönbeck U., Rabkin E., Schoen F. J., Poole A. R., Billinghurst R. C., Libby P. (1999) Evidence for increased collagenolysis by interstitial collagenases-1 and -3 in vulnerable human atheromatous plaques. Circulation 99, 2503–2509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lehrke M., Greif M., Broedl U. C., Lebherz C., Laubender R. P., Becker A., von Ziegler F., Tittus J., Reiser M., Becker C., Göke B., Steinbeck G., Leber A. W., Parhofer K. G. (2009) MMP-1 serum levels predict coronary atherosclerosis in humans. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 8, 50–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu Y. W., Yang W. S., Chen M. F., Lee B. C., Hung C. S., Liu Y. C., Jeng J. S., Huang P. J., Kao H. L. (2008) High serum level of matrix metalloproteinase-1 and its rapid surge after intervention in patients with significant carotid atherosclerosis. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 107, 93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee R. T., Schoen F. J., Loree H. M., Lark M. W., Libby P. (1996) Circumferential stress and matrix metalloproteinase 1 in human coronary atherosclerosis. Implications for plaque rupture. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 16, 1070–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang J., Nie L., Razavian M., Ahmed M., Dobrucki L. W., Asadi A., Edwards D. S., Azure M., Sinusas A. J., Sadeghi M. M. (2008) Molecular imaging of activated matrix metalloproteinases in vascular remodeling. Circulation 118, 1953–1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tressel S. L., Kaneider N. C., Kasuda S., Foley C., Koukos G., Austin K., Agarwal A., Covic L., Opal S. M., Kuliopulos A. (2011) A matrix metalloprotease-PAR1 system regulates vascular integrity, systemic inflammation and death in sepsis. EMBO Mol. Med. 3, 370–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kimmelstiel C., Zhang P., Kapur N. K., Weintraub A., Krishnamurthy B., Castaneda V., Covic L., Kuliopulos A. (2011) Bivalirudin is a dual inhibitor of thrombin and collagen-dependent platelet activation in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 4, 171–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leger A. J., Jacques S. L., Badar J., Kaneider N. C., Derian C. K., Andrade-Gordon P., Covic L., Kuliopulos A. (2006) Blocking the protease-activated receptor 1–4 heterodimer in platelet-mediated thrombosis. Circulation 113, 1244–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nelken N. A., Soifer S. J., O'Keefe J., Vu T. K., Charo I. F., Coughlin S. R. (1992) Thrombin receptor expression in normal and atherosclerotic human arteries. J. Clin. Invest. 90, 1614–1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Foley C. J., Luo C., O'Callaghan K., Hinds P. W., Covic L., Kuliopulos A. (2012) Matrix metalloprotease-1a promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 24330–24338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pfaffen S., Hemmerle T., Weber M., Neri D. (2010) Isolation and characterization of human monoclonal antibodies specific to MMP-1A, MMP-2 and MMP-3. Exp. Cell Res. 316, 836–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pfaffen S., Frey K., Stutz I., Roesli C., Neri D. (2010) Tumour-targeting properties of antibodies specific to MMP-1A, MMP-2 and MMP-3. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 37, 1559–1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kamath L., Meydani A., Foss F., Kuliopulos A. (2001) Signaling from protease-activated receptor-1 inhibits migration and invasion of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 61, 5933–5940 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Trivedi V., Boire A., Tchernychev B., Kaneider N. C., Leger A. J., O'Callaghan K., Covic L., Kuliopulos A. (2009) Platelet matrix metalloprotease-1 mediates thrombogenesis by activating PAR1 at a cryptic ligand site. Cell 137, 332–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Trejo J. (2003) Protease-activated receptors. New concepts in regulation of G protein-coupled receptor signaling and trafficking. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 307, 437–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gomez D., Owens G. K. (2012) Smooth muscle cell phenotypic switching in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 95, 156–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gerthoffer W. T. (2005) Actin cytoskeletal dynamics in smooth muscle contraction. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 83, 851–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Parmacek M. S. (2008) Myocardin. Dominant driver of the smooth muscle cell contractile phenotype. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 1416–1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Long X., Bell R. D., Gerthoffer W. T., Zlokovic B. V., Miano J. M. (2008) Myocardin is sufficient for a smooth muscle-like contractile phenotype. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 1505–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Komatsu M., Ruoslahti E. (2005) R-Ras is a global regulator of vascular regeneration that suppresses intimal hyperplasia and tumor angiogenesis. Nat. Med. 11, 1346–1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hatziapostolou M., Koukos G., Polytarchou C., Kottakis F., Serebrennikova O., Kuliopulos A., Tsichlis P. N. (2011) Tumor progression locus 2 mediates signal-induced increases in cytoplasmic calcium and cell migration. Sci. Signal. 4, ra55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eckart R. E., Uyehara C. F., Shry E. A., Furgerson J. L., Krasuski R. A. (2004) Matrix metalloproteinases in patients with myocardial infarction and percutaneous revascularization. J. Interv. Cardiol. 17, 27–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pearce E., Tregouet D. A., Samnegård A., Morgan A. R., Cox C., Hamsten A., Eriksson P., Ye S. (2005) Haplotype effect of the matrix metalloproteinase-1 gene on risk of myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 97, 1070–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gaubatz J. W., Ballantyne C. M., Wasserman B. A., He M., Chambless L. E., Boerwinkle E., Hoogeveen R. C. (2010) Association of circulating matrix metalloproteinases with carotid artery characteristics. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Carotid MRI Study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 1034–1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Navarese E. P., Kubica J., Gurbel P. A. (2011) Sirolimus or paclitaxel drug eluting stent in left main disease. The winner is …. Int. J. Cardiol. 152, 387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zempo N., Koyama N., Kenagy R. D., Lea H. J., Clowes A. W. (1996) Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation in vitro and in injured rat arteries by a synthetic matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 16, 28–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. de Smet B. J., de Kleijn D., Hanemaaijer R., Verheijen J. H., Robertus L., van Der Helm Y. J., Borst C., Post M. J. (2000) Metalloproteinase inhibition reduces constrictive arterial remodeling after balloon angioplasty. A study in the atherosclerotic Yucatan micropig. Circulation 101, 2962–2967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Peterson J. T. (2006) The importance of estimating the therapeutic index in the development of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. Cardiovasc. Res. 69, 677–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gurbel P. A., Jeong Y. H., Tantry U. S. (2011) Vorapaxar. A novel protease-activated receptor-1 inhibitor. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 20, 1445–1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tricoci P., Huang Z., Held C., Moliterno D. J., Armstrong P. W., Van de Werf F., White H. D., Aylward P. E., Wallentin L., Chen E., Lokhnygina Y., Pei J., Leonardi S., Rorick T. L., Kilian A. M., Jennings L. H., Ambrosio G., Bode C., Cequier A., Cornel J. H., Diaz R., Erkan A., Huber K., Hudson M. P., Jiang L., Jukema J. W., Lewis B. S., Lincoff A. M., Montalescot G., Nicolau J. C., Ogawa H., Pfisterer M., Prieto J. C., Ruzyllo W., Sinnaeve P. R., Storey R. F., Valgimigli M., Whellan D. J., Widimsky P., Strony J., Harrington R. A., Mahaffey K. W. (2012) Thrombin-receptor antagonist vorapaxar in acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 20–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Adam S. S., McDuffie J. R., Ortel T. L., Williams J. W., Jr. (2012) Comparative effectiveness of warfarin and new oral anticoagulants for the management of atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism. A systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 157, 796–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jaffré F., Friedman A. E., Hu Z., Mackman N., Blaxall B. C. (2012) β-Adrenergic receptor stimulation transactivates protease-activated receptor 1 via matrix metalloproteinase 13 in cardiac cells. Circulation 125, 2993–3003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Peeters W., Moll F. L., Vink A., van der Spek P. J., de Kleijn D. P., de Vries J. P., Verheijen J. H., Newby A. C., Pasterkamp G. (2011) Collagenase matrix metalloproteinase-8 expressed in atherosclerotic carotid plaques is associated with systemic cardiovascular outcome. Eur. Heart J. 32, 2314–2325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.